Abstract

The prevalence and spectrum of germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been reported in single populations, with the majority of reports focused on Caucasians in Europe and North America. The Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) has assembled data on 18,435 families with BRCA1 mutations and 11,351 families with BRCA2 mutations ascertained from 69 centers in 49 countries on 6 continents. This study comprehensively describes the characteristics of the 1,650 unique BRCA1 and 1,731 unique BRCA2 deleterious (disease-associated) mutations identified in the CIMBA database. We observed substantial variation in mutation type and frequency by geographical region and race/ethnicity. In addition to known founder mutations, mutations of relatively high frequency were identified in specific racial/ethnic or geographic groups that may reflect founder mutations and which could be used in targeted (panel) first pass genotyping for specific populations. Knowledge of the population-specific mutational spectrum in BRCA1 and BRCA2 could inform efficient strategies for genetic testing and may justify a more broad-based oncogenetic testing in some populations.

Keywords: BRCA1, BRCA2, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, mutation, ethnicity, geography

BACKGROUND

Women who carry germline mutations in either BRCA1 [OMIM 113705] or BRCA2 [600185] are at a greatly increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers. Estimates of cancer risk associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations vary depending on the population studied. For mutations in BRCA1, the estimated average risk of breast and ovarian cancers ranges from 57–65% and 20–50%, respectively (Chen and Parmigiani, 2007; Kuchenbaecker, et al., 2017). For BRCA2, average risk estimates range from 35–57% and 5–23%, respectively (Chen and Parmigiani, 2007; Kuchenbaecker, et al., 2017). Mutation-specific cancer risks have been reported that suggest breast cancer cluster regions (BCCR) and ovarian cancer cluster regions (OCCR) exist in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Kuchenbaecker, et al., 2017; Rebbeck, et al., 2015). The identification of mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 has important clinical implications, as knowledge of their presence is important for risk assessment and informs medical management for patients. Interventions, such as risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy or annual breast MRI screening, are available to women who carry deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations to enable early detection of breast cancer and for active risk reduction by risk-reducing surgery (Domchek, et al., 2010; Rebbeck, et al., 2002; Saslow, et al., 2007). The presence of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations also can influence cancer treatment decisions, principally around the use of platinum agents or poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (Lord and Ashworth, 2017) or contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy. Increasing numbers of women are having clinical genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and recommendations continue to expand to whom testing should be offered (NCCN, 2017).

In whites drawn from the general populations in North America and the United Kingdom, the prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has been estimated around a broad range from 0.1–0.3%, and 0.1–0.7%, respectively (Peto, et al., 1999; Struewing, et al., 1997; Whittemore, et al., 2004). The Australian Lifepool study, studying a control population consisting of cancer-free women ascertained via population-based mammographic screening program, estimated the overall frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to be 0.65% (1:153), with BRCA1 mutations at 0.20% (1:500) and BRCA2 mutations at 0.45% (1:222) (Thompson, et al., 2016). Estimates from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) are similar, with frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations (excluding The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data) at 0.21% (1:480) and 0.31% (1:327), respectively; or combined at 0.51% (1:195) (Maxwell, et al., 2016). As they do not include large genomic rearrangements, some newer population-based estimates may still under-represent the total number of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Although the overall prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in most general populations is low, many hundreds of thousands of yet-to-be-tested individuals worldwide carry these mutations.

The prevalence of founder mutations in some racial/ethnic groups is much higher. For example, the mutations BRCA1 c.5266dup (5382insC), BRCA1 c.68_69del (185delAG) and BRCA2 c.5946del (6174delT), have a combined prevalence of 2–3% in U.S. Ashkenazi Jews (Roa, et al., 1996; Struewing, et al., 1997; Whittemore, et al., 2004). For these mutations, double heterozygotes in BRCA1 and BRCA2 also have been reported (Friedman, et al., 1998; Moslehi, et al., 2000; Ramus, et al., 1997a; Rebbeck, et al., 2016). Several other founder mutations have been identified, including the Icelandic founder mutation BRCA2 c.771_775del (999del5) (Thorlacius, et al., 1996); the French Canadian mutations BRCA1 c.4327C>T (C4446T), and BRCA2 c.8537_8538del (8765delAG) (Oros, et al., 2006b; Tonin, et al., 1999; Tonin, et al., 2001); the BRCA1 mutations c.181T>G, and c.4034delA in Central-Eastern Europe (Gorski, et al., 2000); the BRCA1 c.548-4185del in Mexico (Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015b; Weitzel, et al., 2013)(Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015b; Weitzel, et al., 2013), the BRCA2 mutation c.9097dup in Hungary (Ramus, et al., 1997b; Van Der Looij, et al., 2000) and others. These mutations represent the majority of mutations observed in these populations and have been confirmed as true founder mutations as they have common ancestral haplotypes (Neuhausen, et al., 1996, 1998; Oros, et al., 2006a). Recurrent mutations have been identified in other populations, but they represent a smaller proportion of all unique BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and have not been characterized as true founder mutations. There are multiple recurrent mutations in Scandinavian, Dutch, French, and Italian populations (Ferla, et al., 2007). Similarly, a number of recurrent mutations specific to non-European populations also have been reported in Hispanic/Mexican, African-American, Middle Eastern, and Asian populations (Bu, et al., 2016; Ferla, et al., 2007; Kurian, 2010; Lang, et al., 2017; Ossa and Torres, 2016; Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015b).

The mutational spectra in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are best delineated in whites from Europe and North America. However, data on mutational spectra in non-white populations of Asian, African, Mediterranean, South-American and Mexican Hispanic descent have also been reported (Abugattas, et al., 2015; Ahn, et al., 2007; Alemar, et al., 2016; Bu, et al., 2016; Eachkoti, et al., 2007; Ferla, et al., 2007; Gao, et al., 2000; Gonzalez-Hormazabal, et al.; Ho, et al., 2000; Jara, et al., 2006; John, et al., 2007; Kurian, 2010; Laitman, et al.; Lang, et al., 2017; Lee, et al., 2003; Li, et al., 2006; Nanda, et al., 2005; Ossa and Torres, 2016; Pal, et al., 2004; Rodríguez, et al., 2012; Seong, et al., 2009; Sharifah, et al.; Solano, et al., 2017; Song, et al., 2005; Song, et al., 2006; Toh, et al., 2008; Torres, et al., 2007; Troudi, et al., 2007; Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015b; Vogel, et al., 2007; Weitzel, et al., 2005; Weitzel, et al., 2007; Zhang, et al., 2009). In the current study, we provide a global description of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations by geography and race/ethnicity from the investigators of the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA).

METHODS

Details of centers participating in CIMBA and data collection protocols have been reported previously (Antoniou, et al., 2007). Details of the CIMBA initiative and information about the participating centers can be found at http://cimba.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/h (Chenevix-Trench, et al., 2007). All included mutation carriers participated in clinical or research studies at the host institutions after providing informed consent under IRB-approved protocols. Sixty-nine centers and multicenter consortia submitted data that met the CIMBA inclusion criteria (Antoniou, et al., 2007). Only female carriers with pathogenic BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations were included in the current analysis. One mutation carrier per family in the CIMBA database was included in this report. The actual family relationships (e.g., pedigrees) were not available, but a variable that defined family membership supplied by each center was used for this purpose. Less than 1% of families (86 of 29,700) had two family members with two different mutations. In these situations, each mutation observed in the family was included in the analysis. In the case of the 94 dual mutation carriers (i.e., individuals with both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations), one of the two mutations was chosen at random for inclusion in the analysis.

The CIMBA data set was used to describe the distribution of mutations by effect and function. For the remaining analyses, mutations were excluded if self-reported race/ethnicity data were missing. Pathogenicity of mutation was defined as follows: 1) generating a premature termination codon (PTC), except variants generating a PTC after codon 1854 in BRCA1 and after codon 3309 of BRCA2; 2) large in-frame deletions that span one or more exons; and 3) deletion of transcription regulatory regions (promoter and/or first exon) expected to cause lack of expression of mutant allele. We also included missense variants considered pathogenic by using multifactorial likelihood approaches (Bernstein, et al., 2006; Goldgar, et al., 2004). Mutations that did not meet the above criteria but have been classified as pathogenic by Myriad Genetics, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT) also were included. Classification of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) was based on in-silico predictions and was not based on molecular classification (Anczukow, et al., 2008).

Contingency table analysis using a chi-square test was used to test for differences in dichotomous variables, as was a t-test for continuous variables. Mutation counts are presented as the number of families with the mutation. Fisher’s exact tests were used if sample sizes in any contingency table cell were less than five. Analyses were done in STATA, v. 14.2.

RESULTS

Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2

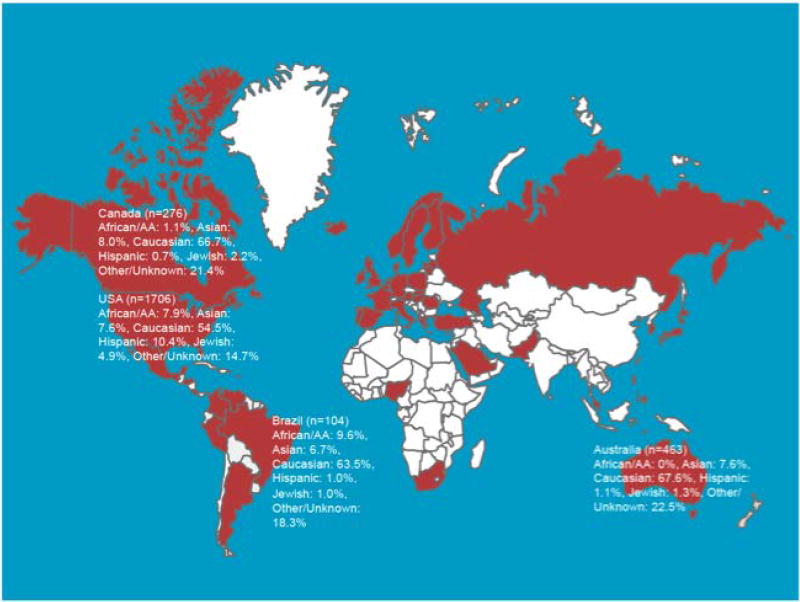

From the 26,861 BRCA1 and 16,954 BRCA2 mutation carriers in the CIMBA data set as of June 2017, 18,435 families with BRCA1 mutations and 11,351 families with BRCA2 mutations were studied to count only one occurrence of a mutation per family. Figure 1 shows the countries that contributed mutations to this report. From among these families, 1,650 unique BRCA1 and 1,731 unique BRCA2 mutations were identified. The unique mutations and number of families in which each mutation was observed are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In each gene, the five most common mutations (including founder mutations) accounted for 33% of all mutations in BRCA1 (8,739 of 26,861 mutation carriers) and 19% of all mutations in BRCA2 (3,244 of 16,954 mutation carriers). A web site containing information about the most common mutations reported here can be found at: http://apps.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/consortia/cimba/. This information may be periodically updated as new data become available.

Figure 1.

Mutation Type and Effect

Table 1 presents a summary of the type of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and their predicted effect on transcription and translation. The most common mutation type was frameshift followed by nonsense. The most common effect of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations was premature translation termination and most of the mutant mRNAs were predicted to undergo nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (Anczukow, et al., 2008). Despite having the same spectrum of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, the frequency distribution by mutation type, effect, or function differed significantly (p<0.05) between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers for many groups, as shown in Table 1. These observed differences are largely because genomic rearrangements and missense mutations account for a much higher proportion of mutations in BRCA1 when compared with BRCA2, as previously described (Welcsh and King, 2001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in the CIMBA Database (by unique mutation)

| BRCA1 | (N=1,650) | BRCA2 | (N=1,731) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Designation | Definition | N | % | N | % | ||

| Mutation Type | Large Deletion (DL) | Genomic DNA deletion (encompassing at least 1 exon) | 130 | 7.9 | 34 | 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Large Duplication (DP) | Genomic DNA duplication (encompassing at least 1 exon) | 27 | 1.6 | 11 | 0.6 | 0.010 | |

| Frameshift (FS) | Deletion or insertion resulting in a disruption of the open reading frame | 948 | 57.5 | 1,141 | 65.9 | <0.0001 | |

| In-Frame Deletion (IFD) | Small deletions, splice site mutations or large genomic rearrangements that result in a change in the mRNA but do not change the open reading frame | 1 | <0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.518 | |

| Missense (MS) | Results in an altered amino acid | 46 | 2.8 | 13 | 0.8 | 0.0001 | |

| Nonsense (NS) | Point mutation resulting in a stop codon | 313 | 19.0 | 380 | 22.0 | 0.027 | |

| Splice (SP) | Results in aberrant RNA splicing | 166 | 10.1 | 131 | 7.6 | 0.013 | |

| Multiple Types (including those listed above) | 20 | 1.1 | 19 | 1.1 | 1.00 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Mutation Effect | No RNA | Mutation is predicted to abrogate RNA production | 21 | 1.3 | 6 | 0.3 | 0.003 |

| Premature Termination Codon (PTC) | Result of a nonsense substitution, frameshift due to small deletion or insertion, aberrant splicing, or large genomic rearrangement | 1,331 | 81.0 | 1,542 | 89.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Unknown/Other | Unknown effect | 298 | 18.0 | 183 | 10.6 | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mutation Function | Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD)* (Anczukow, et al., 2008) | Mutation is predicted to result in reduced transcript level due to decay of RNA and/or degradation/instability of truncated proteins | 1,213 | 73.9 | 1,523 | 88.0 | <0.0001 |

| No NMD | Mutations generating a premature stop codon in the first or last exon that is predicted not to result in NMD | 58 | 3.5 | 16 | 0.9 | <0.0001 | |

| No RNA | Loss of expression due to deletion of promoter and/or transcription start site | 21 | 1.3 | 6 | 0.4 | 0.003 | |

| Re-Initiation | Mutations presumed to result in translation re-initiation but produce unstable protein | 4 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.294 | |

| NMD/Re-initiation | Mutations presumed to result in translation re-initiation but produce unstable protein | 60 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | -- | |

| Unknown/Other | Unknown function | 294 | 17.8 | 187 | 10.7 | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Mutation Class | 1 | Mutations predicted to be associated with unstable or no protein | 1,298 | 78.6 | 1,529 | 88.3 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | Mutations predicted to be associated with stable mutant proteins | 112 | 6.8 | 36 | 2.1 | <0.0001 | |

| 3 | Unknown function | 240 | 14.6 | 167 | 9.6 | <0.0001 | |

P-values reflect the comparison of frequencies between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

References (Anczukow, et al., 2008; Buisson, et al., 2006; Mikaelsdottir, et al., 2004; Perrin-Vidoz, et al., 2002; Ware, et al., 2006)

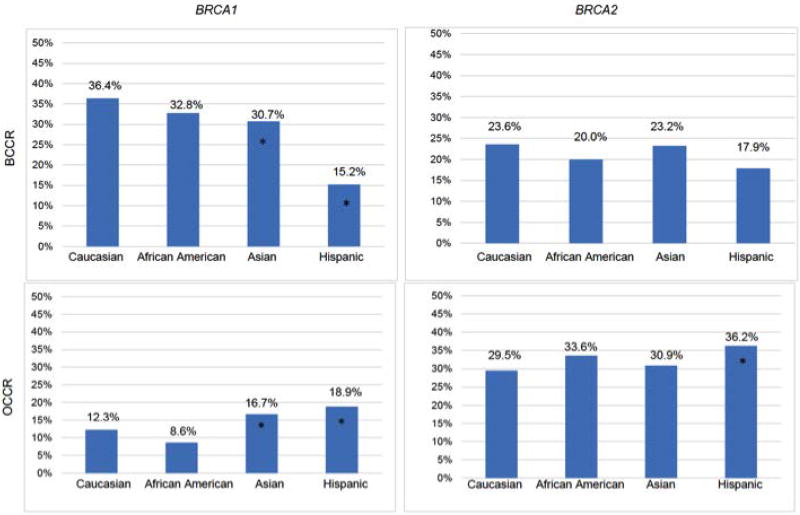

We and others have found that breast (BCCR) and ovarian (OCCR) cancer cluster regions exist that may confer differential cancer risks (Gayther, et al., 1997; Gayther, et al., 1995; Kuchenbaecker, et al., 2017; Rebbeck, et al., 2015). Figure 2 reports the relative frequency of mutations in the BCCR and OCCR by race/ethnicity. Compared with whites, we observed differences in the relative frequency of mutations in the BRCA1 BCCR and OCCR in Asians and Hispanics, and in the BRCA2 OCCR in Hispanics. To the degree that the mutations within the BCCRs and OCCRs conferred differential cancer risks, these data suggest that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation-associated cancer risks may vary by race/ethnicity.

Figure 2.

Geography and Race/Ethnicity

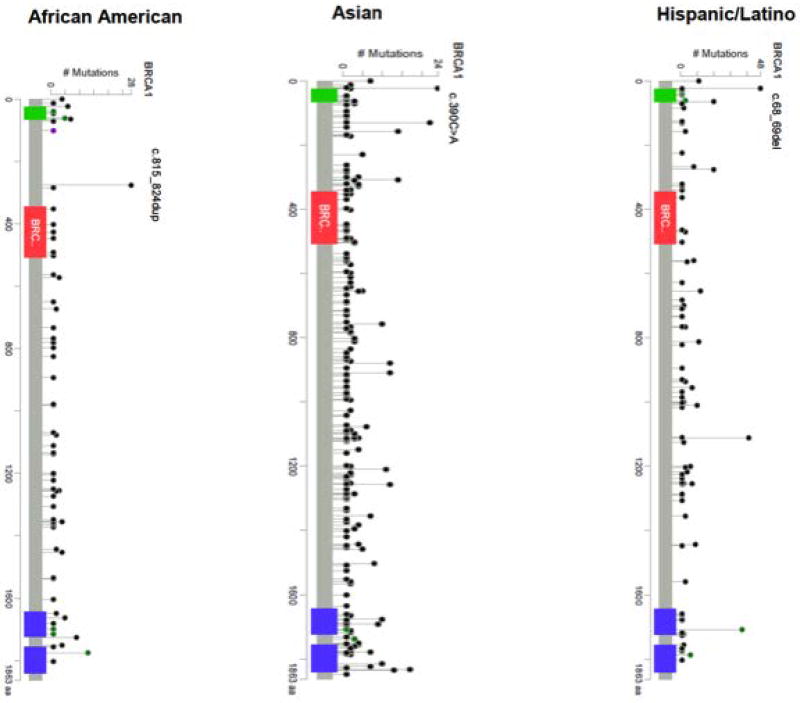

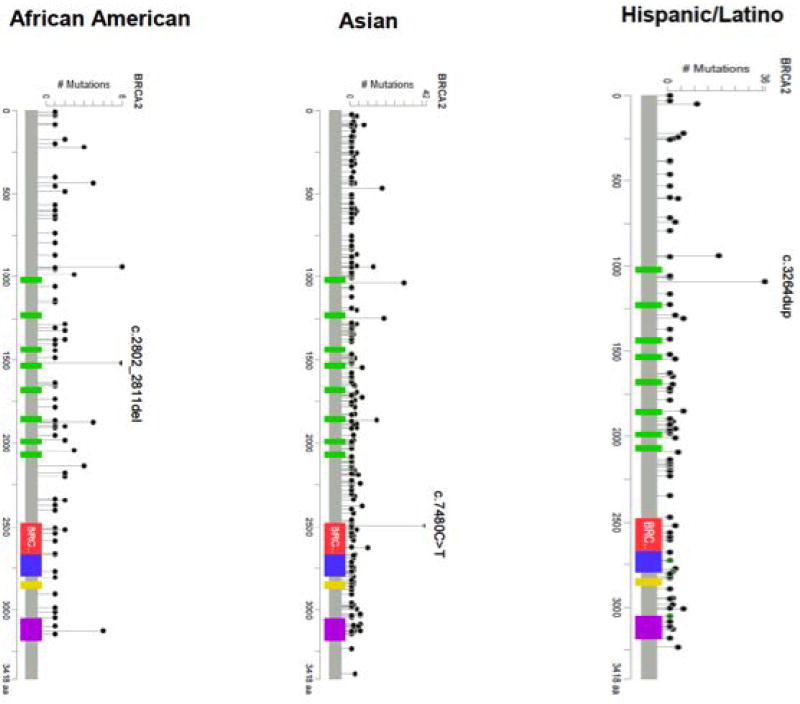

The most common mutations by country are summarized in Table 2 (BRCA1) and Table 3 (BRCA2). The locations of the mutations that were observed in African American, Asian, and Hispanic populations are depicted in Figure 3 (BRCA1) and Figure 4 (BRCA2). Some countries (Albania, Bosnia, Costa Rica, Ireland, Honduras, Japan, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Romania, Venezuela and Turkey) contributed fewer than 10 mutation carriers to the CIMBA database. Many of these mutations were submitted to the central database by CIMBA centers that ascertained these patients, but these patients originated from a different country. Based on such small numbers, it was impossible to make inferences about the relative importance of mutations in these locations. A description of the major ethnicity by country is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Common BRCA1 Mutations by Country of Origin (by family)

| Five Most Common Mutations (Number Observed) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Conti- nent |

Country | Families | Unique Mutations |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Africa | Nigeria | 20 | 15 | c.303T>G(4) | c.191G>A(2) | c.3268C>T(2) | c.4240dup(1) | c.4122_4123del(1) |

| South Africa | 49 | 16 | c.2641G>T(18) | c.5266dup(7) | c.1374del(4) | c.68_69del(4) | c.3228_3229del(4) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Asia | Hong Kong | 70 | 45 | c.470_471del(7) | c.4372C>T(5) | c.2635G>T(4) | c.5406+1_5406+3del(4) | c.3342_3345del(4) |

| Israel | 679 | 7 | c.68_69del(510) | c.5266dup(151) | c.2934T>G(13) | c.181T>G(2) | c.981_982del(1) | |

| Korea | 158 | 61 | c.390C>A(19) | c.5496_5506delinsA(17) | c.922_924delinsT(11) | c.5030_5033del(9) | c.3627dup(8) | |

| Malaysia | 72 | 47 | c.2635G>T(5) | c.68_69del (4) | c.470_471del(3) | c.4148C>G(3) | c.3770_3771del(3) | |

| Pakistan | 93 | 45 | c.5503C>T(11) | c. 3770_3771del(8) | c.4508C>A(8) | c.66dup(6) | c.2269del(1) | |

| Singapore | 28 | 18 | c.2726dup(9) | c.2617dup(2) | c.2635G>T(2) | c.213−12A>G(1) | c.3214del(1) | |

| Turkey | 1 | 1 | c.3333del(1) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Australia | Australia | 581 | 173 | c.68_69del(56) | c.5266dup(45) | c.4065_4068del (23) | c.3756_3759del (22) | c.5503C>T(16) |

|

| ||||||||

| Europe | Albania | 1 | 1 | c.4225C>T (1) | ||||

| Austria | 391 | 115 | c.181T>G(51) | c.5266dup(46) | c.3018_3021del(35) | c.1687C>T(26) | c.962G>A(17) | |

| Belgium | 166 | 41 | c.2359dup(40) | c.212+3A>G(26) | c.3661G>T(12) | c.3607C>T(10) | c.3841C>T(9) | |

| Bosnia | 1 | 1 | c.4158_4162del(1) | |||||

| Czech Rep. | 208 | 42 | c.5266dup(87) | c.3700_3704del(25) | c.181T>G(20) | c.1687C>T(16) | c.3756_3759del(6) | |

| Denmark | 667 | 101 | c.2475del(91) | c.3319G>T(81) | c.5266dup(41) | c.3710del(39) | c.c.5213G>A(30) | |

| Finland | 57 | 31 | c.3485del(8) | c. .4097−2A>G (5) | c 5266dup(4) | c.1687C>T42) | c.4327C>T(3) | |

| France | 1,522 | 418 | c.5266dup(118) | c.3481_3491del(70) | c.68_69del(63) | c.4327C>T(49) | c.3839_3843delinsAGGC (40) | |

| Germany | 2,287 | 381 | c.5266dup(411) | c.181T>G(196) | c.4689C>G(63) | c.1687C>T(62) | c.3481_3491del(55) | |

| Greece | 208 | 41 | c.5266dup(47) | c.5212G>A(29) | c.5406+644_*8273del(24) | c.5468−285_5592+4019delinsCACAG(23) | c.5251C>T(13) | |

| Hungary | 235 | 47 | c.5266dup(78) | c.181T>G(60) | c.68_69del(22) | c.5278−?_5406+?del(5) | c.5251C>T(4) | |

| Iceland | 3 | 1 | c.5074G>A(3) | |||||

| Ireland | 2 | 2 | c.547+1G>T(1) | c.427G>T(1) | ||||

| Italy | 1,120 | 254 | c.5266dup(124) | c.181T>G(44) | c.190T>C(43) | c.1687C>T(39) | c.1380dup(37) | |

| Latvia | 100 | 9 | c.5266dup(49) | c.4035del(40) | c.181T>G(5) | c.3756_3759del(1) | c.4675G>A(1) | |

| Lithuania | 223 | 21 | c.4035del(112) | c.5266dup(58) | c.181T>G221) | c.1687C>T(5) | c5177_5180del(4) | |

| Netherlands | 782 | 126 | c.5333−36_5406+400del(87) | c.5277+1G>A(66) | c.2685_2686del(60) | c.2197_2201del(41) | c.5266dup(40) | |

| Poland | 1,064 | 8 | c.5266dup(711) | c.181T>G(276) | c.4035del(69) | c.5333−36_5406+400del(3) | .68_69del(2) | |

| Portugal | 49 | 23 | c.3331_3334del(15) | c.2037delinsCC(7) | c.3817C>T(3) | c.21A>G(2) | c.5266dup(2) | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | c.5266dup(1) | |||||

| Russia | 160 | 10 | c.5266dup(135) | c.4035del(11) | c.68_69del(7) | c.5026_5027del(1) | c.4185+2T>C(1) | |

| Spain | 678 | 181 | c.211A>G(78) | c.68_69del(62) | c.5123C>A(61) | c.3770_3771del(23) | c.3331_3334del(23) | |

| Sweden | 438 | 108 | c.3048_3052dup(68) | c.1687C>T(31) | c.2475del(27) | c.1082_1092del(26) | c.5266dup(19) | |

| UK | 1,389 | 297 | c.68_69del(134) | c.4065_4068del(104) | c.4186−?_4357+?dup(78) | c.3756_3759del(62) | c.5266dup(60) | |

| North America | Canada | 450 | 112 | c.68_69del(99) | c.4327C>T(66) | c.5266dup(50) | c.2834_2836delinsC(16) | c.3756_3759del(12) |

| USA | 4,219 | 613 | c.68_69del(1130) | c.5266dup(554) | c.181T>G(113) | c.4065_4068del(58) | c.3756_3759(49) | |

|

| ||||||||

| South/Central America | Argentina | 89 | 35 | c.68_69del(22) | c.5266dup(12) | c.211A>G(11) | c.181T>G(6) | c.427G>T(3) |

| Brazil | 101 | 39 | c.5266dup(31) | c.3331_3334del(18) | c.135−?_441+?del(4) | c.1687C>T(4) | c.3916_3917del(3) | |

| Colombia | 55 | 2 | c.3331_3334del(36) | c.5123C>A(19) | ||||

| Mexico | 25 | 15 | c.548−?4185+?del(8) | c.68_69del(2) | c.824_825ins10(2) | c.211A>G(2) | c.5030_5033del(1) | |

| Peru | 1 | 1 | c.4986+6T>C(1) | |||||

| Venezuela | 1 | 1 | c.5123C>A(1) | |||||

Table 3.

Frequently Observed BRCA2 Mutations by Country of Origin (by Family)

| Five Most Frequently Observed Mutations (Number Observed) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Continent | Country | Families | Unique Mutations |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Africa | Nigeria | 12 | 9 | c.1310_1313del(3) | c.8817_8820delA(2) | c.5241_5242insTA(1) | c.2402_2412del(1) | c.994del(1) |

| South Africa | 103 | 18 | c.7934del(80) | c.5946del(6) | c.6944_6947del(2) | c.5213_5216del(1) | c.6939del(1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Asia | Hong Kong | 91 | 45 | c.3109C>T(22) | c.2808_2811del(5) | c.7878G>A(5) | c.7007G>T(4) | c.9294C>G(4) |

| Israel | 339 | 5 | c.5946del(330) | c.8537_8538del(5) | c.4936_4939del(2) | c.3847_3848del(1) | c.6024dup(1) | |

| Japan | 1 | 1 | c.5645C>A(1) | |||||

| Korea | 220 | 93 | c.7480C>T(40) | c.3744_3747del(18) | c.1399A>T(16) | c.5576_5579del(14) | c.6724_6725del(6) | |

| Malaysia | 64 | 47 | c.262_263del(8) | c.2808_2811del(3) | c.3109C>T(3) | c.5073dup(3) | c.809C>G(2) | |

| Pakistan | 19 | 17 | c.5222_5225del(3) | c.8754+1G>T(1) | c.92G>A(1) | c.6468_6469del(1) | c.2990T>G(1) | |

| Philippines | 1 | 1 | c.2023del(1) | |||||

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | c.7977−1G>C(1) | |||||

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | c.473C>A(1) | |||||

| Singapore | 10 | 10 | c.200_1910−877dup(1) | c.2808_2811del(1) | c.8961_8964del(1) | c.8915del(1) | c.956dup(1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Australia | Australia | 496 | 178 | c.5946del(53) | c.6275_6276del(25) | c.7977−1G>C(11) | c.5682C>G(10) | c.3487_3848del(10) |

|

| ||||||||

| Europe | Austria | 185 | 87 | c.8364G>A(17) | c.8755−1G>A(15) | c.3860del(11) | c.1813dup(8) | c.7846del(6) |

| Belgium | 116 | 39 | c.6275_6276del(17) | c.516+1G>T(16) | c.8904del(14) | c.1389_1390del(9) | c.3847_3848del(7) | |

| Czech Republic. | 81 | 42 | c.8537_8538del(12) | c.7913_7917del(5) | c.5645C>A(4) | c.2808_2811del(4) | c.9403del(4) | |

| Denmark | 442 | 101 | c.7617+1G>A(61) | c.6373del(44) | c.1310_1313del (25) | c.6486_6489del(25) | c.3847_3848del(16) | |

| Finland | 52 | 16 | c.9118−2A>G(18) | c.7480C>T(12) | c.771_775del(7) | c.8327T>G(2) | c.1286T>G(2) | |

| France | 997 | 375 | c.2808_2811del(34) | c.5946del(27) | c.9026_9030del(22) | c.8364G>A(22) | c.5909C>A(19) | |

| Germany | 1,109 | 367 | c.1813dup(51) | c.3847_3848del(34) | c.2808_2811del(29) | c.5946del(29) | c.5682C>G(23) | |

| Greece | 28 | 22 | c.7976G>A(3) | c.5722_5723del(2) | c.9097dup(2) | c.9501+1G>A(2) | c.5722_5723del(2) | |

| Hungary | 81 | 39 | c.9097dup(17) | c.5946del(11) | c. 7913_7917del(4) | c.6656C>G(3) | c.9403del(3) | |

| Iceland | 89 | 1 | c.771_775del(89) | |||||

| Ireland | 2 | 2 | c.8951C>G(1) | c.5576_5579del(1) | ||||

| Italy | 706 | 242 | c.8878C>T(33) | c.6468_6469del(31) | c.7180A>T(29) | c.5682C>G(25) | c.8247_8248delGA(18) | |

| Lithuania | 26 | 11 | c.658_659del(13) | c.3847_3848del(4) | c.6580dup(1) | c.6410del(1) | c.7879A>T(1) | |

| Netherlands | 493 | 167 | c.6275_6276del(38) | c.8067T>A(26) | c.5946del(25) | c.9672dupA(23) | c. 5213_5216del (21) | |

| Norway | 2 | 1 | c.771_775del(2) | |||||

| Poland | 23 | 20 | c.5946del(3) | c.8946del(2) | c. 7913_7917del(1) | c.9294C>A(1) | c.635_636del(1) | |

| Portugal | 71 | 22 | c.156_157insAlu(39) | c.9097dup(5) | c.9382C>T(3) | c.682−2A>C(2) | c.5645G>A(2) | |

| Romania | 1 | 1 | c.9097dup(1) | |||||

| Russia | 3 | 3 | c.3682_3685del(1) | c.5410_5411del(1) | c.5946del(1) | |||

| Spain | 670 | 217 | c.3264dup(58) | c.2808_2811del(56) | c.9026_9030del(52) | c.6275_6276del(32) | c.9018C>A(16) | |

| Sweden | 123 | 68 | c.4258del(11) | c.2830A>T(7) | c.1796_1800del(6) | c.3847_3848del(6) | c.7558C>T5) | |

| UK | 1,200 | 308 | c.6275_6276del(107) | c.5946del(66) | c.4478_4481del(37) | c.755_758del(36) | c.5682C>G(33) | |

|

| ||||||||

| North America | Canada | 311 | 108 | c.8537_8538del(48) | c.5946del(45) | c.2808_2811del(13) | c.6275_6276del(11) | c.5857G>T(10) |

| USA | 3,064 | 626 | c.5946del(742) | c.2808_2811del(86) | c.1813dup(62) | c.658_659del(50) | c.6275_6276del(49) | |

|

| ||||||||

| South/Central America | Argentina | 49 | 21 | c.5946del(18) | c.2808_2811del(5) | c.6037A>T(4) | c.9026_9030del(2) | c.5645C>G(2) |

| Brazil | 47 | 33 | c.2T>G(5) | c.2808_2811del(4) | c.156_157insAlu(4) | c.6405_6409del(3) | c.1138del(2) | |

| Colombia | 19 | 4 | c.2808_2811del(15) | c.5851_5854del (2) | c.6275_6276del(1) | c.93G>A(1) | ||

| Costa Rica | 1 | 1 | c.9235del(1) | |||||

| Honduras | 1 | 1 | c.7558C>T(1) | |||||

| Mexico | 6 | 6 | c.3264dup (1) | c.6275_6276del (1) | c.2224C>T (1) | c.5542del (1) | c.6502G>T (1) | |

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The mutational distribution among the major racial/ethnic groups and by geography are summarized in Tables 4 and 5. Table 4 includes only those individuals for whom self-identified race/ethnicity was recorded. Note that in some countries it is prohibited to collect data on race and ethnicity, so this information is missing. Among the 10 most common BRCA1 mutations in each racial/ethnic group, a few were seen in several populations, including the recurrent Jewish and Eastern European founder mutations c.5266dup (5382insC) and c.68_69del (185delAG); c.815_824dup in African-Americans and Hispanics; c.3756_3759del in Caucasian and Jews; and c.5503C>T and c.3770_3771del in Asians and Jews. Similarly, recurrent mutations in BRCA2 included c.5946del (6174delT) in whites and Jews; c.2808_2811del in whites, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and Jews; c.6275_6276del in whites and Hispanics; c.3847_3848del in whites and Jews; c.658_659del in African Americans and Hispanics; and c.3264dup in Hispanics and Jews. The majority of other recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations were only observed within a single racial/ethnic group, particularly African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics. Of note, the vast majority of women who self-identified as Jewish carry the Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutations BRCA1 c.5266dup and c.68_69del and BRCA2 c.5946del. Only 72 (3.9%) of 1,852 BRCA1 mutation carrier families and 55 (5.6%) of 990 BRCA2 mutation carrier families who self-identified as being Jewish carried other (non-founder) mutations. However, since many individuals of self-identified Jewish ancestry are only tested for the three founder mutations, this number is likely to be underestimated.

Table 4.

Ten Most Frequently Observed Mutations by Self-Identified Race/Ethnicity (%) (by Family)

| Mutation Rank | Caucasian | African American | Asian | Hispanic/Latino | Jewish | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | 1 | c.5266dup(17%) | c.815_824dup(16%) | c.390C>A(4%) | c.68_69del(12%) | c.68_69del(72%) | c.5266dup(12%) |

| 2 | c.181T>G (6%) | c.5324T>G (7%) | c.5496_5506delinsA (3%) | c.3331_3334del(10%) | c.5266dup(24%) | c.68_69del(17%) | |

| 3 | c.68_69del(6%) | c.5177_5180del(5%) | c.470_471del(3%) | c.5123C>A(9%) | c.3756_3759del (0.3%) | c.181T>G(5%) | |

| 4 | c.4035del(2%) | c.4357+1G>A(5%) | c.5503C>T(2%) | c.548−?_4185+?del(7%) | c.1757del(0.3%) | c.5333−36_5406+400del(3%) | |

| 5 | c.4065_4068del(2%) | c.190T>G(3%) | c.922_924delinsT(2%) | c.211A>G(5%) | c.2934T>G(0.2%) | c.3481_3491del(2%) | |

| 6 | c.3756_3759del(2%) | c.68_69del(3%) | c.68_69del(2%) | c.815_824del(3%) | c.5503C>T(0.1%) | c.1687C>T (2%) | |

| 7 | c.1687C>T(2%) | c.5467+1G>A(3%) | c.3770_3771del(2%) | c.2433del(3%) | c.4185+1G>T(0.1%) | c.4065_4068del(2%) | |

| 8 | c.4327C>T(2%) | c.182G>A(3%) | c.2635G>T(2%) | c.1960A>T(3%) | c.4689C>G(0.1%) | c.5277+1G>A (2%) | |

| 9 | c.2475del(2%) | c.5251C>T(2%) | c.2726dup(2%) | c.3029_3030del(3%) | c.3770_3771del (0.1%) | c.2685_2686del(68%) | |

| 10 | c.4186−?_4357+?dup(1%) | c.4484G>T(2%) | c.3627dup(2%) | c.4327C>T(2%) | c.4936del(0.1%) | c.4327C>T(1%) | |

|

| |||||||

| Families | 11,258 | 174 | 550 | 408 | 1,852 | 4,583 | |

| Unique Mutations | 1,206 | 77 | 240 | 104 | 56 | 765 | |

|

| |||||||

| BRCA2 | 1 | c.5946del(5%) | c.2808_2811del(6%) | c.7480C>T(8%) | c.3264dup(17%) | c.5946del(94%) | c.5946del(5%) |

| 2 | c.6275_6276del(3%) | c.4552del(6%) | c.3109C>T(6%) | c.2808_2811del(9%) | c.3847_3848del (0.4%) | c.6275_6276del(4%) | |

| 3 | c.2808_2811del(3%) | c.9382C>T(5%) | c.3744_3747del(4%) | c.145G>T(5%) | c.1754del(0.4%) | c.2808_2811del(3%) | |

| 4 | c.771_775del(2%) | c.1310_1313del(4%) | c.1399A>T(3%) | c.9026_9030del(3%) | c.9382C>T(0.3%) | c.1813dup(3%) | |

| 5 | c.3847_3848del(2%) | c.5616_5620del(4%) | c.5576_5579del(3%) | c.658_659del(3%) | c.5621_5624del (0.2%) | c.5645C>A(2%) | |

| 6 | c.5682C>G(2%) | c.6405_6409del(3%) | c.2808_2811del(2%) | c.5542del(3%) | c.2808_2811del (0.2%) | c.1310_1313del(2%) | |

| 7 | c.1813dup(2%) | c.658_659del(3%) | c.7878G>A(2%) | c.3922G>T(3%) | c.4829_4830del (0.2%) | c.3847_3848del(2%) | |

| 8 | c.8537_8538del(1%) | c.2957_2958insG(2%) | c.262_263del(2%) | c.1813dup(2%) | c.5238del(0.2%) | c.5682C>G(1%) | |

| 9 | c.658_659del(1%) | c.7024C>T(2%) | c.7133C>G(1%) | c.9699_9702del(2%) | c.9207T>A(0.1%) | c.9672dup(1%) | |

| 10 | c.7934del(1%) | c.6531_6534del(2%) | c.5164_5165del(1%) | c.6275_6276del(@5) | c.3264dup(0.1%) | c.658_659del(1%) | |

|

| |||||||

| Families | 7,156 | 125 | 538 | 207 | 990 | 2,551 | |

| Unique Mutations | 1,242 | 77 | 248 | 91 | 44 | 753 | |

Table 5.

Ten Most Frequently Observed Mutations by Continent of Ascertainment (%) (by Family)

| Mutation Rank |

North America | Africa | Asia | South/Central America |

Europe | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | 1 | c.68_69del(26%) | c.2641G>T(26%) | c.68_69del(47%) | c.3331_3334del (20%) | c.5266dup(17%) | c.68_69del(10%) |

| 2 | c.5266dup(13%) | c.5266dup(10%) | c.5266dup(14%) | c.5266dup(16%) | c.181T>G(7%) | c.5266dup(8%) | |

| 3 | c.181T>G(3%) | c.1374del(6%) | c.390C>A(2%) | c.68_69del(9%) | c.68_69del(4%) | c.4065_4068del(4%) | |

| 4 | c.4327C>T(2%) | c.68_69del(6%) | c.5496_5506delinsA (2%) | c.5123C>A(8%) | c.4035del(2%) | c.3756_3759del(4%) | |

| 5 | c.4065_4068del(1%) | c.3228_3229del(6%) | c.5503C>T(1%) | c.211A>G(5%) | c.1687C>T(2%) | c.5503C>T(3%) | |

| 6 | c.3756_3759del(1%) | c.303T>G(6%) | c.2934T>G(1%) | c.181T>G(3%) | c.4065_4068del(2%) | c.4186−?_4357+?dup(3%) | |

| 7 | c.213−11T>G(1%) | c.4838_4839insC (3%) | c.3770_3771del(1%) | c.548−?_4183+8?del(3%) | c.3481_3491del(1%) | c.4327C>T(2%) | |

| 8 | c.1687C>T(1%) | c.3268C>T(3%) | c.2726dup(1%) | c.1687C>T(2%) | c.2475del(1%) | c.5278−?_5592+?del (2%) | |

| 9 | c.4186−?4357+?dup(1%) | c.1504_1508del(3%) | c.470_471del(1%) | c.135−?_441+?del(2%) | c.3756_3759del(1%) | c.70_80del(2%) | |

| 10 | c.1175_1214del(1%) | c.191G>A(3%) | c.922_924delinsT(1%) | c.5030_5033del (2%) | c.3770_3704del(1%) | c.1961del(2%) | |

|

| |||||||

| Families | 4,669 | 69 | 1,100 | 271 | 11,748 | 581 | |

| Unique Mutations | 654 | 30 | 187 | 75 | 1282 | 173 | |

|

| |||||||

| BRCA2 | 1 | c.5946del(23%) | c.7934del(47%) | c.5946del(34%) | c.2808_2811del (11%) | c.6275_6276del(2%) | c.5946del(5%) |

| 2 | c.2808_2811del(3%) | c.5946del(4%) | c.7480C>T(4%) | c.5946del(9%) | c.5946del(2%) | c.6275_6276del(2%) | |

| 3 | c.8537_8538del(2%) | c.1310_1313del(2%) | c.3109C>T(3%) | c.2T>G(2%) | c.2808_2811del(2%) | c.7977−1G>C(1%) | |

| 4 | c.1813dup(2%) | c.6944_6947del(1%) | c.3744_3747del(2%) | c.156_157insAlu (2%) | 771_775del(1%) | c.5682C>G(1%) | |

| 5 | c.6275_6276del(2%) | c.8817_8820del(1%) | c.1399A>T(2%) | c.6037A>T(2%) | c.3847_3848del(1%) | c.3847_3848del(1%) | |

| 6 | c.3847_3848del(3%) | c.5213_5216del(1%) | c.5576_5579del(2%) | c.6405_6409del(3) | c.1813dup(1%) | c.2808_2811del(1%) | |

| 7 | c.658_659del(2%) | c.6535_6536insA (1%) | c.2808_2811del(1%) | c.5645C>G(1%) | c.5682C>G(1%) | c.755_758del(1%) | |

| 8 | c.9382C>T(1%) | c.774_775del(1%) | c.262_263del(1%) | c.658_659del(1%) | c.1310_1313del(92) | c.4478_4481del(1%) | |

| 9 | c.3264dup(1%) | c.6393del(1%) | c.8537_8538del(1%) | c.7180A>T(1%) | c.5645C>A(1%) | c.8297del(1%) | |

| 10 | c.55073dup(1%) | c.5042_5043del(1%) | c.7878G>A(1%) | c.5851_5854del (1%) | c.9026_9030del(1%) | c.250C>T(1%) | |

|

| |||||||

| Families | 3,375 | 170 | 976 | 222 | 10,175 | 1,047 | |

| Unique Mutations | 660 | 27 | 187 | 58 | 1,315 | 179 | |

In African Americans, the majority of BRCA1 mutations were not observed in any other racial/ethnic group, implying these mutations may be of African origin. In Hispanics, the most common BRCA1 mutations also were observed among individuals from other regions who did not self-identify as Hispanic, including BRCA1 c.3331_3334del (also observed in Australia, Europe, USA, and the UK), and BRCA1 c.68_69del (the Jewish founder mutation) (Weitzel, et al., 2013; Weitzel, et al., 2005). The BRCA1 c.815_824dup mutation has been reported as being of African origin, but has also been reported as a recurrent mutation in Mexican-Americans, perhaps as a reflection of the complex continental admixture of this population (Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015b). BRCA1 c.390C>A and c.5496_5506delinsA were most commonly found in the Asian population. In BRCA2, c.2808_2811del was found among the 10 most frequent mutations in all races/ethnicities.

Recurrent Mutations

As expected, the most common mutations in the entire data set were the founder mutations BRCA1 c.5266dup (5382insC), BRCA1 c.68_69del (185delAG), and BRCA2 c.5946del (6174delT). In part, the high frequency of these mutations is a consequence of panels that facilitate testing for these three mutations in women of Jewish descent. However, these two BRCA1 mutations also are relatively common in regions with a low proportion of individuals who self-identify as Jewish (e.g., Hungary, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Poland Spain, Russia, and UK). BRCA1 c.5266dup is a founder mutation thought to have originated 1800 years ago in Scandinavia/Northern Russia, entering the Ashkenazi-Jewish population 400–500 years ago, and thus has origins and a spread pattern independent of the Ashkenazim (Hamel, et al., 2011). Haplotype studies have been used to determine the origin of BRCA1 c.68_69delAG in populations not considered to have a high proportion of Jewish ancestry. In some populations, such as the Hispanics in the USA and Latin American, it is associated with the Ashkenazi Jewish haplotype, presumably due to unrecognized (Jewish) ancestry (Ah Mew, et al., 2002; Velez, et al., 2012; Weitzel, et al., 2005). In other populations, such as Pakistani and Malaysians, where BRCA1 c.68_69del is a recurrent mutation, it appears to have arisen independently, as it is carried on a distinct haplotype (Kadalmani, et al., 2007; Rashid, et al., 2006). A different haplotype was also reported for several British families (the ‘Yorkshire haplotype’) that is distinct from both the Jewish and the Indian-Pakistani haplotypes (Laitman, et al., 2013; Neuhausen, et al., 1996).

The only locations in which these three founder mutations were not commonly observed were Belgium and Iceland. Iceland has another founder mutation (i.e., BRCA2 c.771_775del). Yet other founder mutations included BRCA1 c.4327C>T and BRCA2 c.8537_8538del in Quebec. This latter mutation in BRCA2 also is the most common mutation in high-risk families in Sardinia (Pisano, et al., 2000) and was also reported in a few Jewish Yemenite families, with a distinct haplotype(Palomba, et al., 2007). The BRCA1 c.181T>G mutation was observed in Central Europe (Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Poland), but also observed in the US, Argentina, Latvia, Lithuania and Israel. This mutation has been found on a common haplotype in individuals of Polish and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, suggesting it is an Eastern European founder mutation (Kaufman, et al., 2009). The large rearrangement mutation in BRCA1 c.548-?4185+?del (ex9-12del) appears to be an important founder mutation in Mexico, with findings of a common haplotype and an estimated age at 74 generations (~1,500 years) (Weitzel, et al., 2013).

We observed a number of other recurrent mutations. BRCA1 c.3331_3334del comprised more than half of all mutations identified in Colombia, consistent with a previous report that this is a founder mutation in the Colombian population (Torres, et al., 2007). However, this mutation has not been found at high rates in a second Colombian population (Cock-Rada, et al., 2017). BRCA2 c.2808_2811del was frequently observed, not only as the most common mutation in France and Colombia, but also in other Western and Southern European countries, and destinations to which individuals from these countries have migrated. It estimated to have arisen approximately 80 (46–134) generations ago. However, due to the diversity of the haplotypes, multiple independent origins could not be ruled out (Neuhausen, et al., 1998). BRCA2 c.6275_6276del was a recurrent BRCA2 mutation in Australia, the UK, Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands, and North America. This mutation has been estimated to have originated 52 (24–98) generations ago from a single founder (Neuhausen, et al., 1998). Recurrent or founder mutations were observed in diverse populations. For example, the c.115T>G (Cys39Gly) mutation has been described in Greenlanders (Hansen, et al., 2009). The c.2641G >T and c.7934del mutations have both been reported as founder mutation in South African Afrikaners (Reeves, et al., 2004).

DISCUSSION

We have reported worldwide distribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations curated in the CIMBA dataset. These results may aid in the understanding of the mutation distribution in specific populations as well as imparting clinical and biological implications for our understanding of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated carcinogenesis.

Clinical testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has benefited substantially from knowledge about common mutations in specific populations. In many countries, the three Ashkenazi-Jewish founder mutations are offered as a mutation testing panel for self-reported Ashkenazim, based on their frequency. This approach is much less expensive than comprehensive gene sequencing. The identification of commonly-occurring mutations in other populations could lead to more efficient and cost-effective mutation testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. For example, Villareal-Garza et al. (Villarreal-Garza, et al., 2015a) have developed the HISPANEL of mutations that optimizes testing in Hispanic/Latino populations. In the present study, we have identified mutations that may exist at a sufficient prevalence to warrant consideration for population-specific mutation testing panels. Criteria for developing such panels for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation screening are not available. However, mutations that are in a specific population and that capture a sufficient percentage of mutations in high risk individuals and families in that population may be appropriate for use in targeted genetic testing. Before such panels can be developed, population-based studies of mutation frequency in specific populations should be undertaken. The data reported herein provide a list of the recurrent mutations around which such panels could be developed, but the frequencies are not population-based, particularly in settings where founder mutations are preferentially screened (e.g., the Jewish founder panels). Similarly, putative founder mutations identified by assessing common ancestral origins of specific mutations (rather than just high prevalence; Table 5) may form the basis of population-specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation screening panels.

We report the distribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in nearly 30,000 families of bona-fide disease-associated mutations. The strengths of this report include the large sample size that reflects a geographically and racially/ethnically diverse set of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. However, some limitations need to be considered. First, the sample set presented here does not reflect a systematic study of these populations or races/ethnicities; the data reflect patterns of recruitment (e.g., individuals with higher risk or prior diagnosis of cancer who consented to participate in research protocols) that contributed to the CIMBA consortium. Certain racial/ethnic or socio-demographic groups are under- or over-represented or missing in our data set and, as a consequence, mutations may be over- or under-represented. For example, the existence of a commercial panel of three Jewish founder mutations enhances genetic testing for those mutations. As a result, the most frequently observed mutations in some populations (e.g., the USA) reflect the widespread use of this testing panel in the USA population. Similar arguments may also apply for other populations, where testing for certain founder mutations may be more frequent. Therefore the relative frequencies of mutations by population in the present study may be subject to such testing biases. Comparing the relative frequencies is also complicated by the inclusion of related individuals.

Second, although the CIMBA data represent most regions around the world, there are limitations related to which groups of individuals have been tested and which centers contributed data. In particular, non-white ancestry populations are still under-represented in research reports of mutation spectrum and frequency. Genetic testing in the developing world remains limited.

Third, we presented the mutations in terms of type or effect (Table 1), but these designations are not always based on experimental evidence. For example, NMD mutation status is almost always defined by a prediction rule rather than in vitro experiments that confirm the presence of nonsense mediated decay.

Fourth, we presented the occurrence of putative founder mutations. Some of these founder mutations (e.g., BRCA1 c.68_69del, BRCA2 c.771_775del) have been demonstrated to be true founder mutations based on actual ancestry analyses. Others, however, have only been identified as occurring commonly in certain populations, but haplotype or similar analyses of founder status may not have been done.

Fifth, our analysis was based on self-reported race/ethnicity of study participants, but this information may misclassify some groups of individuals. For example, some Middle Eastern groups may have been classified as “Caucasian” based on the data available, but in fact may represent a distinct group that was not captured here. Moreover, in some large centers participating in CIMBA, collecting information on race/ethnicity is prohibited and these mutation carriers were excluded from the comparisons.

Finally, we evaluated mutations by racial/ethnic and geographic designations, but some of these may be misclassified. For example, while BRCA1 c.68_69del has been shown to arise independently of the Jewish founder mutation in Pakistan (Rashid, et al., 2006), we cannot determine if the identified group also contains some Ashkenazi Jewish individuals.

The data presented herein provide new insights into the worldwide distribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. The identification of recurrent mutations in some racial/ethnic groups or geographical locations raises the possibility of defining more efficient strategies for genetic testing. Three Jewish founder mutations BRCA1 c.5266dup (5382insC) and BRCA1 c.68_69del (185delAG) and BRCA2 c.5946del (6174delT) have long been used as a primary genetic screening test for women of Jewish descent. The identification here of other recurrent mutations in specific populations may similarly provide the basis for other mutation-specific panels. For example, BRCA1 c.5266dup (5382insC) may be a useful as a single mutation screening test in Central-Eastern European populations before undertaking full sequencing. However, this basic test may be supplemented with screening for BRCA1 c.181T>G, as the second most common mutation of the region, and for some special cases, to include most common Hungarian BRCA2 founder mutation c.9097dup (9326insA) for those with Hungarian ancestry (van der Looij, et al., 2000, Ramus, et al., 1997b). In Iceland, only two mutations were reported: the founder mutation BRCA2 c.771_775del and the rarer BRCA1 c.5074G>A (Bergthorsson, et al., 1998). A number of other situations can be identified in which specific mutations explain a large proportion of the total mutations observed in a population. These and other such examples suggest that targeted mutation testing panels which include specific mutations could be developed for use in specific populations. Finally, we focused on female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers in this report. However, the growing knowledge about BRCA1 and BRCA2-associated cancers in men, particularly prostate cancer (Ostrander and Udler, 2008; Pritchard, et al., 2016), suggests that the information presented herein will also have value in genetic testing of men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

United States NIH, including NCI, funding supported the research presented in this manuscript.

| Study | Funding | Acknowledgements |

|---|---|---|

| CIMBA | The CIMBA data management and data analysis were supported by Cancer Research – UK grants C12292/A20861, C12292/A11174. ACA is a Cancer Research -UK Senior Cancer Research Fellow. GCT and ABS are NHMRC Research Fellows. iCOGS: the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement n° 223175 (HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (COGS), Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118, C1287/A 10710, C12292/A11174, C1281/A12014, C5047/A8384, C5047/A15007, C5047/A10692, C8197/A16565), the National Institutes of Health (CA128978) and Post-Cancer GWAS initiative (1U19 CA148537, 1U19 CA148065 and 1U19 CA148112 - the GAME-ON initiative), the Department of Defence (W81XWH-10-1-0341), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer (CRN-87521), and the Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade (PSR-SIIRI-701), Komen Foundation for the Cure, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund. The PERSPECTIVE project was supported by the Government of Canada through Genome Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ministry of Economy, Science and Innovation through Genome Québec, and The Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation. | All the families and clinicians who contribute to the studies; Sue Healey, in particular taking on the task of mutation classification with the late Olga Sinilnikova; Maggie Angelakos, Judi Maskiell, Gillian Dite, Helen Tsimiklis |

| BCFR - all | This Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR) is supported by grant UM1 CA164920 from the USA National Cancer Institute. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centers in the BCFR, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the USA Government or the BCFR. | |

| BCFR-AU | Maggie Angelakos, Judi Maskiell, Gillian Dite, Helen Tsimiklis. | |

| BCFR-NY | We wish to thank members and participants in the New York site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry for their contributions to the study. | |

| BCFR-ON | We wish to thank members and participants in the Ontario Familial Breast Cancer Registry for their contributions to the study. | |

| BFBOCC-LT | BFBOCC is partly supported by: Lithuania (BFBOCC-LT): Research Council of Lithuania grant SEN-18/2015 | BFBOCC-LT acknowledge Laimonas Griškevičius. BFBOCC-LV acknowledge Drs Janis Eglitis, Anna Krilova and Aivars Stengrevics. |

| BIDMC | BIDMC is supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation | |

| BMBSA | BRCA-gene mutations and breast cancer in South African women (BMBSA) was supported by grants from the Cancer Association of South Africa (CANSA) to Elizabeth J. van Rensburg | BMBSA wish to thank the families who contribute to the BMBSA study |

| BRICOH | SLN was partially supported by the Morris and Horowitz Families Endowed Professorship. | |

| CEMIC | This work is funded by CONICET and Instituto Nacional del Cancer, Ministerio de Salud de la Nacion Argentina (1995/15) | We thank to Florencia Cardoso, Natalia Liria and Pablo Mele in their biospecimen and data management. |

| CNIO | CNIO study is partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health PI16/00440 supported by FEDER funds, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) SAF2014-57680-R and the Spanish Research Network on Rare diseases (CIBERER) | We thank Alicia Barroso, Rosario Alonso and Guillermo Pita for their assistance. |

| COH-CCGCRN | City of Hope Clinical Cancer Genomics Community Network and the Hereditary Cancer Research Registry, supported in part by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, by Award Number RC4CA153828 (PI: J. Weitzel) from the National Cancer Institute and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, and by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25CA171998 (PIs: K. Blazer and J. Weitzel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health | |

| CONSIT TEAM | Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; IG2014 no.15547) to P. Radice; Funds from Italian citizens who allocated the 5×1000 share of their tax payment in support of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori, according to Italian laws (INT-Institutional strategic projects ‘5×1000’) to S Manoukian; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro IG17734; Italian Ministry of University and Research, PRIN projects; Istituto Pasteur-Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti to G. Giannini ; FiorGen Foundation for Pharmacogenomics to L. Papi ; Funds from Italian citizens who allocated the 5×1000 share of their tax payment in support of the IRCCS AOU San Martino - IST according to Italian laws (institutional project) to L. Varesco ; Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; IG2015 no.16732) to P. Peterlongo | Bernard Peissel, Milena Mariani and Daniela Zaffaroni of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy; Davide Bondavalli, Maria Rosaria Calvello and Irene Feroce of the Istituto Europeo di Oncologia, Milan, Italy; Alessandra Viel and Riccardo Dolcetti of the CRO Aviano National Cancer Institute, Aviano (PN), Italy; Francesca Vignolo-Lutati of the University of Turin, Turin, Italy; Gabriele Capone of the University of Florence, Florence, Italy; Laura Ottini of the "Sapienza" University, Rome, Italy; Viviana Gismondi of the IRCCS AOU San Martino – IST, Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Genoa, Italy; Maria Grazia Tibiletti and Daniela Furlan of the Ospedale di Circolo-Università dell'Insubria, Varese, Italy; Antonella Savarese and Aline Martayan of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori Regina Elena, Rome, Italy; Stefania Tommasi and Brunella Pilato of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori "Giovanni Paolo II" - Bari, Italy, and the personnel of the Cogentech Cancer Genetic Test Laboratory, Milan, Italy. |

| DFCI | This research has been supported by R01-CA08534 and R01-CA102776 to TRR. | |

| DEMOKRITOS | This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund – ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program "Education and Lifelong Learning" of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) - Research Funding Program of the General Secretariat for Research & Technology: SYN11_10_19 NBCA. Investing in knowledge society through the European Social Fund. | |

| DKFZ | The DKFZ study was supported by the DKFZ and in part by the SKMCH & RC, Lahore, Pakistan and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogota, Colombia. | We thank all participants, clinicians, family doctors, researchers, and technicians for their contributions and commitment to the DKFZ study and the collaborating groups in Lahore, Pakistan (Noor Muhammad, Sidra Gull, Seerat Bajwa, Faiz Ali Khan, Humaira Naeemi, Saima Faisal, Asif Loya, Mohammed Aasim Yusuf) and Bogota, Colombia (Ignacio Briceno, Fabian Gil). |

| EMBRACE | EMBRACE is supported by Cancer Research UK Grants C1287/A10118 and C1287/A11990. D. Gareth Evans and Fiona Lalloo are supported by an NIHR grant to the Biomedical Research Centre, Manchester. The Investigators at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust are supported by an NIHR grant to the Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. Ros Eeles and Elizabeth Bancroft are supported by Cancer Research UK Grant C5047/A8385. Ros Eeles is also supported by NIHR support to the Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust | RE is supported by NIHR support to the Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust |

| FCCC | The authors acknowledge support from The University of Kansas Cancer Center (P30 CA168524) and the Kansas Bioscience Authority Eminent Scholar Program. A.K.G. was funded by 5U01CA113916, R01CA140323, and by the Chancellors Distinguished Chair in Biomedical Sciences Professorship. | We thank Ms. JoEllen Weaver and Dr. Betsy Bove for their technical support. |

| FPGMX | This work was partially supported by FISPI05/2275 and Mutua Madrileña Foundation (FMMA). | We would like to thank Marta Santamariña, Ana Blanco, Miguel Aguado, Uxía Esperón and Belinda Rodríguez for their contribution with the study. |

| GC-HBOC | The German Consortium of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (GC-HBOC) is supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant no 110837), Rita K. Schmutzler. | The Regensburg HBOC thanks Dr. Ivana Holzhauser and Dr. Ines Schönbuchner for their contributions to the study |

| GEMO | The study was supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; the Association “Le cancer du sein, parlons-en!” Award; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for the "CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer" program and the French National Institute of Cancer (INCa). | Genetic Modifiers of Cancer Risk in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation Carriers (GEMO) study : National Cancer Genetics Network «UNICANCER Genetic Group», France. We wish to pay a tribute to Olga M. Sinilnikova, who with Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet initiated and coordinated GEMO until she sadly passed away on the 30th June 2014, and to thank all the GEMO collaborating groups for their contribution to this study. GEMO Collaborating Centers are: Coordinating Centres, Unité Mixte de Génétique Constitutionnelle des Cancers Fréquents, Hospices Civils de Lyon - Centre Léon Bérard, & Equipe «Génétique du cancer du sein», Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Lyon: Olga Sinilnikova†, Sylvie Mazoyer, Francesca Damiola, Laure Barjhoux, Carole Verny-Pierre, Mélanie Léone, Nadia Boutry-Kryza, Alain Calender, Sophie Giraud; and Service de Génétique Oncologique, Institut Curie, Paris: Claude Houdayer, Etienne Rouleau, Lisa Golmard, Agnès Collet, Virginie Moncoutier, Muriel Belotti, Camille Elan, Catherine Nogues, Emmanuelle Fourme, Anne-Marie Birot. Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif: Brigitte Bressac-de-Paillerets, Olivier Caron, Marine Guillaud-Bataille. Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont–Ferrand: Yves-Jean Bignon, Nancy Uhrhammer. Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon: Christine Lasset, Valérie Bonadona, Sandrine Handallou. Centre François Baclesse, Caen: Agnès Hardouin, Pascaline Berthet, Dominique Vaur, Laurent Castera. Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille: Hagay Sobol, Violaine Bourdon, Tetsuro Noguchi, Audrey Remenieras, François Eisinger. CHU Arnaud-de-Villeneuve, Montpellier: Isabelle Coupier, Pascal Pujol. Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille: Jean-Philippe Peyrat, Joëlle Fournier, Françoise Révillion, Philippe Vennin†, Claude Adenis. Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg: Danièle Muller, Jean-Pierre Fricker. Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux: Emmanuelle Barouk-Simonet, Françoise Bonnet, Virginie Bubien, Nicolas Sevenet, Michel Longy. Institut Claudius Regaud, Toulouse: Christine Toulas, Rosine Guimbaud, Laurence Gladieff, Viviane Feillel. CHU Grenoble: Dominique Leroux, Hélène Dreyfus, Christine Rebischung, Magalie Peysselon. CHU Dijon: Fanny Coron, Laurence Faivre. CHU St-Etienne: Fabienne Prieur, Marine Lebrun, Caroline Kientz. Hôtel Dieu Centre Hospitalier, Chambéry: Sandra Fert Ferrer. Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice: Marc Frénay. CHU Limoges: Laurence Vénat-Bouvet. CHU Nantes: Capucine Delnatte. CHU Bretonneau, Tours: Isabelle Mortemousque. Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris: Florence Coulet, Chrystelle Colas, Florent Soubrier, Mathilde Warcoin. CHU Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy: Johanna Sokolowska, Myriam Bronner. CHU Besançon: Marie-Agnès Collonge-Rame, Alexandre Damette. Creighton University, Omaha, USA: Henry T. Lynch, Carrie L. Snyder. |

| GEORGETOWN | CI received support from the Non-Therapeutic Subject Registry Shared Resource at Georgetown University (NIH/NCI grant P30-CA051008), the Fisher Center for Familial Cancer Research, and Swing Fore the Cure. | |

| HCBARRETOS | This study was supported by Barretos Cancer Hospital, FINEP - CT-INFRA (02/2010) and FAPESP (2013/24633-2). | We wish to thank members of the Center of Molecular Diagnosis, Oncogenetics Department and Molecular Oncology Research Center of Barretos Cancer Hospital for their contributions to the study. |

| G-FAST | Bruce Poppe is a senior clinical investigator of FWO. Mattias Van Heetvelde obtained funding from IWT. | We wish to thank the technical support of Ilse Coene en Brecht Crombez. |

| HCSC | Was supported by a grant RD12/0036/0006 and 15/00059 from ISCIII (Spain), partially supported by European Regional Development FEDER funds | We acknowledge Alicia Tosar and Paula Diaque for their technical assistance |

| HEBCS | The HEBCS was financially supported by the Helsinki University Hospital Research Fund, Academy of Finland (266528), the Finnish Cancer Society and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation. | HEBCS would like to thank Taru A. Muranen and Johanna Kiiski, Drs. Carl Blomqvist and Kirsimari Aaltonen and RNs Irja Erkkilä and Virpi Palola for their help with the HEBCS data and samples. HEBCS would like to thank Dr. Kristiina Aittomäki, Taru A. Muranen, Drs. Carl Blomqvist and Kirsimari Aaltonen and RNs Irja Erkkilä and Virpi Palola for their help with the HEBCS data and samples. |

| HEBON | The HEBON study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society grants NKI1998-1854, NKI2004-3088, NKI2007-3756, the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research grant NWO 91109024, the Pink Ribbon grants 110005 and 2014-187.WO76, the BBMRI grant NWO 184.021.007/CP46 and the Transcan grant JTC 2012 Cancer 12-054. HEBON thanks the registration teams of Dutch Cancer Registry (IKNL; S. Siesling, J. Verloop) and the Dutch Pathology database (PALGA; L. Overbeek) for part of the data collection. | The Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON) consists of the following Collaborating Centers: Coordinating center: Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, NL: M.A. Rookus, F.E. van Leeuwen, S. Verhoef, M.K. Schmidt, N.S. Russell, J.L. de Lange, R. Wijnands; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, NL: J.M. Collée, A.M.W. van den Ouweland, M.J. Hooning, C. Seynaeve, C.H.M. van Deurzen, I.M. Obdeijn; Leiden University Medical Center, NL: J.T. Wijnen, R.A.E.M. Tollenaar, P. Devilee, T.C.T.E.F. van Cronenburg; Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, NL: C.M. Kets; University Medical Center Utrecht, NL: M.G.E.M. Ausems, R.B. van der Luijt, C.C. van der Pol; Amsterdam Medical Center, NL: C.M. Aalfs, T.A.M. van Os; VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, NL: J.J.P. Gille, Q. Waisfisz; Maastricht University Medical Center:University Hospital Maastricht, NL: E.B. Gómez-Garcia; University Medical Center Groningen, NL: J.C. Oosterwijk, A.H. van der Hout, M.J. Mourits, G.H. de Bock; The Netherlands Foundation for the detection of hereditary tumours, Leiden, NL: H.F. Vasen; The Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL): S. Siesling, J.Verloop; The Dutch Pathology Registry (PALGA): L.I.H. Overbeek. |

| HRBCP | HRBCP is supported by The Hong Kong Hereditary Breast Cancer Family Registry and the Dr. Ellen Li Charitable Foundation, Hong Kong | We wish to thank Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital for their continued support |

| HUNBOCS | Hungarian Breast and Ovarian Cancer Study was supported by Hungarian Research Grants KTIA-OTKA CK-80745, NKFIH/ OTKA K-112228 and the Norwegian EEA Financial Mechanism Hu0115/NA/2008-3/OP-9 | We wish to thank the Hungarian Breast and Ovarian Cancer Study Group members (Janos Papp, Tibor Vaszko, Aniko Bozsik, Timea Pocza, Zoltan Matrai, Gabriella Ivady, Judit Franko, Maria Balogh, Gabriella Domokos, Judit Ferenczi, Department of Molecular Genetics, National Institute of Oncology, Budapest, Hungary) and the clinicians and patients for their contributions to this study. |

| HVH | We wish to thank the Oncogenetics Group (VHIO) and the High Risk and Cancer Prevention Unit of the University Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Acknowledgements to the Cellex Foundation for providing research facilities and equipment. | |

| ICO | The authors would like to particularly acknowledge the support of the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (organismo adscrito al Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad) and “Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), una manera de hacer Europa” (PI10/01422, PI13/00285, PIE13/00022, PI15/00854, PI16/00563 and CIBERONC) and the Institut Català de la Salut and Autonomous Government of Catalonia (2009SGR290, 2014SGR338 and PERIS Project MedPerCan). ICO: Contract grant sponsor: Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer, Spanish Health Research Fund; Carlos III Health Institute; Catalan Health Institute and Autonomous Government of Catalonia. Contract grant numbers: ISCIIIRETIC RD06/0020/1051, RD12/0036/008, PI10/01422, PI10/00748, PI13/00285, PIE13/00022, 2009SGR290 and 2014SGR364. | We wish to thank the ICO Hereditary Cancer Program team led by Dr. Gabriel Capella. |

| IHCC | The IHCC was supported by Grant PBZ_KBN_122/P05/2004 | |

| ILUH | The ILUH group was supported by the Icelandic Association “Walking for Breast Cancer Research” and by the Landspitali University Hospital Research Fund. | |

| INHERIT | This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for the “CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer” program, the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance-grant #019511 and the Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade – grant # PSR-SIIRI-701. | We would like to thank Dr Martine Dumont, Martine Tranchant for sample management and skillful technical assistance. J.S. is Chairholder of the Canada Research Chair in Oncogenetics. J.S. and P.S. were part of the QC and Genotyping coordinating group of iCOGS (BCAC and CIMBA). |

| IOVCHBOCS | IOVCHBOCS is supported by Ministero della Salute and “5×1000” Istituto Oncologico Veneto grant. | |

| IPOBCS | This study was in part supported by Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro. | We wish to thank Drs. Catarina Santos, Patrícia Rocha and Pedro Pinto for their skillful contribution to the study. |

| KCONFAB | kConFab is supported by a grant from the National Breast Cancer Foundation, and previously by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Queensland Cancer Fund, the Cancer Councils of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the Cancer Foundation of Western Australia; Amanda Spurdle is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship. | We wish to thank Heather Thorne, Eveline Niedermayr, all the kConFab research nurses and staff, the heads and staff of the Family Cancer Clinics, and the Clinical Follow Up Study (which has received funding from the NHMRC, the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Cancer Australia, and the National Institute of Health (USA)) for their contributions to this resource, and the many families who contribute to kConFab. |

| KOHBRA | KOHBRA is partially supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (1020350 &1420190). | |

| MAYO | MAYO is supported by NIH grants CA116167, CA128978 and CA176785, an NCI Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (CA116201), a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and a generous gift from the David F. and Margaret T. Grohne Family Foundation. | |

| MCGILL | Jewish General Hospital Weekend to End Breast Cancer, Quebec Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade | |

| MODSQUAD | MODSQUAD was supported by MH CZ - DRO (MMCI, 00209805) and by the European Regional Development Fund and the State Budget of the Czech Republic (RECAMO, CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0101) to LF, and by Charles University in Prague project UNCE204024 (MZ). | Modifier Study of Quantitative Effects on Disease (MODSQUAD): MODSQUAD acknowledges ModSQuaD members and Michal Zikan, Petr Pohlreich and Zdenek Kleibl (Oncogynecologic Center and Department of Biochemistry and Experimental Oncology, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic). |

| MUV | We wish to thank Daniela Muhr and the Senology team, and the clinicians and patients for their contributions to this study. | |

| MSKCC | MSKCC is supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Robert and Kate Niehaus Clinical Cancer Genetics Initiative, the Andrew Sabin Research Fund. and the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. | Anne Lincoln, Lauren Jacobs |

| MUV | We wish to thank Daniela Muhr and the Senology team, and the clinicians and patients for their contributions to this study. | |

| NCCS | Dr J Ngeow is supported by grants from National Medical Research Council of Singapore; Ministry of Health Health Services Research Grant Singapore and Lee Foundation Singapore | We would like to thank all patients, families and clinicians who contributed data and time to this study. |

| NCI | The research of Drs. MH Greene, PL Mai, and JT Loud was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Cancer Institute, NIH, and by support services contracts NO2-CP-11019-50 and N02-CP-65504 with Westat, Inc, Rockville, MD. | |

| NNPIO | This work has been supported by the Russian Federation for Basic Research (grants 14-04-93959 and 15-04-01744). | |

| Northshore | We would like to thank Wendy Rubinstein and the following genetic counselors for help with participant recruitment: Scott Weissman, Anna Newlin, Kristen Vogel, Lisa Dellafave-Castillo, Shelly Weiss. | |

| NRG Oncology | This study was supported by NRG Oncology Operations grant number U10 CA180868 as well as NRG SDMC grant U10 CA180822, Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Administrative Office and the GOG Tissue Bank (CA 27469) and the GOG Statistical and Data Center (CA 37517). Drs. Greene, Mai and Loud were supported by funding from the Intramural Research Program, NCI. | We thank the investigators of the Australia New Zealand NRG Oncology group |

| OCGN | We wish to thank members and participants in the Ontario Cancer Genetics Network for their contributions to the study. | |

| OSU CCG | OSUCCG is supported by the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. | Kevin Sweet, Caroline Craven, Julia Cooper, and Michelle O'Conor were instrumental in accrual of study participants, ascertainment of medical records and database management. |

| PBCS | This work was supported by the ITT (Istituto Toscano Tumori) grants 2011–2013. | |

| SEABASS | Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Ministry of Higher Education (UM.C/HlR/MOHE/06) and Cancer Research Initiatives Foundation | We would like to thank Yip Cheng Har, Nur Aishah Mohd Taib, Phuah Sze Yee, Norhashimah Hassan and all the research nurses, research assistants and doctors involved in the MyBrCa Study for assistance in patient recruitment, data collection and sample preparation. In addition, we thank Philip Iau, Sng Jen-Hwei and Sharifah Nor Akmal for contributing samples from the Singapore Breast Cancer Study and the HUKM-HKL Study respectively. The Malaysian Breast Cancer Genetic Study is funded by research grants from the Malaysian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Ministry of Higher Education (UM.C/HIR/MOHE/06) and charitable funding from Cancer Research Initiatives Foundation. |

| SMC | This project was partially funded through a grant by the Israel cancer association and the funding for the Israeli Inherited breast cancer consortium | SMC team wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the Meirav Comprehensive breast cancer center team at the Sheba Medical Center for assistance in this study. |

| SWE-BRCA | SWE-BRCA collaborators are supported by the Swedish Cancer Society | Swedish scientists participating as SWE-BRCA collaborators are: from Lund University and University Hospital: Åke Borg, Håkan Olsson, Helena Jernström, Karin Henriksson, Katja Harbst, Maria Soller, Ulf Kristoffersson; from Gothenburg Sahlgrenska University Hospital: Margareta Nordling, Per Karlsson, Zakaria Einbeigi; from Stockholm and Karolinska University Hospital: Annika Lindblom, Brita Arver, Gisela Barbany Bustinza, Johanna Rantala; from Umeå University Hospital: Beatrice Melin, Christina Edwinsdotter Ardnor, Monica Emanuelsson; from Uppsala University: Maritta Hellström Pigg, Richard Rosenquist; from Linköping University Hospital: Marie Stenmark-Askmalm, Sigrun Liedgren |

| UCHICAGO | UCHICAGO is supported by NCI Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (CA125183), R01 CA142996, 1U01CA161032 and by the Ralph and Marion Falk Medical Research Trust, the Entertainment Industry Fund National Women's Cancer Research Alliance and the Breast Cancer research Foundation. OIO is an ACS Clinical Research Professor. | We wish to thank Cecilia Zvocec, Qun Niu, physicians, genetic counselors, research nurses and staff of the Cancer Risk Clinic for their contributions to this resource, and the many families who contribute to our program. |

| UCLA | Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Foundation; Breast Cancer Research Foundation | We thank Joyce Seldon MSGC and Lorna Kwan, MPH for assembling the data for this study. |

| UCSF | UCSF Cancer Risk Program and Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center | We would like to thank the following genetic counselors for participant recruitment: Beth Crawford, Kate Loranger, Julie Mak, Nicola Stewart, Robin Lee, and Peggy Conrad. And thanks to Ms. Salina Chan for her data management. |

| UKFOCR | UKFOCR was supported by a project grant from CRUK to Paul Pharoah. | We thank Simon Gayther, Carole Pye, Patricia Harrington and Eva Wozniak for their contributions towards the UKFOCR. |

| UPENN | National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-CA102776 and R01-CA083855; Breast Cancer Research Foundation; Susan G. Komen Foundation for the cure, Basser Research Center for BRCA | |

| UPITT/MWH | Frieda G. and Saul F. Shapira BRCA-Associated Cancer Research Program; Hackers for Hope Pittsburgh | |

| VFCTG | Victorian Cancer Agency, Cancer Australia, National Breast Cancer Foundation | Geoffrey Lindeman, Marion Harris, Martin Delatycki of the Victorian Familial Cancer Trials Group. We thank Sarah Sawyer and Rebecca Driessen for assembling this data and Ella Thompson for performing all DNA amplification. |

| WCP | Beth Y. Karlan was supported by the American Cancer Society Early Detection Professorship (SIOP-06-258-06-COUN) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Grant UL1TR000124 |

References

- Abugattas J, Llacuachaqui M, Allende YS, Velásquez AA, Velarde R, Cotrina J, Garcés M, León M, Calderón G, de la Cruz M, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unselected breast cancer patients from Peru. Clin Genet. 2015;88(4):371–5. doi: 10.1111/cge.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ah Mew N, Hamel N, Galvez M, Al-Saffar M, Foulkes WD. Haplotype analysis of a BRCA1: 185delAG mutation in a Chilean family supports its Ashkenazi origins. Clinical Genetics. 2002;62(2):151–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SH, Son BH, Yoon KS, Noh DY, Han W, Kim SW, Lee ES, Park HL, Hong YJ, Choi JJ, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Korean breast cancer patients at high risk of carrying mutations. Cancer Lett. 2007;245(1–2):90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemar B, Herzog J, Brinckmann Oliveira Netto C, Artigalás O, Schwartz IVD, Matzenbacher Bittar C, Ashton-Prolla P, Weitzel JN. Prevalence of Hispanic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients from Brazil reveals differences among Latin American populations. Cancer Genet. 2016;209(9):417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anczukow O, Ware MD, Buisson M, Zetoune AB, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Sinilnikova OM, Mazoyer S. Does the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay mechanism prevent the synthesis of truncated BRCA1, CHK2, and p53 proteins? Hum Mutat. 2008;29(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou AC, Sinilnikova OM, Simard J, Léoné M, Dumont M, Neuhausen SL, Struewing JP, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Barjhoux L, Hughes DJ, et al. RAD51 135G-->C modifies breast cancer risk among BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from a combined analysis of 19 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(6):1186–200. doi: 10.1086/522611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergthorsson JT, Jonasdottir A, Johannesdottir G, Arason A, Egilsson V, Gayther S, Borg A, Hakanson S, Ingvarsson S, Barkardottir RB. Identification of a novel splice-site mutation of the BRCA1 gene in two breast cancer families: screening reveals low frequency in Icelandic breast cancer patients. Human Mutation. 1998;(Suppl 1):S195–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380110163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JL, Teraoka S, Southey MC, Jenkins MA, Andrulis IL, Knight JA, John EM, Lapinski R, Wolitzer AL, Whittemore AS, et al. Population-based estimates of breast cancer risks associated with ATM gene variants c.7271T>G and c.1066-6T>G (IVS10-6T>G) from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(11):1122–8. doi: 10.1002/humu.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu R, Siraj AK, Al-Obaisi KA, Beg S, Al Hazmi M, Ajarim D, Tulbah A, Al-Dayel F, Al-Kuraya KS. Identification of novel BRCA founder mutations in Middle Eastern breast cancer patients using capture and Sanger sequencing analysis. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(5):1091–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1329–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenevix-Trench G, Milne RL, Antoniou AC, Couch FJ, Easton DF, Goldgar DE, CIMBA An international initiative to identify genetic modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA) Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(2):104. doi: 10.1186/bcr1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock-Rada AM, Ossa CA, Garcia HI, Gomez LR. A multi-gene panel study in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Colombia. Fam Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, Garber JE, Neuhausen SL, Matloff E, Eeles R, et al. Association of Risk-Reducing Surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation Carriers With Cancer Risk and Mortality. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(9):967–975. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eachkoti R, Hussain I, Afroze D, Aejazaziz S, Jan M, Shah ZA, Das BC, Siddiqi MA. BRCA1 and TP53 mutation spectrum of breast carcinoma in an ethnic population of Kashmir, an emerging high-risk area. Cancer Lett. 2007;248(2):308–20. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferla R, Calo V, Cascio S, Rinaldi G, Badalamenti G, Carreca I, Surmacz E, Colucci G, Bazan V, Russo A. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 6):vi93–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E, Bar-Sade Bruchim R, Kruglikova A, Risel S, Levy-Lahad E, Halle D, Bar-On E, Gershoni-Baruch R, Dagan E, Kepten I, et al. Double heterozygotes for the Ashkenazi founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(4):1224–7. doi: 10.1086/302040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]