Summary

Ralstonia solanacearum thrives in plant xylem vessels and causes bacterial wilt disease despite the low nutrient content of xylem sap. We found that R. solanacearum manipulates its host to increase nutrients in tomato xylem sap, enabling it to grow better in sap from infected plants than in sap from healthy plants. Untargeted GC/MS metabolomics identified 22 metabolites enriched in R. solanacearum-infected sap. Eight of these could serve as sole carbon or nitrogen sources for R. solanacearum. Putrescine, a polyamine that is not a sole carbon or nitrogen source for R. solanacearum, was enriched 76-fold to 37 μM in R. solanacearum-infected sap. R. solanacearum synthesized putrescine via a SpeC ornithine decarboxylase. A ΔspeC mutant required ≥ 15 μM exogenous putrescine to grow and could not grow alone in xylem even when plants were treated with putrescine. However, co-inoculation with wildtype rescued ΔspeC growth, indicating R. solanacearum produced and exported putrescine to xylem sap. Intriguingly, treating plants with putrescine before inoculation accelerated wilt symptom development and R. solanacearum growth and systemic spread. Xylem putrescine concentration was unchanged in putrescine-treated plants, so the exogenous putrescine likely accelerated disease indirectly by affecting host physiology. These results indicate that putrescine is a pathogen-produced virulence metabolite.

Introduction

Crop pathogens threaten global food security. Among these is Ralstonia solanacearum, which causes bacterial wilt, a high impact plant disease that disrupts the host vascular system. R. solanacearum is globally distributed, infects an expanding host range of over 450 plant species, and is not effectively managed in the field (Elphinstone, 2005). Bacterial wilt inflicts large losses on economically important crops such as tomato, potato, and banana.

R. solanacearum is a soil-borne pathogen that locates its plant hosts by sensing and chemotaxing toward root exudates (Tans-Kersten et al., 2001; Yao and Allen, 2006). R. solanacearum evades root defenses such as nucleic acid extracellular traps (NETs), and enters roots through wounds or natural openings (Vasse et al., 1995; Tran et al., 2016a). The bacterium then systemically colonizes root and stem xylem, a network of metabolically inert tubes that transport water and minerals up from plant roots. In xylem, R. solanacearum forms dense biofilms that restrict sap flow and wilt plants (Vasse et al., 1998; Tran et al., 2016b). R. solanacearum deploys virulence factors such as plant cell wall degrading enzymes, type 3 secreted effectors, and extracellular polysaccharide (Genin and Denny, 2012; Deslandes and Genin, 2014). However, R. solanacearum virulence factors have additive effects, and no single factor completely explains bacterial wilt virulence.

The ability of R. solanacearum to flourish inside the plant xylem is poorly understood. Xylem sap is nutrient poor (Fatima and Senthil-Kumar, 2015); most plant carbon is sequestered intracellularly and transported in the phloem. Metabolites are 10- to 100-fold less concentrated in xylem sap than in the phloem or leaf apoplast (Fatima and Senthil-Kumar, 2015; O'Leary et al., 2016). Xylem is also hypoxic, posing further metabolic constraints for R. solanacearum growth (Dalsing et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the bacterium grows to high cell densities in this niche (Tans-Kersten et al., 2004). One possible explanation for this paradox is that R. solanacearum may alter its xylem habitat by increasing the available nutrients, and/or altering physicial or chemical conditions that limit bacterial growth and spread. Microbial pathogens are known to produce metabolites that manipulate and damage their hosts. For example, the plant pathogens Pseudomonas syringae and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum respectively produce coronatine and oxalate to subvert host plant immunity (Melotto et al., 2006; Kabbage et al., 2015). Human dental pathogens degrade tooth enamel with lactate waste, and trimethylamine produced by choline-utilizing gut bacteria promotes heart disease (Sansone et al., 1993; Romano et al., 2015). Little is known about R. solanacearum metabolites that harm its plant hosts.

To understand how R. solanacearum thrives in the xylem, we used untargeted metabolomics to compare global changes in xylem sap chemistry during bacterial wilt disease of tomato. We found sap from infected plants was enriched in several nutrients that improved R. solanacearum growth in sap. Unexpectedly, our metabolomics analysis also revealed high levels of the polyamine putrescine in sap of wilting plants. R. solanacearum produced the putrescine in xylem sap, but infection also induced expression of several plant putrescine biosynthesis genes in a type 3 secretion system-dependent manner. Furthermore, treating plants with putrescine accelerated bacterial wilt disease progress. Together these results indicate that this polyamine is a virulence metabolite.

Results

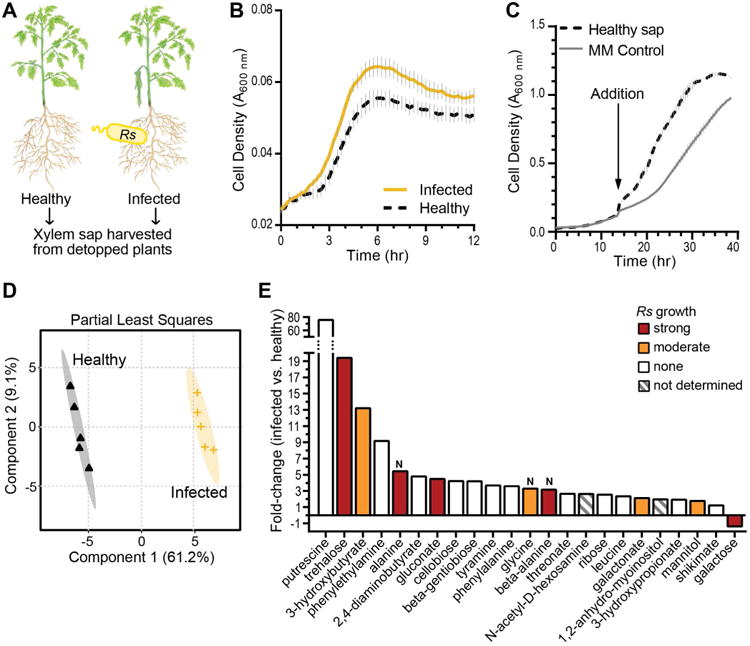

Bacterial wilt disease alters tomato xylem sap to favor R. solanacearum growth

We collected xylem sap from healthy tomato plants and R. solanacearum-infected plants that had developed wilt symptoms within the previous 16 h (Fig. 1A). Unless otherwise noted, hereafter R. solanacearum refers to strain GMI1000. Even at this early stage of disease, sap exudation rate was 1.4-fold slower than in healthy plants, consistent with the model that bacterial wilt disease occludes xylem flow (Fig. S1). We filter-sterilized this ex vivo xylem sap from healthy and infected plants and measured growth of R. solanacearum in these media. Although at this disease stage sap nutrients are continuously depleted by the 109 actively growing R. solanacearum cells in each gram of tomato stem, the sap from two different R. solanacearum-infected tomato cultivars supported more R. solanacearum growth than sap from healthy plants (Fig. 1B). This was true under both aerobic and microaerobic conditions, and five of seven phylogenetically diverse R. solanacearum strains grew better in sap from plants infected by R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 (Fig. S2). We tested the possibility that healthy sap contained concentrated chemicals or defense proteins that inhibited R. solanacearum growth, but supplementing minimal media (MM) with sap from healthy plants improved R. solanacearum growth (Fig. 1C). This suggested that sap from R. solanacearum-infected plants was enriched in nutrients rather than depleted in growth inhibitors. Nonetheless, R. solanacearum growth plateaued by 6 h in the ex vivo sap (Fig. 1B) while the bacterium grows exponentially in planta for over 72 h.

Figure 1. Bacterial wilt disease changes biological and chemical properties of tomato xylem sap.

(A) “Bonny Best” tomato plants were soil-soak inoculated with R. solanacearum GMI1000. At wilt onset, xylem sap was harvested from infected and healthy plants. (B) Growth of R. solanacearum in filtered sap from R. solanacearum-infected and healthy plants. Data are mean ± SEM (n=3). (C) Xylem sap from healthy plants improves R. solanacearum growth in minimal medium (MM). Vacuum-concentrated sap from healthy plants was added to 1× final concentration to actively growing R. solanacearum cultures. Fresh MM was added to the control (AUC = 13.2 ± 0.087). Data are mean ± SEM (n=3). Area under the curve (AUC) for sap treatment (20.4 ± 0.098) and control treatment (13.2 ± 0.087) were significantly different (P<0.001, t-test). (D-E) Relative chemical composition of xylem sap from healthy and R. solanacearum-infected plants was determined by untargeted GC-MS metabolomics (n=5 pools of sap from 4 plants each). (D) Partial least squares analysis of metabolomics data. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence regions (n=5). (E) Xylem sap metabolites altered by bacterial wilt disease, fold-change relative to sap from healthy plants (t-test FDR<0.1); bar colors indicate R. solanacearum growth on each metabolite as sole carbon or nitrogen (“N”) source. Strong and moderate growth are defined in Materials & Methods.

To identify the nutrients that are enriched in xylem sap of R. solanacearum-infected tomato plants, we used untargeted metabolomics to compare the chemical composition of sap from healthy and newly symptomatic R. solanacearum-infected plants. The results revealed that bacterial wilt disease changes the chemical composition of tomato xylem sap (Fig. 1D, 1E, and S3A). GC-MS analysis of sap detected 136 metabolites unmatched to reference database compounds and 118 known compounds, including some previously identified in tomato xylem sap (Dixon and Pegg, 1971; Coplin Sequeira et al., 1974; Zuluaga et al., 2013) (Dataset S1). Overall, nutrients in sap from infected plants were more concentrated; the sap was enriched in 22 known and 17 unknown compounds and depleted in only 1 known and 3 unknown compounds (Fig. 1E). To understand how R. solanacearum grew better in sap from infected plants, we determined which of the altered metabolites served as nutrients (Figs 1E and S4). R. solanacearum grew on trehalose, 3-hydroxybutyrate, alanine, gluconate, β-alanine, galactonate, and mannitol as sole carbon sources, and on alanine, glycine, and β-alanine as sole nitrogen sources. Galactose, the sole compound depleted in infected sap, also supported growth.

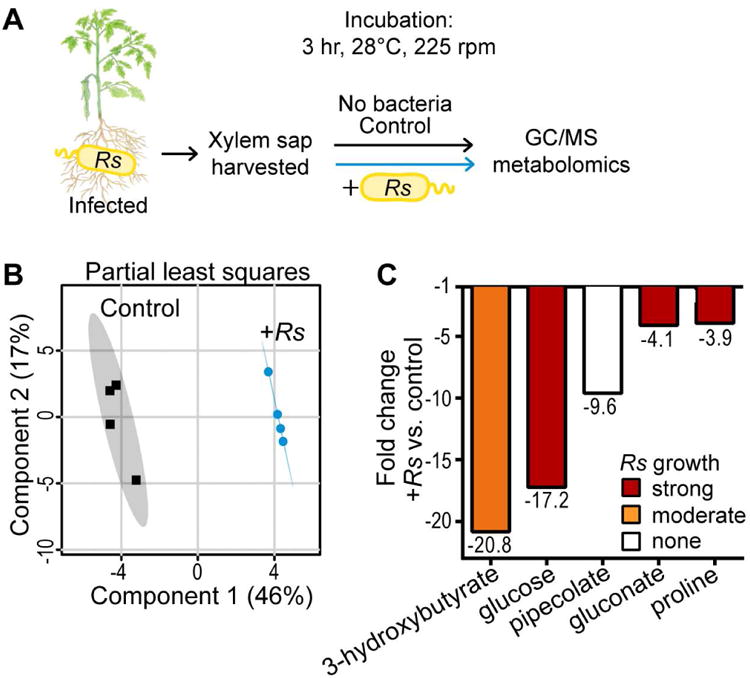

To identify xylem sap metabolites preferentially depleted by R. solanacearum, we analyzed ex vivo sap following 3 h incubation with either R. solanacearum or water (Fig. 2, S3B, and Dataset S1). R. solanacearum growth depleted five compounds: 3-hydroxybutyrate, glucose, pipecolate, gluconate, and proline (Fig. 2C). All depleted compounds supported R. solanacearum growth except pipecolate (Fig. S5). Together these experiments supported the hypothesis that R. solanacearum infection increases available nutrients in plant xylem sap.

Figure 2. Xylem sap metabolites consumed during R. solanacearum GMI1000 growth.

(A) Sap was harvested from infected tomato plants at wilt onset. Pooled sap was incubated with R. solanacearum or water for 3 h before GC-MS metabolomic analysis (n=4 pools of 7 plants each). (B) Partial least squares analysis of sap composition metabolomic data. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence region. (C) Xylem metabolites altered by R. solanacearum growth, fold-change relative to sap incubated without R. solanacearum (t-test, FDR<0.1) Bar color shows R. solanacearum growth on each metabolite as sole carbon or nitrogen (“N”) source.

R. solanacearum produces putrescine in tomato xylem sap and alters tomato polyamine biosynthesis

Not all enriched compounds were nutrients for the bacterium. R. solanacearum could not use the polyamine putrescine as a sole carbon or nitrogen source (Fig. S4), although putrescine was enriched 76-fold in xylem sap from R. solanacearum-infected plants (Fig. 1E). Consistent with this result, the R. solanacearum genome lacks homologs of the characterized putrescine catabolism pathways (Samsonova et al., 2003; Kurihara et al., 2005)

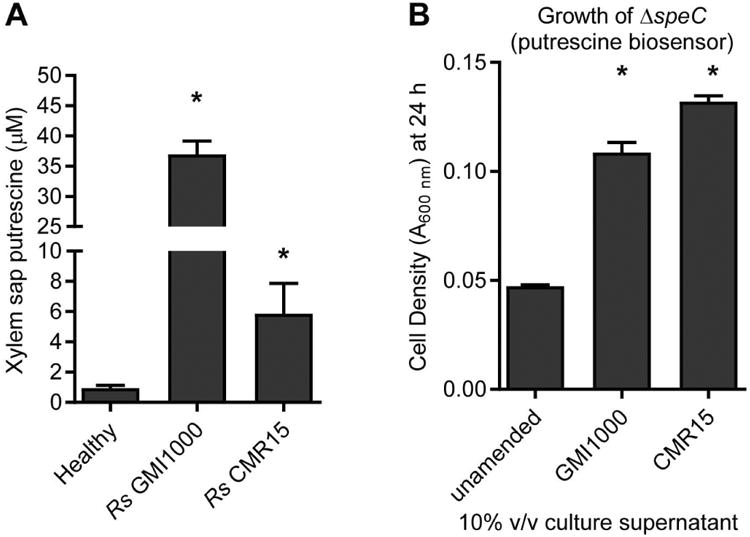

Plants accumulate putrescine and other polyamines during drought (Gupta et al., 2016). Because drought stress and bacterial wilt disease both cause wilting, we investigated whether other wilt pathogens also triggered putrescine accumulation. We quantified putrescine in sap from healthy tomato plants and symptomatic plants inoculated with two R. solanacearum strains and a tomato wilt fungus, Verticillium dahliae (Fig. 3). In sap from healthy plants, putrescine concentration was near the limit of detection (∼1 μM), but infection with R. solanacearum GMI1000 increased sap putrescine levels to 36.9 μM after naturalistic soil-soak inoculation (Fig. 3A). Tomato plants inoculated with GMI1000 through a cut leaf petiole, an artificial inoculation method, accumulated less putrescine (Fig. 4E). Infection with R. solanacearum CMR15 and V. dahliae modestly increased xylem sap putrescine (Figs 3A and S6). Additionally, putrescine accumulated in culture medium of GMI1000 and CMR15 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. R. solanacearum enriches putrescine in xylem sap and culture medium.

(A) Xylem sap was harvested at symptom onset from tomato plants (cv. Money Maker) infected with R. solanacearum strains; water-inoculated plants served as controls. Putrescine was measured by LC-MS. (B) Putrescine in spent culture supernatant was detected by growth of the GMI1000 ΔspeC mutant, a sensitive putrescine biosensor as shown in Figure 4. R. solanacearum strains were grown in minimal medium (MM) for 24 h. Culture supernatants were filter-sterilized and added to fresh MM at 10% v/v and inoculated with ΔspeC. Growth of ΔspeC mutant was measured at 24 h. Values are mean ± SEM. (*P<0.05 vs. healthy, t-test with Holm-Bonferroni correction, n≥3 pools).

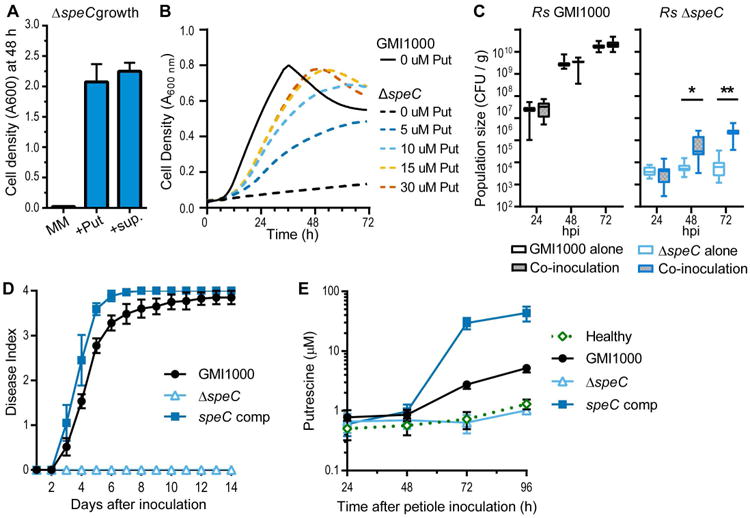

Figure 4. R. solanacearum requires the SpeC ornithine decarboxylase to enrich putrescine in xylem.

(A) Growth of the R. solanacearum ΔspeC mutant in minimal medium (MM), MM plus 100 μM putrescine (+Put), or MM plus 10% v/v filtered R. solanacearum GMI1000 culture supernatant (+sup). Values are mean ± SEM. (n=3). (B) Growth of ΔspeC mutant in MM with 0, 5, 10, 15, or 30 μM putrescine indicates ΔspeC mutant requires at least 15 μM putrescine for maximal growth (n=3). (C) Population sizes of GMI1000-kan and the putrescine biosensor ΔspeC mutant in tomato cv. Money Maker plants after stem inoculation with 103 CFU (alone) or co-inoculation with 103 CFU of each strain (* P<0.05 or ** P<0.0001 t-test, n≥10). (D) Virulence of the ΔspeC mutant on tomato cv. Money Maker plants. Wilt index was measured daily following stem inoculation with 103 CFU (GMI1000 and complemented speC mutant) or 108 CFU (ΔspeC mutant). Values are means ± SEM (n=45). (E) Putrescine concentration in tomato xylem sap measured by LC-MS after stem inoculation with water (healthy), 103 CFU GMI1000, 103 CFU complemented ΔspeC mutant, or 108 CFU ΔspeC mutant. Values are mean ± SEM (n=3-6).

We first investigated whether R. solanacearum GMI1000 produces and exports putrescine in culture and in tomato xylem. Cell pellets of R. solanacearum grown in defined medium contained high levels of putrescine and 2-hydroxyputrescine, trace cadaverine levels, and no detectable spermidine (Fig. S7). This suggested that R. solanacearum produces putrescine, which is consistent with previous findings (Busse and Auling, 1988). All sequenced R. solanacearum genomes encode a predicted putrescine synthesis pathway in which a putative arginine (Arg) decarboxylase (ADC, RSc2365) and an agmatinase (RSp1578) convert Arg to putrescine. However, deletion of RSp1578 did not affect putrescine levels (Fig. S8), showing this gene is not required for putrescine biosynthesis and implying the annotation was incorrect. The RSc2365 decarboxylase that was originally annotated as an ADC belongs to an aspartate aminotransferase-fold family that includes Arg decarboxylases (ADCs), lysine (Lys) decarboxylases, bifunctional Orn/Lys decarboxylases, and ornithine (Orn) decarboxylases (ODCs) (Michael, 2016). ODC enzymes convert Orn to putrescine via decarboxylation. Purified RSc2365 protein had ODC activity but no detectable ADC activity. A substrate competition assay revealed that RSc2365 is a bifunctional Orn/Lys decarboxylase with a strong Orn preference (Fig. S7). Accordingly, we renamed RSc2365 “SpeC” like its ortholog, E. coli SpeC, an Orn/Lys decarboxylase with strong Orn preference (Michael, 2016). Expression of speC is constant in culture and tomato xylem (Jacobs et al., 2012; Khokhani et al., 2017).

To determine how much of the putrescine in xylem sap of infected plants was produced by R. solanacearum, we made an R. solanacearum ΔspeC mutant. The ΔspeC mutant was an auxotroph that could not grow without at least 15 μM exogenous putrescine (Figs 4A and B and Fig. S9), and its growth was poorly complemented by other polyamines (Fig. S9). This suggests that putrescine is essential for R. solanacearum growth even though it cannot be used as a sole carbon or nitrogen source.

The putrescine auxotrophy of the ΔspeC mutant made it a sensitive putrescine biosensor. LC-MS found that xylem sap of R. solanacearum-infected tomato plants contained 36.9 μM putrescine at symptom onset (Fig. 3), so we hypothesized that if tomato plants produced the enriched xylem putrescine, the ΔspeC mutant would be able to grow in planta. However, the ΔspeC mutant did not grow after direct inoculation into the xylem (Figs 4C and S9) and was avirulent even after 108 CFU were directly inoculated into plants (Fig. 4D). At the end of the virulence assay (14 dpi), the speC mutant could not be recovered from tomato stem (limit of detection: 500 CFU/g). The inability of the speC mutant to grow in tomato stem suggested that R. solanacearum, not the tomato plant, produced the putrescine in xylem sap of infected plants. Time-course quantification after cut-petiole inoculation showed that putrescine increased by 72 hpi when GMI1000 populations exceeded 109 CFU /g stem (Fig. 4E), whereas sap from healthy and ΔspeC-infected plants contained no detectable putrescine (∼1 μM limit of detection). These results indicate that wildtype R. solanacearum secretes putrescine in culture and in planta.

Finally, we investigated whether R. solanacearum infection altered putrescine biosynthesis by the tomato plant host. Tomato produces putrescine via two pathways initiated by either ADCs (Sl_ADC1-2) or ODCs (Sl_ODC1-3) (Fig. S10). ADCs and ODCs are rate-determining steps in plant polyamine biosynthesis, and higher ADC and ODC transcription is correlated with increased plant putrescine production (Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014). We measured expression of tomato polyamine biosynthesis genes in roots and stems following inoculation of unwounded roots. In tomato seedling roots, Sl_ADC1, Sl_ODC1, and Sl_SAMDC2 were induced at 24 hpi (Table S1). In stems of symptomatic R. solanacearum-infected tomato plants, Sl_ADC1 expression increased by 4- to 5-fold and Sl_ODC3 expression decreased by 1.9-fold relative to healthy controls (Figs S10B and S10D). To artificially synchronize bacterial wilt disease and track tomato polyamine biosynthesis gene expression over time, we used a cut-petiole inoculation. Under these conditions, Sl_ADC1 expression increased in stem tissue by 48 hpi, when the wildtype R. solanacearum population size exceeded 108 CFU/g stem (Figs S10C-D). Although this induction of Sl_ADC1 coincided with the increase in xylem sap putrescine concentration in wildtype-infected plants (Figs S10D and 4E), Sl_ADC1 was similarly induced in tomato stem tissue carrying an equal bacterial load of the ΔspeC mutant (Figs S10C and S10E). Under this condition, putrescine does not accumulate in xylem sap (Fig. 4E). Intriguingly, Sl_ADC1 was not induced in tomato plants infected with a ΔhrcC mutant, which lacks type 3 secretion (Fig. S10E).

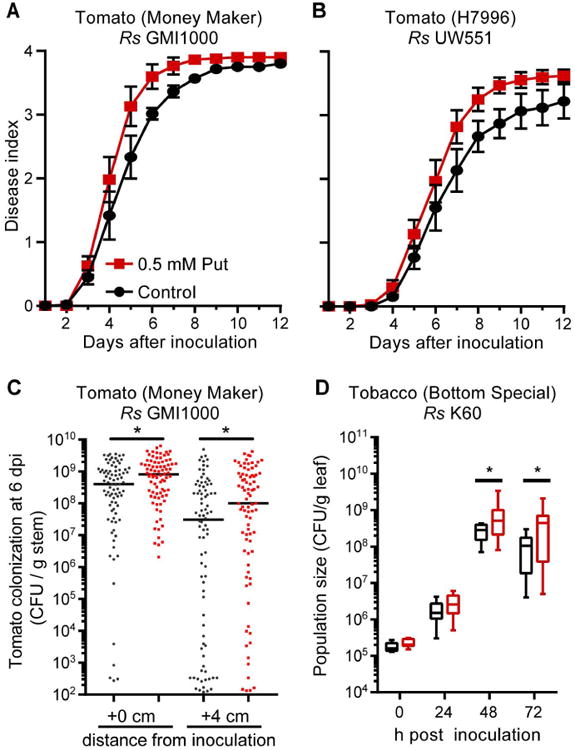

Exogenous putrescine accelerates bacterial wilt disease development

Polyamines have pleiotropic effects on plant physiology (Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2016). To test the hypothesis that putrescine affects disease development, we treated tomato plant soil and leaves with 0.5 mM putrescine or water 3 h before stem inoculation with R. solanacearum. Putrescine treatment accelerated bacterial wilt disease on two susceptible tomato cultivars (Fig. 5A and S11) although the concentration of putrescine in xylem sap did not increase (Fig. S11). Putrescine treatment also accelerated symptom development on quantitatively wilt-resistant tomato line H7996 inoculated with resistance-breaking R. solanacearum strain UW551 (Fig. 5B). However, putrescine did not break the resistance of H7996 to R. solanacearum GMI1000 (Fig. S11). Stomatal conductance and sap exudation rates were both reduced in symptomatic infected plants, but putrescine treatment did not affect these physiological behaviors (Figs S1 and S11).

Figure 5. Exogenous putrescine accelerated bacterial wilt disease.

Putrescine (0.5 mM in water) was applied to roots and leaves of plants 3 h before inoculation with R. solanacearum via (A-C) stem inoculation or (D) leaf infiltration. (A and B) Effect of putrescine on wilt symptom development after stem inoculation of (A) susceptible tomato with 50 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000 (P=0.0183, repeated measures ANOVA; values are mean ± SEM; n=60 plants/treatment) or (B) quantitatively resistant tomato with 5,000 CFU R. solanacearum resistance-breaking strain UW551 (P=0.0403, repeated measures ANOVA; Values are mean ± SEM; n=60 plants/treatment). Effect of putrescine on R. solanacearum (C) growth and spread in tomato stem after stem inoculation of putrescine-treated (red) or control (black) plants, (*P<0.05 Mann-Whitney test, n>80 plants/treatment) and (D) growth in tobacco leaf apoplast after putrescine (red) or water (black) treatment (*P<0.05 t-test; n>12 plants/treatment).

Putrescine treatment accelerated wilt by increasing bacterial growth and spread in the xylem. At 6 dpi, R. solanacearum population sizes in putrescine-treated plants were 3.8-fold larger at the site of inoculation and 8-fold larger four cm above the inoculation site, as compared to control plants treated with water (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the accelerated bacterial growth, putrescine treatment increased expression of tomato PR1b and ACO5, which are markers for the plant salicylic acid and ethylene defense signaling pathways (Fig. S12). PR1b and ACO5 are also induced by R. solanacearum infection (Milling et al., 2011) Moreover, putrescine treatment of tobacco plants increased growth of tobacco pathogenic R. solanacearum strain K60 in leaf apoplast (Fig. 5D). Because treating plants with exogenous putrescine did not increase putrescine levels in in xylem sap (Fig. S11), putrescine treatment must alter tomato physiology in a way that increases R. solanacearum growth in the xylem.

Discussion

Bacterial wilt disease increases xylem sap nutrients

Most previous characterizations of tomato xylem sap used healthy plants (Coplin Sequeira et al., 1974; Chellemi et al., 1998; Zuluaga et al., 2013). It has long been known that xylem sap contains organic acids, amino acids, and inorganic ions (nitrate, iron, and sulfate), and sucrose was recently detected (Jacobs et al., 2012; Dalsing et al., 2015). The fungal wilt pathogen V. albo-atrum enriches amino acids in tomato xylem (Dixon and Pegg, 1971), but data on the effects of R. solanacearum infection on xylem sap are limited and inconsistent (Coplin Sequeira et al., 1974; McGarvey et al., 1999). Although differing methods make direct comparisons across studies difficult, these data, together with our observation that R. solanacearum grows better in ex vivo xylem sap from infected plants, strongly suggest that R. solanacearum infection significantly alters this key habitat in ways that favor the pathogen.

We found R. solanacearum grows better on xylem sap from infected plants than sap from healthy plants, probably because sap from diseased plants is enriched in at least three nitrogen and seven carbon sources. Although R. solanacearum can synthesize many of these nutrients, the rapid growth of the pathogen in xylem suggests they come from the host. Furthermore, the 22 enriched metabolites may not be the complete set of enriched metabolites because this list excludes metabolites R. solanacearum consumed at the same rate as they entered the xylem. Consistent with this idea, R. solanacearum depleted two non-enriched nutrients (glucose and proline) in ex vivo sap within 3 h.

Amino acids and other organic nitrogen compounds are likely important nitrogen sources for R. solanacearum in the xylem. Tomato xylem sap contains ∼ 1 mM total amino acids and 40 mM nitrate (Dixon and Pegg, 1971; Zuluaga et al., 2013; Dalsing et al., 2015). In the oxygen-limited xylem, R. solanacearum uses nitrate primarily as an alternate electron acceptor (Dalsing et al., 2015). Our study suggests the key nitrogen sources fueling bacterial growth in the xylem are alanine, β-alanine, glycine, and proline.

We identified galactose, 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB), gluconate, and glucose as important carbon sources for R. solanacearum in the xylem. Galactose was the only xylem metabolite depleted by bacterial wilt disease. Interestingly, quorum sensing regulates R. solanacearum galactose catabolism such that galactose is only metabolized by R. solanacearum at high cell densities, corresponding to successful xylem colonization (Khokhani et al., 2017). 3HB is precursor of the carbon storage molecule polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), which bacteria often produce when carbon is in excess and redox is constrained (Terpolilli et al., 2016). Microscopy and transcriptomic data suggest PHB metabolism is active when R. solanacearum grows in the xylem (Grimault et al., 1994; Brown and Allen, 2004; Jacobs et al., 2012). 3HB was both enriched in infected sap and depleted after R. solanacearum grew in ex vivo sap. R. solanacearum may produce and secrete 3HB to sequester carbon in a form unavailable to the host during early disease. Then at a late disease stage, when glucose may be limited, R. solanacearum may import and polymerize 3HB into PHB to store carbon for survival outside the host. Although plant metabolism could theoretically account for the observed decrease in galactose, tomato plants are an unlikely source for the enriched 3-hydroxybutyrate because the tomato genome does not encode homologs of 3-hydroxybutyrate metabolism and are not known to carry out 3-hydroxybutyrate metabolism (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000).

Although the 1.6-fold glucose enrichment in sap from infected plants was non-significant, R. solanacearum preferentially consumed glucose in ex vivo sap. This suggests glucose is consumed by R. solanacearum at the same rate as it enters the xylem. Consistent with this idea, R. solanacearum glycolysis genes are highly expressed in planta (Brown and Allen, 2004; Jacobs et al., 2012; Khokhani et al., 2017). Our untargeted metabolomic analysis generated relative concentration data. Follow-up studies are needed to determine absolute quantities of nutrients in xylem sap from healthy and diseased plants and to quantify metabolic flux as R. solanacearum consumes xylem sap nutrients. These results could refine the existing metabolic model to provide a more biologically complete picture of R. solanacearum metabolism in the host (Peyraud et al., 2016).

Xylem vessels are not static. Sap flows through vessels to transport water and minerals to foliar tissue. As in a chemostat, xylem sap continuously supplies nutrients to and removes waste from R. solanacearum biofilms. Furthermore, the xylem is a heterogeneous environment, so pooling xylem sap obscures aspects of its chemical ecology. Nutrients are likely more concentrated at the bordered pits that connect the inert xylem vessels to adjacent metabolically active cells, which is consistent with microscopy showing R. solanacearum cells clustered at pits (Grimault et al., 1994; Nakaho et al., 2000). Bacterial consumption and metabolite diffusion within R. solanacearum biofilms likely creates a nutrient availability gradient that could support metabolically heterogenous populations. This spatial heterogeneity could be defined with bacterial biosensors.

What mechanisms cause metabolite enrichment in xylem?

How might plants load nutrients like glucose into xylem during bacterial wilt disease? R. solanacearum cell wall-degrading enzymes release cellulose-derived metabolites like cellobiose and gentiobiose (Genin and Denny, 2012). Cellulases and pectinases are known bacterial wilt virulence factors, but their exact mechanisms of action are unknown (Genin and Denny, 2012). Cell wall breakdown could directly release sugars or facilitate leakage of metabolites into the xylem from adjacent tissue.

R. solanacearum may enrich host sap by subverting plant nutrient transport. For example, xylem embolisms formed during bacterial wilt disease could increase nutrients via phloem unloading. The intriguing but unproven phloem unloading hypothesis proposes that plants restore embolisms by moving phloem sugars into the xylem; this solute influx restores sap flow by drawing water into the vessel until the embolizing air is displaced or dissolved (Brodersen et al., 2010; Nardini et al., 2011). If plants use this mechanism to restore xylem function, it would be surprising if xylem pathogens did not manipulate it.

Finally, R. solanacearum may use its type 3 secretion system to manipulate the host to load nutrients into the xylem (Deslandes and Genin, 2014). Plant pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. use type 3 secreted transcriptional activator-like effectors (TALEs) that induce expression of host SWEET-family sucrose transporter genes (Streubel et al., 2013). These TALEs increase host susceptibility, presumably by raising sucrose levels. R. solanacearum GMI1000 has over 70 type 3 effectors, including a TALE that targets an unknown host gene (de Lange et al., 2013; Deslandes and Genin, 2014). It has long been assumed that R. solanacearum injects effectors into the living xylem parenchyma cells that are connected to vessels by bordered pits. Recent work confirmed this by visualizing delivery of an R. solanacearum effector (PopP2) into living Arabidopsis cells surrounding the xylem in petioles (Henry et al., 2017).

What is the source of the enriched putrescine during bacterial wilt disease?

The polyamine putrescine was strikingly enriched in xylem sap from tomato plants infected with R. solanacearum. Several lines of evidence indicate R. solanacearum produced this putrescine: 1) Mutant and biochemical analyses showed R. solanacearum synthesizes putrescine via the SpeC ornithine decarboxylase; 2) LC-MS showed R. solanacearum exports putrescine; 3) Co-inoculation with wildtype R. solanacearum partially rescued in planta growth of a ΔspeC mutant; 4) Plant putrescine synthesis could not rescue the ΔspeC mutant's auxotrophy, even though Sl_ADC1 was induced by ΔspeC infection.

R. solanacearum secretes putrescine, but the mechanism of putrescine export is unexplored. Because polyamines are positively charged at physiological pH, they require active transport across membranes. R. solanacearum has homologs of the PotABCD polyamine importer (Igarashi and Kashiwagi, 2010), which likely allowed exogenous putrescine to rescue ΔspeC growth. The R. solanacearum genome does not encode homologs of known polyamine exporters (Igarashi and Kashiwagi, 2010; Sugiyama et al., 2016), suggesting R. solanacearum uses a novel transport system.

The ΔspeC strain proved to be a sensitive putrescine biosensor. In planta growth of ΔspeC increased by 48 hpi when co-inoculated with wildtype R. solanacearum, but LC-MS did not detect increased putrescine until 72 hpi. ΔspeC cells nestled in biofilm with putrescine-exporting wildtype cells likely benefited from locally high putrescine levels that were diluted in exuded sap.

Our results raise compelling questions: 1) Do living plant cells import the R. solanacearum-produced putrescine? Putrescine uptake by plant cells or putrescine dilution by xylem flow could explain why we detected ten-fold less putrescine in sap of wildtype-infected plants than in culture supernatant containing similar bacterial populations. 2) Does R. solanacearum directly increase tomato putrescine synthesis? We observed that induction of Sl_ADC1 by R. solanacearum infection required a functional T3SS, which suggests that one or more R. solanacearum T3 effectors target host polyamine synthesis. This hypothesis is consistent with bioinformatic predictions that RipTAL-1 targets host genes involved in biosynthesis of polyamines (T. Lahaye, unpublished). Targeting host polyamine metabolism is a virulence strategy for X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv) and Heterodera cyst nematodes (Hewezi et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2013). Both pathogens deploy effectors that interact with plant polyamine biosynthesis enzymes: Xcv AvrBsT targets pepper ADC1 and Heterodera effector 10A06 increases activity of an Arabidopsis spermidine synthase (SPDS2). However the mechanism whereby polyamines promote virulence remains unclear for these pathosystems.

Why does putrescine accelerate bacterial wilt disease?

Polyamines influence virulence traits of many bacteria (reviewed in Di Martino et al., 2013). Polyamines are essential for biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis and induce type 3 secretion gene expression and function in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Patel et al., 2006; Jelsback et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2007). Polyamines protect bacteria against many membrane stresses, including oxidative damage and cationic peptides like polymyxin B and the histones of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (El-Halfaway et al. 2014; Goytia et al., 2010; Halverson et al., 2015). Putrescine enrichment in xylem sap may affect R. solanacearum biofilm, type 3 secretion, and resistance to host ROS. However, exogenous application of putrescine to roots and leaves accelerated bacterial wilt disease without detectably increasing putrescine concentration in xylem sap. This suggests that putrescine directly increases host plant susceptibility to R. solanacearum.

Putrescine and other polyamines play pivotal and pleiotropic roles in plant biology. Polyamines stabilize membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids; regulate plant growth; moderate drought stress; and participate in varied interactions with microbes (Marina et al., 2008; Hewezi et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2013; Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2016). Polyamines sometimes benefit pathogens and sometimes boost plant immunity (Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014). It has been observed that “In plant-pathogen interactions, the organism that takes control of polyamine metabolism has the advantage” (Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014). Although the specific roles of polyamines in plant-microbe interactions are uncertain, there are hints. When polyamines contribute to plant defense, it is often because their catabolism releases the plant defense signal H2O2 (Marina et al., 2008; Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2016). Although R. solanacearum induces putrescine catabolism in a resistant host (Aribaud et al., 2010), we found that the activity of the putrescine catabolism enzyme diamine oxidase was 2.3-fold repressed in R. solanacearum-infected vs. healthy tomato plants. Conversely, polyamines can also reduce H2O2 levels directly as antioxidants and indirectly by increasing host catalase activity (Gupta et al., 2016). It would be interesting to determine if putrescine dampens the oxidative defense response of susceptible tomato plants (Milling et al., 2011).

Why does R. solanacearum increase putrescine levels in host xylem?

Most free-living organisms make polyamines, usually putrescine and spermidine. Like other β-proteobacteria R. solanacearum produces putrescine and 2-hydroxyputrescine (Li et al., 2016). R. solanacearum cell lysates lack spermidine, although the R. solanacearum GMI1000 genome encodes three spermidine synthase-like proteins that are not typical homologues of known spermidine synthases (Michael, 2016). R. solanacearum is the first example of a bacterium that does not produce spermidine but absolutely requires putrescine (Hanfrey et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2016; Michael, 2016). R. solanacearum requires putrescine for growth, but our results suggest that R. solanacearum-produced putrescine also affects the plant host. There are precedents: for example, putrescine secreted by the eukaryotic pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis triggers host cell death (Garcia et al., 2005).

Is putrescine a virulence metabolite?

Independent lines of evidence suggest the abundant R. solanacearum-produced putrescine increases bacterial wilt virulence. R. solanacearum manipulated expression of host putrescine biosynthetic genes via its type 3 secretion system, suggesting polyamine levels are important during bacterial wilt disease (Hewezi et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2013). Treating plants with exogenous putrescine accelerated bacterial wilt disease on three tomato genotypes, and exogenous putrescine increased bacterial spread and growth in tomato and tobacco plants responding to phylogenetically divergent R. solanacearum strains. R. solanacearum cannot use putrescine as either a sole carbon or nitrogen source, so putrescine does not improve the bacterium's growth directly by acting as a nutrient. We wondered if exogenous putrescine directly or indirectly upregulates twitching motility or biofilm formation, known R. solanacearum virulence factors that are responsive to polyamines in other bacteria (Patel et al., 2006; Skiebe et al., 2012; Di Martino et al., 2013). However, exposing R. solanacearum to physiological levels of putrescine did not affect these traits (Fig. S11G). Further, it is unlikely that exogenous putrescine directly affected the xylem-dwelling R. solanacearum cells because putrescine treatment did not increase xylem sap putrescine levels, as indicated by either direct LC-MS measurements or by the sensitive ΔspeC biosensor strain. We therefore favor the hypothesis that pathogen-produced putrescine contributes to virulence by acting on host plant physiology, possibly by reducing reactive oxygen species.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial and fungal strains and routine culturing conditions

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. R. solanacearum strains were grown at 28°C on CPG medium (1 g L-1 casamino acids, 10 g L-1 peptone, 5 g L-1 glucose, and 1 g L-1 yeast extract). Antibiotics were added to media: 20 mg L-1 spectinomycin, 5 mg L-1 tetracycline, and 25 mg L-1 kanamycin. E. coli were grown on LB medium at 37 °C. The ΔspeC mutant was grown on CPG broth amended with 100 μM putrescine or on solid CPG amended with 1 mM putrescine. Boucher's minimal medium (MM) pH 7.0 containing 20 mM glucose, 3.4 g L-1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g L-1 (NH4)2SO4, 0.125 mg L-1 FeSO4-7H2O, and 62.3 mg L-1 MgSO4 was used for experiments requiring defined minimal medium. Verticillium dahliae JR2 was grown on potato dextrose agar.

R. solanacearum growth on metabolites present in xylem sap

To assess carbon and nitrogen source utilization, R. solanacearum GMI1000 was grown in MM with 10 mM test compounds. MM was prepared as described above without glucose for sole carbon source experiments or without (NH4)2SO4 for sole nitrogen source experiments. Overnight cultures were washed and inoculated into 200 μl MM containing test substrates to a density of OD600 = 0.05 in a 96-well flat-bottomed microplate (Corning). Kinetic growth data was collected in a Synergy HTX plate reader with shaking at 28°C and A600 nm measurements recorded every 30 min for 72 h. Relative growth on the metabolites was determined by calculating the mean area under the growth curve (AUC) of three biological replicates. Carbon or nitrogen sources that yielded AUCs of >17, ≥4, or <4 were assigned into strong, moderate or no growth categories, respectively. Generally, moderate and strong growth indicates R. solanacearum culture grew from A600 = 0.03 to a maximum A600 nm of 0.33-0.511 and 0.584-1.145, respectively.

Strain construction

Gene replacement and complementation constructs were created by Gibson assembly (Gibson et al., 2009) (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA). The ΔspeC mutant was created by allelic replacement of the speC gene (RSc2365) with the Ω cassette carrying a spectinomycin resistance marker. The 1,077 bp region directly upstream of RSc2365, the Ω cassette from pCR8, and the 903 bp region directly downstream of RSc2365 were assembled into the HindIII site of pST-Blue. These PCR products were generated with primer sets RSc2365upF/R, omega(c2365)F/R, and RSc2365dwnF/R, respectively (Table S2). R. solanacearum GMI1000 was transformed with SspI-linearized pKO-speC∷Sm by electroporation and transformants were selected with spectinomycin. After initial attempts to select for speC deletion were unsuccessful, we added 1 mM putrescine to selection medium, and obtained a ΔspeC mutant that was confirmed by PCR genotyping. The speC complementation vector pRCT-speC_com was created by Gibson assembly. The 2.7 kb fragment containing the predicted native promoter and the monocistronic speC gene was amplified with the primers speC_comF/R (Table S2) and fused into the XbaI/KpnI site of pRCT-GWY (Monteiro et al., 2012). R. solanacearum GMI1000 was transformed with pRCT-speC_com by electroporation, transformants were selected with tetracycline, and strains were confirmed by PCR screening.

The unmarked ΔhrcC mutant was produced using pUFR80-hrcC, a derivative of a sacB positive selection vector (Castañeda et al., 2005). Regions upstream and downstream of the RSp0874 hrcC gene were amplified using hrcCupF/R and hrcCdwnF/R (Table S2). GMI1000 was transformed with pUFR80-hrcC, and plasmid integration was selected with kanamycin medium. Plasmid loss was counter-selected from a KanR clone on 5% w/v sucrose, yielding a mixture of wildtype and ΔhrcC mutant genotype colonies. PCR screening identified a ΔhrcC mutant. The ΔhrcC mutant was phenotypically screened for absence of type 3 secretion activity using a tobacco hypersensitive response assay (Poueymiro et al., 2009).

The unmarked ΔRSp1578 mutant was produced using pUFR80-RSp1578. The regions upstream and downstream of RSp1578 were amplified using 1578upF/R and 1578dwnF/R (Table S2). R. solanacearum GMI1000 was transformed with pUFR80-RSp1578, and ΔRSp1578 mutants were selected as described for the ΔhrcC mutant.

Characterizing growth requirements of ΔspeC mutant

To determine which polyamines and structurally related molecules compensated for the putrescine auxotrophy of the ΔspeC mutant, the mutant was grown in MM amended with test substrates. Some growth of the ΔspeC mutant occurred in unamended MM if 100 μM putrescine was added to the parent overnight ΔspeC cultures (Fig. S9). To deplete intracellular putrescine stores in ΔspeC cells before growth experiments, subsequent experiments were conducted with ΔspeC cells from overnight cultures in unamended CPG, which contains only trace polyamines that supported limited growth of the mutant. Overnight cultures were washed and resuspended to OD600 = 0.05 in 200 μl MM amended with 0, 50, 100, 500 μM, or 1 mM putrescine, spermidine, cadaverine, or agmatine in a 96-well flat-bottomed microplate (Corning). Growth was recorded every 30 min as A600 for 48 h in a Synergy HTX plate reader.

To determine whether diverse R. solanacearum isolates excreted putrescine to culture supernatant, strains were grown for 24 h in MM to OD600 =1.25. Bacteria were pelleted, and supernatant was sterilized through a 0.22 μm filter. Culture supernatant was added to MM at 10% v/v final concentration, and 5 ml aliquots were inoculated with ΔspeC cells (OD600=0.005) that had been putrescine-depleted as described above. Growth was compared to growth in unamended MM (negative control) and MM with 100 μM putrescine (positive control).

Plant growth conditions

Tomato seeds (wilt-susceptible cvs. Bonny Best and Money Maker, and quantitatively wilt-resistant breeding line Hawaii 7996) and tobacco cv. Bottom Special were sown in professional growing mix soil (Sunshine Redimix, Glendale, AZ) in a 28°C climate chamber with a 12 h photoperiod cycle. Tomato seedlings were transplanted 14 d post-sowing into individual 4-inch pots containing ∼80 g soil. Tobacco plants were transplanted after foliage diameter exceeded 1 cm. Transplants were watered with 50% Hoagland's solution.

Tomato and tobacco inoculation with R. solanacearum

Two methods were used to inoculate tomato plants: a naturalistic soil-soaking method and a stem inoculation method that directly introduces R. solanacearum into the xylem (Tans-Kersten et al., 2001). Plants were inoculated 17-21 d after sowing. For the soil soaking method, a suspension of R. solanacearum was poured into soil to a final concentration of 5×108 CFU g-1 soil (50 ml of OD600=0.2). For cut-petiole stem inoculations, 2 μl of a bacterial suspension was placed on the stump of a freshly removed leaf petiole. Inocula ranged from 5×101 to 1×108 total CFU depending on experiment and bacterial genotype. Tobacco plants were inoculated by leaf infiltration: a 105 CFU / ml water suspension of R. solanacearum K60 was infiltrated into fully expanded leaves with a needleless syringe. For co-inoculation experiments, kanamycin-marked GMI1000 and the spectinomycin-marked ΔspeC mutant were introduced at equal concentration. Overnight cultures of each strain were resuspended to OD6oo of 0.2, mixed 1:1, and diluted to 5×105 CFU ml-1 each of GMI1000 and ΔspeC mutant to deliver 103 CFU of each strain(Yao and Allen, 2006). All inoculum concentrations were confirmed with dilution plating.

R. solanacearum disease and colonization assays

For disease assays, symptoms were measured daily using a 0-4 disease index scale (Tans-Kersten et al., 2004): 0: asymptomatic; 1: up to 25% leaflets wilted; 2: up to 50% leaflets wilted; 3: up to 75% leaflets wilted; and 4: up to 100% leaflets wilted. Disease progress experiments were conducted at least three times with 10-15 plants per condition.

Bacterial population sizes in planta were determined by homogenizing 100 mg tomato stem or 1 cm2 tobacco leaf (∼33 mg) in a bead-based Powerlyzer homogenizer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Samples were ground at room temperature in 1 ml sterile water with four 2.38 mm metal beads for two cycles of 2200 rpm for 1.5 min with a 4 min rest between cycles. Homogenate was dilution plated in triplicate on appropriate media, and colonies were counted after 2 d incubation at 28°C. To measure R. solanacearum population and spread after putrescine treatment, 50 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000 was cut-petiole inoculated into 26 d-old tomato plants, which have longer stems than 21 d-old plants. After 6 d, bacterial populations were enumerated at the site of inoculation and 4 cm above.

Xylem sap harvest

Xylem sap was harvested from plants 1-3 h after onset of daylight to control for diurnal changes in sap composition (Siebrecht et al., 2003). To ensure adequate water status, plants were watered each evening before morning sampling. Plants inoculated by soil soaking were detopped 2 cm above the cotyledons, and plants inoculated by petiole inoculation were detopped at the site of inoculation. Root pressure forced xylem sap to accumulate on the stump. The sap accumulated after the first 2-3 min was discarded, and the stump was washed with water and gently blotted dry as previous described (Goodger et al., 2005). For the next 20-30 min the sap was frequently transferred into pre-chilled tubes in a -20 °C block or on ice. Samples were flash-frozen and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Population sizes in stems were determined as described above.

Bacterial growth in ex vivo xylem sap

Ex vivo xylem sap was harvested as described above. Xylem sap was pooled from at least 3 plants and sterilized through a 0.22 μm filter. Overnight cultures were washed three times, and bacteria were inoculated into 50 μl xylem sap to a final density of OD600=0.1 in a half-area 96-well microplate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), corresponding to A600≈0.03 in the microplate wells. Kinetic growth data was collected in a Synergy HTX plate reader with 28°C incubation and variable shaking (BioTek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT). Microaerobic growth experiments were performed as described (Dalsing et al., 2015). Briefly, the experiments were performed in a plate reader housed in an environment-controlled chamber at 0.1% oxygen and 99.9% N2 gas.

To determine whether xylem sap from healthy tomato plants inhibited R. solanacearum growth, xylem sap from healthy plants was concentrated 2-fold in a Speed-Vac and added to an equal volume of R. solanacearum growing in MM. Overnight cultures were washed and resuspended to OD600 = 0.1 in MM before transferring to a 96-half-area-well microplate (50 μl per well). After 14 h growth, 50 μl of two-fold concentrated xylem sap was added to the actively growing cultures, yielding a final concentration of 1× xylem sap. Fresh MM (50 μl) was added to control wells. The plate was returned to the plate reader and A600 nm was measured for an additional 24 h.

The lack of growth inhibition of healthy xylem sap was confirmed on solid media using an overlay inhibition assay (Huerta et al., 2015). Briefly, a suspension of R. solanacearum cells in semi-solid CPG agar was overlaid on solid CPG agar. Wells were excised from the solidified plates with a hole punch. Water, non-concentrated xylem sap, or ten-fold concentrated xylem sap (concentrated in a vacuum concentrator) was added to the wells, and bacterial growth was observed after 48 h incubation at 28 °C. The xylem sap did not induce a zone of inhibition, even when added at ten-fold concentration.

GC-MS metabolomics of xylem sap

Sap from soil-soak inoculated plants was used for the untargeted metabolomics experiments. The first experiment compared sap from healthy tomato cv. Bonny Best plants to sap from symptomatic plants infected with R. solanacearum GMI1000. To minimize variation, several guidelines were followed when selecting samples for analysis. Although soil-soak inoculations result in asynchronous infections, infected plants showing the first wilt symptoms (<25% leaflets wilted) consistently harbored bacterial populations of ∼1×109 CFU g-1 stem. Infected plants displaying the first wilt symptoms (6-10 dpi) and an equal number of healthy plants were selected each day. To ensure that infected plants were at a similar disease state, plants that developed first symptoms during the afternoon were discarded; xylem sap was only sampled from plants that developed wilt symptoms overnight. Additionally, all infected samples came from plants with bacterial density between 1×109-1×1010 CFU per g stem. To avoid distortion of metabolite concentrations due to differential flow rates, only samples with a median sap volume (250-350 μl) were chosen for pooling from the 103 infected and the 69 healthy samples collected. Pools were composed of samples collected across the sampling time. To yield 0.5 to 1 ml, equal volumes of sap from 4 samples were pooled for each of 5 biological replicates. For pooling, samples were thawed on ice, and debris was removed from samples by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 3 min at 4°C. Mean exudation rate of healthy pools was 0.975 ml min-1, and mean exudation rate of R. solanacearum-infected pools was 0.613 ml min-1 (Fig. S1).

The second untargeted metabolomics experiment compared xylem sap from infected plants after incubation with or without R. solanacearum GMI1000 for 3 h. Xylem sap was harvested from infected plants as described above. Samples with a median sap volume (150-390 μl) were chosen for pooling from the 134 samples harvested. Each pool was produced from 14 samples. Samples were thawed on ice and sterilized with 0.22 μM filters. Each pool was divided; half was inoculated with a water suspension of R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 to OD600 nm = 0.1, and half of the pool received an equal volume of water. Samples were incubated at 28°C with shaking for 3 h. Bacteria were pelleted, and the supernatant was transferred to fresh tubes, flash frozen, and stored at -80 °C until samples were shipped on dry ice for metabolomics analysis.

GC-MS analysis was performed by West Coast Metabolomics (Univ. California, Davis). Xylem sap (500 μl) was extracted with 1 ml of ice cold 5:2:2 MeOH:CHCl3:H2O. The upper phase was transferred into a new tube and a 500 μl aliquot was dried under vacuum. The residue was derivatized in a final volume of 100 μl. Detailed methods of metabolite derivatization, separation, and detection are described (Fiehn et al., 2005). Briefly, samples were injected (0.5 μl, splitless injection) into a Pegasus IV GC (Leco Corp., St Joseph, MI) equipped with a 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. fused-silica capillary column bound with 0.25 μm Rtx-5Sil MS stationary phase (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA). The injector temperature was 50°C ramped to 250°C by 12°C s-1. A helium mobile phase was applied at a flow rate of 1 ml min-1. Column temperature was 50°C for 1 min, ramped to 330°C by 20°C min-1 and held constant for 5 min. The column effluent was introduced into the ion source of a Pegasus IV TOF MS (Leco Corp., St Joseph, MI) with transfer line temperature set to 230°C and ion source set to 250°C. Ions were generated with a -70 eV and 1800 V ionization energy. Masses (80-500 m/z) were acquired at a rate of 17 spectra s-1. ChromaTOF 2.32 software (Leco Corp) was used for automatic peak detection and deconvolution using a 3 s peak width. Peaks with signal/noise below 5:1 were rejected. Metabolites were quantified by peak height for the quantification ion. Metabolites were annotated with the BinBase 2.0 algorithm (Skogerson et al., 2011).

Statistical analyses were conducted in MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (Xia et al., 2015). Although pooled samples were selected from plants with median sap exudation rates, the exudation rate of plants in the healthy pools was 1.2-fold greater than that of plants in the infected pools. Because exudation rate alters sap metabolite concentration (Goodger et al., 2005), we normalized metabolite peak heights by mean exudation rate for each pooled sample. Multivariate and univariate statistics were performed on generalized log transformed peak heights. Metabolites with FDR <0.1 were considered differentially concentrated.

Targeted analysis of putrescine in xylem sap

Putrescine was quantified in tomato cv. Money Maker xylem sap from plants infected with R. solanacearum and V. dahliae JR2. Plants were inoculated with R. solanacearum by soil-soak inoculation and sap was harvested as described above. Three pools of sap from 3 plants each were lyophilized before analysis. Plants were inoculated with the wilt fungus V. dahliae as previously described (Fradin et al., 2009). Briefly, 10 d-old tomato plants were uprooted, rinsed briefly in water, and submerged in a V. dahliae spore suspension at a concentration of 106 conidia ml-1. The spore suspension was prepared from one- to two-week-old V. dahliae plates grown on potato dextrose agar and suspended in 20% potato dextrose broth. Following inoculation, plants were potted in metro mix and grown in the greenhouse. At 9 dpi, xylem sap was sampled from healthy and symptomatic V. dahliae-infected plants as described above. Three pools of sap from 5 plants each were lyophilized before analysis.

LC-MS separation and detection of putrescine was performed as reported (Sánchez-López et al., 2009) using an Ekspert Micro-LC 200 and a QTRAP4000 (ABSciex, Framingham, MA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a 150 × 0.5 mm HaloFused C18 column with particle size 2.7 μm (AB Sciex) and column temperature 35°C. A binary gradient at a flow rate of 11 μl min-1 was applied: 0-0.5 min isocratic 90% A; 0.5-4 min, linear from 90% A to 1% A; 4-4.8 min, isocratic 1% A; 4.8-5 min, linear from 1% A to 90% A; 5-5.5 min, linear to 99% A, 5.5-5.8 min, linear to 90% A, 5.8-6 min, isocratic 10 % B. Solvent A was water, 0.1% aq. formic acid, 0.05% heptafluorobutyric acid and solvent B was acetonitrile, 0.1% aq. formic acid, 0.05% heptafluorobutyric acid. Injection volume was 2 μl. Analytes were ionized using a TurboV ion source equipped with an Assy 65 μm ESI electrode in positive ion mode. The following instrument settings were applied: nebulizer and heater gas, zero grade air, 25 and 10 psi; curtain gas, nitrogen, 20 psi; collision gas, nitrogen, medium; source temperature, 200 °C; ionspray voltage, 5000 V; entrance potential, 10 V; collision cell exit potential, 5 V. The transitions monitored for putrescine were: Q1 mass 89.1 Da, Q3 mass 82.0 Da, declustering potential 22 V, collision energy 14 eV. Acquired MRM data were analyzed using ABsciex MultiQuant software.

Targeted analysis of polyamines in R. solanacearum cells

To analyze polyamine profiles of R. solanacearum cell fractions, R. solanacearum GMI1000 and ΔspeC were seeded into 30 ml MM, MM with 500 μM putrescine, or MM with 500 μM spermidine (OD600=0.015). Cells were grown at 28°C with shaking until to OD600 > 0.8. Cell pellets (1.3×1010 CFU) were washed and stored at -80°C until lysis. Pellets were suspended in 750 μl lysis buffer (100 mM MOPS, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2 pH 8.0) and lysed by ten 30 s rounds of pulsed sonication. During sonication, samples were kept in a salted ice bath. Proteins were precipitated with 225 μl 40% trichloroacetic acid. After 5 min incubation on ice, samples were centrifug (10 min at > 10,000 × g). The supernatant containing the polyamine lysate was stored at -80°C until benzoyl chloride derivatization.

Polyamines were derivatized by adding 1 ml of 2 N NaOH and 10 μl benzoyl chloride to 200 μl cell lysate. Samples were vortexed for 2 min, and incubated at 22°C for 1 h. Saturated NaCl (2 ml) was added, and samples were vortexed for 2 min. After addition of 2 ml diethyl ether, samples were vortexed for 2 min and incubated at 22°C for 30 min. The upper diethyl ether phase containing benzoylated polyamines was removed to a fresh glass tube and evaporated to dryness in a fume hood. For LC-MS analysis, benzoylated samples were dissolved in methanol with 0.1% v/v formic acid and run on an Agilent Infinity LC-MS or Agilent 1100 series LC-MS, with electrospray probes, using a 4.6 × 150 mm (5 μm) Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Samples were injected using an autosampler. The solvent system was 30% solvent A (HLPC grade water with 0.1% v/v formic acid) and 70% solvent B (HPLC grade acetonitrile with 0.1% v/v formic acid). Column flow at 22°C was 0.5 ml min-1, and the analysis time was 20 min.

To analyze polyamine profile of the R. solanacearum ΔRSp1578 mutant, cell lysates grown in MM were prepared as described above. Polyamines were derivatized with dansyl chloride as described (Ducros et al., 2009) with the following modifications. Proteins were precipitated with 1 ml HCl instead of perchloric acid. For HPLC analysis, samples were dissolved in 200 μl ACN, and run on a Zorbax Eclipse Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column. A gradient was run using solvent A (water) and solvent B (100% ACN): 2 min 40% B, 15 min gradient 40-100% B, 2 min 100% B, 7 min 100% B, 4 min gradient 100-40% B, and 2 min 40% B at 37°C, and a flow rate of 0.4 ml min-1 was used.

SpeC overexpression and purification

The R. solanacearum speC gene (RSc2365) with codons optimized for expression in E. coli was synthesized by GenScript and recombined into BamHI/HindIII sites of pET28b-TEV, yielding pET28b-TEV-speC. Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). E. coli cells containing the expression construct were grown at 37°C in 40 ml LB with kanamycin. 20 ml of the overnight culture was added to 2 L LB with kanamycin and grown at 37°C. When cells reached mid-log phase (OD600=0.5), protein expression was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and cells were cultured overnight at 16°C. The cells were re-suspended in 100 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 20 μM PLP, 0.02% Brij-35 detergent and lysed in a cell disruptor at 10,000 psi. The lysate was centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 60 min to remove unbroken cells, debris and insoluble material. The soluble sample was applied to a 5 ml HiTrap chelating HP column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburg PA) equilibrated with 0.1 M NiSO4 and buffer A (100 mM HEPES buffer pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 20 μM PLP, 0.02% Brij-35, and 5 mM imidazole,). The 6xHis-tagged SpeC protein was eluted from the column with a gradient of 0–40% buffer B (100 mM HEPES buffer pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 20 μM PLP, 0.02% Brij-35, and 500 mM imidazole) over 20 column volumes. Proteins were desalted into 10 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol at 4°C using Hi-prep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare). Protein purity was confirmed using SDS-PAGE. Protein concentration was determined in a BioTek Synergy Multi-Mode Microplate reader using the molecular weight and protein extinction coefficients program, which measures absorbance at 280 nm. Protein yield from the induced cultures harboring the expression constructs was 113.1 mg L-1.

In vitro decarboxylase assay

To identify SpeC substrate(s), decarboxylase activity of purified SpeC was measured with the Infinity Carbon Dioxide Liquid Stable Reagent kit (Thermo Scientific). This kit couples CO2 production to phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and malate dehydrogenase. CO2 production is indirectly measured as reduced absorbance at 340 nm as malate dehydrogenase oxidizes NADH to NAD+. All reactions were performed in 200 μl volumes and using buffer 100 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 50 μM PLP, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM of each test substrate (L-ornithine, L-lysine, or L-arginine), and 100 μl 50% CO2 detection solution from the kit. Purified SpeC protein was added to wells at 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 nM final concentration and mixed well. Samples were incubated at 25°C for 20 min, then reaction kinetics were measured with the BioTek plate reader set to measure A340 nm every 5 s for 20 min at 25°C.

Substrate competition assay for SpeC enzyme

To determine the substrate preference of SpeC decarboxylase, purified enzyme was incubated in equimolar L-ornithine and L-lysine. All reactions were performed in 200 μl volumes. Reaction buffer was 100 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 50 μM PLP, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM L-ornithine and 10 mM L-lysine. Reaction was started by adding 2 μM purified SpeC and mixing well. Reactions were carried out for 1 h at 22°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml 2 N NaOH, and polyamines were derivatized with benzoyl chloride as described above. Benzoylated reaction products were analyzed by LC-MS. Ornithine decarboxylase activity yielded benzoylated putrescine, and lysine decarboxylase activity yielded benzoylated cadaverine.

qRT-PCR

Expression of tomato polyamine biosynthesis genes in stems of cv. Money Maker was measured in healthy plants and soil-soak inoculated plants showing early symptoms (<25% wilted leaflets). Stem slices (100 mg) were harvested at the site of inoculation, flash frozen, and stored at -80°C until RNA extraction. For time course experiments, the cut-petiole inoculation method was used to ensure synchronous infection. RNA was extracted at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post inoculation from stem slices at the site of inoculation (including the petiole stump).

RNA was extracted from plant tissue using the RNeasy Plant kit, including DNase treatment (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng to 1 ug RNA with SuperScript III (Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA). Absence of DNA contamination was confirmed by running qPCR reactions on RNA. qPCR reactions were run in triplicate with 10 ng cDNA and EvaGreen qPCR mastermix (BullsEye, Madison, WI) in 25 μl volume in an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative expression of target genes was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCT method, normalizing to the constantly expressed gene ACTIN and to gene expression in healthy tissue (Milling et al., 2011). All primer sets amplified a 100-200 bp fragment with 95-105% amplification efficiency. Sl_ODC2 was not investigated because four attempts to design gene-specific primers yielded unacceptable amplification efficiencies. Primers are listed in Table S2.

Tomato root RNA-seq

Bonny Best tomato seed were surface-sterilized by shaking in 10% bleach for 10 min, followed by shaking in 70% ethanol for 5 min. Seeds were washed repeatedly in sterile water and placed in the refrigerator overnight to synchronize germination. The following day, seeds were placed on germination plates (1% water agar) and plates were placed in the dark for three days. Germinated seeds were sown onto the surface of 0.5× Murashige and Skoog Basal Salts Medium plus Gamborg's vitamins (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) and 1% Agar and incubated at 28°C with a 12 h light cycle. Root tips were inoculated 2 days later with 1 microliter of water (mock) or a bacterial suspension of R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 at OD600=0.2, corresponding to approximately 2 × 105 CFU per plant. After 24 h, root segments spanning the inoculation point (1 inch above, down to the root tip) were collected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C prior to RNA isolation. RNA was prepared from 20-30 root segments using the Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) protocol with modifications for tissues with high polysaccharide content. On average, 25 micrograms of total RNA were isolated from each preparation.

For RNA-seq experiments, three independent biological replicates for each condition were sequenced at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center. Samples were sequenced using paired-end, random primed, multiplexed sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). RNA-seq analysis was conducted in the Galaxy environment (https://galaxyproject.org/) (Giardine et al., 2005; Blankenberg et al., 2010b; Goecks et al., 2010) at the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute using the Tuxedo Suite software (Trapnell et al., 2012). Sequences were trimmed using Fastq Trimmer to remove low quality bases (Blankenberg et al., 2010a), and sequences shorter than 20 nucleotides were discarded as they can have difficulty with genome alignment. Because this quality control step resulted in some single sequences, both single and paired-end sequences were mapped independently using TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009), and these files were merged. Transcripts were then assembled using Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010; Trapnell et al., 2012), and a final transcriptome assembly was created using Cuffmerge (Goecks et al., 2010; Trapnell et al., 2010). Differentially expressed genes were identified using Cuffdiff (Trapnell et al., 2012). Expression changes were considered significant for q-values of <0.05.

Putrescine treatment of plants

Tomato and tobacco leaves and roots were treated with 0.5 mM putrescine in water by spraying leaves until drip-off and pipetting 10 ml into the soil. Water treatment served as a control. After 3 h, tobacco plants were leaf-infiltrated with R. solanacearum K60 as described above, and tomato plants were cut petiole-inoculated with a 2 μl suspension containing 50 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000 on susceptible tomato cvs. Bonny Best and Money Maker. Quantitatively resistant tomato line H7996 was inoculated with 5×103 CFU R. solanacearum UW551 or 5×104 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000. Disease progress assays were conducted as described above. To measure the effect of putrescine on defense gene expression, RNA was extracted from stem at 48 hpi as described above. Xylem sap was harvested at 3 and 24 h post treatment as described above.

Stomatal conductance

Stomatal conductance was measured with a Licor 6400XT portable photosynthesis system gas analyzer. Settings were used that matched environmental measurements of the growth chamber: 700 ppm reference CO2, 400 μmol s-1 flow, 27°C leaf temperature, 350 μmol m-2 s-1. Equilibrium measurements were recorded on one to three fully expanded leaves per plant two to four h after light onset. Tomato leaves rarely filled the full 2 × 3 cm gas analyzer chamber, so leaves were subsequently imaged in a custom-rig to normalize stomatal conductance measurements by percent leaf area.

R. solanacearum biofilm and twitching assays

PVC plate biofilm assays were performed as described (Tran et al., 2016b) except that 0 mM, 1 mM, or 30 μM putrescine was added to CPG broth. Twitching assays were performed as described (Liu et al., 2001) with freshly poured CPG plates with or without 1 mM putrescine.

Supplementary Material

Dataset S1: Relative quantification of metabolites in tomato xylem sap.

(A) Comparison of metabolites in healthy vs R. solanacearum-infected sap. (B) Comparison of metabolites in R. solanacearum-infected tomato sap with or without 3 h incubation with R. solanacearum GMI1000.

Figure S1. Effect of bacterial wilt disease on tomato xylem sap pH and xylem physiology.

(A) Xylem sap pH (n=5) and (B) rate of xylem sap exudation from de-topped tomato stems (*P<0.0001 t-test; n≥69 plants). Samples are from cv. Bonny Best tomato plants soil-soak inoculated with R. solanacearum GMI1000 (Infected) or water (Healthy). Sap was harvested when plants displayed first wilting symptoms. (C) Stomatal conductance of Bonny Best tomato leaves was measured with a Licor Photosynthesis instrument. Turgid leaves from healthy plants and apparently turgid and wilted plants from symptomatic plants soil-soak inoculated with R. solanacearum GMI1000 were analyzed; n≥18, letters indicate P<0.05 by ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Figure S2. Growth of diverse R. solanacearum strains in ex vivo xylem sap from healthy tomato plants or from plants infected with R. solanacearum GMI1000.

(A) Growth of R. solanacearum GMI1000 in sap from tomato cv. Money Maker plants resembles growth in sap from GMI1000-infected tomato cv. Bonny Best plants shown in Fig. 1. (B) Aerobic and microaerobic (0.1% O2) growth of R. solanacearum GMI1000 in xylem sap from tomato cv. Bonny Best tomato plants. (C) Growth of diverse R. solanacearum strains (phylotype IIB UW551, phylotype IIB IBSBF1503, phylotype IIB UW163, phylotype IV Blood disease bacterium (BDB) R229, phylotype IV PSI07, phylotype IV R. syzygii R24) in xylem sap from tomato cv. Bonny Best plants. n≥3 pools of xylem sap for all growth experiments. Data are mean ± SEM.

Figure S3. Loadings for partial least squares analyses of metabolomics data.

(A) Relative amounts of metabolites from healthy tomato sap vs. R. solanacearum-infected sap as detected by untargeted GC-MS analysis. (B) Comparison of metabolomic changes in ex vivo sap after 3 h incubation with R. solanacearum.

Figure S4. Growth of R. solanacearum GMI1000 on metabolites enriched or depleted in xylem sap from R. solanacearum GMI1000-infected tomato plants vs. healthy plants.

Metabolites (identified as shown in Fig 1) were tested as sole carbon sources (black) and sole nitrogen sources (blue) at 10 mM unless otherwise indicated. Dashed lines show negative controls lacking either carbon or nitrogen sources and solid lines show growth on test metabolites. Area under curve (AUC ± standard error) is indicated for metabolites that supported growth. N=3.

Figure S5. Growth of R. solanacearum GMI1000 on metabolites that were depleted in ex vivo sap incubated for 3 h with R. solanacearum.

Metabolites (identified as shown in Fig 2 and S3B) were tested as sole carbon sources (black) and nitrogen sources (blue) at 10 mM in minimal medium unless otherwise indicated. Area under growth curve (AUC ± standard error) is indicated for metabolites that supported growth. N=3.

Figure S6. Xylem sap from tomato plants infected with V. dahliae has enriched putrescine.

Xylem sap was harvested at symptom onset from tomato plants (cv. Money Maker) infected wilt fungus Verticillium dahliae; water-inoculated plants served as controls. Putrescine was measured by LC-MS. Values are mean ± SEM. (*P<0.05 vs. healthy, t-test, n≥3 pools).

Figure S7. Polyamine profile of R. solanacearum cells and substrate specificity of RSc2365 SpeC.

(A) Polyamine profile of R. solanacearum cell pellets grown in defined medium as determined by LC-MS analysis of the cellular benzoylated polyamines. R. solanacearum GMI1000 and ΔspeC mutant strains were grown in minimal medium with or without 500 μM putrescine (Put) or spermidine (Spd). Extracted ion chromatograms are shown for dibenzoylated putrescine (296.7; 297.7); tribenzoylated 2-hydroxyputrescine (416.7; 417.7); tribenzoylated spermidine (457.7; 458.7). The mass spectrum for the 2-hydroxyputrescine peak at 4.017 min is indicated by an asterisk in the GMI1000 sample; a peak of 417.2 (m/z) for 2-hydroxyputrescine is found, along with the sodium adduct at +22 (m/z 439.1). Boxes indicate the peaks corresponding to putrescine, 2-hydroxyputrescine, and spermidine. Representative results from lysates analyzed in triplicate are shown. (B) Substrate specificity of RSc2365 decarboxylase was determined by a ornithine/lysine substrate competition in vitro assay using recombinant SpeC. Purified SpeC protein (2 μM) was assayed for 1 h at 22°C in the presence of equal amounts (10 mM) of both L-lysine and L-ornithine. After benzoylation of the products, the resulting diamines (putrescine and cadaverine) were detected by LC-MS. Extracted Ion Chromatograms (EIC) for the mass of dibenzoylated putrescine (296.7; 297.7) and dibenozylated cadaverine (310.7; 311.7) are shown. Identity of the peak for dibenzoylated putrescine (3.440 min) was confirmed by the presence of the corresponding mass (m/z 297.1 and sodium adducted form at m/z 319.1) in the mass spectrum (inset).

Figure S8. The RSp1578 locus (encoding a putative agmatinase) does not contribute to R. solanacearum putrescine production or R. solanacearum virulence.

(A) Genomic context of RSp1578 in the R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 genome. Dashed line indicates region deleted ΔRSp1578 mutant. (B) Polyamine profile of GMI1000 and ΔRSp1578 mutant. Cell lysate polyamines were derivatized with dansyl chloride. HPLC trace (fluorescence excitation: 333 nm; emission: 518 nm) of representative samples. Peaks corresponding to putrescine, cadaverine, and internal standard 1,8-diaminooctane (DAO). Representative results are shown for lysates analyzed in triplicate. (C) Virulence of the ΔRSp1578 mutant on wilt-susceptible tomato cv. Bonny Best after soil soak inoculation (5×108 CFU g-1 soil) or stem inoculation (103 CFU). Values are mean ± SEM (n=45 plants/treatment).

Figure S9. In vitro and in planta growth of ΔspeC mutant and its genetic complement.

(A) Genomic context of speC gene (RSc2365). Dashed line indicates the region replaced by the spectinomycin cassette in the ΔspeC mutant. Solid line indicates the region used to complement the ΔspeC mutant using the predicted native promoter. (B) Effect of overnight culture conditions on growth of ΔspeC mutant in minimal medium (MM). Strains were incubated overnight in CPG or CPG with 100 μM putrescine, washed, and resuspended in media as indicated in figure (n=3). (C) Growth of GMI1000 (WT), ΔspeC mutant, and the complemented ΔspeC mutant (speC Comp) in MM with (grey bars) or without 30 μM putrescine (black bars). (D) Structures of putrescine, spermidine, cadaverine, and agmatine, and (E) ability of 30 μM or 100 μM of these compounds to restore growth of ΔspeC mutant when added to MM (n=3). (F) Stem population sizes of ΔspeC mutant in tomato cv. Money Maker plants was measured 3 d after stem inoculation with 103 to 108 CFU (n=5 plants per condition). (G) Stem population sizes of WT GMI1000, ΔspeC mutant, and complemented mutant either alone or co-inoculated as indicated in tomato cv. Money Maker plants, measured at indicated times after stem inoculation with 103 to 108 CFU (n=5 plants per condition).

Figure S10. Expression of tomato putrescine biosynthesis genes during bacterial wilt disease.

(A) Tomato putrescine biosynthesis pathway. (B) Gene expression of tomato cv. Money Maker after naturalistic soil-soak inoculation with R. solanacearum (5×108 CFU g-1 soil) or water. Stem RNA was extracted from healthy or symptomatic infected plants and analyzed by RT-qPCR with normalization to ACTIN. Values are mean ± SEM (n=5) * indicates expression levels differ from healthy plants at P<0.005, one-sample t-test. (C-E) Tomato polyamine biosynthesis gene expression after stem inoculation. Polyamine biosynthesis genes are identified by color as indicated. Tomato plants (cv. Money Maker) were cut-petiole inoculated with 103 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000, 108 CFU ΔspeC (Put-), or 108 CFU ΔhrcC (T3SS-). (C) Population sizes of the three bacterial strains over time in stems directly below the inoculation site. Dashed lines indicate inoculum density at t=0. Values are geometric mean ± SEM (n=3). (D) Time-course expression of polyamine biosynthesis genes in tomato stems infected with R. solanacearum GMI1000. (E) Expression of Sl_ADC1 at 48 hpi in tomato stem tissue with equal bacterial burden of R. solanacearum GMI1000, ΔspeC (Put-), ΔhrcC (T3SS-), relative to gene expression in healthy plants. Values are mean ± SEM (n=3).

Figure S11. Effects of putrescine treatment on healthy and R. solanacearum-infected tomato plants and on R. solanacearum behavior in vitro.

Putrescine (0.5 mM) or water (control) was applied to tomato plants by foliar spray and soil soak. (A-B) At 3 h post putrescine treatment, tomato (A) susceptible Bonny Best (P=0.0151 repeated measures ANOVA; n=180 plants/treatment) or (B) resistant Hawaii7996 (H7996) (P=0.8121; n=30 plants/treatment) were stem inoculated with (A) 50 or (B) 50,000 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000. Symptom development was measured using a disease index corresponding to percent of wilted leaflets. Values are means ± SEM. (C-D) Effect of putrescine treatment on putrescine levels in xylem sap as measured by (C) LC-MS quantification and (D) growth of R. solanacearum ΔspeC putrescine biosensor strain in xylem vessels. (C) Xylem sap of non-infected plants was harvested at 3 and 24 h after putrescine treatment, and putrescine was measured with LC-MS. Values are means ± SEM (n=3). (D) Leaves and soil of tomato plants were treated with 0.5 mM putrescine or water every 24 h for three treatments. At 3 h after first treatment, 104 CFU ΔspeC were inoculated into the stem. Bacterial population size was determined at 72 h post inoculation by dilution plating ground stem sections. Horizontal line shows geometric mean (n=5). (E) Effect of putrescine on root pressure-driven sap exudation of R. solanacearum-infected tomato cv. Money Maker plants. Plants were stem inoculated with 50 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000. Sap exudation rate of detopped plants was measured for 30 min (n≥26). (F) Leaf stomatal conductance of control or putrescine-treated tomato cv. Money Maker plants was measured by Licor 6400 XT portable photosynthesis system at 24 to 72 h after stem inoculation with 50 CFU R. solanacearum GMI1000; (n≥30 plants/treatment). (G) Effect of putrescine on R. solanacearum GMI1000 in crystal violet polyvinylchloride attachment assay. R. solanacearum was grown in CPG with 0, 30 μM, or 1 mM putrescine. Letters indicate P<0.05 by ANOVA with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. Values are means ± SEM (n=60).

Figure S12. Effect of putrescine treatment and R. solanacearum infection on expression of tomato defense genes.

Plants were cut petiole- inoculated with 50 CFU and RNA was extracted at 48 hpi. Plant gene expression was normalized to ACTIN transcript levels. Values are mean ± SEM. Letters indicate P<0.05 by ANOVA with Tukey test for multiple comparisons (n=7 plants/treatment).

Table S1: Expression of tomato polyamine metabolism genes in healthy and GMI1000-infected tomato (cv. Bonny Best) seedling roots.

Table S2: Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study.

Statement of Originality and Significance.