Abstract

Background

Here, we generated human cardiac muscle patches (hCMPs) of clinically relevant dimensions (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm) by suspending cardiomyocytes, smooth-muscle cells, and endothelial cells that had been differentiated from human induced-pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) in a fibrin scaffold and then culturing the construct on a dynamic (rocking) platform.

Methods

In vitro assessments of hCMPs suggest maturation in response to dynamic culture stimulation. In vivo assessments were conducted in a porcine model of myocardial infarction (MI). Animal groups included: MI hearts treated with two hCMPs (MI+hCMP, N=13), treated with two cell-free open fibrin patches (MI+OP, n=14), or with neither experimental patches (MI, n=15); a fourth group of animals underwent sham surgery (SHAM, n=8). Cardiac function and infarct size were evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging, arrhythmia incidence by implanted loop recorders, and the engraftment rate by calculation of quantitative PCR measurements of expression of the human Y chromosome. Additional studies examined the myocardial protein expression profile changes and potential mechanisms of action that related with exosomes from the cell patch.

Results

The hCMPs began to beat synchronously within 1 day of fabrication, and after 7 days of dynamic culture stimulation, in vitro assessments indicated the mechanisms related to the improvements in electronic mechanical coupling, calcium-handling, and force-generation suggesting a maturation process during the dynamic culture. The engraftment rate was 10.9±1.8% at 4 weeks after the transplantation. The hCMP transplantation was associated with significant improvements in left ventricular (LV) function, infarct size, myocardial wall stress, myocardial hypertrophy, and reduced apoptosis in the peri-scar boarder zone myocardium. hCMP transplantation also reversed some MI-associated changes in sarcomeric regulatory protein phosphorylation. The exosomes released from the hCMP appeared to have cytoprotective properties that improved cardiomyocyte survival.

Conclusions

We have fabricated a clinically relevant size of hCMP with trilineage cardiac cells derived from hiPSCs. The hCMP matures in vitro during 7 days of dynamic culture. Transplantation of this type of hCMP results in significantly reduced infarct size and improvements in cardiac function that are associated with reduction in LV wall stress. The hCMP treatment is not associated with significant changes in arrhythmogenicity.

Keywords: Heart, Myocardial Infarction, Tissue Engineering, Porcine

INTRODUCTION

The human induced-pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) technology has advanced medical science significantly. A number of studies have shown that when hiPSCs are differentiated into cardiomyocytes and evaluated in rodent, swine, and non-human primate (NHP) models of myocardial infarction (MI), the treatment is associated with functional improvement.1–4 However, in NHP models of MI when the dose and grafts are large enough, the cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or NHP iPSCs have been associated with increased incidences of ventricular arrhythmias.2, 5 The hiPSCs and hESCs are pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), and PSCs derived cardiomyocytes are structurally and functionally similar to neonatal cardiomyocytes,6, 7 which may limit their contractile activity and could lead to electrical instability after graft into recipient adult hearts. The previously reported preclinical trials of cardiac tissue engineering therapy of rodent models utilized relatively small and thin fabricated cardiovascular tissues, 8 which are limitations from the clinical perspective. Thus, methods for fabrication of larger and thicker functional cardiac tissue, and methods for promoting the maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from hPSCs are urgently needed.

Cardiac tissue patch based approaches for cell delivery is more effective from engraftment rate perspective because the unique characteristics of high pressure and high flow of the left ventricle (LV).8–13 Cardiac muscle patch could also provide the structural strengthening the injured LV, thereby preventing the LV dilation and the over stretching of the border zone (BZ) myocardium.1, 6, 12, 14, 15 Notably, the cardiomyocytes present in three-dimensional (3D), engineered human cardiac muscle patches (hCMPs) are more mature than those obtained via monolayer culturing techniques,6, 11, 16 and hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) assumed a more mature and structurally aligned phenotype after transplantation when the hiPSC were reprogrammed from cardiac-lineage cells (hciPSCs) rather than from dermal fibroblasts or umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells.17 However, most of the hiPSC-hCMPs have been too small and too thin from the translational perspective.1, 18, 19

Previously, we have shown that cardiomyocytes are more resistant to hypoxic injury when co-cultured with endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) than when cultured alone,3, 20 and that the engraftment of transplanted cardiomyocytes, as well as measurements of myocardial perfusion, metabolism, and contractile activity, improves when the cells are co-administered with ECs and SMCs.3 Thus, for the experiments described in this report, hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, ECs (hiPSC-ECs), and SMCs (hiPSC-SMCs) were differentiated from hciPSCs,17 seeded into a 3D fibrin scaffold to fabricate a novel type of hCMP with clinically relevant size and thickness (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm), and subsequently cultured with dynamic and mechanical stimulation to promote maturation. The effectiveness of these hCMPs for improving cardiac function after myocardial injury was then evaluated in a large animal model of MI.

METHODS

The data, analytic methods, and study materials are made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.21 A detailed description of the experimental procedures used in this study is provided in the online Supplement. All procedures and protocols involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and performed in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM), and were tested for significance level of type I error (P<0.05) via the Student’s t test or ANOVA for differences between the values. The Bonferroni correction for the significance level was used to take into account of multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Differentiation and characterization of hiPSC-CMs, -SMCs, and -ECs

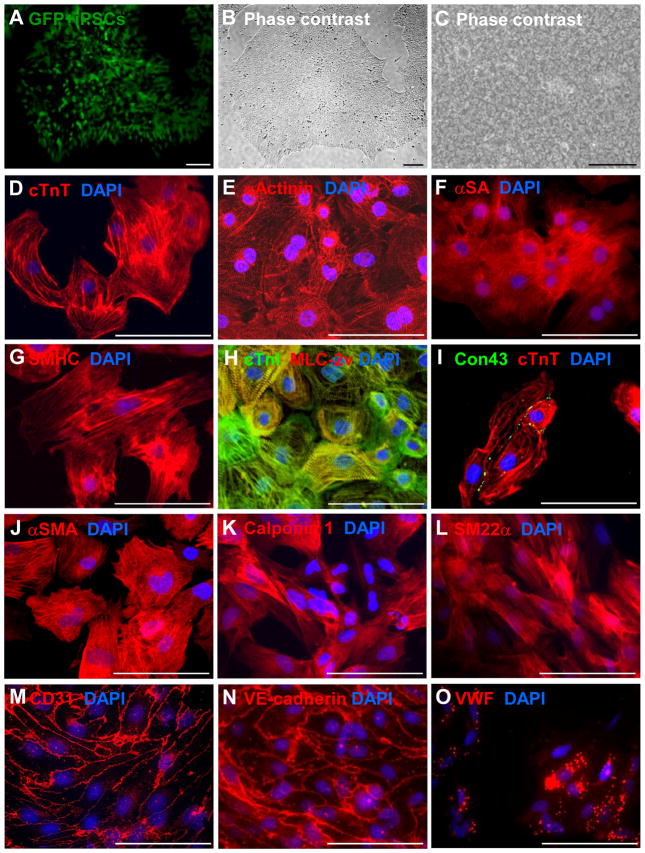

hiPSCs were reprogrammed from human cardiac fibroblasts, engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Figures 1A–1C), and then differentiated into hiPSC-CMs, -ECs, and -SMCs as previously reported.3, 22–24 Spontaneous contractions (Supplemental Video 1) were typically observed in hiPSC-CMs on day 8 after differentiation was initiated, and the number of contracting cells usually increased up to day 12. One week after purification, the hiPSC-CMs (Figures 1D–1I) expressed cardiac troponin T (cTnT), α sarcomeric actinin (αActinin), α sarcomeric actin (αSA), slow cardiac myosin heavy chain (SMHC), cardiac troponin I (cTnI), and ventricular myosin light chain 2 (MLC-2v), and the gap-junction protein cardiac connexin 43 (Con43) was commonly observed between adjacent cells. hiPSC-SMCs (Figures 1J–1L) and hiPSC-ECs (Figures 1M–1O) expressed SMC-specific (α smooth-muscle actin [αSMA], calponin 1, and smooth muscle 22 alpha [SM22α]) and EC-specific (CD31, vascular endothelial cadherin [VE-cadherin], and von Willebrand factor [VWF]) markers, respectively, and when stimulated with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), the hiPSC-ECs formed tube-like structures in Matrigel (Supplemental Figure 1A). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that each of the final hiPSC-derived cell populations was at least 90% pure: 96.4% of the hiPSC-CMs expressed cTnT (Supplemental Figure 1B), 91.5% of the hiPSC-SMCs expressed αSMA (Supplemental Figure 1C), and >95% of the hiPSC-ECs expressed CD31 and/or VE-cadherin (Supplemental Figures 1D and 1E).

Figure 1. Characterization of human induced-pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and hiPSC-derived cardiac cells.

The hiPSCs used for this investigation were reprogrammed from human left atrial fibroblasts and (A) engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP). When cultured as a monolayer with Matrigel, (B) the cells grew to form flat, compact colonies with distinct cell borders (magnification: 40×) and displayed the morphological characteristics of hiPSCs, including (C) prominent nuclei and a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio (magnification: 100×). (D–I) hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) were characterized via immunofluorescent analyses of (D) cardiac troponin T (cTnT), (E) α-sarcomeric actinin (αActinin), (F) α-sarcomeric actin (αSA), (G) slow myosin heavy chain (SMHC), (H) cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and myosin light chain 2v (MLC-2v), and (I) connexin43 (Con43) and cTnT expression. (J–L) hiPSC-derived smooth muscle cells (hiPSC-SMCs) were characterized via immunofluorescent analyses of (J) α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), (K) calponin 1, and (L) smooth muscle 22 alpha (SM22α) expression. (M–O) hiPSC-derived endothelial cells (hiPSC-ECs) were characterized via immunofluorescent analyses of (M) CD31, (N) vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), and (O) von Willebrand factor (VWF) expressions. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI). Bar = 100 μm.

Fabrication and characterization of large, thick, hiPSC-derived, human cardiac-muscle patches (hCMPs)

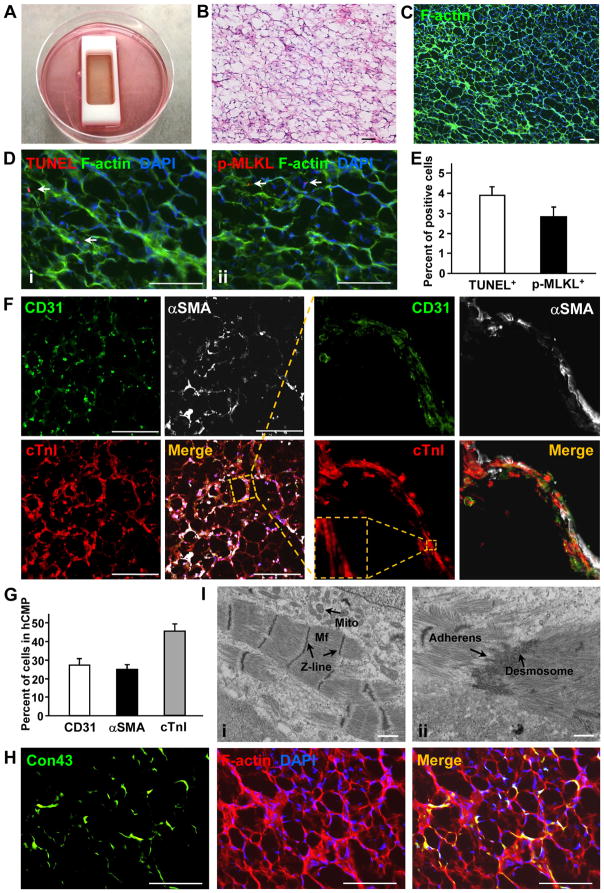

Large and thick hCMPs (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm) were fabricated in vitro by mixing a fibrinogen solution containing 4 million hiPSC-CMs, 2 million hiPSC-ECs, and 2 million hiPSC-SMCs with thrombin, and then quickly adding the mixture to a mold (Figure 2A). The mixture solidified within a few minutes, and the patches were cultured on a dynamic (rocking, 45 rpm) platform for 7 days before subsequent in-vitro analyses were performed (Supplemental Video 2). The hiPSC-CMs began to beat synchronously across the entire hCMP within one day of seeding (Supplemental Video 3); by day 7, the amplitude of contraction was noticeably greater (Supplemental Video 4), while the expression of genes required for contractile function (cTnT, cTnI, α myosin heavy chain [αMHC], and cardiac actin 1 [cActin1]) and for generating calcium transients (ryanodine receptor 2 [RYR2], sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 [SERCA2], Con43) was significantly greater in the hCMPs than in monolayers of equivalent populations of hiPSC-derived cardiac cells (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 1). cTnT, cTnI, RYR2, and SERCA2 protein levels were also greater in the dynamically cultured hCMPs than in hCMPs that had been grown under static culture conditions (Supplemental Figure 3A and 3B), and observations of hCMPs stained with phalloidin (Figure 2B) (to visualize F-actin) or hematoxylin and eosin (Figure 2C) suggested that they could be easily permeated by the culture medium. Less than 5% of the cells displayed evidence of apoptosis or necrosis (i.e., positive staining for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) or phosphorylated mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase [pMLKL], respectively) (Figures 2D and 2E), while analysis of hCMPs that had been stained for the endothelial marker CD31, the SMC marker αSMA, and the CM specific protein cTnI confirmed that the three cell types interacted with each other (Figure 2F, Supplemental Figure 3C), and that the original 2:1:1 ratio of hiPSC-CMs, -SMCs, and -ECs was largely retained at day 7 (Figure 2G). Con43 expression was prevalent throughout the hCMPs (Figure 2H), suggesting that the hiPSC-CMs were strongly interconnected, and structures that resembled primitive intercalated discs with stress-transmitting fascia adherens junctions and desmosomes were visible in transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2I).

Figure 2. Characterization of the structure and cellular composition of the human cardiac muscle patch (hCMP).

(A) Large hCMPs (4 cm× 2 cm× 1.25 mm) were fabricated by suspending 4 million hiPSC-CMs, 2 million hiPSC-ECs, and 2 million hiPSC-SMCs in a fibrinogen solution, mixing the cell-containing fibrinogen solution with a thrombin solution, quickly pouring the mixture into a mold (internal dimensions: 4 cm × 2 cm× 1 cm), and then culturing the cells for one week. (B–C) The internal structure of the hCMP was evaluated via (B) hematoxylin/eosin (HE) staining and (C) phalloidin staining to identify the presence of F-actin (bar = 100 μm). (D) Apoptotic and necrotic cells were identified via (Di) terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and (Dii) immunofluorescence staining for phosphorylated mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase (p-MLKL), respectively (bar = 100 μm), and then (E) quantified as the percentage of cells that were positive for each stain (n=4 hCMPs). (F) ECs, SMCs, and CMs were identified in the hCMP via immunofluorescence staining for the presence of CD31, αSMA, and cTnI, respectively (bar = 300 μm); then, (G) the percentage of cells that stained positively for each marker was calculated (n=4 hCMPs). (H) Gap-junctions between adjacent cardiac cells were identified in hCMPs stained for the presence of F-actin and Con43 (bar = 100 μm). (I) The ultrastructure of the hCMP was analyzed by transmission electron microscope to identify (Ii) myofibrils (Mf), Z-lines, mitochondria (Mito) and (Iii) primitive intercalated disc-like structures with fascia adherens junctions and desmosomes. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Functional assessment of hCMPs in vitro

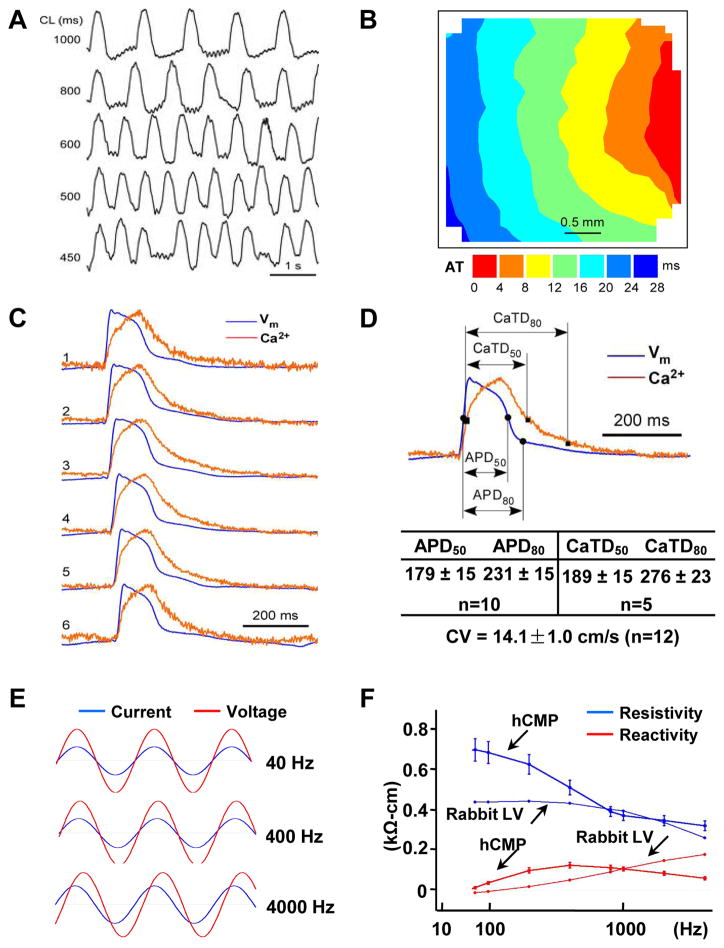

Optical mapping studies confirmed that the transmembrane potential of the hCMPs could be paced at cycle lengths ranging from 1000 ms to 450 ms (Figure 3A). When paced at 800 ms (Figures 3B and 3C), the average conduction velocity was 14.1±1.0 cm/s; the average durations of the action potential until 50% (APD50) and 80% (APD80) repolarization were 179±15 and 231±15 ms, respectively; and the average Ca2+ transient durations until 50% (CaTD50) and 80% (CaTD80) relaxation were 189±15 and 276±23 ms, respectively (Figure 3D). Furthermore, when a linear array system of electrical sensors was used to evaluate intercellular coupling (Figure 3E), the results from assessments in the hCMPs were similar to those in myocardium from the left ventricles of rabbits (Figure 3F). The data suggest that gap-junction communication in the hCMPs at day 7 of dynamic culture is comparable to that observed in native myocardium, at least from the perspective of intercellular impedance.

Figure 3. Characterization of hCMP electrophysiology and function.

(A–D) Action potential (AP) propagation and Ca2+ transient kinetics were evaluated in hCMPs 7 days after manufacture by staining hCMPs with a voltage-sensitive dye (RH-237, for AP assessments) or a Ca2+-sensitive dye (Cal-520FF, for Ca2+ transient measurements) and then measuring the intensity of transmitted light. (A) Traces (i.e., light intensity) were recorded at the indicated cycle lengths (CL). (B) Isochronal maps of AP propagation (AT: activation time) and (C) optical traces of membrane potential (Vm, blue) and Ca2+ transient traces (red) were recorded during pacing at CL=800 ms and used to determine (D) the conduction velocity (CV), duration of the action potential until 50% and 80% repolarization (APD50 and APD80, respectively), and the duration of the Ca2+ transients until 50% and 80% relaxation (CaTD50 and CaTD80, respectively). (E) Voltage (red) and current (blue) recordings were obtained in hCMPs during stimulation at 40 Hz, 400 Hz, and 4000 Hz; recordings were windowed to enable the current and voltage traces to be compared across 1.5 cycles for each frequency. (F) Tissue resistivity and reactivity in the hCMPs and in rabbit ventricular myocardium (from a previous report39) were summarized as a function of stimulation frequency. (G–L) hCMP force-generation measurements were determined 7 days after hCMP generation. (G) The relationship between force generation and tensile strain was evaluated by recording force traces as the hCMP was stretched from 100% to 121% of slack length over a four-minute period; (H) active and passive force generation was summarized as a function of hCMP length. (I) hCMPs were stretched to 110% of slack length, and force traces were recorded as the hCMPs beat spontaneously (s) or in response electronic pacing at frequencies of 1, 2, and 3 Hz; (J) twitch force was summarized as a function of pacing frequency. (K) hCMPs were stretched to 110% of slack length, and force traces were recorded as the hCMPs beat in the presence of increasing concentrations (0, 0.1 μM, 1 μM) of isoproterenol; (L) twitch force was summarized as a function of isoproterenol concentration. (M–N) Twitch-force was measured at 110% of slack length in hCMPs and in patches that lacked hiPSC-SMCs and ECs but were otherwise identical to the hCMPs; then, force-generation was calculated (M) for the entire hCMP or patch and (N) per cardiomyocyte in the hCMP or the patch. CM: cardiomyocyte; EC: endothelial cell; SMC: smooth muscle cell. *p<0.05. n=4–5 in each group.

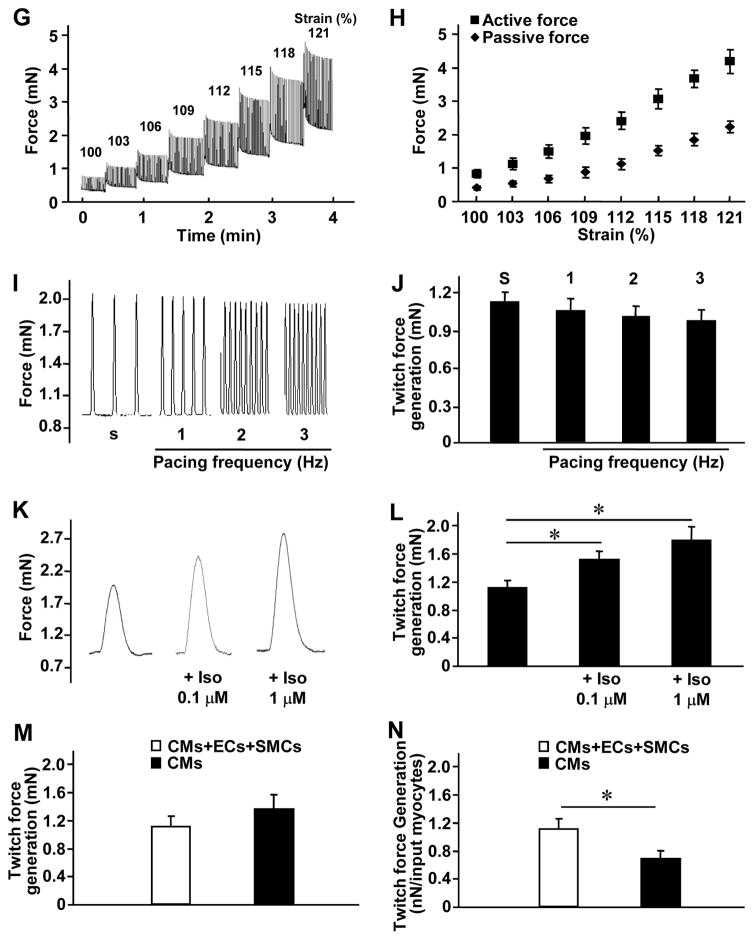

The functional maturation of the hCMPs was evaluated via measurements of force generation. Spontaneous twitch-force generation (Figure 3G) was weak at slack length (i.e., in the absence of stretching), but increased in magnitude as the hCMPs were stretched in 3% increments to 121% of its original slack length (Figure 3H). This finding is consistent with observations that the force of ventricular contraction increases as the muscle fibers stretch in response to larger amounts of blood entering the ventricle (i.e., the Frank-Starling mechanism).25 Spontaneous twitch force transients (at 110% of slack length) also disappeared upon incubation with a reversible inhibitor of the actin-myosin interaction (30 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime [BDM]) but reappeared after the inhibitor was washed out of the medium (Supplemental Figure 4) suggesting hCMP has a normal function in response to cross-bridge inhibition. Studies of pacing-induced contractions indicated that as the frequency increased from 1 to 3 Hz, the magnitude of force generation declined slightly, but not significantly, in the hCMPs (Figures 3I and 3J), which reflects a superior contractile functional benefits of this hCMP with trilineage cardiac cells from hciPSCs,17 with the best ever positive force-frequency relationship than previous hiPSC-hCMP, and similar to what have been observed in adult human cardiomyocytes,1, 6, 10 This may be because of maturation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in the dynamic culture system. Furthermore, force generation in the hCMPs increased in response to higher extracellular calcium concentrations (Supplemental Figure5) and when the hCMPs were cultured with a β-adrenergic agonist (isoproterenol) (Figures 3K and 3L). Collectively, these observations suggest that the force-generation and calcium-handling machinery of the hCMPs was relatively further developed within hCMP in the dynamic culture. Notably, the total amount of force generated by the hCMPs did not differ significantly from the force generated by patches that contained the same total number of cells but were composed of only hiPSC-CMs (Figure 3M); thus, the amount of force generated per cardiomyocyte was approximately twice as great in the hCMPs (Figure 3N). Collectively, these observations indicate that the hCMPs were electrically integrated and exhibited significant functional maturation after 7 days of dynamic culture.

hiPSC-derived cardiac cells engraft and survive after hCMP transplantation into a porcine model of myocardial infarction (MI)

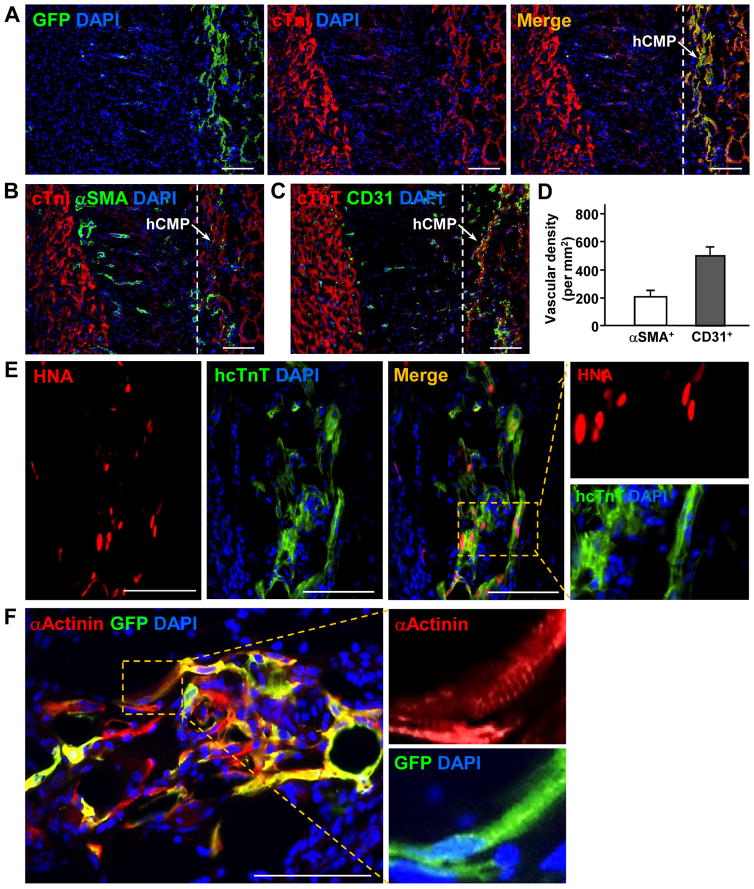

The cardioprotective efficiency of hCMP transplantation was evaluated in a porcine model of MI. MI was surgically induced by occluding the distal left anterior descending coronary artery for 60 minutes before reperfusion, and then two hCMPs were sutured over the site of infarction in animals from the MI+hCMP group (Supplemental Video 5). Two large cell-free open fibrin patches (OPs), which were otherwise identical to the hCMPs, were sutured over the injury site in animals from the MI+OP group, while animals in the MI group recovered without either experimental treatment. A fourth group of animals, the Sham group, underwent all surgical procedures for MI induction except coronary occlusion (Supplemental Table 2). Because the experiments were performed with female pigs, while the transplanted cells were generated from the tissues of male humans and engineered to express GFP, the engraftment and survival rates of the transplanted cells were evaluated via quantitative PCR assessments for the human Y chromosome, and the lineages of the surviving cells were determined via immunofluorescent analyses of the expression of GFP, cTnI, αSMA, cTnT, CD31, human nuclear antigen (HNA), αActinin, and the human-specific isoforms of cTnT (hcTnT), calponin 1 (hCalponin 1), and CD31 (hCD31) (Figure 4). The engraftment rate was approximately 11% (10.9±1.8%, n=6 hearts) at week 4 after treatment, and all three transplanted cell lineages were present in the treated region. Furthermore, GFP+ cells were generally found in clusters (Figure 4A) and interspersed with αSMA+ (Figure 4B) and CD31+ (Figure 4C) structures, indicating that the hCMPs were vascularized (Figure 4D), while the hiPSC-CMs (Figure 4E), though structurally immature, displayed some evidences of sarcomeric organization (Figure 4F). However, only a small proportion (~10%) of the vessels in the patch expressed GFP (Figure 4G), hCalponin 1 (Figure 4H), or hCD31 (Figures 4I and 4J). These data demonstrate that the hiPSC-ECs and -SMCs do incorporate, with small extent, to the vasculature as the native vessels sprouting into the grafted hCMPs, which is consistent with our previous observations in rodent studies.26, 27

Figure 4. hCMPs engraft and survive after transplantation onto infarcted swine hearts.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury was surgically induced in swine hearts, and then two hCMPs were sutured over the site of infarction. Sections taken at week 4 from the region of patch application were immufluorescently stained for the presence of cTnI, cTnT, GFP, human specific nuclear antigen (HNA), human specific TnT (hcTnT), α-sarcomeric actinin (αActinin), αSMA, human specific calponin 1 (hCalponin 1), CD31, and the human isoform of CD31 (hCD31); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (A) Engrafted hiPSC-CMs were identified by the co-expression of GFP and cTnI; the transplanted hCMP is located to the right of the dashed line in the merged image. (B–D) Vascular structures were identified via the presence of (B) αSMA or (C) CD31 expression; then (D) vessel density in the hCMP was quantified by calculating the number of αSMA+ or CD31+ structures per unit area. (E) Engrafted hiPSC-CMs were further identified by the co-expression of HNA or hcTnT. (F) Evidence of maturing sarcomeric structure (insets) was visible in sections stained for the co-expression of GFP and αActinin. (G–H) hiPSC-SMCs were identified as evidence of arterioles within the engrafted patch via the co-expression of (G) αSMA and GFP, or (H) hCalponin 1 and αSMA. (I–J) hiPSC-ECs were identified in (I) the vasculature of the engrafted patch via the expression of CD31 and hCD31; and in (J) arterioles within the engrafted patch via the expression of hCD31 and αSMA. These data indicate that the majority of neovascularization vessels are from angiogenesis, with small portion of the total spouting arterials or arterioles that are involved by vascular genesis. Scale bar = 100 μm.

hCMP transplantation improves myocardial performance, regional wall stress, and limits adverse remodeling after MI

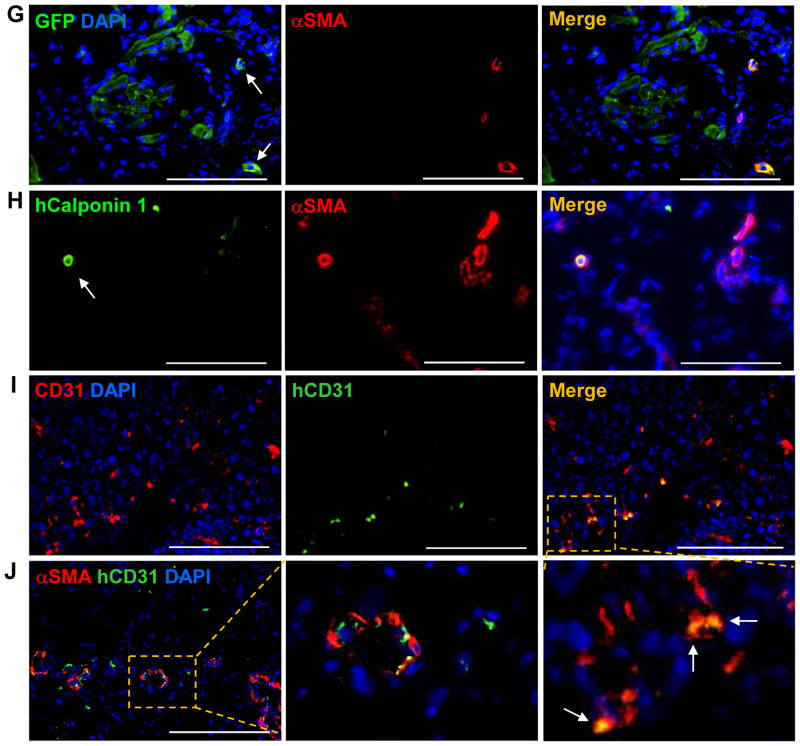

Cardiac function was evaluated 4 weeks after injury via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 5A) and hemodynamic analysis. Measurements of left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) (Figure 5B), LV ejection fraction (EF) (Figure 5C), infarct size (Figure 5D), systolic thickening fractions in the infarcted zone (IZ) of the LV wall and in the peri-scar border zone (BZ) of the infarct (Figure 5E), LV systolic pressure (SP) (Figure 5F), and regional wall stress in both the IZ and BZ (Figure 5G) were significantly better in MI+hCMP animals than in animals from either the MI+OP or MI group. Furthermore, the ratio of LV weight to bodyweight (LVW/BW) (Figure 5H), as well as the cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes located in the BZ (Figures 5I and 5J), in MI+hCMP and Sham animals were similar and significantly lower than in MI+OP or MI animals. Thus, the hCMPs appeared to improve cardiac function, reduce wall stress and infarct size, and limit myocardial remodeling, when transplanted over the infarcted region of swine hearts.

Figure 5. hCMP transplantation improves the recovery of cardiac function and limits adverse remodeling in infarcted pig hearts.

MI was surgically induced in swine hearts by occluding the coronary artery for 60 minutes; then, two hCMPs were sutured over the site of infarction in animals from the MI+hCMP group, two large fibrin patches lacking the hiPSC-derived cardiac cells were sutured over the injury site in animals from the MI+OP group, and animals in the MI group recovered without either experimental treatment. Animals in the Sham group underwent all surgical procedures for MI induction except the occlusion step. (A–E) Four weeks after MI or Sham surgery, (A) magnetic resonance images (left: end systole, right: end diastole) were obtained and used to measure (B) left ventricular end-diastolic volumes (LVEDV), (C) left ventricular ejection fractions (LVEF), (D) infarct sizes, and (E) systolic thickening fractions in the infarcted zone (IZ) of the LV wall, in the border zone (BZ) of the infarct, and in a remote (i.e., noninfarcted) zone (RZ). n=8–10 per experimental group. (F) Hemodynamic measurements. (G) end-systolic LV wall stress in the IZ, BZ and RZ. n=5–7 per experimental group. (H–J) Animals were sacrificed at week 4; then, (H) the LV weight to body weight (LVW/BW) ratios were determined (n=8–11 per experimental group), and (I–J) sections from the border-zone of the infarct were collected and stained with (I) wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and cTnI to visualize cardiomyocytes (n=6–8 per experimental group, scale bar = 100 μm). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and (J) cardiomyocyte cross-sectional surface areas were measured. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

hCMP transplantation does not induce ventricular arrhythmia

Because the potential for arrythmogenic complications may be the most prominent safety concern associated with CM transplantation,28 loop recorders were implanted in a subset of animals from the MI, MI+OP, and MI+hCMP groups, and electrocardiography (ECG) were continuously monitored from before MI induction until four weeks afterward. Although severe arrhythmias and ST-segment elevations occurred in all animals (MI: n=6, MI+OP: n=7, MI+hCMP: n=5) during occlusion and reperfusion and within the first 14 days after the MI, however, after the initial 14 days post AMI, no animal in any group developed spontaneous arrhythmia during the remaining 2-week follow-up period. Furthermore, incidents of ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) were not significantly different between the different groups based on the loop recorder data. In response to programmed electrical stimulation (PES) stimulation protocol, there was no significant increased arrhythmogenicity among the different groups of hearts. Thus, hCMP transplantation did not adversely affect the electrical stability of infarcted swine hearts.

hCMPs secrete exosomes that promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and cell-cycle progression, enhance the angiogenic activity of endothelial cells, and protect cardiomyocytes from hypoxic damage

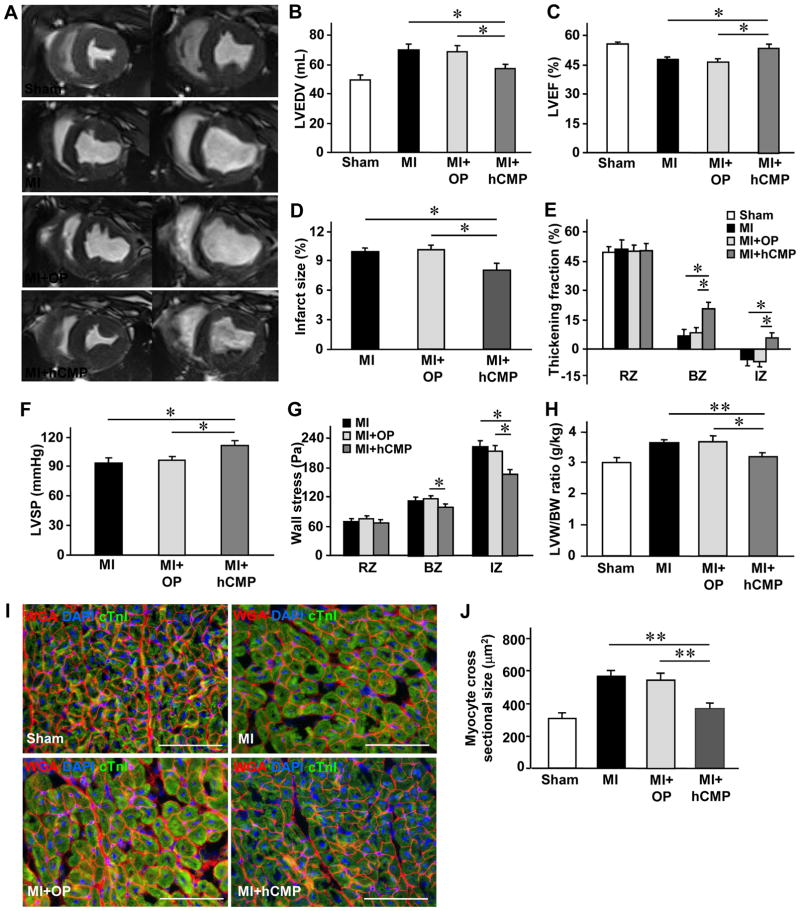

The potentially important role of exosomes in myocardial repair and protection is just beginning to be recognized;29, 30 thus, we studied whether the beneficial paracrine activity associated with hCMP transplantation may have been partially mediated by secreted exosomes. Nanoparticle tracking (Figure 6A) and transmission electron microscopy (Figure 6B) analyses indicated that the exosomes in the hCMP culture medium were typically ~100 nm in diameter and had bi-layered membranes, while Western blots confirmed the presence of the exosomal marker proteins ALG-2-interacting protein X (Alix), tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein (TSG101), CD81, CD63, and CD9 (Figure 6C). Furthermore, images of PKH26 fluorescence indicated that when cardiomyocytes were cultured with PKH26-labeled exosomes, the number of exosomes taken up by the cultured cells increased substantially over 24 hours, which were inhibited by pretreatment with the exosome internalization inhibitor, annexin V31 (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Characteristics and cytoprotective effects of hCMP-secreted exosomes.

Exosomes were isolated from the hCMP culture medium; then, (A) exosome size was evaluated via nanoparticle tracking analysis, (B) exosome morphology was evaluated via electron microscopy (bar = 100 nm), and (C) the presence of exosome marker proteins (ALG-2-interacting protein X [Alix], tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein [TSG101], CD81, CD63, CD9) was evaluated via Western blot. (D) Cardiomyocytes were incubated for 30 minutes or 24 hours with PKH26-labeled hCMP-secreted exosomes that had been pretreated with or without the exosome uptake inhibitor annexin V (2 μg/mL); then, the cardiomyocytes were fixed and immunofluorescently stained for α-actinin, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and exosomes that had been taken up by the cardiomyocytes were identified by PKH26 fluorescence (bar = 100 μm). (E–H) Cardiomyocytes were cultured under hypoxic conditions in serum free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) for 48 h with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with exosomes from hCMPs (hCMP-Exo) that had been treated with or without an exosome-release inhibitor (GW4869, 10 μM) or an exosome-internalization inhibitor (annexin V, 2 μg/mL). (E) The intensity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) fluorescence observed in the media was measured and expressed as a percentage of the intensity observed in PBS-cultured cells. (F) Cell viability was measured with a colorimetric assay that detected the reduction of a tetrazolium compound into a colored formazan product (the conversion occurs through the metabolic activity of living cells), and expressed as a percentage of the measurement in PBS group. (G) Cardiomyocytes were fixed, immunofluorescently stained for cTnT expression and TUNEL stained; nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (bar = 100 μm). (H) Apoptosis was quantified as the percentage of cells that were TUNEL-positive. (I–J) Cardiomyocytes were cultured under hypoxic conditions for 48 h in serum-free DMEM medium and treated with PBS or with exosomes collected from monolayer cultures of ECs (EC-Exo), SMCs (SMC-Exo), or cardiomyocytes (CM-Exo), from a co-culture of ECs and SMCs (EC/SMC-Exo), or from a co-culture of all three cell types (EC/SMC/CM-Exo). Cytotoxicity was evaluated via (I) measurements of cardiomyocytes LDH leakage and (J) cell viability. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. n=4–5 experiments.

When cultured with hCMP-secreted exosomes, expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 (Supplemental Figure 6A), the M-phase marker phosphorylated histone 3 (PH3) (Supplemental Figure 6B), and the cytokinesis marker Aurora B (Supplemental Figure 6C) increased significantly in hiPSC-CMs. hCMP-secreted exosomes also promoted tube formation (Supplemental Figure 7A and 7B) and migration (Supplemental Figure 7C) in cultured hiPSC-ECs. Furthermore, measurements of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage (Figure 6E), cell viability (Figure 6F), and apoptosis (Figures 6G and 6H) indicated that hCMP-secreted exosomes protected cultured cardiomyocytes from the cytotoxic effects associated with serum-free hypoxic media, but not when pretreated with inhibitors of exosome release (GW4869) or internalization (annexin V). Exosomes isolated from co-cultures of hiPSC-ECs and SMCs also protected cultured cardiomyoctes from serum-free and hypoxic injury, and exosomes obtained from all three hiPSC-derived cell types were significantly more protective than those from hiPSC-CMs alone (Figures 6I and 6J). Collectively, these observations suggest that hCMP-secreted exosomes may contribute to the beneficial effects associated with hCMP transplantation by promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation and cell-cycle activity, enhancing the neovascularization activity of endothelial cells, and protecting ischemic infarct boarder zone myocytes from apoptosis.

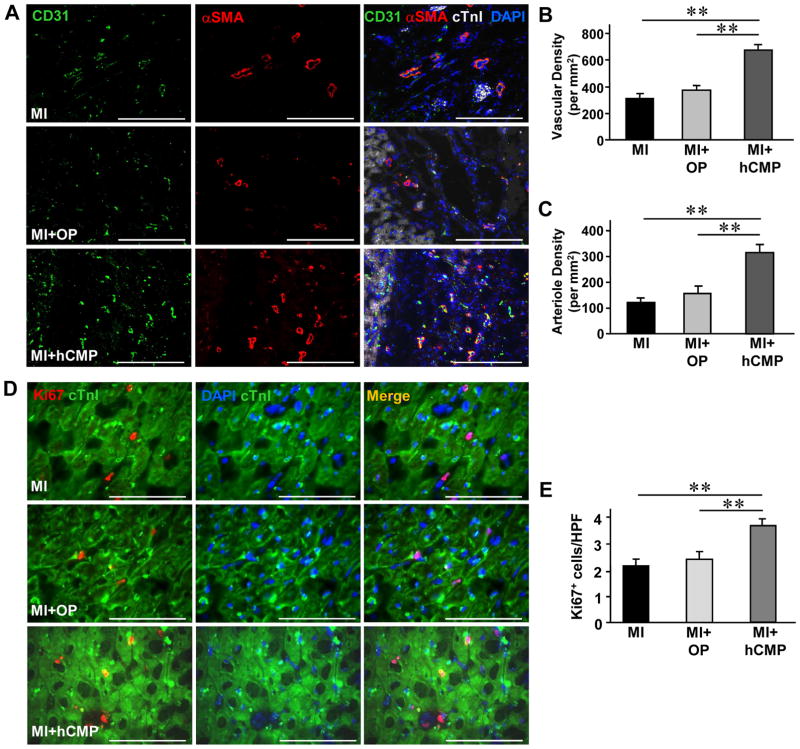

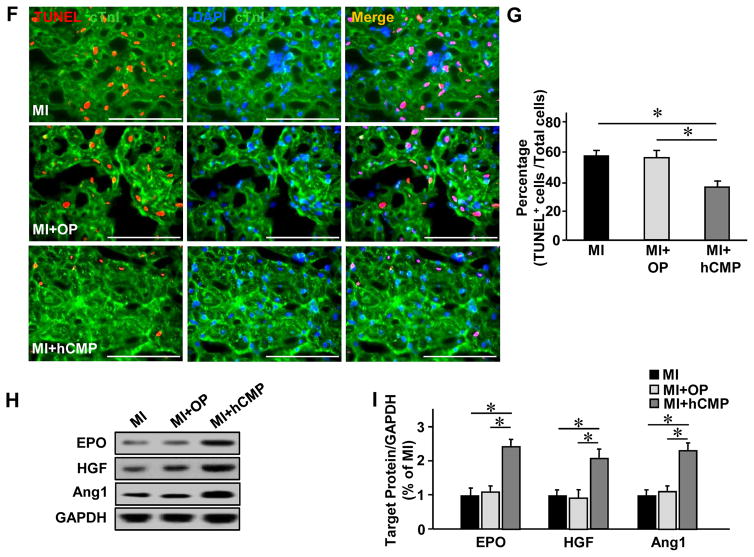

hCMP transplantation promotes angiogenesis and cell survival in the peri-scar BZ after MI

It is known that cardiomyocytes function better when there are ECs within the microenvironment. However, it remains too low (11% of 16 million cells delivered) to account for the observed improvements in LV chamber function and infarct size reduction, unless the cells promoted the activity of beneficial paracrine mechanisms. Therefore, we investigated whether hCMP transplantation may have improved the recovery of infarcted hearts by promoting the activity of mechanisms that contribute to myocardial repair and protection. The number of vascular structures either expressing CD31 (Figures 7A and 7B) or co expressing CD31 and αSMA (Figures 7A and 7C), as well as the number of cells expressing the proliferation marker Ki67 (Figures 7D and 7E), was significantly higher in the BZ of hearts from MI+hCMP animals than in the corresponding regions of hearts from MI+OP or MI animals. The BZ of hearts from hCMP-treated animals also had significantly fewer apoptotic (i.e., TUNEL-positive) cells (Figures 7F and 7G) and significantly higher levels of the pro-survival proteins erythropoietin (EPO), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and angiopoietin 1 (Ang-1) (Figures 7H and 7I). Collectively, these results suggest that the benefits of hCMP transplantation likely occurred, at least in part, through paracrine mechanisms that promote the growth of blood vessels and arterioles, as well as cell proliferation and survival.

Figure 7. hCMP transplantation enhances the vasculogenic response, promotes cell proliferation, and reduces apoptosis after MI.

Sections were collected from the border-zone of the infarct in MI, MI+OP, and MI+hCMP animals four weeks after MI induction. (A) Sections were stained with fluorescent antibodies against CD31, αSMA, and cTnI (bar = 200 μm), and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI; then, (B) vascular density was determined by quantifying the number of structures that expressed CD31, and (C) arteriole density was determined by quantifying the number of structures that expressed both CD31 and αSMA. (D) Sections were stained for expression of the cell proliferation marker Ki67, muscle fibers were visualized by fluorescent immunostaining for cTnI, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (bar = 100 μm); then, (E) cell proliferation was quantified as the number of Ki67-positive cells per high-power field (HPF) (n=6–8 per experimental group). (F) Sections taken from the border zone of infarction at week 1 after MI were stained with antibodies against cTnI, apoptotic cells were identified via a TUNEL staining, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (bar = 100 μm); then (G) apoptosis was quantified as the percentage of cells that were positive for TUNEL staining (n=3–4 in each group). (H) Expression of the prosurvival proteins erythropoietin (EPO), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and angiopoietin 1 (Ang1) at week 1 after MI were evaluated in tissues from the border zone of infarction via Western blot. Glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein levels were evaluated to serve as a control for unequal loading. (I) EPO, HGF, and Ang1 protein levels were quantified via densitometry analysis and normalized to GAPDH protein levels (n=3 in each group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

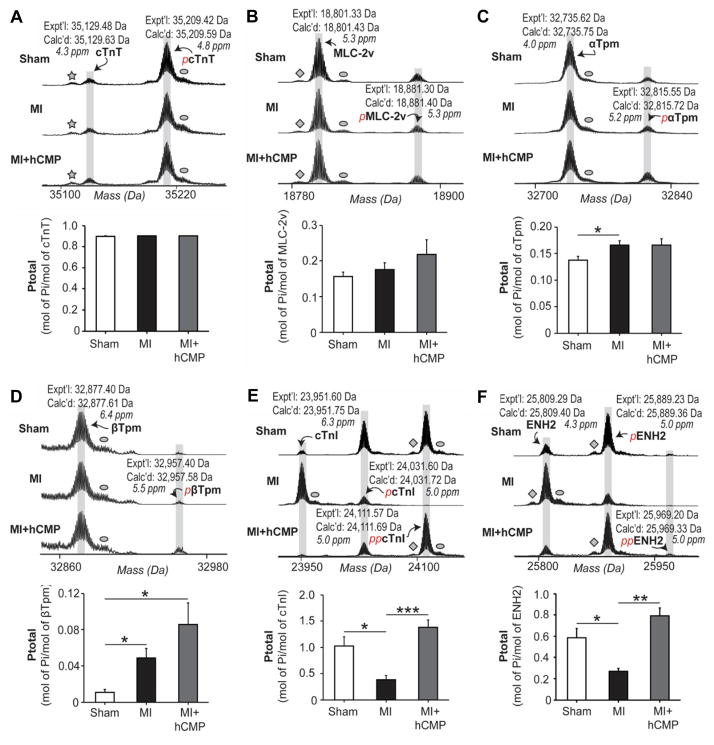

hCMP transplantation partially prevents or reverses MI-induced changes in sarcomeric protein phosphorylation

Studies have demonstrated that the phosphorylation states of sarcomeric proteins are altered by MI, and that these alterations correlate with contractile dysfunction;32, 33 thus, we conducted top-down proteomics analysis34 (Supplemental Figure 8) to determine whether the improvements in cardiac function observed in MI+hCMP animals were accompanied by the normalization of sarcomeric protein phosphorylation. cTnT (Figure 8A) and MLC-2v (Figure 8B) phosphorylation levels did not change significantly in response to MI injury or subsequent hCMP transplantation, and although α-tropomyosin (αTpm) (Figure 8C) and βTpm (Figure 8D) phosphorylation was significantly higher in MI than in Sham animals, measurements were similarly elevated in animals from the MI+hCMP group. However, measurements of cTnI (Figure 8E) and enigma homolog isoform 2 (ENH2) (Figure 8F) phosphorylation in the MI+hCMP and Sham groups were similar and significantly greater than in MI animals. Taken together, these results indicate that hCMP transplantation may prevent or reverse at least some of the changes in the phosphorylation of these key sarcomeric regulatory proteins that occur in response to MI; this previously unrecognized mechanism may be partially responsible for the improved myocardial contractility observed in hCMP-treated animals.

Figure 8. MI-induced changes in sarcomeric protein phosphorylation are partially prevented or reversed by hCMP transplantation.

Four weeks after MI induction, phosphorylation of the sarcomeric proteins (A) cTnT, (B) MLC-2v, (C) α-tropomyosin (αTpm), (D) βTpm, (E) cTnI, and (F) enigma homolog isoform 2 (ENH2), was quantified in myocardium from the border zone of infarction in animals from the MI and MI+hCMP groups and from the corresponding region of hearts in Sham animals via top-down proteomics and mass spectroscopy. Expt’l: experimentally determined most abundant molecular mass, Calc’d: calculated most abundant molecular mass based on the DNA-predicted protein sequence. The star in the cTnT/pcTnT spectrum identifies a peak caused by the loss of H3PO4, diamonds identify peaks caused by the loss of NH3, and ovals identify peaks caused by oxidation of the protein. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. n=6 per experimental group.

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first to evaluate hCMPs with trilineage cardiac cells and with clinically relevant dimensions (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm) in a large-animal model of ischemic myocardial injury. The hCMPs were cultured under dynamic (rocking) conditions for one week, which results in a prominent force generation of 1.1 nN/myocyte (Figure 3N) of the fabricated hCMP. After 7 days of dynamic culture, a superior physiological function of the novel fabricated hCMP was achieved, which is evidenced by the functional assessments of conductive velocity, calcium transients, micro-impedence, and twitch force generation. These functional data demonstrate that the mechanisms related to the intercellular communication, calcium-handling, and force-generation were significantly improved during the 7 days dynamic culture stimulation. The engraftment rate for the transplanted cells exceeded 10% at Week 4. The exosome released from the hCMP results in significant reduction of myocyte apoptosis in vitro. The treatment of novel hCMP with cardiomyocytes, ECs and SMCs was associated with significant improvements in LV wall stress, infarct size, vascular density, apoptosis, and prevented/reversed maladaptive changes in the phosphorylation states of sarcomeric proteins in BZ myocardium. The hCMP did not increase the risk of arrhythmogenic complications.

It is well-known that cardiac myocytes survive and functions much better in the microenvironment that presence of endothelial cells. In the present study, the hCMP superior functional level based on the mechanical and electrophysiological performance, is likely contributed in part by the tri lineage cardiac cell presence within the engineered tissue (Figure 2). The graft of hiPSC-derived cardiac cells can contribute directly to cardiac function, but they are also less mature than the native cardiac cells of adult hearts, which could lead to safety concerns. The gene-expression profile, as well as a variety of structural and functional properties, of hiPSC-CMs more closely resembles that of neonatal cardiomyocytes than of adult cardiomyocytes.6, 35 The abnormal calcium transients or electrophysiological properties in engrafted cardiomyocytes may cause regional variations in repolarization.28 These observations may partially explain why hPSC-cardiomyocytes, and even allogeneic monkey iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, led to incidents of spontaneous arrhythmia when studied in a nonhuman primate MI model.2, 5 Therefore, the electro-physiologically more mature hCMPs (Figure 3, Panels A–K) with the tri lineage cardiac cells under this dynamic culture condition may have better translational potential.

The cardiomyocytes present in 3D, engineered heart tissue appear to be more mature than those obtained via monolayer culturing techniques.6, 11, 16 For the experiments presented here, maturation was further promoted by rocking the hCMPs during culture and by using tri lineage cardiac that had been differentiated from cardiac-lineage hciPSCs16 (rather than hiPSCs of dermal or other lineages). Our analyses confirmed that the expression of genes involved in contraction and calcium-transient generation was significantly greater in the hCMPs than in monolayer-cultured cardiomyocytes (Supplemental Figure 2), and in hCMPs that were cultured under dynamic rather than static conditions.9 Furthermore, the conduction velocity in our hCMPs reached 14.1±1.0 cm/s that is consistent with observations from other laboratories,36 and suggests that mechanisms for gap-junction connectivity and action-potential initiation37, 38 functioned with efficiency within the structure of the novel hCMP. The enhanced electromechanical coupling of cardiomyocytes in the hCMPs was also evident from analyses of resistivity-reactivity spectra (Figure 3, Panels E–F), which suggested that intercellular gap-junction communication in the hCMPs and in native rabbit left ventricular myocardium39 was similar. Similarly, the superior functional performance of the hCMP was evidenced by the assessments of contractile force per cardiomyocyte, calcium-transient dynamics, responsiveness to a β-adrenergic agonist, the Frank-Starling mechanism,10 and the dependence of twitch force on pacing frequency and calcium concentration (Figure 3).

The porosity of the hCMP (Figure 2) likely improved the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen, which is particularly important for patches of this size, and could have improved engraftment by facilitating in-growth of angiogenesis (Figure 4, panels B–D). The unique spatial relationship of the endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes (Figure 2F & Supplemental Figure 3C) may have contributed to the superior functional characteristics the novel hCMPs of this size.

The electrophysiological activity of the hCMPs is also likely to have been influenced by the inclusion of hiPSC-SMCs and -ECs in the hCMP. Endothelial cells have been shown to improve recovery from myocardial injury, regulate cardiovascular physiology, and promote the survival of transplanted cardiomyocytes primarily by activating cytokine-associated mechanisms. The results from experiments in our laboratory indicate that cardiomyocytes are more resistant to hypoxia-induced apoptosis and LDH leakage when cultured with EC- and SMC-conditioned medium.3 Furthermore, the data presented here suggest that at least some of the cytoprotective effects associated with ECs and SMCs are mediated by exosome release (Figure 6), and the exosomes may also carry paracrine factors that contributed to the observed increases in angiogenesis and native cardiomyocyte proliferation. Collectively, these paracrine mechanisms, as well as the microenvironment of the patch itself, likely contributed to the relatively high engraftment rate (10.9±1.8%), which is consistent with the results from studies in rodents.4, 11, 15

Our top-down proteomics analyses confirmed that four weeks after MI injury, phosphorylation of the sarcomeric proteins ENH2 and cTnI was significantly reduced in animals from the MI group, which is consistent with the results from previous studies,32, 33 and that these reductions were prevented (or reversed) in MI+hCMP animals. The hCMP-associated increase in cTnI phosphorylation may be particularly relevant, because reports from other groups indicate that declines in cTnI phosphorylation can contribute to contractile dysfunction after MI or during end-stage heart failure by increasing myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity.33, 40 Thus, these results are the first to suggest that hiPSC-derived cardiac cells may improve contractile function in infarcted hearts by preventing or reversing maladaptive changes in the phosphorylation states of sarcomeric proteins.

Conclusion

The experiments presented in this report are the first to evaluate a novel type of hCMP of clinically relevant dimensions (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm) in a large-animal model of ischemic myocardial injury. In vitro assessments indicated that the machinery required for calcium-handling and force-generation of cardiomyocytes within the hCMP was relatively well-developed in response to the dynamic culture stimulation for 7 days. When tested in a porcine MI model, the engraftment rate for the transplanted cells exceeded 10% at week 4, and the treatment was associated with improvements in LV dilatation, wall stress, infarct size, and preventing/reversing maladaptive changes in the phosphorylation states of sarcomeric proteins in BZ myocardium. The hCMP therapy did not increase the risk of arrhythmia.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What Is New?

Human cardiac muscle patches (hCMPs) of clinically relevant dimensions (4 cm × 2 cm × 1.25 mm) were generated by suspending cardiomyocytes, smooth-muscle cells, and endothelial cells that had been differentiated from human induced-pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) in a fibrin matrix and culturing the construct on a dynamic (rocking) platform.

The results from in-vitro assessments of calcium transients, action potential propagation, and force generation, as well as the presence of intercalated disk-like structures, suggest that cardiomyocytes maturing in the hCMP during the 7-day dynamic culture period.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

We present hCMPs with larger dimensions.

After fabrication and culture on a dynamic, rocking platform, the electrophysiological and contractile properties of the hCMPs resembled those of native myocardial tissue.

When two of the hCMPs were transplanted onto infarcted swine heart. measurements of cardiac function, infarct size, wall stresses improved significantly with no increase in the occurrence of arrhythmogenic complications. Changes in the expression profile of myocardial proteins indicated that hCMP transplantation partially reversed abnormalities in sarcomeric protein phosphorylation.

Collectively, these observations indicate that hCMPs of clinically relevant dimensions can be successfully generated and may improve recovery from ischemic myocardial injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. W. Kevin Cukier-Meisner for his editorial assistance with the completion of this manuscript, and Dr. Yanwen Liu for excellent technical assistance.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the following funding sources: NIH RO1 HL 99507, HL114120, HL 131017, UO1 HL134764 (to J.Z.), NIH F31 HL128086 (to Z.R.G.), and Shared Instrumentation Grant (SIG) Program OD018475, NIH R01 HL 109810 (to Y.G.)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Sayed N, Liu C, Wu JC. Translation of Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From Clinical Trial in a Dish to Precision Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2161–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiba Y, Gomibuchi T, Seto T, Wada Y, Ichimura H, Tanaka Y, Ogasawara T, Okada K, Shiba N, Sakamoto K, Ido D, Shiina T, Ohkura M, Nakai J, Uno N, Kazuki Y, Oshimura M, Minami I, Ikeda U. Allogeneic transplantation of iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerates primate hearts. Nature. 2016;538:388–391. doi: 10.1038/nature19815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye L, Chang YH, Xiong Q, Zhang P, Zhang L, Somasundaram P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Su L, Wendel JS, Guo J, Jang A, Rosenbush D, Greder L, Dutton JR, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Kaufman DS, Ge Y, Zhang J. Cardiac repair in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiovascular cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:750–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riegler J, Tiburcy M, Ebert A, Tzatzalos E, Raaz U, Abilez OJ, Shen Q, Kooreman NG, Neofytou E, Chen VC, Wang M, Meyer T, Tsao PS, Connolly AJ, Couture LA, Gold JD, Zimmermann WH, Wu JC. Human Engineered Heart Muscles Engraft and Survive Long Term in a Rodent Myocardial Infarction Model. Circulation research. 2015;117:720–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong JJ, Yang X, Don CW, Minami E, Liu YW, Weyers JJ, Mahoney WM, Van Biber B, Cook SM, Palpant NJ, Gantz JA, Fugate JA, Muskheli V, Gough GM, Vogel KW, Astley CA, Hotchkiss CE, Baldessari A, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Gill EA, Nelson V, Kiem HP, Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature. 2014;510:273–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun X, Nunes SS. Bioengineering Approaches to Mature Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2017;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2017.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson C, Tran DD, George SC. Concise review: maturation phases of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem cells. 2013;31:829–37. doi: 10.1002/stem.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiburcy M, Hudson JE, Balfanz P, Schlick S, Meyer T, Chang Liao ML, Levent E, Raad F, Zeidler S, Wingender E, Riegler J, Wang M, Gold JD, Kehat I, Wettwer E, Ravens U, Dierickx P, van Laake LW, Goumans MJ, Khadjeh S, Toischer K, Hasenfuss G, Couture LA, Unger A, Linke WA, Araki T, Neel B, Keller G, Gepstein L, Wu JC, Zimmermann WH. Defined Engineered Human Myocardium With Advanced Maturation for Applications in Heart Failure Modeling and Repair. Circulation. 2017;135:1832–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackman CP, Carlson AL, Bursac N. Dynamic culture yields engineered myocardium with near-adult functional output. Biomaterials. 2016;111:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruan JL, Tulloch NL, Razumova MV, Saiget M, Muskheli V, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Regnier M, Murry CE. Mechanical Stress Conditioning and Electrical Stimulation Promote Contractility and Force Maturation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Human Cardiac Tissue. Circulation. 2016;134:1557–1567. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao L, Kupfer ME, Jung JP, Yang L, Zhang P, Da Sie Y, Tran Q, Ajeti V, Freeman BT, Fast VG, Campagnola PJ, Ogle BM, Zhang J. Myocardial Tissue Engineering With Cells Derived From Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and a Native-Like, High-Resolution, 3-Dimensionally Printed Scaffold. Circulation research. 2017;120:1318–1325. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogle BM, Bursac N, Domian I, Huang NF, Menasche P, Murry CE, Pruitt B, Radisic M, Wu JC, Wu SM, Zhang J, Zimmermann WH, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Distilling complexity to advance cardiac tissue engineering. Science translational medicine. 2016;8:342ps13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen PK, Neofytou E, Rhee JW, Wu JC. Potential Strategies to Address the Major Clinical Barriers Facing Stem Cell Regenerative Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:953–962. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzatzalos E, Abilez OJ, Shukla P, Wu JC. Engineered heart tissues and induced pluripotent stem cells: Macro- and microstructures for disease modeling, drug screening, and translational studies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;96:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger F, Breckwoldt K, Pecha S, Kelly A, Geertz B, Starbatty J, Yorgan T, Cheng KH, Lessmann K, Stolen T, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Smith G, Reichenspurner H, Hansen A, Eschenhagen T. Cardiac repair in guinea pigs with human engineered heart tissue from induced pluripotent stem cells. Science translational medicine. 2016;8:363ra148. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang D, Shadrin IY, Lam J, Xian HQ, Snodgrass HR, Bursac N. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Guo J, Zhang P, Xiong Q, Wu SC, Xia L, Roy SS, Tolar J, O’Connell TD, Kyba M, Liao K, Zhang J. Derivation and high engraftment of patient-specific cardiomyocyte sheet using induced pluripotent stem cells generated from adult cardiac fibroblast. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:156–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lux M, Andree B, Horvath T, Nosko A, Manikowski D, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Haverich A, Hilfiker A. In vitro maturation of large-scale cardiac patches based on a perfusable starter matrix by cyclic mechanical stimulation. Acta Biomater. 2016;30:177–87. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye L, Zimmermann WH, Garry DJ, Zhang J. Patching the heart: cardiac repair from within and outside. Circulation research. 2013;113:922–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Zhang L, Kaufman DS, Zhang J. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of cellular therapy: activation of endogenous cardiovascular progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2012;111:455–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling Gao. Large Cardiac-muscle Patches [Internet] 2017 Available from: osf.io/hrzjb.

- 22.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, Lan F, Diecke S, Huber B, Mordwinkin NM, Plews JR, Abilez OJ, Cui B, Gold JD, Wu JC. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2014;11:855–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:162–75. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S, Dutton JR, Su L, Zhang J, Ye L. The influence of a spatiotemporal 3D environment on endothelial cell differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:3786–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sequeira V, van der Velden J. Historical perspective on heart function: the Frank-Starling Law. Biophysical reviews. 2015;7:421–447. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendel JS, Ye L, Tao R, Zhang J, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Tranquillo RT. Functional Effects of a Tissue-Engineered Cardiac Patch From Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes in a Rat Infarct Model. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1324–32. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Huang W, Liu G, Cai W, Millard RW, Wang Y, Chang J, Peng T, Fan GC. Cardiomyocytes mediate anti-angiogenesis in type 2 diabetic rats through the exosomal transfer of miR-320 into endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;74:139–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson ME, Goldhaber J, Houser SR, Puceat M, Sussman MA. Embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes are not ready for human trials. Circ Res. 2014;115:335–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung JH, Fu X, Yang PC. Exosomes Generated From iPSC-Derivatives: New Direction for Stem Cell Therapy in Human Heart Diseases. Circulation research. 2017;120:407–417. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waldenstrom A, Ronquist G. Role of exosomes in myocardial remodeling. Circulation research. 2014;114:315–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Liu K, Liu Y, Xu Y, Zhang F, Yang H, Liu J, Pan T, Chen J, Wu M, Zhou X, Yuan Z. Exosomes mediate the cell-to-cell transmission of IFN-alpha-induced antiviral activity. Nature immunology. 2013;14:793–803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Y, Gregorich ZR, Valeja SG, Zhang H, Cai W, Chen YC, Guner H, Chen AJ, Schwahn DJ, Hacker TA, Liu X, Ge Y. Top-down proteomics reveals concerted reductions in myofilament and Z-disc protein phosphorylation after acute myocardial infarction. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2752–64. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.040675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Velden J, Merkus D, Klarenbeek BR, James AT, Boontje NM, Dekkers DH, Stienen GJ, Lamers JM, Duncker DJ. Alterations in myofilament function contribute to left ventricular dysfunction in pigs early after myocardial infarction. Circulation research. 2004;95:e85–95. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000149531.02904.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai W, Tucholski TM, Gregorich ZR, Ge Y. Top-down Proteomics: Technology Advancements and Applications to Heart Diseases. Expert review of proteomics. 2016;13:717–30. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2016.1209414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang X, Pabon L, Murry CE. Engineering adolescence: maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circulation research. 2014;114:511–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackman CP, Shadrin IY, Carlson AL, Bursac N. Human Cardiac Tissue Engineering: From Pluripotent Stem Cells to Heart Repair. Curr Opin Chem Eng. 2015;7:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herron TJ, Lee P, Jalife J. Optical imaging of voltage and calcium in cardiac cells & tissues. Circulation research. 2012;110:609–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong W, Fakhari N, Sharifov OF, Ideker RE, Smith WM, Fast VG. Optical measurements of intramural action potentials in isolated porcine hearts using optrodes. Heart rhythm: the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2007;4:1430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waits CM, Barr RC, Pollard AE. Sensor spacing affects the tissue impedance spectra of rabbit ventricular epicardium. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2014;306:H1660–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00661.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB. Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: dephosphorylation of Ser23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:247–59. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.