Abstract

Background

Oral oxybutynin has been associated with the development of cognitive impairment.

Objective

The objective of this study was to describe the use of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics (e.g., tolterodine, darifenacin, solifenacin, trospium, fesoterodine, transdermal oxybutynin) in older adults with documented cognitive impairment.

Methods

This is a population-based retrospective analysis of antimuscarinic new-users aged 66 years or older from 1/2008 to 12/2011 (n=42,886) using 5% random sample of Medicare claims linked with Part D data. Cognitive impairment was defined as a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, antidementia medication, and memory loss/drug-induced cognitive conditions in the year prior to the initial antimuscarinic claim. We used multivariable generalized linear models to assess indicators of cognitive impairment associated with initiation of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics after adjusting for comorbid conditions.

Results

Thirty-three percent received oral oxybutynin as initial therapy. Documented cognitive impairment was present in 10,259 (23.9%) patients prior to antimuscarinic therapy. Patients with cognitive impairment were 5% more likely to initiate another antimuscarinic versus oral oxybutynin (RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.06). The proportion of patients with cognitive impairment initiated on oral oxybutynin increased from 24.1% in 2008 to 41.1% in 2011. The total cost in $2011 of oral oxybutynin decreased by 10.5% whereas total cost of other antimuscarinics increased by 50.3% from 2008 to 2011.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest opportunities for quality improvement of antimuscarinic prescribing in older adults, but may be hampered by cost and formulary restrictions.

1 Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a condition that can negatively impact quality of life in older adults. The prevalence of OAB increases with age, with signs and symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, and incontinence which affects up to 25% of adults aged 60 or older.1–5 After non-pharmacological options have failed, the standard treatment for OAB is an antimuscarinic agent or a beta-3 agonist (e.g., mirabegron). In general, various agents have similar efficacy in improving OAB symptoms.6 However, certain antimuscarinics may cause drug-associated cognitive impairment due to their ability to pass through the blood brain barrier (e.g., lipophilicity, molecular size, and molecular charge) and block muscarinic-1 receptors (i.e., the receptor responsible for causing cognitive impairment).4 Overall, oxybutynin is the most lipophilic antimuscarinic, has the lowest molecular weight, and blocks muscarinic-1 receptors along with muscarinic-3 receptors.4,7–9 This is in contrast to darifenacin which was developed to avoid certain adverse events like cognitive impairment.10 Compared to oxybutynin, darifenacin is less lipophilic, has a higher molecular weight, and is much more selective to muscarinic-3 receptors (i.e., the receptor responsible for improving OAB symptoms).4,7–9 Eight small prospective studies purport that certain antimuscarinics are associated with an increased risk for worsened cognitive impairment while other have not been associated with this risk.11–18 Three studies assessed cognition at baseline and after medication exposure for oral oxybutynin immediate-release (IR) and oral oxybutynin extended-release (ER) along with comparator agents (e.g., placebo, oxybutynin transdermal, solifenacin, darifenacin) baseline cognition relative to cognition after was associated with significantly worsened cognition.11–13 Significantly worsened cognition was identified in patients who received oral oxybutynin IR or oral oxybutynin ER while no change in cognition was identified in patients who received comparator agents using several different instruments to measure cognition.11–13 However, two studies that assessed cognition at baseline and after medication exposure for oral oxybutynin extended-release (ER) showed no worsened cognition.17,18 These studies were limited by relatively small sample size.17,18 The other antimuscarinics (e.g., tolterodine, darifenacin, solifenacin, trospium, fesoterodine, transdermal oxybutynin) did not carry the risk for worsened cognition.11–16

Knowledge of the risk profile of these medications that have similar therapeutic benefits but varying degrees of risk for drug-associated cognitive impairment could lead to differential prescribing of antimuscarinics by providers. Specifically, older adults with cognitive impairment can be preferentially prescribed other antimuscarinics or mirabegron instead of oral oxybutynin in order to avoid the risk of worsening cognitive impairment when OAB treatment is warranted.11–16,19 However, other antimuscarinics and mirabegron may not be readily available to patients due to formulary restrictions and increased co-payment costs which may lead to the use oral oxybutynin in patients with cognitive impairment or the avoidance of treatment in patients with OAB.20 Understanding the association between cognitive impairment and costs on the differential prescribing of antimuscarinics may lead to a better understanding of prescribing behavior in the use of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics. The aim of this study was to evaluate factors suggestive of documented cognitive impairment on the prescribing of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics in a general population of older adults.

2 Methods

We performed a population-based retrospective analysis of older adults in the United States with at least one filled prescription for an antimuscarinic between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011 using the 5% random sample longitudinal Medicare claims data from the Chronic Condition Warehouse linked with Part D Prescription Drug Event data. Mirabegron was not included because it was not approved during the study period. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine with a waiver of informed consent.

2.1 Study Population

All patients aged 66 years and older with at least 12 months of baseline data and complete Medicare Part A (hospital), Part B (physician and outpatient facility), and Part D (prescription drug) coverage prior to the first paid antimuscarinic claim were included. Patients enrolled in an HMO (Health Maintenance Organization) were excluded due to incomplete claims data.

Antimuscarinics were identified in the Part D Prescription Drug Event data: oxybutynin, tolterodine, trospium, solifenacin, darifenacin, and fesoterodine. Oral versus transdermal medications and IR versus ER formulations were differentiated. A new-user design was incorporated to include patients who had at least 12 months of coverage prior to their first antimuscarinic claim.21 Patients were required to have at least one claim for a medication other than an antimuscarinic within 12 months before the first antimuscarinic claim to confirm prescription drug coverage use. Patients who filled two or more different antimuscarinics on the date of the first antimuscarinic claim were excluded (n=44).

2.2 Definitions of Antimuscarinic Types

Other antimuscarinics included transdermal oxybutynin (patch or gel), tolterodine IR or ER, trospium IR or ER, solifenacin, darifenacin, and fesoterodine. Oral oxybutynin included both oxybutynin IR (tablet and liquid) and oxybutynin ER (tablet).

2.3 Primary Exposure

We hypothesized that documented cognitive impairment through ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for dementia22, or memory loss/drug-induced cognitive conditions or use of antidementia medications (e.g., acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine) would result in differential prescribing of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics. Cognitive impairment was defined as the composite of mild cognitive impairment diagnosis, dementia diagnosis, memory loss/drug-induced cognitive conditions diagnosis,23 or treatment with an antidementia medication (Appendix 1).

2.4 Factors Potentially Associated with Differential Prescribing of Antimuscarinics

Differential prescribing of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics on the basis of documented cognitive impairment may also be confounded by comorbid conditions and medications; therefore, several comorbidities were examined using the Elixhauser Comorbidity algorithm,24 modified to include medications used to treat hypertension, diabetes, and hypothyroidism. Other comorbid conditions diagnosed in the older adults or comorbid conditions that may be associated with cognitive impairment, along with medications used to treat these conditions (e.g., osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, glaucoma, high cholesterol, constipation, weakness, falls) were also included. We also assessed medications that may contribute to differential prescribing of antimuscarinics, including antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and controlled prescriptions used to treat insomnia as providers who prescribed these potentially inappropriate medications in older adults may also be more likely to prescribe oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics.25 Patient characteristics, year of the initial antimuscarinic claim, hospitalization in the previous 12 months, and clinic visits to specialist providers (e.g., geriatrician, urologist, neurologist) within 30 days before the first antimuscarinic claim were explored as factors that may influence differential prescribing.26 All ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and names of medications used to identify factors of differential prescribing are listed in Appendix 1. Potential factors associated with differential prescribing were collected in the 12 months prior to the first antimuscarinic claim, henceforth referred to as the baseline period.27 One or two outpatient claims (one claim for acute comorbidities and two claims at least 30 days apart for chronic comorbidities), one inpatient claim, or one medication claim (if specified) were required during the baseline period to be considered as a potential factor for differential prescribing.

2.5 Potential Prescribing Cascade

A prescribing cascade occurs when an adverse event of a medication results in the prescription of a new, potentially unnecessary medication, instead of discontinuing the initial medication.28 The prescribing cascade that results in initiation of an antimuscarinic in patients treated with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) has been previously described by Gill and colleagues.28,29 Increased urinary symptoms attributable to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors occurred in 4–7% of treated persons,29–31 but are typically transient.30,32 Therefore, we assessed the proportion of patients with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor in the baseline period who initiated or dose-escalated the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor within the three months prior to antimuscarinic initiation to further explore the potential for this prescribing cascade.

2.6 Influence of Costs

We explored the influence of medication costs, which likely changed over the included years, on antimuscarinic selection in a post-hoc analysis. We assessed the median total prescription costs standardized to a 30 day supply. Total prescription costs included the ingredient cost, dispensing fee, and sales tax (when applicable). Costs were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index for Prescription Drugs standardized to 2011 dollars.33

2.7 Statistical Analyses

Factors during the baseline period that were potentially associated with differential prescribing were compared using descriptive and inferential statistics. Differences between oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics in documented cognitive impairment were reported using relative risks (RR) and p-values. Relative risks were utilized instead of odds ratio due to the violation of the rare disease assumption.34 The differences in cognitive impairment by year (i.e., interaction) was assessed to evaluate trends of differential prescribing during the study period.

Factors associated with differential prescribing of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics were explored using generalized linear models with Proc GENMOD. Generalized linear models were used to calculate relative risks in multivariable analysis.35 Factors, including the interaction with year, with a p-value <0.1 were included in the initial multivariable generalized linear models, with removal of variables using backward selection. Collinearity was not identified using variance inflation factors. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1. (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

From 2008 to 2011, 42,886 patients filled a prescription for an antimuscarinic. Patients were not required to have a diagnosis of OAB (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes 596.51; 596.59; 788.1×; 788.3×) as it was likely under-coded as only 38% of patients were coded for OAB in the previous 12 months.

Sixty-seven percent of patients received other antimuscarinics (e.g., tolterodine, trospium, darifenacin, solifenacin, and transdermal oxybutynin) as initial therapy (n=28,736). Among those who initiated on an antimuscarinic, the proportion of patients treated with oral oxybutynin increased from 24.6% in 2008 to 45.2% in 2011. The most common antimuscarinic used as initial therapy was tolterodine ER, which comprised 29.6% of all initial antimuscarinic agents (Table 1). Oxybutynin IR, solifenacin, oxybutynin ER, and darifenacin were the next most commonly utilized initial antimuscarinic which comprised 20.7%, 18.4%, 12.3%, and 9.6% of agents identified.

Table 1.

Initiation of Individual Antimuscarinic Agents in the Population of Older Adults and in Individuals with Baseline Cognitive Impairment

| Antimuscarinic Agents (n=42,886) Row – n (%) |

No Cognitive Impairmentb (n=32,627) |

Cognitive Impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Cognitive Impairmentc (n=10,259) |

Dementia (n=6,340) |

Any Antidementia Medicationd (n=4,791) |

Drug-Induced Cognitive Impairment / Memory Loss (n=5,441) |

|||

| Oral Oxybutynin 14,150 (33.0) | Oxybutynin IRa (n=8,888) | 6,956 (78.3) | 1,932 (21.7) | 1,171 (13.2) | 833 (9.4) | 1,090 (12.8) |

| Oxybutynin ER (n=5,262) | 4,054 (77.0) | 1,208 (23.0) | 735 (14.0) | 522 (9.9) | 665 (12.6) | |

| Other Antimuscarinics 28,736 (67.0) | Tolterodine IR (n=1,393) | 983 (70.6) | 410 (29.4) | 262 (18.8) | 163 (11.7) | 235 (16.9) |

| Tolterodine ER (n=12,688) | 9,555 (75.3) | 3,133 (24.7) | 1,976 (15.6) | 1,485 (11.7) | 1,610 (12.7) | |

| Oxybutynin patch (n=611) | 356 (58.3) | 255 (41.7) | 200 (32.7) | 125 (20.5) | 116 (19.0) | |

| Oxybutynin gel (n=243) | 201 (82.7) | 42 (17.3) | 21 (8.6) | 20 (8.2) | 26 (10.7) | |

| Trospium IR (n=303) | 209 (69.0) | 94 (31.0) | 57 (18.8) | 44 (14.5) | 51 (16.8) | |

| Trospium ER (n=949) | 715 (75.4) | 234 (24.7) | 128 (13.5) | 126 (13.3) | 139 (14.7) | |

| Solifenacin (n=7,906) | 6,109 (77.3) | 1,797 (22.7) | 1,074 (13.6) | 870 (11.0) | 938 (11.9) | |

| Darifenacin (n=4,131) | 3,103 (75.1) | 1,028 (24.9) | 643 (15.6) | 546 (11.0) | 502 (12.2) | |

| Fesoterodine (n=512) | 386 (75.4) | 126 (24.6) | 73 (14.3) | 57 (11.1) | 69 (13.5) | |

Count comprises Oxybutynin IR (n=8,843) and Oxybutynin liquid (n=45)

No Diagnosis of Dementia, diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment, any antidementia medication, or Drug-Induced Cognitive Impairment / Memory Loss

Diagnosis of Dementia, diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment, any antidementia medication, or Drug-Induced Cognitive Impairment / Memory Loss

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) or memantine

3.1 Cognitive Impairment and Potential Prescribing Cascade

Overall, 23.9% (n=10,259) of patients who initiated on an antimuscarinic had documented cognitive impairment prior to antimuscarinic initiation (Table 1). Among those initiated on an antimuscarinic, 14.8% (n=6,340) of patients had at least one diagnosis code for dementia, 11.2% (n=4,791) of patients had at least one claim for an antidementia medication, and 12.9% (n=5,441) of patients were coded for memory loss/drug-induced cognitive conditions during the baseline period. Among the patients who received an antidementia medication, 27.7% were not coded for dementia during the baseline period (n=1,326). Among patients with cognitive impairment, 30.6% (n=3,140) were initiated on oral oxybutynin and 69.4% (n=7,119) were initiated on another antimuscarinic. Among patients with no cognitive impairment, 33.7% (n=11,010) were initiated on oral oxybutynin and 66.3% (n=21,617) were initiated on another antimuscarinic (Appendix 2).

In patients who initiated on oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics, 8.6% (n=1,211) and 10.8% (n=3,097), respectively, were prescribed an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor during the baseline period. Among patients with at least one claim for an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor during the baseline period, a potential prescribing cascade (e.g., initiation or escalation of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor in the three months) occurred in 14.4% (n=174) and 15.1% (n=67) of patients prior to initiation of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinic, respectively.

3.2 Univariate Analyses

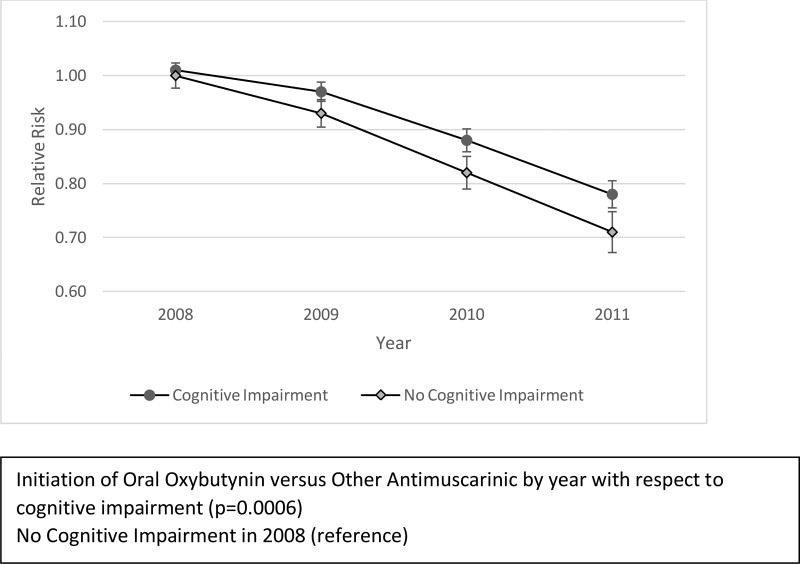

In univariate analyses several baseline characteristics were associated with the initiation of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics (Table 2). Patients with cognitive impairment were 5% more likely to be initiated on another antimuscarinic (RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.06). Oral oxybutynin was prescribed less frequently in the early years of the study, with progressively greater use over time. Initiation of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics also differed significantly by year with respect to cognitive impairment (p=0.0006) (Figure 1). In 2008, patients with cognitive impairment were equally likely to be initiated on another antimuscarinic compared to patients without cognitive impairment; by 2011 the relative risk difference was 7%. Compared to 2008, patients with cognitive impairment were 23% less likely to be initiated on another antimuscarinic in 2011.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Potential Factors Associated with Differential Prescribing in the Baseline Period

| Variablesa | Other Antimuscarinics (n=28,736) n (%) |

Oral Oxybutynin (n=14,150) n (%) |

Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Demographic Information | Age – median (IQR) | 79 (73–85) | 78 (72–84) | 1.003 (1.003–1.004) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Age (years) | <0.0001 | ||||

| <75 | 9,524 (33.1) | 5,150 (36.4) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 75 – 84 | 11,961 (41.6) | 5,777 (40.8) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | ||

| ≥85 | 7,251 (25.2) | 3,223 (22.8) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | ||

|

| |||||

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||||

| Female | 22,017 (76.6) | 10,200 (72.1) | 1.09 (1.07–1.10) | ||

|

| |||||

| Region | <0.0001 | ||||

| Northeast | 5,207 (18.1) | 2,107 (14.9) | 1.14 (1.11–1.16) | ||

| Midwest | 6,973 (24.3) | 4,153 (29.4) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| South | 11,970 (41.7) | 5,219 (36.9) | 1.11 (1.09–1.13) | ||

| West | 4,531 (15.8) | 2,651 (18.7) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | ||

| Other | 55 (0.2) | 20 (0.1) | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) | ||

|

| |||||

| Year | <0.0001 | ||||

| 2008 | 9,570 (33.3) | 3,129 (22.1) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 2009 | 8,109 (28.2) | 3,385 (23.9) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | ||

| 2010 | 6,266 (21.8) | 3,682 (26.0) | 0.84 (0.82–0.85) | ||

| 2011 | 4,791 (16.7) | 3,954 (27.9) | 0.73 (0.71–0.74) | ||

|

| |||||

| Median Household Income for Zip Code ($), 2011b | <0.0001 | ||||

| <40,000 | 7,390 (25.7) | 3,707 (26.2) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 40,000 to 48,999 | 6,688 (23.3) | 3,558 (25.1) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | ||

| 49,000 to 63,999 | 6,821 (23.7) | 3,475 (24.6) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | ||

| ≥64,000 | 7,312 (25.5) | 3,190 (22.5) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | ||

| Missing | 525 (1.8) | 220 (1.6) | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | ||

|

| |||||

| Comorbidities | Cancer | 3,169 (11.0) | 1,735 (12.3) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.0002 |

|

| |||||

| Deficiency anemias | 5,406 (18.8) | 2,410 (17.0) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Epilepsy / Seizure | 580 (2.0) | 269 (1.9) | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 0.0875 | |

|

| |||||

| Glaucoma | 3,397 (11.8) | 1,537 (10.9) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.0027 | |

|

| |||||

| High Cholesterol | 17,100 (59.5) | 8,203 (58.0) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.0025 | |

|

| |||||

| Hypothyroidism | 7,078 (24.6) | 3,275 (23.1) | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.0006 | |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | 23,879 (83.1) | 11,635 (82.2) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.0264 | |

|

| |||||

| Malaise / Fatigue | 9,335 (2.5) | 4,301 (30.4) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Neurological disorders | 3,504 (12.2) | 1,547 (10.9) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Osteoarthritis | 10,792 (37.6) | 4,896 (34.6) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Osteoporosis | 5,987 (20.8) | 2,364 (16.7) | 1.09 (1.07–1.11) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Parkinson’s disease | 1,784 (6.2) | 773 (5.5) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | 0.0014 | |

|

| |||||

| Blood loss anemia | 355 (1.2) | 150 (1.1) | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.0956 | |

|

| |||||

| Renal Failure | 2,150 (7.5) | 1,171 (8.3) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.0050 | |

|

| |||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagenvascular diseases | 1,365 (4.8) | 596 (4.2) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.0091 | |

|

| |||||

| Sleep Apnea | 533 (1.9) | 299 (2.1) | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.0804 | |

|

| |||||

| Vertigo | 4,801 (16.7) | 2,063 (14.6) | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Rehabilitation Services | 1,222 (4.3) | 553 (3.9) | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.0836 | |

|

| |||||

| Stroke | 1,078 (3.8) | 480 (3.4) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.0534 | |

|

| |||||

| Medications | Sleep Medication | 4,660 (16.2) | 2,042 (14.4) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Cognitive Impairment | Dementia diagnosis | 4,434 (15.4) | 1,906 (13.5) | 1.06 (1.03–1.07) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor | 3,097 (10.8) | 1,211 (8.6) | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Memantine | 1,357 (4.7) | 526 (3.7) | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Any Dementia Medication | 3,436 (12.0) | 1,355 (9.6) | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| All Cognitive Impairment | 7,119 (24.8) | 3,140 (22.2) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Provider Types | Neurology / Neuropsychiatry | 1,099 (3.8) | 482 (3.4) | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.0248 |

|

| |||||

| Urology | 7,806 (27.2) | 4,013 (28.4) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.0098 | |

Variables with P-Value ≥ 0.1: Demographic Information (Race); Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (Congestive heart failure, Paralysis, Chronic pulmonary disease, Diabetes Mellitus, Depression); Other Comorbidities (Aspiration Pneumonia, Cardiovascular Disease, Constipation, Delirium, Dysphagia, Falls, Skin Ulcer, Syncope, Traumatic Brain Injury, Weakness), Medications (Benzodiazepine, Stimulant Medication), Variables Associated with Cognitive Impairment (Mild cognitive impairment, Memory Loss / Drug-Induced Cognitive Conditions), Provider Types (Geriatrics), Hospitalizations (Hospitalized during Baseline Period)

2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – Median Household Income in the Past 12 Month (in 2011 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars)

Composite of diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment diagnosis, or dementia diagnosis, treatment with an antidementia medication, or memory loss / drug-induced cognitive conditions (Appendix 1)

IQR = Interquartile Range

Figure 1.

Univariate Analysis of the Interaction of Other Antimuscarinic Use Relative to Oral Oxybutynin by Year with Respect to Cognitive Impairment

3.3 Multivariable Analysis

In multivariable analysis, patients with cognitive impairment were progressively less likely to initiate treatment with another antimuscarinic over time after controlling for age, sex, geographic location, ZIP code median household income, high cholesterol, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, renal failure, vertigo, and the use of sleep medications (Table 3). Patients without evidence of cognitive impairment were also progressively less likely to initiate treatment with another antimuscarinic over time relative to 2008, and less likely than patients with cognitive impairment to initiate with another antimuscarinic agent after controlling for other variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Initiating Another Antimuscarinic Versus Oral Oxybutynin, 2008–2011.

| Variablesa | Relative Risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographic Information | Age (years) | |

| <75 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 75 – 84 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | |

| ≥85 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | |

|

| ||

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 1.10 (1.08–1.13) | |

| Midwest | 1.00 (reference) | |

| South | 1.10 (1.09–1.12) | |

| West | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | |

| Other | 1.19 (1.05–1.34) | |

|

| ||

| Median Household Income for Zip Code ($), 2011b | ||

| <40,000 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 40,000 to 48,999 | 0.99 (0.98–1.02) | |

| 49,000 to 63,999 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | |

| ≥64,000 | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | |

| Missing | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | |

|

| ||

| Comorbidities | High Cholesterol | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) |

|

| ||

| Osteoarthritis | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | |

|

| ||

| Osteoporosis | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | |

|

| ||

| Renal Failure | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | |

|

| ||

| Vertigo | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | |

|

| ||

| Medications | Sleep Medications | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) |

|

| ||

| Cognitive Impairment per Year | No Cognitive Impairment – 2008 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Cognitive Impairment – 2008 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | |

| No Cognitive Impairment – 2009 | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) | |

| Cognitive Impairment – 2009 | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) | |

| No Cognitive Impairment – 2010 | 0.83 (0.81–0.85) | |

| Cognitive Impairment – 2010 | 0.87 (0.85–0.90) | |

| No Cognitive Impairment – 2011 | 0.72 (0.70–0.74) | |

| Cognitive Impairment – 2011 | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | |

Variables removed from the model: Antipsychotic Medication, Blood loss anemia, Cancer, Deficiency anemias, Epilepsy/Seizure, Glaucoma, Hypertension, Hypothyroidism, Malaise / Fatigue, Neurological disorders, Parkinson’s Disease Rehabilitation Services, Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases, Sleep apnea, Stroke, Visit to Neurology / Neuropsychiatry, Visit to Urology

2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates – Median Household Income in the Past 12 Month (in 2011 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars)

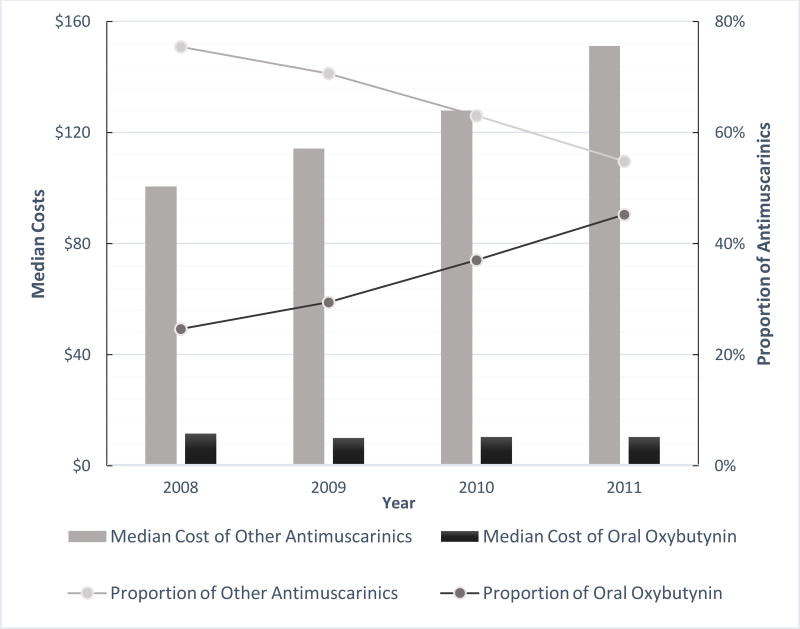

In 2008, the median total prescription cost for oral oxybutynin was $11.58, which decreased by 10.5% to $10.36 by 2011 (Figure 2). In 2008, the median total prescription cost for another antimuscarinics was $100.59, which increased by 50.3% to $151.24 by 2011.

Figure 2.

Differences in Total Costs Per year ($, Adjusted to 2011), Standardized to a 30 days’ Supply of Antimuscarinics

4 Discussion

This is the first study to examine the association of cognitive impairment among older adults who initiated on oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics. The relationship between cognitive impairment in the baseline period and prescribing of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics changed over time. Although slightly more patients with cognitive impairment were initiated on another antimuscarinic in each study year, use of the other antimuscarinics decreased progressively over time. If this trend continues, more patients with cognitive impairment treated with an antimuscarinic will initiate oral oxybutynin compared to other antimuscarinics. One likely explanation is drug costs. After standardizing costs to 2011 dollars, the total cost of oral oxybutynin decreased slightly over the study period, whereas the total cost of other antimuscarinics increased by 50% over the study period.

We compared use of oral oxybutynin vs other antimuscarinics based on several studies which suggested that oral oxybutynin may be associated with developing/worsening cognitive impairment11–13 compared to other antimuscarinics.11–16 Suehs and colleagues used a similar approach in evaluating cognitive impairment and the initiation of antimuscarinics in older adults enrolled in a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plan.36 However, this study did not distinguish between the initiation of oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics but instead used an approach that was informed by the 2012 American Geriatric Society (AGS) Beers Criteria, in which any medication with anticholinergic properties (including all antimuscarinics) was considered potentially inappropriate.37 Among the studies cited by the AGS Beers Criteria, oral oxybutynin was the only antimuscarinic considered;38–40 therefore, this recommendation regarding cognitive impairment may not be generalizable to other antimuscarinics.

Suehs found that 11.3% and 6.3% of patients treated with an antimuscarinic were previously diagnosed with dementia or treated with an antidementia medication, respectively, whereas in our study in which the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of dementia was 14.8% and the proportion treated with an antidementia medication was 11.2%. The higher prevalence of dementia and antidementia treatment in our study compared to that of Suehs may be due in part to our use of a fee-for-service Medicare population which, in general, is older relative to a Medication Advantage plan.41 The differences in the proportions with a prior diagnosis of dementia and anti-dementia treatment may also be due to the requirement of continuous enrollment for 12 months following the index date by Suehs, which would result in the exclusion of patients with cognitive impairment who died or changed coverage within one year following the index date. In addition, our overall prevalence of cognitive impairment may have been higher than Suehs as we incorporated diagnoses codes for memory loss in our definition of cognitive impairment.23

Our study identifies an opportunity for improved antimuscarinic prescribing in older adults with cognitive impairment as these patients should avoid agents potentially more likely to worsen cognitive impairment. Many approaches can be used to improve the quality of antimuscarinic prescribing in patients with cognitive impairment. Alerts in the electronic medical record or in community pharmacy drug-interaction packages may improve prescribing.42 A pharmacist can first assess the potential for a prescribing cascade, in which increased urinary symptoms due to an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor is potentially misidentified and was initiated on an antimuscarinic.28,29 However, this adverse event typically resolves by itself within days or weeks of initiation or dose-escalation. Among patients with a paid claim of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor during the baseline period, we found that approximately 15% of patients who had the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor initiated or dose-escalated in the three months prior to initiation of an antimuscarinic, regardless of whether it was oral oxybutynin or another antimuscarinic. However, it is likely that a smaller proportion of these patients’ symptoms are attributable to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor given the ≤ 7% incidence of this symptom.29–31 If an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor was initiated or dose-escalated in the previous three months based on prescription fill history, then the pharmacist should speak with the patient and consider contacting the provider to see if symptoms predate the initiation of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; if it does not, then the patient could be educated to not take the antimuscarinic to see if symptoms resolve on their own.

If the addition of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor does not appear to be related to a prescribing cascade, a community pharmacist can be alerted to the prescribing of oral oxybutynin in a patient treated with an antidementia medication. In this case, a pharmacist can contact the provider to recommend another antimuscarinic or beta-3 agonist that is less likely to worsen cognitive impairment. Among patients classified as having cognitive impairment who were initiated on oral oxybutynin in our study, 43% could have be identified in a community pharmacy setting based on a claim for an antidementia medication in the previous year. This suggests that an impact can be made by a pharmacist-directed intervention. However, the trend for increased use of oral oxybutynin may also be driven by formulary restrictions and co-payment costs. The initial prescribed antimuscarinic may not be the same as the one dispensed as switching to a less expensive or formulary-preferred medication may have occurred following provider approval. As many other antimuscarinics or mirabegron may not be available to patients due to formulary restrictions and increased co-payment costs,20 patients may have to choose between oral oxybutynin, which carries the risk of worsening cognition, or no treatment, which may result in sequelae such as falls, depression, or reduced quality of life due to untreated OAB.43–49 Moreover, mirabegron, a beta-3 agonist which improves OAB symptoms without blocking antimuscarinic receptors, may theoretically be a better option than other antimuscarinics; however, medication formularies and costs may make mirabegron difficult to afford for many patients after other antimuscarinics become generic. Research on oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics in patients with cognitive impairment is needed to assess if the costs of other antimuscarinics are offset by downstream costs (e.g., due differential impacts on cognition), which would provide support to use other antimuscarinics or mirabegron over oral oxybutynin in these patients.

There are also limitations to this study. Since this analysis used claims data, we were unable to capture clinical information such as severity of dementia; however, we controlled for variables which may have acted as proxies for aging and cognitive impairment. Second, fesoterodine (2008) and oxybutynin gel (2009), were not approved until after the beginning of the study period. But since fesoterodine comprised only 2.9% and oxybutynin gel 1.2% of new antimuscarinic users in 2011, the impact of the approval during the study period on our results is likely minimal. Third, although we explored different types of specialty providers that may influence differential prescribing, we were unable to confirm if a specialty provider was the specific prescriber for an antimuscarinic prescription. Fourth, we did not include more recently approved medications used to treat OAB such as mirabegron and onabotulinumtoxinA (a third line treatment option), as these medications were not approved or unavailable to treat OAB during the study period. However, we would anticipate the differential prescribing of these medications to be similar to other antimuscarinics, as mirabegron and onabotulinumtoxinA are not associated with cognitive impairment.50,51 Fifth, there is a potential for misclassification due to delayed coding for cognitive impairment following antimuscarinic initiation; however, there is no way to differentiate a delayed coding of cognitive impairment with the development of cognitive impairment potentially due to the antimuscarinic. Sixth, although we included the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, and memory loss, along with dementia as part of the definition for cognitive impairment, there is the potential for undercoding mild or early symptoms of cognitive impairment in which treatment with other antimuscarinics would be preferred, thus underestimating the number of persons with baseline cognitive impairment. There is also likely undercoding of dementia diagnosis as 28% of patients received an antidementia medication during the baseline period with no dementia diagnosis in the previous year. Seventh, there are no diagnosis codes for non-pharmacological options, the first-line treatment for overactive bladder; therefore, we were unable to determine if patients had a trial of this option prior to initiating on an antimuscarinic.

Despite these limitations there are strengths in this study. Using the 5% sample of Medicare prescription drug claims, this study is generalizable to the U.S. fee-for-service older adult population.

5. Conclusions

Using medication claims and diagnosis codes, we identified small differential prescribing between oral oxybutynin and other antimuscarinics in older adults with cognitive impairment. The majority of patients with baseline cognitive impairment who were prescribed an antimuscarinic appropriately received another antimuscarinic. However, we found an increasing trend of initial therapy using oral oxybutynin correlated with antimuscarinic costs from 2008 to 2011. This finding suggests quality improvement opportunities exist with regards to antimuscarinic prescribing in the older adult population with overactive bladder. Interventions to initiate patients with cognitive impairment on other antimuscarinics or mirabegron instead of oral oxybutynin may require policy changes due to differential costs and current formulary restrictions. Our study documents the need for quality improvement with regards to antimuscarinic prescribing in older adults as an increasing proportion oral oxybutynin in patients with cognitive impairment could contribute to worsening cognitive impairment.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1: List of ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes and Medications used in Analysis

Appendix 2: Oral Oxybutynin versus Other Antimuscarinic Prescribing by Cognitive Impairment, 2008–2011.

Key Points.

Patients with cognitive impairment are slightly more likely to be treated with another antimuscarinic versus oral oxybutynin.

During the study period, there was an increasing trend to use oral oxybutynin versus other antimuscarinics, potentially attributable to prescription costs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matthew Keller for his assistance with data abstraction of Medicare claims and assistance with programming.

Funding Statement:

Funded by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448, sub-award KL2TR000450, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in part by Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NIH) and by Grant Number R24 HS19455 (PI: V. Fraser) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and Grant Number KM1CA156708 through the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

SMV, MS, SAS, SJB, MAO have no conflicts of interest to report.

This research was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual International Meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, May 2017.

References

- 1.Milsom I, Stewart W, Thuroff J. The prevalence of overactive bladder. Am Journal Manag Care. 2000;6(11 Suppl):S565–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tubaro A. Defining overactive bladder: Epidemiology and burden of disease. Urology. 2004;64(6 Suppl 1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomelsky A. Urinary incontinence in the elderly female. Ann Longterm Care. 2009;17(10):41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheife R, Takeda M. Central nervous system safety of anticholinergic drugs for the treatment of overactive bladder in the elderly. Clin Ther. 2005;27(2):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagg A, Verdejo C, Molander U. Review of cognitive impairment with antimuscarinic agents in elderly patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1279–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline. Linthicum (MD): American Urological Association Education and Research Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay GG, Abou-Donia MB, Messer WS, Jr, Murphy DG, Tsao JW, Ouslander JG. Antimuscarinic drugs for overactive bladder and their potential effects on cognitive function in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2195–2201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chancellor M, Boone T. Anticholinergics for overactive bladder therapy: Central nervous system effects. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(2):167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staskin DR, Zoltan E. Anticholinergics and central nervous system effects: Are we confused? Rev Urol. 2007;9(4):191–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay GG, Wesnes KA. Pharmacodynamic effects of darifenacin, a muscarinic m selective receptor antagonist for the treatment of overactive bladder, in healthy volunteers. BJU Int. 2005;96(7):1055–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay GG, Staskin DR, MacDiarmid S, McIlwain M, Dahl NV. Cognitive effects of oxybutynin chloride topical gel in older healthy subjects: A 1-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32(10):707–714. doi: 10.1007/BF03261924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagg A, Dale M, Tretter R, Stow B, Compion G. Randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study investigating the effect of solifenacin and oxybutynin in elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: the SENIOR study. Eur Urol. 2013;64(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay G, Crook T, Rekeda L, et al. Differential effects of the antimuscarinic agents darifenacin and oxybutynin er on memory in older subjects. Eur Urol. 2006;50(2):317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Wesnes K. Assessment of cognitive function of the elderly population: Effects of darifenacin. J Urol. 2005;173(2):493–498. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000148963.21096.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staskin D, Kay G, Tannenbaum C, et al. Trospium chloride has no effect on memory testing and is assay undetectable in the central nervous system of older patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1294–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kay GG, Maruff P, Scholfield D, et al. Evaluation of cognitive function in healthy older subjects treated with fesoterodine. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(3):7–15. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.05.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaron LE, Morris TJ, Jahshan P, Reiz JL. An evaluation of patient and physician satisfaction with controlled-release oxybutynin 15 mg as a one-step daily dose in elderly and non-elderly patients with overactive bladder: Results of the STOP study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(8):1369–1379. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.709837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lackner TE, Wyman JF, McCarthy TC, Monigold M, Davey C. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the cognitive effect, safety, and tolerability of oral extended-release oxybutynin in cognitively impaired nursing home residents with urge urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):862–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay GG, Granville LJ. Antimuscarinic agents: Implications and concerns in the management of overactive bladder in the elderly. Clin Ther. 2005;27(1):127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.006. quiz 139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbass IM, Caplan EO, Ng DB, et al. Impact of overactive bladder step therapy policies on medication utilization and expenditures among treated medicare members. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(1):27–37. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: New-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St Germaine-Smith C, Metcalfe A, Pringsheim T, et al. Recommendations for optimal icd codes to study neurologic conditions: A systematic review. Neurology. 2012;79(10):1049–1055. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182684707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strom BL, Schinnar R, Karlawish J, Hennessy S, Teal V, Bilker WB. Statin therapy and risk of acute memory impairment. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1399–1405. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lund BC, Steinman MA, Chrischilles EA, Kaboli PJ. Beers criteria as a proxy for inappropriate prescribing of other medications among older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(11):1363–1370. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(1):59–66. doi: 10.1002/pds.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suissa S, Dell'aniello S, Vahey S, Renoux C. Time-window bias in case-control studies: Statins and lung cancer. Epidemiology. 2011;22(2):228–231. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182093a0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: The prescribing cascade. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1096–1099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):808–813. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto M, Imamura T, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, Mori E. Urinary incontinence: An unrecognised adverse effect with donepezil. Lancet. 2000;356(9229):568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starr JM. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment and urinary incontinence in alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):800–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grutzendler J, Morris JC. Cholinesterase inhibitors for alzheimer's disease. Drugs. 2001;61(1):41–52. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bang H, Zhao H. Cost-effectiveness analysis: A proposal of new reporting standards in statistical analysis. J Biopharm Stat. 2014;24(2):443–460. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2013.860157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang J. Using SAS® procedures freq, genmod, logistic, and phreg to estimate adjusted relative risks – a case study. 2011 Accessed at https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings11/345-2011.pdf.

- 36.Suehs BT, Davis C, Franks B, et al. Effect of potentially inappropriate use of antimuscarinic medications on healthcare use and cost in individuals with overactive bladder. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):779–787. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore AR, O'Keeffe ST. Drug-induced cognitive impairment in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1999;15(1):15–28. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):508–513. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, Barratt JD, Roughead EE. Multiple anticholinergic medication use and risk of hospital admission for confusion or dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1916–1922. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raetzman SO, Hines AL, Barrett ML, Karaca Z. Hospital stays in medicare advantage plans versus the traditional medicare fee-for-service program, 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015 Accessed at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb198-Hospital-Stays-Medicare-Advantage-Versus-Traditional-Medicare.jsp. [PubMed]

- 42.Reynolds JL, Rupp MT. Improving clinical decision support in pharmacy: Toward the perfect dur alert. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(1):38–43. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyman JF, Harkins SW, Choi SC, Taylor JR, Fantl JA. Psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70(3 Pt 1):378–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liberman JN, Hunt TL, Stewart WF, et al. Health-related quality of life among adults with symptoms of overactive bladder: results from a U.S. Community-based survey. Urology. 2001;57(6):1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00986-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coyne KS, Payne C, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. The impact of urinary urgency and frequency on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: results from a national community survey. Value Health. 2004;7(4):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sand PK, Goldberg RP, Dmochowski RR, McIlwain M, Dahl NV. The impact of the overactive bladder syndrome on sexual function: a preliminary report from the Multicenter Assessment of Transdermal Therapy in Overactive Bladder with Oxybutynin trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):1730–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hullfish KL, Fenner DE, Sorser SA, Visger J, Clayton A, Steers WD. Postpartum depression, urge urinary incontinence, and overactive bladder syndrome: Is there an association? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(10):1121–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melville JL, Delaney K, Newton K, Katon W. Incontinence severity and major depression in incontinent women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):585–592. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000173985.39533.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Thompson C, Bavendam T, Chen CI, Markland A. Prevalence and effect on health-related quality of life of overactive bladder in older Americans: Results from the epidemiology of lower urinary tract symptoms study. J Am Geritr Soc. 2011;59(8):1465–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagg A, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron for the treatment of symptoms of overactive bladder in older patients. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):666–675. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui Y, Zhou X, Zong H, Yan H, Zhang Y. The efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA in treating idiopathic OAB: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(5):413–419. doi: 10.1002/nau.22598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: List of ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes and Medications used in Analysis

Appendix 2: Oral Oxybutynin versus Other Antimuscarinic Prescribing by Cognitive Impairment, 2008–2011.