Abstract

Purpose

Is there a difference in implantation and pregnancy rates between embryos transferred electively at cleavage or blastocyst stage in infertile women ≤ 38 years with at least four zygotes on day 1 post retrieval?

Methods

A randomized clinical trial was conducted in a single tertiary care hospital with a sample size of 194 patients in each arm for a total population of 388 women. Patients less than 39 years of age with more than three fertilized oocytes and less than four previous assisted reproductive technology (ART) attempts were inclusion criteria.

Results

The two groups were similar for age, years of infertility, indication to treatment, basal antimüllerian hormone and FSH, number of previous ART cycles, primary or secondary infertility, type of induction protocol, days of stimulation, total gonadotrophin dose, and estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P) levels at trigger. No statistically significant differences were found in terms of number of retrieved oocytes, inseminated oocytes, fertilization rate, canceled transfers (7.73% in blastocyst and 3.61% in cleavage stage group), and cycles with frozen embryos and/or oocytes. Although a higher number of fertilized oocytes were in the blastocyst stage group (6.18 ± 1.46 vs 5.89 ± 1.54, p = 0.052), a statistically greater number of embryos/randomized cycle were transferred at cleavage stage (1.93 ± 0.371) compared with the number of transferred blastocysts (1.80 ± 0.56), probably due to the number of embryos not reaching blastocyst stage (3.09%). The implantation rate (28.37 vs 25.67%), pregnancy rate per cycle (36.06 vs38.66%), transfer (39.66 vs 40.11%), spontaneous abortions (19.72% vs 12.00%), delivery rate per cycle (27.84 vs 32.99%), and transfer (30.17 vs 34.22%) were not significantly different between the blastocyst and cleavage stage groups. The twin delivery rate was higher in the blastocyst stage group, although not significant (42.59 vs 28.12%). The mean numbers of frozen blastocyst (2.30 ± 1.40 vs 2.02 ± 1.00) and frozen oocytes (7.09 ± 3.55vs 6.79 ± 3.26) were not significantly different between the two groups.

Conclusions

Fresh blastocyst-stage transfer versus cleavage-stage transfer did not show any significant difference in terms of implantation and pregnancy rate in this selected group of patients. A high twin delivery rate in both groups (35.59%) was registered, and although not significant, they were higher in the blastocyst transfer group (42.59 vs 28.12%). Our conclusion supports considering single embryo transfer (SET) policy, even in cleavage stage in patients younger than 39 years with at least four zygotes.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT02639000

Keywords: IVF/ICSI, Cost-effectiveness, Prediction models, Blastocyst stage, Cleavage stage

Introduction

Background

Embryos from in vitro fertilization are routinely transferred into the woman’s uterus at cleavage stage (days 2 to 3) or at blastocyst stage (days 5 to 6). Over the last 15 years, a constant increase in the proportion of embryo transfers (ETs) at blastocyst stage has been reported [1]. The rationale behind this trend is the demonstrated advantages of blastocyst-stage transfer over the cleavage one in terms of implantation, healthy singleton live births, and reduction in the number of multiple pregnancies, while keeping the same pregnancy rates per transfer of cleavage-stage transfers. Blastocyst-stage transfer is more physiological since it provides better embryo-endometrium synchronization and consequently higher chances of implantation [2]. Secondly, it ensures the identification of embryos that have successfully initiated their embryonic genome DNA activation to occur at the eight-cell stage. Whereas, in the absence of the activation, the embryo will unlikely survive [3]. Thirdly, since embryo biopsy for chromosome screening is safer when performed after days 5–6, rather than at cleavage stage, growing embryos to the blastocyst stage is the most suitable for patients in need of genetic analyses [4]. Since 50–85% of human embryos carry chromosomal abnormalities, the blastocyst transfer after the biopsy could allow for the removal of genetically abnormal embryos prior to their transfer [5]. Although, severe critical points have been raised to the efficiency, efficacy, and clinical utility and safety of preimplantation chromosomal assessment [6, 7]. Lastly, blastocyst-stage transfer showed a significant increase in live birth rate [8] per started treatment (odds ratio [OR] 1.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.20–1.82). The reason why the blastocyst-stage transfer has not fully replaced the transfer of cleavage-stage embryos is because the delayed transfer still shows some disadvantages. One disadvantage, blastocyst transfer does improve the odds of transferring a viable embryo [9], however it does not guarantee euploidy since chromosomally abnormal embryos are still able to become blastocysts [4]. Second, by committing to embryo transfer at blastocyst stage, there is a risk of losing some embryos because of the difference between the in vitro culture and uterine environment. These embryos might not survive the challenges of extended culture, but might have survived in vivo if transferred on day 3. The consequence of this disadvantage is a lower cumulative pregnancy rate (i.e., number of births from one egg collection) in blastocyst-stage transfers compared with cleavage-stage ones [2, 10]. Third point is blastocyst-stage embryo transfer [11, 12] has been demonstrated to be associated with an adjusted higher relative risk (95% CI) of preterm (< 37 weeks) birth (AOR 1.32 [1.19 to 1.46]), but there was no difference in the adjusted odds for very preterm births (VPTBs), low birth weight (LBW), and very low birth weight (VLBW) and an increased rate of large-for-gestational-age newborns was found compared with those resulting from cleavage-stage embryos [13]. In 2013, a systematic review and meta-analysis of obstetric and perinatal complications in singleton pregnancies after the transfer of blastocyst-stage and cleavage-stage embryos reported that embryo transfer (ET) at the blastocyst stage was associated with a higher relative risk (RR; 95% confidence interval [CI]) of preterm (RR 1.27; 95% CI 1.22–1.31) and preterm delivery (RR 1.22; 95% CI 1.10–1.35) in comparison with those resulting from the transfer of cleavage-stage embryos and the risk of growth restriction was lower in babies conceived through blastocyst transfer (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.77–0.88). However, the authors of the study were not able to adjust for the confounders [12] and a recent paper reported that the risks of preterm and highly preterm births increased after fresh blastocyst transfers versus the risks after fresh cleavage-stage embryo transfers [14]. Although, with frozen embryo transfers, there were no differences. Blastocyst embryo transfers resulted in high risks of infants who were large for their particular gestational age, and cleavage-stage embryo transfers resulted in high risks of infants who were small for their gestational age [14].

Finally, the odds of congenital anomalies have been reported to be significantly higher for babies born after embryo transfer at blastocyst stage (1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.62), except for a small number of cases [11, 15]. Therefore, taking into consideration the pros and cons of these two transfer modalities, new studies are needed to clarify whether a real superiority of blastocyst-stage embryo transfer does exist over the cleavage stage one. Our Center, after most of the assisted reproductive technology (ART) restrictions have been removed in our country [16–18], decided to freeze, in most of the cases, only embryos at blastocyst stage to reduce the number of frozen and unused embryos. In addition, we have implemented a policy of single warmed blastocyst transfer (SET) together with a progressive reduction of the number of fresh embryos transferred. Here, we report a prospective randomized study analyzing cleavage-stage vs blastocyst-stage double embryo transfer (DET) in a selected group of patients. Since May 2009, most of the non-transferred embryos at cleavage stage are cultured until days 5–6 and frozen by vitrification. In order to reduce the number of supernumerary frozen embryos in good prognosis patients, not all the mature oocytes are inseminated/injected and are frozen by vitrification [19, 20].

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Patients with a diagnosis of primary or secondary infertility with a clinical indication for IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and under 39 years of age were enrolled in the study and randomized to cleavage- (CS) or blastocyst-stage (BS) transfer if they had more than three fertilized oocytes (zygotes) the day after insemination/injection. Couples with three or more failed previous IVF/ICSI cycles were excluded based on our previous quality performance analysis as a reduced prognosis population [18]. Couples involved in other clinical or embryological trials or at high risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) were also excluded.

This trial was designed to review our results and internal policy to implement the number of SET, after a long period in which even in very young patients three embryos had to be transferred if available, due to legal restrictions to embryo freezing [16].

Interventions

All enrolled patients underwent a stimulation treatment for IVF/ICSI, and oocyte retrieval was performed with transvaginal ultrasound (TV-US) guidance under deep sedation. On day 1 after retrieval, patients were randomly assigned to one of the two study groups by the embryologist in charge, if they matched the inclusion criteria of at least four fertilized oocytes. For patients in the cleavage-stage group, two embryos at cleavage stage were transferred, while for the ones in the blastocyst-stage group, two blastocysts were transferred, when available. In both cases, the embryo transfer was performed under TA-US guidance using a soft catheter by professionals with a minimum of 6 months of training.

Objectives

Primary end point

A comparison was made between the probabilities of embryo implantation and pregnancy after ET of two embryos at blastocyst stage (day 5–6) and the same probabilities after ET two embryos at cleavage stage (day 2 or 3) in women ≤ 38 years of age after cycles of IVF or ICSI and ET because of couple infertility.

Secondary end points

Whether a higher rate of twin pregnancies does exist among patients with ET at blastocyst stage was observed, which may justify, in the near future, a shift towards a single-blastocyst transfer instead of a two-blastocyst ET even in fresh embryo transfers. An investigation was made if blastocyst transfer reduces the number of frozen blastocysts.

Pregnancy outcomes, delivery and abortion rates, and fetal or perinatal anomalies were also evaluated.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes evaluated were implantation and pregnancy rates in the two groups. The secondary outcomes investigated possible differences in multiple pregnancy rate, delivery rate, and pregnancy outcome between blastocyst-stage and cleavage-stage groups. Pregnancies were followed until the end of the perinatal period (28 days after delivery).

Sample size

Based on our preliminary experience and available data when the study was designed [21, 22], an expected pregnancy probability of 32% for cleavage-stage ETs and of 47% for blastocyst ones was calculated; considering a one-tailed alpha error of 5% and a power of 90%, a total of 194 patients in each arm for a total population of 388 women were needed. An ad interim analysis was performed when one third of the total study population had been recruited. These two treatments were considered significantly different only with a p < 0.0007.

Randomization

Patients were enrolled by the gynecologists during the first encounter before the start of the follicular stimulation cycle. A block randomization was performed, and the randomization sequences were generated by the biostatistician on an Excel file. The allocation concealment was not performed. Patients were assigned to the study groups by the embryologist on day 1 after fertilization. Blind assignation was not possible, even if the embryologist was blinded of the block allocation until the time of randomization. Open block randomization was performed with the embryologist in charge following the order of randomization, blind to the clinical staff.

Statistical methods

All the data are expressed in numbers and percentages or means and standard deviations whenever appropriate. The analysis has been carried out for all the randomized patients; data have been analyzed with Stata 13.0 (2013, StataCorp, Texas, USA). The pregnancy probability between the two groups is compared with a χ 2, test and the secondary end points in the two groups are compared using a χ 2 test or Wilcoxon test, where appropriate. Due to the long period of enrollment, all analyzed p values were time corrected. The results of the ad interim analysis are considered significant with p < 0.0007, those of the final analysis with p < 0.049. Our center maintains an external audit anonymized electronic research query system, exported from our certified-only access web database, which at the time of this analysis included 25,911 consecutive fresh non-donor IVF cycles and 4792 frozen embryo cycles. Patients who underwent these cycles had consented in writing that their medical records could be used for research purposes, as long as the patients’ anonymity was protected and confidentiality of the medical record was assured. The study protocol and specific consent form have been approved by our Ethical Committee on June 24, 2010.

Results

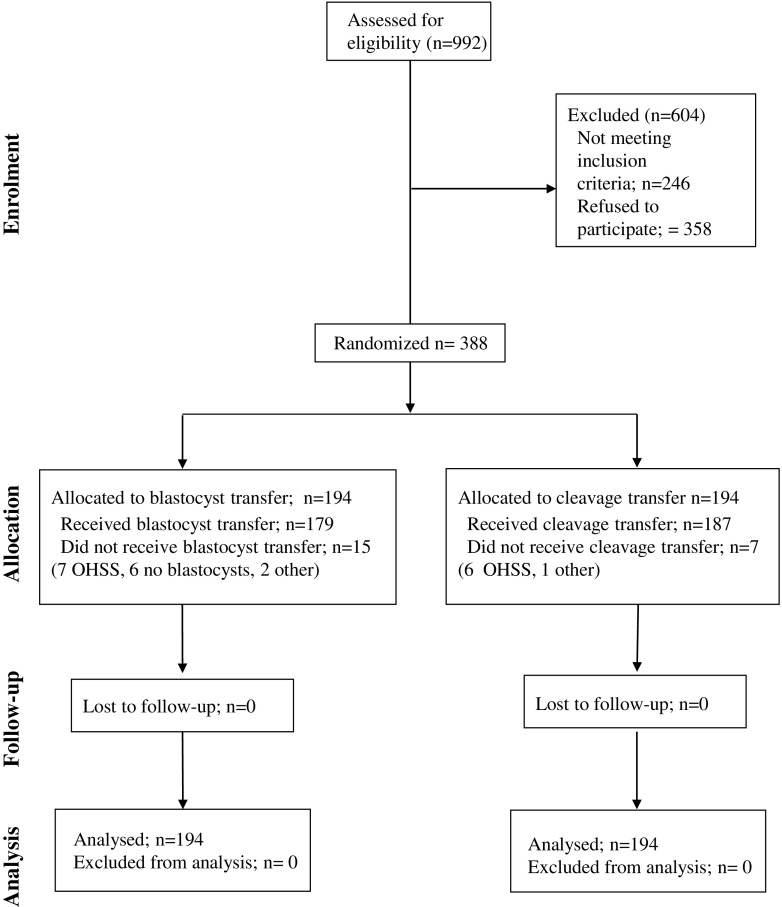

The patients’ flow through all the study stages, from enrollment to follow-up, is shown in Fig. 1. Nine hundred ninety-two couples were assessed for eligibility, 604 were excluded, 246 (24.80%) not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded, and 358 (36.09%) refused to participate. Three hundred eighty-eight were randomized (194 in each group). In the blastocyst group, 179 underwent the transfer and 15 did not (7 for OHSS risk, 6 for failed fertilization or cleavage, 2 for other reasons). In the cleavage stage group, 187 received transfer and 7 did not (6 for OHSS risk, 1 for other reasons). Three hundred eighty-eight cases were fully analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram

The enrollment and follow-up period lasted from July 15, 2010, to March 3, 2016. Among the included patients, no one was lost at follow-up nor excluded from the analysis. The baseline data recorded for each patient at the moment of enrollment are reported in Table 1. According to the inclusion criteria, the study population consisted of quite good prognosis patients: young age (mean 33.4 ± 2.9 years), low basal FSH (mean 6.80 ± 2.16 ng/mL), high antimüllerian hormone (AMH), and antral follicular count (AFC), 3.38 ± 3.02 ng/mL and 11.75 ± 7.21, respectively. Two hundred eighty-one (72.42%) females were younger than 35 years, 237 (61.08%) were at their first ART attempt, and none had previous deliveries after ART. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of age, years of infertility, basal AMH and FSH, AFC, number of previous ART cycles, and primary or secondary infertility. Only the BMI variable shows a mild discrepancy between the blastocyst group and the cleavage-stage one: a BMI of 21.7 for the first and of 22.2 for the second group with a p value of 0.030. The etiologies of infertility and the indications to ART were similar between groups. The only variable showing a higher prevalence, although not significant, between blastocyst-group women than among cleavage-group ones is endometriosis (6.7% for the blastocyst group and 1.6% for the cleavage-stage one), although they represent only 4.12% of the studied population. Table 2 reports all the main ART cycle characteristics, and in this case, the groups were homogeneous in terms of induction protocol and length, total dose of gonadotropins, estrogen and progesterone levels on trigger day, semen quality, total number of retrieved oocytes per patient and of inseminated ova, fertilization rate, percentages of immediate transfers and of cycles with frozen embryos or oocytes (according to our internal protocols, we never inseminate more than 8–10 mature oocytes in this population), and absolute number of frozen embryos and oocytes. The antagonist protocol was the one of choice in more than 60% of cases. No cycles were suspended due to a premature rise of progesterone level in this series. No differences were found in culture media: blastocyst stage—192 sequential e 2 single step, cleavage stage 193 sequential e 1 single step (p = 1.000). Both groups had a good response in terms of number of retrieved and mature oocytes. Male factor was the main indication to treatment in 192 (49.49%) couples, and in 27 cycles (6.96%), testicular frozen sperm was used. No differences were found in the mean total sperm count, progressive motility, normal forms, and number of cycles with frozen testicular sperm (Table 2). The semen quality observed the day of oocyte retrieval was on average good; however, for the vast majority of patients, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) procedure was preferred.

Table 1.

Basal characteristic of patients enrolled in the study on cleavage vs blastocyst, mean ± SD/number (%)

| Variable | All | Blastocyst | Cleavage | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 388 | 194 | 194 | |

| Female age | 33.4 ± 2.9 | 33.5 ± 2.9 | 33.4 ± 2.9 | 0.684 |

| Female age ≤ 35 years (%) | 281 (72.42%) | 142 (73.20%) | 139 (71.65%) | 0.820 |

| Years of infertility | 4.19 ± 6.06 | 3.96 ± 2.17 | 4.42 ± 8.29 | 0.501 |

| BMI | 21.96 ± 3.16 | 21.69 ± 3.16 | 22.23 ± 3.14 | 0.090 |

| Smoking | 78 (20.10%) | 41 (21.13%) | 37 (19.07%) | 0.609 |

| Secondary infertility | 92 (23.71%) | 42 (21.65%) | 50 (25.77%) | 0.403 |

| Previous deliveries | 10 (2.58%) | 3 (1.55%) | 7 (3.61%) | 0.337 |

| Previous deliveries after ART | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Previous abortions | 60 (15.54%) | 27 (14.06%) | 33 (17.01%) | 0.483 |

| Basal FSH (ng/mL) | 6.80 ± 2.16 | 6.75 ± 1.86 | 6.86 ± 2.43 | 0.628 |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 3.38 ± 3.02 | 3.24 ± 2.26 | 3.50 ± 3.58 | 0.535 |

| Antral follicular count | 11.75 ± 7.21 | 11.72 ± 7.25 | 11.77 ± 7.20 | 0.875 |

| Previous ART cycles | 2.05 ± 1.00 | 2.05 ± 0.98 | 2.06 ± 1.01 | 0.599 |

| First ART cycle (%) | 237 (61.08%) | 115 (59.28%) | 122 (62.89%) | 0.532 |

| Indication to treatment | 0.870 | |||

| Male | 192 (49.48%) | 95 (48.97%) | 97 (50.00%) | 0.805 |

| Tubal | 62 (15.98%) | 30 (15.46%) | 32 (16.49%) | 0.779 |

| Unexplained | 45 (11.60%) | 25 (12.89%) | 20 (10.31%) | 0.419 |

| Male and female factor | 43 (11.08%) | 20 (10.31%) | 23 (11.86%) | 0.640 |

| Endometriosis | 16 (4.12%) | 13 (6.70%) | 3 (1.55%) | 0.019 |

| Ovulatory | 15 (3.87%) | 4 (2.06%) | 11 (5.67%) | 0.215 |

| Reduced ovarian reserve | 10 (2.58%) | 3 (1.55%) | 7 (3.61%) | 0.076 |

| Multiple female factors | 5 (1.29%) | 4 (2.06%) | 1 (0.52%) | 0.205 |

Table 2.

ART cycle characteristics, total, and by groups (mean ± SD/number (%))

| Variable | All | Blastocyst | Cleavage | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction protocol | 0.478 | |||

| Antagonist cycle | 236 (60.82) | 122 (61.89) | 114 (58.76) | |

| Agonist flare | 21 (5.41) | 8 (4.12) | 13 (6.70) | |

| Agonist long | 131 (33.76) | 64 (32.99) | 67 (34.54) | |

| Induction days | 11.5 ± 1.5 | 11.4 ± 1.6 | 11.7 ± 1.4 | 0.142 |

| Total gonadotrophin dose | 2188 ± 1805 | 2086 ± 1144 | 2291 ± 2281 | 0.340 |

| E2 at HCG | 1848 ± 929 | 1821 ± 951 | 1878 ± 908 | 0.559 |

| Progesterone at HCG | 1.04 ± 0.70 | 1.01 ± 0.56 | 1.07 ± 0.82 | 0.446 |

| Procedure performed | 0.244 | |||

| IVF | 32 (8.25%) | 19 (9.79%) | 13 (6.70%) | |

| ICSI | 329 (84.79%) | 163 (84.02%) | 166 (85.57%) | |

| ICSI/TESE | 27 (6.96%) | 12 (6.19%) | 15 (7.73%) | |

| Total sperm count (× 106) | 74.85 ± 73.00 | 77.41 ± 77.95 | 72.13 ± 67.50 | 0.432 |

| Progressive motility (%) | 20.95 ± 10.59 | 20.47 ± 11.03 | 21.44 ± 10.12 | 0.437 |

| Normal forms (%) | 3.75 ± 1.74 | 3.74 ± 1.92 | 3.75 ± 1.52 | 0.911 |

| Oocytes retrieved | 12.61 ± 5.02 | 12.99 ± 5.28 | 12.23 ± 4.73 | 0.137 |

| Mature oocytes | 9.55 ± 4.37 | 9.82 ± 4.56 | 9.29 ± 4.17 | 0.236 |

| Inseminated oocytes | 7.59 ± 1.74 | 7.74 ± 1.77 | 7.44 ± 1.71 | 0.090 |

| Fertilized oocytes | 6.03 ± 1.51 | 6.18 ± 1.46 | 5.89 ± 1.54 | 0.052 |

| Fertilization rate (%) | 80.71 ± 14.85 | 81.17 ± 14.46 | 80.24 ± 15.26 | 0.532 |

| Transfers (%) | 366 (94.33) | 179 (92.27) | 187 (96.39) | 0.086 |

| Cycles with no transfer | 22 (5.67) | 15 (7.73) | 7 (3.61) | 0.123 |

| OHSS | 13 | 7 | 6 | |

| No cleavagea | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Other complicationsb | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Embryos transferred/randomized cycle | 1.86 ± 0.48 | 1.80 ± 0.56 | 1.93 ± 0.37 | 0.002 |

| Embryos transferred/transfer | 1.98 ± 0.16 | 1.95 ± 0.22 | 2 | 0.002 |

| At least 1 top-quality embryo (type 1 in G2) | 184 (47.42%) | 89 (45.88%) | 95 (48.97%) | 0.611 |

| Cycles with frozen embryos | 239 (61.60%) | 110 (56.70%) | 129 (66.49%) | 0.048 |

| Cycles with frozen oocytes | 88 (22.68%) | 45 (23.20%) | 43 (22.16%) | 0.816 |

| Frozen embryos | 2.15 ± 1.21 | 2.30 ± 1.40 | 2.02 ± 1.00 | 0.773 |

| Frozen oocytes | 6.94 ± 3.39 | 7.09 ± 3.55 | 6.79 ± 3.26 | 0.692 |

aNo embryo development at blastocyst stage or arrested at cleavage stage

bTwo maternal gastroenteritis + embryos vitrified due to cervical stenosis

The fertilization rate was similar in both groups (81.2% for the blastocyst group and 80.2% for the cleavage-stage one), with a slightly, not significant, higher number of fertilized oocytes in the blastocyst arm (6.18 and 5.89, respectively, with p = 0.052).

One hundred eighty-four (47.42%) cycles had at least one top-quality embryo as scored on day 2 by the Istanbul criteria [23], 45.88% in the blastocyst group, and 48.97% in the cleavage-stage group, not significantly different between the two studied groups.

A significantly greater (p = 0.002) mean number of embryos/randomized cycles was transferred at cleavage stage (1.93 ± 0.37) compared with the number of transferred blastocysts (1.80 ± 0.56), explained by the lower percentage of embryos developing in vitro up to the blastocyst stage as compared to embryos reaching the third day post fertilization. The cleavage-stage group had more supernumerary embryos to cryopreserve than those in the blastocyst arm (129/194 patients against 110/194 in the blastocyst group), with 2.02 ± 1 and 2.3 ± 1.4 of cryopreserved embryos, respectively, but this difference was not statistically significant (66.49 vs 56.70%). No statistical difference (Table 2) was found in the number of vitrified oocytes between the two groups (7.09 ± 3.55 vs 6.79 ± 3.26 (p = 0.692). Thirty-two patients in the cleavage stage and 32 in the blastocyst group were younger than 35 years, were at their first ART attempt, had at least one top-quality embryo (G2 grade 1), and comprised 16% of the patients, considered favorable outcome by the 2017 ASRM criteria [24].

Primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Table 3. The implantation rate (%) was 28.37 ± 39.00 in the blastocyst group and 25.67 ± 34.96, p = 0.741, in the cleavage-stage group (Table 3), and the pregnancy rate was 36.60 vs 38.66%, p = 0.753. No statistically significant differences were found in implantation and pregnancy rates, between the two groups.

Table 3.

Results

| Variable | All | Blastocyst | Cleavage | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implantation rate (%) | 26.99 ± 36.96 | 28.37 ± 39.00 | 25.67 ± 34.96 | 0.489 |

| Pregnancies per retrieval (%) | 146 (37.63%) | 71 (36.60%) | 75 (38.66%) | 0.673 |

| Pregnancies per transfer (%) | 146 (39.89%) | 71 (39.66%) | 75 (40.11%) | 0.927 |

| Intrauterine pregnancies with embryonic heart rate | 0.280 | |||

| Single pregnancies | 87 (64.93%) | 39 (60.00%) | 48 (69.57%) | |

| Twin pregnancies | 47 (35.07%) | 26 (40.00%) | 21 (30.43%) | |

| Ectopic pregnancies (%) | 3/146 (2.05%) | 2/71 (2.82%) | 1/75 (1.33%) | 0.612 |

| Spontaneous abortions (%) | 23/146 (15.75%) | 14/71 (19.72%) | 9/75 (12.00%) | 0.257 |

| Therapeutics abortions | 2/146 (1.37%) | 1/71 (1.41%) | 1/75 (1.33%) | 1.000 |

| Delivery rate per cycle | 118/388 (30.41%) | 54/194 (27.84%) | 64/194 (32.99%) | 0.272 |

| Delivery rate per transfer | 118/366 (32.24%) | 54/179 (30.17%) | 64/187 (34.22%) | 0.412 |

| Pregnancies reaching delivery (%) | 118/146 (80.82%) | 54 (76.06%) | 64 (85.33%) | 0.174 |

| Deliveries | ||||

| Single (%) | 77 (52.73) | 31 (57.40) | 46 (71.87) | 0.122 |

| Male/female ratio | 36/41 (0.88) | 15/16 (0.94) | 21/25 (0.84) | 0.821 |

| Gestational week | 39.2 ± 1.8 | 39.1 ± 2.2 | 39.2 ± 1.5 | 0.657 |

| Weight (g) | 3198 ± 572 | 3104 ± 680 | 3262 ± 481 | 0.453 |

| Twins (%) | 42 (35.59) | 23 (42.59) | 18 (28.12) | 0.122 |

| Male/female ratio | 42/40 (1.05) | 23/23 (1.00) | 18/17 (1.12) | 0.826 |

| Gestational week | 35.2 ± 3.0 | 34.5 ± 3.5 | 35.9 ± 2.0 | 0.072 |

| Weight (g) | 2226 ± 538 | 2124 ± 599 | 2350 ± 428 | 0.168 |

| Neonatal anomalies (%)a | 2/159 (1.26) | 2/77 (2.60) | 0/82 | 0.233 |

aOne diaphragmatic hernia in a twin pregnancy and one polydactyly

The prevalence of multiple pregnancies (twins) is high in both groups although not significantly different, with 26/71 (40.00%) for blastocyst-stage and 22/75 (31.88%) for cleavage-stage embryos. No fetal reductions were performed, and no monozygotic twins were observed as defined by early transvaginal ultrasound criteria [25]. No statistically significant differences were observed for ectopic pregnancies, spontaneous and therapeutic abortions for fetal anomalies, male/female ratios, gestational age, and birth weight at delivery and neonatal anomalies both in single than in twin pregnancies (Table 3).

Adverse events

Few particular adverse events have been reported: only two episodes of gastroenteritis during the stimulation cycle and one case of stenosis of the internal cervical OS complicating the embryo transfer. In terms of congenital malformations, one case of diaphragmatic hernia was reported in a twin pregnancy and one of polydactyly, both in the blastocyst-stage transfer group.

Discussion

Fresh blastocyst-stage transfer versus cleavage-stage transfer did not show any significant difference in terms of implantation and pregnancy rates in this selected group of patients.

As worldwide reported, embryo transfer at blastocyst stage is increasing consistently over the years, reaching almost one third of all the transfers performed nowadays [26]. At the same time, as summarized by the Cochrane [2] systematic review updated in 2016, the evidences in favor of blastocyst transfer are still of low-quality level.

This study is actually one of the largest to our knowledge with such homogenous inclusion criteria, even if different from what is generally stated in terms of good-prognosis patients [27, 28]. Our data, in contrast with the latest literature, show no statistically significant differences in terms of implantation rate and pregnancy rate. At the same time, there were no significant differences in the two groups in terms of cycles with no embryos for transfer and in terms of the number of frozen oocytes and frozen blastocysts.

Nowadays, reproducibility is one of the main topics of discussion in scientific papers worldwide [29]. Much less attention has been paid until now to the issues involved with reporting negative results, particularly when seeming to refute a previous positive report or reports [30], stressing possible bias that could explain the absence in our results of evidence between different stages of embryo transfer.

In our report, the prevalence of multiple pregnancies, instead, is higher, although non-significant, in the group of blastocyst-stage transfer: 26/71 pregnancies (40%) for blastocyst and 22/75 for cleavage stage (31.88%). This is in line with the report of the National ART Surveillance System (NASS) for the year 2012 in the USA [26]: the transfer of two fresh blastocysts represents one of the four groups at higher risk for multiple pregnancies. This investigation was approved by our Ethical Committee in June 2010 when the last ASRM guidelines recommended [27] to transfer in favorable couples (first cycle of IVF, good embryo quality, excess embryos available for cryopreservation, or previous successful IVF cycle) the following: < 35-year-olds, one to two cleavage-stage embryos, one blastocyst; 35–37-year-olds, two cleavage-stage embryos or two blastocysts; 38–40-year-olds, three cleavage-stage embryos or two blastocysts; and more embryos in other conditions. Long after starting randomization, the ASRM practice committee [27] recommended limits on the number of embryos to transfer as two for cleavage-stage embryos in favorable prognosis and three embryos in all others, and two blastocysts in favorable prognosis and three in all others for women aged 35–37. In women 38–40, the number of recommended cleavage-stage embryos was three or four and two or three at blastocyst stage. Therefore, even 3 years prior to the 2013 ASRM recommendations [27], our policy was to reduce the number of embryos transferred. In this RCT, our criteria were more restrictive than the ASRM 2013 (favorable 1 first cycle of IVF, good embryo quality, excess embryos available for cryopreservation, or previous successful IVF cycle). The April 2017 ASRM statement [24] was published after our trial had been concluded. Still, our criteria were more restrictive than those proposed by the ASRM for SET (beside young age, the following characteristics have been associated with a favorable prognosis: (1) anticipating one or more high-quality embryos available for cryopreservation; (2) euploid embryos; and (3) previous live birth after an IVF cycle).

Some differences, although not statistically significant, were found in gestational age and the birth weight that could be explained by the prevalence of twin pregnancies in the blastocyst transfer group.

An important limitation of this study is the length of the study itself: it took 6 years to be completed, meaning that some protocols and culture techniques may have changed over time, although multiple regression analysis did not find a time-related difference in the studied population. Recruitment was particularly difficult even if 15.049 IVF/ICSI cycles were performed in the period 2010–2016, but with a female partner mean age of 37.02 ± 4.00 and 48% of couples with more than three failed previous attempts in our or other centers. Moreover, 992 patients were assessed for eligibility, but 664 had to be excluded, 246 not meeting the inclusion criteria (4 zygotes), and 358 refusing to participate after detailed and repeated protocol explanation. A second point to be underlined is the one of the ad interim analysis: although this analysis had brought very similar results that were expected for the final analysis, the investigators decided nonetheless to complete the protocol. This decision was taken in the perspective that the continuation of the study would have caused no detrimental effects to the patients. Although our protocol includes single blastocyst vitrification and warming, double embryo transfer is still routinely performed in fresh transfers in this group of patients and single blastocyst transfer in blastocyst transfer is still an option few patients accept even if strongly counseled by the clinical staff.

Another limitation is that this study took into consideration only the first fresh transfer per patient: as recently stressed, the analysis of cumulative pregnancy rate per started cycle [31] gives a wider picture and the best evidences to support a therapeutic approach. It is possible, although not considered in our results, that both groups could have similar cumulative pregnancy rates, since there was no statistical significant difference in cycles with elective supernumerary oocyte or blastocyst vitrification.

In conclusion, in our experience no differences exist between cleavage- and blastocyst-stage fresh transfer strategy in women less than 39 years and with at least four zygotes on day 1 post fertilization. A very high twin delivery rate was observed in both groups with an impressive higher rate, although not significant in the blastocyst-stage group, supporting a stronger work for patients’ acceptance of a general SET policy even in a population with a wider than strictly stated for favorable prognosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge and sincerely thank all the Humanitas Fertility Center staff for their unique support in conducting this study. We thank Pasquale Patrizio, Yale Fertility Center, for his support in revising the manuscript.

Author’s roles

PELS, EA, and EM were involved in the study concept and design. FC, EA, and AS contributed to the acquisition of data. EM analyzed data. PELS, FC, and GEGM wrote the manuscript and had a primary responsibility for the final content. PELS supervised the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study protocol and specific consent form have been approved by our Ethical Committee on June 24, 2010.

ᅟ

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Fertility treatment 2014 – Trends and figures. In. www.hfea.gov.uk. 2009–2010.

- 2.Glujovsky D, Farquhar C, Quinteiro Retamar AM, Alvarez Sedo CR, Blake D. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(6):CD002118. 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gosden RG. Oogenesis as a foundation for embryogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;186:149–153. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Spath K, Wells D. Morphological and cytogenetic assessment of cleavage and blastocyst stage embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:117–126. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capalbo A, Rienzi L, Cimadomo D, Maggiulli R, Elliott T, Wright G, et al. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: an observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gleicher N, Orvieto R. Is the hypothesis of preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) still supportable? A review J Ovarian Res. 2017;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13048-017-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orvieto R. Re-analysis of aneuploidy blastocysts with an inner cell mass and different regional trophectoderm cells. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:827. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0914-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glujovsky D, Farquhar C. Cleavage-stage or blastocyst transfer: what are the benefits and harms? Fertil Steril. 2016;106:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harton GL, Munné S, Surrey M, Grifo J, Kaplan B, McCulloh DH, et al. Diminished effect of maternal age on implantation after preimplantation genetic diagnosis with array comparative genomic hybridization. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(7):CD002118. 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Dar S, Lazer T, Shah PS, Librach CL. Neonatal outcomes among singleton births after blastocyst versus cleavage stage embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:439–448. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maheshwari A, Kalampokas T, Davidson J, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from the transfer of blastocyst-stage versus cleavage-stage embryos generated through in vitro fertilization treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1615–21.e1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins WP, Nastri CO, Rienzi L, van der Poel SZ, Gracia CR, Racowsky C. Obstetrical and perinatal outcomes following blastocyst transfer compared to cleavage transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2561–2569. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Du M, Guan Y, Wang B, Zhang J, Liu Z. Comparative neonatal outcomes in singleton births from blastocyst transfers or cleavage-stage embryo transfers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15:36. doi: 10.1186/s12958-017-0255-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maheshwari A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S. Should we be promoting embryo transfer at blastocyst stage? Reprod BioMed Online. 2016;32:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levi Setti PE, Albani E, Matteo M, Morenghi E, Zannoni E, Baggiani AM, et al. Five years (2004-2009) of a restrictive law-regulating ART in Italy significantly reduced delivery rate: analysis of 10,706 cycles. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:343–349. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi Setti PE, Morenghi E, Sonia C, Galliera S, Arfuso V, Menduni F. Restrictive law regulating art in Italy significantly reduced delivery rate in infertile patients art cycles. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:S265–S2S6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.07.1023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi Setti PE, Albani E, Cesana A, Novara PV, Zannoni E, Baggiani AM, et al. Italian Constitutional Court modifications of a restrictive assisted reproduction technology law significantly improve pregnancy rate. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:376–381. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi-Setti PE, Borini A, Patrizio P, Bolli S, Vigiliano V, De Luca R, et al. ART results with frozen oocytes: data from the Italian ART registry (2005-2013) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0629-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levi-Setti PE, Patrizio P, Scaravelli G. Evolution of human oocyte cryopreservation: slow freezing versus vitrification. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:445–450. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Blastocyst culture and transfer in clinical-assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S174–S177. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Blastocyst culture and transfer in clinical-assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:S89–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Istambul Consensus workshop on embryo assessment:proceeding of an expert meeting. In. Vol. 26(6). Human Reprod, 2011;1270–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Guidance on the limits to the number of embryos to transfer: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:901–903. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neilson JP, Danskin F, Hastie SJ. Monozygotic twin pregnancy: diagnostic and Doppler ultrasound studies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:1413–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb06305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kissin DM, Kulkarni AD, Mneimneh A, Warner L, Boulet SL, Crawford S, et al. Embryo transfer practices and multiple births resulting from assisted reproductive technology: an opportunity for prevention. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Criteria for number of embryos to transfer: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and the Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1518–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meldrum DR, Su HI. There’s no difference-are you sure? Fertil Steril. 2017;108(2):231–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.De Vos A, Van Landuyt L, Santos-Ribeiro S, Camus M, Van de Velde H, Tournaye H, et al. Cumulative live birth rates after fresh and vitrified cleavage-stage versus blastocyst-stage embryo transfer in the first treatment cycle. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2442–2449. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]