Abstract

In underground hibernacula temperate northern hemisphere bats are exposed to Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungal agent of white-nose syndrome. While pathological and epidemiological data suggest that Palearctic bats tolerate this infection, we lack knowledge about bat health under pathogen pressure. Here we report blood profiles, along with body mass index (BMI), infection intensity and hibernation temperature, in greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis). We sampled three European hibernacula that differ in geomorphology and microclimatic conditions. Skin lesion counts differed between contralateral wings of a bat, suggesting variable exposure to the fungus. Analysis of blood parameters suggests a threshold of ca. 300 skin lesions on both wings, combined with poor hibernation conditions, may distinguish healthy bats from those with homeostatic disruption. Physiological effects manifested as mild metabolic acidosis, decreased glucose and peripheral blood eosinophilia which were strongly locality-dependent. Hibernating bats displaying blood homeostasis disruption had 2 °C lower body surface temperatures. A shallow BMI loss slope with increasing pathogen load suggested a high degree of infection tolerance. European greater mouse-eared bats generally survive P. destructans invasion, despite some health deterioration at higher infection intensities (dependant on hibernation conditions). Conservation measures should minimise additional stressors to conserve constrained body reserves of bats during hibernation.

Introduction

Life history theory suggests that organisms optimise their defences against pathogens by differential allocation of resources to support different physiological functions1–4. There is a trade-off mechanism applied to modulate investment into individual life history components5,6. Homeostasis and survival of hosts challenged with exposure to a pathogenic agent could be considered a physiological measure of health2. Host physiological status under pathogen pressure will be impacted by standard components of the ‘disease triangle’, i.e., host susceptibility, virulence of the infectious agent and environmental determinants. In general, hibernation, a slow life history strategy, is linked to higher survival rates7. Successful hibernation of mammals is constrained by their energy reserves, suitable microhabitat availability8 and thermoregulatory behaviour9. Additional stressors may deplete the animal’s resources, resulting in adverse consequences.

Skin, the largest organ of the body, acts as a barrier between the animal and its environment while providing multiple anatomic and physiological functions. A bat’s membranes are essential for flight, increasing the ratio of body mass to body surface. Moreover, naked flight membranes have a surface area eight times greater than that of fur-coated skin. This increases the area of potential exposure to dermatopathogens. In bats, healthy skin is essential for maintaining physiological homeostasis10.

In the northern temperate zone, hibernating bats are exposed to a non-systemic fungal infection that mainly affects the areas of skin without fur. Over the last decade, the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans has caused a devastating decline in North American bat populations11–16. During this time, there have been only sporadic cases of mortality in Eurasia17–21. In contrast to standard cutaneous dermatomycoses, the so-called white-nose syndrome (WNS) fungus invades living layers of skin10,22,23.

Despite considerable advances in our understanding of molecular pathogenesis and factors affecting the virulence of P. destructans infection24–27, the fundamental pathophysiological mechanisms of mortality associated with WNS remain unconfirmed10,28,29. Adverse effects increase with the extent of wing membrane pathology. While early stages of skin infection induce a two-fold increase in fat energy utilisation29, late-stage infected bats have altered torpor-arousal cycles, abnormal hibernation behaviour as well as emaciation and increased mortality30. Several studies of clinical blood parameters (e.g. electrolytes, acid-base balance, hydration status, haematology) in little brown bats, Myotis lucifugus, reveal that WNS disrupts blood homeostasis29,31,32. Interestingly, European P. destructans isolates are virulent and produce WNS in this North American bat species33. Infected bats have histopathology identical to skin lesions in Palearctic bat species18–22. P. destructans occurred in Europe before the outbreak of the Nearctic epidemic34,35. This, together with phylogenetic studies36,37, indicates that North American species of bats might be naïve hosts to a fungal pathogen originating in the Palearctic region. Intercontinental and interspecies comparisons may provide greater insights into variation of host responses to fungal infection.

Two defence mechanisms can evolve from host-pathogen interactions: resistance and tolerance38–40. Resistance protects the host by reducing the pathogen burden. As a consequence, prevalence of the agent in the host population decreases. In comparison, tolerant hosts limit the damage caused by the pathogen and remain healthy without mounting sterilising immunity41, though prevalence remains high or even increases within the susceptible population. Host cost/benefit trade-offs from its response to infection should favour tolerance when disease severity allows survival and host adaptation42. As European bats infected with P. destructans display no population-level effects, they are thought to tolerate infection, despite high fungal loads and almost 100% prevalence17,20,21. Host tolerance and/or disease resistance can be measured as a regression slope between health and pathogen load38,42.

Here, we report on host-pathogen interactions in the greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis), the European species showing highest skin infection intensity, based on blood parameters. We hypothesise that hibernating European bats are unable to maintain blood parameters within the normal physiological ranges found in healthy bats when exposed to the WNS fungal agent, and that blood homeostasis disruption could be related to infection intensity and hibernation temperature. We predict 1) a skin lesion threshold distinguishing healthy and diseased bats, 2) blood acidosis and a decrease of blood glucose in bats with high P. destructans infection intensity, and 3) a lower body mass index (BMI) in bats with blood homeostasis disruption. We also predict a reduced rate of BMI loss with increasing infection intensity, indicative of disease tolerance. An improved understanding of how hibernating bats optimise their health to survive pathogenic pressure will have positive ramifications for wildlife and conservation medicine.

Methods

Ethics statement

Each bat was handled in such a way as to minimise sampling distress and was released at the hibernaculum one hour after capture. Fieldwork and bat sampling was performed in accordance with Czech Law No. 114/1992 on Nature and Landscape Protection, based on permits 1662/MK/2012S/00775/MK/2012, 866/JS/2012 and 00356/KK/2008/AOPK issued by the Agency for Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic. Experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Czech Academy of Sciences (No. 169/2011). Sampling at the Nietoperek Natura 2000 site (Poland) was approved by the II Local Ethical Commission in Wrocław (No. 45/2015) and the Regional Nature Conservancy Management in Gorzów Wielkopolski (WPN-I-6205.10.2015.AI and WPN-I-6205.20.2016.AI). The authors were authorised to handle free-living bats under Czech Certificate of Competency No. CZ01341 (§17, Act No. 246/1992) and Polish Certificate of Competency in Experimental Procedures on Animals (Polish Laboratory Animal Science Association, Certificate No. 2413/2015).

Hibernacula studied

Seventy-nine bats were sampled at three important European hibernacula, the Nietoperek bunker (NIE; Poland), the Šimon and Juda mines (SJM; Czech Republic) and the Sloupsko-Šošůvské caves (SSC; Czech Republic), during the late hibernation period in 2015. Control sampling was undertaken at the Nietoperek bunker during March 2016 to evaluate infection dynamics. All three localities differ in geomorphology and microclimate conditions. No mass mortalities have been reported from any of the sites43–46 and numbers of hibernating M. myotis have remained stable, or have increased slightly over recent years.

The Nietoperek bat reserve lies in the underground corridors of an abandoned German military fortification from the central sector of the Międzyrzecz Fortified Front in western Poland (52°25′N, 15°32′E). The aboveground bunkers are connected by 3–4.5 m high and 2.5–4 m wide underground railway corridors. Sites preferred by hibernating M. myotis have a median temperature of 8.7 °C (min-max 6.1–9.9 °C), 100% relative humidity (min-max 77.5–100.0%) and 9 g/m3 absolute humidity (min-max 6–9 g/m3)46.

The Šimon and Juda mines comprise two gallery systems, the entrances of which open into a 10 m deep iron ore quarry. The mines were closed in 1870 and most galleries were flooded after World War I. While the galleries were drained between 1956 and 1957, no more mining took place. The lower gallery system has four horizontal storeys, each 2–2.5 m high, the upper system comprising an irregular labyrinth of galleries and chambers. Differences in geomorphology mean that each system has a different microclimate, the lower being colder, with temperatures rarely exceeding 5 °C (relative humidity close to 100%; absolute humidity 7–8 g/m3) and the upper having temperatures around 7 °C in most parts, though dropping close to the main entrance47.

The Sloupsko-Šošůvské caves comprise a natural karst system with 7 km of chasms, domes and corridors. The 8 m high and 20 m wide main entrance is located in the northern part of the cave. Due to their complicated geomorphology, microclimatic conditions vary widely. Hibernating bats mainly use those parts close to the main entrance (e.g. the Nicová and Eliška cave45) with mean annual temperatures fluctuating between 5.5 and 7.5 °C and an absolute humidity of 7–8 g/m3 48.

Measurements of bat health

The body surface temperature of each hibernating bat was measured using a Ryatek contactless laser thermometer (Total Temperature Instrumentation Inc.) prior to its removal from the hibernaculum wall. Each bat was then sexed and its age estimated based on epiphyseal ossification of the thoracic limb fingers and tooth abrasion49. Callipers were used to measure forearm length and body mass was determined using a portable top-loading balance. BMI was calculated as body mass (g) divided by left forearm length (mm)50.

After a re-warming period of 60 minutes, the skin was disinfected with alcohol and a blood sample (100 µl) taken from the uropatagial vessel using a heparinised tube51. An i-STAT portable clinical analyser (EC8+ diagnostic cartridge, Abaxis, Union City, CA, USA) was used to measure sodium (Na, mmol/L), potassium (K, mmol/L), chloride (Cl, mmol/L), total dissolved carbon dioxide (tCO2, mmol/L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN, mmol/L), glucose (GLU, mmol/L), haematocrit (Hct, L/L), pH, partial dissolved carbon dioxide (pCO2, kPa), bicarbonate (HCO3, mmol/L), base excess (BE, mmol/L), anion gap (AnGap, mmol/L) and haemoglobin (Hb, g/L).

A subsample was used to prepare a blood smear, which was then treated with Romanowsky stain. Differential white blood cell counts were determined by counting 100 leukocytes under oil immersion magnification and calculating the relative number of lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils.

Measurement of infection intensity

Immediately following capture, the surface of the left wing was swabbed (FLOQ Swabs, Copan Flock Technologies srl, Brescia, Italy) in a standardised manner to collect fungal biomass. Fungal load was calculated using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Halden, Germany) was used to isolate fungal DNA from the wing swabs. A dual-probe TaqMan (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to quantify P. destructans DNA (ng per left wing area; triplicate samples) using a previously described protocol employing positive and negative controls and a dilution series calibration curve from a positive control19,21,52,53. Suspected fungal growths from other parts of the body (e.g. ears, muzzle) were collected for laboratory culture examination12. Skin lesions were enumerated by photographing both wings over a 368 nm ultra-violet (UV) lamp19,21,54. A 4 mm punch biopsy, centred over the lesion, was collected from each bat to confirm P. destructans infection on histopathology22,23.

Statistical analysis

Normality of variable distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normally distributed variables were log transformed and rechecked. All parameters were normally distributed after transformation, with the exception of body surface temperature (W = 0.936, p = 0.005), haematocrit (W = 0.896, p < 0.001), haemoglobin (W = 0.896, p < 0.001) and percentage of eosinophils, monophils and basophils (Shapiro-Wilk tests, p < 0.001). In these cases, statistical analysis was conducted using non-parametric tests, i.e. the Kruskal-Wallis test, the Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman’s correlation. The slopes and intercepts of linear regressions were compared using the Student’s t-test.

Haematological parameters did not differ between age classes (adult vs. sub-adult) or sexes (ANOVA and t-test); hence, the data were pooled for subsequent analyses. We scored the level of wing damage based on the total number of UV-fluorescing skin lesions on both wings as: 1 = 0 to 50 lesions, 2 = 51 to 250 lesions, 3 = 251 to 500 lesions, 4 = 501 to 1000 lesions and 5 = more than 1000 lesions. Effect of locality and wing-lesion score on blood parameters was tested using general linear mixed models (GLMM) with locality (hibernaculum) set as a random effect. As blood parameters were highly inter-correlated, we used principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate inter-individual differences in distribution along axes linked with severity of skin infection, i.e. number of UV-fluorescing skin lesions.

Data on fungal load, number of UV-fluorescing skin lesions and blood parameters from Nietoperek (Poland), the Šimon and Juda mines (Czech Republic) and the Sloupsko-šošůvské caves (Czech Republic) are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Results

Relationship between number of skin lesions, body surface temperature, BMI and P. destructans load

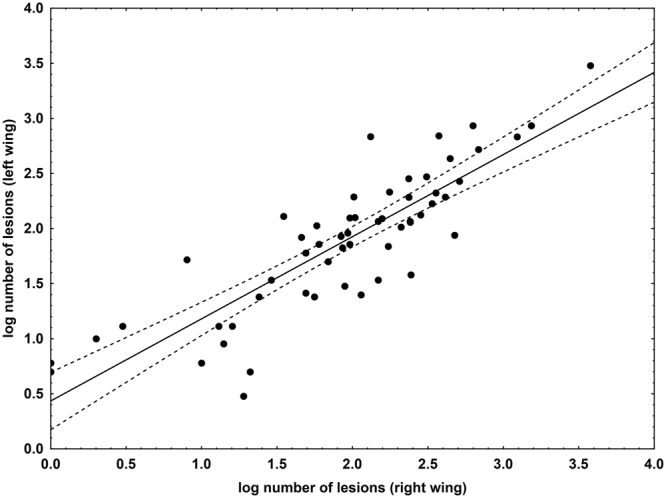

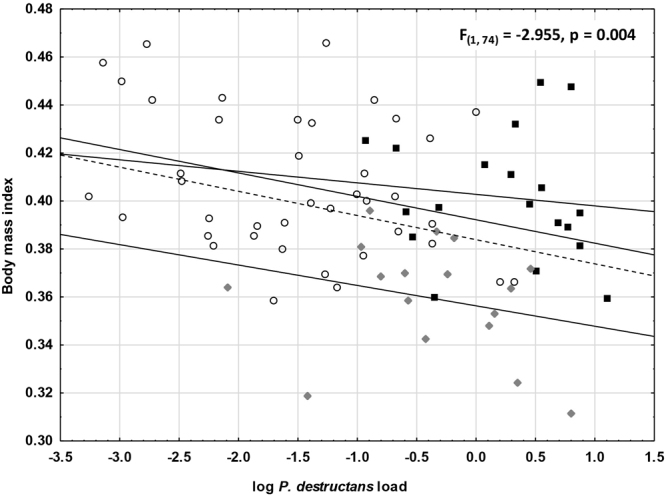

The number of skin lesions fluctuated between 0 and 3782. One wing for a given individual always had significantly more lesions (Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Test; Z = 2.497, p = 0.013; Fig. 1), though the number of lesions on each wing was correlated (Spearman rank order correlation rs = 0.857, p < 0.05). Consequently, we used the sum of UV-fluorescing lesions from both wings as it more precisely expressed total skin infection severity. Number of lesions was positively correlated with P. destructans load and negatively with body surface temperature (Table 1). The decline in BMI with higher P. destructans load was the same at all localities, though the regression curve for the Sloupsko-Šošůvské caves did not differ significantly at its lower intercept (SSC vs. NIE t = −0.303, DF = 53, p = 0.382; SSC vs. SJM t = −0.141, DF = 32, p = 0.445) due to the lowered BMI of hibernating bats (Figs 2 and 3). When material from all localities and both years of sampling was pooled, the decline in BMI with increasing P. destructans load and number of skin lesions became statistically significant (P. destructans load F(74) = −2.955, p = 0.004; UV-fluorescing skin lesions F(75) = −2.461, p = 0.016).

Figure 1.

Relationship between the number of skin lesions produced by P. destructans on the left and right wing of each bat. Displayed as a scatter plot of log-transformed data, it indicates a positive correlation between the left and right wing lesion counts. Points lying outside the 95% confidence intervals of the regression line show that one wing had more UV-fluorescing lesions than the contralateral wing in a given bat.

Table 1.

Spearman rank order correlation between body parameters and infection parameters.

| Variable | Number of skin lesions | Body surface temperature | Body mass index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body surface temperature | −0.54 | ||

| Body mass index | −0.15 | −0.07 | |

| P. destructans load | 0.69 | −0.61 | −0.12 |

Figures in bold are significantly different at α < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Relationship between BMI and P. destructans load for bats from different localities. F- and p-values are given to demonstrate the effect of P. destructans load on bat BMI in the pooled material. Dots = Nietoperek (NIE); squares = Šimon and Juda mine (SJM); diamonds = Sloupsko-šošůvské cave (SSC); dashed line = regression line for pooled dataset.

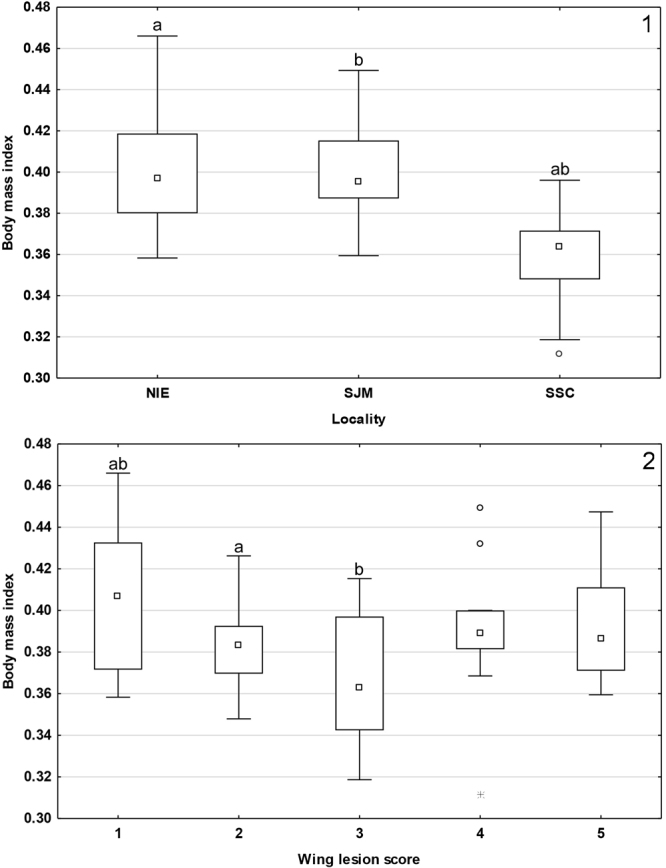

Figure 3.

Median BMI of bats from (1) different localities, and (2) with different wing-lesion scores. Midpoint = median, box = inter-quartile range, whiskers = non-outlier range, dots = outliers, stars = extremes. Groups marked with the same letter differ significantly.

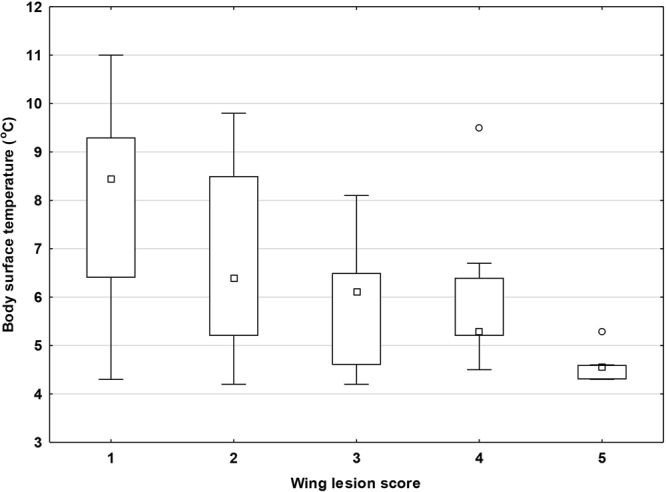

GLMM confirmed both the differences in P. destructans load (F = 8.106, p < 0.001) and BMI (F = 7.785, p < 0.001). While post-hoc univariate tests indicated locality as the main effect for P. destructans load; BMI was significantly influenced by both locality and wing-lesion score (Fig. 3). Highest BMI scores were recorded at lowest infection severity (score 1). Kruskal-Wallis tests confirmed a difference in body surface temperature for both locality (H(2, N = 57) = 49.826, p < 0.001) and wing-lesion score (H(4, N = 57) = 16.773, p = 0.002), hibernating bats with lowest body surface temperatures showing increased infection severity (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Body surface temperature of hibernating bats with different wing-lesion scores. Midpoint = median, box = inter-quartile range, whiskers = non-outlier range, dots = outliers. Body surface temperature was significantly different between wing-lesion scores (Kruskal-Wallis test: H4,57 = 16.773; p = 0.002).

Relationship of skin infection level to blood chemistry and haematology profile

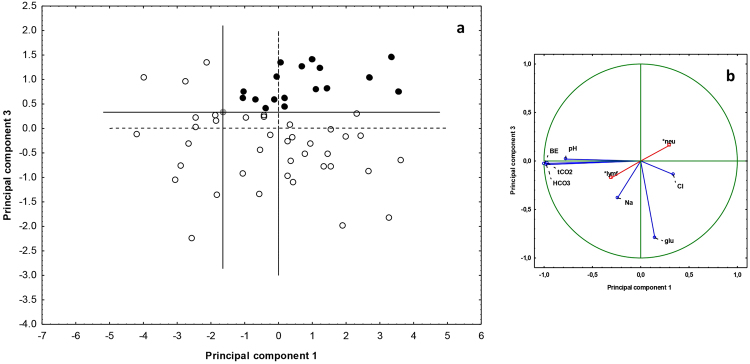

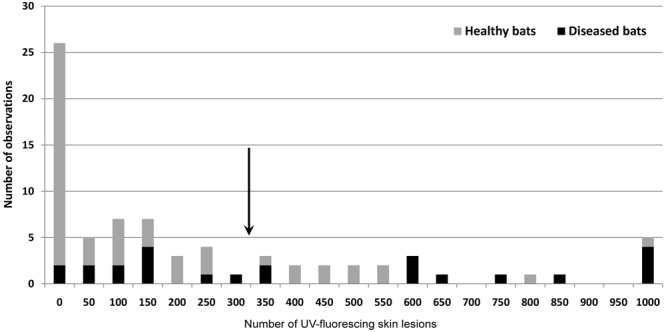

Nine blood parameters were significantly affected by locality and wing-lesion score (Tables 2 and 3), the GLMM model explaining between 14.3 and 37.7% of variability. We used seven continuous blood parameters (excluding percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes) for PCA analysis of samples from 2015, the first three components of which explained 92.5% of total variability. Acid-base variables (tCO2, pH, HCO3 and BE) displayed a strong negative correlation with the first component, electrolytes (Na and Cl) correlated positively with the second component and glucose negatively with the third component. The space defined by the first and third components provided the best separation between individuals (Fig. 5). Highest principal component values were observed in a single healthy individual (without UV-fluorescing skin lesions), its position subsequently being considered a new midpoint for the principal component axes. All individuals (n = 18) located in the upper right space were diagnosed with homeostasis disruption associated with skin infection, the three worst cases (top right position in Fig. 5) displaying infection intensities of 2394, 876 and 1490 lesions. As all bats from Nietoperek proved healthy, we took control samples during winter 2016 and repeated the PCA analysis with a larger sample size. While there was no difference in BMI and skin infection intensity in 2015 and 2016 (T-test; t = −1.598, p = 0.118, and t = 1.154, p = 0.256); P. destructans load was higher in 2015 than 2016 (T-test; t = 3.176, p = 0.003). PCA added seven new cases to those diagnosed with homeostasis disruption, including two from Nietoperek. Average number of skin lesions, P. destructans load, BMI and body surface temperature differed significantly between healthy and diseased bats (Table 4). We defined a theoretical breaking point (skin lesion threshold) for the manifestation of skin infection in disruption of blood parameters, based on the median between the 95% confidence intervals of the two groups (i.e. 328.5 skin lesions; Fig. 6). Six blood parameters differed between the groups defined by PCA; however, only glucose, skin lesion number, log P. destructans load and body surface temperature differed between the groups defined by the skin lesion threshold (Table 4).

Table 2.

Summary statistics for general linear models of blood parameters, with wing-lesion score as a fixed factor and locality as a random factor.

| Dependent Variable | Adjusted R2 | df Model | df Residual | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 0.143 | 6 | 52 | 2.609 | 0.028 |

| K | 0.059 | 6 | 52 | 1.602 | 0.165 |

| Cl | 0.158 | 6 | 50 | 2.749 | 0.022 |

| tCO2 | 0.342 | 6 | 51 | 5.946 | <0.001 |

| Urea | −0.019 | 6 | 51 | 0.823 | 0.558 |

| Glucose | 0.152 | 6 | 51 | 2.705 | 0.023 |

| pH | 0.259 | 6 | 51 | 4.314 | 0.001 |

| pCO2 | 0.072 | 6 | 51 | 1.739 | 0.131 |

| HCO3 | 0.348 | 6 | 51 | 6.061 | <0.001 |

| Base excess | 0.377 | 6 | 51 | 6.746 | <0.001 |

| Anion gap | 0.005 | 6 | 46 | 1.045 | 0.409 |

| Neutrophils | 0.245 | 6 | 52 | 4.145 | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.254 | 6 | 52 | 4.289 | 0.001 |

Figures in bold are significantly different at α < 0.05.

Table 3.

Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test of locality and wing-lesion score impact on blood parameters.

| Variable | Wing-lesion score | Locality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | df | n | p | H | df | n | p | |

| Haematocrit | 2.613 | 4 | 58 | 0.625 | 0.222 | 2 | 58 | 0.895 |

| Haemoglobin | 2.613 | 4 | 58 | 0.625 | 0.222 | 2 | 58 | 0.895 |

| Eosinophils | 0.756 | 4 | 59 | 0.944 | 5.242 | 2 | 59 | 0.073 |

| Monocytes | 1.382 | 4 | 59 | 0.847 | 3.201 | 2 | 59 | 0.202 |

| Basophils | 1.400 | 4 | 59 | 0.844 | 0.025 | 2 | 59 | 0.988 |

Figure 5.

(a) Bat dispersion and (b) projection of variables in blood parameter space based on PCA. The position of bats with no UV-fluorescing skin lesions and highest principal component values (grey dot) was used to define the midpoint of new principal component axes. Black dots = diseased, open dots = healthy; supplementary factors are marked by a star. Abbreviations: BE = base excess, glu = glucose, lymf = lymphocytes, neu = neutrophils.

Table 4.

Difference between healthy and diseased hibernating bats in groups defined by a) principal component analysis (PCA) and b) UV spot threshold (total UV-fluorescing skin lesion number = 328.5).

| Variables | Groups defined by PCA | Groups defined by skin lesion threshold | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean healthy | Mean diseased | t | df | p | Mean healthy | Mean diseased | t | df | p | |

| Na | 154.177 | 151.333 | 1.521 | 73 | 0.133 | 153.811 | 151.955 | 0.961 | 73 | 0.340 |

| K | 6.62 | 7.1125 | −1.564 | 73 | 0.122 | 6.738 | 6.873 | −0.412 | 73 | 0.682 |

| Cl | 122.647 | 124.083 | −0.756 | 73 | 0.452 | 122.962 | 123.455 | −0.252 | 73 | 0.802 |

| tCO2 | 24.902 | 22.958 | 2.109 | 73 | 0.038 | 24.698 | 23.273 | 1.488 | 73 | 0.141 |

| Urea | 20.492 | 24.217 | −1.903 | 73 | 0.061 | 20.862 | 23.664 | −1.381 | 73 | 0.171 |

| Glucose | 7.102 | 4.521 | 5.599 | 73 | <0.001 | 6.700 | 5.255 | 2.683 | 73 | 0.009 |

| Haematocrit | 55.177 | 57.083 | −1.799 | 73 | 0.076 | 55.717 | 55.955 | −0.214 | 73 | 0.831 |

| pH | 7.294 | 7.249 | 3.037 | 73 | 0.003 | 7.286 | 7.262 | 1.540 | 73 | 0.128 |

| pCO2 | 6.415 | 6.558 | −0.646 | 73 | 0.52 | 6.474 | 6.431 | 0.190 | 73 | 0.850 |

| HCO3 | 23.477 | 21.471 | 2.215 | 73 | 0.03 | 23.223 | 21.9 | 1.398 | 73 | 0.166 |

| Base excess | −3.059 | −5.833 | 2.599 | 73 | 0.011 | −3.453 | −5.136 | 1.495 | 73 | 0.139 |

| Anion gap | 14.813 | 13.238 | 2.260 | 67 | 0.027 | 14.500 | 13.895 | 0.817 | 67 | 0.417 |

| Haemoglobin | 187.549 | 194.083 | −1.811 | 73 | 0.074 | 189.415 | 190.182 | −0.203 | 73 | 0.840 |

| Neutrophils | 32.114 | 38.455 | −1.346 | 55 | 0.184 | 31.974 | 39.737 | −1.607 | 55 | 0.114 |

| Lymphocytes | 67.371 | 59.864 | 1.616 | 55 | 0.112 | 67.184 | 59.053 | 1.699 | 55 | 0.096 |

| Eosinophils | 0.457 | 1.273 | −2.800 | 55 | 0.007 | 0.658 | 1.000 | −1.075 | 55 | 0.288 |

| Monocytes | 0.286 | 0.364 | −0.319 | 55 | 0.751 | 0.368 | 0.211 | 0.628 | 55 | 0.533 |

| Basophils | 0.114 | 0.046 | 0.579 | 55 | 0.565 | 0.132 | 0.000 | 1.080 | 55 | 0.285 |

| Body surface temperature | 7.906 | 5.933 | 4.326 | 72 | <0.001 | 7.698 | 6.176 | 3.042 | 72 | 0.003 |

| Body mass index | 0.401 | 0.382 | 2.338 | 73 | 0.022 | 0.397 | 0.390 | 0.900 | 73 | 0.371 |

| log P. destructans load | −1.102 | −0.186 | −3.584 | 71 | <0.001 | −1.168 | 0.064 | −5.033 | 71 | <0.001 |

Figures in bold are significantly different at α < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Frequency of skin lesions. Bats were identified as either healthy (n = 52) or with homeostasis disrupted by P. destructans skin infection (n = 24) using PCA. The arrow shows the expected threshold in number of UV-fluorescing skin lesions (328.5) for manifestation of skin infection through disruption of blood parameters.

Discussion

The continent-wide colonisation of Palearctic underground hibernacula and ongoing spread of the fungal pathogen in North America makes exposure of bats hibernating in the temperate zone of the northern hemisphere to P. destructans highly probable11,16,17,20,21,55–58. The wide distribution of both the host and its pathogen results in spatial and temporal variation in host-pathogen population interactions, allowing performance studies into host health and pathogen virulence under differing environmental conditions. Here we show that even early-stage fungal damage of bat wing membranes may negatively impact physiological status, dependent on infection intensity and hibernation conditions. Our data suggest that the pattern of disease impact can vary between sites.

We chose European M. myotis as a model species to examine naturally occurring host-pathogen interactions with P. destructans as they have a higher survival capacity than the North American little brown bat (M. lucifugus) and big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus)59. Nevertheless, sporadic mortalities associated with P. destructans infection have been reported for M. myotis, documenting that infection intensity can range from mild to severe18. Recently, a model taking account of temperature, humidity-dependent fungal growth and bat energetics during hibernation was devised, which predicted that the likelihood of surviving P. destructans infection increases with increasing body size and drier and/or colder hibernation sites59. While M. myotis is one of the largest European bat species, highest infection intensity has been found in those hibernating at low hibernation body temperatures, contrary to our prediction. Three hypotheses may explain this paradox. First, bats select lower hibernation temperatures as an adaptation to conserve energy when dealing with high infection intensity. Second, bats selecting low hibernation temperatures develop increased infection intensities as a consequence of a reduced ability to up-regulate immune functions and clear the infection24,60,61. Third, under conditions of natural infection, P. destructans growth and virulence is stronger in those bats hibernating at low temperatures, despite laboratory studies suggesting a temperature optimum of between 12.5 and 15.8 °C62. Unfortunately, we lack data on hibernation temperature history, arousal frequency, infection dose and duration of infection for each bat, which would allow these hypotheses to be tested explicitly. In the present study, bats were only sampled once at the end of the hibernation period. Interestingly, skin lesion number differed between the left and right wings, suggesting differing exposure to infection and uneven spread of the fungal agent across the body surface during cleaning when aroused. A field experiment analysing fungal load dynamics in relation to wing membrane pathology and bat body temperature during hibernation is needed to provide greater insight into such host-pathogen interactions under natural conditions.

BMI loss in diseased bats indicative of disease tolerance

Our data provide further evidence for tolerance of Palearctic bat species to the P. destructans fungus21. The regression lines obtained by plotting host BMI against pathogen burden (skin fungal load) at each hibernaculum display a shallow BMI loss slope as infection intensity increases (Fig. 2). Owing to the differences in origin of the hibernacula used in this study, host-pathogen population interactions will have undergone different evolutionary histories, ranging from tens, to hundreds or even thousands of years. Cave-hibernating bats, with their distinctly lower BMI (Fig. 2), showed lowest tolerance capacity to infection. Transition to euthermia in the early post-hibernation period allows bats to mount an effective immune response against the fungal pathogen and clear any skin infection19,63. Later, the bat’s defence strategy turns from tolerance to resistance42. Very little is known about the health of P. destructans infected hosts in the period following emergence from hibernation. The dichotomy of disease outcome in euthermic bats results in either healing63 or mortality due to immunopathology64. In M. myotis, healing may occur within two weeks, during which the diagnostic UV-fluorescence disappears and a scab develops over the previously infected skin19. The costs of neutrophilic inflammation and wing membrane tissue remodelling are hard to estimate. Likewise, we lack detailed quantification of physiological costs associated with flight performance and changes in foraging efficiency in bats recovering from P. destructans infection63,65–67. Upon arousal, early euthermic females may also face a trade-off between mounting an immune response and the energetic investment needed to initiate gestation68,69. Higher cortisol levels, indicative of chronic stress, have been recorded in bats surviving exposure to P. destructans, and this may have adverse effects on reproductive success70. Further, North American species recovering from P. destructans infection have shown shifts in pregnancy and lactation, suggestive of reproductive fitness consequences71. Similar studies on reproductive fitness consequences have yet to be performed on European bats facing fungal pathogen pressure.

Alterations in blood homeostasis in diseased bats

While infectious diseases are commonly thought to induce biochemical responses that differ between species72, our data showed hibernation site-specific differences. Haematology and blood chemistry reflect body and tissue status. A range of mechanisms maintain blood parameters within a narrow range; blood pH, for example, being maintained through respiratory system and kidney function. Hibernation, on the other hand, represents a specific physiological state resulting in changes to metabolic and biochemical pathways73. Heart rate, cardiac output and respiration are greatly reduced during deep hibernation, and these changes lead to a drop in pH and marked acidosis.

Studies of blood homeostasis in M. lucifugus indicate a pattern of changes dependent on WNS intensity29,31,32,74. While such studies have sampled blood by decapitation, we used non-lethal vessel puncturing to study M. myotis, a strictly protected European bat. Cryan et al.31, using data on P. destructans infection in both captive and wild hibernating bats, noted that electrolyte depletion increased with increasing wing damage severity. Furthermore, measurements of urine-specific gravity suggested that bats underwent hypotonic dehydration. In a second study, captive hibernation of M. lucifugus following experimental inoculation with P. destructans complicated blood sampling, allowing analysis of only eight infected bats32. The addition of data from two follow-up captive inoculation experiments, however, showed no difference between the infected and control groups68. While data obtained by Warnecke et al.32 were only suggestive of metabolic acidosis, Verant et al.29 observed chronic respiratory acidosis with metabolic compensation in bats at an early stage of the disease.

A skin lesion threshold distinguishing healthy and diseased bats

As all bats in our study were naturally infected in their hibernacula and confirmed positive for P. destructans (with the exception of one individual from Nietoperek), it was not possible to compare host physiological responses to the fungus against a non-infected control group. Nevertheless, our non-diseased and diseased groups, as defined by PCA, differed in blood pH, tCO2, bicarbonate, base excess/deficit and anion gap. These acid-base parameters shifted to mild metabolic acidosis in the diseased group (Table 4). The diseased group displayed higher infection intensity, distinguished by both fungal load and UV-fluorescing skin lesions. Bats defined as diseased (i.e. with blood parameters showing homeostasis disruption) had a hibernating body surface temperature around 2 °C lower than non-diseased individuals. The diseased group also displayed significantly decreased glucose concentrations and BMI. Contrary to blood biochemistry results for M. lucifugus, we observed no differences in electrolytes between diseased and non-diseased M. myotis, suggesting that the acid-base disruption was due to increased energy utilisation associated with infection. The increase in differential neutrophil count was non-significant, probably because the white blood cells migrated from blood to the infected sites19. Interestingly, significant eosinophilia was observed in diseased M. myotis. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is commonly associated with chronic, parasitic and fungal infections75. As eosinophilia is also associated with hypersensitivity reactions, however, our findings may support the hypothesis that immunopathology plays a role in post-emergent WNS mortality64.

While exposure of bats to multiple natural and/or anthropogenic stressors is a realistic environmental scenario76–79, sub-lethal adverse effects are mostly underreported. Disease pathogenesis and the action of multiple stressors during hibernation are not yet fully understood; however, different stressors may well combine to exert synergistic effects80. Importantly, disturbance by human activities, such as tourism, caving or research, could also threaten hibernating bats by increasing energy expenditure81.

Conclusion

Following the emergence of WNS and recognition of its impact on North American bat populations in 2006, chiropterologists concerned with European bat conservation have asked one essential question: are Palearctic bat populations and communities threatened by this fungal disease? Up to now, there have been no functional studies addressing host-pathogen interactions in relation to WNS. However, there is mounting evidence for virulent skin invasion and pathognomonic lesions in many hibernating Eurasian bat species. As these findings have not been associated with mass mortalities and/or population declines, research should be directed toward examining health consequences in terms of trade-off mechanisms modulating investment into host response to infection.

In this study, we were able to show variation in fungal pathogen pressure in relation to hibernaculum-dependent physiological effects of P. destructans infection. We conclude that European M. myotis survive P. destructans invasion, despite showing deterioration in health, with infection intensity dependent on hibernation conditions. Disruption in blood homeostasis was observed in bats, even with a low threshold number of skin lesions on both wings. We argue that overwintering in underground hibernacula colonised by this virulent pathogen is associated with health-related costs for European bats. Further research should aim to quantify levels of homeostasis disruption in terms of constrained energy reserves and compatibility for survival.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported through Czech Science Foundation Grant No. 17-20286S and Grant No. 221/2016/FVHE of the Internal Grant Agency of the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences Brno. We thank Natália Martínková for measuring the fungal load of infected bats and for valuable comments on the original manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Kevin Roche for correcting and improving the English text.

Author Contributions

H.Bandouchova, J.P. and J.Z. conceived the idea and designed the methodology; H.Bandouchova, T.B., H.Berkova, J.B., T.K., V.K., P.L., V.P., J.P., A.Z. and J.Z. collected data; V.K., A.Z. and J.P. conducted the laboratory analysis; H.Bandouchova, J.P. and J.Z. analysed the data; H.Bandouchova, J.P. and J.Z. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critical comments on earlier drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-24461-5.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Graham AL, et al. Fitness consequences of immune responses: strengthening the empirical framework for ecoimmunology. Funct. Ecol. 2011;25:5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01777.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos. 2000;88:87–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheldon BC, Verhulst S. Ecological immunology: costly parasite defences and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol. & Evol. 1996;11:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stearns SC. Life-history tactics: a review of the ideas. Q. Rev. Biol. 1976;51:3–47. doi: 10.1086/409052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantini D, Møller AP. Does immune response cause oxidative stress in birds? A meta-analysis. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 2009;153:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris K, Evans MR. Ecological immunology: life history trade-offs and immune defense in birds. Behav. Ecol. 2000;11:19–26. doi: 10.1093/beheco/11.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turbill C, Bieber C, Ruf T. Hibernation is associated with increased survival and the evolution of slow life histories among mammals. P. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2011;278:3355–3363. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphries MM, Thomas DW, Speakman JR. Climate-mediated energetic constraints on the distribution of hibernating mammals. Nature. 2002;418:313–316. doi: 10.1038/nature00828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore MS, et al. Energy conserving thermoregulatory patterns and lower disease severity in a bat resistant to the impacts of white-nose syndrome. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2018;188:163–176. doi: 10.1007/s00360-017-1109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cryan P, Meteyer C, Boyles J, Blehert D. Wing pathology of white-nose syndrome in bats suggests life-threatening disruption of physiology. BMC Biol. 2010;8:135. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blehert DS, et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science. 2009;323:227. doi: 10.1126/science.1163874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gargas A, Trest MT, Christensen M, Volk TJ, Blehert DS. Geomyces destructans sp nov associated with bat white-nose syndrome. Mycotaxon. 2009;108:147–154. doi: 10.5248/108.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick WF, et al. An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common North American bat species. Science. 2010;329:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1188594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorch JM, et al. Experimental infection of bats with Geomyces destructans causes white-nose syndrome. Nature. 2011;480:376–378. doi: 10.1038/nature10590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman JTH, Reichard JD. Bat white-nose syndrome in 2014: A brief assessment seven years after discovery of a virulent fungal pathogen in North America. Outlooks on Pest Management. 2014;25:374–377. doi: 10.1564/v25_dec_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorch JM, et al. First detection of bat white-nose syndrome in Western North America. mSphere. 2016;1:e00148–16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00148-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínková N, et al. Increasing incidence of Geomyces destructans fungus in bats from the Czech Republic and Slovakia. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pikula J, et al. Histopathology confirms white-nose syndrome in bats in Europe. J. Wildlife Dis. 2012;48:207–211. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-48.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pikula J, et al. White-nose syndrome pathology grading in Nearctic and Palearctic bats. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0180435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zukal J, et al. White-nose syndrome fungus: a generalist pathogen of hibernating bats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zukal J, et al. White-nose syndrome without borders: Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection tolerated in Europe and Palearctic Asia but not in North America. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2016;6:19829. doi: 10.1038/srep19829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandouchova H, et al. Pseudogymnoascus destructans: Evidence of virulent skin invasion for bats under natural conditions, Europe. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015;62:1–5. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meteyer CU, et al. Histopathologic criteria to confirm white-nose syndrome in bats. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2009;21:411–414. doi: 10.1177/104063870902100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Field KA, et al. The white-nose syndrome transcriptome: activation of anti-fungal host responses in wing tissue of hibernating little brown myotis. PLoS Pathol. 2015;11:e1005168. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mascuch SJ, et al. Direct detection of fungal siderophores on bats with white-nose syndrome via fluorescence microscopy-guided ambient ionization mass spectrometry. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donoghue AJ, et al. Destructin-1 is a collagen-degrading endopeptidase secreted by Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the causative agent of white-nose syndrome. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:7478–7483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507082112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flieger M, et al. Vitamin B2 as a virulence factor in Pseudogymnoascus destructans skin infection. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2016;6:33200. doi: 10.1038/srep33200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blehert DS. Fungal disease and the developing story of bat white-nose syndrome. PLoS Pathol. 2012;8:e1002779. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verant ML, et al. White-nose syndrome initiates a cascade of physiologic disturbances in the hibernating bat host. BMC Physiol. 2014;14:10. doi: 10.1186/s12899-014-0010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeder DM, et al. Frequent arousal from hibernation linked to severity of infection and mortality in bats with white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cryan PM, et al. Electrolyte depletion in white-nose syndrome bats. J. Wildlife Dis. 2013;49:398–402. doi: 10.7589/2012-04-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warnecke L, et al. Pathophysiology of white-nose syndrome in bats: a mechanistic model linking wing damage to mortality. Biol. Letters. 2013;9:20130177. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warnecke L, et al. Inoculation of bats with European Geomyces destructans supports the novel pathogen hypothesis for the origin of white-nose syndrome. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:6999–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200374109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campana MG, et al. White-Nose Syndrome Fungus in a 1918 Bat Specimen from France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1611–1612. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.170875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zahradníková, A. J. et al. Historic and geographic surveillance of Pseudogymnoascus destructans possible from collections of bat parasites. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 65, 303-308 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Leopardi S, Blake D, Puechmaille SJ. White-Nose Syndrome fungus introduced from Europe to North America. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:R217–R219. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drees KP, et al. Phylogenetics of a Fungal Invasion: Origins and Widespread Dispersal of White-Nose Syndrome. mBio. 2017;8:e01941–01917. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01941-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider DS, Ayres JS. Two ways to survive infection: what resistance and tolerance can teach us about treating infectious diseases. Nat. Review Immunol. 2008;8:889–895. doi: 10.1038/nri2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raberg L, Graham AL, Read AF. Decomposing health: tolerance and resistance to parasites in animals. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B. 2009;364:37–49. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Behnke JM, Barnard CJ, Wakelin D. Understanding chronic nematode infections: Evolutionary considerations, current hypotheses and the way forward. Int. J. Parasitol. 1992;22:861–907. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90046-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kutzer MAM, Armitage SAO. Maximising fitness in the face of parasites: a review of host tolerance. Zoology. 2016;119:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urbanczyk, Z. Significance of the Nietoperek Reserve for Central European populations of Myotis myotis (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in Prague Studies in Mammalogy (eds. Horáček, I. & Vohralík, V.) 213–215 (Charles University Press, 1992).

- 44.Řehák Z, Gaisler. J. Long-term changes in the number of bats in the largest man-made hibernaculum of the Czech Republic. Acta Chiropterol. 1999;1:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zukal J, Řehák Z, Kovařík M. Bats of the Sloupsko-šošůvské cave (Moravian Karst, Central Moravia) Lynx. 2003;34:205–220. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kokurewicz T, Ogórek R, Pusz W, Matkowski K. Bats increase the number of cultivable airborne fungi in the “Nietoperek” bat reserve in western Poland. Microb. Ecol. 2016;72:36–48. doi: 10.1007/s00248-016-0763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Řehák Z, Gaisler J. Bats wintering in the abandoned mines under the Jelení road near Malá Morávka in the Jeseníky Mts (Czech Republic) Vespertilio. 2001;5:265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hebelka, J. & Rožnovský, J. (eds). Stanovení závislosti jeskynního mikroklimatu na vnějších klimatických podmínkách ve zpřístupněných jeskyních České republiky [Determination of cave microclimate dependence on external climatic conditions in accessible caves of the Czech Republic]. Acta Speleologica3, (2011). (in Czech).

- 49.Brunet-Rossinni, A. K. & Wilkinson, G. S. Methods for age estimation and the study of senescence in bats in Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats (eds Kunz, T. H. & Parsons, S.) 315–325 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

- 50.Kunz TH, Wrazen JA, Burnett CD. Changes in body mass and fat reserves in pre-hibernating little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) Ecoscience. 1998;5:8–17. doi: 10.1080/11956860.1998.11682443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pikula J, et al. Reproduction of rescued vespertilionid bats (Nyctalus noctula) in captivity: veterinary and physiologic aspects. Vet. Clin. N. Am.: Exotic Animal Practice. 2017;20:665–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shuey MM, Drees KP, Lindner DL, Keim P, Foster JT. Highly sensitive quantitative PCR for the detection and differentiation of Pseudogymnoascus destructans and other Pseudogymnoascus species. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2014;80:1726–1731. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02897-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lučan RK, et al. Ectoparasites may serve as vectors for the white-nose syndrome fungus. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:16. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1302-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turner GG, et al. Nonlethal screening of bat-wing skin with the use of ultraviolet fluorescence to detect lesions indicative of white-nose syndrome. J. Wildlife Dis. 2014;50:566–573. doi: 10.7589/2014-03-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puechmaille SJ, et al. Pan-european distribution of white-nose syndrome fungus (Geomyces destructans) not associated with mass mortality. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wibbelt G, et al. White-nose syndrome fungus (Geomyces destructans) in bats, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:1237–1243. doi: 10.3201/eid1608.100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zukal, J., Berková, H., Banďouchová, H., Kovacova, V. & Pikula, J. Bats and caves: activity and ecology of bats wintering in caves. In: Cave Investigation (eds Karabulut, S. & Cinku, M. C.), InTech, Rijeka, (2017).

- 58.Hoyt JR, et al. Widespread bat white-nose syndrome fungus, Northeastern China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:140. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayman DTS, Pulliam JRC, Marshall JC, Cryan PM, Webb CT. Environment, host, and fungal traits predict continental-scale white-nose syndrome in bats. Science Advances. 2016;2:e1500831. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lilley TM, et al. Immune responses in hibernating little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) with white-nose syndrome. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2017;284:8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore MS, et al. Hibernating Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus) Show Variable Immunological Responses to White-Nose Syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verant ML, Boyles JG, Waldrep W, Jr., Wibbelt G, Blehert DS. Temperature-Dependent Growth of Geomyces destructans, the Fungus That Causes Bat White-Nose Syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meteyer CU, et al. Recovery of little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) from natural infection with Geomyces destructans, white-nose syndrome. J. Wildlife Dis. 2011;47:618–626. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-47.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meteyer CU, Barber D, Mandl NJ. Pathology in euthermic bats with white nose syndrome suggests a natural manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Virulence. 2012;3:583–588. doi: 10.4161/viru.22330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reichard JD, Kunz TH. White-nose syndrome inflicts lasting injuries to the wings of little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) Acta Chiropterol. 2009;11:457–464. doi: 10.3161/150811009X485684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fuller NW, et al. Free-ranging little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) heal from wing damage associated with white-nose syndrome. EcoHealth. 2011;8:154–162. doi: 10.1007/s10393-011-0705-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voigt CC. Bat flight with bad wings: Is flight metabolism affected by damaged wings? J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:1516–1521. doi: 10.1242/jeb.079509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Speakman JR. The physiological costs of reproduction in small mammals. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B. 2008;363:375–398. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jonasson KA, Willis CKR. Changes in body condition of hibernating bats support the thrifty female hypothesis and predict consequences for populations with white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davy CM, et al. Conservation implications of physiological carry-over effects in bats recovering from white-nose syndrome. Conserv. Biol. 2017;31:615–624. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Francl KE, Ford WM, Sparks DW, Brack VJ. Capture and reproductive trends in summer bat communities in West Virginia: Assessing the impact of white-nose syndrome. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 2012;3:33–42. doi: 10.3996/062011-JFWM-039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bandouchova H, et al. Tularemia induces different biochemical responses in BALB/c mice and common voles. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009;9:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyer B, Barnes B. Molecular and metabolic aspects of mammalian hibernation expression of the hibernation phenotype results from the coordinated regulation of multiple physiological and molecular events during preparation for and entry into torpor. BioScience. 1999;49:713–724. doi: 10.2307/1313595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGuire LP, et al. White-nose syndrome disease severity and a comparison of diagnostic methods. EcoHealth. 2016;13:60–71. doi: 10.1007/s10393-016-1107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simons CM, Stratton CW, Kim AS. Peripheral blood eosinophilia as a clue to the diagnosis of an occult Coccidioides infection. Hum. Pathol. 2011;42:449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pikula J, et al. Heavy metals and metallothionein in vespertilionid bats foraging over aquatic habitats in the Czech Republic. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010;29:501–506. doi: 10.1002/etc.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bayat S, Geiser F, Kristiansen P, Wilson SC. Organic contaminants in bats: trends and new issues. Environ. Int. 2014;63:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Secord AL, et al. Contaminants of emerging concern in bats from the northeastern United States. Arch. Environ. Con. Tox. 2015;69:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s00244-015-0196-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zukal J, Pikula J, Bandouchova H. Bats as bioindicators of heavy metal pollution: history and prospect. Mamm. Biol. 2015;80:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.mambio.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Holmstrup M, et al. Interactions between effects of environmental chemicals and natural stressors: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:3746–3762. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Speakman JR, Webb PI, Racey PA. Effects of disturbance on the energy expenditure of hibernating bats. J. Appl. Ecol. 1991;28:1087–1104. doi: 10.2307/2404227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.