Abstract

Plastid engineering offers an important tool to fill the gap between the technical and the enormous potential of microalgal photosynthetic cell factory. However, to date, few reports on plastid engineering in industrial microalgae have been documented. This is largely due to the small cell sizes and complex cell-wall structures which make these species intractable to current plastid transformation methods (i.e., biolistic transformation and polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation). Here, employing the industrial oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica as a model, an electroporation-mediated chloroplast transformation approach was established. Fluorescent microscopy and laser confocal scanning microscopy confirmed the expression of the green fluorescence protein, driven by the endogenous plastid promoter and terminator. Zeocin-resistance selection led to an acquisition of homoplasmic strains of which a stable and site-specific recombination within the chloroplast genome was revealed by sequencing and DNA gel blotting. This demonstration of electroporation-mediated chloroplast transformation opens many doors for plastid genome editing in industrial microalgae, particularly species of which the chloroplasts are recalcitrant to chemical and microparticle bombardment transformation.

Keywords: Nannochloropsis, plastid transformation, oleaginous microalga, green fluorescent protein, photosynthetic cell factory

Introduction

Microalga-based biochemical factory is regarded as an ideal strategy for sequestering greenhouse gas and producing valuable molecules ranging from therapeutic proteins to biofuels (Tran et al., 2013; Moody et al., 2014). However, few natural strains exhibit the demanding traits as feedstock for biofuel production which have led to a quest for more specific genomic and biological models (Scott et al., 2010; Ge et al., 2014). Nannochloropsis spp. have attracted sustained interest from algal biofuels researchers owing to their rapid growth, high amounts of triacylglycerol (TAG) and high-value polyunsaturated fatty acid (FA) and their successful cultivation at large scale using natural sunlight by multiple institutes and companies (Radakovits et al., 2012; Vieler et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012, 2014; Corteggiani Carpinelli et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014a,b; Moody et al., 2014; Lu and Xu, 2015; Ajjawi et al., 2017; Wei H. et al., 2017; Zienkiewicz et al., 2017).

Genetic engineering of industrial microalgae provides a viable way to optimize crucial traits for commercial feedstock development (Gimpel et al., 2013; Zhang and Hu, 2014; Wang et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2018). A nuclear transformation method has been developed for Nannochloropsis sp. (Kilian et al., 2011; Vieler et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Iwai et al., 2015; Kang et al., 2015; Poliner et al., 2017; Xin et al., 2017), which facilitates the manipulation of crucial nodes in oil biosynthesis and the development of the RNA interference (RNAi) (Wei L. et al., 2017) and CRISPR/Cas9 methods (Wang et al., 2016). However, the plastome genetic engineering tools are not yet avaiable for Nannochloropsis spp. There are considerable attractions associated with placing transgenes into the plastid genome rather than the nuclear genome (Bock, 2014; Doron et al., 2016), particularly where plastid genomes are engineered to express valuable proteins (e.g., therapeutics proteins) (Tran et al., 2013): (i) high transgene expression levels; (ii) capacity for expressing multigene in artificial operons; (iii) devoid of gene silencing and other epigenetic mechanisms; (iv) higher precise insertion site than nuclear expression (which normally integrate foreign DNA into their nuclear genomes by non-homologous recombination).

Besides the manipulation of plastid genes (with a number of ~100) (Wei et al., 2013), transplastomic technology may utilized to express heterologous genes or gene clusters with economic values (e.g., pharmaceutical proteins) (Mayfield et al., 2007; Rasala et al., 2010). Moreover, ~10% of the nuclear gene products (mainly FA biosynthetic enzymes and photosynthesis related proteins which determine the key features of oleaginous microalgae for biofuel production) are targeted to plastids (Leister, 2003). This further expands the plastome engineering gene repertoire. Thus, transplastomic technology provided fundamental opportunities for rational trait-improvement of microalgae (Bock, 2014).

Although progresses have been made for several reference plants, plastid transformation is still restricted to a relatively small number of species (Bock, 2014). This is mainly due to the fastidious requirements in cell handling to match the methods currently available for plastid transformation (Maliga, 2004). For instance, although microparticle bombardment is a rountine pratice to delivery exogenous DNA into plant or microalgal plastids, it has a rigid requirement to cell diameters of target species (Cui et al., 2014). Genetic manipulation of chloroplasts of small-size microalgal species is intractable due to the limitation of availablity of golden particles (of which the smallest diameter is 0.6 μm). Therefore, biolistic plastid transformation have only been developed for a few micoalgal species (exclusively for species with relatively large cell sizes and huge chloroplasts), e.g., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (with a diameter of ~10 μm) (Boynton et al., 1988), red alga Porphyridium sp. (with a diameter of ~15 μm) (Lapidot et al., 2002) and green alga Platymonas subcordiformis (with a diameter of ~15 μm) (Cui et al., 2014). However, as for most industrial microalgal species of which the diameters are approximately a few microns (e.g., Nannochloropsis sp. and Chlorella sp., both with a diameter of ~2 μm), plastome genetic engineering tools have not yet been developed. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatment of protoplasts provides an alternative way for chloroplast transformation (Golds et al., 1993). However, as all protoplast-based methods, PEG-mediated protoplast transformation requires removal of the cell wall prior to transformation (or, alternatively, use of cell wall-deficient mutant strains), which makes the procedures technically demanding, labor intensive, and time consuming (Bock, 2015). Even worse, protoplast preparation is always intractable to most microalgal species of which the cell wall is complex (Maliga and Bock, 2011). Therefore, research and development of plastid biotechnology remain challenge for most industrial microalgae.

During the creation of nuclear mutagenesis library for industrial oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica, we found that antibiotic constructs were inserted into the plastid genome by electroporation. A similar phenomenon has also been documented in C. reinhardtii (Zhang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). Therefore, to probe the potential of applying electroporation in chloroplast transformation, employing N. oceanica as a model, a simple and rapid approach for chloroplast transformation was developed for N. oceanica.

Materials and methods

Gene cloning and vector construction

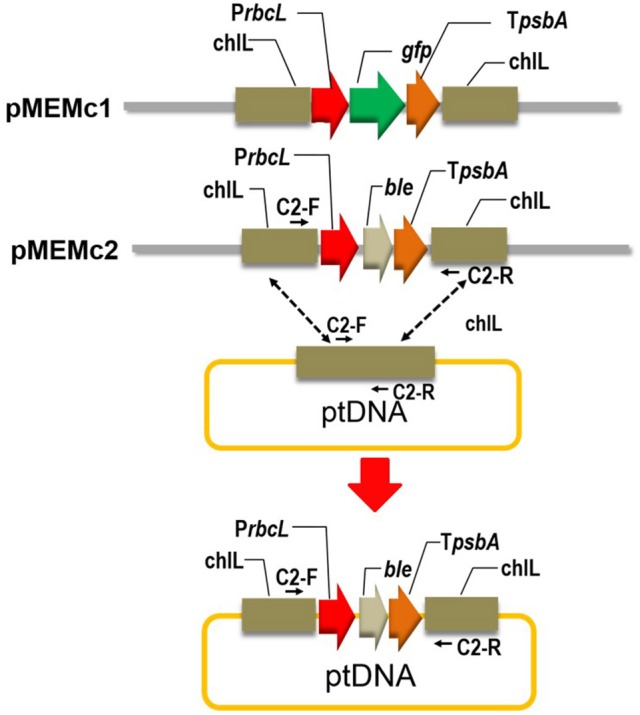

Genomic DNA was extracted using Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Omega, China) following a described procedure (Lu et al., 2009, 2010). N. oceanica endogenous chlL gene fragments, rbcL promoter and psbA terminator were amplified using sequence specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). The upstream and downstream fragments of chlL gene were subcloned into pBluescript SK vector (Stratagene, USA) using KpnI, XhoI and SacI, BamHI sites, respectively. The rbcL promoter and psbA terminator were subsequently ligated into the resulting vector between the XhoI, HindIII and EcoRV, EcoRI sites, respectively. The codon optimized gfp gene was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and was ligated into the above vector with a HindIII restriction site at the 5′ end and an EcoRV site at the 3′ end of the coding region. All enzymes were commercially available from New England BioLabs (NEB, UK). The obtained vector was nominated as pMEMc1. The zeosin resistance (BLE) gene was amplified from vector pSP124 using primers BLE-F and BLE-R (Supplementary Table 1). The gfp gene of pMEMc1 was substituted by the BLE gene and generated vector pMEMc2.

Strains, transformation, and growth conditions

N. oceanica was inoculated into modified f/2 liquid medium, which was prepared as early description (Gan et al., 2017). The cells were grown in liquid cultures under continuous light (~50 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at 25°C. Transformation was conducted as description with minor modification (Wang et al., 2016; Xin et al., 2017). Vectors were linearized by restriction digestion, and purified and concentrated by ethanol precipitation. Microalgal cells at early log phase were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with sorbitol at 4°C. For each transformation reaction, 4 × 108 cells were mixed with 1 μg transforming cassette DNA. The mixture was added into a cuvette (Bio-Rad, 2 mm) and pulsed using GenePulse XcellTM (BioRad) apparatus with 12 kV cm−1 field strength, 50 μF capacitance, and 600 Ohm shunt resistance. The cells were immediately transferred into fresh f/2 medium and recovered under dim light for 48 h. For pMEMc1 transformants, GFP fluorescence was observed at indicated intervals while for pMEMc2 transformants, cells were plated on solid f/2 with 2.5 μg ml−1 zeosin (Solarbio, China) and colonies appeared after ~4 weeks.

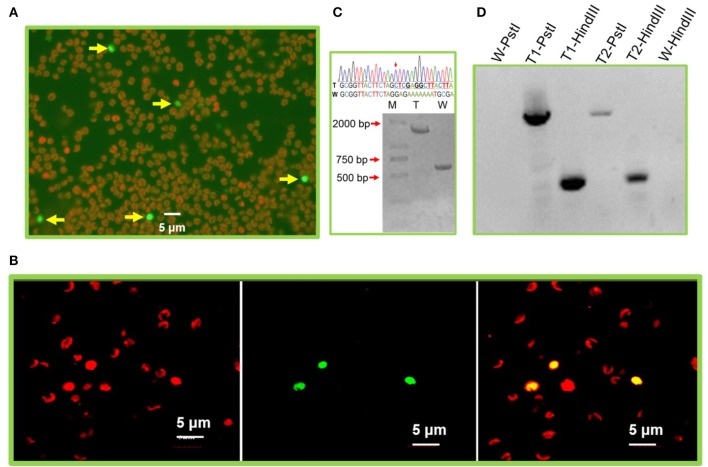

GFP expression detection of pMEMc1 transformants

An Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Japan), fitted with epifluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics, was used to visualize pMEMc1 transformants grown in liquid. Images were generated by either DIC or epifluorescence (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 520 nm) optics. An Olympus FluoViewTM FV1000 system was used to obtain laser confocal scanning microscope (LSCM) images of pMEMc1 transformants. Excitation at 488 and 559 nm were used for GFP and chlorophyll autofluorescence, respectively.

Genotyping of pMEMc2 transformants

Approximately 10 mL cultures of wild-type and pMEMc2-transformed cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,000 rpm, 3 min at 4°C). The cell pellet was washed twice, and then genomic DNA was extracted. Genomic PCR was used to confirm the homoplasmic integration of the vector into the plastid genome of transgenic lines. With the primers crossing chlL gene regions (c2-F and c2-R; Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1), 0.6 and 1.9 kb PCR products were expected to be detected for wild type and homoplasmic transformed cells (all copies of the chloroplast genome contained the ble gene), respectively. By contrast, for cells harboring heterogeneous chloroplast genomes, PCR amplification should generate both of the two bands (i.e., 0.6 and 1.9 kb DNA bands). All PCR fragments were purified (Cycle-Pure Kit, Omega, China) and sequenced (Sangon, China). Integration events were further analyzed by DNA gel blotting using non-radioactive DIG-containing ble gene probes (PCR DIG probe synthesis kit; Roche Diagnostics). The ble gene probes were labeled with DIG-dUTP using a pair of primer (BLE-F and BLE-R; Supplementary Table 1). Genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzyme HindIII or PstI, separated on 0.8% agarose gels, blotted, hybridized, and visualized.

Figure 1.

Construct map of homologous recombinant vector in N. oceanica chloroplast. PrbcL, promoter of large subunit of RuBisCO gene (rbcL); TpsbA, 3′ flanking sequence of gene encoding the D1 protein of Photosystem II (psbA); gfp, green florescence protein gene; chlL, light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase subunit; ble, zeosin resistance gene. Primers designed to examine the homoplasmic integration of the transforming cassette is indicated (c2-F and c2-R; Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Design and construction of destination vectors

To facilitate visualization of protein expression, the green florescence protein gene (gfp) was used as a reporter (Figure 1) and codon-optimized based on the featured codon bias and a high AT content (66.4%) of the N. oceanica chloroplast genome (Wei et al., 2013). The GFP gene was driven by an endogenous promoter (large subunit of RuBisCO, rbcL) and terminated by an endogenous terminator (3′ flanking sequence of gene encoding the D1 protein of Photosystem II, psbA) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Dataset 1). This expression cassette contains homology to the chlorophyll synthetic gene light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase subunit (chlL) region of the N. oceanica chloroplast genome. Transforming cassette will insert into the chlL locus by homologous recombination in expected transformants (Figure 1). Transformation construct harboring gfp gene (chlL-rbcL-gfp-psbA-chlL) were cloned into the plasmid pBluescript SK(-) and nominated as pMEMc1. The coding sequence of GFP in the vector was substituted with that of BLE gene and the resulting vector was designated as pMEMc2 (chlL-rbcL-ble-psbA-chlL; Figure 1 and Supplementary Dataset 2).

Introduction of reporter genes into the chloroplast genome

To probe the proper in vivo functioning of selected plastid promoters and terminators in N. oceanica, we started by transforming pMEMc1 cassette into N. oceanica wild-type strain by electroporation. Fluorescence microscopy of representative cells revealed that GFP protein was delivered into and expressed in N. oceanica (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 500–545 nm; Figure 2A and Supplementary Video 1). The number of transformants expressing GFP increased, and reached the highest levels 3 days after pulse. Laser confocal microscopy further confirmed the in vivo GFP expression in N. oceanica (Figure 2B). Despite of a low possibility of functioning in nuclear expression of these utilized plastid promoter and terminator, we cannot exclude the possibility that GFP expressed in nuclear instead of chloroplast.

Figure 2.

Exogenous gene expression in the N. oceanica chloroplast. (A) Microscopy images of GFP signals from representative microalgal cells transformed by pMEMc1. The fluorescent micrographs show the GFP expressing cells with green color (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 500–545 nm) and wild type cells with auto red fluorescence of chlorophyll (excitation: 559 nm, emission: 570–650 nm). (B) Laser confocal microscopic observation of N. oceanica pMEMc1 transformants. Left, chlorophyll fluorescence; middle, GFP fluorescence; right, merged image. (C) PCR amplification of wild-type cells and pMEMc2 transformants genomic DNA using c2-F and c2-R primers. PCR product of wild type cells generates a single 0.6 kb DNA band. Homoplasmic cells harbors a 1.3 kb transforming constructs (rbcL-ble-psbA) and was expected to generate a single 1.9 kb DNA band. (D) DNA gel blot of pMEMc2 transformants. Wild-type cells was used as a control. Genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzyme HindIII or PstI and blotted with DIG-dUTP labeled ble gene probes. W, Wild-type cells; T, pMEMc2 transformants; -PstI, genomic DNA digested PstI; -HindIII, genomic DNA digested HindIII.

Site-specific integration of transgenes into the chloroplast genomes

To validate the homologous recombination of the exogenous constructs into chloroplast genomes, pMEMc2 was transformed into the wild-type N. oceanica. Appropriately 4 × 108 N. oceanica cells were used for each pulse with 1 μg transforming cassette DNA. The cells were recovered under dim light for 48 h before being plated on f/2 plates containing zeocin (2.5 μg/ml). Approximately eight transformed colonies appeared on the selective plates which translated to a transformation frequency of about 2 × 10−8 μg−1 DNA. Two transformants were selected and analyzed for integration and homoplasmicity after multiple rounds of streaking of single colonies under zeocin-resistance selection (no less than four rounds each of which took approximately a month). Genomic PCR and sequencing confirmed that homoplasmic strains (all copies of the chloroplast genome contained the ble gene) were obtained and the rbcL-ble-psbA constructs (~1.3 kb) were integrated into all chloroplast genomes through homologous recombination of chlL regions (Figure 2C and Supplementary Dataset 3). Control reactions using genomic DNA from wild type as templates yield PCR products with a length of ~0.6 kb because they did not contain the vector sequences (Figure 2C and Supplementary Dataset 4). It is not clear whether a single insertion occurred in transformed cells (or whether random insertions happened in transformant genome). Further analysis of integration events was performed by DNA gel blot where a single band was observed by using ble probe in either HindIII or PstI digested genomic DNA of transformants (Figure 2D). Altogether, a stable and targeted transgene integration within the plastid genome was mediated by electroporation.

Discussion and conclusion

Chloroplast transformation was generally achieved by the biolistic process and ocassionally by PEG-mediated method (Maliga, 2004). However, neither of them is competent for most industrial microalgae. The major bottleneck is the inaccessibility of competent methods for DNA delivery into various microalgae with myriad cell size, complex, and largely unknown cell wall components. Thus, microalgae amenable to plastid transformation have been confined to limited species (Doron et al., 2016). Electroporation, which is normally used for nuclear transformation, was found to be capable of delivering exogenous DNA into plastid genome of N. oceanica (Supplementary Dataset 5) and C. reinhardtii (Zhang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to demonstrate the capacity of electroporation-mediated method in the development of transplastomic technology for species with small cell size and unknown cell-wall components. Using a plastid gene encoding chlorophyll biosynthetic enzyme CHLL as knock-in sites, the gfp gene was delivered into and expressed properly in N. oceanica by electroporation. Moreover, the antibiotic construct harboring the ble gene was utilized to validate the chloroplast integration of transformants. Genotyping of the homoplasmic cells showed a site-specific recombination of the transforming cassette into chloroplast genomes.

Restrictively, herein presented proof-of principle represents a starting point of plastome engineering for N. oceanica where the transformation frequency remains to be improved. To ensure the frequency, a standard practice should be developed and more recombination sites and more selectable marker genes should be tested. With a streamlined practice, electroporation should facilitate plastid engineering of relevant species with relative small cell sizes or unknown cell structure of which the chlroroplast manipultion is intractable by using microparticle bombardment or PEG-mediated transformation methods. Given that FA biosynthesis and photosynthesis processes predominantly take place in chloroplasts, transplastomic technology can be utilized to created engineered microalgal strains with optimized oil production and robust photosynthetic efficiency. Moreover, the incorporation of transgenes into the plastid genome for containment and high-level expression of recombinant proteins holds great promise for pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Author contributions

YL: Design the research; QG, JJ, and XH: Conducted the experiments; YL and SW: Wrote the first version of the manuscript; YL: Contributed to the final writing and presentation of the data.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge with apologies many excellent studies could not be cited due to space limitations. We are grateful to the reviewers for their valuable improvement to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (317010), Project of State Key Laboratory of Marine Resource Utilization in South China Sea (2018004 and 2016005), Foundation of Hainan University (KYQD1561), Project of Innovation & Development of Marine Economy (2017-285), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31401705, 31660744, and 41466002).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00439/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ajjawi I., Verruto J., Aqui M., Soriaga L. B., Coppersmith J., Kwok K., et al. (2017). Lipid production in Nannochloropsis gaditana is doubled by decreasing expression of a single transcriptional regulator. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 647–652. 10.1038/nbt.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock R. (2014). Genetic engineering of the chloroplast: novel tools and new applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 26, 7–13. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock R. (2015). Engineering plastid genomes: methods, tools, and applications in basic research and biotechnology. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 211–241. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton J., Gillham N., Harris E., Hosler J., Johnson A., Jones A., et al. (1988). Chloroplast transformation in Chlamydomonas with high velocity microprojectiles. Science 240, 1534–1538. 10.1126/science.2897716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corteggiani Carpinelli E., Telatin A., Vitulo N., Forcato C., D'angelo M., Schiavon R., et al. (2014). Chromosome scale genome assembly and transcriptome profiling of Nannochloropsis gaditana in nitrogen depletion. Mol. Plant 7, 323–335. 10.1093/mp/sst120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Qin S., Jiang P. (2014). Chloroplast transformation of Platymonas (Tetraselmis) subcordiformis with the bar gene as selectable marker. PLoS ONE 9:e98607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Zhao J., Wang Y., Qin S., Lu Y. (2018). Characterization and engineering of a dual-function diacylglycerol acyltransferase in the oleaginous marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11:32. 10.1186/s13068-018-1029-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doron L., Segal N., Shapira M. (2016). Transgene expression in microalgae-from tools to applications. Front. Plant Sci. 7:505. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Q., Zhou W., Wang S., Li X., Xie Z., Wang J., et al. (2017). A customized contamination controlling approach for culturing oleaginous Nannochloropsis oceanica. Algal Res. 27, 376–382. 10.1016/j.algal.2017.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge F., Huang W., Chen Z., Zhang C., Xiong Q., Bowler C., et al. (2014). Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase regulates triacylglycerol accumulation in the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Cell 26, 1681–1697. 10.1105/tpc.114.124982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel J. A., Specht E. A., Georgianna D. R., Mayfield S. P. (2013). Advances in microalgae engineering and synthetic biology applications for biofuel production. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 489–495. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golds T. J., Maliga P., Koop H. (1993). Stable plastid transformation in PEG-treated protoplasts of Nicotiana tabacum. Nat. Biotechnol. 11, 95–97. 10.1038/nbt0193-95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M., Hori K., Sasakisekimoto Y., Shimojima M., Ohta H. (2015). Manipulation of oil synthesis in Nannochloropsis strain NIES-2145 with a phosphorus starvation-inducible promoter from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Front. Microbiol. 6, 912–912. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang N. K., Jeon S., Kwon S., Koh H. G., Shin S., Lee B., et al. (2015). Effects of overexpression of a bHLH transcription factor on biomass and lipid production in Nannochloropsis salina. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8, 200–200. 10.1186/s13068-015-0386-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian O., Benemann C. S., Niyogi K. K., Vick B. (2011). High-efficiency homologous recombination in the oil-producing alga Nannochloropsis sp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 21265–21269. 10.1073/pnas.1105861108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot M., Raveh D., Sivan A., Arad S. M., Shapira M. (2002). Stable chloroplast transformation of the unicellular red alga Porphyridium species. Plant Physiol. 129, 7–12. 10.1104/pp.011023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D. (2003). Chloroplast research in the genomic age. Trends Genet. 19, 47–56. 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)00003-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Gao D., Hu H. (2014). High-efficiency nuclear transformation of the oleaginous marine Nannochloropsis species using PCR product. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 78, 812–817. 10.1080/09168451.2014.905184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang R., Patena W., Gang S. S., Blum S. R., Ivanova N., et al. (2016). An indexed, mapped mutant library enables reverse genetics studies of biological processes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 28, 367–387. 10.1105/tpc.15.00465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Chi X., Li Z., Yang Q., Li F., Liu S., et al. (2010). Isolation and characterization of a stress-dependent plastidial Δ12 fatty acid desaturase from the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris NJ-7. Lipids 45, 179–187. 10.1007/s11745-009-3381-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Chi X., Yang Q., Li Z., Liu S., Gan Q., et al. (2009). Molecular cloning and stress-dependent expression of a gene encoding Delta(12)-fatty acid desaturase in the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris NJ-7. Extremophiles 13, 875–884. 10.1007/s00792-009-0275-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Tarkowská D., Turecková V., Luo T., Xin Y., Li J., et al. (2014a). Antagonistic roles of abscisic acid and cytokinin during response to nitrogen depletion in oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica expand the evolutionary breadth of phytohormone function. Plant J. 80, 52–68. 10.1111/tpj.12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Xu J. (2015). Phytohormones in microalgae: a new opportunity for microalgal biotechnology. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 273–282. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Zhou W., Wei L., Li J., Jia J., Li F., et al. (2014b). Regulation of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway and its integration with fatty acid biosynthesis in the oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7:81. 10.1186/1754-6834-7-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliga P. (2004). Plastid transformation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 289–313. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliga P., Bock R. (2011). Plastid biotechnology: food, fuel, and medicine for the 21st Century. Plant Physiol. 155, 1501–1510. 10.1104/pp.110.170969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield S. P., Manuell A. L., Chen S., Wu J., Tran M., Siefker D., et al. (2007). Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplasts as protein factories. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18, 126–133. 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J. W., McGinty C. M., Quinn J. C. (2014). Global evaluation of biofuel potential from microalgae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 26, 7–13. 10.1073/pnas.1321652111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliner E., Pulman J. A., Zienkiewicz K., Childs K., Benning C., Farré E. M. (2017). A toolkit for Nannochloropsis oceanica CCMP1779 enables gene stacking and genetic engineering of the eicosapentaenoic acid pathway for enhanced long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid production. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 298–309. 10.1111/pbi.12772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radakovits R., Jinkerson R. E., Fuerstenberg S. I., Tae H., Settlage R. E., Boore J. L., et al. (2012). Draft genome sequence and genetic transformation of the oleaginous alga Nannochloropis gaditana. Nat. Commun. 3:686. 10.1038/ncomms1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasala B. A., Muto M., Lee P. A., Jager M., Cardoso R. M., Behnke C. A., et al. (2010). Production of therapeutic proteins in algae, analysis of expression of seven human proteins in the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Biotechnol. J. 8, 719–733. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00503.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. A., Davey M. P., Dennis J. S., Horst I., Howe C. J., Lea-Smith D. J., et al. (2010). Biodiesel from algae: challenges and prospects. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 21, 277–286. 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M., Van C., Barrera D. J., Pettersson P. L., Peinado C. D., Bui J., et al. (2013). Production of unique immunotoxin cancer therapeutics in algal chloroplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14–14. 10.1073/pnas.1214638110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieler A., Wu G., Tsai C.-H., Bullard B., Cornish A. J., Harvey C., et al. (2012). Genome, functional gene annotation, and nuclear transformation of the heterokont oleaginous alga Nannochloropsis oceanica CCMP1779. PLoS Genet. 8:e1003064. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Lu Y., Huang H., Xu J. (2012). Establishing oleaginous microalgae research models for consolidated bioprocessing of solar energy. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 128, 69–84. 10.1007/10_2011_122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Ning K., Li J., Hu Q., Xu J. (2014). Nannochloropsis genomes reveal evolution of microalgal oleaginous traits. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004094. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Lu Y., Xin Y., Wei L., Huang S., Xu J. (2016). Genome editing of model oleaginous microalgae Nannochloropsis spp. by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant J. 88, 1071–1081. 10.1111/tpj.13307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Shi Y., Ma X., Pan Y., Hu H., Li Y., et al. (2017). A type-I diacylglycerol acyltransferase modulates triacylglycerol biosynthesis and fatty acid composition in the oleaginous microalga, Nannochloropsis oceanica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:174. 10.1186/s13068-017-0858-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Xin Y., Wang D., Jing X., Zhou Q., Su X., et al. (2013). Nannochloropsis plastid and mitochondrial phylogenomes reveal organelle diversification mechanism and intragenus phylotyping strategy in microalgae. BMC Genomics 14:534. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Xin Y., Wang Q., Yang J., Hu H., Xu J. (2017). RNAi-based targeted gene knockdown in the model oleaginous microalgae Nannochloropsis oceanica. Plant J. 89, 1236–1250. 10.1111/tpj.13411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y., Lu Y., Lee Y.-Y., Wei L., Jia J., Wang Q., et al. (2017). Producing designer oils in industrial microalgae by rational modulation of co-evolving type-2 diacylglycerol acyltransferases. Mol. Plant 10, 1523–1539. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Hu H. (2014). High-efficiency nuclear transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by electroporation. Mar. Genomics 16, 63–66. 10.1016/j.margen.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Patena W., Armbruster U., Gang S. S., Blum S. R., Jonikas M. C. (2014). High-throughput genotyping of green algal mutants reveals random distribution of mutagenic insertion sites and endonucleolytic cleavage of transforming DNA. Plant Cell 26, 1398–1409. 10.1105/tpc.114.124099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz K., Zienkiewicz A., Poliner E., Du Z.-Y., Vollheyde K., Herrfurth C., et al. (2017). Nannochloropsis, a rich source of diacylglycerol acyltransferases for engineering of triacylglycerol content in different hosts. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:8. 10.1186/s13068-016-0686-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.