Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the physical and mental development of children after in vitro fertilization (IVF) and frozen embryo transfer (FET).

Methods: Between July 1995 and November 2003, 506 patients delivered 658 babies after IVF and ET treatment at our clinic (intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), 418; conventional IVF, (C‐IVF) 125; FET, 115). A survey of the physical and mental developmental of the children was conducted by mailing questionnaires to parents. Comparisons were made between three treatment procedures, and development of singleton, twin and triplet delivery.

Results: The response rate was 73.4% (483/658) for 324 children born after ICSI, 78 born after C‐IVF, and 81 born after FET. The height and weight of assisted reproductive technology (ART) children at birth were significantly lower than that of naturally conceived babies (ART children: natural delivery; 46.8 cm, 49.0 cm and 2524 g, 3040 g, respectively). However, there was no significant difference between the singletons alone and naturally conceived children irrespective of the ART method. In addition, mental development was the same between singletons and naturally conceived children. The ART group tended to delay body development such as ‘holding their head up’, ‘sitting up’, ‘crawl’ to moving growth in multiple births.

Conclusion: The physical and mental development of twins or triplets was significantly more delayed than that of naturally conceived babies, but had improved to a similar extent of the singletons after the age of 6 months. (Reprod Med Biol 2004; 3: 63–67)

Keywords: assisted reproductive technology, congenital aberration, malformation, physical and mental development

INTRODUCTION

TODAY MANY INFERTILE couples are able to benefit from assisted reproductive technology (ART). At present, approximately 1.0% of all babies in Japan are born as a result of conventional in vitro fertilization (C‐IVF) treatment and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Assisted reproductive technology was established for infertility treatment and in particular, ICSI has contributed to the treatment of severe male infertility. However, infertile women are frequently of advanced age at the time of conception and can have a variety of underlying causes of infertility. Furthermore, during the IVF process, the embryo is exposed to mechanical, thermal and chemical alterations. It is unclear whether these factors can increase chromosomal abnormalities, risk of congenital malformations, and so on. In addition, many studies have concluded that IVF pregnancies carry an increased risk for multiplicity, perinatal mortality, preterm birth and low birthweight in comparison with spontaneous pregnancies. 1 , 2 , 3 However, to date, published reports discussing such aspects is sparse and controversial. It is therefore very important to evaluate whether infants born as a result of ART experience increased rates of developmental complications when compared to those delivered after natural pregnancies.

In the present study, data from physical and mental examinations of ART children at their follow‐up visit at the age of certain years was compared with that from controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

THE STUDY INCLUDED 506 couples that underwent C‐IVF (n = 93) or ICSI (n = 316), frozen embryo transfer (FET) (n = 97). Conventional IVF resulted in 65 singletons, 24 sets of twins (n = 48) and four sets of triplets (n = 12) and ICSI resulted in 222 singletons, 86 twins (n = 172) and eight triplets (n = 24) after fresh embryo transfer. In addition, 80 singletons, 16 sets of twins (n = 32) and one set of triplets (n = 3) were delivered between July 1995 and November 2003 after FET. Twenty‐four of 506 couples underwent ART treatments twice; 15 of 24 patients delivered a singleton after both treatments, eight of 24 patients delivered a singleton on the first occasion, and twins on the second, whereas one delivered a singleton on the first occasion, and triplets on the second, and all resulted in physically and mentally healthy babies.

We sent written questionnaires to the parents of 658 children in order to assess development until the age of 3 months. Thereafter, 242, 220, 215, 204, 149, and 128 children were assessed at the age of 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year, 1.5 years and 2 years, respectively. Questionnaire responses were statistically analyzed. Examples of questionnaire content are shown in Table 1 (record of delivery) and Table 2 (growth at 1 year). Other questionnaires (physical and mental development) were administered at growth phases from 3 to 4 months, from 6 to 7 months, from 9 to 10 months, at 1.5 years, and at 2 years after delivery.

Table 1.

Medical record when babies delivered at clinic

| Congenital malformation | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| Duration of pregnant | ( ) weeks | ( ) days |

| Apgar score | ( ) | |

| Weight | ( ) g | |

| Height | ( ) cm | |

| Chest measurement | ( ) cm | |

| Head measurement | ( ) cm |

Table 2.

Mental and physical records of 1‐year‐old children

| Weight ( ) g | ||

| Height ( ) cm | ||

| 1. Weaning period completed | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 2. Walks with helping hand | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 3. Express self using gestures | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 4. Moves to music | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 5. Response to person's gesture | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 6. Shows happiness when receiving care | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

| 7. Eats three meals a day | Yes ( ) | No ( ) |

We examined physical growth and mental development in comparison with recommended standards of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare. In addition, we evaluated data concerning whether maternal or paternal causes of infertility might have influenced development.

RESULTS

WE RECEIVED COMPLETED questionnaires from the parents of 483 children (response rate: 483/658, 73.4%); 248 for children born by ICSI treatment, 78 for those born following C‐IVF and 81 for those born following FET. The male: female ratio was approximately 1:1 for the child population in the current study.

Similar to C‐IVF and FET, ICSI singleton children from fathers with low sperm quality had a similar developmental outcome to that of children from fathers with normal sperm parameters.

In singleton children, the mean (± SD) height and weight were as follows: ICSI, 48.5 ± 2.4 cm and 2905 ± 486 g; C‐IVF, 48.5 ± 3.8 cm and 2862 ± 632 g; FET, 48.5 ± 3.8 cm and 3063 ± 636 g; naturally conceived children 49.0 cm and 3040 g. In twins and triplet children, the corresponding values were: ICSI, 44.9 ± 3.8 cm and 2227 ± 459 g; 37.1 ± 3.2 cm and 1304 ± 281 g; C‐IVF 43.5 ± 4.6 cm and 2055 ± 519 g; 44.3 ± 2.0 cm and 1788 ± 282 g; FET, 44.5 ± 4.0 cm and 2196 ± 477 g; 44.3 ± 0.5 cm and 2077 ± 110 g (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physical growth of assisted reproductive technology children at delivery time

| Singleton | Twin | Triplet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICSI | C‐IVF | FET | ICSI | C‐IVF | FET | ICSI | C‐IVF | FET | |

| n (babies) | 217 | 64 | 74 | 165 | 44 | 28 | 24 | 12 | 3 |

| Weight (g) | 2905 ± 486 | 2834 ± 632 | 3023 ± 636 | 2227 ± 459 | 2055 ± 515 | 2196 ± 477 | 1304 ± 281 | 1788 ± 282 | 2077 ± 110 |

| Height (cm) | 48.5 ± 2.4 | 48.4 ± 3.8 | 48.5 ± 3.8 | 44.9 ± 3.8 | 43.5 ± 4.6 | 44.5 ± 4.0 | 37.1 ± 3.2 | 41.5 ± 2.0 | 44.3 ± 0.5 |

C‐IVF, conventional IVF; FET, frozen embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

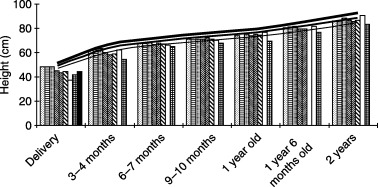

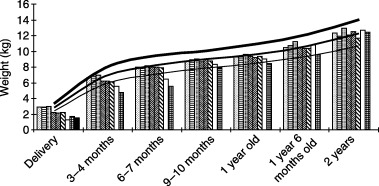

We obtained similar results for height and weight development for singletons, twins and triplets, and there was no significant difference in growth patterns between the ages of 3 months to 2 years for the ICSI and C‐IVF or FET children (1, 2).

Figure 1.

Growth curve of height at developmental stages in assisted reproductive technology children. , single ICSI; ▤, single C‐IVF;

, single FET;

, single FET;

, twin ICSI;

, twin ICSI;

, twin C‐IVF; ▧, twin FET; □, triplet ICSI; ▦, triplet C‐IVF; ▪, triplet FET;

, twin C‐IVF; ▧, twin FET; □, triplet ICSI; ▦, triplet C‐IVF; ▪, triplet FET;

10th percentile;

10th percentile;

50th percentile;

50th percentile;

90th percentile.

90th percentile.

Figure 2.

Growth curve of weight at developmental stages in assisted reproductive technology children., single ICSI; ▤, single C‐IVF;

, single FET;

, single FET;

, twin ICSI;

, twin ICSI;

, twin C‐IVF; ▧, twin FET; □, triplet ICSI; ▦, triplet C‐IVF; ▪, triplet FET;

, twin C‐IVF; ▧, twin FET; □, triplet ICSI; ▦, triplet C‐IVF; ▪, triplet FET;

10th percentile;

10th percentile;

50th percentile;

50th percentile;

90th percentile.

90th percentile.

The physical growth rate showed corresponding growth to 50th percentile curve from birth until 2 years of age in singletons. At birth, the weight ratio was low in singletons and high in multiple births (singleton 2.5%, twins 9.2%, and triplets 48.7%). Twins and triplets had a delay of 6 months more than singleton groups, however, twins was able to catch up the 50th percentile curve at approximately 6 months after birth. Moreover, triplets catch up to the 50th percentile curve at 1 year after birth (1, 2).

Table 4 showed the physical and mental development of ART children from 3 months to 2 years. Three groups (singleton, twin, triplet) in the ART group were compared. The ART group tended to delay body development such as ‘holding their head up’, ‘sitting up’, and ‘hangs on and can stand up’ to moving growth in multiple births. However, a significant difference was not discovered regarding movement, reaction, and understanding such as ‘extends hand to toy’, ‘reacts to television’, and ‘baby plays alone’ between three groups (singleton, twin, triplet). About each item, the significant differences were not found among the three groups after 1 year old.

Table 4.

Achievement rate of mental and physiological development at several growth stages

| Developmental stage | n | Developmental milestone | Singleton (%) | Twin (%) | Triplet (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–4 months | 238 | Hold their head up | 82.8 | 71.4 | 30.8 |

| (singleton, 134) | Laughed when played with | 96.3 | 95.6 | 75.0 | |

| (twin, 91) | Voice reaction | 91.7 | 94.5 | 58.3 | |

| (triplet, 13) | Can eat soup | 74.1 | 80.2 | 40.0 | |

| 6–7 months | 220 | Turns over in bed | 86.8 | 72.0 | 80.0 |

| (singleton, 130) | Sits up | 87.6 | 54.6 | 41.7 | |

| (twin, 75) | Extends hand to toy | 97.7 | 96.0 | 100.0 | |

| (triplet, 15) | Vocal expression | 99.2 | 97.3 | 100.0 | |

| Reacts to television | 98.5 | 98.7 | 100.0 | ||

| 9–10 months | 215 | Crawl | 84.8 | 72.0 | 66.7 |

| (singleton, 125) | Hangs on and can stand up | 88.0 | 66.7 | 42.9 | |

| (twin, 75) | Develop grip | 96.8 | 93.3 | 66.7 | |

| (triplet, 15) | It play alone | 96.8 | 97.3 | 80.0 | |

| It turns around when whispering | 100.0 | 100.0 | 80.0 | ||

| 1 year | 204 | Walks with support | 91.1 | 86.2 | 93.3 |

| (singleton, 124) | Mimics gestures | 92.7 | 89.2 | 100.0 | |

| (twin, 65) | Moves baby to music | 96.8 | 83.1 | 100.0 | |

| (triplet, 15) | Adult words are understood | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Pleased when meeting others | 94.3 | 95.4 | 100.0 | ||

| 1 year and 6 months | 149 | Child walks alone | 98.9 | 100.0 | 83.3 |

| (singleton, 89) | Child speaks | 97.7 | 100.0 | 83.3 | |

| (twin, 48) | Uses glass to drink | 93.3 | 87.5 | 77.8 | |

| (triplet, 12) | The nursing bottle is used | 23.6 | 47.9 | 75.0 | |

| Response to name | 97.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| 2 years | 128 | Can run | 98.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (singleton, 76) | Use a spoon | 98.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| (twin, 43) | Child scribbles with crayon | 100.0 | 93.0 | 100.0 | |

| (triplet, 9) | Mimic gestures | 100.0 | 97.7 | 100.0 | |

| Uses more than one word | 93.4 | 90.7 | 77.8 |

Congenital malformations were observed in 17 of the 354 children (4.8%). A complete list of all specific congenital malformations and chromosomal abnormalities is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Incidence of congenital malformation and chromosome abnormality at birth in assisted reproductive technology children

| Malformation mild atrial septal defect | 3 |

| Multiple fingers | 2 |

| Hydrocephalus | 1 |

| Esophageal atresia | 1 |

| Groin herniation | 3 |

| Jejunal stenosis | 1 |

| Palatal abscess | 1 |

| Intestinal stenosis | 1 |

| Hemangioma | 1 |

| Talipes equino varus | 1 |

| Chromosomal abnormality | |

| Trisomy 21 (Down's syndrome) | 1 |

| Trisomy 18 | 1 |

Incidence of malformation: 4.8% (17/354).

DISCUSSION

FEW REPORTS TO DATE have investigated in detail whether the postnatal development of children born following ART is comparable to that of naturally conceived children. There are especially few papers in Japan. 4 , 5 , 6

Compared to a natural conception, there is a slight increase in prevalence of congenital malformations in infants born after IVF, 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 but there is no significant increase in the prevalence of malformations. 8 , 9 , 10 Recently, in Katayama and Iida's study of the growth and development of IVF babies in their postnatal follow‐up study, IVF babies showed no remarkable disparity from naturally conceived babies, with the exception of developmental delay in the early infantile period due to multiple or premature deliveries. 4 Bonduelle et al. reported no indication that ICSI children have a lower psychomotor development than IVF children. 11 In addition, paternal risk factors associated with male‐factor infertility were found to play no role in developmental outcome, 10 , 12 which is supported by our findings in that there was no significant difference in developmental outcome despite different quality sperm used for IVF treatment. Moreover, Sutcliffe et al. concluded that children conceived after ICSI did not differ from their naturally conceived peers in physical health or development at ages up to 15 months. 8

Our findings are in agreement with the above‐mentioned studies. 8 , 9 , 10 Although the height of the twins and triplets was less than the 10th percentile before the age of 3 months, twins were able to catch up to the 50th percentile curve at approximately 6 months of age. Even triplets, who showed developmental delay of 6 months more than the singletons and twins, caught up to the 50th percentile curve at 6 months or 1 year of age. These findings, plus that of males and females showing a similar growth curve, indicate that ART babies without congenital malformation develop similar to naturally conceived babies (data no shown).

In terms of weight development, twins caught up to the 50th percentile curve at 6 months, while triplets caught up to the 50th percentile curve at between 6 months and 1 year of age. This finding strongly suggests that development is severely delayed only until 1 year of age regardless of the method of ART. Furthermore, babies born following ICSI or C‐IVF showed similar findings. While the development of triplets in the present study was most delayed, they went through the same developmental stages as the singletons and twins, except for the milestones of movement, reaction and the understanding such as ‘extends hand to toy’, ‘reacts to television’, and ‘plays alone’.

These findings suggest that ART treatment should avoid multiple pregnancies whenever possible. We had a comparatively high rate of multiple pregnancies because we included data from the establishment of our clinic, at which time we made every effort to achieve pregnancy. The incidence of congenital malformation among our ART children was not significantly higher than the normal incidence rate of 5–6%. However, one case of jejunal stenosis and one of intestinal stenosis did result from multiple pregnancies, and thus physicians should be cognizant of these risks of multiple pregnancies associated with ART treatment. Today's efforts to avoid multiple pregnancies should reduce these risks and make ART a safer treatment.

In the present study, the physical development of ART children was significantly more delayed than that of naturally conceived children. In ART children, while physical development was delayed until the age of 3–4 months, growth was not significantly different from that of naturally conceived babies after 6 months of age. Almost all singletons, irrespective of the ART procedure, showed similar physical and mental growth curves. Hypothetically then, if the number of embryos to be fertilized could be controlled freely, and singletons obtained, we could use different procedures without worrying about problems related to infant growth (ICSI, C‐IVF or FET). This in turn suggests that ART treatment especially singletons does not have a negative effect on the physical and mental development of children when compared with natural pregnancy and delivery as most children will reach average development rates by the age of 2. However, we recognize that our data was drawn from only a small number of babies born following ART treatment at a private clinic. Therefore, to further advance the safety and efficiency of ART treatment, it is necessary to extend the study of children conceived by ART to larger populations and to include such factors as investigation of antenatal development and a more thorough pediatric examination generally in early infancy or childhood.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kurinezuk JJ, Bower C. Birth defects in infants conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection: an alternative interpretation. BMJ 1997; 315: 1260–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koivurova S, Hartikainen AL, Gissler M, Hemmink E, Sovio U, Jarvelin MR. Neonatal outcome and congenital malformation in children born after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wennerholm U‐W, Bergh C, Hamberger L et al. Incidence of congenital malformations in children born after ICSI. Hum Reprod 2000; 15: 944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katayama E, Iida E, Suzuki S. (eds). Follow up of babies by IVF: Update . Tokyo: Medical View , 2001. (in Japanese).

- 5. Moriwaka O, Tanaka M, Watari M, Takashina T, Azumaguchi A, Kamiya H. Follow‐up study of 31 babies born after cryopreserved‐thawed embryo transfer. J Fertil Implant 1996; 13: 98–100 (in Japanese) . [Google Scholar]

- 6. Katayama E, Miyazaki A, Kitamura S et al. The growth and development of the in vitro fertilization babies from Ogikubo Hospital. J Fertil Implant 1999; 13: 50–55 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anthony S, Buitendijik SE, Dorrepaal CA, Lindner K, Braat DDM, Den Ouden AL. Congenital malformations in 4224 children conceived after IVF. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 2089–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sutcliffe AG, Saunders K, McLachlan R et al. A retrospective case‐control study of development and other outcomes in a cohort of Australian children conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection compared with a similar group in the United Kingdom. Fertil Steril 2003; 79: 512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonduelle M, Liebaers I, Deketelaere V et al. A neonatal data a cohort 2889 infants born after ICSI (1991–99) 2995 infants born after IVF (1983–1999). Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 671–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonduelle M, Ponjaert I, Van Steirteghem A, Devroey MP, Liebaers I. Development outcome at 2 years of age for children born after ICSI compared with children born after IVF. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonduelle M, Ponjaert I, Van Steirteghem A, Derde MP, Devroey P, Liebaers I. Developmental outcome at 2 years of age for children born after ICSI compared with children born after IVF. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koivurova S, Hartikainen AL, Gissler M, Hemminki E, Sovio U, Jarvelin MR. Neonatal outcome and congenital malformation in children born after in‐vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]