Abstract

Childhood cancer is a curable disease due to the development of chemo‐ and radiation therapies, but long‐term survivors suffer late side‐effects including infertility. Cytotoxic agents and radiation impair spermatogenesis and cause oligospermia or azoospermia as well as genetic damage in sperm. To date, the only established option to preserve fertility is cryopreservation of sperm before treatment and artificial reproduction techniques, if men with cancer can ejaculate, but only a quarter of men have banked sperm. Lack of information is the most common reason for failing to bank sperm. However, prepubertal patients who have only spermatogonia and spermatocytes in their testes do not benefit from cryopreservation of their sperm and assisted reproductive techniques. Thus, the only available option is to harvest testicular tissues before treatment for cryopreservation, from which immature germ cells can somehow be maturated. Autotransplantation of germ cells into the testis holds promise for fertility restoration, but contamination by malignant cells may induce relapse. Fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) with two surface markers could exclude contaminated leukemic cells from murine germ cells, and transplantation of sorted germ cells successfully restored fertility without transmission of leukemia. Human germ cells could be also isolated from human leukemia and lymphoma cell lines by FACS using surface markers. Before autotransplantation can be applied clinically, some issues, including the risk of contamination by malignant cells and in vitro propagation of spermatogonial stem cells, should be resolved.

Keywords: Infertility, Survivor, Chemotherapy, Radiation, Transplantation

Introduction

The incidence of childhood cancer is 141 per million annually in the USA. Among childhood cancer, leukemia accounts for 31%, brain tumor accounts for 14%, and malignant lymphoma accounts for 10%. Development of chemo‐ and radiation therapies has improved survival from childhood cancer. At present, more than 70% of patients with childhood cancer survive [1], and especially more than 90% of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia survive. The mortality of leukemia and lymphoma in Japanese children was also steeply decreasing [2], and the prevalence of cancer survivors among young adults is increasing [3]. Anticancer therapies can cause late side‐effects in long‐term survivors. For example, growth abnormalities occur in 51%, neurocognitive abnormalities occur in 30%, and infertility occurs in 30% of long‐term survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia [4]. Thirty percent of male survivors of childhood cancer suffer from azoospermia, and 18% of male survivors suffer from oligospermia [5]. The proportion of pregnancies of partners of male survivors that ended with a liveborn infant was significantly lower than for partners of male siblings of survivors who were the control group for comparison [6]. Survivors with azoospermia cannot father children even with assisted reproductive techniques. Infertility is a common late side‐effect and is a common source of stress in survivors. Fifty‐one percent of men wanted children in the future, including 77% of men who were childless at cancer diagnosis [7]. Survivors also fear that past cancer treatment could lead to their having a child with a birth defect or genetic abnormality [8]. In this review, we discuss the current strategy and future perspectives to preserve male fertility in children with malignant disease.

Testicular damage by chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Cytotoxic agents and radiation impair spermatogenesis and cause oligospermia or azoospermia. Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, chlorambucil, and busulfan, are gonadotoxic. The chance of recovery of spermatogenesis following cytotoxic insult, and also the extent and speed of recovery, are related to the agent used and the dose received [9]. After 6 cycles of MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisolone) or a comparable regimen, 90–100% of patients experience prolonged azoospermia. In sharp contrast, nonalkylating regimens such as ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) cause transient azoospermia in a third of patients, who usually make a full recovery [10, 11]. Cisplatin‐based chemotherapy for testicular cancer causes transient azoospermia or oligospermia, but sperm count will recover to normal in 50% at 2 years and 80% at 5 years [12].

Irradiation also impairs spermatogenesis, and spermatogonia are more radiosensitive than spermatocytes or spermatids [9]. Doses of irradiation >0.35 Gy cause azoospermia, which may be reversible. The time taken for recovery increases with larger doses; complete recovery takes place within 9–18 months following radiation with <1 Gy, but doses in excess of 2–6 Gy may result in permanent azoospermia [9, 13]. Irradiation with more than 20 Gy on testes impairs Leydig cell function [13, 14]. Scattered irradiations affect spermatogenesis at lower doses than single‐dose irradiation. Inverted Y‐inguinal field irradiation at more than 1.2 Gy in 14–26 fractions for Hodgkin disease causes permanent azoospermia [15]. Semen analysis following bone marrow transplantation conditioned with whole‐body irradiation and cyclophosphamide showed permanent azoospermia [16].

Fertility preservation for cancer patients

The only established option to preserve fertility for men who receive chemotherapy or radiotherapy is cryopreservation of sperm before treatment for use in artificial reproduction techniques (ART). Patients who can ejaculate semen before cancer treatment can benefit from sperm. With in vitro fertilization in combination with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF‐ICSI), only a few sperm are necessary for future fatherhood [17]. The clinical pregnancy rate by ICSI using cryopreserved sperm from men with malignant neoplasm was 42–56% per retrieval [18, 19]. Fifty‐one percent of men diagnosed with cancer wanted children in the future, including 77% of men who were childless at cancer diagnosis [7]. However, only 60% of men recalled being informed about infertility as a side‐effect of cancer treatment, and just 51% had been offered sperm banking. Those who discussed infertility with their physicians had greater knowledge about cancer‐related infertility and were significantly more likely to bank sperm. Only 24% of men banked sperm, including 37% of childless men. Lack of information was the most common reason for failing to bank sperm (25%). On the other hand, 91% of oncology physicians agreed that sperm banking should be offered to all men at risk of infertility as a result of cancer treatment, but 48% either never bring up the topic or mention it to less than a quarter of eligible men [20]. Barriers cited included lack of time for the discussion, perceived high cost, and lack of convenient facilities. Oncologists reported they would be less likely to offer sperm banking to men who had poor prognosis or who had aggressive tumors.

Even if survivors suffer azoospermia after cancer treatment, sperm retrieval leading to pregnancy is possible by TESE‐ICSI. Sperm retrieval was possible in 9 of 20 TESE (45%) for azoospermia after chemotherapy, resulting in clinical pregnancy in 3 of 9 couples (33%) and live deliveries in 2 of 9 couples (22%) [21]. In 5 among 12 patients (41.6%) with azoospermia after chemotherapy for testicular cancer or lymphoma, motile spermatozoa for ICSI were retrieved by TESE, and one pregnancy was obtained after 8 ICSI cycles in 5 couples, resulting in the delivery of a healthy girl [22]. However, chemotherapy or radiotherapy is capable of causing genetic damage in sperm [23, 24, 25, 26], and ICSI may circumvent the natural selection for damaged sperm.

Other strategies to preserve fertility are the protection of testis from cytotoxic agents. Testicular circulatory isolation in the form of brief clamping of the spermatic cord during drug administration preserved fertility in rat [27, 28]. It has been suggested that “spermatogenic arrest” caused by drug‐induced blockage of the pituitary–gonadal axis protects testis from the effect of chemotherapy [29], and hormonal protection of germ cells has been successful in rodents [30, 31]. However, hormonal protection of germ cells could not preserve fertility in men with lymphoma receiving chemotherapy [32].

Fertility preservation for prepubertal cancer patients

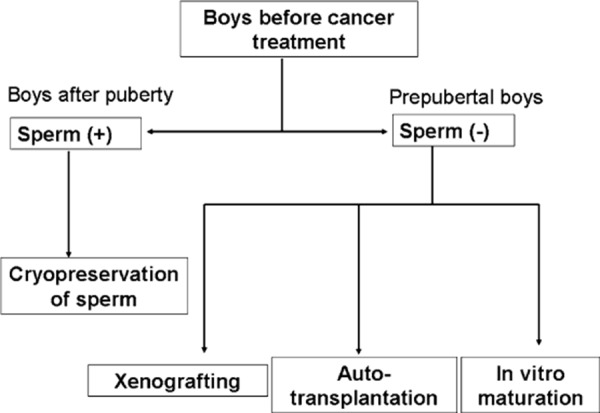

Whereas postpubertal males can cryopreserve their own sperm, to date, there are no options for preserving fertility in the prepubertal boy, who is likely to be azoospermic after chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Prepubertal boys have only spermatogonia and spermatocytes in their testes and do not benefit from cryopreservation of their sperm and ART. Thus, the only available option is to harvest testicular tissues for cryopreservation before treatment, from which immature germ cells can somehow be maturated (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Strategy to preserve fertility in boys with childhood cancer. Boys after puberty can ejaculate semen before treatment, which can be cryopreserved. Prepubertal boys who have no sperm in their testis do not benefit from cryopreservation of their sperm. The available option is to harvest testicular tissues, from which immature germ cells can somehow be maturated; in vitro maturation, xenografting, and autotransplantation

In vitro maturation of human germ cells to spermatid‐like cells has been successful, but the spermatid‐like cells did not develop normally [33]. Clinical application of in vitro maturation is currently technically difficult. Xenografting of testis tissues from pig or goat under the skin of immunodeficient mice has been reported to result in complete spermatogenesis [34]. Xenografting of adult human testis tissues to immunodeficient mice has been attempted, and spermatogonia were maintained for several months [35, 36]. Spermatogonia also survived for several months by means of xenografting of testicular tissues from prepubertal boys or cryptorchid testis to immunodeficient mice [37, 38, 39]. However, normal spermatogenesis was not found in xenografted tissues. Xenogeneic spermatogenesis also raises ethical issues and presents the risk of transmission of animal pathogens [40].

Another method to maturate immature germ cells is transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells into the testis [41]. A single‐cell suspension of germ cells is introduced into seminiferous tubules from rete testis or efferent ducts of recipient mouse testis with a fine glass needle. Recipient testis was treated with alkylating agents prior to transplantation, resulting in diminishing germ cells. Introduced germ cells are distributed throughout the seminiferous tubules, and a small number of spermatogonial stem cells reach the basement membrane and expand along the basal membrane [42]. One month after transplantation, colonized spermatogonial stem cells start spermatogenesis. Transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells into infertile mutant mice restored fertility and resulted in progeny with the genetic make‐up of the donor male [43]. Germ cell transplantation was also successful in other animals, including goats [44] and primates [45]. Spermatogenesis was recovered in X‐irradiated monkey testis after transplantation, and germ cell transplantation presents new possibilities for preservation of fertility potential in prepubertal cancer patients. Before cancer therapy, testicular tissues may be harvested and cryopreserved. After recovery from cancer, germ cells may be autotransplanted.

Cryopreservation of spermatogonial stem cells before transplantation is also possible. Donor testis cells isolated from prepubertal or adult mice and frozen from 4 to 156 days at −196°C were able to generate spermatogenesis in recipient seminiferous tubules [46]. Small pieces of mouse testicular tissues were successfully cryopreserved, thawed, and transplanted into mouse testes [47]. Furthermore, the extent of colony generation of freeze–thawed testis cells after transplantation into testes was 11 times that from fresh donor cells, because a large proportion of the stem cells survived the cryopreservation procedure based on their higher viability, while the remainder of the testicular cells underwent significant damage and died [48]. Autotransplantation would be advantageous in that spontaneous conception could occur. However, autotransplantation of germ cells from cancer patients poses the risk of transmission of malignant cells. Transplantation of testicular cells from leukemic rats induced transmission of leukemia [49]. Therefore, germ cells should be completely isolated from malignant cells.

Recently, many surface markers for spermatogonial stem cells have been identified by means of the germ cell transplantation technique. Selection of mouse testis cells with anti‐beta1‐ or anti‐alpha6‐integrin antibody produced cell populations with significantly enhanced ability to colonize recipient testes after transplantation [50]. Germ cells with high forward‐scattering (FSChigh) and low side‐scattering (SSClow) properties on fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) possess spermatogonial stem cell activity [51]. Selection of both mouse and rat testis cells with anti‐CD9 antibody resulted in 5‐ to 7‐fold enrichment of spermatogonial stem cells from intact testis cells [52]. Highly enriched spermatogonial stem cell activity was found in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I− Th‐1+ c‐kit− fraction, and this fraction was CD24+ αv‐integrin− Sca‐1− CD34− [53]. The combination of these surface markers which are specific for either spermatogonial stem cells or cancer cells would be utilized for exclusion of cancer cells from spermatogonial stem cells. Actually, FACS with antibodies against two surface markers, MHC class I and common leukocyte antigen (CD45), could exclude contaminated leukemic cells from murine germ cells [54]. Spermatogonial stem cells were isolated by setting gates for “MHC‐class I‐negative and CD45‐negative region” among the FSChigh, SSClow cell population. Isolated spermatogonial stem cells were also successfully transplanted as germ cells into recipient mouse testes treated with busulfan before, and spermatogenesis was recovered without transmission of leukemia.

However, there are some issues to be resolved before autotransplantation can be applied clinically. The first is that humans can develop many types of malignant disease and disease subtypes. The most common childhood cancer is leukemia, followed by central nervous system neoplasm and lymphoma. Leukemia and lymphoma account for approximately 30 and 10%, respectively, of cancers diagnosed in children less than 15 years of age. Human leukemia cell lines and lymphoma cell lines were also completely isolated by FACS with antibodies against MHC class I and CD45 from human germ cells. Chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells were not completely excluded from the germ cell fraction by the two surface markers because of the low expression of MHC class I on the surface of K562 cells. Other human leukemias also show decreased surface expression of MHC class I [55]. Treatment with interferon‐gamma (IFN‐γ) induced MHC class I expression on K562 cells and made it possible to exclude K562 cells from the germ cell fraction. IFN‐γ induces expression of MHC class I on the cell surface by upregulating proteasomes [56]. Approximately 10% of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias are CD45 negative [57]. Therefore, it is necessary to immunophenotype malignant cells of each patient before isolation and either to induce expression of surface markers or to add appropriate antibodies against specific surface markers of malignant cells that are not expressed on spermatogonial stem cells.

Isolation of spermatogonial stem cells from malignant cells still harbors the risk of contamination by malignant cells [58, 59, 60]. Contamination by some leukemic cells may occur after sorting, because of technical errors. Therefore, reliable, sensitive methods to detect contamination by minimal malignant cells should be developed before clinical application. Xenografting of testicular tissues from leukemic mice into nude mice resulted in development of leukemia in all donor mice, and may be used for detecting leukemic cell contamination [61], although only 5 of 20 xenografts with human leukemic cells (25%) developed tumors in donor immunodeficient mice [62].

Another issue is the feasibility of the transplantation technique. Attempts have been made to infuse human testis with dye via the rete testis [63]. Parents of boys surviving at least 2 years after diagnosis of cancer were asked about collecting germ cells for fertility preservation, and collection by means of biopsy was approved by 61%, hemicastration by 33%, and sperm collection by 70% [64]. Harvested testicular tissues may not contain enough spermatogonial stem cells to undergo spermatogenesis, and in vitro culture of human spermatogonial stem cells may be required to increase the rate of successful transplantation. In the presence of glial cell line‐derived neurotrophic factor, epidermal growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and leukemia inhibitory factor, gonocytes isolated from neonatal mouse testis proliferated over a 5‐month period [>10‐fold] [65]. Testicular cells from adult human were also cultured in vitro, and could be propagated up to 15 weeks [66]. The number of human spermatogonial stem cells increased 18459‐fold within 64 days. The normality of meiosis after cryopreserving and transplanting human spermatogonial stem cells should be also assessed [67].

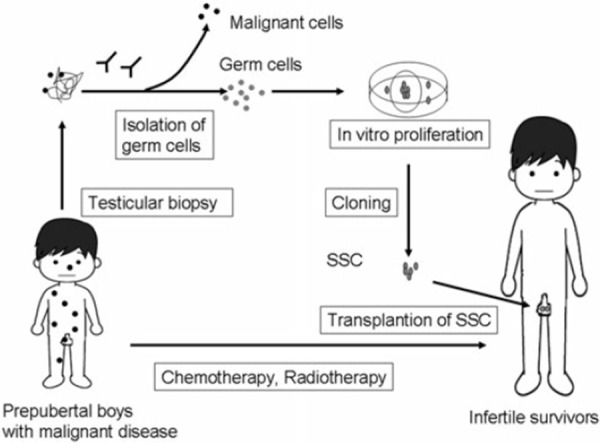

One future direction to circumvent these problems could be a combination of in vitro proliferation of human spermatogonial stem cells with exclusion of malignant cells before transplantation (Fig. 2): testicular tissues could be biopsied from prepubertal boys before chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and cryopreserved. If surviving patients become azoospermic, cryopreserved testicular tissues would be thawed, and spermatogonial stem cells would be isolated from malignant cells by FACS with several surface markers. After isolation, an isolated single stem cell could form a colony in culture, from which only 1 cell would be chosen for in vitro proliferation with no risk of tumor cell contamination [60]. Pure spermatogonial stem cells propagated in vitro would be transplanted into surviving infertile men.

Figure 2.

Combination of isolation and in vitro proliferation of human spermatogonial stem cells (SSC) to preserve fertility in prepubertal boys with malignant disease. Testicular tissues could be biopsied from prepubertal boys before chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and cryopreserved. SSC would be isolated from malignant cells by FACS with several surface markers, and isolated SSC proliferated in vitro. A single stem cell could form a colony in culture, from which only 1 cell would be chosen for further in vitro proliferation with no risk of tumor cell contamination. Pure SSC would be transplanted into surviving infertile men

Conclusions

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can impair spermatogenesis and cause infertility in long‐term survivors of childhood cancer. To date, the only established option to preserve fertility is cryopreservation of sperm before treatment for use in artificial reproduction techniques, if men with cancer can ejaculate. Prepubertal patients who have only spermatogonia and spermatocytes in their testes do not benefit from cryopreservation, and autotransplantation of isolated spermatogonial stem cells could be a potential option for fertility preservation in the near future, although some hurdles must be overcome before clinical application.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Ohta, Tetsuya Takao, Yasuhiro Matsuoka, Yasushi Miyagawa, Shingo Takada, Kiyomi Matsumiya, Teruhiko Wakayama, and Akihiko Okuyama for their collaboration in our research.

References

- 1. Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer, 2004, 101, 3–27 10.1002/cncr.20288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoshimi I, Sobue T. Cancer statistics digest. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2004, 34, 360–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bleyer WA. The impact of childhood cancer on the United States and the world. CA Cancer J Clin, 1990, 40, 355–367 10.3322/canjclin.40.6.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leung W, Hudson MM, Strickland DK, Phipps S, Srivastava DK, Ribeiro RC et al. Late effects of treatment in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol, 2000, 18, 3273–3279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomson AB, Campbell AJ, Irvine DC, Anderson RA, Kelnar CJ, Wallace WH. Semen quality and spermatozoal DNA integrity in survivors of childhood cancer: a case–control study. Lancet, 2002, 360, 361–367 10.1016/S0140‐6736(02)09606‐X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Green DM, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Mertens AC, Donaldson SS, Ruymann FB et al. Pregnancy outcome of partners of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol, 2003, 21, 716–721 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schover LR, Brey K, Lichtin A, Lipshultz LI, Jeha S. Knowledge and experience regarding cancer, infertility, and sperm banking in younger male survivors. J Clin Oncol, 2002, 20, 1880–1889 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schover LR. Motivation for parenthood after cancer: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;2–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Howell SJ, Shalet SM. Spermatogenesis after cancer treatment: damage and recovery. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;12–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.van der Kaaij MA, van Echten‐Arends J, Simons AH, Kluin‐Nelemans HC. Fertility preservation after chemotherapy for hodgkin lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2010 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. Sieniawski M, Reineke T, Josting A, Nogova L, Behringer K, Halbsguth T et al. Assessment of male fertility in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma treated in the german Hodgkin study group (GHSG) clinical trials. Ann Oncol, 2008, 19, 1795–1801 10.1093/annonc/mdn376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lampe H, Horwich A, Norman A, Nicholls J, Dearnaley DP. Fertility after chemotherapy for testicular germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol, 1997, 15, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shalet SM. Effect of irradiation treatment on gonadal function in men treated for germ cell cancer. Eur Urol, 1993, 23, 148–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bang AK, Petersen JH, Petersen PM, Andersson AM, Daugaard G, Jorgensen N. Testosterone production is better preserved after 16 than 20 gray irradiation treatment against testicular carcinoma in situ cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2009, 75, 672–676 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centola GM, Keller JW, Henzler M, Rubin P. Effect of low‐dose testicular irradiation on sperm count and fertility in patients with testicular seminoma. J Androl, 1994, 15, 608–613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anserini P, Chiodi S, Spinelli S, Costa M, Conte N, Copello F et al. Semen analysis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Additional data for evidence‐based counselling. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2002, 30, 447–451 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devroey P, Liu J, Nagy Z, Goossens A, Tournaye H, Camus M et al. Pregnancies after testicular sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non‐obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod, 1995, 10, 1457–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Revel A, Haimov‐Kochman R, Porat A, Lewin A, Simon A, Laufer N et al. In vitro fertilization‐intracytoplasmic sperm injection success rates with cryopreserved sperm from patients with malignant disease. Fertil Steril, 2005, 84, 118–122 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hourvitz A, Goldschlag DE, Davis OK, Gosden LV, Palermo GD, Rosenwaks Z. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) using cryopreserved sperm from men with malignant neoplasm yields high pregnancy rates. Fertil Steril, 2008, 90, 557–563 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schover LR, Brey K, Lichtin A, Lipshultz LI, Jeha S. Oncologists’ attitudes and practices regarding banking sperm before cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol, 2002, 20, 1890–1897 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan PT, Palermo GD, Veeck LL, Rosenwaks Z, Schlegel PN. Testicular sperm extraction combined with intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the treatment of men with persistent azoospermia postchemotherapy. Cancer, 2001, 92, 1632–1637 10.1002/1097‐0142(20010915)92:6<1632::AID‐CNCR1489>3.0.CO;2‐I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meseguer M, Garrido N, Remohi J, Pellicer A, Simon C, Martinez‐Jabaloyas JM et al. Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and ICSI in patients with permanent azoospermia after chemotherapy. Hum Reprod, 2003, 18, 1281–1285 10.1093/humrep/deg260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meistrich ML. Potential genetic risks of using semen collected during chemotherapy. Hum Reprod, 1993, 8, 8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robbins WA, Meistrich ML, Moore D, Hagemeister FB, Weier HU, Cassel MJ et al. Chemotherapy induces transient sex chromosomal and autosomal aneuploidy in human sperm. Nat Genet, 1997, 16, 74–78 10.1038/ng0597‐74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brandriff BF, Meistrich ML, Gordon LA, Carrano AV, Liang JC. Chromosomal damage in sperm of patients surviving Hodgkin's disease following MOPP (nitrogen mustard, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) therapy with and without radiotherapy. Hum Genet, 1994, 93, 295–299 10.1007/BF00212026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mas P, Daudin M, Vincent MC, Bourrouillou G, Calvas P, Mieusset R et al. Increased aneuploidy in spermatozoa from testicular tumour patients after chemotherapy with cisplatin, etoposide and bleomycin. Hum Reprod, 2001, 16, 1204–1208 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farr SA, Johnson FE, Taylor GT. Sociosexual behaviour and paternity in procarbazine‐exposed rats with or without regional testicular circulatory isolation. J Reprod Fertil, 1997, 110, 29–34 10.1530/jrf.0.1100029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson FE, Liebscher GJ, LaRegina MC, Tolman KC. Preservation of fertility following doxorubicin administration in the rat. Surg Oncol, 1992, 1, 145–150 10.1016/0960‐7404(92)90027‐I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gould SF, Powell D, Nett T, Glode LM. A rat model for chemotherapy‐induced male infertility. Arch Androl, 1983, 11, 141–150 10.3109/01485018308987473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weissenberg R, Lahav M, Raanani P, Singer R, Regev A, Sagiv M et al. Clomiphene citrate reduces procarbazine‐induced sterility in a rat model. Br J Cancer, 1995, 71, 48–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ward JA, Robinson J, Furr BJ, Shalet SM, Morris ID. Protection of spermatogenesis in rats from the cytotoxic procarbazine by the depot formulation of zoladex, a gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist. Cancer Res, 1990, 50, 568–574 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson DH, Linde R, Hainsworth JD, Vale W, Rivier J, Stein R et al. Effect of a luteinizing hormone releasing hormone agonist given during combination chemotherapy on post therapy fertility in male patients with lymphoma: preliminary observations. Blood, 1985, 65, 832–836 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee DR, Kim KS, Yang YH, Oh HS, Lee SH, Chung TG et al. Isolation of male germ stem cell‐like cells from testicular tissue of non‐obstructive azoospermic patients and differentiation into haploid male germ cells in vitro. Hum Reprod, 2006, 21, 471–476 10.1093/humrep/dei319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Honaramooz A, Snedaker A, Boiani M, Scholer H, Dobrinski I, Schlatt S. Sperm from neonatal mammalian testes grafted in mice. Nature, 2002, 418, 778–781 10.1038/nature00918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlatt S, Honaramooz A, Ehmcke J, Goebell PJ, Rubben H, Dhir R et al. Limited survival of adult human testicular tissue as ectopic xenograft. Hum Reprod, 2006, 21, 384–389 10.1093/humrep/dei352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Geens M, Block G, Goossens E, Frederickx V, Steirteghem A, Tournaye H. Spermatogonial survival after grafting human testicular tissue to immunodeficient mice. Hum Reprod, 2006, 21, 390–396 10.1093/humrep/dei412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goossens E, Geens M, Block G, Tournaye H. Spermatogonial survival in long‐term human prepubertal xenografts. Fertil Steril, 2008, 90, 2019–2022 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wyns C, Curaba M, Martinez‐Madrid B, Langendonckt A, Francois‐Xavier W, Donnez J. Spermatogonial survival after cryopreservation and short‐term orthotopic immature human cryptorchid testicular tissue grafting to immunodeficient mice. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 1603–1611 10.1093/humrep/dem062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wyns C, Langendonckt A, Wese FX, Donnez J, Curaba M. Long‐term spermatogonial survival in cryopreserved and xenografted immature human testicular tissue. Hum Reprod, 2008, 23, 2402–2414 10.1093/humrep/den272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson CA. Porcine endogenous retroviruses and xenotransplantation. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2008, 65, 3399–3412 10.1007/s00018‐008‐8498‐z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ‐cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1994, 91, 11298–11302 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogawa T. Spermatogonial transplantation: the principle and possible applications. J Mol Med, 2001, 79, 368–374 10.1007/s001090100228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Transplantation of male germ line stem cells restores fertility in infertile mice. Nat Med, 2000, 6, 29–34 10.1038/71496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Honaramooz A, Behboodi E, Blash S, Megee SO, Dobrinski I. Germ cell transplantation in goats. Mol Reprod Dev, 2003, 64, 422–428 10.1002/mrd.10205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schlatt S, Foppiani L, Rolf C, Weinbauer GF, Nieschlag E. Germ cell transplantation into X‐irradiated monkey testes. Hum Reprod, 2002, 17, 55–62 10.1093/humrep/17.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Avarbock MR, Brinster CJ, Brinster RL. Reconstitution of spermatogenesis from frozen spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Med, 1996, 2, 693–696 10.1038/nm0696‐693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shinohara T, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Kanatsu‐Shinohara M, Miki H, Nakata K et al. Birth of offspring following transplantation of cryopreserved immature testicular pieces and in vitro microinsemination. Hum Reprod, 2002, 17, 3039–3045 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kanatsu‐Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Restoration of fertility in infertile mice by transplantation of cryopreserved male germline stem cells. Hum Reprod, 2003, 18, 2660–2667 10.1093/humrep/deg483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jahnukainen K, Hou M, Petersen C, Setchell B, Soder O. Intratesticular transplantation of testicular cells from leukemic rats causes transmission of leukemia. Cancer Res, 2001, 61, 706–710 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Beta1‐ and alpha6‐integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1999, 96, 5504–5509 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shinohara T, Orwig KE, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cell enrichment by multiparameter selection of mouse testis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2000, 97, 8346–8351 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kanatsu‐Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. CD9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod, 2004, 70, 70–75 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cells share some, but not all, phenotypic and functional characteristics with other stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2003, 100, 6487–6492 10.1073/pnas.0631767100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fujita K, Ohta H, Tsujimura A, Takao T, Miyagawa Y, Takada S et al. Transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells isolated from leukemic mice restores fertility without inducing leukemia. J Clin Invest, 2005, 115, 1855–1861 10.1172/JCI24189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Majumder D, Bandyopadhyay D, Chandra S, Mukhopadhayay A, Mukherjee N, Bandyopadhyay SK et al. Analysis of HLA class IA transcripts in human leukaemias. Immunogenetics, 2005, 57, 579–589 10.1007/s00251‐005‐0018‐9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Strehl B, Seifert U, Kruger E, Heink S, Kuckelkorn U, Kloetzel PM. Interferon‐gamma, the functional plasticity of the ubiquitin‐proteasome system, and MHC class I antigen processing. Immunol Rev, 2005, 207, 19–30 10.1111/j.0105‐2896.2005.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ratei R, Sperling C, Karawajew L, Schott G, Schrappe M, Harbott J et al. Immunophenotype and clinical characteristics of CD45‐negative and CD45‐positive childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol, 1998, 77, 107–114 10.1007/s002770050424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hou M, Andersson M, Zheng C, Sundblad A, Soder O, Jahnukainen K. Decontamination of leukemic cells and enrichment of germ cells from testicular samples from rats with Roser's T‐cell leukemia by flow cytometric sorting. Reproduction, 2007, 134, 767–779 10.1530/REP‐07‐0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Geens M, Velde H, Block G, Goossens E, Steirteghem A, Tournaye H. The efficiency of magnetic‐activated cell sorting and fluorescence‐activated cell sorting in the decontamination of testicular cell suspensions in cancer patients. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 733–742 10.1093/humrep/del418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fujita K, Tsujimura A, Okuyama A. Isolation of germ cells from leukemic cells. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 2796–2797 10.1093/humrep/dem212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hou M, Andersson M, Eksborg S, Soder O, Jahnukainen K. Xenotransplantation of testicular tissue into nude mice can be used for detecting leukemic cell contamination. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 1899–1906 10.1093/humrep/dem085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fujita K, Tsujimura A, Hirai T, Ohta H, Matsuoka Y, Miyagawa Y et al. Effect of human leukemia cells in testicular tissues grafted into immunodeficient mice. Int J Urol, 2008, 15, 733–738 10.1111/j.1442‐2042.2008.02087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Brook PF, Radford JA, Shalet SM, Joyce AD, Gosden RG. Isolation of germ cells from human testicular tissue for low temperature storage and autotransplantation. Fertil Steril, 2001, 75, 269–274 10.1016/S0015‐0282(00)01721‐0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Berg H, Repping S, Veen F. Parental desire and acceptability of spermatogonial stem cell cryopreservation in boys with cancer. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 594–597 10.1093/humrep/del375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kanatsu‐Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S et al. Long‐term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69, 612–616 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sadri‐Ardekani H, Mizrak SC, Daalen SK, Korver CM, Roepers‐Gajadien HL, Koruji M et al. Propagation of human spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. JAMA, 2009, 302, 2127–2134 10.1001/jama.2009.1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tournaye H, Goossens E, Verheyen G, Frederickx V, Block G, Devroey P et al. Preserving the reproductive potential of men and boys with cancer: current concepts and future prospects. Hum Reprod Update, 2004, 10, 525–532 10.1093/humupd/dmh038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]