Abstract

To achieve a successful pregnancy in humans, sperm is required for capacitation, followed by binding to and entry into an oocyte. Maternal endometrial epithelial cells (EECs) prepare the appropriate implantation environment through regulation of immune cells and endometrial cells. After acquiring endometrial receptivity, a successful pregnancy consists of complex and finely regulated steps involving apposition, adhesion, invasion, and penetration. Glycodelin is a secretory glycoprotein that affects cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and motility. Glycodelin has four glycoforms (glycodelin‐A, ‐S, ‐F. and ‐C); differences in glycosylation affect each characteristic function. Glycodelin has a unique temporospatial pattern of expression, primarily in the reproductive tract where glycodelin is mid‐secretory phase‐dominant. Recent studies have demonstrated that glycodelin protein has the potential to regulate various processes, including immunosuppression, fertilization, and implantation. This review details the orchestrated regulation of successful pregnancy by glycodelin as well as a discussion of the basic characteristics of glycodelin.

Keywords: Endometrial epithelial cell, Fertilization, Glycodelin, Implantation, Sperm

Basic characteristics of glycodelin

After the initial identification of glycodelin in amniotic fluid [1], glycodelin was given various names by several investigators, such as placental α2‐globulin [1], chorionic α2‐microglobulin, α‐uterine protein, placental protein (PP14), progestogen‐dependent endometrial protein (PEP), pregnancy‐associated endometrial α2‐globulin (α2‐PEG), and progesterone‐associated endometrial protein (PAEP) [2]. Currently, the Human Genome Organization uses PAEP and glycodelin as the official symbol and preferred term amongst the list of recommended names, respectively.

The glycodelin gene is located at 9q34.3 and the mRNA is comprised of 7 exons. Several splicing variants of glycodelin mRNA have been reported in the female and male reproductive organs and an endometrial cell line [3, 4, 5]; however, the differentiation of physiologic functions is still unknown. Although the full length of glycodelin mRNA encodes 180 amino acids and the predicted molecular mass of glycodelin protein is about 18–19 kDa, on SDS‐PAGE and Western blotting, the glycodelin band is located at 50–60 kDa, because of glycosylation modification and homodimeric action.

Temporospatial expression of glycodelin

Glycodelin has a limited spatial pattern of expression. Glycodelin expression in mammary glands [6] and endometrium is well described, and this secretory protein is regulated by progesterone. In addition to secretory and decidualized endometrium [7, 8], glycodelin is expressed in bone marrow [9, 10], ovaries [11], fallopian tubes [12], and seminal vesicles [13, 14]. The unique distribution of glycodelin suggests the relationship between glycodelin function and immunologic and hormonal regulation of reproduction.

Based on differentiation of the attached glycosylation modification pattern, glycodelin can be divided into four glycoforms (glycodelin‐A, ‐S, ‐F, and, ‐C). The postfix represents the field to act for each glycoform. In the male reproductive tract, glycodelin‐S is secreted from seminal vesicles to the seminal fluid [4, 13, 14]. In the female genital tract, glycodelin‐A is mainly expressed in EECs [15, 16] and secreted into the uterine fluid [17] and amniotic fluid [7, 18]. Granulosa cells secrete glycodelin‐F into the follicular fluid and glycodelin‐C is detected in cumulus cells [19].

Progesterone‐induced glycodelin‐A also has a characteristic temporal pattern of expression. During the proliferative phase, glycodelin has not been immunohistochemically detected in the endometrium; however, 4–5 days after ovulation glycodelin expression can be gradually detected, with a peak 10 days after ovulation [20]. During human pregnancy glycodelin is expressed in decidualized EECs or amniotic fluid, peaking at 10–18 weeks of gestation [7, 21]. Glycodelin in EECs is secreted to the uterine cavity. Glycodelin can only be detected in uterine flush during the mid‐secretory phase [22]. Moreover, glycodelin can be measured in serum. The concentration of serum glycodelin is quite low compared to the concentration of glycodelin in the endometrium or a uterine flush, but can be detected throughout the menstrual cycle. After ovulation, the serum glycodelin level gradually increases, with a peak in the menstrual phase [15]. These characteristic temporal patterns of expression are in response to the secretion of progesterone. During anovulatory cycles, increasing glycodelin expression can not be measured [23]. Glycodelin expression is increased by the administration of micronized progesterone for anovulatory cycles in women [24]; however, glycodelin levels in women with premature ovarian insufficiency undergoing oocyte donation and embryo transfer are much lower compared to women with normal menstrual cycles [25]. Together, this evidence indicates that the expression of glycodelin is regulated not only by progesterone, but also by another complex system, involving hCG [26] and relaxin [27].

In addition to hormonal regulation, the expression of glycodelin is regulated by one of the histone modifications, histone acetylation. The balance of two enzymes, histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase, regulates a part of gene transcription. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs), such as trichostatin A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), increase histone acetylation and induce expression of glycodelin mRNA and protein [28]. Unique glycodelin temporospatial expression is based on hormonal and epigenetic regulation.

Glycodelin in the immune response

Pregnancy is a type of semi‐allograft implantation; therefore, suppression of maternal immune response is important to protect the combination of embryo and endometrial tissue for establishment of human pregnancy.

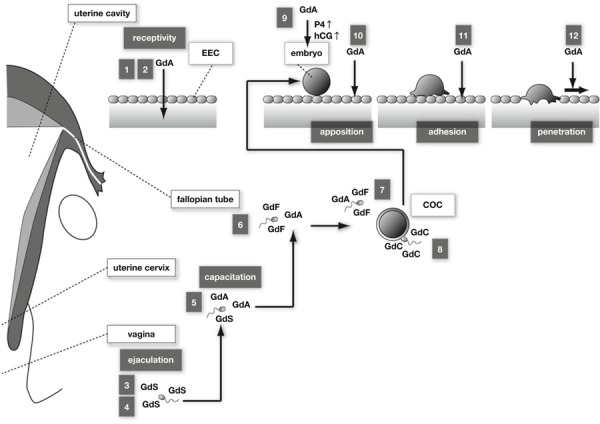

Okamoto et al. [29] demonstrated that glycodelin‐A suppresses the cytotoxicity of natural killer cells in the first study to point out the relationship between glycodelin and immune cells. Subsequently, numerous studies have clarified the role of glycodelin in regulating the immune system during pregnancy (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Glycodelin in successful pregnancy. 1 Glycodelin‐A (GdA) suppresses the cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. 2 Th2‐dominant Th1/Th2 balance is induced by GdA‐mediated apoptosis of Th1 cells, and increased secretion of Th2 cytokines. 3 Sperm morphology dependent glycodelin‐S (GdS) binding to sperm. 4 GdS prevents capacitation by inhibiting albumin‐induced cholesterol efflux. 5 Capacitation of sperm by replacement of GdS to GdA in the uterine cervix. 6 GdF (and GdA) binds to sperm and inhibits the progesterone‐induced acrosome reaction. 7 GdA suppresses the binding between sperm and oocyte. 8 Replacement of GdF/GdA to Glycodelin‐C (GdC) derived from cumulus oocyte complex (COC) induces acrosome reaction. 9 GdA induces secretion of progesterone and hCG from trophoblast. 10 GdA transdifferentiates EECs. 11 Adhesion ability of EECs against embryo is up‐regulated by GdA. 12 Increased expression of GdA accelerates motility of EECs and thereby assists embryo penetration

Glycodelin‐A stimulates human choriogonadotropin (hCG) production by trophoblast and induces progesterone secretion from trophoblast [30, 31]; hCG treatment increases Fas ligand (FasL) expression in endometrial epithelial and stromal cells [32]. Treatment with glycodelin‐A induces apoptosis of Th1 cells more than Th2 cells [33], probably due to the expression of Fas receptors in Th1 cells more abundantly than Th2 cells [33, 34]. The glycodelin‐A‐induced cell apoptosis has been mediated by activation of caspase‐3, ‐8, and ‐9 [33].

Natural killer cells occupy 70 % of the leukocyte population within the uterus. Lee et al. [35] demonstrated that glycodelin‐A induces the secretion of Th2 cytokines, such as interleukin‐6 and ‐13, and GM‐CSF from natural killer cells. IL‐6 and GM‐CSF acts on blastocysts through stimulation of trophoblast cell motility and differentiation. These observations indicate that glycodelin‐A indirectly engages the regulation of Th2‐dominant Th1/Th2 balance for successful pregnancy.

Glycodelin in sperm reaction

After ejaculation into the vagina, glycodelin‐S quickly binds to spermatozoa, depending on the morphology of the sperm [36]. Teratospermia has a low fertilization ratio, which likely accounts for poor accessibility of glycodelin‐S to spermatozoa. Glycodelin‐S inhibits albumin‐induced cholesterol efflux from spermatozoa [37], and thereby prevents capacitation, which is triggered by cholesterol decrement in the sperm plasma membrane. During the peri‐ovulation phase, glycodelin‐A is not abundant in the uterine mucus and, therefore, glycodelin‐S in the seminal plasma has easy access to spermatozoa without binding competition to glycodelin‐A. Albumin is less in seminal plasma and abundant in the uterine mucus. Prevention of capacitation against moving spermatozoa in the uterine cavity by a concentration gradient of albumin is meaningful because fertilization is allowed a few hours after capacitation [38]. After removal of glycodelin‐S, cholesterol efflux and capacitation occur in sperm.

In the fallopian tube, glycodelin‐A and glycodelin‐F are expressed. Glycodelin‐F, which binds to sperm, inhibits the progesterone‐induced acrosome reaction [39]. Elevated progesterone after ovulation induces the acrosome reaction and likely prevents multiple fertilization because acrosome‐reacted sperm lose the ability to bind to the zona pellucida [40]. Binding of glycodelin‐F to capacitated sperm is important to maintain the acrosome‐unreacted state until apposition of the sperm and oocyte. Glycodelin‐A attached to sperm supports the zona pellucida‐induced acrosome reaction. Because of this glycodelin‐A function, sperm can start the acrosome reaction effectively and immediately after binding to zona pellucida. Glycodelin‐F and glycodelin‐A attached to sperm are replaced by glycodelin‐C in cumulus cells. Oehlinger et al. [41] demonstrated that glycodelin‐A suppresses the binding between sperm and oocyte and it is believed as the multiple pregnancy system; however, the balance between the blockade of sperm–oocyte binding by glycodelin‐A and glycodelin‐F, and the replacement of functional glycodelin‐A and glycodelin‐F by glycodelin‐C effectively regulate the successful singleton pregnancy.

Glycodelin in implantation

Endometrial receptivity peaks in the mid‐secretory phase called the ‘implantation window’. Glycodelin is induced by progesterone, which is abundantly secreted after ovulation, and increases hCG secretion from blastocyst [30, 31]; thereafter, the secreted hCG induces glycodelin secretion from EECs [26]. Through this cyclic mechanism, glycodelin expression is accelerated during the mid‐secretory phase. In association with glycodelin [15, 16], the expression of endometrial receptivity marker proteins have been changed through the implantation window, such as leukemia inhibitory factor [28, 42], integrin αvβ3 [43], trophinin [44], and MUC‐1 [45] in EECs. MUC‐1 is the cell surface mucin and is thought to act as an anti‐adhesion molecule by covering binding sites of adhesion molecules. Both the increased expression of trophinin, which is a homodimeric adhesion molecule, and the decreased expression of MUC‐1 regulate adhesion between the embryo and EECs.

In contrast, glycodelin affects EEC adhesion against embryos [5]. Transfection of glycodelin cDNA lacking a putative N‐terminal signal peptide into an EEC line (Ishikawa cells) resulted in increased adhesion ability between EECs and embryo models. In culturing Ishikawa cells, glycodelin secretion to culture media is undetectable [46]. These results indicate that glycodelin plays a role to regulate EEC adhesion to the oocyte through an intracellular signal transduction pathway, but not by acting as a secretory protein.

In cultured EEC line (Ishikawa cells), treatment with the combination of estradiol and progesterone (E2P4) or SAHA, one of the HDACIs, induces glycodelin expression at the mRNA and protein levels [28]. In this in vitro study, hormone‐ or HDACI‐induced glycodelin has caused transdifferentiation of an EEC line, observed by flattened and wide‐spread morphological changes and up‐regulation of glycogen synthesis. Furthermore these alterations have been completely abrogated by glycodelin gene silencing using small interference RNA (siRNA) [28]. This study shows the possibility that glycodelin is involved in endometrial receptivity before oocyte apposition.

For fertilized oocytes, human implantation is a complex process, involving apposition and adhesion onto EECs followed by invasion and penetration into EECs. For successful pregnancy, adhesion between the oocyte and EECs is required after apposition. Glycodelin induced by E2P4 or SAHA has enhanced adhesion ability [5], while glycodelin in culture media can not be measured in Ishikawa cells [46]. Furthermore, transfection of glycodelin cDNA lacking the N‐terminal putative signal peptide has also enhanced adhesion ability, and the enhancement of adhesions by stimulation of E2P4 or SAHA can be completely abrogated by glycodelin siRNA transfection [5]. Taken together, glycodelin regulates EEC adhesion ability against oocytes via an intracellular signal transduction pathway without action as a secretory protein.

Increased glycodelin expression is timed to endometrial receptivity, whereas glycodelin‐A in culture media has suppresses invasion of immotile cytotrophoblast cells and the choriocarcinoma cell line, JEG‐3, by down‐regulation of the extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK)/c‐Jun signaling pathway. Furthermore, the suppressive mechanism by glycodelin‐A has been mediated by interaction with sialic acid binding immunoglobulin‐like lectins (Siglec)‐6 [47]. A member of the Siglec protein family is known as the cell–cell interaction protein in immune cells and Siglec‐6 is a trophoblast‐specific protein.

In an in vitro implantation assay using Ishikawa cells and spheroids of JAR cells (choriocarcinoma cell line) for an embryo model, spreading away onto the Ishikawa monolayer and occupying the space by JAR cells mimics invasion of trophoblasts. In E2P4‐ or SAHA‐treated Ishikawa cells, JAR spheroids has spread more widely than control Ishikawa cells [48]. This phenomenon is probably due to acceleration of Ishikawa cell motility by stimulation of ovarian steroid hormones or HDACI [49]. EEC motility is accelerated or suppressed by transfection of glycodelin cDNA or siRNA, respectively [49]. These studies indicate that glycodelin of EECs affect trophoblast invasion regulating the balance between suppression of trophoblast cell motility (paracrine pathway) and acceleration of EEC cell motility (intracellular pathway).

Overexpression of glycodelin in Ishikawa cells has resulted in reduction of EEC proliferation through up‐regulation of p21, p27, and p16 and thereby G1/S stop [50]. Furthermore, progesterone‐induced inhibition of Ishikawa cell growth has been attenuated by glycodelin siRNA transfection [50]. Glycodelin has a possible potential to assist trophoblast invasion and penetration through EEC apoptosis and suppression of EEC proliferation.

Summary

After glycosylation and dimerization, glycodelin protein acts as a multiple‐regulator (immunosuppression, fertilization, and implantation) and a director to orchestrate the complex, step‐by‐step process of fertilization and implantation. There remain a number of unknown functions and mechanisms to be elucidated; however, collective evidence of glycodelin function and regulation should be applied for reproductive medicine, such as infertility, recurrent miscarriage, and anti‐conception.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rika Shibata for her secretarial work. This work was supported in part by grants‐in‐aid for scientific research C 24592484 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

References

- 1.Tatarinov Iu S, Krivonosov SK, Petrunin DD, Shevchenko OP. Comparative immunochemical analysis of specific beta globulins of the “pregnancy zone” of the humans and other mammals. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1976; 82:1223–5. [PubMed]

- 2. Kamarainen M, Julkunen M, Seppala M. HinfI polymorphism in the human progesterone associated endometrial protein (PAEP) gene. Nucleic Acids Res, 1991, 19, 5092 10.1093/nar/19.18.5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garde J, Bell SC, Eperon IC. Multiple forms of mRNA encoding human pregnancy‐associated endometrial alpha 2‐globulin, a beta‐lactoglobulin homologue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1991, 88, 2456–2460 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Kamarainen M, Salo J, Seppala M. Multiple forms of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding glycodelin in male genital tract. Lab Invest, 1997, 76, 683–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uchida H, Maruyama T, Ohta K, Ono M, Arase T, Kagami M et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor‐induced glycodelin enhances the initial step of implantation. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 2615–2622 10.1093/humrep/dem263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamarainen M, Halttunen M, Koistinen R, Boguslawsky K, Smitten K, Andersson LC et al. Expression of glycodelin in human breast and breast cancer. Int J Cancer, 1999, 83, 738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Julkunen M, Rutanen EM, Koskimies A, Ranta T, Bohn H, Seppala M. Distribution of placental protein 14 in tissues and body fluids during pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 1985, 92, 1145–1151 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb03027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Julkunen M, Koistinen R, Suikkari AM, Seppala M, Janne OA. Identification by hybridization histochemistry of human endometrial cells expressing mRNAs encoding a uterine beta‐lactoglobulin homologue and insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐1. Mol Endocrinol, 1990, 4, 700–707 10.1210/mend-4-5-700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamarainen M, Riittinen L, Seppala M, Palotie A, Andersson LC. Progesterone‐associated endometrial protein‐a constitutive marker of human erythroid precursors. Blood, 1994, 84, 467–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrow DM, Xiong N, Getty RR, Ratajczak MZ, Morgan D, Seppala M et al. Hematopoietic placental protein 14. An immunosuppressive factor in cells of the megakaryocytic lineage. Am J Pathol, 1994, 145, 1485–1495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tse JY, Chiu PC, Lee KF, Seppala M, Koistinen H, Koistinen R et al. The synthesis and fate of glycodelin in human ovary during folliculogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod, 2002, 8, 142–148 10.1093/molehr/8.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Julkunen M, Wahlstrom T, Seppala M. Human fallopian tube contains placental protein 14. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1986, 154, 1076–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Julkunen M, Wahlstrom T, Seppala M, Koistinen R, Koskimies A, Stenman UH et al. Detection and localization of placental protein 14‐like protein in human seminal plasma and in the male genital tract. Arch Androl, 1984, 12 (Suppl) 59–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Dell A, Morris HR, Easton RL, Patankar MS et al. Glycodelin from seminal plasma is a differentially glycosylated form of contraceptive glycodelin‐A. Mol Hum Reprod, 1996, 2, 759–765 10.1093/molehr/2.10.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Julkunen M, Koistinen R, Sjoberg J, Rutanen EM, Wahlstrom T, Seppala M. Secretory endometrium synthesizes placental protein 14. Endocrinology, 1986, 118, 1782–1786 10.1210/endo-118-5-1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kao LC, Tulac S, Lobo S, Imani B, Yang JP, Germeyer A et al. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology, 2002, 143, 2119–2138 10.1210/en.143.6.2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li TC, Dalton C, Hunjan KS, Warren MA, Bolton AE. The correlation of placental protein 14 concentrations in uterine flushing and endometrial morphology in the peri‐implantation period. Hum Reprod, 1993, 8, 1923–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riittinen L, Julkunen M, Seppala M, Koistinen R, Huhtala ML. Purification and characterization of endometrial protein PP14 from mid‐trimester amniotic fluid. Clin Chim Acta, 1989, 184, 19–29 10.1016/0009-8981(89)90253-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chiu PC, Chung MK, Koistinen R, Koistinen H, Seppala M, Ho PC et al. Cumulus oophorus‐associated glycodelin‐C displaces sperm‐bound glycodelin‐A and ‐F and stimulates spermatozoa‐zona pellucida binding. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282, 5378–5388 10.1074/jbc.M607482200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown SE, Mandelin E, Oehninger S, Toner JP, Seppala M, Jones HW Jr. Endometrial glycodelin‐A expression in the luteal phase of stimulated ovarian cycles. Fertil Steril, 2000, 74, 130–133 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00586-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bell SC, Hales MW, Patel SR, Kirwan PH, Drife JO, Milford‐Ward A. Amniotic fluid concentrations of secreted pregnancy‐associated endometrial alpha 1‐ and alpha 2‐globulins (alpha 1‐ and alpha 2‐PEG). Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 1986, 93, 909–915 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb08007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li TC, Ling E, Dalton C, Bolton AE, Cooke ID. Concentration of endometrial protein PP14 in uterine flushings throughout the menstrual cycle in normal, fertile women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 1993, 100, 460–464 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Julkunen M, Apter D, Seppala M, Stenman UH, Bohn H. Serum levels of placental protein 14 reflect ovulation in nonconceptional menstrual cycles. Fertil Steril, 1986, 45, 47–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seppala M, Ronnberg L, Karonen SL, Kauppila A. Micronized oral progesterone increases the circulating level of endometrial secretory PP14/beta‐lactoglobulin homologue. Hum Reprod, 1987, 2, 453–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Critchley HO, Chard T, Olajide F, Davies MC, Hughes S, Wang HS et al. Role of the ovary in the synthesis of placental protein‐14. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1992, 75, 97–100 10.1210/jc.75.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reshef E, Lei ZM, Rao CV, Pridham DD, Chegini N, Luborsky JL. The presence of gonadotropin receptors in nonpregnant human uterus, human placenta, fetal membranes, and decidua. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1990, 70, 421–430 10.1210/jcem-70-2-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tseng L, Zhu HH, Mazella J, Koistinen H, Seppala M. Relaxin stimulates glycodelin mRNA and protein concentrations in human endometrial glandular epithelial cells. Mol Hum Reprod, 1999, 5, 372–375 10.1093/molehr/5.4.372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uchida H, Maruyama T, Nagashima T, Asada H, Yoshimura Y. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce differentiation of human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells through up‐regulation of glycodelin. Endocrinology, 2005, 146, 5365–5373 10.1210/en.2005-0359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okamoto N, Uchida A, Takakura K, Kariya Y, Kanzaki H, Riittinen L et al. Suppression by human placental protein 14 of natural killer cell activity. Am J Reprod Immunol, 1991, 26, 137–142 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1991.tb00713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeschke U, Mylonas I, Richter DU, Streu A, Muller H, Briese V et al. Human amniotic fluid glycoproteins expressing sialyl Lewis carbohydrate antigens stimulate progesterone production in human trophoblasts in vitro. Gynecol Obstet Invest, 2004, 58, 207–211 10.1159/000080073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jeschke U, Richter DU, Walzel H, Bergemann C, Mylonas I, Sharma S et al. Stimulation of hCG and inhibition of hPL in isolated human trophoblast cells in vitro by glycodelin A. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2003, 268, 162–167 10.1007/s00404-002-0360-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kayisli UA, Selam B, Guzeloglu‐Kayisli O, Demir R, Arici A. Human chorionic gonadotropin contributes to maternal immunotolerance and endometrial apoptosis by regulating Fas–Fas ligand system. J Immunol, 2003, 171, 2305–2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee CL, Chiu PC, Lam KK, Siu SO, Chu IK, Koistinen R et al. Differential actions of glycodelin‐A on Th‐1 and Th‐2 cells: a paracrine mechanism that could produce the Th‐2 dominant environment during pregnancy. Hum Reprod, 2011, 26, 517–526 10.1093/humrep/deq381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roberts AI, Devadas S, Zhang X, Zhang L, Keegan A, Greeneltch K et al. The role of activation‐induced cell death in the differentiation of T‐helper‐cell subsets. Immunol Res, 2003, 28, 285–293 10.1385/IR:28:3:285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee CL, Chiu PC, Lam KK, Chan RW, Chu IK, Koistinen R et al. Glycodelin‐A modulates cytokine production of peripheral blood natural killer cells. Fertil Steril, 2010, 94, 769–771 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gneist N, Keck G, Zimmermann A, Trinkaus I, Kuhlisch E, Distler W. Glycodelin binding to human ejaculated spermatozoa is correlated with sperm morphology. Fertil Steril, 2007, 88, 1358–1365 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chiu PC, Chung MK, Tsang HY, Koistinen R, Koistinen H, Seppala M et al. Glycodelin‐S in human seminal plasma reduces cholesterol efflux and inhibits capacitation of spermatozoa. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280, 25580–25589 10.1074/jbc.M504103200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohen‐Dayag A, Tur‐Kaspa I, Dor J, Mashiach S, Eisenbach M. Sperm capacitation in humans is transient and correlates with chemotactic responsiveness to follicular factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1995, 92, 11039–11043 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chiu PC, Koistinen R, Koistinen H, Seppala M, Lee KF, Yeung WS. Binding of zona binding inhibitory factor‐1 (ZIF‐1) from human follicular fluid on spermatozoa. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278, 13570–13577 10.1074/jbc.M212086200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yanagimachi R. Fertility of mammalian spermatozoa: its development and relativity. Zygote, 1994, 2, 371–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oehninger S, Coddington CC, Hodgen GD, Seppala M. Factors affecting fertilization: endometrial placental protein 14 reduces the capacity of human spermatozoa to bind to the human zona pellucida. Fertil Steril, 1995, 63, 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen DB, Hilsenrath R, Yang ZM, Le SP, Kim SR, Chuong CJ et al. Leukaemia inhibitory factor in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle: cellular origin and action on production of glandular epithelial cell prostaglandin in vitro. Hum Reprod, 1995, 10, 911–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Damario MA, Lesnick TG, Lessey BA, Kowalik A, Mandelin E, Seppala M et al. Endometrial markers of uterine receptivity utilizing the donor oocyte model. Hum Reprod, 2001, 16, 1893–1899 10.1093/humrep/16.9.1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang HY, Xing FQ, Chen SL. Expression of trophinin in the cycling endometrium and its association with infertility. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao, 2002, 22, 539–541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kliman HJ, Feinberg RF, Schwartz LB, Feinman MA, Lavi E, Meaddough EL. A mucin‐like glycoprotein identified by MAG (mouse ascites Golgi) antibodies. Menstrual cycle‐dependent localization in human endometrium. Am J Pathol, 1995, 146, 166–181 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arnold JT, Lessey BA, Seppala M, Kaufman DG. Effect of normal endometrial stroma on growth and differentiation in Ishikawa endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res, 2002, 62, 79–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lam KK, Chiu PC, Lee CL, Pang RT, Leung CO, Koistinen H et al. Glycodelin‐A protein interacts with Siglec‐6 protein to suppress trophoblast invasiveness by down‐regulating extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK)/c‐Jun signaling pathway. J Biol Chem, 2011, 286, 37118–37127 10.1074/jbc.M111.233841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Uchida H, Maruyama T, Nishikawa‐Uchida S, Oda H, Miyazaki K, Yamasaki A et al. Involvement of epithelial mesenchymal transition of human endometrial epithelial cells in human embryo implantation: evidence from studies using in vitro model. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287, 4441–4450 10.1074/jbc.M111.286138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Uchida H, Maruyama T, Ono M, Ohta K, Kajitani T, Masuda H et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors stimulate cell migration in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells through up‐regulation of glycodelin. Endocrinology, 2007, 148, 896–902 10.1210/en.2006-0896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ohta K, Maruyama T, Uchida H, Ono M, Nagashima T, Arase T et al. Glycodelin blocks progression to S phase and inhibits cell growth: a possible progesterone‐induced regulator for endometrial epithelial cell growth. Mol Hum Reprod, 2008, 14, 17–22 10.1093/molehr/gam081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]