Abstract

Background

Obesity influences all aspects of the life of obese patients physically, psychologically, socially and monetarily, it is not only a disease but rather a beginning point of a group of ailments and inabilities, which gradually impacts and changes all aspects of their life.

Objectives

The changes in the Quality of life in respect to the amount of access weight lost after sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients, materials and methods

A prospective longitudinal study evaluating 40 female patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy within 4 years, starting from July 4th, 2012 up to July 5th, 2016.

Results

More than three-quarter of the patients were not satisfied with their body before their operation, but six to twelve months after their weight loss; (N = 36, 90%) of them were satisfied with their new body image. Half of the patients were unhappy before their operation, but twelve months later (N = 31, 77.5%) of them became much happier. Regarding satisfaction with the body image, noticeable improvement occurred since (N = 36, 90%) of them were satisfied with their new body image. While, most of them have had low self-esteem and (N 27, 67.5%) of the patients had no self-esteem at all, 12 months after the operation (N = 35, 87.5%) felt great improvement in their self-esteem (p-value = .040). A significant decrease in appetite was noticed in (N = 39, 97.5%) of the patients after 12 months.

Conclusion

Significant changes in the parallel pattern to the extent of EWL were noticed in the quality of life of morbidly obese patients after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Keywords: A pattern, Parallel, Reverse-pattern, Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Quality of life, Non-health quality of life, Morbid obesity

Highlights

-

•

Patient health improves after weight loss in terms of metabolic, macrovascular, and microvascular disease, results in better quality of life.

-

•

Obesity is widely known as a major health risk factor, and bariatric surgery has proved to be significantly effective and safe procedure.

-

•

Bariatric surgery results in a sustainable and effective reduction in body weight, which provides an improvement in the quality of life.

-

•

Obesity is a beginning point of a group of ailments and inabilities, which gradually impacts and changes all aspects of their life.

-

•

In a rundown, bariatric surgery is related to an improvement in insulin achievement, fat tissue reactive substances, and QoL.

1. Introduction

Obesity is a worldwide medical issue [1], achieving pestilence extents and is rapidly turning into a noteworthy general wellbeing concern [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Morbid obesity is related to illnesses and medical conditions such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary illness, stroke, hypertension and malignancies, joint degeneration, liver disorders, venous stasis and urinary incontinence [6].

The exponential increment in obesity worldwide has brought into concentration the absence of compelling techniques for treatment or prevention [1].

Customary strategies for weight reduction, for example, change in eating routines and exercise, are less compelling than weight loss surgery in the corpulent populace. Just surgery brings about sustained weight reduction for super-obese patients, being a successful means in the treatment of gruesome obesity [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. Prompting sturdy weight reduction, huge and kept up in the long haul and improves higher weight-related hazard factors [4,7,8].

Bariatric surgery is related to a moderately low number of complexities and seems to bring about a decrease in mortality hazards due to the determination of comorbidities. Since the presentation of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, (LSG) has increased, expanding reliability as a remaining solitary essential bariatric method [9]. The relative straightforwardness of the operation, the absence of a foreign body or requirement for numerous postoperative changes, and a worthy safety profile are highlights that interest to numerous patients and bariatric specialists [10,11].

Notwithstanding weight reduction, understanding wellbeing enhances as far as metabolic, macrovascular, and microvascular illnesses, brings about better personal satisfaction, alongside psychosocial prosperity [4,7,8,10].

LSG altogether enhances strolling and additionally a scope of movement of the joints, encouraging a physical movement of obese patients that might cause stamped weight reduction after bariatric surgery [12,13].

In a rundown, bariatric surgery is related to an improvement in insulin achievement, fat tissue reactive substances, and QoL [14].

2. Patients and methods

Through prospective observational work which is fully compliant with the STROCSS criteria [15], evaluating 40 morbidly obese married female patients with age ranging from 25-34 years with a mean of 27 years. Their mean Body Mass Index (BMI) is 43kg/m2 (40–50). Who underwent Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) within 4 years from July 4th, 2012 up to July 5th, 2016.

Here we aimed in eliminating gender differences in the answers to our questionnaire, thus we choose all the patients from the same gender, as it was discovered; there are actually differences in the way women's and men's brains are structured and in the way they react to events and stimuli: indicating that women typically excel in language-based subjects and in language-associated thinking [16].

Informed consents were signed by all the patients. The study was endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Medical College in the University of Sulaimani.

All patients underwent complete evaluation before the operation, including endoscopy and abdominal ultrasonography. Additional investigations were performed according to the risk profiles of each individual patient.

Patients were followed up after one week, one month, monthly for 3 more months after the operation and continue follow up bimonthly to the present day.

An explained questionnaire based on Five-Point Likert scale [17,18], arranged in the form of indirect statements in order to minimize central tendency bias and acquiescence bias. Three people conducted the interview, one of them was a female senior nurse, to ensure the comfortability of patients in answering the questions. Explanations were provided to the patients and the reason behind the interview in order to obtain the informed consent. Patients were encouraged to respond to the questions with their true feelings, any positive as well as any negative feelings they might have had.

In the interviews; data was collected regarding the quality of their life before the operation and 6 & 12 months after the operation, questions were declared and directed towards the importance of exercise and loss of weight. The patients were also asked about their social life, their psychological feelings, their self-esteem, their appetite, ease of movement (different postures in everyday activities or during sitting). Answers to each question were rated as (not at all, just a little, not so much, much and too much).

The collected data was analyzed by SPSS version 21.

3. Results

After the collection and the analysis of the data and the tabulation of it, we compared the BMI, EWL and their responses to each question of the questionnaire regarding the direction of the changes as shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7.

Table 1.

Showing loss of grades of BMI in the patients in 3, 6 and 12 months after the operation.

| Number of Patients | BMI, before surgery | BMI, 3 months after the operation | BMI, 6 months after the operation | BMI, 12 months after the operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 41.5 ± 1.5 | 35.75 ± 0.75 | 33.5 ± 0.50 | 31.5 ± 0.50 |

| 8 | 44.5 ± 0.5 | 35.50 ± 1.50 | 33.5 ± 1.50 | 32.0 ± 1.00 |

| 7 | 47.0 ± 1.0 | 38.25 ± 0.25 | 35.0 ± 1.00 | 34.0 ± 1.00 |

| 5 | 49.5 ± 0.5 | 40.00 ± 1.00 | 37.0 ± 1.00 | 36.5 ± 1.50 |

Note: Half of the patients lost (5.70 ± 1.12 kg/m2) of their BMI in 3,6 and 12 months respectively.

Table 2.

Showing range of access weight before surgery and the percentage of access weight loss (%EWL) in the patients after 3, 6 and 12 months after the operation.

| EBW, before surgery | %EWL, after 3 months | %EWL, after 6 months | %EWL, after 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| 58.75 ± 16.25 kg | 33.25 ± 2.25% | 45.15 ± 3.75% | 49.2 ± 4.30 |

Note: All the patients lost access body weight (EBW) in 3,6 and 12 months in the form of EWL (33.25 ± 2.25%), (45.15 ± 3.75%) and (49.2 ± 4.30%) respectively.

Table 3.

Aspects of QOL before LSG.

| Aspects of QOL | Scoring |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | Just a little | Not so much | Much | Too much | ||

| Feeling sad | 1 | 0 | 2 | 35 | 2 | .045 |

| Importance to lose weight | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 30 | .037 |

| Importance of regular exercise | 5 | 6 | 17 | 7 | 5 | .060 |

| Importance to be sexually attractive or to have regular sex. | 10 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 7 | .049 |

| Importance to have better body shape, wearing the ordinary fashion for their age | 0 | 5 | 24 | 6 | 5 | .078 |

| Ease to take any posture comfortably like putting leg on leg | 27 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | .043 |

| Shortness of breath on minimal exertion | 1 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 11 | .052 |

| Excessive sweating | 8 | 1 | 5 | 16 | 10 | .051 |

| Sleepiness | 10 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 8 | .056 |

| Spending good time with friends | 32 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | .042 |

| Nervousness, embracing by unimportant matters | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 33 | .050 |

| Hearing sarcasm or teasing by others | 2 | 2 | 6 | 23 | 7 | .064 |

| Negative thoughts | 2 | 6 | 4 | 19 | 9 | .048 |

| Controlling satiety and food intake | 35 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | .035 |

| Embarrassed by prompt discussions in the family or unimportant matters | 1 | 3 | 6 | 23 | 7 | .041 |

| Any physical obstacle for obtaining the job they like, | 5 | 9 | 7 | 16 | 3 | .065 |

| Any physical obstacle for success in their jobs | 4 | 16 | 10 | 8 | 2 | .071 |

| Any suicidal thoughts | 5 | 8 | 19 | 7 | 2 | .076 |

| Afraid from what they hear and see from mass media | 20 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 8 | .070 |

| Becoming more apprehensive | 1 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 25 | .070 |

| Shyness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 10 | |

| Body weight narrowed their social circle,introversion (Loneliness) | 1 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 21 | .035 |

| Decreased opportunity for spending time with friends | 1 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 20 | .050 |

| Feeling uneasy in showing their bodies | 13 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 17 | .093 |

| Self conscious in achieving things | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 22 | .065 |

Note: Before the operations most of the patients were highly motivated to loss weight, (N = 30, 75%) knew the importance of weight loss, while (N = 33, 82.5%) were nervous and embracing by unimportant matters, at same time (N = 25, 62,5%) were severely apprehensive and (N = 21, 52.5%) had little opportunity for spending time with friends.

Table 4.

Aspects of QOL three months after LSG.

| Aspects of QOL | Scoring |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | Just a little | Not so much | Much | Too much | ||

| Feeling happy | 20 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 0.041 |

| Body image satisfaction | 34 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Self esteem | 27 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | |

| Feeling sexually attractive | 24 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Married people having regular sex | 28 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Spending good time with friends | 25 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nervousness, embracing by unimportant matters | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hearing sarcasm or teasing by others | 28 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Negative thoughts | 29 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Decrease in appetite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 37 | |

| Ease to take any posture comfortably such as crossing their legs | 21 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

Numerous patients (N = 37, 92.5%) claimed improvements in important aspects of their life, such as (decreased appetite), while a small number (N = 7, 17.5%) claimed to be happier.

Table 5.

Aspects of QOL six months after LSG.

| Aspects of QOL | Scoring |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | Just a little | Not so much | Much | Too much | ||

| Feeling happy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 30 | .034 |

| Satisfied with their new body image | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 32 | |

| Improved self esteem | 1 | 2 | 5 | 32 | ||

| Feeling sexually attractive | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 33 | |

| Better or regular sex | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 28 | |

| Spending more time with friends | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 26 | |

| Nervousness, embracing by unimportant matters | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hearing sarcasm or teasing by others | 28 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Negative thoughts | 29 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 37 | |

| Ease to take any posture comfortably such as crossing their legs | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 35 | |

Note: Number of patients with decreased appetite (N = 37, 92.5%) remain the same after 3 months, while most have improved in other important aspects of life i.e; (N = 30, 75%) feeling happy, (N = 32, 80%) satisfied with their new body image, (N = 32, 80%) had improved self esteem, (N = 33, 82.5%) were feeling sexually attractive and (N = 28, 70%) had better or regular sex.

Table 6.

Aspects of QOL one year after LSG.

| Aspects of QOL | Scoring |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | Just a little | Not so much | Much | Too much | ||

| Feeling happy | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 31 | .040 |

| Satisfied with the new body image | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 36 | |

| Improved self esteem | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 35 | |

| Feeling sexually attractive | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 36 | |

| Married people having better or regular sex | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 32 | |

| Spending more time with friends | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 35 | |

| Nervousness, embracing by unimportant matters | 33 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hearing sarcasm or teasing by others | 37 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Negative thoughts | 33 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 39 | |

| Ease to take any posture comfortably such as crossing their legs | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 33 | |

Note: Half of the patients were unhappy before the operation, but twelve months later (N = 31, 77.5%) of them became much happier, regarding satisfaction with their body image; noticeable improvement occurred, (N = 36, 90%) of them were satisfied with their new body image. While, most of them have had low self-esteem and(N27, 67.5%)of the patients had no self-esteem prior to the surgery, 12 months later (N = 35, 87.5%) felt great improvement in their self-esteem (p-value = .040). A significant decrease in appetite was noticed in (N = 39, 97.5%) of the patients after 12 months.

Table 7.

Aspects of QOL before the operation,6 months and 12 months after the operations.

| Aspects of QOL | Scoring |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 5 (much) | ||||

| Before surgery | After 6 months | After 12 months | ||

| Feeling happy | 7 | 30 | 31 | .034 |

| 17.5% | 75.0% | 77.5% | ||

| Satisfied with their body image | 1 | 32 | 36 | |

| 2.5% | 80.% | 90.0% | ||

| Improved self esteem | 3 | 32 | 35 | |

| 7.5% | 80.0% | 87.5% | ||

| Feeling sexually attractive | 1 | 33 | 36 | |

| 2.5% | 82.5% | 90.0% | ||

| Better or regular sex | 3 | 28 | 32 | |

| 7.5% | 70.0% | 80.0% | ||

| Spending more time with friends | 0 | 26 | 35 | |

| 0.0% | 65.0% | 87.5% | ||

| Nervousness, embracing by unimportant matters | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2.5% | 2.5% | 0.0% | ||

| Hearing sarcasm or teasing by others | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2.5% | 2.5% | 0.0% | ||

| Negative thoughts | 10 | 1 | 0 | |

| 26% | 2.5% | 0.0% | ||

| Decreased appetite | 2 | 37 | 39 | |

| 5.0% | 92.5% | 97.5% | ||

| Ease to take any posture comfortably such as crossing their legs | 5 | 35 | 37 | |

| 12.5% | 87.5% | 92.5% | ||

Note: To simplify, the above table shows extent of the improvements in 11 aspects of the QOL in the patients by comparing data before the operations to data 6 and 12 months after the operations.

Regarding the preoperative level of QOL of the patients, scoring was different for each question, i.e; 87.5% of them had answered with (Score 1 = not at all) for (Controlling satiety and food intake). Those who had higher scoring (Score 2 = just a little) were 40% for (Any physical obstacle for success in their jobs). But 60% of the patients gave answers with a score (3 = not so much) for (Importance to have better body shape, wearing the ordinary fashion for their age). While 87.5% of the patients gave answers (Score 4 = much) for (feeling sad). For higher scoring 75% and 82.5% of the patients gave answers with (Score 5 = too much) for (importance of weight loss) and (nervousness and embracing by unimportant matters) as shown in (Table 3).

Some aspects of QOL have been selected for comparison before and after operation in their scores, we included the questions which are comparable and could be asked before and later after the operation visits, details are shown in (Table 4).

Score details are shown in Table 5, Table 6, which represents changes in QOL, 6 and 12 months after the operation. For more clarification; the highest and lowest scores (1 = not at all & 5 = much) are detailed in Table 6, to show the changes in those aspects over time and with weight loss in the patients.

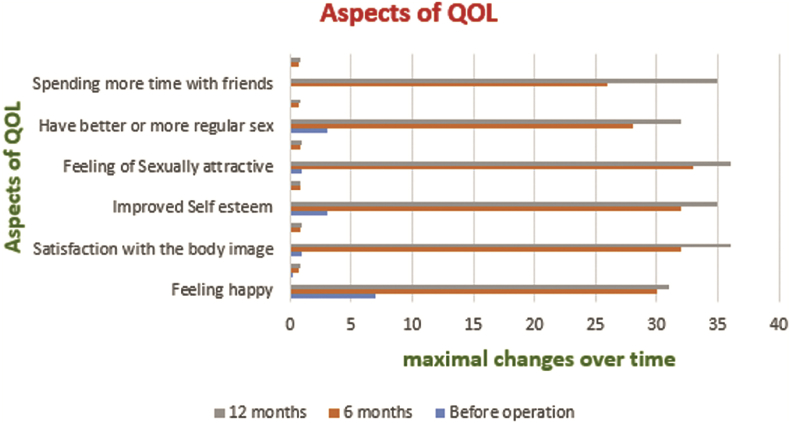

Improvement in most aspects of the life of the patients has been noticed. Their sexual attractiveness became better and sex became regular from (N = 16, 40%) and (N = 12, 30%) to (N = 39, 97.5% and N = 32, 80%) respectively as shown in (Table 7 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Changes in aspects of QOL over time.

Negative thoughts in the patients declined from (N = 10, 25%), to (N = 0, 0%) after 12 months from their operations. Their appetite decreased and their feeling of satiety increased from (N = 2, 5%) to (N = 39, 97.5%). While spending time with their friends and their social life improved from (N = 0, 0.0%) to (N = 35, 87.5%). Before the operation only (N = 5, 12.5%) felt easiness in making postures comfortably such as crossing their legs, while (N = 1, 87.5%) and (N = 37, 92.5%) of them felt this ease after their operations in 6 and 12 months respectively.

4. Discussion

Obesity is widely known as a major health risk factor, and bariatric surgery has proved to be significantly effective and a safe procedure [8], results in sustainable and effective reduction in body weight [19,20], on a long-term basis [21], which provides meaningful weight loss and improvement in the quality of life [22], which is an effective alternative to the current standard procedures [23].

The ultimate goal of bariatric surgery is weight loss and the resolution of obesity-related comorbidities to improve psychosocial functioning and quality of life (QOL) in morbidly obese patients [24]. QOL will be improved after surgery because surgical treatment achieved significant weight loss [25], which may be seen as early as 3 months after surgery. By 6 months after surgery, patients may improve to the extent of the same quality of life scores as the reference population [26].

Searching literature one may feel that there is a lack of adequate prospective data on quality-of-life (QOL) in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [19], which made it worthy to explore this aspect of LSG.

The patients in the current work have lost (33.25 ± 2.25%), (45.15 ± 3.75%), (49.2 ± 4.30) of their EW after 3, 6 and 12 months respectively. The more and sustained the weight loss is, the greater will be the improvement in QOL [19,25,[27], [28], [29]].

A significant weight reduction three and six months following surgery, with better body image, more mobility and less teasing by others had led to an improved quality of life in all indicated areas [21]. Weight reduction was the cause of positive changes in quality of life [20,21].

The patients started losing weight from the first week after the operation, their weight loss became noticeable as early as 3 months and continued. Significant improvements showed in the quality of their life in this period in a parallel pattern to the extent of the EWL.

Some of the patients regained up to 5 kilograms of their weight in the last 6 months of the year of follow-up, as losing weight slowed in the last 6 months of that year of evaluation as shown in (Table 1, Table 2), meanwhile improvement in their quality of life slowed, for example (Feeling of happiness declined and their appetite was increasing) which was parallel to the decline in loss of excess weight as shown in (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7).

The patients, although having progressive and sustained EWL noticed to be comparable to other studies [30,31], except for later minor weight gain in 2nd six months of the year, while in other studies, this minor gain in weight was in the 1st six months, shown in (Table 8). This is not in line of the literature as this small regain of weight may occur much earlier as claimed by Lee YC et al. [32], that there may be an initial small regain in weight after initial EWL [30,31].

Table 8.

Comparison of EWL before and after surgery between the current work and some other papers from literature.

| Studies | Number of patients | After 3 months | After 6 months | After 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paul Brunault et al. [30] | 29 | 35.7 ± 14.3% | – | 43.8 ± 17.8% |

| Andrzej Lehmann et al. [31] | 202 | 30.1% | −34.6% | 47.5% |

| Martin DJ et al. [33] | 292 | −49% | 64% | 76% |

| Current paper | 40 | 31–35.5% | 41.4–48.9% | 44.9–53.5% |

Note: the sample of the participants is smaller than (Andrzej Lehmann et al., Martin DJ et al.), but it is larger than (Paul Brunault et al.). The result of the current work three months after the operations is close to (Andrzej Lehmann et al. and Paul Brunault et al.) but higher than (Martin DJ et al.). While it is close to 2/3 of the EWL in (Martin DJ et al.)’s work 6 and 12 months after the operations, and comparable to (Andrzej Lehmann et al.) one year after the operations.

The EWL of the patients were evaluated up to twelve months, which is in line with most studies in literature [22,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34]], as shown in (Table 8), although some studies prefer to extend this evaluation period to 24 months [19,24].

Improvements in weight may lead to the assumption that physical activity will increase, as LSG patients had a better physical function, higher energy levels, and the perception of better general health [32].

Noticeable changes were found after 1 year in all aspects of quality of life of morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [35], in a parallel pattern to the extent of EWL as early as three months after the operation.

Strengths and limitations;

A. Strengths:

-

1.

All the selected patients were from the same gender, all married women who were very frank in the interview and the discussion of the questionnaire prior to the operation and at 3, 6, and 12 months after the operation.

-

2.

Exploring most aspects of non-health related QOL.

-

3.

Using five-point Likert Scale, which is simple and gives freedom to the patients in expressing their true feelings.

-

4.

Female personnel were present during the interviews which puts these eastern ladies more at ease.

-

5.

Exclusion of patients who had co-morbidity or locomotors disabilities in order not to affects the results.

-

6.

This is one of the few papers in literature which studies changes in OQL of eastern patients after bariatric surgery.

B. Limitations:

-

1.

Small number of participants.

-

2.

Only one year follow up of the patients.

5. Conclusion

Significant changes in a parallel pattern to the extent of EWL were noticed in the quality of life of morbidly obese patients after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Ethical approval

Research ethics approval was provided by Ethic committee the University of Sulaimani- College of medicine (12/6/17).

Funding

No any sources of funding for the research.

Author contribution

Study design: Hiwa Ahmed.

Data collection: Hiwa Ahmed.

Statistical analysis: Dr. Abdulfatah Muhamad

Writing first draft of manuscript: Hiwa Ahmed.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Guarantor

Hiwa Ahmed.

Unique identifying number (UIN)

UIN: research registry 3274.

Trial registry number

No it is not.

Informed consent

Informed consents were obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Three people conducted the interview, one of them was a female senior nurse, to ensure the comfortability of patients in answering the questions. Explanations were provided to the patients and the reason behind the interview in order to obtain the informed consent.

Acknowledgment

I would like to express my gratitude to my patients for their participation and cooperation.

I would also like to thank all the medical and paramedical staff at Hatwan Private Hospital for Endoscopic Surgery and the bariatric surgical unit in Sulaimani Teaching Hospital for their specialized offered assistance.

References

- 1.Dumon Kristoffel R., Murayama Kenric M. Bariatric surgery outcomes. Surg. Clin. N. Am. December 2011;91(6):1313–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotter Samantha Ann, Cantrell Wendy, Fisher Barry. Efficacy of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. University medical center USA. Obes. Surg. 2005;15:1316–1320. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maggard Melinda A., Shugarman Lisa R., Suttorp Marika. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;142:547–559. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston Edward H., Huerta Sergio, Arthur Denice. Male gender is a predictor of morbidity and age a predictor of mortality for patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. The UCLA bariatric surgery program, and the UCLA center for human nutrition. Ann. Surg. 2002;236(5):567–582. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zachari Eleni, Sioka Eleni, Tzovaras George. first ed. Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa; Greece: 2012. Venous Thromboembolism in Bariatric Surgery, Pulonary Embolism; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guh Daphne P., Zhang Wei, Bansback Nick. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden C.L., Carroll, Curtin L.R. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tham Ji Chung, le Roux Carel W. Benefits of bariatric surgery and perioperative surgical safety. EMJ Eur. Med. J. November 2015:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brethauer Stacy A., Batayyah Esam S. 25 November 2014. Fifteen Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Outcomes Minimally Invasive Bariatric Surgery; pp. 143–150. SBN: 978-1-4939-1636-8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.CHOUILLARD E.L.I.E. 10-Years results of sleeve gatsrectomy as compared to roux en Y gastric bypass in patients with morbid obesity a case control study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. August 2016;12(issue 7):S219. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanti Hiba, Obeidat Firas. The impact of family members on weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016;12(8):1499–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courcoulas Anita P., Yanovski Susan Z., Bond Denise. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery. A national institutes of health symposium. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(12):1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebibo Lionel, Verhaeghe Pierre, Tasseel-Ponche Sophie. Does sleeve gastrectomy improve the gait parameters of obese patients? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016;12(8):e63–e72. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.023. 1441-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navaneethan Sankar D., Malin Steven K. Bariatric surgery, kidney function, insulin resistance, and adipokines in patients with decreased GFR: a cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015 February;65(2):345–347. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Vella-Baldacchino M., Thavayogan R., Orgill D.P., for the STROCSS Group The STROCSS statement: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. October 2017;46:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.08.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensley Amber. 10 big differences between Men's and Women's brains masters of healthcare. January 16th, 2009. http://www.mastersofhealthcare.com/blog/2009/10-big-differences-between-mens-and-womens-brains/ visited on 10/11/20127.

- 17.Surveymonkey, Likert Scale: What It Is & How to Use It, SurveyMonkey https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/likert-scale/ visited on 10/11/2017.

- 18.Allen Elaine, Seaman Christopher A. STATISTICS roundtable-likert scales and data, quality progress. 2007 July. http://asq.org/quality-progress/2007/07/statistics/likert-scales-and-data-analyses.html visited on 11/11/2017.

- 19.Charalampakis V., Bertsias G., Lamprou V. Quality of life before and after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. A prospective cohort study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015 Jan-Feb;11(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Su Bin, Kim Seong Min. Short-term analysis of food tolerance and quality of life after laparoscopic greater curvature plication. Yonsei Med. J. 2016 Mar;57(2):430–440. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bužgová Radka, Bužga Marek, Holéczy Pavol. Health-related quality of life in morbid obesity: the impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Cent. Eur. J. Med. June 2014;9(3):374–381. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fezzi Margherita, Kolotkin Ronnette L., Nedelcu Marius, Jaussent Audrey, Roxane Improvement in quality of life after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. August 2011;21(8):1161–1167. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bužgová Radka, Bužga Marek, Holéczy Pavol, et al.,Bariatric Evaluation of Quality of Life, Clinical Parameters, and Psychological Distress After Bariatric Surgery: Comparison of the Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Laparoscopic Greater Curvature Plication, Surgical Practice and Patient Care.

- 24.Oh Sung-Hee, Song Hyun Jin, Kwon Jin-Won. The improvement of quality of life in patients treated with bariatric surgery in Korea. J. Kor. Surg. Soc. 2013 Mar;84(3):131–139. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.84.3.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams T.D. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(8):753–761. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitcomb Emily L., Horgan Santiago, Donohue Michael C. Impact of surgically induced weight loss on pelvic floor disorders. Int. Urogynecol. J. August 2012;23(8):1111–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King W.C. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516–2525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann Ingrid Borba, Fries Gabriel Rodrigo, Bücker Joana. The FKBP5 polymorphism rs1360780 is associated with lower weight loss after bariatric surgery: 26 months of follow-up. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016;12(8):1554–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterli Ralph, Borbély Yves, Kern Beatrice. Early Results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Ann. Surg. November 2013;258(5):690–695. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a67426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunault Paul. Observations regarding ‘quality of life’ and ‘comfort with food’ after bariatric surgery: comparison between laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. August 2011;21:1225. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann Andrzej. Comparison of percentage excess weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Videosurg. Miniinv. 2014;9(3):351–356. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.44257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee Y.C., Lee C.K., Liew P.L. Evaluation of quality of life and impact of personality in Chinese obese patients following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2011;58(109):1248–1251. doi: 10.5754/hge10619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin D.J. Predictors of weight loss 2 years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2015 Aug;8(3):328–332. doi: 10.1111/ases.12193. Epub 2015 Apr 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjöström L. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307(1):56–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King W.C. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516–2525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]