Abstract

Background

Since the 2012 approval of shaped implants, their use in breast reconstruction has increased in the United States. However, large-scale comparisons of complications and patient-reported outcomes are lacking. The authors endeavored to compare surgical and patient-reported outcomes across implant types.

Methods

The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium database was queried for expander/implant reconstructions with at least 1-year post-exchange follow-up (mean, 18.5 months). Outcomes of interest included postoperative complications, 1-year revisions, and patient-reported outcomes. Bivariate and mixed-effects regression analyses evaluated the effect of implant type on patient outcomes.

Results

Overall, 822 patients (73.5 percent) received round and 297 patients (26.5 percent) received shaped implants. Patients undergoing unilateral reconstructions with round implants underwent more contralateral symmetry procedures, including augmentations (round, 18.7 percent; shaped, 6.8 percent; p = 0.003) and reductions (round, 32.2 percent; shaped, 20.5 percent; p = 0.019). Shaped implants were associated with higher rates of infection (shaped, 6.1 percent; round, 2.3 percent; p = 0.002), that remained significant after multivariable adjustment. Other complication rates did not differ significantly between cohorts. Round and shaped implants experienced similar 2-year patient-reported outcome scores.

Conclusions

This prospective, multicenter study is the largest evaluating outcomes of shaped versus round implants in breast reconstruction. Although recipients of round implants demonstrated lower infection rates compared with shaped implants, these patients were more likely to undergo contralateral symmetry procedures. Both implant types yielded comparable patient-reported outcome scores. With appropriate patient selection, both shaped and round implants can provide acceptable outcomes in breast reconstruction.

Clinical Question/Level of Evidence

Therapeutic, III.

Since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's approval of anatomical implants in 2012,1 there has been increasing adoption of this new technology for breast reconstruction in the United States.2–4 Reported benefits of shaped implants include superior lower pole projection and upper pole fill—both features of a more “natural teardrop” appearance.5,6 Rupture data from U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European studies also suggest potential improvement in rupture rates, compared with less cohesive gel implants.7–9 In theory, the textured surfacing of shaped implants may produce lower capsular contracture rates compared with the pre-existing standard of smooth round implants.10,11 These advantages must be weighed against potential problems with firmness, malposition, and malrotation.

Although previous studies have compared outcomes of these two distinct classes of implants in aesthetic breast surgery, few investigators have examined the utility of shaped implants in breast reconstruction.6,7,9,12–17 Indeed, the advantages of shaped implants may be greater in breast reconstruction, given the relative paucity of soft-tissue coverage in most mastectomy skin flaps. Compared with breast augmentation, reconstruction presents greater risks of upper pole hollowing and contour rippling. Moreover, with the skin deficits imposed by mastectomy, creation of adequate lower pole projection and maintenance of a natural breast shape present significant additional challenges.18 With the potential advantages of shaped over smooth round implants, it also remains uncertain whether implant choice impacts the need for contralateral symmetry procedures or subsequent revision procedures.

Use of shaped implants in reconstruction may have potential disadvantages as well. Unlike augmentation, in which the glandular structures remain intact, the relatively greater dead space in the postmastectomy breast may pose a higher risk for implant malposition. With the loss of soft tissue beneath mastectomy skin flaps, the relative firmness and immobility of shaped, textured implants may be additional disadvantages.19,20 The texturing of shaped devices may promote biofilm adherence, which may be associated with infection and contracture.21,22

Because the relative benefits and risks of shaped implants over round devices have not been well studied in mastectomy reconstruction, new research is needed to evaluate clinical and patient-reported outcomes in this patient populations. Given the increased promotion—and use—of shaped implants, we endeavored to evaluate the effects of implant type on outcomes using a multi-institutional, prospective analysis of breast reconstruction.

Patients and Methods

The patients included in this analysis were recruited as a part of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study, a 5-year prospective, multicenter cohort study of mastectomy reconstruction patients, funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI 1RO1CA152192). Beginning in February of 2012, women aged 18 years or older, undergoing first-time immediate or delayed breast reconstruction following skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, were eligible for inclusion. Reconstructive procedure choice was based on patient and surgeon preferences. The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study collectively included 57 participating plastic surgeons from 11 centers in Michigan, New York, Illinois, Ohio, Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., Georgia, Texas, British Columbia, and Manitoba.

The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium database was queried retrospectively for all patients who (1) underwent immediate or delayed breast reconstruction using tissue-expander/implant techniques, (2) were past their 24-month postreconstruction assessment time, and (3) had at least 1-year of follow-up after expander-to-implant exchange. One thousand one-hundred nineteen cases were identified. The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study was conducted with appropriate approval from all participating sites' institutional review boards.

Outcomes Variables and Independent Variables

Outcomes of interest included complication rates, operative revisions, and subscale scores from a panel of patient-reported outcomes administered preoperatively and at 24 months postoperatively. Survey instruments included the BREAST-Q23 and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-BR23.24

Complication and revision data were collected from electronic medical records at each participating site. Only complications and revision procedures occurring after expander-to-implant exchange and within 24 months of reconstruction were included in this analysis.

The primary predictor variable in the analysis was implant shape. Other independent variables included demographics such as patient age and body mass index. Medical comorbidities were scored by means of the Charlson index.25 In addition, data were gathered on clinical variables such as implant material and volume, laterality, indications for mastectomy (i.e., therapeutic or prophylactic), lymph node management, use of acellular dermal matrix, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. For the comparison of both complications and patient-reported outcomes, the analyses also controlled for a patient's duration of follow-up (i.e., the number of months between expander exchange and 24 months).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for relevant baseline characteristics were calculated for the shaped and round implant cohorts. Bivariate analyses, including Pearson's chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables, identified significant differences in baseline characteristics between the cohorts. Unadjusted comparisons of complication rates and patient-reported outcomes between the two cohorts were made using logistic and linear regression models, respectively, with implant shape as a single predictor. For both logistic and linear regressions, mixed-effects models with sites as random intercepts were used to adjust for potential within-site correlation of outcomes. For covariate-adjusted comparisons of complications and patient-reported outcomes at 2 years, the respective regression models were adjusted for baseline characteristics that were potential confounders or known to be associated with the outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.), and statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

In total, 1119 patients met our inclusion criteria, including 822 (73.5 percent) who underwent breast reconstruction with round implants and 297 (26.5 percent) who underwent breast reconstruction with shaped implants. Demographic and clinical variables, and bivariate analyses, are summarized in Table 1. Differences between the study cohorts were observed for a number of the variables, with patients with round implants having a higher body mass index (p = 0.004) and lower Charlson index (p = 0.032) than patients receiving shaped implants. Moreover, patients with round implants were significantly more likely to have mastectomies for prophylaxis (p = 0.040) and use acellular dermal matrix (p < 0.001). In contrast, the shaped implant cohort had a higher likelihood of having had radiation therapy (p = 0.002) compared with women who received round implants. A significantly higher mean volume was observed for the round implant cohort, compared with that of the shaped implant group (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Overall (N = 1119) and by Shape of Implant.

| Characteristics | Overall | Implant Shape | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Round (%) | Shaped (%) | |||

| No. of patients | 1119 | 822 (73.5) | 297 (26.5) | |

| Mean age ± SD, yr | 48.0 ± 10.3 | 48.2 ± 10.4 | 47.5 ± 10.0 | 0.270 |

| Mean BMI ± SD, kg/m2 | 25.2 ± 5.0 | 25.5 ± 5.3 | 24.5 ± 4.2 | 0.004 |

| Mean implant volume ± SD, ml | 500 ± 150 | 520 ± 150 | 450 ± 140 | <0.0001 |

| Mean length of follow-up ± SD, mo* | 18.5 ± 2.3 | 18.5 ± 2.3 | 18.3 ± 2.4 | 0.312 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Unilateral | 390 (34.9) | 273 (33.2) | 117 (39.4) | |

| Bilateral | 729 (65.1) | 549 (66.8) | 180 (60.6) | 0.055 |

| Indication for mastectomy | ||||

| Therapeutic | 988 (88.3) | 716 (87.1) | 272 (91.6) | |

| Prophylactic | 131 (11.7) | 106 (12.9) | 25 (8.4) | 0.040 |

| Lymph node biopsy | ||||

| None | 224 (20.0) | 188 (22.9) | 36 (12.1) | |

| SLNB | 580 (51.8) | 421 (51.2) | 159 (53.5) | |

| ALND | 315 (28.2) | 213 (25.9) | 102 (34.3) | 0.000 |

| Mastectomy type | ||||

| Nipple-sparing | 207 (18.5) | 154 (18.7) | 53 (17.8) | |

| Simple or modified radical | 906 (81.0) | 664 (80.8) | 242 (81.5) | |

| Mixed | 6 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | 0.883 |

| ADM used | 570 (50.9) | 449 (54.6) | 121 (40.7) | 0.000 |

| Implant material | ||||

| Silicone | 983 (87.8) | 723 (88.0) | 260 (87.5) | |

| Saline | 136 (12.2) | 99 (12.0) | 37 (12.5) | 0.852 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 752 (67.9) | 557 (68.3) | 195 (67.0) | |

| Previous smoker | 329 (29.7) | 239 (29.3) | 90 (30.9) | |

| Current smoker | 26 (2.3) | 20 (2.5) | 6 (2.1) | 0.826 |

| Comorbidity (Charlson index) | ||||

| 0 | 98 (8.8) | 80 (9.7) | 18 (6.1) | |

| 1 | 927 (82.8) | 681 (82.8) | 246 (82.8) | |

| ≥2 | 94 (8.4) | 61 (7.4) | 33 (11.1) | 0.032 |

| Radiation therapy | ||||

| Premastectomy | 54 (4.8) | 36 (4.4) | 18 (6.1) | |

| Postmastectomy | 143 (12.8) | 89 (10.8) | 54 (18.2) | |

| None | 922 (82.4) | 697 (84.8) | 225 (75.8) | 0.002 |

| Chemotherapy during/after reconstruction | 320 (28.6) | 222 (27.0) | 98 (33.0) | 0.050 |

BMI, body mass index; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; ADM, acellular dermal matrix.

Defined as the duration between tissue expander–to-implant exchange and 1 year after initial surgery.

Revisions and Symmetry Procedures

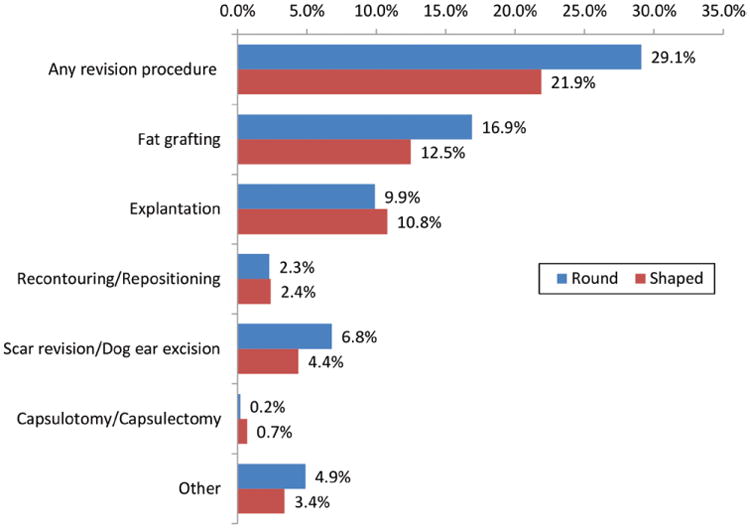

Revision rates are summarized in Figure 1. At a mean 18.5 months' follow-up, 29.1 percent of the round implant cohort had undergone operative revisions compared with 21.9 percent of the shaped implant cohort (p = 0.129). The most common individual revision procedures were fat grafting (round, 16.9 percent; shaped, 12.5 percent; p = 0.097) and explantation (round, 9.9 percent; shaped, 10.8 percent; p = 0.365). Capsulotomy/capsulectomy, recontouring/repositioning, and scar revision/dog-ear excision rates did not differ significantly between cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Surgical revision rates with shaped and round implants. The p value is based on mixed-effects logistic regression analyses adjusting for variations across participating hospitals. P values were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Mean follow-up is 18.5 months, with a minimum of 12 months after expander-to-implant exchange.

Analysis of contralateral symmetry procedures in 390 patients with unilateral reconstructions (Table 2) showed the round implant cohort to be more likely than the shaped implant cohort to receive a contralateral breast reduction (round, 18.7 percent; shaped, 6.8 percent; p = 0.003) or augmentation (round, 32.2 percent; shaped, 20.5 percent; p = 0.019).

Table 2. Contralateral Procedure by Implant Shape*.

| Round (%) | Shaped (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 273 | 117 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Mastopexy | 92 (33.7) | 33 (28.2) | 0.287 |

| Reduction | 51 (18.7) | 8 (6.8) | 0.003 |

| Augmentation | 88 (32.2) | 24 (20.5) | 0.019 |

| Other | 13 (4.8) | 7 (6.0) | 0.616 |

Only unilateral patients were included.

Complications

Bivariate analysis results are summarized in Table 3. Overall, 5.5 percent of the round and 9.8 percent of the shaped implant cohorts experienced a postoperative complication (p = 0.008), of which 3 percent and 8.1 percent, respectively (p = 0.001), were major complications, and 1 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively (p = 0.005), resulted in failure. The most common complication was surgical-site infection (shaped, 6.1 percent; round, 2.3 percent; p = 0.002). Although rates of surgical-site infection requiring oral antibiotics or surgical intervention did not differ between cohorts, shaped implants were more likely to have infections requiring intravenous antibiotics than round implants (p = 0.001). Rates for other complications, including seroma, hematoma, mastectomy flap necrosis, implant malposition, capsular contracture, and implant rupture, did not differ significantly between cohorts. Regression analyses (Table 4) identified shaped implant to be an independent risk factor for any complication (OR, 1.83) and major complications (OR, 2.81).

Table 3. Postoperative Complication* Rate by Shape of Implant.

| Round (%) | Shaped (%) | p† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 822 | 297 | |

| Complication | |||

| Any complication | 45 (5.5) | 29 (9.8) | 0.008 |

| Major complication | 25 (3) | 24 (8.1) | 0.001 |

| Wound infection | 19 (2.3) | 18 (6.1) | 0.002 |

| Reconstructive failure | 8 (1) | 10 (3.4) | 0.005 |

| Hematoma | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0.578 |

| Wound dehiscence | 5 (0.6) | 3 (1) | 0.444 |

| Wound infection requiring oral antibiotics | 19 (2.3) | 9 (3) | 0.374 |

| Wound infection requiring IV antibiotics | 1 (0.1) | 12 (4) | 0.001 |

| Wound infection requiring surgical or percutaneous drainage of abscess | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0.755 |

| Mastectomy skin flap necrosis | 0 | 0 | |

| Capsular contracture | 9 (1.1) | 7 (2.4) | 0.289 |

| Implant malposition | 5 (0.6) | 4 (1.4) | 0.132 |

| Seroma | 8 (1) | 2 (0.7) | 0.640 |

| Implant leakage, rupture, or deflation | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.570 |

IV, intravenous.

Included those that occurred after expander-to-implant exchange only.

Based on mixed-effects logistic regression adjusting for sites (hospitals) or Fisher's exact test.

Table 4. Summary of Adjusted Odds Ratios of Implant Shape (with Round being the Reference Group) from Complication and Revision Procedure Model*.

| Outcome | Adjusted OR (Shaped vs. Round) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any complication | 1.83 | 1.05–3.19 | 0.032 |

| Major complication | 2.81 | 1.46–5.39 | 0.002 |

| Surgical-site infection | 2.71 | 1.30–5.65 | 0.008 |

| Any revision procedure | 0.89 | 0.62–1.26 | 0.494 |

| Fat grafting | 0.84 | 0.54–1.29 | 0.427 |

Each model included as covariates age, body mass index, implant volume, length of follow-up, implant shape, implant material, laterality, indication for mastectomy, lymph node biopsy, acellular dermal matrix use, smoking status, comorbidity, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy; also included are random intercepts for study sites (hospitals).

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Baseline and 2-year postoperative patient-reported outcome scores for the BREAST-Q and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-BR23 are presented in Table 5. Survey data were available for 1087 patients, including 803 with round and 284 with shaped implants. In the multivariate regressions, implant shape had no significant effects on any of the BREAST-Q or European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-BR23 subscales (Table 6).

Table 5. Patient-Reported Outcomes by Round (n = 803) and Shaped (n = 284) Preoperatively and 2 Years Postoperatively.

| PROMs | Preoperatively | 2 Years Postoperatively | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| No. | Mean ± SD | No. | Mean ± SD | |

| Breast-Q Satisfaction with Breasts | ||||

| Round | 798 | 62.8 ± 21.9 | 497 | 64.6 ± 17.9 |

| Shaped | 283 | 66.1 ± 21.2 | 160 | 62.6 ± 15.7 |

| Breast-Q Psychosocial Well-being | ||||

| Round | 797 | 71.1 ± 17.8 | 492 | 74.8 ± 19.1 |

| Shaped | 282 | 73.9 ± 16.6 | 159 | 74.1 ± 18.8 |

| Breast-Q Physical Well-being | ||||

| Round | 797 | 79.3 ± 14.5 | 488 | 77.1 ± 14 |

| Shaped | 283 | 82.9 ± 13 | 159 | 78.4 ± 14.1 |

| Breast-Q Sexual Well-being | ||||

| Round | 772 | 57.9 ± 19.1 | 472 | 54.2 ± 21.3 |

| Shaped | 281 | 61.1 ± 16.6 | 156 | 53.6 ± 20.5 |

| Breast-Q Satisfaction with Outcome | ||||

| Round | — | — | 493 | 70.2 ± 21.4 |

| Shaped | — | — | 159 | 69.7 ± 21.5 |

| EORTC Body image | ||||

| Round | 793 | 81 ± 22 | 479 | 76.2 ± 25.2 |

| Shaped | 279 | 82.5 ± 21.5 | 156 | 75.4 ± 24.6 |

| EORTC Sexual function | ||||

| Round | 788 | 32.7 ± 24.5 | 474 | 32.8 ± 25 |

| Shaped | 282 | 35.3 ± 25.2 | 156 | 34 ± 24.2 |

| EORTC Sexual enjoyment | ||||

| Round | 541 | 63.3 ± 27.2 | 295 | 58.8 ± 26.2 |

| Shaped | 203 | 65.2 ± 28 | 101 | 61.4 ± 29.3 |

PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

No. of patients with complete patient-reported outcomes.

Table 6. Summary of Patient-Reported Outcome Regression Coefficients for Implant Shape*.

| Outcome | Coefficient (Shaped vs. Round) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BREAST-Q: | |||

| Satisfaction with Breasts | −0.67 | −4.26–2.49 | 0.678 |

| Psychosocial Well-being | −1.80 | −5.10–1.50 | 0.285 |

| Physical Well-being | −0.18 | −2.65–2.29 | 0.886 |

| Sexual Well-being | −2.49 | −6.27–1.29 | 0.196 |

| Satisfaction with Outcome | 1.87 | −2.14–5.88 | 0.360 |

| EORTC | |||

| Body image | −2.23 | −6.78–2.32 | 0.337 |

| Sexual function | 0.58 | −3.53–5.69 | 0.782 |

EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Coefficients represent adjusted mean difference in 1-year outcome between round and shaped, with round being the reference group. Each model included as covariates baseline outcome (except for BREAST-Q Satisfaction with Outcome), age, body mass index, implant volume, length of follow-up, implant shape, implant material, laterality, indication for mastectomy, lymph node biopsy, acellular dermal matrix use, smoking status, comorbidity, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Also included are random intercepts for study sites (hospitals); Results were weighted by the inverse of predicted response probability of patient-reported outcome measures at postoperative year 1.

Discussion

In recent years, implant choices have evolved to include both shaped and round forms. Despite widespread use of implant-based breast reconstruction, few direct comparisons of implant types exist. Longitudinal postmarket studies from implant manufacturers have outlined complication rates such as reoperation, explantation, and infection; however, in-depth assessments of risk factors and comorbidities are often not performed in these analyses.15 Other well-designed studies that have compared patient-reported outcomes between shaped and round implants have been limited by small sample sizes.7 The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study is well suited to perform analyses of different implant types because of its prospective, multicenter design, and its inclusion of risk factors, surgical outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes.

In our analysis, demographic and clinical differences existed between the two cohorts (Table 1)—most notably, with a higher percentage of shaped implants having associated radiation therapy. Given that radiation creates tighter, thinner mastectomy flaps, shaped implants—by virtue of their firmer, more projecting design and improved structural reach into the upper pole—may provide an advantage over their round, softer gel counterparts. The increased use of shaped implants in these patients may reflect this putative benefit. Furthermore, the finding that the round implant cohort had a higher body mass index and greater implant volume may be an artifact of the limited availability of higher volume shaped implants.

With the exception of surgical-site infection requiring intravenous antibiotics, individual complication rates did not differ significantly between the shaped and round implant cohorts. Although our infection rates are generally low and in alignment with the literature, the rate of infections requiring intravenous antibiotics was higher within the shaped cohort (4.0 percent) compared with the round cohort (0.1 percent; p = 0.001). This difference is potentially attributable to the higher rates of postmastectomy irradiation in the shaped implant cohort (Table 1), but further multivariable analyses adjusting for radiation therapy and other baseline covariates could not be performed because of the small number of infections requiring intravenous antibiotics. The incidences of other early complications such as seroma, hematoma, wound dehiscence, and explantation were similar in the two groups. Our follow-up, however, is insufficient to fully address late complications such as implant malposition, rupture, and capsular contracture. Although the low rates of these complications in this series are consistent with other short-term reports in the literature, previous manufacturer data show an increase in the malposition rate to 5 to 6 percent at 8 to 10 years.5,6,12 Additional studies will be necessary to bear out any significant impact of implant shape on these outcomes. The variation in surgical-site infection rates between our cohorts appears to drive the overall difference observed in major and overall complication rates. Mixed-effects logistic regression models confirmed these differences between the two cohorts after controlling for potential confounding. Although the underlying causes for these differences are uncertain, they may be attributable to the textured surfacing of shaped implants, with the potential for greater bacterial adherence and subsequent biofilm formation.21,22

Unilateral reconstructions with round implants underwent more contralateral symmetry procedures, including augmentation (round, 32.2 percent; shaped, 20.5 percent; p = 0.019) and reduction (round, 18.7 percent; shaped, 6.8 percent; p = 0.003) for symmetry (Table 2). The benefit of shaped implants may be in their more natural shape, and this may account for the decreased need for contralateral symmetry procedures.

In our study population, roughly one in four patients underwent revision of their breast reconstruction (Fig. 1). Although lower than the 45 to 55 percent long-term revision rates noted in core studies of longer duration,5,6,12,26 these results are consistent with other 1- and 2-year analyses.6 Although not statistically significant, higher rates of revision procedures were seen with round versus shaped implants (29.1 percent versus 21.9 percent, respectively; p = 0.129)—attributable largely to higher use of fat grafting. Two common indications for fat grafting in prosthetic breast reconstruction are upper pole hollowing and rippling.7,27,28 Because shaped implants have a structural extension into the upper pole, resulting in a less abrupt transition, and are less prone to rippling because of their firmer composition, patients with this type of implant may require fat grafting less frequently.

With over 1100 patients, our analysis is the largest to date to compare patient-reported outcomes between shaped and round implants. Moreover, the response rate to the patient-reported outcome surveys was generally robust at 65 percent—above the 60 percent threshold generally agreed on as acceptable for clinical research.29–31 Overall, patient-reported outcome scores did not differ between the implant types, which is congruent with earlier, smaller comparative studies.7 However, patients in the shaped implant cohort reported higher well-being and satisfaction scores before surgery.

As always, there were limitations to our study. Because implant selection was nonrandom, preexisting patient or surgeon factors may have accounted for cohort differences (or lack thereof). For example, the two cohorts may not have differed with regard to satisfaction simply because each patient received the implant that specifically suited their clinical presentation. Without a randomized design, there was a potential for selection bias—patients with greater tightness or contour deformity may have been preferentially selected for shaped implants, to improve lower pole projection and overall contour. Moreover, the effects of implant type on patient-reported outcomes may have been confounded by revision procedures. The impact of surgeon experience and steeper learning curves with the newer shaped implant technology could also have produced differences in complication rates between the implant types. For the complications that typically manifest at later time points—contracture and rupture—our follow-up period is not sufficient to evaluate real differences. Although use of a randomized clinical trial design would have addressed many of these potential limitations, this approach would be logistically difficult, given the strong surgeon and patient preferences inherent in clinical decision-making for breast reconstruction.

Conclusions

There is a paucity of research investigating the impact of implant types on breast reconstruction outcomes. This prospective, multicenter analysis is the largest to date evaluating outcomes of round versus shaped implants. In our analysis, round implants were associated with lower rates of infection compared with shaped devices. However, shaped implants appeared to require fewer contralateral symmetry procedures than their round counterparts. Ultimately, both devices yielded comparable patient-reported satisfaction at 2 years after reconstruction. With appropriate patient selection, both implant types can provide acceptable outcomes for breast reconstruction patients.

Acknowledgments

The Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI 1RO1CA152192).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Kim and Dr. Clemens are past advisory board members of Allergan. All other authors have no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Re: P040046 Natrelle 410 highly cohesive anatomically shaped silicone-filled breast implant. [Accessed July 17, 2016]; Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf4/p040046a.pdf.

- 2.O'Shaughnessy K. Evolution and update on current devices for prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2015;4:97–110. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.03.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel A, Maxwell GP. The evolution of breast implants. Clin Plast Surg. 2015;42:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calobrace MB, Capizzi PJ. The biology and evolution of cohesive gel and shaped implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(Suppl):6S–11S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell GP, Van Natta BW, Bengtson BP, Murphy DK. Ten-year results from the Natrelle 410 anatomical form-stable silicone breast implant core study. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:145–155. doi: 10.1093/asj/sju084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens WG, Harrington J, Alizadeh K, Broadway D, Zeidler K, Godinez TB. Eight-year follow-up data from the U.S. clinical trial for Sientra's FDA-approved round and shaped implants with high-strength cohesive silicone gel. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macadam SA, Ho AL, Lennox PA, Pusic AL. Patient-reported satisfaction and health-related quality of life following breast reconstruction: A comparison of shaped cohesive gel and round cohesive gel implant recipients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:431–441. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31827c6d55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MH, Shenker R, Silver SA. Cohesive silicone gel breast implants in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:768–779. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000176259.66948.e7. discussion 780–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell GP, Van Natta BW, Murphy DK, Slicton A, Bengtson BP. Natrelle style 410 form-stable silicone breast implants: Core study results at 6 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32:709–717. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12452423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramo AC, De Oliveira VR, Ledo-Silva MC, De Oliveira EL. How texture-inducing contraction vectors affect the fibrous capsule shrinkage around breasts implants? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34:555–560. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens WG, Nahabedian MY, Calobrace MB, et al. Risk factor analysis for capsular contracture: A 5-year Sientra study analysis using round, smooth, and textured implants for breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1115–1123. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000435317.76381.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond DC, Migliori MM, Caplin DA, Garcia ME, Phillips CA. Mentor Contour Profile Gel implants: Clinical outcomes at 6 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1381–1391. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824ecbf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham B, McCue J. Safety and effectiveness of Mentor's MemoryGel implants at 6 years. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:440–444. doi: 10.1007/s00266-009-9364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spear SL, Murphy DK, Slicton A, Walker PS Inamed Silicone Breast Implant U.S. Study Group. Inamed silicone breast implant core study results at 6 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(Suppl 1):8S–16S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000286580.93214.df. discussion 17S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caplin DA. Indications for the use of MemoryShape breast implants in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery: Long-term clinical outcomes of shaped versus round silicone breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(Suppl):27S–37S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahabedian MY. Shaped versus round implants for breast reconstruction: Indications and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:e116. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens WG, Harrington J, Alizadeh K, et al. Five-year follow-up data from the U.S. clinical trial for Sientra's U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved Silimed brand round and shaped implants with high-strength silicone gel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:973–981. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826b7d2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chopp D, Rawlani V, Ellis M, et al. A geometric analysis of mastectomy incisions: Optimizing intraoperative breast volume. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:45–50. doi: 10.1177/229255031101900201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tebbetts JB. Form stability of the style 410 implant: Definitions, conjectures, and the rest of the story. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:825–826. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822216f0. author reply 826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calobrace MB. The design and engineering of the MemoryShape breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(Suppl):10S–15S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacombs A, Tahir S, Hu H, et al. In vitro and in vivo investigation of the influence of implant surface on the formation of bacterial biofilm in mammary implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:471e–480e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamboto H, Vickery K, Deva AK. Subclinical (biofilm) infection causes capsular contracture in a porcine model following augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:835–842. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: First results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2756–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, Jani AB, Vijayakumar S. An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spear SL, Murphy DK Allergan Silicone Breast Implant U.S. Core Clinical Study Group. Natrelle round silicone breast implants: Core Study results at 10 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1354–1361. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn TT, Miller GS, Rostek M, Cabalag MS, Rozen WM, Hunter-Smith DJ. Prosthetic breast reconstruction: Indications and update. Gland Surg. 2016;5:174–186. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.07.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HY, Jung BK, Lew DH, Lee DW. Autologous fat graft in the reconstructed breast: Fat absorption rate and safety based on sonographic identification. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41:740–747. doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.6.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badger F, Werrett J. Room for improvement? Reporting response rates and recruitment in nursing research in the past decade. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macadam SA, Zhong T, Weichman K, et al. Quality of life and patient-reported outcomes in breast cancer survivors: A multi-center comparison of four abdominally-based autologous reconstruction methods. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(Suppl):86–87. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000479932.11170.8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]