Abstract

Patient-identified barriers to immunosuppressive medications are associated with poor adherence and negative clinical outcomes in transplant patients. Assessment of adherence barriers is not part of routine post-transplant care, and studies regarding implementing such a process in a reliable way are lacking. Using the Model for Improvement and PDSA cycles, we implemented a system to identify adherence barriers, including patient-centered design of a barriers assessment tool, identification of eligible patients, clear roles for clinic staff, and creating a culture of non-judgmental discussion around adherence. We performed time-series analysis of our process measure. Secondary analyses examined the endorsement and concordance of adherence barriers between patient-caregiver dyads. After three methods of testing, the most reliable delivery system was an EHR-integrated tablet that alerted staff of patient eligibility for assessment. Barriers were endorsed by 35% of caregivers (n=85) and 43% of patients (n=60). The most frequently patient-endorsed barriers were forgetting, poor taste, and side effects. Caregivers endorsed forgetting and side effects. Concordance between patient-caregiver dyads was fair (k=0.299). Standardized adherence barriers assessment is feasible in the clinical care of pediatric kidney transplant patients. Features necessary for success included automation, redundant systems with designated staff to identify and mitigate failures, aligned reporting structures, and reliable measurement approaches. Future studies will examine whether barriers predict clinical outcomes (eg, organ rejection, graft loss).

Keywords: child, nephrology, patient compliance, quality improvement, transplants

1 | INTRODUCTION

Child and young adult kidney transplant recipients have poor allograft survival rates compared to older adults, with up to 30% of allografts failing by 5 years.1 Graft failure risk increases substantially during the transition from childhood to adolescence and peaks at 19 years of age, when the risk of allograft loss is nearly three times that of younger children and older adults.2 This has profound negative consequences on patient health and quality of life, and the larger healthcare system. Life expectancy decreases by 27–37 years,1 and quality of life diminishes3 for children or adolescents who need dialysis due to kidney failure despite care that costs up to four times as much.1 Up to 43% of adolescents are non-adherent to their immunosuppression regimen, which accounts for 23% of late acute rejection episodes and 44% of graft losses.4 Notably, even a 10% improvement in adherence can lead to an 8% reduction in graft failure.5 An important first step to improving adherence behaviors is identifying barriers to adherence encountered by children and young adults who have undergone kidney transplantation. As described in several models (eg, Pediatric Self-management Model,6 WHO model of adherence,7 Health Belief Model8), barriers can be individual, family, healthcare system, or community-level factors that interfere with adherence to the medical regimen. For example, individual barriers may include forgetting to take medications, difficulty swallowing pills, refusal, and side effects, while family barriers include running out of medication, health literacy, and inability to afford the medication. Similarly, barriers in the healthcare system, which are critical for the current study, include poor physician-patient communication around the treatment regimen and prescribed regimens being too complex and difficult to understand. Thus, targeting these barriers is critical for improving adherence behaviors.9,10

Research demonstrates that patient-identified adherence barriers are tightly linked with adherence across chronic conditions.11,12 In solid organ transplantation, barriers such as being embarrassed to take pills in front of others, feeling like there are too many pills or side effects, and forgetting to take medications are linked to important adverse clinical outcomes, such as rejection, hospitalization, and death.10 Despite these data, there is little research regarding the implementation of systematic assessment of adherence barriers in clinical practice.

The goal of this project was to standardize adherence barriers assessment using a new barriers checklist based on the larger pediatric adherence literature9,11,13–16 and integrate screening into clinical practice. Our objective was to develop a process to systematically assess for barriers to taking immunosuppression medications for patients who have undergone kidney transplantation as well as their caregivers as a part of routine clinical care. This included developing a BAT and testing various methods of delivering the tool to patients seen in clinic in a reliable manner. A secondary objective was to report the most frequently reported barriers and whether there was agreement between the patients and their caregivers. We have reported our process according to the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines.17

2 | METHODS

2.1 | Context

Our multidisciplinary team consists of nine pediatric nephrologists, eight clinical fellows, seven nurses, three nurse transplant coordinators, two registered dietitians, one social worker, and one advanced practice nurse. We perform approximately 25 transplants annually and follow just over 100 kidney transplant patients across six outpatient clinic locations. On average, 12–18 kidney transplant patients are seen by a nephrologist or nurse practitioner each week. Immediately after discharge from kidney transplantation, patients are followed up to twice weekly. The visit frequency is spaced out over the first year, and stable patients are seen at least every 3 months. Once they have arrived to clinic, patients are checked in by central registration staff, then taken to an examination room, where vitals and history are recorded by a medical assistant or nurse. The patient, with their caregiver when present, is evaluated by the nurse practitioner or nephrologist. The patient may also see a registered dietitian or social worker during the visit. Finally, the nurse discharges the patient when the visit is complete. Prior to beginning this project, there was no formal process to identify and document adherence barriers. This work was part of a quality improvement initiative, and as such deemed exempt from full review by the site’s institutional review board, with a waiver of consent.

2.2 | Interventions

2.2.1 | Key drivers

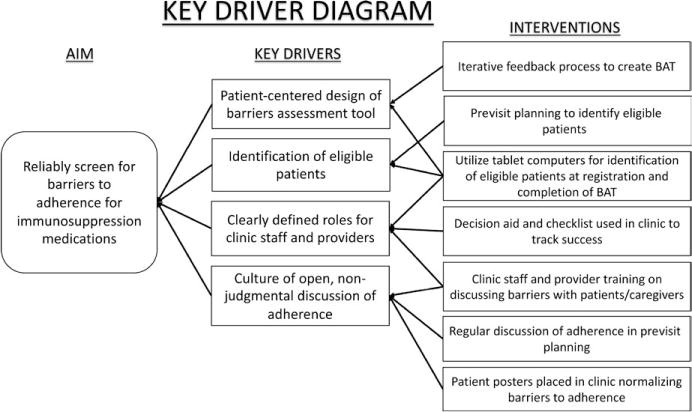

A multidisciplinary team consisting of a patient, nephrology fellow, quality improvement consultants, advanced practice nurse, nurse transplant coordinators, social worker, pharmacist, clinic nurse, adherence psychologists, data analyst, and nephrologist was formed with the goal to create, test, and implement a system to assess and improve medication adherence for solid organ transplant recipients. The team met for 60 minutes each week for planning and development of the system. A necessary early step was to identify the essential factors or “key drivers” (Figure 1) required to reliably identify eligible kidney transplant recipients and screen them for barriers to taking their immunosuppression medications during their clinic visit. The key drivers are the theoretical model for change that are then tested with PDSA cycles, as described by the Model for Improvement,18 and were developed by group consensus in the first two weekly meetings. Consensus was determined when all team members were in agreement. PDSA cycles testing interventions that addressed our key drivers were tracked using statistical process control charts.19 We utilized “Pareto” charts,20 which are used to identify the most common failure modes to focus interventions where they are most needed, and developed interventions to address these failure modes.

FIGURE 1.

Key driver diagram for reliable assessment of barriers to adherence

Patient-centered design of the BAT

We created an empirically based questionnaire to screen patients and their caregivers for barriers to taking immunosuppression medications. The design of the BAT was based on prior work in other pediatric subspecialties, including items on 5-point Likert scales that are used for research purposes.9,11,13–16 As these tools are too lengthy for clinical practice, a new tool was developed that could be quickly and easily administered and scored in a clinical setting. The BAT contains 14 commonly endorsed barriers with a checkbox next to each item. The types of barriers include logistical issues (eg, forgetting, inconvenience), ingestion difficulties (eg, swallowing, taste), efficacy (eg, feel I don’t need it), financial difficulties, regimen characteristics (eg, too many medications, side effects), and patient-specific issues (eg, refusal by child, embarrassment). We modified the BAT using an iterative process incorporating feedback from patients and their caregivers, healthcare providers, and patient education specialists. Specific feedback received from patients included simplifying the wording, using a checklist format, and removing double meaning items. The BAT was used as self-report tool. While we did not test it in interview format, it could be used in that manner as determined for specific patient needs (eg, poor vision, or for patients that cannot read). The BAT may be obtained from the corresponding senior author upon request to interested individuals.

Identification of eligible patients

We addressed our first key driver to reliably identify patients eligible for barriers assessment. We initially targeted children 10 years of age and older who were one year post-transplant because this population of patients are most likely to encounter adherence barriers.9,21 Upon review of the first five patients’ completion of the BAT, our group recognized the importance of obtaining patient and caregiver perspectives to adherence barriers, regardless of patient age and time since transplant; therefore, we decided to expand the assessment to all children (and/or their caregivers) who had received a transplant to proactively identify barriers regardless of risk factors. Because caregivers and patients have unique perspectives regarding adherence barriers,11 we administered a BAT to all patients 10 years of age or older and to all caregivers (regardless of patient age) if they were present. The BAT was administered every 3–6 months. Initially, patients were identified during weekly previsit planning (ie, multidisciplinary team meeting to discuss the laboratory, psychosocial, and medical needs of patients scheduled the following week). Each patient has their own visit planning sheet to facilitate in-clinic care, which we modified to indicate when the patient had most recently completed a BAT and whether they were due for a BAT at their upcoming visit. With future tests of change, we automated the process of patient identification and BAT administration through the EHR using tablets programmed to elicit barriers according to our protocol.

Developing a reliable process to administer the BAT to patients and deliver results to the provider in a manner that supported intervention was the most challenging step. We used successive PDSA cycles to develop such a process. The first trial relied on registration staff to provide the BAT to patients and/or their caregiver at check-in based on a list created during previsit planning. The medical assistant or nurse collected the tool at intake and gave it to the nephrologist for review. The second trial was for the medical assistant or nurse to provide the BAT to the patient and/or caregiver while in the room with the patient, then to give the completed BAT to the nephrologist for review. Our final system relies on the EHR to automatically alert registration staff at check-in to provide eligible patients with the BAT via tablet. Results are automatically transmitted from the tablet into a flowsheet within the EHR for review by the nephrologist.

Clearly defining roles for clinic staff

The clinic staff (ie, medical assistants, nurses) are instrumental for interventions to be successful. We held multiple educational sessions with the staff to elicit feedback on the PDSA cycles. Staff were empowered to troubleshoot problems as they arose at the point of care. One clinic nurse that was most often present was designated as a point-person to track successes during the clinic and mitigate failures. In addition to clinic staff managing the assessment process in clinic, the nephrologists, nurse practitioners, and transplant coordinators were trained by team members from the Division of Behavioral Medicine and Child Psychology on how to optimally discuss and provide adherence interventions based on BAT results with patients and their families. Continued training occurred as new staff joined teams and as we spread our work to our clinic locations.

Creating a culture of open, non-judgmental discussion of barriers

Some interventions focused on creating a culture that invited patients to discuss barriers. These interventions included formal training of clinic staff and providers on discussing barriers to adherence in a non-judgmental, patient-centered fashion; routine discussion of patient adherence during previsit planning; and posters placed in the clinic rooms to normalize discussions around adherence. We focused on what “gets in the way” of patients taking their medication.

2.3 | Study of interventions

We chose the Model for Improvement18 as the evidence-based framework to guide implementation of our interventions and statistical process control as our method to evaluate the implementation process.19 While many frameworks exist for quality improvement and implementation research, we chose these two methods because of their simplicity, our familiarity and experience with their use,22 and their widespread use in healthcare settings.23

2.4 | Measures

2.4.1 | Process measure

Our primary measure was the percentage of patients seen in clinic each week who were due for BAT screening (denominator) and who had completed it successfully (numerator). Success was determined if the BAT was provided to eligible patients and returned to the project coordinator. Failures included when: (i) a patient who was due for BAT screening according to our protocol did not receive it, (ii) the patient/caregiver refused to complete the BAT, or (iii) the BAT was not returned to the project coordinator or entered into the system. We reviewed all failures in a twice-monthly meeting with clinic staff to identify areas of improvement.

2.4.2 | BAT content

We assessed responses to determine the percentage of patients/caregivers that reported at least one adherence barrier and to describe the most frequently reported barriers.

2.5 | Statistical analyses

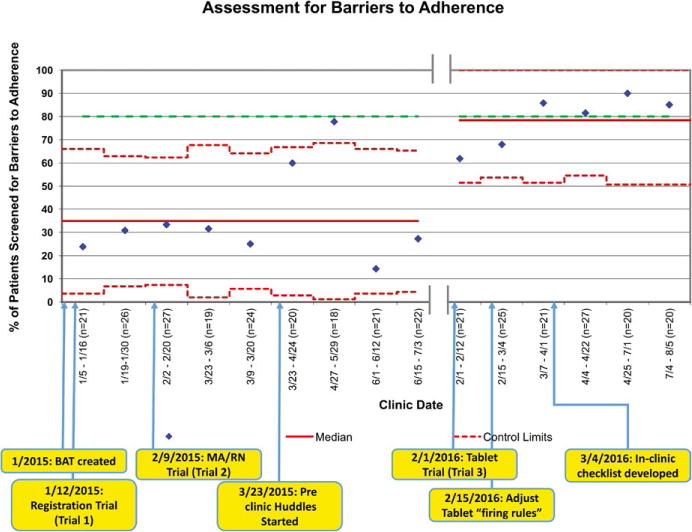

We performed a time-series analysis using statistical process control19 of our primary process measure. The percentage of eligible patients who received the BAT was plotted on a p-chart. Observations were grouped in weekly increments until approximately 20 observations were included in each data point. Data prior to automated tablet intervention (January 2015–July 2015) were compared to data following tablet implementation (February 2016–August 2016) (Figure 2). Between July 2015 and February 2016, there was a break in the process to allow for programming of the BAT onto tablets. We calculated a centerline (median) and 3-sigma (±3 standard deviation) control limits from data in the baseline period and carried them forward for comparison with the post-tablet implementation phase. Three-sigma control limits are the industry and historical standard used with statistical process control charts and have proven in practice to distinguish between common and special cause variation.24 We identified data points outside the control limits19 or consistent with other run chart rules25 as “special cause” variation indicating improvement to the system, and adjusted the centerline and control limits accordingly. We generated charts in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

FIGURE 2.

Statistical process control chart (p-chart) tracking successes in assessment for barriers to adherence. Upper and lower control limits are noted in red dotted lines with the median as a solid red line. Dates of clinics are noted along x-axis with numbers of patients represented in each data point represented by diamonds. Patients were aggregated into weekly groups until they approximated about 20 patients per data point. The various interventions described in the paper are noted on the bottom of the figure. The green dotted line is the goal line for this project

We used descriptive statistics to calculate the frequency of barriers endorsed at baseline. When BATs were completed by both the patient and their caregiver, we examined concordance using Cohen’s kappa (κ) statistic (<0.2 [slight agreement], 0.21–0.4 [fair agreement], 0.41–0.6 [moderate agreement], 0.61–0.8 [substantial agreement], >0.81 [almost perfect agreement]).26 Analyses were performed using SPSS version 23 software (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | Delivery of BAT

The success of each PDSA cycle was documented on a statistical process control chart (Figure 2). Of the three trials performed, the first method (ie, registration providing the BAT to patient/caregiver) was the least reliable. Identified challenges included the following: (i) registration staff reporting structure was not within the Division of Nephrology and had competing priorities, and (ii) non-clinical staff were unable to discuss the rationale for administering the BAT if patients/caregivers had questions or expressed hesitance.

The second trial (ie, medical assistant/nurse providing the BAT at intake) was found to be more successful. There were several factors that likely increased success of the second trial including (i) multiple education sessions during staff meetings to review the purpose of this project, (ii) the project was made a priority among nephrology leadership that supervise the clinic staff, (iii) clinic staff have more potential to form relationships with families over the course of clinic visits, and (iv) “preclinic huddles” to plan for BAT administration. The huddles are brief preclinic meetings to discuss which patients should receive a BAT during clinic, as well other potential interventions (whether they need to see a dietitian or social worker, require ambulatory blood pressure monitoring equipment, etc.). Overall, success for the second trial was variable. While there was initial improvement (>80% completion), it was not sustained over time. Investigation of failures revealed challenges including turnover of clinic staff without specific training regarding the project and overburden due to other responsibilities (running laboratories, performing intake and checking out patients, patient assessments). As a result, BAT completion was often forgotten or intentionally disregarded in light of other priorities.

The third trial (ie, automation of the BAT by triggering an alert at check-in) has been the most successful with 79% of eligible patients completing the BAT. After initial tablet system rollout, we performed iterative PDSA cycles to ensure “firing rules” for the BAT appropriately identified eligible patients. One of our clinic nurses was designated as a “champion” for the barriers assessment project. Empowered to improve assessment reliability, she created a checklist to double-check that eligible patients had received the BAT on the tablet. Ongoing failures that prevent our process from reaching 100% reliability include occasional technical issues with the tablet not firing appropriately and patient refusal. For each trial, completing the BAT required <60 seconds.

3.2 | Type and number of barriers endorsed

Barriers assessments were completed by 97 unique transplant patients and/or their caregivers (85 caregivers, 60 patients) representing 92% of our current population of 106 patients (Table 1). All patients at the time of this project were on twice-daily medication for their primary immunosuppressant (cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and/or sirolimus). For the purposes of this report, only the initial BAT responses are reported if patients completed the BAT more than once over the course of the study. Thirty-five percent of caregivers and 43% of patients endorsed at least one barrier. The most frequently endorsed barriers by caregivers included forgetting, side effects, poor taste, swallowing difficulties, running out of medicine, and child refusal while the most common barriers reported by patients were forgetting, side effects, and poor taste (Table 2). The average concordance between caregivers and patients report of each barrier (n=48) was 0.299.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics (n=97)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 13.8 (6.4), median 16, range 1–24 |

| Male gender | 51 (53) |

| Race | |

| White | 68 (70.1) |

| Black | 18 (18.6) |

| Biracial | 6 (6.2) |

| Asian | 3 (3.0) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2.1) |

| Renal diagnosis prior to transplant | |

| Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract | 46 (47.4) |

| Genetic | 22 (22.7) |

| Glomerular disease | 11 (11.3) |

| Medication-induced | 5 (5.2) |

| Vascular disease | 4 (4.1) |

| Oncologic | 2 (2.1) |

| Other | 7 (7.2) |

| Time since transplant (y) | 4.6 (5), range 0–19 |

| Type of first transplant | |

| Living-related | 58 (60) |

| Deceased | 26 (27) |

| Living-unrelated | 13 (13) |

| Kidney transplant episode | |

| First | 91 (94) |

| Second | 5 (5) |

| Third | 1 (1) |

| Primary immunosuppressant | |

| Tacrolimus | 75 (77.3) |

| Sirolimus | 18 (18.6) |

| Everolimus | 5 (5.2) |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (2.0) |

TABLE 2.

Barriers to adherence reported by patients and caregivers

| Barrier | Caregiver endorsed [n (%)] | Patient endorsed [n (%)] | Concordance (κ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forgetting | 12 (14.1) | 11 (18.3) | 0.608 |

| Side effects | 8 (9.4) | 6 (10.0) | 1.000 |

| Poor taste | 3 (3.5) | 6 (10.0) | 0.309 |

| Difficult to swallow | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.0) | 0.484 |

| Run out of medicine | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.0) | 0.657 |

| Do not want others to know I take medicine | 2 (2.4) | 3 (5.0) | 0.484 |

| Gets in the way of other activities | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.3) | 0.657 |

| Cannot afford the medicine | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| Too many medicines/too many times per day | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| Inconvenient | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| Do not think I need medicine | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.000 |

| Refuse to take medicine | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0.000 |

| Difficult to understand prescriber’s instructions | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Medicine does not work | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| Other | 1 (1.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0.000 |

4 | DISCUSSION

Using the Model for Improvement18 and iterative PDSA cycles as well as other quality improvement methods, we implemented a systematic, efficient, and reliable process to assess adherence barriers in a large pediatric kidney transplant practice. After piloting via paper and pencil, we found the most reliable way to ensure eligible patients completed the BAT was to use tablets when patients checked in for their nephrology clinic visit, coupled with staff awareness and an “Identify and Mitigate” double-check strategy in clinic. Despite utilizing an automated assessment, we found that coupling this with a system to identify and recognize failures in real time led to the most patients accurately being identified and assessed. Considering staff turnover and multiple competing priorities, it is not surprising that an automated system was more reliable than a process that was completely person-dependent. Our findings are consistent with prior studies showing that automated assessment of patient-reported health indicators can be reliable and valid.27,28

Despite a strong literature supporting the need to assess adherence barriers in kidney transplant recipients,9,10 this has not been routinely implemented in the clinical setting. The goal of this project was to take a research-based assessment of adherence barriers and incorporate it into routine clinical care. Using quality improvement methodology, we tested multiple ways to incorporate barriers screening into a busy clinic workflow. Our iterative testing of the instrument on paper and using clinical staff led to valuable learning and refinement of the assessment delivery allowed us to develop a more reliable technology-enabled system. Critical keys to the success of this project include (i) engagement of patients and caregivers in the development of the BAT, (ii) engagement of a multidisciplinary team that met regularly to review data with identification of failure modes and iterative testing of interventions, (iii) clearly defined roles among team members, and (iv) the effective use of technology including EHR-integrated tablets.

We found that caregivers most commonly endorsed forgetting, side effects, poor taste, swallowing difficulties, running out of medicine, and patient refusal while patients endorsed the barriers of forgetting, poor taste, and side effects. As patients transition from childhood to adolescence, the medical regimen ideally becomes a shared responsibility between the patient and caregiver. While external barriers are more easily detected by a caregiver (eg, difficulty swallowing pills), internal factors (eg, embarrassment) can be more challenging to identify. For example, one patient-parent dyad exemplified these differences with the parent endorsing “refuses to take her medication,” as the adherence barrier while the patient endorsed “hates the taste, it’s hard to swallow pills, and she does not want others to know she takes medicine” as a barrier. Unknown to the caregiver, these barriers were perceived as defiance or refusal, but obtaining the patient’s perspective certainly informs the types of adherence promotion strategies we would offer to this family. It is also important to note that as patients grow older, they can experience shifts in their medication-taking behavior, suggesting a need for reassessment of barriers over time.29

When analyzing what adherence barriers the patients and/or their caregivers reported, we found only “fair” concordance between caregiver and patient responses. This confirms that both respondents provide valuable and unique insight regarding adherence barriers and are consistent with previous studies reporting poor agreement between caregiver and patient responses.30,31 Caregiver-endorsed barriers are critical to assess because caregivers typically drive healthcare decision-making, including when to seek help. Patient-endorsed barriers allow us to identify reasons and areas for intervention that may influence subsequent adherence. Similar to previous research,9 forgetting was most commonly endorsed by patients and caregivers and fortunately is amenable to intervention.32,33

Translating the routine assessment of barriers from research to clinical practice is novel and a necessary first step in developing adherence interventions in the clinical setting. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that provider-led adherence promotion efforts are more effective than other evidence-based adherence interventions.34 Nonetheless, our approach does not address all potential barriers to adherence. For instance, our approach relies on patient/caregiver self-awareness and a willingness to report barriers. It is likely that not all caregivers/patients are consciously aware of their barriers or willing to report them. We believe that creating a culture where discussion of adherence barriers is a routine part of care, normalizes the behavior, and will encourage greater willingness to discuss barriers. As an important next step, our team will track patients/caregivers that identify barriers to adherence to investigate whether or not these barriers are associated with clinical outcomes. Additionally, our team has developed patient-centered shared decision-making tools to address specific adherence barriers in clinic, with the goal of improving adherence behaviors and ultimately health outcomes (eg, rejection).

While this is one of the first known clinical implementation studies of routine adherence barriers assessment, it is not without limitations. First, to most effectively demonstrate improvement in our process, we would have ideally collected several more data points in the “baseline assessment period.” However, rather than continuing with a system we knew was unreliable for the sole purpose of further data collection, we applied our learnings to the design of more reliable interventions (EHR-integrated tablets). Second, patients/caregivers were allowed to refuse the BAT and we did not capture reasons for refusal to help us understand this challenge. Anecdotally, some caregivers reported they were uncomfortable using the tablet, which suggests the need for other more preferred methods of completion, such as paper-pencil versions. An important next step in this project is to collect data regarding why certain patients and/or caregivers refuse to complete the BAT. Finally, our barriers data may be biased toward those willing to participate. Nonetheless, we currently have less than 20% refusal at any given visit and more than 90% of our caregivers/patients have completed at least one barriers assessment. Despite these limitations, we believe the principles and approach outlined herein can be applied to many chronic conditions.

In conclusion, we developed and implemented a reliable clinic-based system for assessing barriers to immunosuppressive medications. Assessing barriers not only reveals patient and/or caregiver perceptions but provides a natural opportunity to actively partner with patients and caregivers on patient-centered strategies to optimize adherence. Understanding what barriers our patients and caregivers identity will inform the development of patient-centered adherence interventions that are targeted at individually identified barriers at the point of clinical care, which can be used across pediatric conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would to acknowledge the following individuals of our multidisciplinary team, who without their effort and dedication this work would not be possible: Noelle Bergman, Angel Roudebush, Julie Ross, Denise McAdams, Jodi Engelhardt, Surani Guneratne, Danielle Lazear, John Huber, Andrea Booth, Victoria Hickey, Masa Ashiki, Jack Lennon, Dr. Evie Alessandrini, Dr. John Bucuvalas and the patients and families of the Kidney Transplant Program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Abbreviations

- BAT

barriers assessment tool

- EHR

electronic health record

- PDSA

Plan-Do-Study-Act

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Varnell: Contributed to the design of the study, design of the data collection, acquisition of the data, drafted the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript, and contributed to the analyses; Loiselle: Contributed to the design of the study, design of the data collection, drafted portions of the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript, and contributed to the analyses; Nichols: Contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dahale: Contributed to the design of the study, design of the data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Goebel: Contributed to the conception and design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript; Pai: Contributed to the design of the study, design of the data collection, critical review and revision of the manuscript, and contributed to the analyses; Hooper: Contributed to the conception and design of the study, design of the data collection, critical review and revision of the manuscript, and contributed to the analyses; Modi: Contributed to the conception and design of the study, design of the data collection, critical review and revision of the manuscript, and contributed to the analyses; All authors: Approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2016 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster BJ, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Platt RW, Samuel SM, Hanley JA. Association between age and graft failure rates in young kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;92:1237–1243. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823411d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein SL, Rosburg NM, Warady BA, et al. Pediatric end stage renal disease health-related quality of life differs by modality: A PedsQL ESRD analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1553–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobbels F, Ruppar T, De Geest S, Decorte A, Van Damme-Lombaerts R, Fine RN. Adherence to the immunosuppressive regimen in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:603–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm-Burns MA, Spivey CA, Rehfeld R, Zawaideh M, Roe DJ, Gruessner R. Immunosuppressant therapy adherence and graft failure among pediatric renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2497–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modi AC, Pai AL, Hommel KA, et al. Pediatric self-management: A framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e473–e485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geest SD, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:323–323. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons LE, Blount RL. Identifying barriers to medication adherence in adolescent transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:831–844. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons LE, McCormick ML, Devine K, Blount RL. Medication barriers predict adolescent transplant recipients’ adherence and clinical outcomes at 18-month follow-up. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:1038–1048. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modi AC, Quittner AL. Barriers to treatment adherence for children with cystic fibrosis and asthma: What gets in the way? J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:846–858. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: The collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:282–291. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hommel KA, Baldassano RN. Brief report: Barriers to treatment adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:1005–1010. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modi AC, Crosby LE, Guilfoyle SM, Lemanek KL, Witherspoon D, Mitchell MJ. Barriers to treatment adherence for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and their families. Child Health Care. 2009;38:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modi AC, Monahan S, Daniels D, Glauser TA. Development and validation of the pediatric epilepsy medication self-management questionnaire. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;18:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons LE, McCormick ML, Mee LL, Blount RL. Parent and patient perspectives on barriers to medication adherence in adolescent transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:986–992. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458–464. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.6.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson L. Revising the Pareto chart. Am Stat. 2006;60:332–334. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danziger-Isakov L, Frazier TW, Worley S, et al. Perceived barriers to medication adherence in pediatric and adolescent solid organ transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2016;20:307–315. doi: 10.1111/petr.12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hooper DK, Kirby CL, Margolis PA, Goebel J. Reliable individualized monitoring improves cholesterol control in kidney transplant recipients. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1271–e1279. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies HTO, Powell AE, Nutley SM. Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: Learning from other countries and other sectors—A multimethod mapping study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3(27) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Provost LP, Murray SK. The Health Care Data Guide: Learning from Data for Improvement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: A simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46–51. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muehlhausen W, Doll H, Quadri N, et al. Equivalence of electronic and paper administration of patient-reported outcome measures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted between 2007 and 2013. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:167. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0362-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coons SJ, Eremenco S, Lundy JJ, O’Donohoe P, O’Gorman H, Malizia W. Capturing patient-reported outcome (PRO) data electronically: The past, present, and promise of ePRO measurement in clinical trials. Patient. 2015;8:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loiselle KA, Gutierrez-Colina AM, Eaton CK, et al. Longitudinal stability of medication adherence among adolescent solid organ transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19:428–435. doi: 10.1111/petr.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JL, Eaton C, Gutierrez-Colina AM, et al. Longitudinal stability of specific barriers to medication adherence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:667–676. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan AL, Montepiedra G, Sirois PA, et al. Barriers to medication adherence in HIV-infected children and youth based on self-and caregiver report. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1244–e1251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dayer L, Heldenbrand S, Anderson P, Gubbins PO, Martin BC. Smartphone medication adherence apps: Potential benefits to patients and providers. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53:172–181. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park LG, Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. A quantitative systematic review of the efficacy of mobile phone interventions to improve medication adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:1932–1953. doi: 10.1111/jan.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu YP, Pai ALH. Health care provider-delivered adherence promotion interventions: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1698–e1707. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]