Abstract

Core binding factor β (CBFβ) is a non–DNA-binding partner of all RUNX proteins and critical for transcription activity of CBF transcription factors (RUNXs/CBFβ). In the ovary, the expression of Runx1 and Runx2 is highly induced by the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge in ovulatory follicles, whereas Cbfb is constitutively expressed. To investigate the physiological significance of CBFs in the ovary, the current study generated two different conditional mutant mouse models in which granulosa cell expression of Cbfb and Runx2 was reduced by Cre recombinase driven by an Esr2 promoter. Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice exhibited severe subfertility and infertility, respectively. In the ovaries of both mutant mice, follicles develop normally, but the majority of preovulatory follicles failed to ovulate either in response to human chorionic gonadotropin administration in pregnant mare serum gonadotropin–primed immature animals or after the LH surge at 5 months of age. Morphological and physiological changes in the corpus luteum of these mutant mice revealed the reduced size, progesterone production, and vascularization, as well as excessive lipid accumulation. In granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles and corpora lutea of these mice, the expression of Edn2, Ptgs1, Lhcgr, Sfrp4, Wnt4, Ccrl2, Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr was also drastically reduced. In conclusion, the current study provided in vivo evidence that CBFβ plays an essential role in female fertility by acting as a critical cofactor of CBF transcription factor complexes, which regulate the expression of specific key ovulatory and luteal genes, thus coordinating the ovulatory process and luteal development/function in mice.

Ovarian expression of Cbfb is essential for female fertility and required for the induction of key ovulatory and luteal genes.

The core binding factor (CBF) is a heterodimeric transcription factor complex composed of DNA-binding α subunits and a non–DNA-binding β subunit. There are three genes that encode the α subunit in mammals: Runx1, Runx2, and Runx3. These genes contain a highly conserved runt homology domain, which is responsible for DNA binding (1, 2). The runt homology domain is also responsible for heterodimerization with the β subunit, which is encoded by only one mammalian gene, Cbfb (3–5). CBFβ does not bind to DNA, but it enhances the binding affinity of RUNX proteins to DNA (5) and the stability of RUNX proteins by protecting them from ubiquitin proteasome–mediated degradation (6, 7). Thus, the CBFβ is instrumental for the overall functional activity of RUNX proteins (8–10). RUNX proteins recognize a consensus binding sequence (5′-PyGPyGGTPy-3′) (11) in the promoter or enhancer region of their target genes and act as either a transcriptional activator or repressor, depending on the interaction with other transcriptional modulators (e.g., cotranscription factors or histone modulators) [reviewed in Blyth et al. (12) and Durst and Hiebert (13)].

CBFs play fundamental roles in the development of various tissues, with each RUNX protein exerting a unique role. For instance, RUNX1 is a key regulator of hematopoiesis (14–16). RUNX2 is required for osteoblast differentiation and chondrocyte maturation (17, 18). RUNX3 plays an important role in the growth and differentiation of gut epithelial cells and the development of dorsal root ganglion neurons (19, 20). CBFβ is also required for bone formation and hematopoiesis (8, 21, 22). Mice deficient in Runx1, Runx2, or Cbfb expression die at the embryonic stage or shortly after birth (15–18).

In the ovary, we and others have reported that the expression of both Runx1 and Runx2, but not Runx3, is dramatically increased by the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge in granulosa cells and cumulus cells of preovulatory follicles in mice, rats, and humans (23–26). In rat granulosa cell cultures, the knockdown of Runx1 or Runx2 expression by small interfering RNA affected the expression of several key ovulatory and luteal genes, suggesting that these transcription factors are involved in the ovulatory process and luteinization (23, 24, 27–29). RUNX1 and RUNX2 displayed functional redundancy in regulating gene expression, while RUNX2 acted as a negative regulator for Runx1 expression in luteal cells in rat granulosa cell cultures (27–29), presenting challenges in determining the functional significance of each RUNX protein in the ovary in vivo.

Recently, we have produced a conditional mutant mouse model carrying floxed alleles for Cbfb and Cre recombinase under the control of aromatase (Cyp19) promoter (Cbfbflox/flox × Cyp19cre) (26). Our rationale was to reduce the activity of both RUNX1 and RUNX2 by deleting Cbfb expression in granulosa cells. Female Cbfbflox/flox × Cyp19Cre mice displayed reduced fecundity, with smaller litter sizes, decreased progesterone during gestation, and reduced ovulation rate after superovulation induction compared with those in wild-type animals (26). RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis using cultured granulosa cells isolated from this mutant mouse has revealed altered levels for >200 transcripts (26). However, the expression of even most highly downregulated genes identified in vitro was not altered in periovulatory follicles in vivo, and the reduction of only two genes (Lhcgr and Sfrp4) was verified in corpora lutea (CLs) of mutant mice (26). This discrepancy could be due to the moderate knockout efficiency of Cbfb in preovulatory granulosa cells [∼60% at the level of messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein compared with those of wild-type] and variability among animals (26), stressing the need for a better model with complete ablation of Cbfb expression. Consistent with our findings, other research groups have recently documented the incomplete knockdown of genes in granulosa cells using Cyp19cre mice (30, 31). More importantly, they showed higher efficiency in deleting specific genes in granulosa cells with Cre recombinase driven by the promoter for estrogen receptor 2 (Esr2; Esr2-icre) compared with that with Cyp19cre (30, 31). Therefore, it is critically important to re-examine the impact of CBFs on normal ovarian function and delineate the exact role of CBFβ in periovulatory follicles and CL using a more efficient knockout mouse model.

The objectives of the current study were to generate conditional knockout mice displaying complete ablation of Cbfb expression in the ovary and then evaluate reproductive phenotypes of transgenic mice. This was accomplished by examining ovulation rate, CL development, ovarian morphology, and female fertility and dissecting the mechanisms by which CBFβ controls ovulation and luteal development and function using both immature and adult mice. In the studies presented in this paper, we demonstrated that ovarian expression of Cbfb is essential for female fertility and required for the induction of key ovulatory and luteal genes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animals were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Animal Care and Use Committees. Cbfbflox (9), Runx2flox (32), and Esr2Cre (30) mutant mice were used to generate granulosa cell–specific deletion of Cbfb and Runx2. All mice were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with water and food ad libitum at University of Kentucky Division of Laboratory Animal Resources. For the gonadotropin-induced ovulation model, mice (23 to 25 days old) were injected with pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG; 5 IU intraperitoneally), followed 48 hours later with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; 5 IU intraperitoneally). In this model, the animals ovulated by 12 hours after hCG administration. To determine the stage of the estrous cycle, vaginal fluid and cell samples were obtained from adult female mice (>3 months old) daily for at least 8 days and examined microscopically.

Genotyping

To genotype mice, ear punches were collected and genomic DNA isolated using the AccuStart™ II Mouse Genotyping Kit (Quantabio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted with primers for Cbfb, Runx2, or Esr2 Cre listed in Supplemental Table 1, and amplified PCR products were run on 2% agarose gel for examination.

Collection of granulosa cells and quantification of mRNA levels

Immature female mice (23 to 25 days old) were injected with PMSG (5 IU) to stimulate follicle development and 48 hours later with hCG (5 IU) to induce ovulation and subsequent formation of CLs. Granulosa cells were isolated from ovaries at 12 hours post-hCG via follicular puncture as described previously (26).

Total RNA was isolated from whole mouse ovaries using a TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen) and from granulosa cells using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Levels of mRNA for genes of interest were measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) according to the method described previously (26). The relative amount of transcripts was calculated via the 2−ΔΔCT method (33), normalizing to the mouse gene Rpl19. Oligonucleotide primers for all genes analyzed were designed using the PRIMER3 Program (Supplemental Table 1). Official full names for the genes described in the manuscript are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

In situ localization of Edn2, Ptgs1, Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr mRNA

Ovaries were collected from PMSG/hCG-primed immature mice at defined times after hCG injection or from adult cycling mice on the day of estrus. Frozen ovaries were sectioned at 8 μm and mounted on ProbeOn Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). In situ hybridization analysis was carried out as described previously (26, 34). Briefly, partial complementary DNA fragments were amplified using primers for mouse Edn2, Ptgs1, Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr using total RNA samples isolated from ovaries at 12 hours or 3 days post-hCG. The amplified PCR fragments were cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector. Sequences of the cloned DNA were verified commercially (Eurofins Genomics). Plasmids containing partial complementary DNA for these genes were linearized using the appropriate restriction enzymes. Sense and antisense riboprobes were synthesized using the corresponding linearized plasmids and labeled with fluorescein-12-uridine triphosphate. The ovarian sections hybridized with fluorescein-labeled probes were incubated with the antifluorescein antibody (Roche Applied Sciences). Hybridized riboprobes were amplified using a TSATM Plus Fluorescein Evaluation kit (Roche Applied Sciences). The sections were counterstained with propidium iodide for 10 minutes. Specific signals were visualized with an Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon) under fluorescent optics.

Immunohistochemical analyses and Oil Red O staining

Frozen ovaries were sectioned at 10 μm and mounted on ProbeOn Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Sections were fixed using an appropriate medium (e.g., cold acetone, 4% paraformaldehyde, or 10% formalin solution). The sections were incubated with primary antibodies for RUNX1 (1:100; D33G6; Cell Signaling Technology), RUNX2 (1:200; D1L7F; Cell Signaling Technology), STAR (1:100; D10H12; Cell Signaling Technology), 3βHSD (1:200; HPA009712; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PARM1 [1:200; previously reported in Park et al. (35)], CYP11A1 (1:500; D8F4F; Cell Signaling Technology), or CD31 (1:1000; MEC 13.3; BD Biosciences) at 4°C. After rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline, the sections were incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Life Technologies), counterstained with propidium iodide, and mounted with a mounting medium (Fluoro Gel with DABCO; Electron Microscopy Sciences). Digital images were captured using an Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon), with exposure time kept constant for sections incubated with the same primary antibody.

For Oil Red O staining, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, incubated in 60% isopropyl alcohol for 5 minutes, stained with Oil Red O (Abcam) for 10 minutes, washed in 60% isopropyl alcohol, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted with a mounting medium.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysate was extracted from granulosa cells of Cbfbflox/flox mouse ovaries collected at 12 hours post-hCG using a Nuclear Extraction Kit (Active Motif). Cell lysates were denatured by boiling for 5 minutes, separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated with the primary antibody against CBFβ (1:500; 33516; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a loading control. Blots were incubated with the respective secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour. Peroxidase activity was visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Chemical Co.).

Immunoassay of progesterone

Concentrations of progesterone in serum samples collected from mutant and control mice were measured by a progesterone rat/mouse enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (IBL International). Assay sensitivity was 0.04 ng/mL, and the intra-assay coefficient of variation was 6.8%.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed using the SPSS program (one-way analysis of variance or t test as appropriate; SPSS Inc.) to determine significance. If analysis of variance revealed considerable effects of treatments, the means were compared by Tukey post hoc test. Values were considered significantly different if P < 0.05.

Results

Generation and verification of granulosa cell–specific knockout of Cbfb in mice

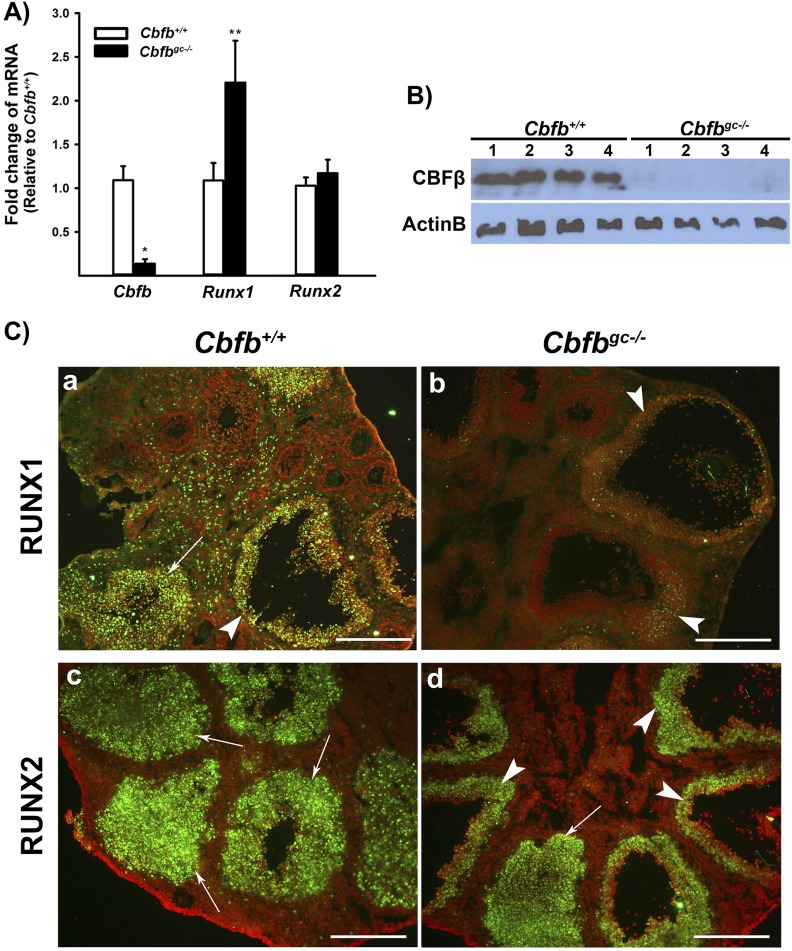

Cbfbflox/flox mice were mated with Esr2Cre/+ mice (30) to produce Cbfbflox/+ × Esr2Cre/+ mice, which were crossed with Cbfbflox/flox mice to generate female Cbfbflox/flox × Esr2Cre/+ (hereafter called Cbfbgc−/−) mice. To verify the deletion efficiency of Cbfb and evaluate the expression of Runx1 and Runx2 in this mutant mouse model, granulosa cells were obtained from Cbfbflox/flox (Cbfb+/+) and Cbfbgc−/− mice at 12 hours after hCG administration. The levels of mRNA and protein for Cbfb were ∼90% lower in Cbfbgc−/− compared with Cbfb+/+ mice (Fig. 1A and 1B). In contrast, the mean values of Runx1 mRNA levels had a tendency to be higher (P = 0.068) in Cbfbgc−/− mice, whereas Runx2 mRNA levels were not different compared with Cbfb+/+ mice. As expected, in control animals, immune-positive staining for RUNX1 and RUNX2 was localized to granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles and newly forming CL (Fig. 1Ca and 1Cc). However, in Cbfbgc−/− mice (Fig. 1Cb and 1Cd), the staining intensity for RUNX1 was reduced, whereas RUNX2 staining in periovulatory follicles and newly forming CL was comparable to those in control mice. These data suggested that in the absence of CBFβ, RUNX1 protein became unstable and was likely ubiquitinated, whereas RUNX2 protein stability was less dependent on CBFβ at 12 hours after hCG administration.

Figure 1.

Expression of Cbfb, Runx1, and Runx2 in ovaries of Cbfbflox/flox × Esr2cre/+ (Cbfbgc−/−) mice. Granulosa cells isolated from ovaries collected at 12 hours post-hCG from PMSG-primed immature mice. (A) Levels of mRNA for Cbfb, Runx1, and Runx2 were measured by qPCR and normalized to the Rpl19 value in each sample (n = 10 animals per genotype). (B) CBFβ protein was detected by Western blots. The membrane was reprobed with a monoclonal antibody against β-actin (ActinB) to assess the loading of protein in each lane (n = 4 animals per genotype). (C) Immunohistochemical detection of (a and b) RUNX1 and (c and d) RUNX2 in ovaries of control and mutant mice collected at 12 hours post-hCG (n = 3 animals per genotype). Immune-positive nuclear staining for RUNX1 or RUNX2 proteins (green) was localized to granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles and newly forming CLs. Arrowheads and arrows point to granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles and newly forming CLs, respectively. RUNX1 staining was also localized to leukocytes. The sections were counterstained with propidium iodide (red) for nuclear staining. Scale bars, 250 μm. *P < 0.0001; **P = 0.068.

Deletion of Cbfb in granulosa cells results in loss of fertility

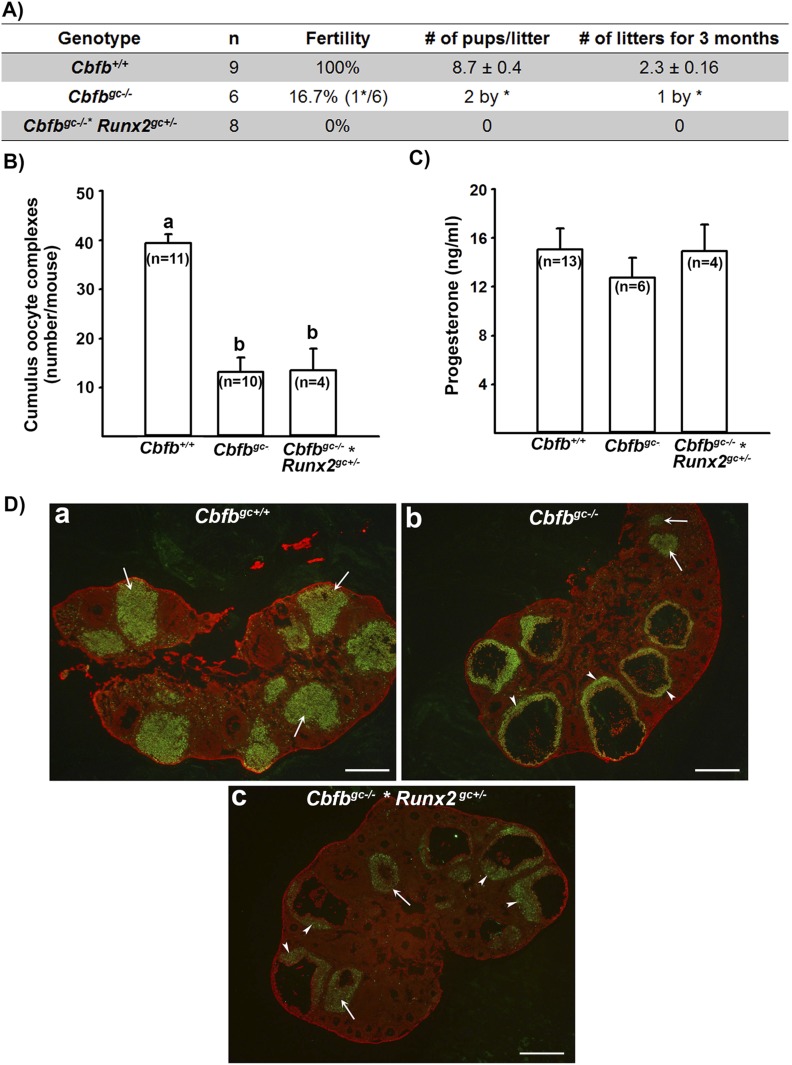

To determine the reproductive capacity, six Cbfbgc−/− females at 2 months of age were subjected to a fertility test by mating with males of proven fertility for 3 months. Five of the Cbfbgc−/− mice showed no sign of pregnancy (e.g., pregnant-associated weight gain and pups), whereas one became pregnant and delivered two pups during 3 months of breeding test, exhibiting subfertility phenotype (Fig. 2A). Because Cbfbgc−/− mice showed subfertility phenotype with no visible reduction of RUNX2 protein in the ovary (Fig. 1C), we questioned whether the reduction of Runx2 expression in this mutant mouse model would result in a stronger impact on female fertility. To accomplish this, we introduced Runx2flox to Cbfbgc−/− mice by mating female Cbfbflox/flox × Runx2flox/flox mice with male Cbfbflox/flox × Esr2Cre/+ mice and produced Cbfbflox/flox × Runx2flox/+ × Esr2Cre/+ (Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/−) mice. Immunohistochemical analysis of RUNX2 protein in the ovary of Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice showed the reduced staining intensity for RUNX2 in periovulatory follicles and CLs (Fig. 2Dc and Supplemental Fig. 1) compared with wild-type and Cbfbgc−/− mice. These results confirmed the reduction of Runx2 expression by the deletion of one copy of the Runx2 gene in granulosa cells. All eight Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− females subjected to a fertility test for 3 months produced no pups, exhibiting infertility phenotype (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we have included this animal model in subsets of experiments.

Figure 2.

Ovarian phenotypes of Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice: fecundity, ovulation rate, progesterone, and ovarian morphology. (A) At 2 months old, wild-type (Cbfb+/+), Cbfbgc−/−, and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice were mated with fertile males for 3 months. *Represents the mouse that became pregnant and was observed with two dead pups on the day of delivery. (B) Immature mice were administered with PMSG/hCG to induce superovulation. The animals were euthanized between 16 and 24 hours after hCG injection, and cumulus oocyte complexes were collected from oviducts and counted. (C) Levels of serum progesterone were measured in blood samples collected between 12 and 16 hours after hCG administration. The number inside each bar represents the sample size of mice used for each experiment. Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05). (D) Ovaries collected at 16 hours post-hCG were immunostained for RUNX2 (green) and counterstained with propidium iodide (red). RUNX2 staining was used to locate periovulatory follicles and newly forming CL. RUNX2 staining was reduced in (c) Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice compared with (a) Cbfbgc+/+ and (b) Cbfbgc−/− mice. Arrows and arrowheads represent newly forming CLs and periovulatory follicles, respectively. Scale bars, 500 μm.

Deletion of Cbfb in granulosa cells results in reduced ovulation and altered expression of specific genes in ovulatory follicles and CL in superovulation-induced immature mice

To determine whether the ovulatory process was affected in these mutant mouse models, superovulation was induced in immature animals by PMSG/hCG. The number of cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) collected in oviducts was significantly lower in both Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice compared with that in Cbfb+/+ mice (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, levels of serum progesterone did not differ among wild-type and two mutant mouse models after superovulation induction (Fig. 2C). To determine whether the reduced ovulation rate was due to the defects in follicle development or the ovulation process, the ovaries collected at 16 hours after hCG administration were examined for morphological analysis by immunostaining for RUNX2, as this protein is mainly localized to periovulatory follicles and CLs. As expected, the ovaries of wild-type animals contained multiple newly forming CLs (Fig. 2Da), whereas both Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice showed many periovulatory follicles with COCs and a few forming CLs (Fig. 2Db and 2Dc). These data indicated that follicles developed to the preovulatory stage, yet many of these follicles failed to ovulate.

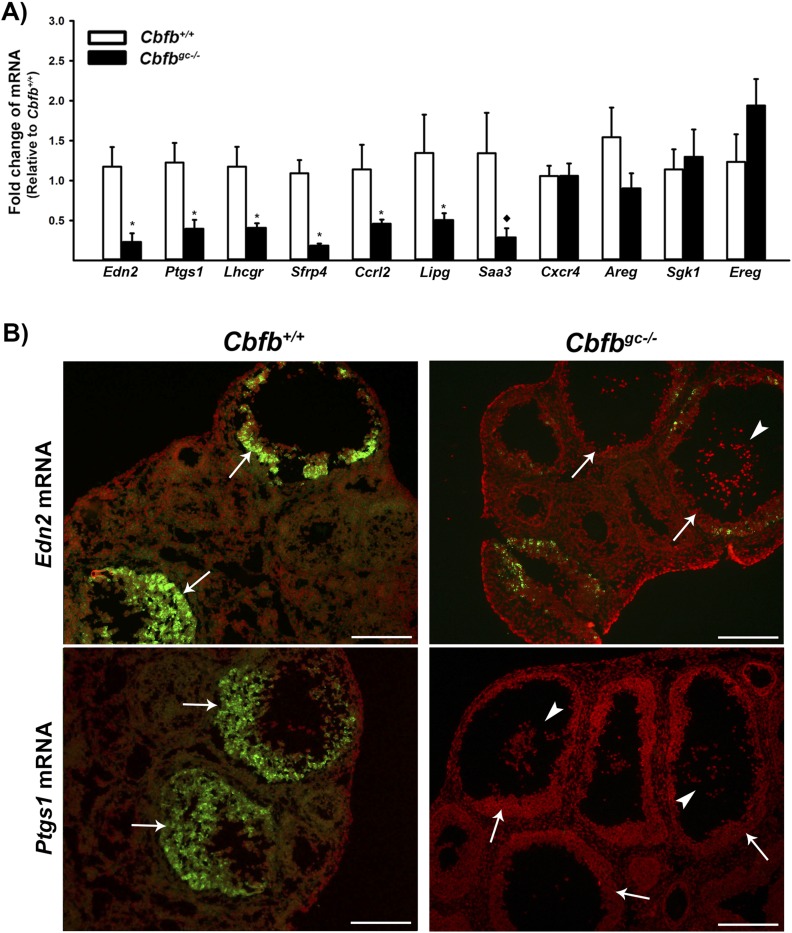

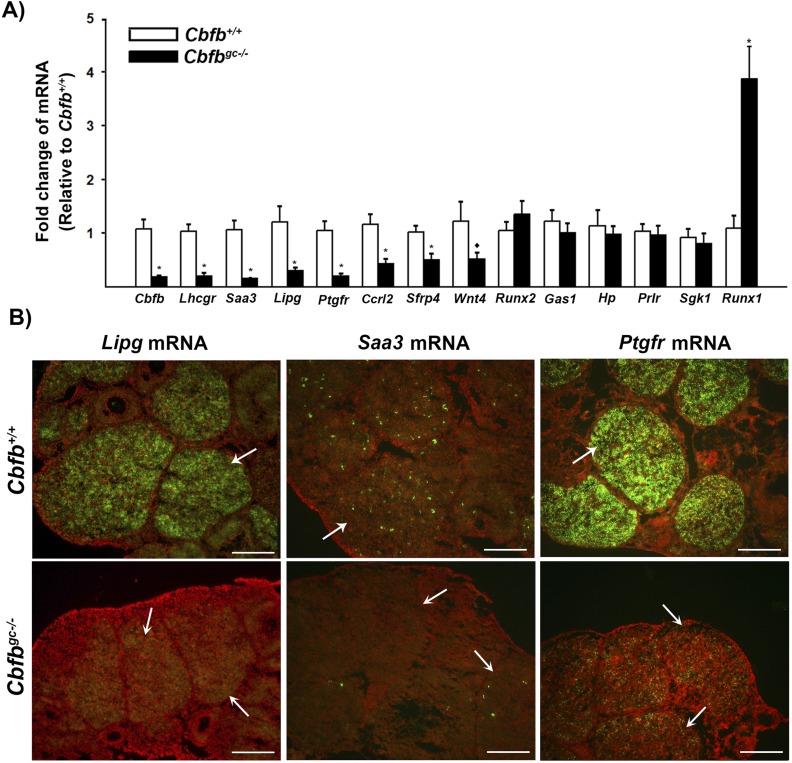

To determine the mechanisms by which Cbfb deletion impacts ovulation, granulosa cells isolated from the ovary at 12 hours after hCG administration were analyzed for potential target genes. We selected a dozen genes for which levels were downregulated in granulosa cells from Cbfbflox/flox × Cyp19cre mice compared with those from wild-type mice in our previous RNA-Seq data (26). In that study, the granulosa cells were cultured for 12 and 24 hours with hCG and used for RNA-Seq analyses to identify differentially regulated genes (26). As shown in Fig. 3A, the levels of mRNA for Edn2, Ptgs1, Lhcgr, Sfrp4, Ccrl2, Lipg, and Saa3 were drastically reduced in granulosa cells isolated from ovaries of Cbfbgc−/− compared with those of Cbfb+/+ females at 12 hours post-hCG. Particularly, the expression of Edn2 and Ptgs1 was known to be transiently upregulated and highest around the time of ovulation (36–38). In situ hybridization analysis also confirmed the high expression of Edn2 and Ptgs1 in granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles (arrows) in Cbfb+/+ mice and the lack or low expression of these genes in Cbfbgc−/− females (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Identification of the transcripts differentially expressed in granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles in Cbfbgc−/− mice. (A) Granulosa cells were isolated from the ovaries collected at 12 hours post-hCG. The levels of mRNA for potential downstream target genes of CBFs were measured by qPCR, normalizing to the Rpl19 value in each sample (n = 10 for Cbfb+/+ and n = 11 for Cbfbgc−/− mice). (B) Transcripts for Edn2 and Ptgs1 were evaluated via in situ hybridization analyses in ovaries collected at 12 hours post-hCG from Cbfb+/+ and Cbfbgc−/− mice (n = 3 per genotype). Transcripts for these genes were detected as green fluorescence signals. The tissue sections were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). Arrows and arrowheads represent periovulatory follicles and expanded COCs, respectively. Scale bars, 200 μm. *P < 0.05; ♦P = 0.09.

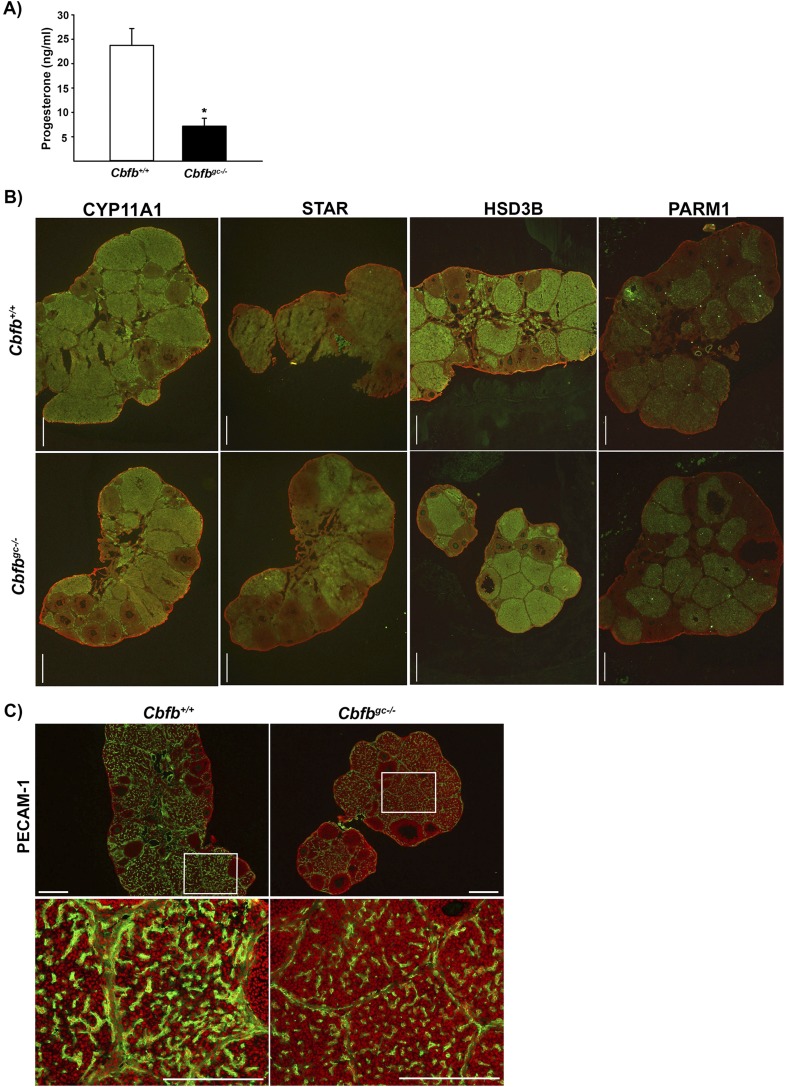

We evaluated the impact of granulosa cell deletion of Cbfb in the development of CL using ovaries collected 3 days after hCG stimulation. The levels of serum progesterone were significantly lower in Cbfbgc−/− mice compared with control animals (Fig. 4A). Yet, no visible differences were detected in terms of immunopositive staining for CYP11A1, HSD3B, STAR, and PARM1 in the CL between Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfb+/+ mice (Fig. 4B). These data indicated that low progesterone levels detected in Cbfbgc−/− mice are not due to changes in proteins known to be involved in ovarian progesterone production (e.g., CYP11A1, HSD3B, and STAR) and metabolism [e.g., PARM1 (35)].

Figure 4.

Assessment of progesterone production, the expression of genes involved in steroid production and metabolism, and vascularization in the CL of wild-type and Cbfbgc−/− mice. (A) The levels of serum progesterone were measured in blood samples collected 3 days after hCG administration (n = 5 for Cbfb+/+ and n = 6 for Cbfbgc−/− mice). (B) Immunohistochemical analyses of CYP11A1, STAR, HSD3B, and PARM1 protein in the ovary collected 3 days post-hCG (n = 3 animals per genotype). (C) Immunohistochemical analyses of PECAM-1 protein in the ovary collected 3 days post-hCG (n = 3 animals per genotype). White boxes in the top panel are magnified in the bottom panel. Green represents positive staining for these proteins in each section. Propidium iodide (red) was used to counterstain the tissue. Scale bars, 500 μm. *P < 0.001.

We also assessed the expression of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1; CD31) to determine whether luteal angiogenesis was affected in Cbfbgc−/− mice. Positive staining for PECAM-1 was localized to endothelial cells in the thecal layer and CL of both wild-type and Cbfbgc−/− mice (Fig. 4C). However, the staining intensity appears to be weaker in the CL of Cbfbgc−/− mice compared with that of wild-type mice.

To identify the genes that have a potential to impact the development and function of CL, a dozen genes for which expression was differentially regulated by Cbfb knockdown in cultured granulosa cells at 24 hours after hCG stimulation were selected from our previous RNA-Seq data (26). Among the genes selected, the levels of mRNA for Lhcgr, Saa3, Lipg, Ptgfr, Ccrl2, Sfrp4, and Wnt4 were significantly lower in Cbfbgc−/− mice compared with those in control mice (Fig. 5A). In situ localization analysis of Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr mRNA demonstrated high expression of these genes exclusively in the CL of control mice (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, Saa mRNA was localized inside the CL in a punctuated manner, whereas Lipg and Ptgfr mRNA were evenly distributed throughout the CL. Of note, both Saa3 and Lipg [endothelial lipase (EL)] are known to be associated with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) that transports cholesterol to steroidogenic organs such as gonads and adrenals (39, 40). As expected in Cbfbgc−/− mice, minimal or reduced expression of Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr mRNA was detected in the CL.

Figure 5.

Identification of the transcripts differentially expressed in the CL of Cbfbgc−/− mice. (A) Ovaries were collected 3 days post-hCG. The levels of mRNA for potential downstream target genes of CBFs were measured by qPCR, normalizing to the Rpl19 value in each sample (n = 9 to 10 animals per genotype). (B) Transcripts for Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr were evaluated via in situ hybridization analyses in ovaries collected 3 days post-hCG from Cbfb+/+ and Cbfbgc−/− mice (n = 3 per genotype). Transcripts for these genes were detected as green fluorescence signals. Propidium iodide (red) was used to counterstain the tissue. CL indicated by arrows. Scale bars, 200 μm. *P < 0.05; ♦P = 0.09.

Deletion of Cbfb in granulosa cells results in reduced ovulation and defective CL development in mature animals

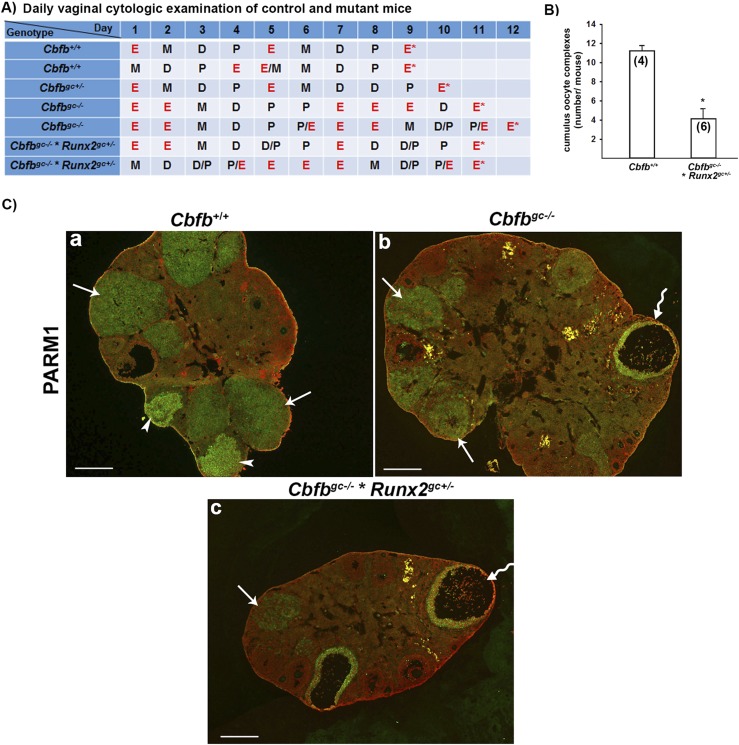

To determine whether Cbfb deletion in granulosa cells affects the estrous cycle, adult animals were subjected to daily vaginal cytology. Both Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− females appeared to stay longer in estrus than control mice, suggesting some degree of disturbance in the estrous cycle (Fig. 6A). To verify that the inhibitory impact of Cbfb deletion on ovulation and CL development observed in immature mice after superovulation induction occurs in adult animals, ovaries and oviducts were collected in the morning (1100 hours) of estrus (E* in Fig. 6A). This is the time point when COCs can be counted in the oviduct because normally ovulation has already occurred, and newly formed CL is easily distinguished from the CL generated from previous cycles in the ovary. The number of COCs collected in the oviduct was 64% reduced in Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice compared with control animals (Fig. 6B). To examine the ovarian morphology of these animals, ovarian sections were subjected to immunostaining for PARM1. As Parm1 expression is induced in preovulatory follicles only after the LH surge, and its expression continues in the CL (35), PARM1 staining can be used to identify periovulatory follicles and CL. As expected, newly forming CL as well as well-developed large CL generated from previous cycles were observed in ovaries of wild-type mice collected in the morning of estrus (Fig. 6Ca). Meanwhile, mutant mouse ovaries displayed large follicles containing expanded COCs (wavy arrows in Fig. 6Cb and 6Cc). These follicles stained positive for PARM1, indicating that these follicles have already responded to the LH surge, but failed to ovulate. In addition, compared with the ovary of control mice exhibiting the CL of varying size, mutant mouse ovaries were devoid of the large CL, suggesting compromised CL development (Fig. 6C and Figs. 7 and 8).

Figure 6.

Assessment of estrous cycling pattern, ovulation rate, and ovarian morphology of adult wild-type and mutant mice. (A) Animals (5 months old) were subjected to daily examination of vaginal smear for at least two cycles and euthanized in the morning of estrus (E). (B) COCs were collected from oviducts of animals euthanized in the morning of estrus (E*) and counted. The number inside each bar represents the sample size of mice evaluated. (C) Ovarian morphology of these animals was examined by immunostaining the tissue sections for PARM1 (n = 3 animals per genotype). PARM1 staining (green) was localized to periovulatory follicles [wavy arrows in (b) and (c)], newly formed CL [arrowheads in (a)], and CL from previous cycles [arrows in (a)–(c)]. High lipid/fat was visible in yellow under the fluorescent microscope in mutant mouse ovaries (also seen in Fig. 8). Propidium iodide (red) was used to counterstain the tissue. Scale bars, 500 μm. *P < 0.001. D, diestrus; M, metestrus; P, proestrus.

Figure 7.

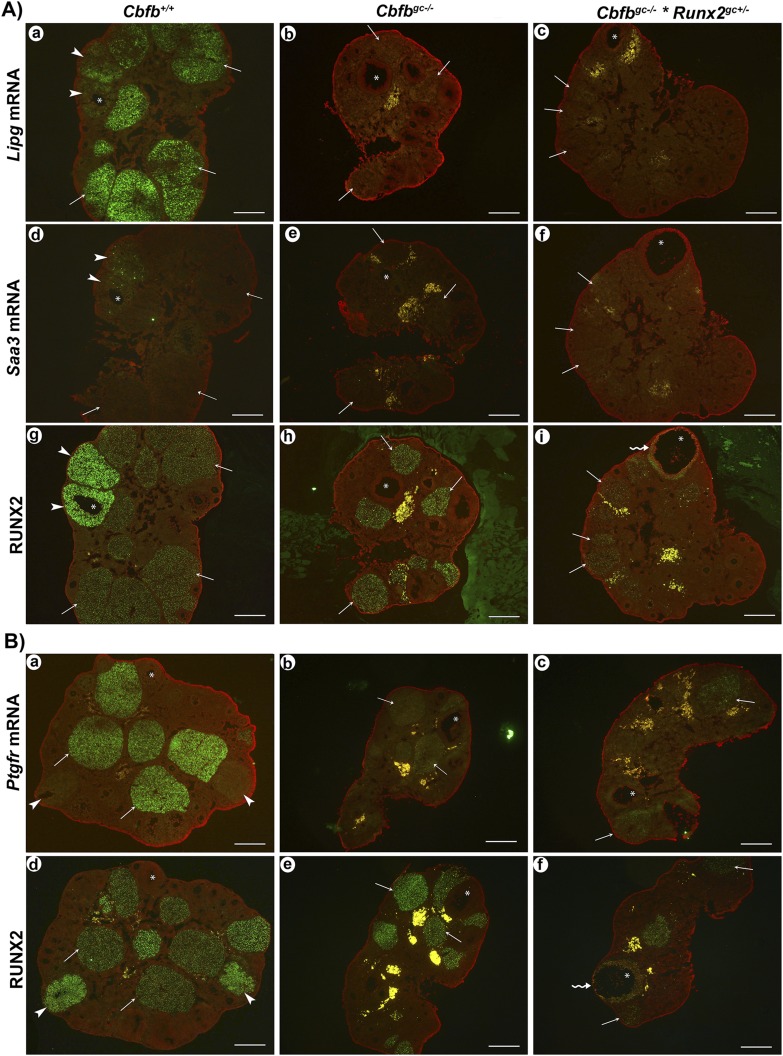

Assessment of the expression of Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr in the ovary of adult wild-type and mutant mice. Ovaries collected on the day of estrus were used to examine mRNA for (Aa–Ac) Lipg, (Ad–Af) Saa3, and (Ba–Bc) Ptgfr by in situ hybridization analyses (n = 3 animals per genotype). Transcripts for these genes were detected as green fluorescence signals. The ovarian sections were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). (A and B) The symbol * was placed in the same structure in serial sections of the same ovary for orientation, and (Ag–Ai and Bd–Bf) RUNX2 staining was used to locate periovulatory follicles and CL. Arrowheads, arrows, and wavy arrows point to newly formed CL, CL from previous cycles, and periovulatory follicles in serial sections of the same ovary, respectively. Scale bars, 500 μm.

Figure 8.

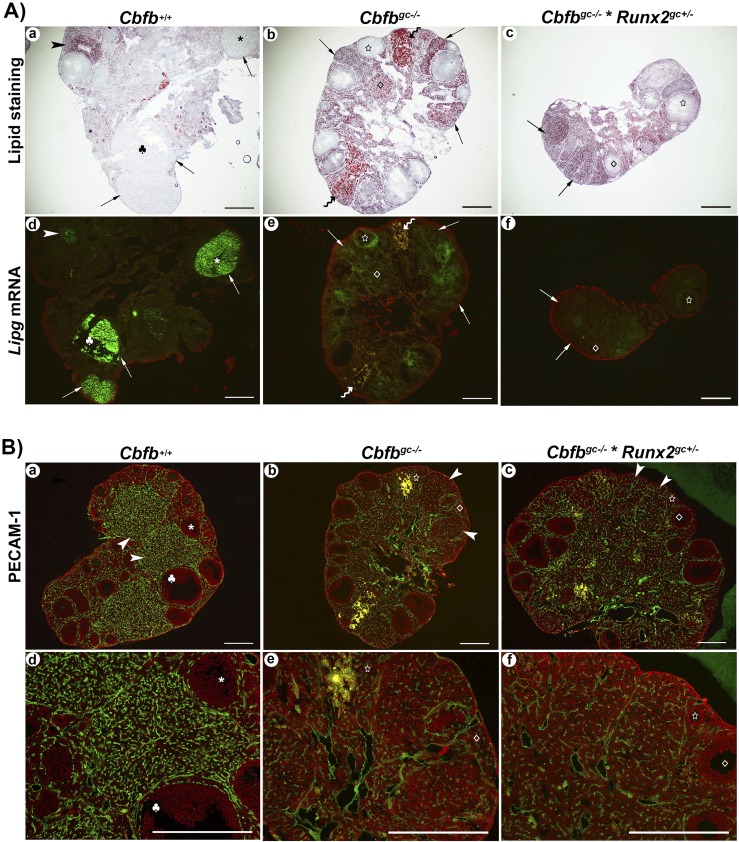

Assessment of lipid accumulation and vascularization in the ovary of adult wild-type and mutant mice. Ovaries collected on the day of estrus were used for (Aa–Ac) Oil Red O staining and (Ba–Bc) PECAM-1 staining. Different symbols (e.g., *, ♣, ◊) were placed in the same structure in serial sections for orientation. (A) Arrows point to the CL. Wavy arrows point to the CL with high lipid/fat that is also visible in yellow under the fluorescent microscope in the serial section of the same ovary. (Ba–Bc) Arrowheads point to the CL, which was magnified in the (Bd–Bf) bottom panel. Positive signals for (Ad–Af) Lipg mRNA and (Ba–Bc) PECAM-1 protein were detected as green fluorescence signals. Propidium iodide (red) was used to counterstain the tissue. Scale bars, 500 μm.

We determined whether the reduced expression of specific luteal genes in the CL of immature Cbfbgc−/− mice after superovulation induction also occurs in the CL of adult animals. Because the expression pattern of Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr in the CL of cycling mice has not been determined, transcripts for these genes were localized in the ovary of adult mice collected on the day of estrus by in situ hybridization analysis (Fig. 7). To locate periovulatory follicles and CL, serial sections of the same ovary were immunostained for RUNX2. Newly formed CLs (arrowheads in Fig. 7) were distinguished from the CL generated from previous cycles (arrows in Fig. 7) based on CL morphology and RUNX2 staining intensity. In wild-type mice, Lipg mRNA was localized to CL, with stronger signals in large, well-developed CL compared with newly formed CL (Fig. 7Aa). Saa3 mRNA was localized exclusively to newly formed CL (Fig. 7Ad). The high expression of Ptgfr mRNA was localized to large CL (Fig. 7Ba), but not in the newly formed CL (arrowheads). In Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice, none of the CL showed strong signals for Lipg, Saa3, and Ptgfr mRNA.

In addition, Oil Red O staining indicated the excessive lipid accumulation in most of the CL in the ovary of adult Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice (Fig. 8Ab and 8Ac), whereas lipid staining was less visible in the large CL of control animals (Fig. 8Aa). It is worthwhile to note that even in control mouse ovaries, a few CLs, which appear to be structurally regressing, showed abundant lipid staining (arrowhead in Fig. 8Aa). In a serial section of the same ovary (Fig. 8Ad), intensive signals for Lipg mRNA were detected in the large CL, which displayed low lipid staining, whereas the CL with high lipid staining showed reduced expression of Lipg mRNA (arrowhead in Fig. 8Ad). As expected, mutant mouse ovaries showed little expression for Lipg mRNA in the CL. Together, these data suggest an inverse relationship between Lipg expression and lipid accumulation. Similar to that observed in PMSG/hCG models, the large CL of wild-type mice showed well-developed vasculature as evident by abundant and intensive PECAM-1 staining throughout the CL (Fig. 8Ba). PECAM-1 was also detected inside the CL of Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice (Fig. 8Bb and 8Bc), but PECAM-1 staining was less abundant inside the CL of these mice compared with that in wild-type mice.

Discussion

Successful ovulation and subsequent formation and development of the CL are essential for female fertility. Failure of these processes results in pathological conditions in women such as polycystic ovary syndrome (41), luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome (42), and CL insufficiencies (43). The activation of the LH receptor (Lhcgr) by the preovulatory LH surge initiates these processes by inducing specific transcription factors that regulate the expression of diverse intra- and extracellular factors to execute precisely regulated actions in periovulatory follicles. The current study demonstrated that CBFs are such specific transcription factors necessary for successful ovulation and luteal development and function. This claim is supported by the evidence that conditional deletion of components of CBFs in granulosa cells of the ovary (Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/−) resulted in severe subfertility and infertility, respectively, in female mice. These mice displayed reduced ovulation rate, presence of large follicles with entrapped expanded COCs beyond normal ovulation timing, absence of mature/well-developed CL, reduced progesterone levels during luteal development, and reduced expression of key ovulatory and luteal genes.

Previous studies have documented that the LH surge/hCG increases the expression of Runx1 and Runx2 in granulosa cells of preovulatory follicles, whereas Cbfb is constitutively expressed in the ovary (23–26). Although the expression of Runx1 was transient in ovulatory follicles, Runx2 expression continued in the CL (26). In search of the specific function and physiological significance of CBFs in the ovary, we previously used Cbfbflox/flox × Cyp19Cre mice. Although this model indicated that CBFβ plays an important role in normal ovarian function, several phenotypic changes observed were rather mild and variable among animals due to incomplete deletion of Cbfb expression (26). Using mouse models exhibiting more efficient and consistent deletion of Cbfb in the ovary, the current study has not only extended previous findings but also showed profound defects in ovulation and luteal development, resulting in detrimental impacts on fertility. In delineating how the deletion of Cbfb resulted in reduced and defective ovulation, we have screened the expression of a dozen genes and verified several of them as regulated by CBFs in the ovulatory follicle (e.g., Edn2, Ptgs1, Lhcgr, Sfrp4, Ccrl2, Lipg, and Saa3). Of particular interest is Edn2, for which expression is highly and transiently induced after hCG administration and drastically reduced in periovulatory follicles of Cbfb knockout mice. EDN2 is a potent vasoconstrictor and has been reported to play a critical role in follicle rupture via vasoconstriction of thecal vessels (44, 45). Previous reports have supported this idea by demonstrating that conditional deletion of Edn2 in the ovary resulted in reduced ovulation rate (30, 46). Therefore, the dramatic reduction of Edn2 expression could be one of the reasons contributing to defective ovulatory phenotype in Cbfb knockout mice.

In mutant mouse models, many ovulatory follicles failed to rupture and release COCs, but some of the follicles managed to ovulate expanded COCs. These results indicated that additional ovarian defects prevented these animals from being fertile. In agreement with this idea, we also observed distinct morphological and physiological changes in the CL of Cbfb-deficient mice. Notably, the ovaries of mutant mice were devoid of well-developed CL, but riddled with small CL exhibiting excessive lipids and hampered vascular development, as evidenced by intensive Oil Red O staining and reduced immunostaining for PECAM-1, a marker for endothelial cells, respectively. Together with the evidence showing a marked reduction of progesterone production, these data point to the impaired development of the CL and possible defects in the steroidogenic pathway in Cbfb-deficient mice. Indeed, the expression of Lhcgr, Sfrp4, and Wnt4, which are known to be involved in CL development, was drastically reduced in the CL of Cbfbgc−/− mice (47–50). In the same ovary, however, the expression of genes that are known to be associated with progesterone production and metabolism, such as CYP11A1, STAR, HSD3B, and PARM1, was not altered in Cbfbgc−/− mice compared with that of wild-type animals. Among the genes highly downregulated in the CL of Cbfb-deficient mice included Lipg, Saa3, and Ccrl2. Saa3 is an isoform of serum amyloid A proteins and belongs to a family of apolipoproteins associated with HDL in the plasma (39). Our in situ hybridization analysis revealed that the expression of this gene was localized to the subpopulation of cells exclusively in newly formed CL of wild-type animals. This finding is consistent with a recent study reporting intense yet spotty signals for Saa3 mRNA in newly forming CL in a superovulation-induced mouse model (51). Although the identity of Saa3-expressing cells and the exact role of serum amyloid A3 in the CL remain to be determined, the current study indicated that CBFs affect the expression of this gene during early development of the CL.

Lipg encodes a protein, EL, with preferential phospholipase activity (40). In addition to its lipase activity, EL was shown to increase the binding of HDL particle and uptake of HDL-cholesteryl ester in HepG2 cells infected with EL-expressing adenovirus (52). Lipg-null mice showed increased fasting plasma levels of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and phospholipids (53), and the in vivo overexpression of EL reduced cholesterol efflux (54). In Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice, all of the CL showed reduced Lipg mRNA but were imbued with many lipid droplets, suggesting impaired lipid or cholesterol metabolism. Therefore, it is conceivable that the lack of Lipg expression is, in part, responsible for defective lipid or cholesterol metabolism and reduced progesterone production in the compromised CL of Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice.

Another intriguing finding was the dramatic reduction of Ptgfr expression in all of the CL of Cbfb-deficient mice. Prostaglandin F2a is well known as an inducer of luteolysis in domestic animals, and knockout mice lacking its receptor (Ptgfr) were unable to undergo parturition due to a failure to induce luteolysis and diminish prepartum progesterone levels (55). We found the abundant expression of Ptgfr in the mature CL, but low signals in newly formed CL in cycling mice. At present, the role of the prostaglandin F receptor in mature CL is unknown in mice. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether the reduction of Ptgfr expression is related with defective CL development or regression in Cbfbgc−/− mice.

The current study demonstrated that the expression of Edn2, Ptgs1, Lhcgr, Saa3, Sfrp4, Ccrl2, Lipg, and Ptgfr was downregulated in periovulatory follicles and/or CL of Cbfbgc−/− mice, indicating that these genes may be potential targets of CBFs (e.g., RUNX1/CBFβ and RUNX2/CBFβ). However, it remains to be determined whether these genes are direct transcription targets of CBFs or the expression of these genes is indirectly affected by a sequence of steps influenced by Cbfb deletion. Also, Cbfb deletion in granulosa cells resulted in the reduced transcriptional activity of CBFs, but not the expression of Runx1 and Runx2 in the ovary. In fact, the levels of Runx1 mRNA were increased, although its stability appeared to be reduced during the ovulatory period (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the expression of Runx2 was not altered in Cbfbgc−/− mice. These findings suggest that, albeit reduced transcriptional activity, RUNX1 and RUNX2 may maintain some activity in periovulatory granulosa cells and luteal cells in Cbfbgc−/− and Cbfbgc−/− × Runx2gc+/− mice. Therefore, it will be of great interest to determine whether deletion of both Cbfb and Runx1/2 genes in mice would result in complete anovulation and failure in luteal formation. Overall, the current study provided conclusive in vivo evidence that CBFβ plays an essential role in female fertility by regulating the expression of genes critical for ovulation and luteal development and function in mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Thomas E. Curry, Jr., and Patrick Hannon for critical reading of the manuscript.

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO3HD066012 and P01HD071875 (to M.J.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CBF

core binding factor

- CBFβ

core binding factor β

- CL

corpus luteum

- COC

cumulus oocyte complex

- EL

endothelial lipase

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PECAM-1

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- PMSG

pregnant mare serum gonadotropin

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing

References

- 1. Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Kagoshima H, Inuzuka M, Lu J, Satake M, Shigesada K, Ito Y. PEBP2/PEA2 represents a family of transcription factors homologous to the products of the Drosophila runt gene and the human AML1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(14):6859–6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurusu S, Sakaguchi S, Kawaminami M, Hashimoto I. Sustained activity of luteal cytosolic phospholipase A2 during luteolysis in pseudopregnant rats: its possible implication in tissue involution. Endocrine. 2001;14(3):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meyers S, Downing JR, Hiebert SW. Identification of AML-1 and the (8;21) translocation protein (AML-1/ETO) as sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins: the runt homology domain is required for DNA binding and protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(10):6336–6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bae SC, Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Oka H, Satake M, Shigesada K, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Ito Y. PEBP2 alpha B/mouse AML1 consists of multiple isoforms that possess differential transactivation potentials. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(5):3242–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogawa E, Inuzuka M, Maruyama M, Satake M, Naito-Fujimoto M, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Molecular cloning and characterization of PEBP2 beta, the heterodimeric partner of a novel Drosophila runt-related DNA binding protein PEBP2 alpha. Virology. 1993;194(1):314–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang G, Shigesada K, Ito K, Wee HJ, Yokomizo T, Ito Y. Dimerization with PEBP2beta protects RUNX1/AML1 from ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. EMBO J. 2001;20(4):723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qin X, Jiang Q, Matsuo Y, Kawane T, Komori H, Moriishi T, Taniuchi I, Ito K, Kawai Y, Rokutanda S, Izumi S, Komori T. Cbfb regulates bone development by stabilizing Runx family proteins. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(4):706–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Q, Stacy T, Miller JD, Lewis AF, Gu TL, Huang X, Bushweller JH, Bories JC, Alt FW, Ryan G, Liu PP, Wynshaw-Boris A, Binder M, Marín-Padilla M, Sharpe AH, Speck NA. The CBFbeta subunit is essential for CBFalpha2 (AML1) function in vivo. Cell. 1996;87(4):697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naoe Y, Setoguchi R, Akiyama K, Muroi S, Kuroda M, Hatam F, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. Repression of interleukin-4 in T helper type 1 cells by Runx/Cbf beta binding to the Il4 silencer. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1749–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sasaki K, Yagi H, Bronson RT, Tominaga K, Matsunashi T, Deguchi K, Tani Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Absence of fetal liver hematopoiesis in mice deficient in transcriptional coactivator core binding factor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(22):12359–12363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leiden JM, Thompson CB. Transcriptional regulation of T-cell genes during T-cell development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6(2):231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blyth K, Cameron ER, Neil JC. The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Durst KL, Hiebert SW. Role of RUNX family members in transcriptional repression and gene silencing. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4220–4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Friedman AD. Cell cycle and developmental control of hematopoiesis by Runx1. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219(3):520–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okuda T, van Deursen J, Hiebert SW, Grosveld G, Downing JR. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell. 1996;84(2):321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Q, Stacy T, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe AH, Speck NA. Disruption of the Cbfa2 gene causes necrosis and hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and blocks definitive hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3444–3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89(5):755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89(5):747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li QL, Ito K, Sakakura C, Fukamachi H, Inoue K, Chi XZ, Lee KY, Nomura S, Lee CW, Han SB, Kim HM, Kim WJ, Yamamoto H, Yamashita N, Yano T, Ikeda T, Itohara S, Inazawa J, Abe T, Hagiwara A, Yamagishi H, Ooe A, Kaneda A, Sugimura T, Ushijima T, Bae SC, Ito Y. Causal relationship between the loss of RUNX3 expression and gastric cancer. Cell. 2002;109(1):113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inoue K, Ozaki S, Shiga T, Ito K, Masuda T, Okado N, Iseda T, Kawaguchi S, Ogawa M, Bae SC, Yamashita N, Itohara S, Kudo N, Ito Y. Runx3 controls the axonal projection of proprioceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(10):946–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elvin JA, Clark AT, Wang P, Wolfman NM, Matzuk MM. Paracrine actions of growth differentiation factor-9 in the mammalian ovary. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(6):1035–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller J, Horner A, Stacy T, Lowrey C, Lian JB, Stein G, Nuckolls GH, Speck NA. The core-binding factor beta subunit is required for bone formation and hematopoietic maturation. Nat Genet. 2002;32(4):645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jo M, Curry TE Jr. Luteinizing hormone-induced RUNX1 regulates the expression of genes in granulosa cells of rat periovulatory follicles. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(9):2156–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park ES, Lind A-K, Dahm-Kähler P, Brännström M, Carletti MZ, Christenson LK, Curry TE Jr, Jo M. RUNX2 transcription factor regulates gene expression in luteinizing granulosa cells of rat ovaries. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(4):846–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Richards JS. Paracrine and autocrine regulation of epidermal growth factor-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes and granulosa cells: key roles for prostaglandin synthase 2 and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(6):1352–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson K, Park J, Curry TE Jr, Mishra B, Gossen J, Taniuchi I, Jo M. Core binding factor-β knockdown alters ovarian gene expression and function in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2016;30(7):733–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu J, Park ES, Curry TE Jr, Jo M. Periovulatory expression of hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (Hapln1) in the rat ovary: hormonal regulation and potential function. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(6):1203–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu J, Park ES, Jo M. Runt-related transcription factor 1 regulates luteinized hormone-induced prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 expression in rat periovulatory granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150(7):3291–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park ES, Park J, Franceschi RT, Jo M. The role for runt related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) as a transcriptional repressor in luteinizing granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;362(1-2):165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cacioppo JA, Lin PP, Hannon PR, McDougle DR, Gal A, Ko C. Granulosa cell endothelin-2 expression is fundamental for ovulatory follicle rupture. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baumgarten SC, Armouti M, Ko C, Stocco C. IGF1R expression in ovarian granulosa cells is essential for steroidogenesis, follicle survival, and fertility in female mice. Endocrinology. 2017;158(7):2309–2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takarada T, Hinoi E, Nakazato R, Ochi H, Xu C, Tsuchikane A, Takeda S, Karsenty G, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Yoneda Y. An analysis of skeletal development in osteoblast-specific and chondrocyte-specific runt-related transcription factor-2 (Runx2) knockout mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(10):2064–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jo M, Gieske MC, Payne CE, Wheeler-Price SE, Gieske JB, Ignatius IV, Curry TE Jr, Ko C. Development and application of a rat ovarian gene expression database. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):5384–5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park JY, Jang H, Curry TE, Sakamoto A, Jo M. Prostate androgen-regulated mucin-like protein 1: a novel regulator of progesterone metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27(11):1871–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Na G, Bridges PJ, Koo Y, Ko C. Role of hypoxia in the regulation of periovulatory EDN2 expression in the mouse. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86(6):310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palanisamy GS, Cheon YP, Kim J, Kannan A, Li Q, Sato M, Mantena SR, Sitruk-Ware RL, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. A novel pathway involving progesterone receptor, endothelin-2, and endothelin receptor B controls ovulation in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(11):2784–2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang H, Ma WG, Tejada L, Zhang H, Morrow JD, Das SK, Dey SK. Rescue of female infertility from the loss of cyclooxygenase-2 by compensatory up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-1 is a function of genetic makeup. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):10649–10658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meek RL, Eriksen N, Benditt EP. Murine serum amyloid A3 is a high density apolipoprotein and is secreted by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(17):7949–7952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCoy MG, Sun GS, Marchadier D, Maugeais C, Glick JM, Rader DJ. Characterization of the lipolytic activity of endothelial lipase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(6):921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S. Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(5):671–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zaidi J, Jurkovic D, Campbell S, Collins W, McGregor A, Tan SL. Luteinized unruptured follicle: morphology, endocrine function and blood flow changes during the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(1):44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hinney B, Henze C, Kuhn W, Wuttke W. The corpus luteum insufficiency: a multifactorial disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(2):565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ko C, Gieske MC, Al-Alem L, Hahn Y, Su W, Gong MC, Iglarz M, Koo Y. Endothelin-2 in ovarian follicle rupture. Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):1770–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Migone FF, Cowan RG, Williams RM, Gorse KJ, Zipfel WR, Quirk SM. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role of vasoconstriction in rupture of the ovarian follicle at ovulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(8):2294–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cacioppo JA, Oh SW, Kim HY, Cho J, Lin PC, Yanagisawa M, Ko C. Loss of function of endothelin-2 leads to reduced ovulation and CL formation. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang FP, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. Normal prenatal but arrested postnatal sexual development of luteinizing hormone receptor knockout (LuRKO) mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(1):172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hsieh M, Johnson MA, Greenberg NM, Richards JS. Regulated expression of Wnts and Frizzleds at specific stages of follicular development in the rodent ovary. Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):898–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hsieh M, Mulders SM, Friis RR, Dharmarajan A, Richards JS. Expression and localization of secreted frizzled-related protein-4 in the rodent ovary: evidence for selective up-regulation in luteinized granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144(10):4597–4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hsieh M, Boerboom D, Shimada M, Lo Y, Parlow AF, Luhmann UF, Berger W, Richards JS. Mice null for Frizzled4 (Fzd4-/-) are infertile and exhibit impaired corpora lutea formation and function. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(6):1135–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Choi H, Ignacio RMC, Lee ES, Roby KF, Terranova PF, Son DS. Localization of serum amyloid A3 in the mouse ovary. Immune Netw. 2017;17(4):261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strauss JG, Hayn M, Zechner R, Levak-Frank S, Frank S. Fatty acids liberated from high-density lipoprotein phospholipids by endothelial-derived lipase are incorporated into lipids in HepG2 cells. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 3):981–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ishida T, Choi S, Kundu RK, Hirata K, Rubin EM, Cooper AD, Quertermous T. Endothelial lipase is a major determinant of HDL level. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(3):347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yancey PG, Kawashiri MA, Moore R, Glick JM, Williams DL, Connelly MA, Rader DJ, Rothblat GH. In vivo modulation of HDL phospholipid has opposing effects on SR-BI- and ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(2):337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Segi E, Tsuboi K, Aze Y, Nishimura T, Oida H, Yoshida N, Tanaka T, Katsuyama M, Hasumoto K, Murata T, Hirata M, Ushikubi F, Negishi M, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S. Failure of parturition in mice lacking the prostaglandin F receptor. Science. 1997;277(5326):681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.