Abstract

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are a prominent payment and delivery model, often described and promoted as provider-driven organizations. However, because of the flexible nature of ACO contracts, management organizations may also become partners in ACOs. We use data from the National Survey of ACOs (N=276) to understand the prevalence of non-provider management partners’ involvement in ACOs, the services these partners provide, and the structure of ACOs with such partners. We find that 37% of ACOs reported having a management partner, and two-thirds of these reported that the partner shared financial risk or reward. Among ACOs with partners, ACOs reported that 94% provided data services, 66% care coordination, 68% education, and 84% administrative services; half received all four services from their partner. ACOs with partners were smaller and more primary care focused than other ACOs. Performance and cost and quality was similar between ACOs with and without partners. Our findings suggest that management partners play a central role in many ACOs, perhaps providing smaller or physician-run ACOs with capital and expertise perceived as necessary to launch an ACO. However, further research is needed to understand the nature of these relationships including both positive aspects (e.g. enabling participation) and negative aspects (e.g. value extracted compared to delivered).

INTRODUCTION

From the outset, proponents of accountable care organizations (ACOs) hoped to make them provider-driven – encouraging physicians and other health care providers to take the reins to redesign care, provide high-value services, and drive quality and cost performance.(1,2) However, not all physicians and health care providers have the capacity to take on these goals alone: high startup costs of ACOs, limited experience with population health strategies such as care management, and improving, but inadequate, data analytic capabilities are among the many barriers to provider participation in ACOs.(3–7) Providers lacking necessary resources may turn to partners to provide various services and capabilities.(3,7,8) Some research has detailed the partnership activity between provider organizations,(7) but this literature does not speak to the involvement of non-provider management organizations in ACOs.

Observers of the first Medicare ACOs in 2012 were surprised to see that one-third of the original 27 Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs consisted of partnerships between Collaborative Health Systems (a subsidiary of Universal American, an insurance company) and groups of health care providers.(9,10) Subsequently, numerous additional non-provider organizations aligned with ACOs, including national organizations such as Valence Health, Walgreens, and Caravan Health, and organizations working in particular states or regions, such as Florida Accountable Care Services or MedChi. Despite some attention in the popular press and grey literature, scholarly work on ACOs has largely been silent on this activity.

To date, no research has empirically examined the extent to which management partners are involved in ACOs or the nature of relationships between ACO physicians and management organizations. Specifically, stakeholders need to understand the extent of management partner involvement in ACOs; the nature of these relationships; and how and why these relationships are forming to better consider the implications for US health care. For example, policymakers may be interested in the extent to which the services provided by management partners are associated with differences in ACO performance. In this paper, we focus on a primary question: To what extent have health care providers partnered with non-provider management entities in forming ACOs? We also begin to examine the nature of relationships between providers and managemnet partners by examining what services partners are providing to ACOs and how ACOs with these partners compare to other ACOs. Our goal is to provide the first look at this phenomenon, potentially paving the way for more in-depth examination of how these relationships might affect ACO performance.

METHODS

We learned about management partners through qualitative research on ACOs presented in other studies,(7,11–13) which served as formative interviews for this study and our cross-sectional survey data that constitute our results. In those formative phone interviews, we asked respondents about the organizations participating in their ACOs, how the ACOs formed, and the relationships among participating organizations. Several respondents discussed the involvement of non-provider organizations in their ACOs. For example, one ACO described working with a private company as a management partner to pursue an ACO. The partner instigated the ACO by developing a general ACO strategy and then recruiting physicians in the local area to pursue an ACO contract in partnership with the firm. The partner employed the ACO’s director as well as new ACO care coordinators who followed up with high-risk patients. The management partner also provided telephonic care management services to patients; visited physician practices to train staff and clinicians about the ACO model; and worked on reporting and compliance.

Another example informing our work came from a published case study on a safety net ACO.(14) In this ACO, we noted that the management partner (Optum) took on financial risk for ACO investments, including hiring a program director and performance improvement coaches for clinics, as well as investing in information technology infrastructure. The partner also worked with the ACO to develop their care delivery model and provide administrative services.

Based on this information, we identified a need to collect representative, systematic data on the prevalence and roles of management partners in ACOs. We aimed for national data from a wide set of ACOs. We opted to add relevant questions about arrangements that ACOs had with management partners to Waves 2 and 3 of the National Survey of ACOs (NSACO).(7,15) Survey questions are available in the appendix.(16) The NSACO captured comprehensive data on ACO organization, leadership, provider composition, capabilities, and initiatives. Each wave surveyed the full population of ACOs (including ACOs participating in Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payer ACO contracts and programs) formed during a given time period, and the waves do not form panel data (i.e., ACOs in wave 3 are a new set of ACOs, not the same ones surveyed in Wave 2). The respondent at each organization is typically a member of senior leadership, such as the CEO, CMO, President, or ACO Director. Waves 2 and 3 were fielded 2013–2015; the survey response rate was 58%. Results from prior analyses show no evidence of non-response bias.(15,17) We use data on ACO performance from publicly available files on Medicare ACO performance.(18)

A yes/no survey question asked, “Is your ACO affiliated with a third-party administrator or external, non-provider partner organization (e.g., management services organization or administrative services partner)?” (Yes/No). We included follow up questions for ACOs with partners to understand the partners’ role. These questions include whether the partner shared in risk and/or reward, as well as information on a set of services the partner provided. The services were yes/no questions, asking if the partner provided data services (e.g., processing payer data, generating reports, or software development); care coordination (e.g., operating a nurse call line or overseeing clinic performance coaches); education (e.g., educating clinicians on new payment models and quality measures); and administrative services (e.g., writing up the ACO contract, receiving and distributing savings, or convening meetings and committees).

We examined descriptive statistics on these questions, and compared ACOs with and without a partner on several dimensions, including the provider composition of the ACO, and services the ACO offers. Among Medicare ACOs, we also compared ACOs with and without partners on performance on cost savings and overall quality performance in years 1 and 2. We also examined if ACOs receiving more services from a management partner or ACOs receiving financial support experienced greater savings or scored higher on the quality metrics.

LIMITATIONS

Our analysis has some limitations. First, our survey question was deliberately broader than most survey questions because we were aiming to collect data on phenomena that had not been previously examined. We expected a continuum of arrangements between ACOs and other firms, ranging from firms with a purely vendor relationship with an ACO to firms that initiated ACOs by recruiting providers to form them. We crafted a question that we anticipated would accurately identify partners and filter out vendor relationships. After answering this question, ACOs were asked to write in the name of the partner. We found the data provided in this written in question had face validity; for example, ACOs with popularly known partners identified those partners in this field. (Due to survey confidentiality, we cannot state names of partners that may identify survey respondents). Second, our analysis can provide only limited information on the nature of partnerships with non-provider partners from our survey questions.

RESULTS

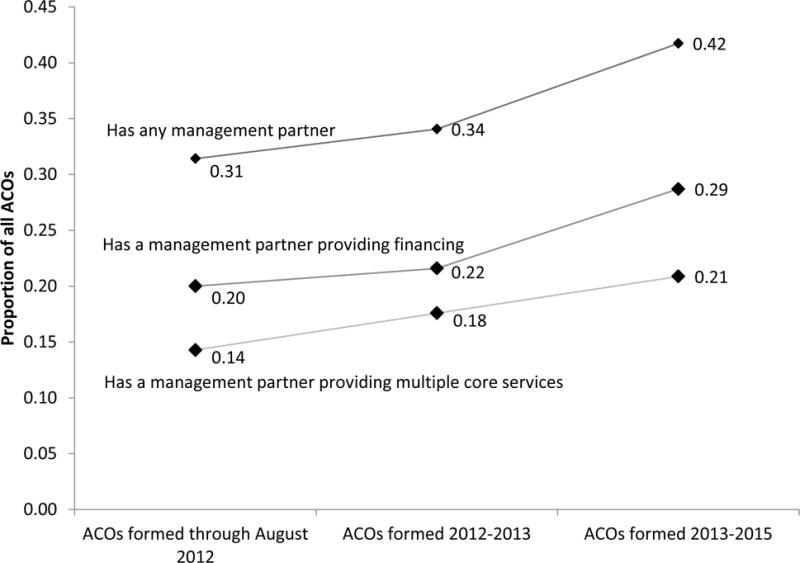

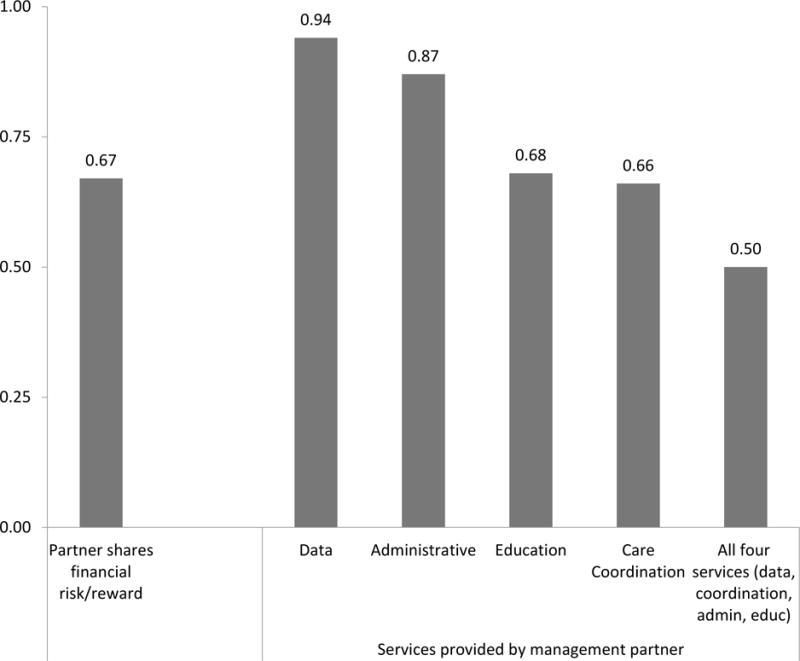

A total of 37% of ACOs in our survey data reported having a management partner in their ACO (Exhibit 1). Across waves of ACOs, the percent rises from 31% in ACOs formed through August 2012, to 34% in ACOs formed 2012–13, to 41% in ACOs formed 2013–15 (χ2=2.4, p=0.30). Two thirds of those with partners reported that the partner shared in financial risk and/or reward (Exhibit 2). Among those with management partners, 94% of ACOs report the partner providing data services, 66% care coordination, 68% education, and 84% administrative services. Among ACOs with management partners, 50% reported their partner provided all four of these services to the ACO, suggesting that in these ACOs the partners may play an influential or powerful role in ACO operations.

Exhibit 1.

Proportion of ACOs with management partners increased across ACO cohorts, as did share of ACOs with a management partner providing financing or multiple core services

Source: Authors’ analysis of National Survey of ACOs, Waves 1–3

Notes: “Multiple core services” means the management partner is providing all four services described in the text and Exhibit 2, including data analytics, care coordination, administrative services, and provider education.

Exhibit 2.

Prevalence of financing and services from management partners among ACOs with management partners

Source: Authors calculations

Notes: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ***p<0.001

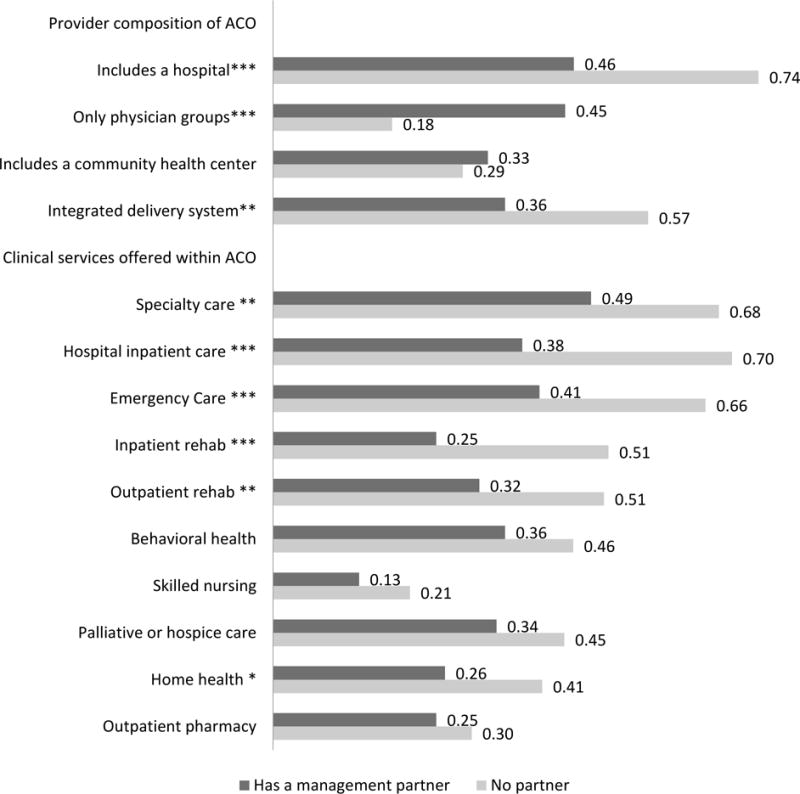

Among ACOs with a management partner (Exhibit 3), many fewer included a hospital (0.48 vs 0.70, p<0.001) or an integrated delivery system (0.38 vs. 0.57, p<0.01), and ACOs with a partner were more likely to be composed of only physician groups (0.40 vs 0.18, p<0.001). ACOs with a partner also have a higher proportion of primary care physicians (0.68 vs 0.55, p<0.05). ACOs with a partner in general were less likely to offer a spectrum of services outside of primary care (Exhibit 3), reporting lower rates of inclusion of specialty care, hospital inpatient care, emergency care, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, and home health. Finally, ACOs with a partner were less likely to have a commercial payer ACO contract (0.48 vs. 0.70, p<0.001) and more likely to have a Medicare contract (0.84 vs. 0.70, p<0.05) (See appendix).(16)

Exhibit 3.

Provider composition and clinical services offered in ACOs with and without management partners show ACOs with management partners are smaller and more primary care centered

Source: authors’ analysis of the National Survey of ACOs, Waves 1–3

Notes: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ***p<0.001

ACO performance in Medicare did not differ significantly among ACOs with and without partners (Exhibit 4). A similar proportion of ACOs with and without partners achieved savings in both first and second years of ACO contracts. ACOs with and without partners also achieved very similar quality composite scores in both years. We also compared ACOs with partners that provided all four services compared to ACOs with partners that provided fewer services, and ACOs with partners that provided financial support compared to ACOs with partners that did not provide financial support. There were no significant differences in cost or quality performance across these types of management partners.

Exhibit 4.

Performance among Medicare ACOs with and without management partners

| Includes Partner | No Partner | p-value on difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost performance | |||

| Achieved savings in year 1 | 23% | 17% | n/s |

| Achieved savings in year 2 | 23% | 25% | n/s |

| Gross savings per beneficiary in year 1 | $72 ($72) | $6 ($52) | n/s |

| Gross savings per beneficiary in year 2 | $117 ($69) | $27 ($71) | n/s |

| Quality composite score(out of 100 possible points) | |||

| Year 1 mean score | 63 | 64 | n/s |

| Year 2 mean score | 67 | 68 | n/s |

| N | 56 | 92 |

Source: authors’ analysis of the National Survey of ACOs, Waves 1–3

n/s not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

DISCUSSION

Management partners play a significant role in ACOs. More than one-third of ACOs were working with a management partner, and these ACOs were on average more heavily primary care and outpatient care focused. ACOs that had a management partner were less likely to include hospitals and be integrated delivery systems, more likely to include only physician groups, and less likely to provide an array of services within the ACO. Management partners provide a variety of services to ACOs, and among half of ACOs, the management partners play a central role in ACO operations. Our data show that a number of different types of organizations are playing the management partner role, including pre-existing management services organizations; consulting firms, including large pre-existing firms and small boutique firms formed solely to work with ACOs; commercial health plans or health plan subsidiary companies; and non-profit consortiums.

What do these results mean to the ACO movement or the future of ACOs, and the physicians involved in ACOs? ACOs with partners have quality and cost performance on par with ACOs that have no partner, giving no clear indication of whether management partners intrinsically improve providers’ ability to meet quality or cost performance targets. Our results do suggest that outpatient, physician-based ACOs are considerably more likely to work with a management partner. It is possible that management partners are helping more physician groups to participate in ACO programs than would otherwise occur, perhaps lending some credence to the phrase used in industry of management partners serving as “ACO enablers.” It is unclear how this relates to broader findings on better performance among physician-run ACOs, however.(19) For example, our sample was too small to tease apart performance between physician group ACOs with and without a partner, and our study design does not allow us to examine a counterfactual scenario examining how ACOs who have a partner may have performed without a partner (or vice versa: how ACOs without a partner may have performed with such a partner). Thus, the selection issues inherent in our performance comparisons limit our confidence in speaking to what value partners bring to the providers they work with.

Several other considerations warrant attention. First, much has been made of the capital and expertise necessary to begin an ACO, with some observers detailing expensive start-up costs.(3–5) Our data suggest that many ACOs are relying on management partners for financial support, including start-up funding. This may be particularly true for ACOs without hospitals, given literature which shows that in ACOs with hospitals, the hospital often brings financing and technical capabilities to the ACO.(3) ACOs’ relationships with management partners may be similar to relationships between management services organizations and integrated delivery networks or physicians, where the management partner offers a set of centralized services and manages the contract,(20,21) as well as takes a cut of the savings or bonuses achieved by the ACO.

This arrangement has both positive and negative aspects. In some ways, these relationships between physician networks and management partners may resemble relationships between physician networks and insurers partnering to start provider-sponsored health insurance plans, through Medicare Advantage or other domains. Policymakers and payers may want to consider potential problems with such relationships between management partners and ACOs. In particular, understanding how savings are shared between physicians and partners may be important. For example, some observers argued that fees levied by practice management firms have been high in relation to the value of the service provided for physician groups.(20) Based on such experience, it is possible that inexperienced providers would benefit from protection or guidance in contracting with management partners, particularly given the unregulated and new realm of non-provider partners with ACOs, to ensure providers contract in their best interest.

Second, it is possible in some cases that the management partner is playing a central role in developing physician networks to pursue ACO contracts. Our data suggest that in around half of ACOs with a management partner, the partner is providing four key services, and in two-thirds of those ACOs, the partner provided financing. This indicates that the partner is a major driver (or perhaps the major driver) instigating ACO activity among providers. More data are needed to understand the extent to which this is the case. In these cases, management partners are likely engaging physicians in ACO activity whom otherwise would not be participating in ACOs.

Our data suggest that policy-makers, at both the state and federal levels, as well as payers, should take into account the roles of management partners in ACOs. Providers’ needs for capital and technical expertise are still unmet. Medicare has sought to meet needs for capital through Advance Payment Program and the ACO Investment Model, but not all ACOs qualify for these programs. Additional up-front funding for providers may allow those with limited assets to effectively start an ACO without searching for a partner to provide significant funding for infrastructure, such as data analytics or staff for care management.

Needs for technical expertise or data infrastructure similarly could be provided through payers, such as states, Medicare, or commercial payers. For example, incentives might be used to support smaller physician groups and those in rural areas lacking the resources for needed management and infrastructure capabilities. Or, states, Medicare, or other payers may choose to support providers further with more centralized or expert data analytics, as Blue Cross has done in the Alternative Quality Contract in Massachusetts and some payers are doing through commercial payer ACO programs. Similarly, the state of Colorado through their Medicaid program has developed dashboards for providers, providing a data analytic tool centrally such that physician groups need not purchase or develop this capacity internally.

An additional question for consideration is how the prevalence of management partners in ACOs may influence some of the less proximal outcomes of ACOs. ACOs are sometimes considered one step in a larger progression toward population health and value-based purchasing, allowing providers to gain experience in population health before transitioning to a more global model. While some facets of management partners may be a time-limited need (e.g. financing to being ACO initiatives), other facets may reflect a long term set of resources partners are supplying, such as data analytic work or care management, and the interaction of provider reliance on partners and the longer arc of delivery reform should be considered. The presence of management partners at the ACO stage may facilitate providers contracting for expertise rather than building it internally, and this arrangement will have implications for the types of expertise and capabilities being built internally by provider groups. Providers that rely heavily on management partners in ACO contracts may require similar assistance or partnerships in more advanced value-based contracts or population health programs, building in a role for management organizations that is much longer-term than ACO contracts.

There are several avenues where additional research would significantly advance our understanding of management partnerships in ACOs. A richer understanding of the nature of these partnerships is necessary to assess their positive or negative consequences, if any. In particular, understanding the nature, motivation, and structure of relationships between providers and management organizations is essential to building better policy. For example, are providers looking to partners for capital investment, for expertise, or to provide services difficult for providers to develop internally? To what extent are providers seeking out partners, versus partners seeking out providers? What are the financial relationships between providers and partners? To what extent is this activity possibly foreshadowing changes in the organization of health care, such as consolidation or purchasing of health care providers by non-health care entities? While management partners may exert negative influences on an ACO’s autonomy, it is likely that without these partners there would be far fewer providers participating in ACOs in the United States today. It will be important to continue to track the development of management partners and their net impact on performance as ACOs continue to grow and evolve.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Valerie A. Lewis, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Thomas D’Aunno, Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University, New York City, New York.

Genevra F. Murray, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire

Stephen M. Shortell, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California.

Carrie H. Colla, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

References

- 1.Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JPW, Gottlieb DJ. Creating Accountable Care Organizations: The Extended Hospital Medical Staff. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Jan 1;26(1):44–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClellan MB, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A National Strategy to put Accountable Care into Practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 May;29(5):982–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Tierney E, Muhlestein DB. Hospitals Participating In ACOs Tend To Be Large And Urban, Allowing Access To Capital And Data. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2016 Mar 1;35(3):431–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Association of ACOs. First National ACO Survey on Startup Costs [Internet] 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/first-national-aco-survey-on-startup-costs-242177361.html.

- 5.Moore KD, Coddington DC. The Work Ahead: Activities and Costs to Develop and Accountable Care Organization. Washington, D.C.: American Hospital Association; 2011. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shortell SM, McClellan SR, Ramsay PP, Casalino LP, Ryan AM, Copeland KR. Physician practice participation in accountable care organizations: the emergence of the unicorn. Health Serv Res. 2014 Oct;49(5):1519–36. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis VA, Tierney KI, Colla CH, Shortell SM. The new frontier of strategic alliances in health care: New partnerships under accountable care organizations. Soc Sci Med [Internet] 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.054. [cited 2017 May 16]; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617302939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Burke GC, Brundage SC. Accountable Care in New York State: Emerging Themes and Issues [Internet] New York, NY: United Hospital Fund; 2015. Apr, Available from: https://nyshealthfoundation.org/uploads/resources/accountable-care-in-new-york-emerging-themes-and-issues.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manos D. CHS is partnered with third of new Shared Savings ACOs [Internet] Healthcare IT News. 2012 [cited 2017 May 23]. Available from: http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/chs-partnered-third-new-shared-savings-acos.

- 10.Evans M. Doc-led ACOs seek to manage costs, quality and hospital relationships [Internet] Modern Healthcare. 2012 [cited 2017 May 23]. Available from: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20120414/MAGAZINE/304149950. [PubMed]

- 11.Lewis VA, Colla CH, Schoenherr KE, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Innovation in the safety net: integrating community health centers through accountable care. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Nov;29(11):1484–90. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis VA, Colla CH, Tierney K, Citters ADV, Fisher ES, Meara E. Few ACOs Pursue Innovative Models That Integrate Care For Mental Illness And Substance Abuse With Primary Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014 Oct 1;33(10):1808–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis VA, Schoenherr K, Fraze T, Cunningham A. Clinical coordination in accountable care organizations: A qualitative study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016 Dec 6; doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenherr KE, Van Citters AD, Carluzzo KL, Bergquist S, Fisher ES, Lewis VA. Establishing a Coalition to Pursue Accountable Care in the Safety Net: A Case Study of the FQHC Urban Health Network [Internet] New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2013. Oct, [cited 2014 Feb 28]. Report No.: 1710. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Case-Studies/2013/Oct/Coalition-to-Pursue-Accountable-Care-in-the-Safety-Net.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. First National Survey Of ACOs Finds Physicians Are Playing Strong Leadership And Ownership Roles. Health Aff Millwood. 2014 Jun;33(6):964–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article box online.

- 17.Albright BB, Lewis VA, Ross JS, Colla CH. Preventive Care Quality of Medicare Accountable Care Organizations: Associations of Organizational Characteristics With Performance. Med Care. 2016 Mar;54(3):326–35. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014 Shared Savings Program (SSP) Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) PUF [Internet] Data.CMS.gov. [cited 2016 May 9]. Available from: https://data.cms.gov/Public-Use-Files/2014-Shared-Savings-Program-SSP-Accountable-Care-O/888h-akbg.

- 19.McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 13;0(0) doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1600142. null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns LR, Goldsmith JC, Sen A. Horizontal and vertical integration of physicians: a tale of two tails. Adv Health Care Manag. 2013;15:39–117. doi: 10.1108/s1474-8231(2013)0000015009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns LR, Muller RW. Hospital-Physician Collaboration: Landscape of Economic Integration and Impact on Clinical Integration. Milbank Q. 2008 Sep 1;86(3):375–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.