Abstract

Purpose

Information on vaccine utilization from a variety of sources is useful to give a status of the vaccine program and define opportunities to improve uptake. We evaluated MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation and completion of all three doses among girls/women from 2006 to 2012.

Methods

Data were obtained from the 2006–2012 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database. The study population included female enrollees aged 11–26 years who were continuously enrolled in the same private insurance plan from 2006 to 2012 (n = 407,371). We evaluated overall and yearly vaccine initiation and completion, demographic characteristics associated with vaccine initiation, clinical visits in which vaccine was given, and missed opportunities for vaccination.

Results

By the end of 2012, 36.9% of females aged 11–26 years had received at least one HPV vaccine dose. Vaccination coverage was highest among females aged 17–18 years (49.3%) and aged 15–16 years (43.1%) and lowest among females aged 11–12 years (16.8%). Between 2007 and 2012, 96.1% of the 246,192 unvaccinated females had at least one missed opportunity (a heath care visit without HPV vaccine administered).

Conclusions

Over a 6 year period, HPV vaccine initiation was lowest in the girls aged 11–12 years. Importantly, most (96.1%) unvaccinated females had at least one missed vaccination opportunity, and providers and health systems should focus efforts on using existing visits for vaccination.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, Administrative data, Vaccine coverage, Missed opportunities for vaccination

Two human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are licensed and recommended for use in the United States—the bivalent HPV vaccine and the quadrivalent HPV vaccine. Either vaccine is recommended for routine use in girls aged 11 or 12 years; vaccination is also recommended through age 26 years for girls and young women who did not receive or complete the vaccine series [1,2]. In 2011, quadrivalent HPV vaccine was recommended for routine use in boys aged 11 or 12 years; and vaccination is also recommended through age 21 years for boys and young men who did not receive or complete the vaccine series [3]. These vaccines offer an opportunity to reduce the burden of cervical cancer and other important cancers including oropharyngeal and anal cancers in males and females, vaginal and vulvar cancers in females, and penile cancers in males.

Information on vaccine utilization from a variety of sources is useful to provide a status of the vaccine program and define opportunities to improve uptake. One of the best measures of vaccine utilization in adolescents is from the National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) which provides vaccine uptake in 13- to 17-year-olds each year [4]. Information from 2010 found that one-dose HPV uptake was 49% and three-dose uptake was 32% [4], and there were no increases in 2011 and 2012 with three-dose uptake of 33.4% [5,6]; in 2013, three-dose uptake rose modestly to 37.4% [7]. However, NIS does not provide information on vaccine utilization in older teens and young adults. Data from the National Health Interview Survey in 2010 found 28.9% of 11- to 17- year-olds had initiated vaccine [8], and in 2008,11.7% of women aged 18–26 years reported receiving at least one dose of the HPV vaccine [9]. Vaccine initiation decreased with increasing age >18 years, and 7.9% of females aged 21–26 years had ever had vaccine [9].

Few assessments of HPV vaccine coverage have evaluated birth cohorts of adolescent girls and young women. Birth cohorts offer the advantage of monitoring uptake in the same population over time. In addition, specific factors relevant to vaccine utilization and missed opportunities in an insured population are also important to highlight. Data from MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database are especially useful to assess vaccine coverage in a large number of females with a wide range of ages. In this report, we provide information on HPV vaccine initiation and completion of all three doses from more than 400,000 females continuously enrolled in the same private insurance plan from 2006 to 2012 in MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database [10].

Methods

Data source

Data were obtained from the 2006–2012 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database [10]. The Database contains information from more than 40 large employers, health plans, and government and public organizations on insured individuals. All states including Washington, D.C. are represented. More than 27 million females aged ≤64 years (20.1% of estimated 2012 U.S. females aged 0–64 years) were represented in the database during 2012. The databases contain patient-level variables including: demographics, dates of services for outpatient and hospital visits, diagnostic codes (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]), procedure codes (Physicians’ Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition [CPT4]), and payment data. Provider characteristics, type of provider, and insurance category are also included. Pediatrician, family practitioner (FP), internal medicine, and obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/Gyn) are classified separately as primary care providers for this analysis; all other medical categories are classified as specialists or subspecialists (e.g., cardiologists, allergists, and sports medicine).

Study population

The study population included all female enrollees with birth year between 1986 and 2001 who were continuously enrolled in the same insurance plan from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2012 (n = 407,371). This study population is 6% of the 2012 MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters female population with birth year between 1986 and 2001. Females in the 6-year cohort were grouped into five categories based on their age as of December 31, 2012 as follows: 11–12 years old (born in 2000–2001); 13–14 years old (born in 1998–1999); 15–16 years old (born in 1996–1997); 17–18 years old (born in 1994–1995); and 19–26 years old (born in 1986–1993).

This study was reviewed by the human subjects coordinator at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases; and as an analysis of secondary data, without identifiers, was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review.

Data analysis

Data analysis was limited to females as the HPV vaccine was routinely recommended only for females during most of the study period. Receipt of the first dose of HPV and all three doses of the vaccine series was assessed by age group, region, metropolitan statistical area (MSA), and type of insurance plans. Health insurance plans were categorized as three types—fee-for-service plans, including basic/major medical (no observations in this category in our sample) and comprehensive; managed care plans, including exclusive provider organization, health maintenance organization, noncapitated point-of-service (non-capitated POS), preferred provider organization, and capitated or partially capitated point-of-service (capitated POS); and high-deductible plans, including consumer driven health plans and high-deductible health plans. Of the managed care plans, health maintenance organization and capitated POS plans were considered capitated plans.

For each dose of HPV vaccine received, the type of visit (mutually exclusive categories: sick visit, preventive visit, and vaccine-only visit) during which the vaccine was administered was determined. Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set [11] definitions were used to identify preventive care visits, which included the following ICD-9 codes: V20.2, V70.0, V70.3, V70.5, V70.6, V70.8, and V70.9 in primary diagnosis codes, and any CPT codes with 99381–99397. Vaccination-only visits were visits where only vaccinations were given. Sick visits were non-preventive visits where any numeric ICD-9 codes and E-codes were in the diagnosis codes of the claims.

Among females who initiated the HPV vaccine series, the type of provider (pediatrician, FP, internal medicine, OB/Gyn, or other) administering the first dose was determined. Additionally, simultaneous vaccination (i.e., same day administration of HPV vaccine and one or more other vaccines) was assessed. The other administered vaccines included influenza; tetanus and diphtheria toxoids adsorbed (Td); tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine adsorbed (Tdap); measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR); hepatitis B vaccine (Hep B); varicella vaccine (Var); quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4); and quadrivalent meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4).

Among females who did not initiate the HPV series, missed vaccination opportunities were assessed. A missed opportunity was defined as a health care visit for any reason occurring between 2007 and 2012 where the HPV vaccine was indicated but not administered. Because HPV vaccination is not recommended for pregnant women, we excluded pregnancy related visits from analysis. We assumed providers would likely not administer the vaccine before the age of 11 years; therefore, health care visits occurring before the age of 11 years were excluded. Females with at least one missed opportunity were further classified into two mutually exclusive groups: at least one missed opportunity occurred during a visit where another vaccination was administered or all missed opportunities occurred during health care visits where no vaccine was administered.

Analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Vaccination

By the end of 2012, 36.9% of females had received at least one HPV vaccine dose (Table 1). Vaccine initiation was highest among females aged 17–18 years (49.3%) and 15–16 years (43.1%) and lowest among females aged 11–12 years (16.8%). Overall and by birth cohort, vaccine initiation was highest among females with employer self-insured health plans, living in the northeast, and living in an MSA. Vaccine initiation also varied by insurance types. Females enrolled in managed care plans (37.1%) had HPV vaccination similar to those with high-deductible plans (37.3%); HPV vaccination with either of these types of insurance was higher than that of fee-for-service plans (30.4%). Completion of vaccination s was 21.9%; vaccination coverage for three doses followed the same pattern as vaccine initiation by employer self-insured health plan, region, MSA, and insurance types (data not shown).

Table 1.

Estimated vaccination coverage of ≥1 human papillomavirus vaccine dose among females aged 11–26 years by selected characteristics, 2006–2012

| Age (years)a in 2012 | Total (N = 407,371); % vaccinated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 11–12 (N = 50,766); % vaccinated | 13–14 (N = 55,283); % vaccinated | 15–16 (N = 59,757); % vaccinated | 17–18 (N = 64,767); % vaccinated | 19–26 (N = 176,798); % vaccinated | ||

| Whole sample (N = 407,371) | 16.8 | 32.3 | 43.1 | 49.3 | 37.1 | 36.9 |

| Employer self-insured health plans | ||||||

| Yes (N = 364,330) | 17.2 | 33.0 | 44.2 | 51.3 | 39.5 | 38.7 |

| No (N = 43,041) | 13.7 | 26.0 | 33.5 | 39.0 | 29.1 | 29.4 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast (N = 44,659) | 15.2 | 35.6 | 52.8 | 62.7 | 55.2 | 50.4 |

| North Central (N = 87,814) | 18.2 | 32.1 | 42.5 | 48.3 | 29.9 | 32.4 |

| South (N = 159,354) | 15.7 | 29.5 | 38.8 | 43.9 | 32.9 | 33.1 |

| West (N = 115,544) | 18.6 | 33.8 | 42.2 | 49.0 | 36.0 | 36.4 |

| Metropolitan statistical area | ||||||

| Yes (N = 351,947) | 16.9 | 32.7 | 44.1 | 50.7 | 38.1 | 37.8 |

| No (N = 55,423) | 16.6 | 29.1 | 36.3 | 40.7 | 29.3 | 30.4 |

| Insurance Type | ||||||

| Fee-for-service (N = 6,481) | 16.2 | 21.7 | 30.2 | 34.5 | 32.8 | 30.4 |

| Managed care (N = 348,705) | 16.9 | 32.5 | 43.1 | 49.2 | 37.3 | 37.1 |

| High-deductible (N = 48,663) | 16.6 | 32.0 | 44.9 | 52.6 | 37.0 | 37.3 |

Age as of Dec 31, 2012; 11–12 year cohort was born 2000–2001; 13–14 year cohort was born 1998–1999; 15–16 year cohort was born 1996–1997; 17–18 year cohort was born 1994–1995; 19–26 year cohort was born 1986–1993.

Cumulative coverage with one or more doses of HPV vaccine by the end of 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012 by birth cohort is demonstrated in Table 2. Coverage at ages 11–12 years was 13.8% in 2008, 12.9% in 2010, and 16.8% in 2012; coverage at ages 14–21 years was 27.3% in 2008, 29.0% in 2010, 32.3% in 2012; and coverage at ages 15–16 years was 39.4% in 2010 and 43.1% in 2012.

Table 2.

Cumulative vaccination coverage of ≥1 human papillomavirus vaccine dose among females aged 11–26 years, 2006–2012

| Cohort, Age in year 2012 (N)a | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | % Increase (2008–2007) | % Increase (2009–2008) | % Increase (2010–2009) | % Increase (2011–2010) | % Increase (2012–2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| % Vaccination coverage | ≥1 HPV dose | ||||||||||

| Cohort 1, 11–12 (50,766) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.5 |

| Cohort 2, 13–14 (55,283) | NA | NA | NA | 12.9 | 22.9 | 32.3 | NA | NA | NA | 10.1 | 9.3 |

| Cohort 3, 15–16 (59,757) | NA | 13.8 | 22.2 | 29.0 | 36.6 | 43.1 | NA | 8.4 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 6.5 |

| Cohort 4, 17–18 (64,767) | 16.4 | 27.3 | 34.3 | 39.4 | 44.4 | 49.3 | 10.9 | 7.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

| Cohort 5, 19–26 (176,798) | 16.1 | 25.7 | 30.6 | 33.6 | 35.4 | 37.1 | 9.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Total (407,371) | 12.2 | 20.1 | 25.1 | 29.0 | 32.8 | 36.9 | 7.9 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.1 |

Same ages represented by: bold, 11–12 years; underlined, 13–14; and bold/underlined, 15–16 years.

NA = not applicable.

Age as of Dec 31, 2012; 11–12 year cohort was born 2000–2001; 13–14 year cohort was born 1998–1999; 15–16 year cohort was born 1996–1997; 17–18 year cohort was born 1994–1995; 19–26 year cohort was born 1986–1993.

Health care utilization

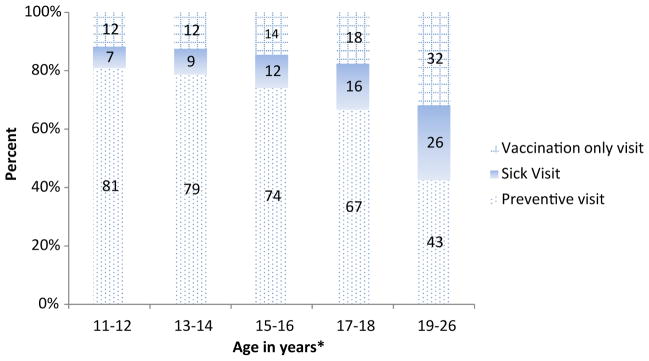

With the exception of the oldest cohort, the first dose of HPV vaccine was most frequently administered during a preventive health care visit (Figure 1). The proportion of females initiating the series at either a vaccination-only visit or sick visit increased with age. Administration of the second or third dose of HPV followed a different pattern; consistently across the cohorts, about two-thirds of females received these doses at vaccination-only visits and 20.1% received the doses during a preventive health care visit (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Type of visit at which first dose of HPV vaccine was administered by age, among females receiving ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine, 2006–2012. *Percentages may not total to 100% due to rounding. *Age as of Dec 31, 2012; 11–12 year cohort was born 2000–2001; 13–14 year cohort was born 1998–1999; 15–16 year cohort was born 1996–1997; 17–18 year cohort was born 1994–1995; 19–26 year cohort was born 1986–1993.

The type of health care provider administering the first dose of the HPV series varied by cohort. The proportion of females receiving the first dose from a pediatrician was greatest among the cohort aged 13–14 years (62.8%) and decreased with increasing age. Conversely, the proportion of females receiving the first dose from an FP or OB/Gyn increased with age (data not shown).

Among females who received the first dose of HPV vaccine, 38.6% received an additional vaccine on the same day. Simultaneous vaccination was more common among the youngest cohort (cohort 1 that was born in 2000–2001: 78.8%) and was less common among the oldest cohort (cohort 5 that was born in 1986–1993: 26.8%) (data not shown).

A total of 246,192 unvaccinated females met the criteria for the missed opportunity analysis. Between 2007 and 2012, overall 96.1% of unvaccinated females had at least one missed opportunity to receive the HPV vaccine (Table 3). More than half of the unvaccinated females aged 13–18 years experienced at least one missed opportunity during a visit where another vaccine was administered (Table 3). Overall, unvaccinated females experienced a median of 13 visits with a missed opportunity to receive the HPV vaccine (5–95 percentiles: 1–76).

Table 3.

Percent of unvaccinated femalesa with at least one missed opportunity to receive the first dose of human papillomavirus vaccine by age, 2007–2012

| Age in years (N)b | Overall % females in age group with at least one missed opportunityc | % Females in age group with at least one missed opportunity occurring at a visit where a vaccine was administered | % Females in age group with at least one missed opportunity occurring at visit where no vaccines were administered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11–12d (42,186) | 87.3 | 45.4 | 42.0 |

| 13–14e (37,747) | 96.8 | 66.9 | 30.0 |

| 15–16 (34,735) | 98.2 | 71.9 | 26.4 |

| 17–18 (33,795) | 97.9 | 62.9 | 35.0 |

| 19–26 (97,729) | 97.1 | 33.4 | 63.7 |

| Total (246,192) | 96.1 | 44.3 | 51.8 |

Females were included in the analysis if they (1) had never received HPV vaccine; (2) made a health care visit during 2007–2012 (pregnancy related visits were excluded); and (3) were between the ages of 11 and 26 years at the time of the visit.

Age as of Dec 31, 2012.

Percentages in column 2 may be slightly different from the sum of percentages in column three and four due to rounding.

Only evaluated visits occurring in 2012.

Only evaluated visits occurring between 2010–2012.

Discussion

Our assessment of national level claims data including more than 400,000 privately insured females followed for 6 years identified that 36.9% of females aged 11–26 years had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine and 21.9% of females had received all three doses. Importantly, most (96.1%) unvaccinated females had at least one missed vaccination opportunity during a 6-year period.

Initiation and completion of HPV vaccine series have been a challenge in the United States with national vaccination surveys describing vaccine initiation of 57.3% and all three doses of 37.6% as of 2013 [7]. Compared with two other vaccines also recommended for adolescents in the United States, Tdap and MCV4 vaccines, HPV vaccine initiation and series completion are substantially lower. The coverage rates for Tdap and MenACWY in 2013 were 86% and 77.8%, respectively [12]. Our evaluation found lower vaccine initiation and completion than other published studies [4–7,13].

Our study is unique in that it evaluates a cohort of females continuously enrolled in a private health insurance plan for 6 years to assess increases of vaccination over time. Most studies of an insured population have included subjects continuously enrolled for 12 months [13] or 24 months [14] and estimated coverage at one point in time. One study evaluated adolescents from 2006 to 2011, and this study found 82% had a missed opportunity for HPV vaccination [15]. We found a similar pattern to that seen nationally among adolescent females aged 13–17 years where initiation increased 12.1% between 2007 and 2008, 7.1% between 2008 and 2009, 4.4% between 2009 and 2010 but did not increase in females between 2011 and 2012 [4,16].

A frequently cited barrier to adolescent vaccination is that adolescents do not make sufficient visits to their health care provider, thus providing limited opportunities to receive recommended vaccinations [17,18]. In our analysis, we had a long observation period so that many infrequent health care visitors could be captured. All cohorts except cohort 1 were observed for at least 3 years since they first reached the age of 11 or 12 years (the recommended age) during the 2007–2012 window. We found that 96.1% of the insured females who had never received HPV had at least one clinical visit which was a missed vaccination opportunity. Among females aged 13–18 years, more than half had at least one missed opportunity during a visit when other vaccines were administered. Our data do not provide information about whether the missed opportunity occurred because the health care provider did not offer or recommend the vaccine or because the parent/patient refused the vaccine. Collection of information on reasons the HPV vaccine was not given at each visit may be useful to inform strategies to optimize health care visits and improve vaccine delivery. A number of studies that have described provider and parent practices regarding HPV vaccine that may be informative regarding reasons for missed opportunities.

Several studies have shown that providers are less likely to strongly recommend the HPV vaccine to young adolescents [19–21] or use a risk-based approach to recommending the vaccine [22,23]. This is one reason why these health care visits may not be optimized for vaccination. Additionally, health care providers sometimes present the HPV vaccine differently emphasizing that it is optional compared with other recommended vaccines which may be required for school entry [22,24]. Parents/patients may interpret a weak or no recommendation as an indication that the vaccine is not necessary or important. Parents themselves may have concerns regarding the vaccine and may refuse vaccination of their daughters despite a provider’s best effort. According to the 2010 NIS-Teen, the parents of unvaccinated girls who indicated they had no intention of vaccinating their daughter with the HPV vaccine in the next 12 months most frequently cited the reasons that their daughter was not sexually active or the vaccine was not needed [16]. When confronted with parents who are reluctant to get the HPV vaccine for their daughter, providers may be hesitant to engage them in further discussion [24]. Systems approaches such as standing orders, reminders, or others within office settings may further support vaccination and reduce the burden on providers.

The continuous enrollment and private insurance coverage for our sample might lead to an expectation that this population would have higher vaccination coverage because of more stable health care access; therefore, it is notable to find lower vaccination compared with that of national estimates. In addition, insured females are found to have higher HPV vaccine uptake than uninsured females [25–27]. However, evidence varies on whether private insurance increases HPV coverage compared with public insurance. Although more studies show that private insurance is associated with higher HPV vaccine initiation [27–29], one study found Vaccine for Children (VFC)–eligible, insured girls (with public insurance) were more likely to initiate the HPV vaccination series than girls with private insurance [26].

It is expected that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 may have impact on the HPV vaccine coverage rates after 2010. There are two ways in which this law could play a role. First, ACA mandates new health insurance plans to cover recommended preventive care, including HPV vaccination, with no cost-sharing for patients at network providers. Thus, the financial barrier is removed for patients. Second, dependent children are allowed to stay under their parents’ health insurance through the age of 26 years [30]. Our findings are early but they did not show a substantial increase in HPV coverage after 2010; future assessments may further evaluate the impact of this law on vaccination coverage indirectly.

Our study is subject to several limitations. The MarketScan databases are based on insurance claims, and thus, reflect only insured populations attending outpatient visits and are not representative of the general population. Vaccination that occurred in other health care settings that did not go through the insurance claim process would not be included in our analysis, thus we may be underestimating vaccine coverage. Although our sample included females with health insurance, we did not have information on the covered services for each plan and lack of coverage for the HPV vaccine could influence receipt of the vaccine.

In conclusion, this evaluation of HPV vaccine initiation from a cohort of insured females found similar findings to other national evaluations of HPV vaccine initiation and completion. Missed opportunities were frequent and suggest additional barriers need to be addressed for insured populations. Evidence based strategies shown to improve coverage at the practice level include standing orders, reminder recall, and AFIX (Assessments of vaccine uptake, Feedback on coverage to providers, Incentives and Exchange of information) [31]. Future evaluations of MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database on vaccine uptake using this female cohort will be useful to provide additional data on vaccine initiation and completion.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

The present study provides additional information on missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination in the clinical setting. Most unvaccinated females (96.1%) had at least one missed vaccination opportunity. Focusing vaccination efforts on these visits could greatly increase coverage.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no affiliations, financial agreements, or other involvement of any authors with any company whose product figures prominently in this article.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Disease Control. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine, recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunne EF, Markowitz LE, Chesson H, et al. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in Males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Disease Control. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 through 17 years—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Disease Control. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 Years—United states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:685–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Disease Control. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007–2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2013—United states. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:591–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:620–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laz TH, Rahman M, Berenson AB. An update on human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 11–17 year old girls in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vaccine. 2012;30:3534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anhang Price R, Tiro JA, Saraiya M, et al. Use of human papillomavirus vaccines among young adult women in the United States: An analysis of the 2008 national health interview survey. Cancer. 2011;117:5560–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MarketScan database. Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Technical specifications for physician measurement. DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2009. HEDIS: Healthcare effectiveness data and information set. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elam-Evans L, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:625–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for human papillomavirus vaccination of adolescent girls and young women in a managed care organization. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:357–67. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook RL, Zhang J, Mullins J, et al. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in Medicaid. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:596–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong CA, Taylor JA, Wright JA, et al. Missed opportunities for adolescent vaccination, 2006–2011. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokley S, Cohn A, Dorell C, et al. Adolescent vaccination coverage levels in the United States: 2006–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1078–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dempsey AF, Cowan AE, Broder KR, et al. Adolescent Tdap vaccine use among primary care physicians. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oster NV, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Averhoff F, Howell K. Barriers to adolescent immunization: A survey of family physicians and pediatricians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:13–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: A survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126:425–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn JA, Cooper HP, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations and agreement with mandated human papillomavirus vaccination for 11-to-12-year-old girls: A statewide survey of Texas physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2325–32. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss TW, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination of males: Attitudes and perceptions of physicians who vaccinate females. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes CC, Jones AL, Feemster KA, Fiks AG. HPV vaccine decision making in pediatric primary care: A semi-structured interview study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young JL, Bernheim RG, Korte JE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination recommendation may be linked to reimbursement: A survey of Virginia family practitioners and gynecologists. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goff SL, Mazor KM, Gagne SJ, et al. Vaccine counseling: A content analysis of patient-physician discussions regarding human papilloma virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29:7343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, et al. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30:3546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008–2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:830–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pourat N, Jones JM. Role of insurance, income, and affordability in human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:320–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dempsey A, Cohn L, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Worsening disparities in HPV vaccine utilization among 19–26 year old women. Vaccine. 2011;29:528–634. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor LD, Hariri S, Sternberg M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2008. Prev Med. 2011;52:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.HHS. [Accessed December 1, 2014];About the Law. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/index.html.

- 31. [accessed 08/27/2013]; [Accessed December 1, 2014];The Community Guide. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/index.html.