Abstract

Objective

To investigate the clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACL reconstruction (ACLR) with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation.

Design

Systematic review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines.

Data sources

Embase, MEDLINE Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL and Google scholar from 1 January 1974 to 31 January 2017.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Study designs reporting outcomes in adults after arthroscopic, primary ACLR with hamstring autograft and accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation.

Results

Twenty-four studies were included in the review. The clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated brace-free rehabilitation were the following: (1) early start of open kinetic exercises at 4 weeks in a limited range of motion (ROM, 90°−45°) and progressive concentric and eccentric exercises from 12 weeks did not alter outcomes, (2) gender and age did not influence clinical outcomes, (3) anatomical reconstructions showed better results than non-anatomical reconstructions, (4) there was no difference between single-bundle and double-bundle reconstructions, (5) femoral and tibial tunnel widening occurred, (6) hamstring tendons regenerated after harvest and (7) biological knowledge did not support return to sports at 4–6 months.

Conclusions

After hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated brace-free rehabilitation, clinical outcome is similar after single-bundle and double-bundle ACLR. Early start of open kinetic exercises at 4 weeks in a limited ROM (90°−45°) and progressive concentric and eccentric exercises from 12 weeks postsurgery do not alter clinical outcome. Further research should focus on achievement of best balance between graft loading and graft healing in the various rehabilitation phases after ACLR as well as on validated, criterion-based assessments for safe return to sports.

Level of evidence

Level 2b; therapeutic outcome studies.

Keywords: hamstring autograft, ACL reconstruction, accelerated rehabilitation, clinical outcomes, graft remodelling

What is already known?

Accelerated rehabilitation, defined as early-unrestricted motion, immediate weight-bearing and eliminating the use of immobilising braces, is appropriate after ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon grafts.

Advantages of accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation protocols after ACL reconstruction are earlier normal function of the knee and immediate weight-bearing postsurgery.

Hamstring tendon ACL autografts undergo an intra-articular remodelling process.

What are the new findings?

After hamstring tendon autograft ACL reconstruction with accelerated brace-free rehabilitation:

Strong evidence suggests that clinical outcome is similar after single-bundle and double-bundle ACL reconstruction.

Moderate evidence suggests that early start of open kinetic exercises at 4 weeks in a limited range of motion (90°−45°) and progressive concentric and eccentric exercises from 12 weeks postsurgery do not alter clinical outcome.

Introduction

Rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction (ACLR) could be described as adaptations to a complex biological system.1 Outcomes after ACLR are influenced by both surgical and rehabilitation factors. ACL surgery requires the understanding of several factors: anatomical graft placement, mechanical properties of the selected graft tissue, mechanical behaviour and fixation strength of fixation materials as well as the biological processes that occur during graft remodelling, maturation and incorporation.1–5 These factors influence directly the mechanical properties of the knee joint after ACLR and should, in combination with rehabilitation progress, dictate the time course until normal function of the knee joint can be expected.5 6

After surgery, graft healing is characterised by a remodelling process.2 3 5 8 9 During this period, the graft will undergo changes, becoming morphologically similar to intact ligament tissue.2 5 9–11 Contemporary rehabilitation—defined as early-unrestricted motion, immediate weight-bearing and eliminating the use of immobilising braces—is appropriate after ACLR with patellar tendon grafts.12–20 However, conclusions are unclear when evaluating the effects of this type of rehabilitation after hamstring autograft ACLR.1 This is important because the hamstring tendons are a popular graft source for ACLR.7 Advantages of accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation protocols after ACLR are earlier normal function of the knee, weight-bearing and alleged ability to return to even most strenuous activities after primary ACLR at 6 months.2 5 10 15 21–26 A major challenge in postoperative rehabilitation after ACLR is optimising the balance between muscular strengthening exercises and loading of the graft to stimulate graft cells to produce cellular and extracellular components for the preservation of graft stability, without compromising graft integrity, which might result into an early elongation of the ACLR.2 5 11 15 27 28

The purpose of this systematic review is to present the current knowledge on outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation in adults. The primary aim was to examine the influence of different rehabilitation protocols, patient characteristics and surgical techniques on clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR. The secondary aim was to examine the influence of contemporary rehabilitation on tunnel widening, tendon regeneration and time to return to sports after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR.

Methods

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).29 We had six key review questions:

How do differences in rehabilitation protocols affect clinical outcomes?

How do different patient characteristics affect clinical outcomes?

How do different non-anatomical and anatomical surgical techniques affect clinical outcomes?

Does accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation influence tunnel widening?

Do hamstring tendons regenerate after harvest?

Does the current biological knowledge on hamstring tendon autografts support early return to sports?

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the systematic review are presented in box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Studies (meta-analysis, randomised, non-randomised, systematic reviews, case series, prospective or retrospective design) evaluating outcome in adult patients undergoing isolated ACL reconstruction (ACLR).

Studies must have included an accelerated rehabilitation protocol. Accelerated rehabilitation is characterised by immediate postoperative weight-bearing, without restriction in motion and brace-free rehabilitation. Return to sports is allowed after 4–6 months.

Any arthroscopic surgical method of primary intra-articular ACLR.

Hamstring tendon autograft.

Human in vivo studies with reported outcome.

English language.

Abstract and full text available.

Exclusion criteria

Concomitant surgery limiting an accelerated rehabilitation protocol (meniscal repair or transplant, osteotomy, microfracture, autologous cartilage implantation or matrix autologous chondrocyte implantation).

Revision surgery.

Allografts, bone–patellar tendon graft, quadriceps tendon or synthetic grafts.

Multiligament reconstructions.

Posterolateral, medial or posterior cruciate ligament instability.

Non-defined rehabilitation protocol.

Children and adolescents.

Animal or cadaveric (in vitro) studies.

Non-arthroscopic ACLR.

Non-English language.

Abstract or full text not available.

Electronic search

A systematic electronic search was performed using specific search terms in the following databases: Embase, MEDLINE Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL and Google scholar from 1 January 1974 to 31 January 2017 (online supplementary file 1).

bmjsem-2017-000301supp001.tiff (321.4KB, tiff)

Study selection

All potentially eligible articles were screened by title, abstract and full text by two teams of reviewers (RPAJ and NvM, and RPAJ and JBAvM). When two reviewers did not reach consensus, a third reviewer (NvM or JBAvM) made the final decision. We screened the reference lists of excluded and included articles for potentially eligible articles that may have been missed in the electronic database search.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (RPAJ and NvM), and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

We extracted data on key variables regarding surgical techniques, graft type, patient demographics, details of rehabilitation, patient-reported outcome, clinical outcome measures and radiological evaluation.

Synthesis of results

Due to substantial heterogeneity with regard to surgical techniques, populations, outcome and study design, it was not possible to pool data for statistical analysis. Instead, we used a best-evidence synthesis30 31 with the following ranking of levels of evidence:

Strong evidence is provided by two or more studies with good quality (low risk of bias) and by generally consistent findings in all studies (≥75% of the studies reported consistent findings).

Moderate evidence is provided by one good quality (low-risk of bias) study and two or more questionable quality (higher risk of bias) studies and by generally consistent findings in all studies (≥75%).

Limited evidence is provided by one or more questionable quality (higher risk of bias) studies or one good quality (low-risk of bias) study and by generally consistent findings (≥75%).

Conflicting evidence is provided by conflicting findings (<75% of the studies reported consistent findings).31

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (RPAJ and NvM) assessed the risk of bias of the articles independently. If the two reviewers did not reach consensus, a third reviewer (JBAvM) made the final decision. The reviewers were not blinded for author, journal or publication. The assessment of risk of bias of all articles was performed by standardised checklists of the Dutch Cochrane Library (www.netherlands.cochrane.org/beoordelingsformulieren-en-andere-downloads), namely for therapy and prevention (intervention, randomised controlled trials (RCTs)) and for prognosis (cohort studies).

The assessment of risk of bias for RCTs used nine criteria, displayed in table 1. These nine items could be rated ‘yes’ (+), ‘no’ (−) or ‘do not know’ (?). The same list was used for assessing clinical controlled trials, but these scored a ‘no’ for items 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Cochrane criteria for the assessment of RCTs and cohort studies

RCT |

Cohort studies |

|---|---|

1. Is a method of randomisation applied? |

1. Are study groups clearly defined? |

2. Is randomisation blinded? |

2. Is there any selection bias? |

3. Are the patients blinded? |

3. Is the exposure clearly defined? |

4. Is the therapist blinded? |

4. Is the outcome clearly defined? |

5. Is the outcome assessor blinded? |

5. Is the outcome assessment blinded? |

6. Are the groups comparable? |

6. Is the follow-up accurate? |

7. Is there an acceptable lost-to-follow-up? |

7. Is there an acceptable lost-to-follow-up? |

8. Is there an intention-to-treat? |

8. Are confounders described and/or eliminated? |

9. Are treatments comparable? |

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

The assessment of risk of bias for cohort studies described eight items, displayed in table 1. All eight items could be rated positive (+), negative (−) or ‘do not know’ (?). The same list was used for cross-sectional studies, but these scored a ‘−’ for item 2 because the study design could cause a selection bias.

We also evaluated two additional items due to their influence on outcome after ACLR and contemporary rehabilitation: (1) accurate description of the rehabilitation protocol and (2) ratio of men and women participating in the study. A final judgement of ‘good’, ‘questionable’ or ‘poor’ was given to every article. A ‘good’ was assigned to articles scoring positive for more than 50% of all items (low risk of bias); a ‘questionable’ if the positive score was between 30% and 50% (questionable risk of bias) and a ‘poor’ was assigned to articles with a positive score inferior to 30% (high risk of bias). The articles with a total score of ‘good’ and ‘questionable’ were included in the review.

Results

Study selection

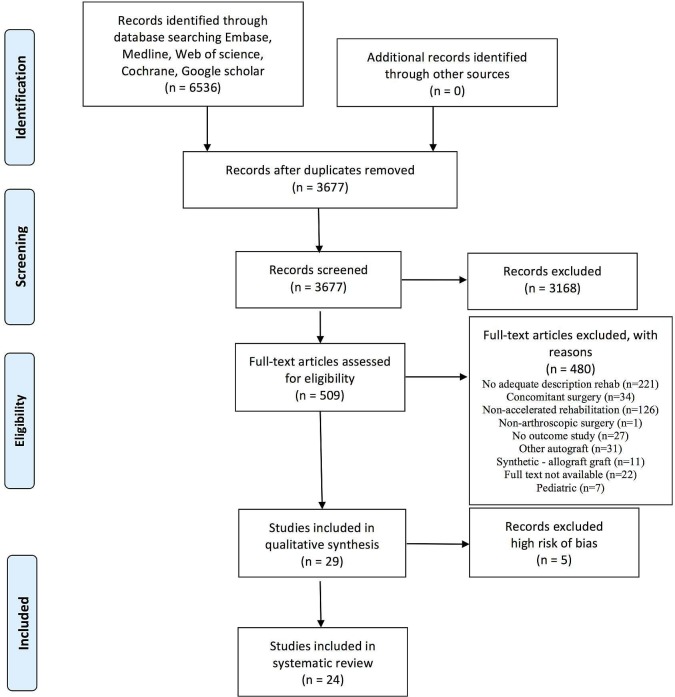

The PRISMA flow chart of the systematic review is presented in figure 1. A total of 29 studies were selected for the risk of bias assessment: 6 RCTs,10 12 32–354 clinical controlled trials,36–39 12 prospective cohort studies,21 40–504 cross-sectional studies,9 51–53 and 3 retrospective cohort studies.54–56

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis flow diagram. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Risk of bias assessment

The results of the risk of bias assessment for the included studies are presented in tables 2 and 3. Five articles were discarded because of the total score ‘poor’ after quality appraisal. Twenty-four articles were included in the systematic review.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of RCTs and CCTs

Article |

Study design |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

Accurate description rehabilitation |

Men–women ratio |

Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baltaci et al32 |

RCT |

+ |

+ |

− |

? |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Good |

Christensen et al12 |

RCT |

+ |

+ |

? |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Good |

Fukuda et al10 |

RCT |

+ |

+ |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

Good |

Kinikli et al33 |

RCT |

+ |

? |

+ |

− |

− |

+ |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

Questionable |

Koutras et al36 |

CCT |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

Good |

Melikoglu et al37 |

CCT |

− |

− |

? |

? |

? |

+ |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

Poor |

Salmon et al38 |

CCT |

− |

− |

? |

? |

? |

? |

− |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Questionable |

Sastre et al34 |

RCT |

+ |

+ |

? |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Good |

Treacy et al39 |

CCT |

− |

− |

? |

? |

? |

+ |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

Poor |

Vadalà et al35 |

RCT |

+ |

+ |

? |

? |

? |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

Good |

CCT, clinical controlled trial; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment of cohort and cross-sectional studies

Article |

Study design |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Accurate description rehab. |

Men–women ratio |

Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Åhlén et al54 |

RC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

Good |

Ali et al51 |

CS |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

? |

− |

? |

+ |

− |

Questionable |

Biernat et al40 |

PC |

− |

− |

− |

− |

? |

? |

? |

− |

+ |

+ |

Poor |

Boszotta et al41 |

PC |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

? |

? |

− |

− |

? |

Poor |

Clark et al52 |

CS |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

? |

? |

− |

+ |

Questionable |

Czamara et al42 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

Good |

Czaplicki et al46 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

? |

− |

− |

− |

Questionable |

Hill et al43 |

PC |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

− |

? |

− |

− |

Poor |

Howell et al21 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

− |

Good |

Janssen et al9 |

CS |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

? |

Good |

Janssen et al ref44 |

PC |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

Good |

Jenny et al47 |

PC |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

− |

+ |

Good |

Karikis et al48 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

− |

+ |

Good |

Koutras et al49 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

− |

− |

Questionable |

Królikowska et al53 |

CS |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

− |

+ |

− |

+ |

− |

Questionable |

Srinivas et al50 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

− |

− |

Questionable |

Toanen et al56 |

RC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

− |

− |

+ |

Questionable |

Trojani et al55 |

RC |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

+ |

? |

+ |

− |

Good |

Zaffagnini et al45 |

PC |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

Good |

CS, cross-sectional study; PC, prospective cohort study; RC, retrospective cohort study; rehab., rehabilitation.

Details of studies and rehabilitation

The details of the included studies are presented in table 4. The details of accelerated rehabilitation of the 24 included studies are presented in table 5.

Table 4.

Details of the included studies

Rehabilitation |

N |

Gender (M to F) |

Participant groups |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Åhlén et al54 |

19 |

10 to 9 |

Operated versus contralateral leg |

8.5 (6–11) years |

Significant increase in Tegner, Lysholm and hop test postoperative versus preoperative ST and G regenerated in, respectively, 89% and 95% of patients with almost normal insertion pes anserinus. Regenerated tendons had similar cross-sectional area compared with contralateral leg. Strength deficit in deep flexion but not in internal rotation. |

Ali et al51 |

78 |

69 to 5 |

NA |

64 (48–84) months |

Detachment of tibia insertion is unnecessary and an accelerated rehab. can be followed without brace use. |

Baltaci et al32 |

30 |

All males |

Wii Fit (15) versus conv rehab. (15) |

12 weeks |

Both rehab. programme have same effect on muscle strength, dynamic balance and functional performance. Practice of Wii Fit activities could address physical therapy goals. |

Christensen et al12 |

36 |

53% male (aggressive rehab.) versus 88% male non-aggressive rehab. |

Aggressive (19) versus non-aggressive rehab. (!17) |

24 weeks |

No difference between aggressive and non-aggressive rehabilitation in AP laxity, subjective IKDC scores, ROM and muscle strength. |

Clark et al52 |

82 |

27 to 14 in each group |

41 ACLR versus 41 controls |

12 months |

Significant increases in asymmetry in ACLR group for all outcome measures except symmetry index relative to operated limb. Weight-bearing asymmetry can be assessed with Wii Fit balance board. |

Czamara et al42 |

30 |

All males |

SB ACLR (15) versus DB ACLR (15) |

24 weeks |

No differences between SB versus DB ACLR in AP laxity, pivot shift test, ROM, joint circumference, pain scores, peak torque muscles tibial rotation and run test. |

Czaplicki et al46 |

29 |

All males |

NA |

12 months |

1 year after ACLR may be too early to return to full physical fitness for males who are physically active. |

Fukuda et al10 |

49 |

Early start 16 to 7) versus late start (13 to 9) |

Early start (25) versus late start (24) |

17 (13–24) months |

Faster recovery quadriceps strength in early group. No difference between early and late start of open kinetic chain exercises in pain and functional improvement. |

Howell et al21 |

41 |

28 to 13 |

NA |

26 (24–32) months |

Absent pivot shift in 82% patients and 88% <3 mm laxity difference with KT-1000. Stability, girth of thigh, Lysholm and Gillquist scores were identical at 4 months and 2 years. |

Janssen et al9 |

67 |

6–12 ms (9 to 6), 1–2 years (10 to 6), >2 years post-ACLR (7 to 10) |

Group 1 (15), group 2 (16), group 3 (11) |

117 months |

Human hamstring autografts remain viable after ACLR and showed three typical stages of graft remodelling. Remodelling in humans takes longer compared with animal studies and is not complete up to 2 years after ACLR. |

Janssen et a ref 44 |

22 |

17 to 5 |

MRI operated and contralateral leg |

12 months |

Gracilis regenerated in all patients, ST in 14/21 patients. There was no relation between isokinetic flexion strength and tendon regeneration. |

Jenny et al47 |

72 |

57 to 15 |

NA |

4.3 years |

Patient-based decision to return to work and sport was possible without compromising functional outcome. The postoperative restrictions implemented by orthopaedic surgeons following ACLRs may be relaxed and more patient based. |

Karikis et al48 |

94 |

DB (32 to 13) versus SB (31 to 18) |

DB (45) versus SB (49) ACLR |

26 (22–34) months |

Anatomical DB ACLR did not result in better rotational or AP stability compared with anatomical SB ACLR. |

Kinikli et al33 |

33 |

33 to 2 |

Study group (16) versus control (17) |

16 weeks |

Adding progressive eccentric and concentric exercises may improve the functional results after ACLR with autograft hamstring tendons. |

Królikowska et al53 |

40 |

All males |

ST group (20) versus ST-G group (20) |

6 months |

Generally, no difference between ST and ST-G groups. There is an influence of gracilis tendon harvest on internal shin rotation isometric torque at deep internal rotation angle. |

Koutras et al36 49 |

42 |

39 to 3 |

NA |

9 months |

Measuring knee flexion strength in prone demonstrates higher deficits than in conventional seated position. |

Salmon et al38 |

200 |

100 to 100 |

Men versus women |

7 years |

Significant greater laxity in women compared with men without effect on activity level, graft failure, subjective and functional assessments. |

Sastre et al34 |

40 |

DB (70% male) versus SB (70% male) ACLR |

DB (20) versus SB (20) ACLR |

2 years |

No significant differences in DB versus SB ACLR in IKDC objective and subjective results. |

Srinivas et al50 |

63 |

58 to 5 |

Various fiaxtion systems femur and tibia |

1 year |

Femoral and tibial tunnel widening varies with different methods and was maximum with suture disc method compared with others after ACLR with hamstring autograft. |

Toanen et al56 |

12 |

5 to 7 |

NA |

49.6 (24) months |

Older patients (>60 years) and active patients with non-arthritic ACL-deficient knees showed good results on functional recovery without risk of midterm OA. |

Trojani et al55 |

18 |

6 to 12 |

NA |

30 (12–59) months |

Age >50 years is not a contraindication to select hamstring tendon autograft for ACLR. ACLR restores knee stability but does not modify pain in case of previous medial meniscectomy. |

Vadalà et al35 |

45 |

33 to 12 |

Acc rehab (20) versus conv rehab. (25) |

10 (9–11) months |

Bone tunnel enlargement can be increased by accelerated rehab. after ACLR with hamstring tendon autografts. |

Zaffagnini et al45 |

21 |

All males |

NA |

48.1 (46–50) |

Return to sports was 95% after 1 year and 64% after 4 years in professional soccer players after non-anatomical quadruple hamstring tendon autograft ACLR. 71% still played competitive soccer at final follow-up. Clinical scores were restored after 6 months. |

ACLR, ACL reconstruction; AP, anterioposterior; conv, conventional; DB, double bundle; F, female; G, gracilis tendon; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; M, male; NA, not applicable; OA, osteoarthritis; rehab., rehabilitation; ROM, range of motion; SB, single-bundle; ST, semitendinosus tendon; ST-G, semitendinosus/gracilis.

Table 5.

Details rehabilitation

Rehabilitation |

Preoperative rehabilitation |

ACL graft |

Brace |

Full weight-bearing allowed |

FROM allowed |

CKC exercises |

OKC exercises |

Concentric exercises |

Eccentric exercises |

Running |

Return to light sports |

Unrestricted return to sports |

Criteria for return to sports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Åhlén et al54 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

6 weeks |

? |

? |

3 months |

? |

6 months |

Subjective functional stability compared with contralateral leg |

Ali et al51 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate (Programme Shelbourne) |

Immediate |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

? |

6 months |

9 months |

Stable knee (Lachman and pivot test) and asymptomatic knee |

Baltaci et al32 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

6–8 weeks |

3–4 weeks |

6–8 weeks? |

3 months |

6–8 months |

6–8 months |

? |

Christensen et al12 |

? |

HS |

Brace versus no brace |

Immediate (Programme Biggs) |

Immediate |

Programme Biggs |

Programme Biggs |

? |

? |

8–12 weeks |

? |

? |

? |

Clark et al52 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

? |

3–4 months |

? |

? |

? |

Czamara et al42 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

6–12 weeks? |

6 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

4 months |

? |

? |

? |

Czaplicki et al46 |

Yes |

HS |

No |

Immediate (Programme Shelbourne) |

Immediate |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

? |

? |

? |

? |

Fukuda et al10 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

2 weeks |

4 vs 12 weeks |

? |

? |

10 weeks |

? |

? |

? |

Howell et al21 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

4 weeks |

4 weeks |

? |

? |

8–10 weeks |

? |

4 months |

? |

Janssen et al9 ref 9 and 44 |

Yes |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

6 weeks |

6 weeks (start 90°−40°) 10 weeks (FROM) |

6 weeks (start 90°−40°) 10 weeks (FROM) |

10 weeks |

4 months |

4–6 months |

? |

Jenny et al47 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

? |

4 months |

4 months |

4–6 months |

Patient-based decision |

Karikis et al48 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate (‘accelerated’ programme) |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

3 months |

? |

6 months |

Full functional stability in muscle strength, coordination, balance compared with uninvolved leg |

Kinikli et al33 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate (Programme Wilk/Majima) |

Immediate |

Immediate |

6–8 weeks |

3 weeks (study group) |

3 weeks (study group) |

? |

? |

? |

? |

Królikowska et al53 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

1–5 weeks |

? |

6–12 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

13–20 weeks |

21 weeks |

6 months |

? |

Koutras et al36 49 |

Yes |

HS |

No |

Immediate (Programme Shelbourne) |

immediate |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

Programme Shelbourne |

? |

? |

? |

? |

Salmon et al38 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

6 weeks |

? |

6 months |

Rehabilitation goals met |

Sastre et al34 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

? |

12 weeks |

? |

6–9 months |

? |

Srinivas et al50 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Second day |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

6 months |

? |

Toanen et al56 |

? |

HS |

No |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

? |

6–12 weeks |

3–6 months |

6 months |

? |

Trojani et al55 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

8 weeks |

? |

6 months |

? |

Vadalà et al35 |

? |

HS |

Brace versus no brace |

Immediate |

Immediate versus 2 weeks |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

3 months |

? |

? |

? |

Zaffagnini et al45 |

? |

HS |

No |

Immediate |

Immediate |

Immediate |

? |

? |

? |

2 months |

? |

4 months |

Criteria for on field rehabilitation, not for return to unrestricted sports |

CKC, closed kinetic chain; FROM, full range of motion; HS, hamstring autograft; OKC, open kinetic chain.

Results of individual studies and answers to research questions

How do differences in rehabilitation protocols affect clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation?

Czaplicki et al46 prospectively evaluated serial changes in isokinetic muscle strength preoperatively and postoperatively. They found significant differences between extension peak torques for the injured and healthy limbs at all stages of accelerated rehabilitation. At 1 year, there was still a deficit in muscle strength of the operated leg.46

The effects of accelerated brace-free free rehabilitation versus rehabilitation with brace and limited ROM for 4 weeks postsurgery were examined by Christensen et al.12 No differences were found between the two groups for IKDC, range of motion (ROM) and peak isometric force at 12 weeks postsurgery.12

Fukuda et al10 evaluated the outcome of early start of open kinetic chain exercises in a restricted ROM at 1 year after non-anatomical, four-strand hamstring ACLR. A start of open kinetic chain quadriceps exercises at 4 weeks postoperatively in a restricted ROM (90°−45°) did not differ from a start at 12 weeks in terms of anterior knee laxity, pain and functional improvement. The early start group showed a faster recovery for quadriceps strength (19 weeks vs 17 months).10

The effect of progressive eccentric and concentric training at 12 weeks on functional performance after four-strand hamstring ACLR was investigated by Kinikli et al.33 Outcome measures were isokinetic muscle strength, single and vertical hop tests, Lysholm score and ACL Quality of Life Questionnaire. There was a significant improvement of all outcome measures except for isokinetic strength of knee extensors and flexors.33

Baltaci et al32 compared a 12-week Nintendo Wii Fit versus a conventional accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation after hamstring ACLR. The two different 12-week physiotherapy programme had the same effect on muscle strength, dynamic balance and functional performance values.32 Clark et al52 used the Nintendo Wii Fit Balance Board to assess weight-bearing asymmetry during squatting as outcome after hamstring autograft ACLR with accelerated rehabilitation. The authors found significant increases in asymmetry after ACLR compared with a matched control group.52

Jenny et al47 assessed functional outcome (sport activity, Tegner, Lysholm and IKDC subjective score) and rerupture rate after patient-based decision to return to work and sports. Return to work was possible for 96% of patients after a mean delay of 2.3 months. Return to sports was 92%, 6.1 months for pivoting sports and 6.6 months for contact sports. A 6% rerupture rate occurred after a new significant knee injury.47 Assessing time to return to sports based on muscle strength may also be influenced by testing technique. Koutras et al49 compared knee flexion isokinetic strength deficits between seated and prone positions after hamstring autograft ACLR with accelerated rehabilitation. Peak torque knee flexion deficits were higher in the prone position compared with the conventional seated position by an average of 6.5% at 60°/s and 9.1% at 180°/s (p<0.001). At 9 months after hamstring ACLR, most athletes would not be cleared to return to sports if tested in prone position.49

Brace-free accelerated rehabilitation after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR, early start of open kinetic chain quadriceps exercises at 4 weeks in a limited knee ROM (90°−45°) and progressive concentric and eccentric exercises from 12 weeks do not alter clinical outcomes (‘moderate’ level of evidence).

Isokinetic extension peak torque deficit is still present at 1 year after accelerated rehabilitation. The use of Nintendo Wii Fit activities could address weight-bearing asymmetry and physical therapy goals (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Patient-based decision to return to work and sports is possible without compromising functional outcome (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Measuring knee flexion strength in prone position shows larger knee flexion isokinetic deficits compared with the conventional seated position (‘limited’ level of evidence).

How do different patient characteristics affect clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation?

Gender

Salmon et al38 did not find significant gender differences for graft rupture, activity level, self-reported or functional assessment or radiological outcome. Women did have significantly greater laxity than men on the Lachman test, pivot shift test and KT-1000 mean manual maximum testing at all time points. The higher laxity measurements did not influence the self-reported and functional outcome assessments.38

Gender does not influence clinical outcomes after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free, rehabilitation (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Age

Trojani et al55 retrospectively analysed the same ACLR technique as Salmon et al38 in patients >50 years. Surgery restored knee stability but did not modify pain in patients with previous medial meniscectomy. Graft failure did not occur. The authors concluded that age over 50 years is not a contraindication to select a hamstring autograft for ACLR.55 Toanen et al56 demonstrated that older and active patients >60 years without osteoarthritis showed good results after single-bundle hamstring autograft ACLR. The majority of patients (83%) returned to sports activities with 50% returning to their preinjury level of activity.56

Age >50 years does not influence clinical outcome after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation (‘limited’ level of evidence).

How do different non-anatomical and anatomical surgical techniques of hamstring tendon autograft ACLR affect clinical outcomes after accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation?

Non-anatomical single tunnel four-strand hamstring tendon autograft ACLR

Three studies have examined this surgical technique.21 45 51

Howell et al21 presented a single surgeon prospective cohort series of transtibial ACLR technique with special attention to intercondylar roof impingement. Patients returned to unrestricted sports and work activities after 4 months. The authors justified the early return to vigorous activities at 4 months by unchanged knee stability, girth of the thigh, knee extension as well as Lysholm and Gillquist scores at 2-year follow-up.21

Ali et al51 presented the outcomes of a single surgeon, cross-sectional study of transtibial non-anatomical ACLR using a hamstring graft without detachment of its tibial insertion. Follow-up was 64 (range 48–84) months. All patients achieved full ROM with a mean KT-1000 side-to-side difference of 1.43 (SD 3.86) and negative pivot shift test. The authors concluded that their technique showed satisfactory and comparable results to studies with conventional detachment of hamstring tendons from their tibial insertion.51

Zaffagnini et al45 analysed return to sports in a homogeneous group of male professional soccer players after ACLR. Follow-up was 4 years. The authors used a non-anatomical, four-strand hamstring technique with additional extra-articular fixation of the graft. After 12 months, 95% of patients returned to the preoperative professional soccer level. Mean time from surgery to first official match was 186 (range 107–282) days. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores reached the plateau level at 6 months postoperatively. At 4 years, 71% still played professional soccer, 62% at the same preoperative level and 9% in a lower division. Five per cent of patients experienced rerupture of the ACLR.45

Non-anatomical transtibial four-strand hamstring ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation is associated with good clinical results. Return to sports was possible at 4–6 months postsurgery (‘moderate’ level of evidence).

Non-anatomical versus anatomical hamstring tendon autograft ACLR

Koutras et al36 compared the short-term functional and clinical outcomes between a non-anatomical transtibial versus an anatomical anteromedial ACL technique. The anteromedial approach group had better Lysholm scores at 3 months and better performance in the timed lateral movement functional tests at 3 and 6 months. All other comparisons were non-significant.36

Anatomical ACLR shows better short-term results than non-anatomical ACLR after accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Single-bundle versus double-bundle hamstring tendon autograft ACLR

Sastre et al34 compared anatomical four-strand single-bundle and double-bundle hamstring ACLR in a randomised prospective study. The authors did not find any difference between the two groups with respect to anterior laxity, pivot shift test, IKDC subjective and objective scores.34 In a similar study, Czamara et al42 found no differences between the two groups for anterior tibial translation, pivot shift test, ROM and joint circumference, subjective assessment of pain and knee joint stability, peak torque for internal and external rotation and run test with maximal speed and change of direction manoeuvres.42 Karikis et al found that anatomical double-bundle ACLR did not result in better rotational or anteroposterior stability measurements than anteromedial portal non-anatomical single-bundle reconstruction at 2-year follow-up.48

There is no difference in clinical results between single-bundle and double-bundle hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation (‘strong’ level of evidence).

Semitendinosus versus combined semitendinosus/gracilis autograft ACLR

Krolikowska et al53 assessed isometric and peak torque of muscles responsible for internal and external rotation of the lower leg post-ACLR after a 6-month accelerated brace-free rehabilitation programme. There was no difference between patients reconstructed with only the semitendinosus autograft (ST) compared with patients reconstructed with a combined semitendinosus/gracilis autograft (STGR). There was, however, a significant difference in isometric internal rotation strength in the operated knee compared with the uninvolved knee at 25° of internal rotation in the STGR group.53

There is an influence of additional gracilis harvest in internal rotation strength at a deep internal rotation angle (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Does accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR influence tunnel widening?

Vadalà et al35 analysed tunnel widening after four-strand hamstring tendon ACLR by means of CT scan comparing accelerated brace-free rehabilitation versus non-accelerated rehabilitation with brace. Mean follow-up was 10 months. There was a significant increase in femoral and tibial tunnel diameter after accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation.35 The extend of tunnel widening with hamstring autograft and accelerated brace-free rehabilitation was measured by Srinivas et al50 with CT at 1-year follow-up: femoral and tibial tunnel widening varied with different methods of fixation and was maximal in the tibia with suture disc method compared with interference screw fixation.50

Accelerated, brace-free, rehabilitation after hamstring tendon autograft ACLR causes increased tunnel widening on both the femur and tibia (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Do hamstring tendons regenerate after harvest for ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation?

Regeneration of hamstring tendons in the upper leg after harvest for ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation was examined in two studies.44 54 Ahlen et al54 performed a retrospective MRI study with 6-year follow-up after hamstring tendon harvest. The gracilis tendon regenerated in 18 of 19 patients, the ST tendon in 17 of 19 patients.54 Janssen et al44 performed a prospective MRI study in 22 patients with follow-up at 6 and 12 months. Regeneration of the gracilis tendon occurred in all patients, the ST tendon regenerated in 14 of 22 patients. The majority of tendons regenerated distal to the joint line of the knee. The authors did not find a significant relationship between isokinetic flexion strength and tendon regeneration.44

Hamstring tendons regenerate after harvest for ACLR. There is no evidence to support a relationship between increased isokinetic flexion strength and tendon regeneration (‘strong’ level of evidence).

Does the current biological knowledge of the hamstring graft support early return to sports after ACLR with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation?

Janssen et al9 examined 67 midsubstance biopsies after clinically successful four-strand hamstring autograft ACLR with a standardised accelerated rehabilitation programme. Cellular density and vascular density were increased up to 24 months after ACLR. Especially the strong increase in myofibroblast density, from 13 to 24 months, indicated an active remodelling process from 1 to 2 years. Furthermore, vessel density increased over 24 months, whereas cell and myofibroblast density decreased but stayed higher than native hamstring and ACL controls. Collagen orientation did not return to normal in the study period. The authors question whether early return to sports (4–6 months) after accelerated rehabilitation is to be recommended after hamstring ACLR.9

Intra-articular hamstring graft remodelling is still active at 2 years after ACLR with an accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation. Based on the current evidence, the early return to sports after 4–6 months may be questionable (‘limited’ level of evidence).

Discussion

A significant body of literature has shown that accelerated rehabilitation—defined as early-unrestricted motion, immediate weight-bearing and eliminating the use of immobilising braces—is appropriate after ACLR with patellar tendon grafts.12–20 However, conclusions are unclear when evaluating the effects of this type of rehabilitation after hamstring autograft ACLR. There are several factors that need to be considered. First, hamstring autografts require fixation of soft tissue (tendon) to bone.57 A period of 8–12 weeks is necessary for proper incorporation of hamstring grafts in the bone tunnels.58 Fixation of this soft tissue graft is considered the ‘weak link’ early on after ACLR.58 59 In a systematic review, Han et al concluded that both intratunnel and extratunnel fixation methods of hamstring ACL autografts displayed comparable outcomes based on objective IKDC, Lysholm and Tegner scores, anterior knee laxity and return to sports timing.59

Second, the intra-articular remodelling of the ACL hamstring autograft requires an optimal equilibrium between muscle strength training and graft loading to prevent stretch out of the ACL graft.2 11 15 27 60 Finally, early after ACLR, relative protection of the autograft donor site must be considered. Therefore, force generation from the hamstrings should be minimised when a hamstring autograft is employed.58 In summary, accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation needs to restore knee function and at the same time stimulate optimal graft healing.61

Accelerated rehabilitation

This review presented a ‘moderate’ level of evidence that accelerated rehabilitation after hamstring ACLR does not alter clinical outcome compared with non-accelerated rehabilitation with knee brace.12 The rationale of using a knee brace is to protect the healing graft during the early phases of rehabilitation.23 Various systematic reviews could not substantiate this hypothesis based on clinical results.23 24 28 62 Furthermore, full weight-bearing without crutches within 10 days (with a normal gait pattern) improves quadriceps function, prevents patellofemoral pain and does not affect knee stability.24 62

This review showed that start of open kinetic chain quadriceps exercises with 90°−45° ROM at 4 weeks postsurgery does not alter the clinical outcome after hamstring autograft ACLR (‘moderate’ level of evidence). The combination of closed and open kinetic chain exercises protects the healing graft as a result of better dynamic lower extremity stability and neuromuscular control.61 Beynnon et al63 found similar maximum ACL strain values produced by active flexion–extension (an open kinetic chain exercise) and squatting (a closed kinetic chain exercise). They also demonstrated that increasing resistance during the squat exercise did not produce a significant increase in native ACL strain values, unlike increased resistance during active flexion–extension exercise.63 Escamilla et al58 showed that non-weight-bearing exercises generally loaded the ACL graft more than weight-bearing exercises and that, for both exercises, the ACL was loaded to a greater extent between 10° and 50° compared with 50° and 100° of knee flexion.58 These biomechanical findings are in agreement with the good clinical results presented in this review with the early start of open kinetic exercises in a limited ROM.10 64 Majima et al26 demonstrated that accelerated rehabilitation with open kinetic exercises started at 7–10 days after hamstring ACLR could rapidly restore muscle strength without significantly compromising graft stability. However, the incidence of synovitis of the knee was significantly increased after accelerated rehabilitation.26 Van Grinsven et al concluded in their systematic review on evidence-based rehabilitation after ACLR that there is increasing consensus that open kinetic chain exercises did not increase graft laxity (in and exceeding the safe range with a focus on endurance). Additionally, these exercises had a favourable effect on quadriceps strength.24

This review also demonstrated that start of eccentric and concentric muscle training at 12 weeks after surgery did not influence clinical outcome after hamstring autograft ACLR (‘moderate’ level of evidence). Therapeutic exercises that emphasise eccentric gluteus maximus, quadriceps femoris and gastrocnemius–soleus activation can improve lower extremity muscular shock absorption, prevent knee reinjury, enhance athletic performance, help heal lower extremity musculotendinous injuries, increase bone mineral density and decrease fall risk.61 Further research is warranted to determine the best timing of introducing open kinetic exercises and safe amount of progressive resistance training after ACLR with hamstring autografts.24 65

A critical remark is necessary when accelerated rehabilitation is discussed. There is little consensus in the literature about what composes an accelerated rehabilitation programme because few papers have described their protocol adequately.24 In this review, almost all included studies on accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation agreed that immediate weight-bearing, full ROM and closed kinetic exercises were permitted after hamstring autograft ACLR. However, if even specified at all, the programme varied in their timing and details of open kinetic chain exercises, frequency of concentric and eccentric training and neuromuscular training (table 4). Few studies described full details of the accelerated rehabilitation after hamstring ACLR. The rehabilitation programme by Shelbourne and Nitz was most often cited. This programme emphasised specific presurgical rehabilitation goals.23 24 26 46 61–63 Remarkably, only five studies in this review provided specific details of this prehabilitation.9 36 44 46 49 Furthermore, although referring to the aforementioned rehabilitation protocols, the timing of return to activities such as running or unrestricted sports varied widely among studies, often without specific criteria (table 4). The lack of details of accelerated rehabilitation programme after hamstring autograft ACLR makes it difficult to evaluate the potential disadvantages of accelerated rehabilitation such as tunnel widening35 66 and increased synovitis.26 Postoperative rehabilitation is a major factor contributing to the success of ACLR and needs to be defined in detail for adequate research on clinical outcome and safe return to sports.

Return to sports

Return to sports is often used as short-term to midterm outcome measure for ACLR and rehabilitation.25 In their meta-analysis of 69 articles, Ardern et al67 have shown that after ACLR, the overall return to some kind of sports activity is 81%.67 Sixty-five per cent of patients returned to their preinjury level and 55% to competitive sports at final follow-up.67 Younger age, male gender and a positive psychological response all favoured returning to the preinjury level sport.67 Elite athletes had more than twice the odds of returning to competitive sports compared with non-elite athletes.67 This is supported by the evidence in the present review with 95% return to sports 1 year after with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation.45 Elite male UEFA soccer league players needed 7 months to return to the first training after ACLR, 10 months to return to regular practice and 12 months to return to match play.68 69Grindem et al have shown that the return to play after 9 months postsurgery substantially reduces ACL graft rerupture rate.70 Leading ACL experts generally let their patients return to sports at 6 months in average and involvement in active competition at 8 months postsurgery.71 However, a recent study by Herbst et al showed that most patients, in terms of neuromuscular abilities and compared with healthy controls, were most likely not ready for a safe return to sports, even 8 months postoperatively. The most limiting factor was a poor Limb symmetry index (LSI) value of <90% if the dominant leg was involved and <80% if the non-dominant leg was involved.72 Gokeler et al found that the majority of patients who are 6 months after ACLR require additional rehabilitation to pass return to sports criteria.73 Further studies identifying sport-specific differences in ACR outcomes in athletes could further enhance accelerated rehabilitation programme for athletes after ACLR.45 73

Graft failure after ACLR is not uncommon even with improved ACLR techniques.2 3 Evidence-based evaluations did not prove a 4–6 months return to sports to be safe due to the fact that biological healing is not complete.2 9 69 74–76 This is also demonstrated in the current review: intra-articular hamstring graft remodelling was still active at 2 years after ACLR with an accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation.9 This may provide biological support for the findings by Paterno et al that in the 24 months after ACLR and return to sports, patients are at greater risk to suffer a subsequent ACL injury compared with young athletes without a history of ACL injuries.77 Considering the fact that rehabilitation protocols were extrapolated from animal in vivo studies, studies on human in vivo graft healing suggest a need for new postoperative rehabilitation schedules after ACLR with hamstring autografts.2 No final conclusions can be drawn on the mechanical strength of the healing ACL grafts in humans without any available technique for in vivo measurements of their mechanical properties.2 74

In this systematic review, only 20% of studies reported assessment criteria for return to sports after hamstring autograft ACLR. These criteria, however, lacked specific details for use in clinical practice or comparative scientific research. This is in agreement with previous reviews on return to sports after ACLR.28 78 79 Furthermore, commonly used muscle functional tests are not demanding or sensitive enough to identify differences between injured and non-injured sides.69 80 Large meta-analysis have shown that despite 90% of patients having normal validated outcome scores, only 44% of patients returned to competitive sports.79 81 Currently, there are no concrete guidelines that allow for a safe return to unrestricted activity.79 82 Further research is necessary to develop a validated set of criteria to determine safe return to sport-specific training and unrestricted activity.61 67 69 78 83

One of the strengths of this systematic review is that it presents all available knowledge on outcomes after hamstring tenson autograft ACLR with accelerated rehabilitation. This extensive search strategy was performed in several databases, for all relevant papers to be included. Furthermore, the PRISMA standard was applied to study selection, data collection, risk of bias assessment and reporting of results. This led to an extensive and complete overview of the current evidence on this topic with defined levels of evidence. As such, it is a useful paper for ACL experts in various fields of healthcare (eg, orthopaedic surgeons, physical therapists) and may facilitate interprofessional patient care. This systematic review also has limitations. Studies of different evidence levels were included in the search for all available knowledge on clinical outcome after accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation after ACLR. It must be noticed that the type of rehabilitation was not a primary intervention in all of the included studies. Some conclusions of the ‘best-evidence synthesis’ may therefore not be primarily related to accelerated rehabilitation. Another limitation is the inclusion of studies with limited number of patients. Furthermore, the ‘best-evidence synthesis’ by van Tulder et al31 for this review may have limited the level of evidence due to the quality and limited number of studies for specific research questions. Although strict and adapted for various study types, the risk of bias assessment of the Cochrane Library may limit the strength of evidence. It may be argued that a ‘low’ risk of bias RCT study is of higher level of evidence than a ‘low’ risk of bias prospective cohort study.

The inclusion of merely publications in English is another limitation.

Conclusions

After hamstring tendon autograft ACLR with accelerated brace-free rehabilitation, clinical outcome is similar after single-bundle and double-bundle ACLR. Early start of open kinetic exercises at 4 weeks in a limited ROM (90°−45°) and progressive concentric and eccentric exercises from 12 weeks postsurgery do not alter clinical outcome. Further research should focus on achievement of best balance between graft loading and graft healing in the various rehabilitation phases after ACLR as well as on validated, criterion-based assessments for safe return to sports.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Parts of the abstract of this paper have been presented at the 17th ESSKA Congress (4–7 May 2016) in Barcelona, Spain, as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in ‘Poster Abstracts’ in Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy.

Patient consent: Not required.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the search, screening, data collection, bias assessment and final writing of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement: We are willing to share any further details of this PRISMA systematic review.

References

- 1.Janssen RP. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction & accelerated rehabilitation. Hamstring tendons, remodelling and osteoarthritis [PhD thesis]. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Maastricht University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janssen RP, Scheffler SU. Intra-articular remodelling of hamstring tendon grafts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:2102–8. 10.1007/s00167-013-2634-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ménétrey J, Duthon VB, Laumonier T, et al. “Biological failure” of the anterior cruciate ligament graft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:224–31. 10.1007/s00167-007-0474-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Eck CF, Schreiber VM, Mejia HA, et al. “Anatomic” anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of surgical techniques and reporting of surgical data. Arthroscopy 2010;26(9 Suppl):S2–12. 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen RP, van Melick N, van Mourik JB. Similar clinical outcome between patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autograft after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with accelerated, brace-free rehabilitation: a systematic review. JISAKOS 2017. 10.1136/jisakos-2016-000110. [Epub ahead of print 15 Sep 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Seon JK, Jo AR. Current trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Relat Res 2013;25:165–73. 10.5792/ksrr.2013.25.4.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuelsson K, Andersson D, Ahldén M, et al. Trends in surgeon preferences on anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive techniques. Clin Sports Med 2013;32:111–26. 10.1016/j.csm.2012.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marumo K, Saito M, Yamagishi T, et al. The “ligamentization” process in human anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar and hamstring tendons: a biochemical study. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:1166–73. 10.1177/0363546504271973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen RP, van der Wijk J, Fiedler A, et al. Remodelling of human hamstring autografts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:1299–306. 10.1007/s00167-011-1419-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda TY, Fingerhut D, Moreira VC, et al. Open kinetic chain exercises in a restricted range of motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:788–94. 10.1177/0363546513476482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheffler SU, Unterhauser FN, Weiler A. Graft remodeling and ligamentization after cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:834–42. 10.1007/s00167-008-0560-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen JC, Goldfine LR, West HS. The effects of early aggressive rehabilitation on outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autologous hamstring tendon: a randomized clinical trial. J Sport Rehabil 2013;22:191–201. 10.1123/jsr.22.3.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Carlo M, Klootwyk TE, Shelbourne KD. ACL surgery and accelerated rehabilitation: revisited. J Sport Rehabil 1997;6:144–56. 10.1123/jsr.6.2.144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Risberg MA, Holm I, Myklebust G, et al. Neuromuscular training versus strength training during first 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther 2007;87:737–50. 10.2522/ptj.20060041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Naud S, et al. Accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind investigation evaluating knee joint laxity using roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:2536–48. 10.1177/0363546511422349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shelbourne KD, Nitz P. Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:292–9. 10.1177/036354659001800313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biggs A, Jenkins WL, Urch SE, et al. Rehabilitation for patients following ACL reconstruction: a knee symmetry model. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2009;4:2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelbourne KD, Klotz C. What I have learned about the ACL: utilizing a progressive rehabilitation scheme to achieve total knee symmetry after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sci 2006;11:318–25. 10.1007/s00776-006-1007-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelbourne KD, Vanadurongwan B, Gray T. Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using contralateral patellar tendon autograft. Clin Sports Med 2007;26:549–65. 10.1016/j.csm.2007.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman A, Chamberlain V, Railton R, et al. Extensor strength in the anterior cruciate reconstructed knee. Aust J Physiother 1995;41:83–8. 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell SM, Taylor MA. Brace-free rehabilitation, with early return to activity, for knees reconstructed with a double-looped semitendinosus and gracilis graft. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:814–25. 10.2106/00004623-199606000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelbourne KD, Klootwyk TE, Decarlo MS. Update on accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1992;15:303–8. 10.2519/jospt.1992.15.6.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson D, Samuelsson K, Karlsson J. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries with special reference to surgical technique and rehabilitation: an assessment of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 2009;25:653–85. 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Grinsven S, van Cingel RE, Holla CJ, et al. Evidence-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:1128–44. 10.1007/s00167-009-1027-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, et al. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part I: continuous passive motion, early weight bearing, postoperative bracing, and home-based rehabilitation. J Knee Surg 2008;21:217–24. 10.1055/s-0030-1247822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majima T, Yasuda K, Tago H, et al. Rehabilitation after hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;397:370–80. 10.1097/00003086-200204000-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warner SJ, Smith MV, Wright RW, et al. Sport-specific outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2011;27:1129–34. 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruse LM, Gray B, Wright RW. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:1737–48. 10.2106/JBJS.K.01246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:9–18. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00097-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine 2003;28:1290–9. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065484.95996.AF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baltaci G, Harput G, Haksever B, et al. Comparison between Nintendo Wii Fit and conventional rehabilitation on functional performance outcomes after hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:880–7. 10.1007/s00167-012-2034-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kınıklı GI, Yüksel I, Baltacı G, et al. The effect of progressive eccentric and concentric training on functional performance after autogenous hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2014;48:283–9. 10.3944/AOTT.2014.13.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sastre S, Popescu D, Núñez M, et al. Double-bundle versus single-bundle ACL reconstruction using the horizontal femoral position: a prospective, randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:32–6. 10.1007/s00167-009-0844-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vadalà A, Iorio R, De Carli A, et al. The effect of accelerated, brace free, rehabilitation on bone tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons: a CT study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:365–71. 10.1007/s00167-006-0219-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koutras G, Papadopoulos P, Terzidis IP, et al. Short-term functional and clinical outcomes after ACL reconstruction with hamstrings autograft: transtibial versus anteromedial portal technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1904–9. 10.1007/s00167-012-2323-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melikoglu MA, Balci N, Samanci N, et al. Timing of surgery and isokinetic muscle performance in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2008;21:23–8. 10.3233/BMR-2008-21103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmon LJ, Refshauge KM, Russell VJ, et al. Gender differences in outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:621–9. 10.1177/0363546505281806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treacy SH, Barron OA, Brunet ME, et al. Assessing the need for extensive supervised rehabilitation following arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. Am J Orthop 1997;26:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biernat R, Wołosewicz M, Tomaszewski W. A protocol of rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction using a hamstring autograft in the first month after surgery – a preliminary report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2007;9:178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boszotta H. Arthroscopic reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament using BTB patellar ligament in the press-fit technique. Surg Technol Int 2003;11:249–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czamara A, Królikowska A, Szuba Ł, et al. Single- vs. double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a new aspect of knee assessment during activities involving dynamic knee rotation. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:489–99. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill GN, O'Leary ST. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: the short-term recovery using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1889–94. 10.1007/s00167-012-2225-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janssen RP, van der Velden MJ, Pasmans HL, et al. Regeneration of hamstring tendons after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:898–905. 10.1007/s00167-012-2125-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaffagnini S, Grassi A, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, et al. Return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in professional soccer players. Knee 2014;21:731–5. 10.1016/j.knee.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Czaplicki A, Jarocka M, Walawski J. Isokinetic identification of knee joint torques before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144283 10.1371/journal.pone.0144283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenny JY, Clement X. Patient-based decision for resuming activity after ACL reconstruction: a single-centre experience. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2016;26:929–35. 10.1007/s00590-016-1861-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karikis I, Ahldén M, Casut A, et al. Comparison of outcome after anatomic double-bundle and antero-medial portal non-anatomic single-bundle reconstruction in ACL-injured patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:1307–15. 10.1007/s00167-016-4132-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koutras G, Bernard M, Terzidis IP, et al. Comparison of knee flexion isokinetic deficits between seated and prone positions after ACL reconstruction with hamstrings graft: Implications for rehabilitation and return to sports decisions. J Sci Med Sport 2016;19:559–62. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srinivas DK, Kanthila M, Saya RP, et al. Femoral and tibial tunnel widening following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using various modalities of fixation: a prospective observational study. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:RC09–11. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22660.8907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ali MS, Kumar A, Adnaan Ali S, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendon graft without detachment of the tibial insertion. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006;126:644–8. 10.1007/s00402-006-0128-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark RA, Howells B, Feller J, et al. Clinic-based assessment of weight-bearing asymmetry during squatting in people with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using Nintendo Wii Balance Boards. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1156–61. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Królikowska A, Czamara A, Kentel M. Does gracilis tendon harvest during ACL reconstruction with a hamstring autograft affect torque of muscles responsible for shin rotation? Med Sci Monit 2015;21:2084–93. 10.12659/MSM.893930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Åhlén M, Lidén M, Bovaller Å, et al. Bilateral magnetic resonance imaging and functional assessment of the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons a minimum of 6 years after ipsilateral harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:1735–41. 10.1177/0363546512449611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trojani C, Sané JC, Coste JS, et al. Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for ACL reconstruction in patients aged 50 years or older. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009;95:22–7. 10.1016/j.otsr.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toanen C, Demey G, Ntagiopoulos PG. Is there any benefit in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients older than 60 years? Am J Sports Med 2016;363546516678723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muller B, Bowman KF, Bedi A. ACL graft healing and biologics. Clin Sports Med 2013;32:93–109. 10.1016/j.csm.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Escamilla RF, Macleod TD, Wilk KE, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament strain and tensile forces for weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises: a guide to exercise selection. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012;42:208–20. 10.2519/jospt.2012.3768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han DL, Nyland J, Kendzior M, et al. Intratunnel versus extratunnel fixation of hamstring autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2012;28:1555–66. 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beynnon BD, Fleming BC, Johnson RJ, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament strain behavior during rehabilitation exercises in vivo. Am J Sports Med 1995;23:24–34. 10.1177/036354659502300105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nyland J, Brand E, Fisher B. Update on rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction. Open Access J Sports Med 2010;1:151–66. 10.2147/OAJSM.S9327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, et al. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part II: open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, accelerated rehabilitation, and miscellaneous topics. J Knee Surg 2008;21:225–34. 10.1055/s-0030-1247823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Fleming BC, et al. The strain behavior of the anterior cruciate ligament during squatting and active flexion-extension. A comparison of an open and a closed kinetic chain exercise. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:823–9. 10.1177/036354659702500616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janssen RP, du Mée AW, van Valkenburg J, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with 4-strand hamstring autograft and accelerated rehabilitation: a 10-year prospective study on clinical results, knee osteoarthritis and its predictors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1977–88. 10.1007/s00167-012-2234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams D, Logerstedt DS, Hunter-Giordano A, et al. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012;42:601–14. 10.2519/jospt.2012.3871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clatworthy MG, Annear P, Bulow JU, et al. Tunnel widening in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective evaluation of hamstring and patella tendon grafts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1999;7:138–45. 10.1007/s001670050138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, et al. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1543–52. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury in elite football: a prospective three-cohort study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:11–19. 10.1007/s00167-010-1170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Renström PA. Eight clinical conundrums relating to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in sport: recent evidence and a personal reflection. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:367–72. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:804–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Middleton KK, Hamilton T, Irrgang JJ, et al. Anatomic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: a global perspective. Part 1. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:1467–82. 10.1007/s00167-014-2846-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herbst E, Hoser C, Hildebrandt C, et al. Functional assessments for decision-making regarding return to sports following ACL reconstruction. Part II: clinical application of a new test battery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:1283–91. 10.1007/s00167-015-3546-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gokeler A, Welling W, Zaffagnini S, et al. Development of a test battery to enhance safe return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:192–9. 10.1007/s00167-016-4246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Claes S, Verdonk P, Forsyth R, et al. The “ligamentization” process in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: What happens to the human graft? A systematic review of the literature. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:2476–83. 10.1177/0363546511402662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]