Abstract

Introduction

Dental caries is the most prevalent childhood disease in the world and can lead to infection, pain and reduced quality of life. Multiple prevention agents are available to arrest and prevent dental caries; however, little is known of the comparative effectiveness of combined treatments when applied in pragmatic settings. The aim of the presented study is to compare the benefit of silver diamine fluoride and fluoride varnish versus fluoride varnish and glass ionomer therapeutic sealants in the arrest and prevention of dental caries.

Methods and analysis

A longitudinal, pragmatic, cluster randomised, single-blind, non-inferiority trial will be conducted in low-income rural children enrolled in public elementary schools in New Hampshire, USA, from 2018 to 2023. The primary objective is to compare the non-inferiority of alternative agents in the arrest and prevention of dental caries. The secondary objective is to compare cost-effectiveness of both interventions. Caries arrest will be evaluated after 2 years, and caries prevention will be assessed at the completion of the study. Data analysis will follow intent to treat, and statistical analyses will be conducted using a significance level of 0.05.

Ethics and dissemination

The standard of care for dental caries is office-based surgery, which presents multiple barriers to care including cost, fear and geographic isolation. The common intervention used in school-based caries prevention is dental sealants. The simplicity and affordability of silver diamine fluoride may be a viable alternative for the prevention of dental caries in high-risk children. Results can be used to inform policy for best practices in school-based oral healthcare.

Trial registration

Keywords: preventive medicine, oral medicine, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study is a cluster randomised non-inferiority trial.

Study will compare simple and complex interventions for the treatment and prevention of dental caries measured using standard clinical diagnostic criteria.

Statistical and economic analysis will use multilevel modelling, generalised additive modelling and Markov modelling.

Interventions will be randomly assigned at the school level; any child within each participating school that provides informed consent and assent will receive care twice yearly.

Background

Dental caries (tooth decay), a Gram-positive bacterial infection, is the most prevalent childhood disease in the world, estimated to cause a loss of 3.5 million disability-adjusted life years.1 2 If left untreated, dental caries can lead to acute abscess, sepsis and, in rare circumstances, systemic infection and death.3–5 Untreated dental caries affects more than 20% of elementary school-aged children in the USA, and over 50% of children have ever experienced caries. Among low-income minority children, caries experience can be greater than 70%, and the prevalence of untreated caries exceeds 30%.6–8 Though the overall prevalence of caries has reduced over the past 10 years, sealant use is lowest among low-income children, and less than half of children from low-income families reported visiting a dentist in the previous year.6 8 9

The standard of care for dental caries is office-based surgery consisting of local anaesthesia, removal of decay using a dental drill, etching of the tooth with acidic gel, application of an amalgam, composite resin, ionomer, gold or ceramic material, hardening and polishing.10 However, office-based care presents multiple access barriers to patients including cost, fear and geographic isolation.11 Fewer than 15% of children who accessed an office-based dentist received preventive care,12 many children do not have access to prevention services13 and those with the least access to prevention have a higher prevalence of oral disease.13 As a result, many federal and state organisations and institutions recommend the proactive prevention of caries as an alternative to reactive treatment.13–16 Caries prevention can be provided through traditional office-based care, mobile dental vans or as part of a school-based dental programme, and the comparative effectiveness of these prevention models has been identified as one of the highest priority research questions by the Institute of Medicine.17

Common caries prevention agents include water fluoridation, fluoride toothpaste, fluoride varnish, sealants, interim therapeutic restorations or atraumatic restorations and silver diamine fluoride (SDF). Individually, each of these preventive treatments has been shown in randomised clinical trials and systematic reviews to be efficacious in the prevention or treatment of dental caries. A review of 13 trials in children and adolescents found that those treated with fluoride varnish experienced an average reduction of decayed, missing or filled tooth surfaces of 43% when compared with untreated youth.18 A systematic review of six trials showed that resin-based sealants significantly reduced the risk of caries in permanent molars up to 48 months compared with no sealants and estimated that if 70% of control unsealed tooth surfaces were decayed, application of a resin-based sealant would significantly reduce the proportion of carious surfaces to under 19%.19 Furthermore, there was not sufficient evidence in both systematic reviews and meta-analyses to suggest the superiority of the preventive effects of either resin-based or glass ionomer sealant material.19 20 A 2012 meta-analysis of 29 studies indicated that pits and fissures of teeth sealed with interim therapeutic restorations had a mean annual caries incidence over 3 years of only 1%.21 Finally, SDF has been shown in reviews to have higher preventive fractions of arrested and prevented caries than fluoride varnish,22 and SDF at 38% concentration applied biannually was more effective in preventing caries than annual applications of lower concentrations.23

Despite this evidence, the combined effectiveness of different treatments, as well as their feasibility for use in pragmatic settings, is unknown. The objectives of the presented longitudinal, pragmatic, cluster randomised, single-blind, non-inferiority trial are to compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a simple prevention package (consisting of fluoride varnish and SDF) versus a complex prevention package (consisting of fluoride varnish and therapeutic sealants) in the arrest and prevention of dental caries among low-income rural children in primary school settings. It is hypothesised that simple caries prevention is non-inferior to complex care and is more cost-effective for large-scale implementation.

Methods/design

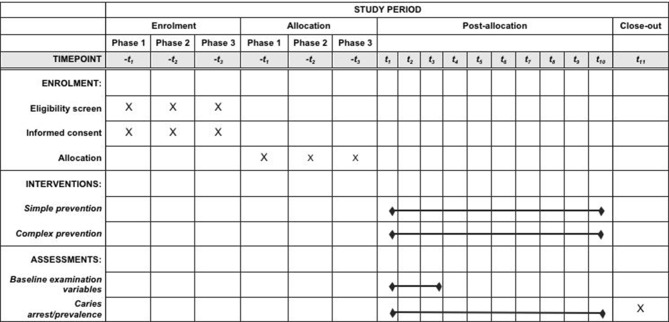

This is a longitudinal, pragmatic, cluster randomised, single-blind, non-inferiority clinical trial comparing SDF with fluoride varnish versus therapeutic sealants with fluoride varnish given biannually to children enrolled in public elementary schools in New Hampshire. Prior to the study start, participating schools meeting inclusion criteria will be randomly assigned to receive fluoride varnish/SDF or fluoride varnish/sealants in 6-month intervals (±1 month). At each observational period, study participants with informed consent will receive a comprehensive oral examination provided by a licensed dental hygienist (figure 1).24 25 The clinical examination will include an assessment of every tooth and tooth surface for decayed, filled or missing teeth, as well as pulpal involvement or abscess. Following the oral evaluation, participants will receive the assigned treatments. Any participant presenting with a medical emergency will be referred to school nurses for follow-up care.

Figure 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments.

This trial protocol is reported following the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines and has received approval from the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) (#i17-01221). Any changes to the study protocol will be communicated to the IRB and funder in quarterly reports, and investigators will cooperate with any independent audit on behalf of the IRB or funding organisation. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT03448107).

Treatment description and regimen

Simple prevention

One drop (0.05 mL) of SDF (Advantage Arrest) solution at 38% concentration (2.24 F-ion mg/dose) will be dispensed per child. Posterior tooth surfaces to be treated will be dried, after which the SDF will be applied with a microbrush to all asymptomatic carious lesions and to all pits and fissures on bicuspids and molar teeth for 30 s. Fluoride varnish (5% sodium flouride [NaF], Colgate PreviDent) will then be applied to all teeth. Simple prevention will be provided by either dental hygienists or registered nurses.

Complex prevention

All primary and permanent teeth will be dried prior to application. Pits and fissures on all bicuspids and molar teeth will be sealed with glass ionomer sealants (GC Fuji IX). Glass ionomer sealants (interim therapeutic restorations) will also be placed on all asymptomatic carious lesions. Fluoride varnish (5% NaF) will then be applied to all teeth. Complex prevention will be provided by dental hygienists.

Both arms will also receive toothbrushes, fluoride toothpaste and oral hygiene instruction. Clinical care will be provided in a dedicated room in each school using mobile equipment and disposable supplies.

Risks and adverse events

Each intervention used in this trial is currently employed in clinical practice as a standard of care procedure. The potential risks for study participants are minimal and identical to the risk for children obtaining care in a dental office. The greatest risk is an allergic reaction to fluoride varnish, SDF or glass ionomer. All adverse events occurring during the study period will be recorded: at each contact with the study participant, investigators will seek information on adverse events by specific questions and an oral examination. Evidence of adverse events will be recorded on electronic health records and appropriate case report forms. The clinical course of each event will be followed until resolution, stabilisation or until it has been determined that participation in the study was not the cause. Serious adverse events ongoing at study end will be followed to determine the final outcome. Adverse event reports will be reported to the IRB within five working days from the time investigators become aware of the event.

Definition of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Primary outcomes include clinically evaluated caries arrest and the prevention of new caries. Caries arrest will be evaluated after 2 years, and the prevalence of new caries will be evaluated after 5 years.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes include the comparative cost-effectiveness of simple versus complex prevention in the arrest and prevention of dental caries.

Recruitment and eligibility

In collaboration with the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), study investigators identified extant school-based caries prevention programmes currently operating in rural counties in New Hampshire. Programme officials were contacted to solicit interest in participating in the proposed study. Programme officials, in turn, contacted school principals to determine interest in participation. Each participating programme and school has confirmed written consent for the study.

Inclusion criteria

Any existing caries prevention programme operating in rural (defined using criteria from the US Department of Agriculture) areas, with official Title 1 status, and located in a health professional shortage area was eligible to participate. All schools within eligible programmes were eligible to participate.

Randomisation

Participating schools will be block randomised at the school level to receive either the simple or complex treatment using a random number generator. Study statisticians will generate random numbers and assign schools to each number sequence.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the treatments provided, dental hygienists and nurses providing care will not be independent from study protocols and therefore are not blinded. Assignment to treatments will follow a predetermined randomisation list at the school level, and all students with consent in participating schools will receive the assigned treatment. However, all data analyses for caries arrest will be blinded, as data will be masked prior to analysis such that which schools were assigned to each treatment cannot be determined. Following analysis of caries arrest, blinding can no longer be guaranteed.

Data collection, transmission and storage

Prior to the beginning of each school year, electronic rosters for each participating school will be provided to study investigators from the DHHS, which will include a unique student identifier, demographic variables and any available Medicaid identification. School rosters will be used to electronically create personalised informed consent forms for every student in the school, which will then be combined with a letter from the principal explaining the study and distributed to parents of children in each school. Completed informed consent will be collected at the school by study investigators. Schools will be recruited in the first year of the study. Children within schools will be enrolled in each year of the programme to accommodate newly registered students each academic year. Recruitment for this study is pending.

Data collected from each participant will be recorded on a password-protected tablet computer using a propriety software system that is prepopulated with the demographic information of the participant from previously obtained DHHS records. Data collectors will be standardised and calibrated prior to study start. Following each data collection day of the study, electronic records will be uploaded to a secure server and stored at the Boston University Data Coordinating Center (DCC) and evaluated for quality assurance. Prior to the transmission of data from the DCC to investigators, identifying information will be removed and replaced with a unique, anonymised student identifier. These data will be kept at the New York University College of Dentistry on a secure, password-protected server.

Patient and public involvement

Planning for this study began over 5 years ago with pilot studies and meetings with community stakeholders. Stakeholders included representatives from the New Hampshire DHHS Medicaid and Oral Health offices, state dental societies and insurers, community health centres and a local hospital. The study design was thus informed by stakeholder priorities and preferences, including development of protocols, selection and burden of interventions, training for hygienists and planned implementation. The design was further created with input from parents of pilot study patients who were participants in group discussions regarding prevention protocols. However, patients themselves were not directly involved.

For this study, parents will be participants in that they will sign informed consent documents. Parents of participating children will also participate in group quarterly and annual meetings. While direct study results will not be disseminated to participants, children will receive a personalised take home message after each clinical visit that summarises the care they received and the care still needed. Formal study results will be disseminated to community stakeholders.

Sample size calculation

The study is powered for the primary outcomes of caries arrest and prevention. Power calculation for caries arrest assumes a clustered two-group comparison of simple versus complex prevention for a non-inferiority trial. Estimates assume an overall participation rate of 35% across each of the two groups, yielding a total enrolment of 3926 students within 43 schools. Previous studies of school-based caries prevention in New Hampshire rural elementary schools indicated a baseline caries prevalence between 30% and 40%. Assuming an equal allocation of untreated decay across groups of 20% and alpha of 0.05, a total sample size of 198 participants per arm (n=396) would be required for a non-inferiority margin (δ) of caries arrest at 10%, assuming 80% power. When adjusted for within-school clustering (deff=10), a sample size of 3960 is required.

Power for longitudinal analyses of caries prevention was computed for the use of generalised estimating equations.26 Using the same expected enrolment of 3926 students, estimates assume an annual attrition rate of 20% and a natural increase in informed consent rates of 10% (which also includes new students entering schools and enrolling in the study) per year. For 95% power, an alpha of 0.05, an average of four observational periods (excluding baseline), a high correlation between repeated observations (r=0.6) and a design effect of 20, a sample size of 1961 students per arm is required to detect a difference in uncreated decay of 15% and 2942 for a difference of 10%.

Statistical analysis

For the non-inferiority of caries arrest, the per-patient proportion of carious lesions at baseline treated with simple versus complex prevention that stayed arrested throughout the first 2 years of observation will be determined. Any deciduous teeth with treated carious lesions that are lost due to exfoliation will be considered as arrested throughout the lifetime of the tooth, with arrested caries status being carried over throughout. Thus, tooth-level indicators are able to be present for both primary and permanent dentitions at the same time. With this approach, each carious tooth treated with either simple or comprehensive prevention is a single trial with outcomes either of arrested (1) or failed to arrest (0). The percentage of arrested caries (at the child level) will thus be modelled using multilevel binomial regression with a logit link Yj ~Bin(πj), E(Yj) = πj, where πj is the probability of success. The non-inferiority margin, δ, is set at 10%. While there is no gold standard criterion for the selection of this margin, the margin was set based on collaborative discussion with clinicians to determine what is considered as clinically unimportant. The null hypothesis is that the experimental treatment (simple prevention) is inferior to the standard treatment (complex prevention) by at least δ: πsimple − πcomplex ≥ δ. The alternative hypothesis is that πsimple − πcomplex < δ.

Based on results from multilevel binomial models, differences in effect sizes estimated by CIs will be used to determine clinical non-inferiority of the two prevention methods.27 CIs will be calculated for the difference between the two interventions, with the width of this interval signifying the extent of non-inferiority. If the difference between the two interventions lies to the right of δ, then non-inferiority will be concluded. Though this is method is preferred by reporting guidelines, p values will also be reported, in keeping with other recommendations.27

For the prevention of new caries, longitudinal data will be analysed using generalised estimating equations and multilevel mixed effects regression models with the appropriate error distribution for the prevalence and incidence of untreated caries over time. The number of teeth at risk for each child during each follow-up interval will be identified, and the number of those teeth in which new caries is observed at the examination that ends that interval will be determined. Primary teeth lost in each interval and new permanent teeth will not contribute to data for that interval. Data from baseline visits will be omitted from analyses and used as an indicator of any untreated decay at baseline.

To explore non-linear trends in untreated decay between simple and complex prevention, longitudinal data will be analysed using generalised additive models with non-parametric smoothers, linking the known known proportion Pit=E(yit=1|xijt, zit) to a non-linear non-parametric predictor using the link function where sj are smooth non-parametric functions and ui are random effects assumed to be iid ~N(0, D(ψ)).28 Heterogeneity and correlation among subjects will be accounted for through random effects.

To compare the cost effectiveness of the two included treatments, empirical results will be incorporated into a Markov decision tree, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and net health benefits will be estimated. Data for cost and health outcomes will be harvested from trees conducted for short-term (eg, the follow-up time of the presented clinical trial) and long-term (life course) time horizons. Monte Carlo simulation-based probabilistic sensitivity analyses will be used to detect the probabilities with which the two treatments represent optimum strategies. Finally, budget impact analysis will be applied to estimate expected resource implications on the population level and to determine whether and how potential cost savings could be used to increase population well-being.

Missing data will be adjusted for using multiple imputation and inverse probability weighting. Statistical analysis will be performed following intention-to-treat and analysed using Stata V.15.0 and R V.3.1.1.

Ethics and dissemination

Persistent unmet oral health needs in low-income and minority populations stem from an inability to access or afford traditional, office-based dental care. The Institute of Medicine ‘envisions oral health care in the United States in which everyone has access to quality oral care across the life cycle’, which requires a collaborative effort across health systems to eliminate the health barriers contributing to oral diseases and prioritise disease prevention.29 In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend school-based sealant programmes, noting that a large proportion of low-income children do not have access to dental sealants.30 Simultaneously, the use of SDF to arrest and prevent dental caries is growing.31 32 Two added benefits in using SDF in school-based prevention programmes are that they are faster to provide than sealants and are less costly. Thus, if SDF is shown to be non-inferior to sealants in the arrest and prevention of dental caries, it can be used as an alternative intervention for school-based caries prevention with potentially broader impact.

The direct benefit anticipated for participating children is improved oral health. Due to the minimally invasive nature of experimental interventions, no additional risks are expected. Demonstrating the non-inferiority of SDF to traditional and therapeutic sealants in the arrest and prevention of dental caries in a pragmatic, school-based setting will yield objective data on the practical effectiveness of an efficient, cost-effective caries prevention agent in high-risk populations. Results from testable hypotheses can thus be used to encourage policy change to expand school-based health services to include caries prevention.

Trial status

Protocol version 1.0 (30 November 2017). Recruitment will begin August 2018. Recruitment will be on a rolling, semester-by-semester basis and will conclude June 2023. This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (registration #NCT03448107, registered 26 February 2018).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient and stakeholder partners who have assisted in the design and development of this trial.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors are the study principal investigators. Both authors participated in study conception and design and contributed to the writing of the study protocol. Both authors drafted and edited the trial protocol. RRR carried out all statistical analyses. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research is supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD011526) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: This study received approval from the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (approved 3 October 2017; #i17-00578). All students in participating schools will be invited to participate and parents will sign a consent form after reviewing written information about the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1. Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, et al. . Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res 2013;92:592–7. 10.1177/0022034513490168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, et al. . Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res 2017;96:380–7. 10.1177/0022034517693566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robertson D, Smith AJ. The microbiology of the acute dental abscess. J Med Microbiol 2009;58:155–62. 10.1099/jmm.0.003517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pine CM, Harris RV, Burnside G, et al. . An investigation of the relationship between untreated decayed teeth and dental sepsis in 5-year-old children. Br Dent J 2006;200:45–7. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooke B. The prevention of dental caries and oral sepsis. Probe 1970;13:83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dye BA, Li X, Thorton-Evans G. Oral health disparities as determined by selected healthy people 2020 oral health objectives for the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012;104:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, et al. . Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2015;191:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffin SO, Wei L, Gooch BF, et al. . Vital signs: dental sealant use and untreated tooth decay among U.S. school-aged children. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1141–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6541e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G. Trends in oral health by poverty status as measured by Healthy People 2010 objectives. Public Health Rep 2010;125:817–30. 10.1177/003335491012500609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Preparation of cavities for fillings : Webster AE, Johnson CN, A text-book of operative dentistry. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vujicic M, Nasseh K. A decade in dental care utilization among adults and children (2001-2010). Health Serv Res 2014;49:460–80. 10.1111/1475-6773.12130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin SO, Barker LK, Wei L, et al. . Use of dental care and effective preventive services in preventing tooth decay among U.S. Children and adolescents--Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, United States, 2003-2009 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005-2010. MMWR Suppl 2014;63:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. A national call to action to promote oral health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. . Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11 2007;11:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, et al. . Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2015:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Office USGA. Oral Health: efforts under way to improve children’s access to dental services, but sustained attention needed to address ongoing concerns: United States Government Accountability Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. IOM. Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marinho VC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, et al. . Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD002279 10.1002/14651858.CD002279.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Forss H, Walsh T, et al. . Sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD001830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yengopal V, Mickenautsch S, Bezerra AC, et al. . Caries-preventive effect of glass ionomer and resin-based fissure sealants on permanent teeth: a meta analysis. J Oral Sci 2009;51:373–82. 10.2334/josnusd.51.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Amorim RG, Leal SC, Frencken JE. Survival of atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) sealants and restorations: a meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2012;16:429–41. 10.1007/s00784-011-0513-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenblatt A, Stamford TC, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride: a caries "silver-fluoride bullet". J Dent Res 2009;88:116–25. 10.1177/0022034508329406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhi QH, Lo EC, Lin HC. Randomized clinical trial on effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and glass ionomer in arresting dentine caries in preschool children. J Dent 2012;40:962–7. 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Broder HL, Wilson-Genderson M. Reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the Child Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP Child’s version). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;35(Suppl 1):20–31. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.0002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Broder HL, Wilson-Genderson M, Sischo L. Reliability and validity testing for the Child Oral Health Impact Profile-Reduced (COHIP-SF 19). J Public Health Dent 2012;72:302–12. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00338.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Kung-Yee L, et al. . Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greene CJ, Morland LA, Durkalski VL, et al. . Noninferiority and equivalence designs: issues and implications for mental health research. J Trauma Stress 2008;21:433–9. 10.1002/jts.20367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sapra S. Semi-parametric mixed effects models for longitudinal data with applications in business and economics. International Journal of Advanced Statistics and Probability 2014;2:84 10.14419/ijasp.v2i2.3624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable and underserved populations. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gooch BF, Griffin SO, Gray SK, et al. . Preventing dental caries through school-based sealant programs: updated recommendations and reviews of evidence. J Am Dent Assoc 2009;140:1356–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Llodra JC, Rodriguez A, Ferrer B, et al. . Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for caries reduction in primary teeth and first permanent molars of schoolchildren: 36-month clinical trial. J Dent Res 2005;84:721–4. 10.1177/154405910508400807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horst JA, Ellenikiotis H, Milgrom PL. UCSF Protocol for Caries Arrest Using Silver Diamine Fluoride: Rationale, Indications and Consent. J Calif Dent Assoc 2016;44:16–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.