Abstract

Objective

The present study aims to elucidate the state of gender equality in high-quality dermatological research by analysing the representation of female authorships from January 2008 to May 2017.

Design

Retrospective, descriptive study.

Setting

113 189 male and female authorships from 23 373 research articles published in 23 dermatological Q1 journals were analysed with the aid of the Gendermetrics Platform.

Results

43.0% of all authorships and 50.2% of the firstauthorships, 43.7% of the coauthorships and 33.1% of the last authorships are held by women. The corresponding female-to-male ORs are 1.41 (95% CI 1.37 to 1.45) for first authorships, 1.07 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.10) for coauthorships and 0.60 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.62) for last authorships. The annual growth rates are 1.74% overall and 1.45% for first authorships, 1.53% for coauthorships and 2.97% for last authorships. Women are slightly under-represented at prestigious authorships compared with men (Prestige Index=−0.11). The under-representation remains stable in highly competitive articles attracting the highest citation rates, namely, articles with many authors and articles that were published in highest-impact journals. Multiauthor articles with male key authors are only slightly more frequently cited than those with female key authors. Women publish slightly fewer papers compared with men (47.2% women hold 43.0% of the authorships). At the level of individual journals, there is a high degree of uniformity in gender-specific authorship odds. By contrast, distinct differences at country level were revealed. The prognosis for the next decades forecasts a consecutive harmonisation of authorship odds between the two genders.

Conclusions

In high-quality dermatological research, the integration of female scholars is advanced as compared with other medical disciplines. A gender gap consists mainly in the form of a career dichotomy, with many female early career researchers and few women in academic leadership positions. However, this gender gap has been narrowed in the last decade and will likely be further reduced in the future.

Keywords: odds ratio, prestige, citations, productivity, career

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Gendermetrics Platform is a well-established system to analyse gender disparities in science by considering the gender-specific distribution of first authorships, coauthorships and last authorships.

The purely bibliometric and algorithmic approach allows analyses of large volumes of data standardised and independent of the examiner, and thus with a minimised interindividual variability.

Our analysis is limited by the absence of information concerning equally distributed authorships, corresponding authors as well as data providing information about the scholar’s academic degree, their position, age, employment status and their participation on editorial boards.

The investigation period is technically limited to articles that are published after 2006 due to the predominance of initials preventing a correct gender identification by first names in older articles.

Introduction

The past decades have seen an enormous increase in the number of women entering medicine.1 While in 1969, 6.9% of the US medical graduates were women, the percentage reached a value of 47.5% in 20 14.2 The enrolment in the US medical school in 2016 was almost evenly divided between women (49.8%) and men (50.2%).3 Despite this enormous increase of women entering the field of medicine, ’across medicine and dermatology, this influx has not been accompanied by a parallel progress by female faculty with academic credentials or in leadership roles’, as stated by an editorial of Alexa Kimball4 and many articles have addressed different gender and generational aspects in academic dermatology in the past years.5–9 In 2012, Sadeghpour et al published results from a national survey on the role of gender in academic dermatology.1 They assessed whether there is an association between gender and academic rank. They came to the conclusion that gender-based differences in academic dermatology, including career track, academic rank distribution, leadership and career satisfaction, persist.1 Of a total of 259 full-time US academic dermatologists (38.6% were female), they found that men held more senior positions even after adjustment for age and number of years since completion of residency.1 Working hours did not differ significantly. While most men (90.3%) and women (82.8%) were satisfied with their career, women were 24.6% more likely than men to consider leaving academia.1 In line with these findings, Shi et al conducted in 2017 a cross-sectional observational study of dermatology departments and divisions in the USA revealing that women account for 47.9% of dermatology residency programme directors but comprise only 23.5% of chairpersons/chiefs.10 Another recent study investigates the influence of women in academic dermatology by assessing the number of women acting as editors-in-chief of prominent dermatology journals.11 The study revealed that there have been 26 female editors and at least 128 male editors in the considered 25 dermatology journals and that 45.8% of journals have not yet had a female editor.11 Moreover, the study clearly showed that in the last decades there has been an increase in the number of women holding these prestigious positions.

As stated previously, an indicator for the balance between integration of female and male dermatologists and scientists is the quantification of their scholastic activity as represented by ‘authorship’ in scientific publications.12–15 In general, authorships represent the currency system of research and academic community.16 In original medical articles, the assignment of authorship follows, by convention, the rule that ‘the first author indicates the person whose work underlies the paper as a whole',17 whereas the last authorship ‘indicates a person whose work or role made the study possible without necessarily doing the actual work’.17 Thus, the assignment of authorships differs considerably from, for example, economics or mathematics, where authors are usually listed in alphabetical order.16 One consequence is that an early career researcher normally publishes as first or coauthor, whereas a senior researcher prefers the last author position in original research articles.18 19 A further consequence of this assignment rule is that the different types of authorships are associated with different prestige. Specifically, first and last authorships have a significantly higher reputation than coauthorships.18

Based on these consideration, we here applied the recently established Gendermetrics Platform20 to analyse the integration of women in high-quality dermatological research by assessing 113 189 male and female authorships (FAP) from 23 dermatological Q1 journals.

Conceptually, we determined the proportion of female first authorships, coauthorships and last authorships and quantified the relative distribution of FAP among the different authorships compared with men by applying ORs. Moreover, we used the Prestige Index to analyse the distribution of prestigious authorships between the two genders. The analysis includes global status and temporal development, differences across countries and the role women tend to have in articles with many authors, for example, collaboration on articles.14 Moreover, a gender-specific analysis of scholarly productivity and citation rate was conducted. The study concludes with a 10-year forecast regarding the development of gender disparities in the field of high-quality dermatological research.

Methods

Data acquisition and integration

The data analysis was conducted using Gendermetrics.NET,20 a SQL-Server-based platform for analysing bibliometric data with a special emphasis on gender aspects. Research articles from high impact dermatology journals listed in the Scimago Journal & Country Rank database (http://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=2708) were acquired on 15 May 2017 from the Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters). The journals constitute the subset of dermatological Q1 journals in 2016 representing the top 25% of the corresponding impact factor distribution. The journals 'Fibrogenesis and Tissue Repair', 'Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology' and 'Dermatology and Therapy' were not considered because there were not indexed in the Web of Science database. The journals ’Aids Research and Treatment', 'BMC Dermatology', 'Clinics in Dermatology', 'Dermato-Endocrinology' and 'HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care' were excluded from analysis due to a low number of articles (<200 articles). Furthermore, the journals 'British Journal of Dermatology' and ’Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology' had to be excluded from analysis due to the predominant usage of initials instead of full first names, which prevents the correct gender determination. In total, 23 of the 33 dermatological Q1 journals with 23 373 articles written by 74 354 authors remain for analysis.

Gender determination

The algorithmic gender determination operates on the basis of a data table containing the gender of 77 818 forenames (male, female or unisex).20 By applying the algorithm, 30 538 (=41.1%) male authors, 27 261 (=36.7%) female authors, 5509 (=7.4%) unisex authors and 11 046 (=14.9%) undefined authors were determined with a relatively little interannual variability (see online supplementary figure 1). The unisex and undefined authors and their authorships were not taken into consideration (in total 27 182 authorships). As a result, 113 189 male authorships and FAP affiliated to institutions from 150 countries were analysed. The research output of a country was thereby benchmarked by considering the authorships of the related institutions.14 It is important to note that the quality of gender detection depends on the authorships country as illustrated by online supplementary figure 2. In order to ensure the validity of the country-specific analysis, we set a threshold criterion for the country-specific analysis (see online supplementary figure 2), as recently described by Bendels et al.20 In particular, only countries with a detection rate of at least 79.3% male authorships or FAP were considered. As a result, among the top 20 most productive countries, the Asian countries China, South Korea (with high rates of unisex names) and India (with many undefined names) were excluded. A bibliometric overview is given in online supplementary figure 3.

bmjopen-2017-020089supp001.pdf (953.8KB, pdf)

Proportion of female authorships and female authorship odds ratio

In this study, first authorships, coauthorships and last authorships were considered, whereby coauthorships encompasses all authorships between one first authorship and one last authorship. Equally distributed authorships were not considered due to a lack of information. The proportion of FAP is defined as the quotient between the FAP count and the total sum of male authorships and FAP. The FAP is presented as a percentage to improve the textual readability. The female to male ORs for first authorships, coauthorships and last authorships were determined (female authorship odds ratio (FAOR)) with the corresponding CIs at a confidence level of 95%.14 The FAOR measures the female odds of securing a particular authorship type compared with men. An FAOR of 2.0 or 0.5 means that women or men, respectively, have twice the odds of holding a particular authorship compared with respective other gender.14 For a simplified representation, a triplet is used to indicate the sign of the significant female OR excess to get a particular authorship. For example, the FAOR-triplet (−, =, +) indicates that women have significantly lower ORs for first authorships, equal ORs for coauthorships and significantly higher ORs for last authorships compared with men.14 In summary, the FAP measures the quantitative representation of FAP, whereas the FAORs quantify the relative distribution of FAP among the different authorships.14 To increase the statistical significance, the FAP/FAOR classification is only conducted for subjects (eg, countries, journals) with at least 750 male authorships or FAP.

Prestige Index

The Prestige Index measures the female odds of holding prestigious authorships compared with men.14 It is defined as the prestige-weighted average of the FAOR excess εt that is calculated over all authorship types t (ie, for first authorships, coauthorships and last authorships), εt = wt (FAORt–1), if FAORt≥1, otherwise εt=wt(1–1/FAORt) with the weighting factor wt.14 In medical science, the prestige of scholarships follows a ranked order with a higher reputation of first and last authorships and a lower reputation of coauthorships.18 Specifically, a potentially alphabetical ordering of the author list was excluded by an additional test (online supplementary figure 4). Therefore, coauthorships were weighted negatively (wco=–1), whereas first authorships and last authorships were weighted positively (wfirst=wlast=1).14 This definition implies that the Prestige Index is lowered by both higher odds for coauthorships and lower odds for first and last authorships. A value of 0 characterises a balanced distribution of prestigious authorships between the two genders, whereas a value above (below) 0 indicates an excess (lack) of prestigious authorships held by women.

Analysis of data

Average annual growth rates (AAGR) were applied to characterise annual growth rates.14 The AAGRs of both, FARs and number of authorships were used to make a linear prognosis of the temporal development of FAP, FAOR and Prestige Index for the coming decade. The Pearson’s correlation was applied to evaluate the linear association between the FAP, the Prestige Index and the journals' mean impact factor. The latter was calculated over the years 2008 to 2016/2017. The null hypothesis, whether the non-normally distributed gendered citation rates (see online supplementary figure 5) stem from the same distribution, was tested by a Kruskal-Wallis test and a post hoc multicomparison test. The significance threshold was set at 0.05.

Patient and public involvement statement

No patients were involved in the study.

Results

Female authorships on a global level

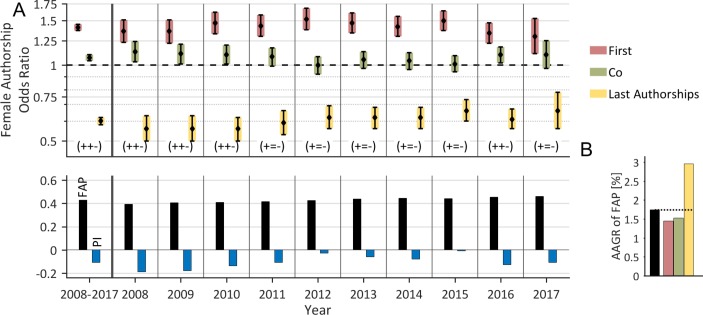

In a first step, we analysed the representation of FAP on a global level. The analysis reveals an under-representation of FAP 43.0% (figure 1A, bottom), relatively more first authorships (50.2%), an almost equal proportion of female coauthorships (43.7%) and a substantially less fraction of last authorships (33.1%). The corresponding FAORs (figure 1A) are 1.41 (95% CI 1.37 to 1.45) for first authorships, 1.07 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.10) for coauthorships and 0.60 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.62) for last authorships. The differences are statistically significant (P<0.05) for all types of authorships between the two genders. Thus, the global FAOR-pattern is characterised by the FAOR-triplet (+, +, −), that is, women have significant higher odds for first authorships and coauthorships and significant lower odds for last authorships. The Prestige Index is on average −0.11, indicating a minor lack of prestigious authorships held by women (figure 1A, bottom).

Figure 1.

Time trend of female authorships (FAP) on the global level. (A) The relative frequency of FAP (bottom), the pattern of female authorship odds ratios (FAORs) (with FAOR-triplet, top) and its associated Prestige Index (PI) are depicted by year and averaged over time. The averaged FAOR distribution is characterised by the FAOR-pattern (+, +, −), ie, women have significantly higher odds for first authorships and coauthorships and significantly lower odds for last authorships. The slightly negative PI indicates a lack of prestigious authorships held by women. (B) The FAP exhibits a relatively high increase as documented by its average annual growth rate (AAGR) of 1.74% per year with the highest rate for last authorships (2.97%). Overall, this led to more gender neutrality in authorships odds during the recent years.

The FAP exhibits a relatively high increase over the evaluation period (39.5% in 2008, 46.1% in 2017, figure 1B) with an AAGR of 1.74%. The subanalysis reveals a disproportionally high annual growth for last authorships (2.97%) and disproportionally low values for coauthorships (1.53%) and first authorships (1.45%). Overall, this led to more gender-neutrality in authorships odds during the recent years, as also indicated by the Prestige Index (−0.19 in 2008 and −0.11 in 2017).

Differences across countries

When we refined our analysis from global to country-specific level, we identified among the most productive countries a wide range of FAPs that extent from 66.7% in Finland to 25.3% in Japan (table 1). Different FAOR-patterns were identified ranging from unfavourable with the FAOR-triplet (=, +, −) identified in Poland, Italy and Spain to favourable with the FAOR-triplet (+, −, =) in Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands (table 1). Israel provides gender-neutrality with respect to all authorships (FAOR-triplet (=, =, =)). The majority of the countries exhibit FAOR-patterns that are characterised by lower female odds for last and higher female odds for first authorships compared with men. Remarkably, there is not a single country where women have currently higher odds for a last authorship compared with men.

Table 1.

Country classification

| Country name | Female authorship ratio (%) |

FAOR-triplet | Prestige Index | #Articles | #Authorships |

| Denmark | 43.4 | (+, −, =) | 0.60 | 637 | 2392 |

| Finland | 66.7 | (+, −, =) | 0.54 | 177 | 787 |

| The Netherlands | 44.8 | (+, −, =) | 0.42 | 941 | 3400 |

| Brazil | 56.1 | (+, −, −) | 0.14 | 959 | 4141 |

| Turkey | 45.2 | (+, =, =) | 0.08 | 518 | 1930 |

| Sweden | 53.7 | (+, =, −) | 0.07 | 630 | 2118 |

| Israel | 38.3 | (=, =, =) | −0.01 | 331 | 1032 |

| Canada | 42.1 | (+, =, −) | −0.04 | 816 | 2160 |

| Germany | 37.6 | (+, =, −) | −0.09 | 2498 | 10 438 |

| Australia | 42.6 | (+, =, −) | −0.10 | 817 | 3016 |

| USA | 42.9 | (+, +, −) | −0.14 | 8391 | 33 510 |

| Belgium | 51.2 | (+, =, −) | −0.16 | 378 | 1001 |

| France | 48.9 | (+, =, −) | −0.17 | 1171 | 5566 |

| UK | 45.8 | (+, +, −) | −0.18 | 1751 | 4825 |

| Switzerland | 34.3 | (+, =, −) | −0.26 | 560 | 1659 |

| Poland | 54.2 | (=, +, −) | −0.39 | 257 | 967 |

| Italy | 54.2 | (=, +, −) | −0.46 | 1269 | 6455 |

| Spain | 48.8 | (=, +, −) | −0.50 | 711 | 3073 |

| Japan | 25.3 | (+, +, −) | −0.51 | 1564 | 8126 |

| Austria | 38.6 | (+, +, −) | −0.58 | 475 | 1760 |

Countries are descendingly ordered by their Prestige Index. The number of considered male and female authorships is given by #Authorships.

When considering the distribution of prestigious authorships, we found countries with very high Prestige Indices, like Denmark (Prestige Index=0.60), Finland (0.54) and the Netherlands (0.42). In these countries, women have higher odds to hold a prestigious authorship compared with men. By contrast, Italy (Prestige Index=−0.46), Spain (−0.50), Japan (−0.51) and Austria (−0.58) are characterised by a lack of prestigious authorships held by women. Remarkably, we found no significant correlation between the FAP of a country and its Prestige Index (r(18)=0.36, P>0.05).

Differences across journals

At the level of individual journals, the FAP ranges from 53.4% in Sexually Transmitted Diseases to 32.9% in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine (table 2). The predominant FAOR-pattern is characterised by the FAOR-triplet (+, =, −). Moreover, in almost all journals (with the exception of Contact Dermatitis), women have significant lower odds for last authorships. Furthermore, in our analysis, there is no journal, where a) male scholars have significantly higher odds for first authorships compared with their female counterparts and b) where women have higher odds to secure last authorships than men.

Table 2.

Journal classification

| Journal name | Mean impact factor 2008–2016 |

Female authorship ratio (%) |

FAOR-triplet | Prestige Index | #Articles | #Authorships |

| Contact Dermatitis | 3.85 | 49.5 | (+, −, =) | 0.19 | 721 | 3623 |

| Acta Dermato-Venereologica | 3.27 | 47.4 | (+, =, −) | 0.11 | 834 | 4749 |

| Sexually Transmitted Infections | 2.88 | 50.1 | (+, =, −) | 0.06 | 1110 | 4369 |

| Wound Repair and Regeneration | 2.80 | 38.1 | (+, =, −) | 0.03 | 847 | 4354 |

| Journal of Dermatological Science | 3.54 | 33.4 | (+, =, −) | 0.03 | 727 | 3763 |

| Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology | 4.83 | 44.9 | (+, =, −) | −0.01 | 2103 | 11 338 |

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases | 2.78 | 53.4 | (+, =, −) | −0.05 | 1370 | 7500 |

| Journal of Investigative Dermatology | 6.26 | 42.1 | (+, =, −) | −0.06 | 2392 | 16 865 |

| Lasers in Medical Science | 2.29 | 40.1 | (+, =, −) | −0.1 | 1550 | 6130 |

| American Journal of Clinical Dermatology | 2.16 | 47.5 | (+, =, −) | −0.13 | 263 | 981 |

| Melanoma Research | 2.29 | 44.6 | (+, =, −) | −0.14 | 616 | 3845 |

| Dermatologic Surgery | 2.04 | 35.9 | (+, =, −) | −0.16 | 1715 | 6473 |

| Archives of Dermatological Research | 2.19 | 41.6 | (+, =, −) | −0.16 | 799 | 3355 |

| Lasers in Surgery and Medicine | 2.67 | 32.9 | (+, =, −) | −0.17 | 938 | 4161 |

| Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research | 4.91 | 42.9 | (+, =, −) | −0.18 | 510 | 3199 |

| Experimental Dermatology | 3.45 | 41.9 | (+, +, −) | −0.19 | 1644 | 8732 |

| International Wound Journal | 1.99 | 37.1 | (=, +, −) | −0.21 | 891 | 3877 |

| JAMA Dermatology | 5.46 | 47.2 | (+, +, −) | −0.27 | 491 | 3163 |

| Journal of Dermatological Treatment | 1.65 | 45.1 | (+, +, −) | −0.3 | 655 | 2590 |

| Dermatologic Clinics | 1.74 | 47.3 | (+, +, −) | −0.35 | 569 | 1205 |

| Clinics In Dermatology | 2.40 | 43.6 | (=, +, −) | −0.39 | 743 | 1732 |

| Mycoses | 1.81 | 47.0 | (=, +, −) | −0.41 | 974 | 3710 |

| Dermatology | 2.06 | 41.7 | (+, +, −) | −0.5 | 911 | 3475 |

Journals are descendingly ordered by their Prestige Index.

The Prestige Index value range is from −0.50 to 0.19 (table 2). Best odds for women to secure prestigious authorships are given in Contact Dermatitis (Prestige Index=0.19) and Acta Dermato-Venereologica (0.11), whereas Dermatology (−0.5) and Mycoses (−0.41) provide best odds for male scholars. We found no significant correlation between the a) FAP of the journal and its mean impact factor (r(21)=0.08, P>0.05), b) the Prestige Index and the mean impact factor (r(21)=0.37, P>0.05) and c) the FAP and the Prestige Index (r(21)=0.08, P>0.05).

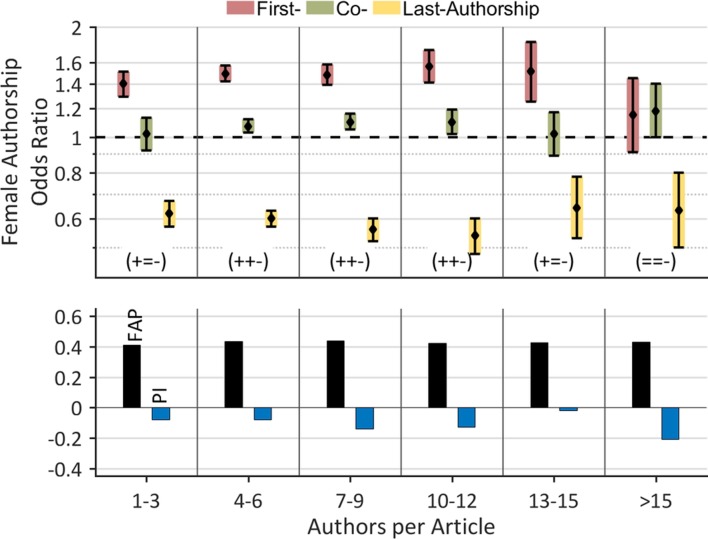

Female authorships by authors per article

We also assess the role women tend to have in articles with many authors, for example, collaborative articles. The FAP fluctuates between 40.9% (one to three authors/article) and 43.7% (seven to nine authors/article) and exhibits no significant correlation to the number of authors per article. Although the FAORs for first authorships and last authorships have the tendency to slightly increase and decrease, respectively, with an increasing number of authors, this trend is reversed for higher author rates (>12 authors/article) (figure 2). In addition, the FOAR for coauthorships shows no significant relationship to the author rate. As a consequence, the Prestige Index fluctuates between −0.02 (13–15 authors/article) and −0.21 (>15 authors/article). To summarise, FAP, FAORs and Prestige Index show no clear correlation to the number of authors per article.

Figure 2.

Female authorships (FAP) by authors per article. Although the female authorship odds ratios (FAORs) for first authorships and last authorships have the tendency to slightly increase and decrease, respectively, with an increasing number of authors, this trend is reversed for higher author rates (>12 authors/article). FAP, FAORs and Prestige Index (PI) show no clear correlation to the number of authors per article.

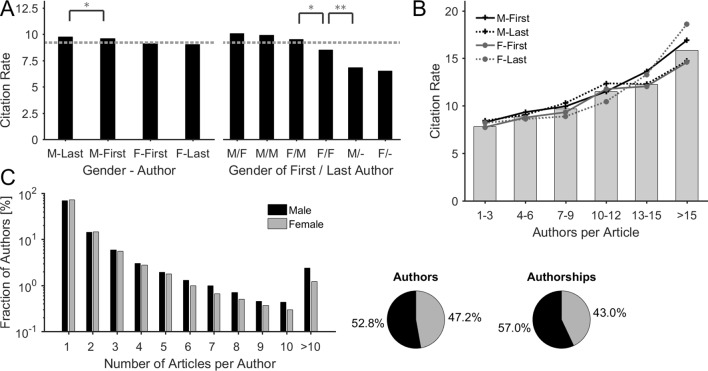

Citation and productivity analysis

The analysis reveals that articles with male key authors are more frequently cited than articles with female authors (figure 3A). However, the differences are very low as articles with a male last or first author have average citation rates of 9.7 citations/article and 9.6 citations/article, respectively and articles with a female first or last author exhibit citation rates of 9.1 citations/article and 9.0 citations/article, respectively. Statistically significant differences in the distributions of citation rates were only found between articles with male last authors and all other article groups (Kruskal-Wallis test, P<0.05). Articles with a female first or last authorship were on average below the mean citation rate of 9.2 citations/article.

Figure 3.

Gender specificity of citations and scholarly productivity. (A) The descendingly ordered citation rates show that articles with male key authorships are slightly more frequently cited than articles with female key authorships. The mean citation rate of 9.2 citations/article is depicted by a dotted line (Kruskal-Wallis test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (B) Average citation rates of ungrouped articles (bars) and articles that were grouped by the gender of their key authorships (lines), depicted as a function of the number of authors. Statistically, the citation rate of an article is higher the more authors are involved. The gender-specific differences in citation rates are not preserved across the different levels of author count. (C) Gender-specific distribution of the article count per author. Women dominate the subgroups ’author has one or two article(s)'. All other subgroups are characterised by a relatively over-representation of male authors. This finding correlates with the higher productivity of male authors, as 52.8% male authors are responsible for 57.0% of all authorships.

The analysis of combined authorships shows that male-first/female-last and male-first/male-last articles have on average the highest citation rates with 10.1 citations/article and 9.9 citations/article, respectively, followed by female-first/male-last (9.5 citations/article) and female-first/female-last (8.5 citations/article) articles (figure 3A, right). Single-authored articles have the lowest citation rates with slightly higher citation rates for male-authored articles (6.8 citations/article vs 6.5 citations/articles).

The analysis further demonstrates that statistically the citation rate of an article gets higher the more authors are involved, for example, articles with 1–3 authors are on average cited 7.8 times, whereas articles with >15 authors are cited 15.9 times on average (figure 3B). Furthermore, the revealed differences in the citation rates between articles with male or female key authors are not preserved when articles are grouped by the length of their author list, as shown by figure 3B. In this grouping scheme, articles with female last authors and >15 authors attract the highest citation rates of on average 18.6 citations per article.

Considering the gender-specific distribution of the article count per author, we found that the subgroups ’author of 1 article' and ’author of 2 articles' are relatively dominated by women. In particular, 71.5% of the female authors, but only 68.1% of the male authors had published a single article in our data set (figure 3C). By contrast, all other subgroups with three or more articles per author show a relative over-representation of male authors. Particularly, the subgroup of most productive authors (’author of >10 articles') is considerably dominated by men (2.4% of the male authors vs 1.2% of the female authors). This finding results in a slightly higher productivity of male authors, as 53.0% of male authors hold 57.0% of all authorships (figure 3C).

Discussion

Advanced integration of women

The field of high-quality dermatological research is characterised by a moderate under-representation of FAP of 43.0%. This value is considerably higher than the previously determined FAPs, which were found for the whole area of science (30%),13 for six high-quality medical journals (34%)21 and for similar studies from the research fields of epilepsy (39.4%),14 schizophrenia (37.6%),12 stroke research (36.3%, unpublished data) and lung cancer research (31.3%)22 (see table 3).

Table 3.

Synopsis of different subject areas

| Subject area | FAP (%) | FAOR first | FAOR co | FAOR last |

Prestige

Index |

Female representation at prestigious authorships in | Gender-specific differences in citation rates | |

| Multiauthor articles | Highest impact journals | |||||||

| Q1 Dermatology | 43.0 | 1.41 | 1.07 | 0.60 | −0.11 | Stable | Stable | Minor |

| Epilepsy14 | 39.6 | 1.25 | 1.17 | 0.57 | −0.22 | Decline | - | Major |

| Schizophrenia12 | 37.6 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 0.57 | −0.22 | Sharp decline | - | Major |

| Lung Cancer22 | 31.3 | 1.22 | 1.19 | 0.59 | −0.22 | Sharp decline | - | Minor |

| Nature Index Journals35 | 29.8 | 1.19 | 1.35 | 0.47 | −0.42 | Sharp decline |

Decline | Major |

In high-quality dermatological research, the integration of female scholars is advanced as compared with other (medical) disciplines. However, in all subject areas, a considerable career dichotomy is still present, with many female researchers at the beginning of their career and few women in academic leadership positions. Please note that the Nature Index offers a database for the specific analysis of high impact scientific efforts from the journal categories of Multidisciplinary, Earth & Environmental, Life Science and Physics 46 (Physics was excluded from analysis).

Female scholars are inhomogeneously distributed across the different authorships: we found many female first authorships and a significantly lower proportion of female last authorships. Evidently, this finding illustrates the well-known, gender-specific career dichotomy as first authorships or coauthorships are usually held by early career researchers, whereas last authorships are regularly preserved for institutional heads or principal investigators.18 Such a discrepancy in leadership positions has been described for the most scientific disciplines,13 including various medical research fields.1 12 14 23–26 What are the reasons for such a striking career dichotomy between the two genders? Differences in career preferences between men and women are one reason that can be cited in this regard.27 Specifically, it has been shown that men were more likely to occupy investigative career tracks (26.5% vs 11.1%), whereas women predominantly occupied clinical educator tracks (81.5% vs 50.0%) in the US dermatology.1 Other reasons include altered life priorities like family planning,13 the lack of role models,26 an insufficient work-life balance,26 women’s increased likelihood to occupy part-time positions1 and the consistently high influx of female medical students and graduates.26

Interestingly, low female odds for last authorships are numerically compensated by high female odds for first authorships. This constellation leads to an almost gender neutral distribution of prestigious authorships on the global level. This finding is important, since academic publishing at prestigious authorships is one of the core elements of career advancement in science.12 28–30 However, the under-representation of last authorships potentially reduces the further career advancement of the female scientists,31 since last authorships are often taken as a major indicator of successful leadership, for example, by committees making this a criterion in granting and hiring.18 In line with this, a cross-sectional survey from 2009 revealed a clear gender difference in academic senior ranks of the US dermatologists, as it was reported that ’women were predominantly at the assistant professor level (50.0%) compared with men (24.3%), whereas men were predominantly at the full professor level (47.4%) compared with women (14.9%)'.1 Evidently, in dermatology, the proportion of female faculty members declined as academic rank increased.

Stable representation of women in multiauthor articles results in almost gender-neutral citation rates

Remarkably, we found no significant relationship between the representation of FAP and the number of authors per article. Specifically, the representation of FAP remains also stable for articles with high numbers of authors (eg, collaboration articles), which statistically attract the highest citation rates (figure 3B).32 This is an important result, since it provides a good explanation for the almost equal citation rates of articles that were grouped by the gender of their keys authors. This is particularly remarkable, since for all other disciplines we have examined so far, we find a) an accentuating under-representation of women at prestigious authorships with an increasing number of authors per article and b) significantly higher citation rates of articles with male key authors. Moreover, previous studies from various disciplines also reported about substantially higher citation rates for articles with male key authors.13 29 31 33–35 To summarise, well-balanced citation rates between the two genders suggest that the integration of women in dermatological science is well-advanced. Methodically, it is important to note that the determined citation rates describe essentially the situation from the early phase of investigation (2008–2010), since older articles have a stronger impact on the citation statistics than newer articles (‘Cited Half-Life’).36

Structural position affects productivity

The lower productivity of female scholars (47% female authors hold 43% of the authorships) is in line with reports from other scientific fields and medical disciplines.12–14 23–25 37 Interestingly, we were able to reproduce the clear male over-representation at levels of higher productivity (figure 3C), as already shown for the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology,34 the medical research fields of schizophrenia12 and epilepsy14 and for the field of high-quality research from the areas Life Science, Earth & Environmental, Multidisciplinary and Chemistry.35 It is reasonable to assume that the primary factors affecting women’s productivity are not higher rejection rates as explicitly shown for the journals Cortex 38 and Nature Neuroscience,39 but rather, due to the position of women within the scientific system.28 35 In practice, the mainly male senior scientists are often associated with more or less fruitful (citation) networks, whereas ‘women are more likely to work as adjuncts or at teaching-intensive institutions with limited resources’.28 This assumption is confirmed by a previous study by Sadeghpour et al 1 documenting no differences in the number of publications of full-time academic dermatologists after adjustment for academic rank. Moreover, it has been shown by Reed et al 37 that women’s publication rates start to increase later in their career.

Distinct regional differences

Apart from these global findings, distinct regional differences were found with best-balanced authorship odds between the two genders in Israel (FAOR-triplet (=, =, =), Prestige Index=−0.01). When taking the chance of holding a prestigious authorship as a general surrogate parameter for career advancement in science,14 Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands provide the best conditions for female authors. By contrast, Italy, Spain, Japan and Austria offer optimal conditions for men in dermatological research. This finding correlates quite well with the results of the Global Gender Gap Report 2016 as the countries like Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark were ranked 2nd, 16th and 19th, respectively, whereas the countries like Spain, Italy, Austria and Japan were ranked 29th, 50th, 52nd and 111th, respectively, out of a total of 144 countries in the world.40 It is plausible to assume that these regional differences are not caused by discipline-specific characteristics, but rather, are primarily due to sociocultural surroundings, as, for example, Japan is characterised by a strong sense of patriarchy and traditional gender roles in society.41 This is all the more relevant, since similar constellations were found in most of our studies.12 14 Overall, the given information supplies women operating in the field of dermatology with a solid basis for decision-making for professional reorientation or career planning.

As in all our previous studies, we did not find a significant correlation between the FAP of a country and the distribution of prestigious authorships between the two genders.12 This means, countries with a high FAP can also provide disadvantageous career opportunities for women and vice versa. A valuable example is Italy with a high rate of FAP (54.2%) and a negative Prestige Index (−0.46). Interestingly, this finding is contrary to the sociocultural theory of the critical mass,42 postulating a self-sustained harmonisation of gender aspects once the participation of women has exceeded a critical threshold value of about 30%–35%.

Journals with a high degree of uniformity

At the level of individual journals, we reveal a striking uniformity of gender-specific authorship odds, as in 19 out of 23 journals women have significantly higher odds for first authorships and lower odds for last authorships. Evidently, the global gender-specific hierarchy of research groups is mapped to the related journals. This finding explains also the relatively small value range of the journals' Prestige Index compared with that of other countries (ΔPrestige Index: 0.69 vs 1.18). Remarkably, we do not find a significant correlation between the impact of a journal (characterised by the Scientific Journal Rankings (SJR)) and the revealed Prestige Index measuring the distribution of prestigious authorships between the two genders. Interestingly, this finding is contrary to our recent study analysing the FAP odds in 54 of highest-quality research journals listed in the Nature Index, which covers the journal categories Life Science, Multidisciplinary, Earth & Environmental and Chemistry. In this study, a clear negative correlation between the 5-year impact factor of a journal and its Prestige Index (r(52)=−0.63, P<0.01) was revealed.35 In contrast to academic dermatology, in this cross-discipline group of highest-impact journals, the female under-representation is accentuated in highly competitive articles attracting the highest citation rates, namely, articles with many authors and articles that were published in highest-impact journals (table 3). To conclude, uniformity of authorship odds as well as stable representation of women regardless of the journal impact speak for an advanced integration of women and against the predominance of ‘old boys' networks’ in the field of high-quality dermatology research and its related journals.14

Limitations of the study

Methodically, our purely bibliometric and algorithmic approach enables us to analyse large volumes of data standardised and independent of the examiner, and thus with a minimised interindividual variability. However, as already mentioned by Bendels et al,14 it is limited by the absence of information concerning equally distributed authorships, corresponding authors as well as data providing information about the scholar’s academic degree, their position (eg, Associate Professor vs Full Professor),1 age, employment status and their participation on editorial boards.26 43 Questionnaires or the inspection of, for example, online profiles provide a better access to this specific data, as shown by other studies.24 26 43 Furthermore, the investigation period is technically limited to articles that are published after 2006 due to the predominance of first names initials preventing a correct gender identification in older articles.20 Another limitation of the gender determination by first names is the fact that we had to exclude some countries from the country-specific analysis due to a relative high fraction of unisex names (primarily the Asian countries China and South Korea participating at 5% and 4%, respectively, of the articles).

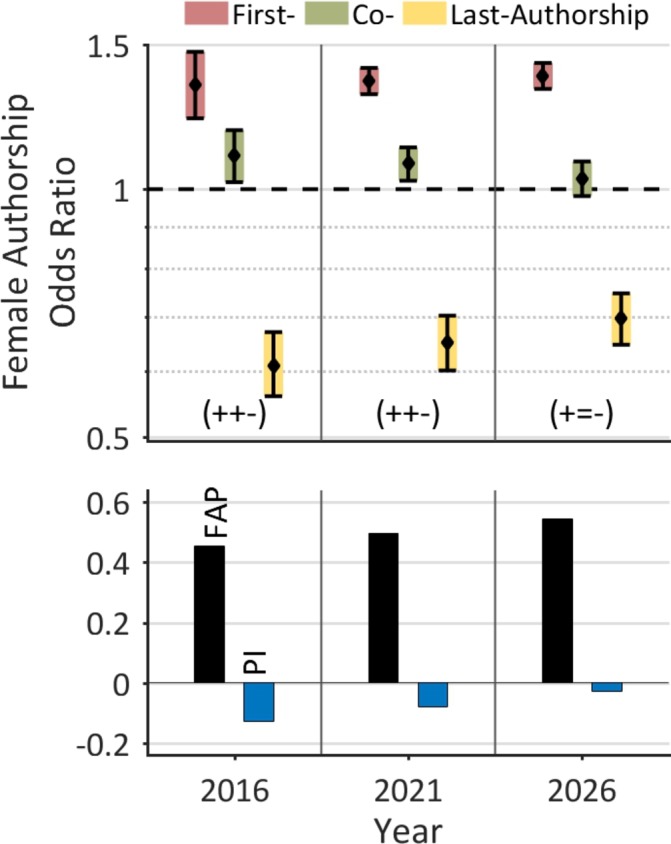

Conclusion and outlook

In conclusion, a) the relatively high FAP, b) the almost gender-neutral citation rates and c) the stable representation of female scholars in both articles with many authors as well as highest impact journals can be considered indicators for an advanced integration of women in high-quality dermatological research compared with other (medical) disciplines (table 3). However, a considerable career dichotomy is still present, with many female researchers at the beginning of their career and few women in academic leadership positions. Since there is a clear time-dependence present in authorship hierarchy—current early career researchers may be future research leaders—it is plausible to prognosticate a considerable increase of women in academic leadership positions in the next decade. This trend will likely be intense due to the high annual increase of FAP (1.74%) with the highest rates for the last author position (2.97%), and the trend of more and more female physicians entering the field of medicine in many Western countries.2 44 In line with this perspective, a linear prognosis of the temporal development of FAP prognosticates an FAP of 54.3% for the year 2026, and increasing female odds for last authorships and decreasing female odds for coauthorships (figure 4). This harmonisation in authorship odds results in a Prestige Index that is forecast to become almost gender-neutral in 2026 (Prestige Index=−0.03). On this basis, we expect a deeper integration of female scientists with a growing number of women in academic leadership positions in the next decade. However, it should be critically mentioned that, contrary to this prediction, various studies recently report about a striking persistence of gender inequalities regarding academic leadership positions despite a considerable increase in female first authorships.24–26 45

Figure 4.

Linear projection of the development of female authorships (FAP) on the global level. The prognosis for the next decades forecasts a further harmonisation of authorship odds between the two genders with an almost gender-neutral distribution of prestigious authorships in 2026 (Prestige Index (PI)=−0.03). An FAP of 54.3% is prognosticated for the year 2026.

In view of this, the present analysis may define a starting point: continuous monitoring over the next years will elucidate if female career dichotomy will break down, leading to a more balanced distribution of research leaders between both genders in dermatological research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

NS and DAG contributed equally.

Contributors: MHB, NS and DAG designed the study. MHB and MCD collected and performed the analysis. MHB, MCD, DB, GMO, NS and DAG interpreted the result. MHB wrote the first draft of manuscript. MHB, MCD, DB, GMO, NS and DAG contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Sadeghpour M, Bernstein I, Ko C, et al. Role of sex in academic dermatology: results from a national survey. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:809–14. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM, Raezer CL, et al. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2013-2014. 2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/ (accessed 11 Oct 2016).

- 3. Brooke B. Number of Female Medical School Enrollees Reaches 10-Year High. 2016. https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2016/ (accessed 1 Nov 2016).

- 4. Kimball AB. Sex, academics, and dermatology leadership: progress made, but no more excuses. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:844–6. 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pincus S. Women in academic dermatology. Results of survey from the professors of dermatology. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:1131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobson CC, Resneck JS, Kimball AB. Generational differences in practice patterns of dermatologists in the United States: implications for workforce planning. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1477–82. 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Resneck JS, Tierney EP, Kimball AB. Challenges facing academic dermatology: survey data on the faculty workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:211–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner E, Yoo J, Salter S, et al. Leadership workforce in academic dermatology. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:948–9. 10.1001/archderm.143.7.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobson CC, Nguyen JC, Kimball AB. Gender and parenting significantly affect work hours of recent dermatology program graduates. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:191–6. 10.1001/archderm.140.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shi CR, Olbricht S, Vleugels RA, et al. Sex and leadership in academic dermatology: A nationwide survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:782–4. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gollins CE, Shipman AR, Murrell DF. A study of the number of female editors-in-chief of dermatology journals. Int J Womens Dermatol 2017;3:185–8. 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bendels MHK, Bauer J, Schöffel N, et al. The gender gap in schizophrenia research. Schizophr Res 2018;193 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larivière V, Ni C, Gingras Y, et al. Bibliometrics: global gender disparities in science. Nature 2013;504:211–3. 10.1038/504211a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bendels MHK, Wanke E, Schöffel N, et al. Gender equality in academic research on epilepsy-a study on scientific authorships. Epilepsia 2017;58:1794–802. 10.1111/epi.13873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, et al. The "gender gap" in authorship of academic medical literature--a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006;355:281–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa053910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marušić A, Bošnjak L, Jerončić A. A systematic review of research on the meaning, ethics and practices of authorship across scholarly disciplines. PLoS One 2011;6:e23477 10.1371/journal.pone.0023477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murphy TF Authorship and Publication McGee G, Case Studies in Biomedical Research Ethics. 1. edn: The MIT Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tscharntke T, Hochberg ME, Rand TA, et al. Author sequence and credit for contributions in multiauthored publications. PLoS Biol 2007;5:e18 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fadeel B. "But many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first". Faseb J 2009;23:1283 10.1096/fj.09-0503LTR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bendels MH, Brüggmann D, Schöffel N, et al. Gendermetrics.NET: a novel software for analyzing the gender representation in scientific authoring. J Occup Med Toxicol 2016;11:43 10.1186/s12995-016-0133-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Filardo G, da Graca B, Sass DM, et al. Trends and comparison of female first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ 2016;352:i847 10.1136/bmj.i847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bendels MHK, Brüggmann D, Schöffel N, et al. Gendermetrics of cancer research: results from a global analysis on lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:101911–21. 10.18632/oncotarget.22089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. West M, Curtis J. AAUP faculty gender equity indicators. 2006. accessed 2006 https://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/63396944-44BE-4ABA-9815-5792D93856F1/0/AAUPGenderEquityIndicators2006.pdf

- 24. Long MT, Leszczynski A, Thompson KD, et al. Female authorship in major academic gastroenterology journals: a look over 20 years. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:e1443:1440–7. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang T, Zhang C, Khara RM, et al. Assessing the Gap in Female Authorship in Radiology: Trends Over the Past Two Decades. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:735–41. 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Amering M, Schrank B, Sibitz I. The gender gap in high-impact psychiatry journals. Acad Med 2011;86:946–52. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182222887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bickel J, Ruffin A. Gender-associated differences in matriculating and graduating medical students. Acad Med 1995;70:552–9. 10.1097/00001888-199506000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramsden P. Describing and explaining research productivity. Higher Education 1994;28:207–26. 10.1007/BF01383729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cikara M, Rudman L, Fiske S. Dearth by a Thousand Cuts? Accounting for Gender Differences in Top-Ranked Publication Rates in Social Psychology. J Soc Issues 2012;68:263–85. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01748.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van den Besselaar P, Sandström U. Gender differences in research performance and its impact on careers: a longitudinal case study. Scientometrics 2016;106:143–62. 10.1007/s11192-015-1775-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West JD, Jacquet J, King MM, et al. The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS One 2013;8:e66212 10.1371/journal.pone.0066212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Figg WD, Dunn L, Liewehr DJ, et al. Scientific collaboration results in higher citation rates of published articles. Pharmacotherapy 2006;26:759–67. 10.1592/phco.26.6.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schisterman EF, Swanson CW, Lu YL, et al. The Changing Face of Epidemiology: Gender Disparities in Citations? Epidemiology 2017;28:159–68. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Symonds MR, Gemmell NJ, Braisher TL, et al. Gender differences in publication output: towards an unbiased metric of research performance. PLoS One 2006;1:e127 10.1371/journal.pone.0000127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bendels MHK, Müller R, Brueggmann D, et al. Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by Nature Index journals. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189136 10.1371/journal.pone.0189136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garfield E. The evolution of the Science Citation Index. Int Microbiol 2007;10:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, et al. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med 2011;86:43–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff9ff2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brooks J, Della Sala S. Re-addressing gender bias in Cortex publications. Cortex 2009;45:1126–37. 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neuroscience N. Women in neuroscience: a numbers game. Nat Neurosci 2006;9:853 10.1038/nn0706-853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leopold TA. The Global Gender Gap Report 2016: World Economic Forum, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iwao S. The Japanese woman: traditional image and changing reality / Sumiko Iwao. New York: Toronto: New York: Free Press; Maxwell Macmillan Canada; Maxwell Macmillan International, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Childs S, Mona LK. Critical Mass Theory and Women’s Political Representation. Political Studies 2008;56:725–36. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mueller CM, Gaudilliere DK, Kin C, et al. Gender disparities in scholarly productivity of US academic surgeons. J Surg Res 2016;203:28–33. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.03.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Council GM. The state of medical education and practice in the UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaufman RR, Chevan J. The gender gap in peer-reviewed publications by physical therapy faculty members: a productivity puzzle. Phys Ther 2011;91:122–31. 10.2522/ptj.20100106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Introducing the Index. Nature 2014;515:S52–3. 10.1038/515S52a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020089supp001.pdf (953.8KB, pdf)