Abstract

Objective

To examine the value of percent body fat (%BF) with body mass index (BMI) to assess the risk of abnormal blood glucose (ABG) among US adults who are normal weight or overweight. We hypothesised that normal-weight population with higher %BF is more likely to have ABG.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2006, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Participants

Participants were US adults aged 40 and older who have never been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes by a doctor (unweighted n=6335, weighted n=65 705 694). The study population was classified into four groups: (1) normal weight with normal %BF, (2) normal weight with high %BF, (3) overweight with normal %BF and (4) overweight with high %BF.

Main outcome measures

ORs for ABG including pre-diabetes and undiagnosed diabetes (HbA1c ≥5.7%, ≥39 mmol/mol).

Results

64% of population with normal BMI classification had a high %BF. Prevalence of ABG in normal-weight group with high %BF (13.5%) is significantly higher than the overweight group with low %BF (10.5%, P<0.001). In an unadjusted model, the OR of ABG was significantly greater in adults at normal BMI with high %BF compared with individuals at normal weight with low %BF. In an adjusted model controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, first-degree-relative diabetes, vigorous-intensity activities and muscle strengthening activities, risks of ABG were greater in population with normal weight and high %BF (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.38) and with overweight and low %BF (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.98, P<0.05).

Conclusions

Integrating BMI with %BF can improve in classification to direct screening and prevention efforts to a group currently considered healthy and avoid penalties and stigmatisation of other groups that are classified as high risk of ABG.

Keywords: abnormal glucose, diabetes prevention, percent body fat, body mass index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study used population-based nationally representative data allowing for generalisability.

We used the most accurate body composition measurement, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), to assess direct impact of high body fat on abnormal blood glucose.

Percent body fat integrating with body mass index improved classification of population who has high body fat associated with high risk of abnormal blood glucose.

The data are relatively old while these are the most recent data including whole-body DXA measurement.

There is no gold standard cut-off points in defining obesity according to percent body fat.

Introduction

Diabetes has become a worldwide epidemic. It is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the USA, and its prevalence has been steadily increasing.1 2 The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes reached 12.3% of US adults in 2011–2012.1 Furthermore, the total direct medical costs for diabetes was US$176 billion in 2012 and healthcare expenditure for people with diabetes is two times higher than people without diabetes.3

In an effort to prevent diabetes and identify patients with undiagnosed diabetes for potential treatment, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening of abnormal blood glucose (pre-diabetes or undiagnosed diabetes) for asymptomatic adults.4 5 The USPSTF recommends screening adults aged between 40 years old and 70 years old only if they are overweight or obese defined by body mass index (BMI) cut-offs.4 Recently, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) proposed the rule that if employees who are overweight or obese fail to achieve a normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) through wellness programmes, they penalise the employees who participate in wellness programmes up to 30% of the total costs of health insurance.6 Consequently, BMI levels have substantial implications for defining someone as low risk of abnormal blood glucose (ABG) or high risk of ABG.

BMI, which is widely adopted to assess obesity-related risk in clinical setting, however, may misclassify some segments of the general population who are at metabolic risk. While BMI is a simple equation based on height and weight, body weight includes body fat, muscle, bone and body water.7 Recent studies found that half of people who were obese according to percent body fat (%BF) but were classified as normal weight defined by BMI, and about 18% of adults with high %BF who were classified as not being obese, showed a significant higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome.8 9 Recent data indicate that a significant proportion of people with a normal weight designated by BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) have pre-diabetes, undiagnosed diabetes and hypertension.10–12 In fact, 33% of adults 45 years old and older at a normal weight have pre-diabetes. Moreover, a normal weight obesity, which represents individuals who fall into normal range of BMI and who have high body fat mass, is associated with higher risk of metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality.13 14 On the other hand, professional football players who are typically classified as being obese due to high muscle mass actually showed better cardiovascular health compared with the general population.15

Because of the possible deleterious consequences due to BMI misclassification, %BF may have some value as an addition to BMI to improve classification of individuals as low risk of ABG or high risk of ABG.16–18 However, the extent to which adding %BF to BMI improves classification of risk is unclear. There has been little investigation to determine the incremental value of combining BMI and %BF in a risk assessment for ABG. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine in a nationally representative sample the value of %BF with BMI to assess the risk of abnormal glucose among adults who are normal weight or overweight and improve classification.

Methods

We analysed the nationally representative, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for the years of 1999–2006. Although there are more recent NHANES data, these are the most recent data with a whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) that measures %BF. The NHANES is a national representative survey of non-institutionalised US population using a complex stratified multistage probability cluster sample design. To account for nationally representative population estimates, the National Center for Health Statistics applies a multilevel weighting system. The survey included a standardised medical examination including blood and urine analysis for examining biomarkers and a number of health-related interviews. The current study was approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida.

Anthropometric assessment

BMI was obtained from body weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Weight and height were measured by a trained examiner in the mobile examination centre, and these were used to calculate BMI.19 BMI values were categorised into four groups (ie, underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity) on the basis of guideline of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE).7 %BF was derived from one to three times weekly measured whole-body DXA scan (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA).20 A sex-specific threshold of %BF was adopted as 25% for men and 35% for women given by the AACE/ACE guideline (obesity in men ≥25% and women ≥35%).7

Participants

The current study focused on adults aged over 40 years old or older who have never been told by a doctor or a health professional that they have diabetes (unweighted n=6335). We focused on individuals 40 years old and older since 40 years old is the lower age cut-off for screening for ABG as suggested by the USPSTF.4 The study population was individuals with normal weight or overweight as defined by BMI. We limited the study to these individuals because they were the groups most likely to potentially be classified by the addition of %BF to BMI.

Participants were limited to normal-weight and overweight population (18.5–29.9 kg/m2) and classified as four groups based on combined BMI and %BF. Respondents who were underweight and obese defined by BMI were excluded (missing n=5744). In normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), the first group who had normal BMI and low %BF would be assessed to be at low risk. The second group may be classified as low risk of ABG even though existing data suggest a substantial population have pre-diabetes (normal BMI but high %BF).12 Among individuals classified as overweight by BMI (25–29.9 kg/m2), the third group may be classified as high risk of ABG, but they may be healthy due to the BMI limitation of not appropriately assessing extensive muscle mass (overweight and low %BF). The fourth group would be at high risk based on having high fat (overweight and high %BF). Pregnant women who were not allowed to test the DXA examination were excluded. Also, we excluded the obese population because of the known high risk.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is an abnormal glucose including pre-diabetes or undiagnosed diabetes, an HbA1c level of 5.7% or higher (≥39 mmol/mol). All subjects reported never having been told by a doctor or a health professional that they had pre-diabetes or diabetes.5 We excluded individuals with an HbA1c of 4.0% (≤20 mmol/mol) that is associated with increased mortality without diabetes.21

Covariates

Age was classified into two groups with cut-offs of 40 years old and 71 years old. Race/ethnicity was categorised into four groups: (1) Non-Hispanic White, (2) Non-Hispanic Black, (3) Hispanics and (4) Other. Family history is a predictor of diabetes according to preliminary study.22 Thus, we selected family history of diabetes representing a first degree of relative ever being told by a health professional that they had diabetes.

We also assessed physical activity. Vigorous intensity activity helps to increase muscle mass and reduce body fat and it may result in overweight despite low %BF. Also, physical activity represents a lifestyle intervention to control blood glucose. Vigorous activity was defined as reports of an activity that causes a slight to moderate increase in breathing or heart rate for at least 10 min over the past 30 days. Muscle strengthening activity refers to any physical activities designed to strengthen muscles including lifting weights, push-ups or sit-ups over the past 30 days.

Statistical analysis

To account for the stratified multistage probability sample design, we used SAS V.9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and SUDAAN software (RTI, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA) for data analyses. Weighting and design variables applied to all analyses from univariate analyses, χ2 tests and logistic regression models. They allow us to calculate population estimates for non-institutionalised US population. We examined the bivariate relationship between combined BMI/%BF and abnormal glucose. Following by, both unadjusted and adjusted logistic regressions controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family history of diabetes, vigorous activity and muscle strengthening activity were employed to assess the likelihood of having ABG.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in this study.

Results

The total unweighted sample size was 6335 US adults representing 65 705 694 adults in the US population. No variable had more than 3% unweighted missing data and none of the demographics had any missing data. It is important to note that the population estimates are based on weighted sample. Table 1 shows that among normal-weight population, approximately 64% of population of normal BMI classification had a high %BF. Prevalence of abnormal glucose by combined BMI and %BF is shown in table 2. Prevalence of abnormal blood glucose in the normal weight group with high %BF (13.5%) is significantly higher than the overweight group with low %BF (10.5%) (P<0.001). About 78% of the study population was adults aged between 40 years old and 70 years old and non-Hispanic white. In sex, most men showed low %BF whereas more than 70% of women have a high level of body fat within normal-weight population. Regardless of BMI, more than 40% of the study population with low %BF performed vigorous-intensity activity as well as muscle strengthening activity compared with population with high %BF (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Body mass index (BMI) classification among US adults aged over 40 or older who are normal weight and overweight stratified by BMI and percent body fat (%BF) (unweighted n=6335 and weighted n=65 705 694)

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | |

| %BF | ||

| Low | 36.3 | 9.0 |

| High | 63.7 | 91.0 |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of adults aged over 40 or older who are normal weight and overweight (unweighted n=6335 and weighted n=65 705 694)

| Body mass index | Normal | Overweight | P values | ||

| % Body fat | Low | High | Low | High | |

| Unweighted sample size | 908 | 1679 | 327 | 3421 | |

| Weighted sample size | 10 259 138 | 18 020 486 | 3 382 474 | 34 043 596 | |

| Prevalence of abnormal blood glucose | 8.6 | 13.5 | 10.5 | 20.0 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| 40 to 70 | 92.3 | 81.1 | 96.0 | 85.2 | <0.001 |

| 71 or older | 7.7 | 18.9 | 4.0 | 14.8 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 61.1 | 28.8 | 96.2 | 53.4 | <0.001 |

| Female | 38.9 | 71.2 | 3.8 | 46.6 | |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 77.5 | 80.4 | 70.4 | 77.0 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.7 | 4.8 | 17.0 | 8.0 | |

| Hispanics | 6.5 | 7.1 | 10.0 | 10.9 | |

| Others | 4.3 | 7.7 | 2.6 | 4.2 | |

| First-degree-relative diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 35.9 | 45.5 | 43.6 | 46.9 | <0.001 |

| No | 64.2 | 54.5 | 56.4 | 53.1 | |

| Vigorous activity | |||||

| Yes | 41.7 | 28.1 | 45.9 | 30.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 58.3 | 71.9 | 54.1 | 69.6 | |

| Muscle-strengthening activities | |||||

| Yes | 40.5 | 25.1 | 38.1 | 23.4 | <0.001 |

| No | 59.5 | 74.9 | 61.9 | 76.7 | |

In an unadjusted logistic regression, the OR of abnormal glucose was significantly greater in adults at normal weight with high %BF compared with individuals at normal weight with low %BF as the reference group (table 3). Conversely, ABG risk was not significantly more likely in overweight adults with low %BF when compared with the normal-weight/low %BF group. In an adjusted model controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, first-degree-relative diabetes, vigorous-intensity activities and muscle strengthening activities, the adjusted model results were similar to the unadjusted results. Risks of ABG were greater in population with normal weight and high %BF as well as the overweight with high %BF (table 3).

Table 3.

OR (95% CI) for the abnormal glucose for adults with normal weight and overweight in unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, first-degree-relative diabetes, vigorous activities and muscle-strengthening activity

| BMI | %BF | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | Low | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High | 1.66 (1.13 to 2.43)* | 1.55 (1.01 to 2.38)* | |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | Low | 1.25 (0.75 to 2.07) | 1.17 (0.69 to 1.98) |

| High | 2.64 (1.86 to 3.76)* | 2.45 (1.61 to 3.71)* |

*Statistically significant at 0.05.

BMI, body mass index; %BF, percent body fat.

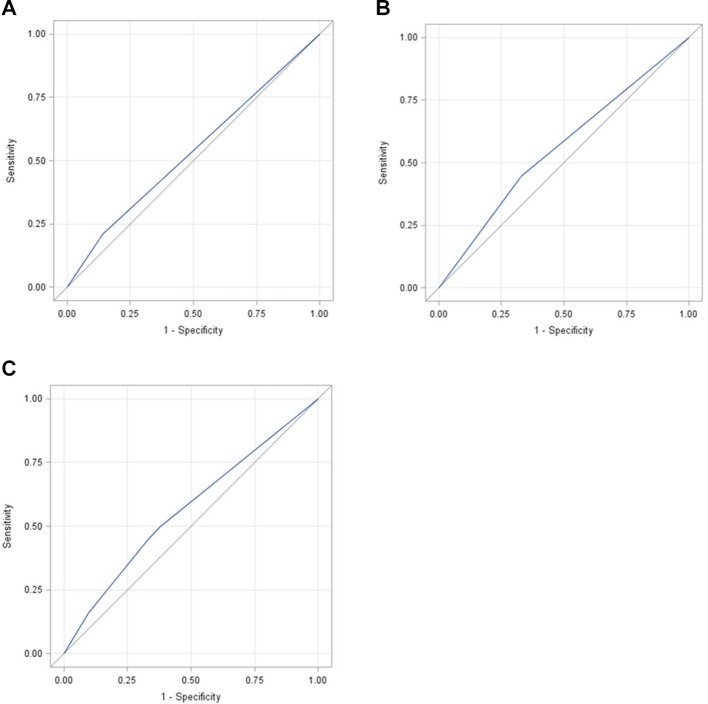

In sensitivity analyses, area under the curve of combined form of BMI and %BF was larger than areas of BMI only or %BF only (figure 1). These areas were significantly different (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Comparisons of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves among body mass index (BMI) only, percent body fat (%BF) only and combined form of BMI and %BF. (A) ROC curve for %BF only (area under the curve (AUC)=0.5342). (B) ROC curve for BMI only (AUC=0.5571). (C) ROC curve for combined form of %BF and BMI (AUC=0.5663).

Discussion

The use of BMI only may misclassify segments of the adult population in terms of risk of abnormal glucose. Our key findings showed that individuals with normal weight who have high %BF have significantly higher risk of abnormal glucose compared with individuals with normal weight and low %BF. Conversely, of individuals with overweight, low %BF is not significantly associated with the risk of abnormal glucose. The results suggest that %BF combined with BMI may help to improve risk stratification for ABG in these intermediate groups.

Since body weight comprises fat and also a variety of body compositions such as muscle, organs and body water, it may not estimate the actual amount of body fat. Professional football players who are typically classified as obese due to high muscle mass showed better cardiovascular health compared with the general population.15 In addition, among military population, whereas an average of BMI was overweight, almost half of them had never had any form of sickness absence.23 Furthermore, since according to our preliminary study 33% of normal-weight population has pre-diabetes, %BF may identify this normal-weight population at risk of development of ABG.11 These evidences indicate that %BF may be a key factor in improving to estimate risk of chronic disease.

Our key findings may suggest refinement of current clinical guidelines with additional body composition assessments. The USPSTF and the American Diabetes Association have BMI as a key component of recommendations for diabetes prevention.4 5 There may be missed opportunities for screening, particularly for pre-diabetes. Regardless of BMI, people with high %BF were older, female and non-Hispanic white. While the proportion of family history patients positive for diabetes was similar across four groups, physical activity was different among groups. It is particularly important, as shown in our findings, that we appropriately classify the overweight population with low %BF. This population has been neglected as being classified as a healthy population. Our finding showed that these individuals are significantly more likely to perform high-intensity physical activities compared with the normal-weight population who had low %BF, and this behaviour may result in overweight. For instance, professional athletes or civil forces with higher muscle mass who are typically classified as obese measured by BMI may fail to meet normal BMI criteria in recruitment screening.24 In addition, according to the rule offered by EEOC, employees who are classified as overweight or obese with high muscle mass and lower body fat may get penalised.6 Our findings indicated that BMI may not be the optimal tool to assess health outcomes for employees and the new rule of the EEOC should be modified to consider body fat instead of body weight. Using a concept of normal weight obesity is also an opportunity to better detect population at risk of ABG to receive appropriate prevention services. This strategy may detect more than 303 000 US adults who are normal weight and who usually miss an opportunity to receive preventive care service on time due to the use of BMI only. To prevent these adverse events, more accurate body composition assessments may be required.

A direction for future research might be to refine the cut points for %BF, particularly in a longitudinal cohort. Further, it may be important to consider some other variables that may confound the relationship between %BF and diabetes like poverty, diet quality, smoking and sleep.25 26 In particular, these variables may be important for future interventions.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, there is no gold standard clinical cut point to indicate high or low percentage body fat. While numerous studies used a variety of sex-specific thresholds, sensitivity analysis has not been implemented yet. The current study, however, adopted commonly used criteria as a way to promote generalisability and comparability with other studies. Second, although this is a study investigating the association between several physiological measures, the data are not the most recent NHANES data and so population estimates may not totally represent the current US population. While there are more recent NHANES data, the data used in the study are the most recent data with a whole-body DXA measurement. We felt that the validity of the DXA scan for %BF was a strength that outweighed the recent data collection. Third, our analyses were cross-sectional and did not allow us to look at the downstream risks of individuals with normal weight obesity. However, our primary goal was to improve on BMI in the accuracy of screening guidelines for individuals with current AB, which thereby requires cross-sectional analyses. Lastly, the use of a DXA scan may be an economic burden in healthcare setting. While a DXA scan is the most accurate technique to measure body compositions, it is prohibitively expensive to use for the purpose of screening only. Current insurance companies do not cover the use of DXA scan for the purpose of screening of chronic diseases. Bioelectrical impedance analysis, which assesses %BF, may be a cost-effective alternative for the purpose of ABG screening in primary care setting, while the current study used the data measured by DXA scan.

Conclusion

BMI, which is typically used to define normal weight or overweight in a clinical setting, may misclassify populations in relation to ABG. Integrating BMI with %BF can help in classification to direct screening and prevention efforts to a group currently considered low risk of ABG and avoid penalties and stigmatisation of other groups that are classified as high risk of ABG.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AJ led the entire research as the first author from writing the manuscript, analysing the data and interpretation. AGM supervised the entire process of the research as a research mentor and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey access (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

References

- 1. Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, et al. . Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015;314:1021–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL, et al. . Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. JAMA 2015;314:1731–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1033 10.2337/dc12-2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. U.S. Final Recommendation Statement: Healthful Diet and Physical Activity: Counseling Adults with High Risk for CVD. Rockville, MD: US Preventive Services Task Force, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. EEOC. Questions and answers about EEOC’s notice of proposed rulemaking on employer wellness programs. Washington, DC: US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dickey RA, Bartuska DG, Bray GW, et al. . AACE/ACE Position statement on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of obesity (1998 revision). Endocr Pract 1998;4:297–350. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okorodudu DO, Jumean MF, Montori VM, et al. . Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2010;34:791–9. 10.1038/ijo.2010.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peterson MD, Al Snih S, Stoddard J, et al. . Obesity misclassification and the metabolic syndrome in adults with functional mobility impairments: Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. Prev Med 2014;60:71–6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Anton SD, et al. . Grip strength as a marker of hypertension and diabetes in healthy weight adults. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:850–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Anton SD, et al. . Physical activity and abnormal blood glucose among healthy weight adults. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:42–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Jo A, et al. . Prevalence of prediabetes and abdominal obesity among healthy-weight adults: 18-year trend. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:304–10. 10.1370/afm.1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marques-Vidal P, Pécoud A, Hayoz D, et al. . Prevalence of normal weight obesity in Switzerland: effect of various definitions. Eur J Nutr 2008;47:251–7. 10.1007/s00394-008-0719-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliveros E, Somers VK, Sochor O, et al. . The concept of normal weight obesity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014;56:426–33. 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tucker AM, Vogel RA, Lincoln AE, et al. . Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among National Football League players. JAMA 2009;301:2111–9. 10.1001/jama.2009.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. . Normal weight obesity: a risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. Eur Heart J 2010;31:ehp487 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shea JL, King MT, Yi Y, et al. . Body fat percentage is associated with cardiometabolic dysregulation in BMI-defined normal weight subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012;22:741–7. 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, et al. . Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:694–701. 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. CDC. NHANES: anthropometric procedures manual. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. NHANES. Documentation, codebook, and frequencies: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Atlanta, GA: NHANES, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carson AP, Fox CS, McGuire DK, et al. . Low hemoglobin A1c and risk of all-cause mortality among US adults without diabetes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:661–7. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Eckardstein A, Schulte H, Assmann G. Risk for diabetes mellitus in middle-aged Caucasian male participants of the PROCAM study: implications for the definition of impaired fasting glucose by the American Diabetes Association. Prospective Cardiovascular Münster. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3101–8. 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kyröläinen H, Häkkinen K, Kautiainen H, et al. . Physical fitness, BMI and sickness absence in male military personnel. Occup Med 2008;58:251–6. 10.1093/occmed/kqn010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Beyond body mass index. Obes Rev 2001;2:141–7. 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, et al. . Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:414–20. 10.2337/dc09-1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, et al. . Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep 2008;31:619–26. 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.