Abstract

Objectives

To clarify competencies for inclusion in our curriculum that focuses on developing leaders in community medicine.

Design

Qualitative interview study.

Setting

All six regions of Japan, including urban and rural areas.

Participants

Nineteen doctors (male: 18, female: 1) who play an important leadership role in their communities participated in semistructured interviews (mean age 48.3 years, range 34–59; mean years of clinical experience 23.1 years, range 9–31).

Method

Semistructured interviews were held and transcripts were independently analysed and coded by the first two authors. The third and fourth authors discussed and agreed or disagreed with the results to give a consensus agreement. Doctors were recruited by maximum variation sampling until thematic saturation was achieved.

Results

Six themes emerged: (1)‘Medical ability’: includes psychological issues and difficult cases in addition to basic medical problems. High medical ability gives confidence to other medical professionals. (2)‘Long term perspective’: the ability to develop a long-term, comprehensive vision and to continuously work to achieve the vision. Cultivation of future generations of doctors is included. (3) ‘Team building’:the ability to drive forward programmes that include residents and local government workers, to elucidate a vision, to communicate and to accept other medical professionals. (4)‘Ability to negotiate’: the ability to negotiate with others to ensure that programmes and visions progress smoothly (5) ‘Management ability’: the ability to run a clinic, medical unit or medical association. (6) ‘Enjoying oneself’: doctors need to feel an attraction to community medicine, that it be fun and challenging for them.

Conclusions

We found six competencies that are needed by leaders in the field of community medicine. The results of this study will contribute to designing a curriculum that develops such leaders.

Keywords: community medicine, leader, competency, qualitative study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study qualitatively explores competencies through the perceptions of real leaders of community medicine.

Individual interviews contribute to capturing the perceptions of the individual regarding the competencies needed by a leader in the field of community medicine.

Limitations include that the interviewer belongs to the general medicine department. Thus, there is potential bias in his perception of community medicine.

Introduction

The Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care in 1978 suggested that the concept of primary healthcare was the key strategy to achieving good health for all1; thus, the development of primary healthcare plays an important role in health promotion around the world. In addition, the 34th WHO Assembly in 1981 suggested the adaptation of a global strategy for reorientation of national health systems based on primary healthcare.2 Community health centres are facing a shortage of primary care physicians at a time when government plans have called for an expansion of community health centre programmes. To succeed with this expansion, community health centres require additional well-trained physician leadership.3 Furthermore, it acknowledged the need for appropriate training of healthcare professional so that they are prepared for the tasks they will have to perform. Influenced by this trend, education in community medicine, which we define as a branch of medicine that is concerned with the health of the members of a community, municipality or region has become popular throughout the world4 and is now incorporated in the model core curriculum in Japan.5 In addition, because the collapse of community medicine has been a serious problem in Japan, training in community medicine is currently emphasised in medical undergraduate education.6

It is also problematic that little research has been done in Japan into the competencies necessary for leaders in community medicine.

The purpose of training in community medicine is to communicate the current status of community medicine and to develop the abilities necessary to a successful career in this field, which we hope will help motivate medical students to make a substantial contribution to community medicine. It is accepted that leadership is a critical factor in organisations as it has a great effect on goals, visions, strategy, social environment and work motivation among employees.7 High-quality healthcare increasingly relies on teams, collaboration and interdisciplinary work, making physician leadership essential for optimising health system performance.8–10 In general, Schwartz and Pogge reported that (1) strategic and tactical planning, (2) persuasive communication, (3) negotiation, (4) financial decision-making, (5) team building, (6) conflict resolution and(7) interviewing are essential skills in physician leadership.11 Another paper on leadership by Kouzeu and Posner reported the following attributes: (1) challenge the process, (2) inspire a shared vision, (3) enable others to act, (4) model the way and (5) encourage the heart.12 Further, it is reported that the key elements of clinical leadership at an academic medical centre fall into four important themes: (1) management of the team, (2) establishing a vision, (3) communication and (4) personal attributes.13 The ‘five-star doctor’ concept was proposed by the WHO as an ideal profile of a doctor possessing a mix of aptitudes necessary to carrying out the range of services that a health setting must deliver to meet the requirement of relevance, quality, cost-effectiveness and equity in health.14 A ‘five-star doctor’ can be summarised as a care provider, decision-maker, communicator, community leader and manager. In this paper, a community leader is defined as a doctor who meets the needs and problems of the whole community in a suburban or rural setting. According to the WHO, understanding the determinants of health inherent in the physical and social environment and by appreciating the breadth of each problem or health risk, ‘five-star doctors’ do not simply treat individuals who seek help but will also take a positive interest in community health activities, which will benefit a large number of people. However, the competencies that are required of community leaders are vague in this WHO definition. Moreover, there have as yet been no competencies established in Japan for educational curriculums to develop such leaders. Competency-based medical education (CBME) has become a core strategy in the USA and internationally as a means to educate and assess the next generation of physicians. Models of CBME are driven by the expansion of scientific knowledge and changes in medical practice.15–17 Competency-based frameworks offer structural, contentment and process based benefits.

At present, training in community medicine is being done in all medical universities, medical students do clinical clerkships, and they study the importance of interprofessional relations, which creates a mindset for community medicine.

In the future, to contribute to the development of community medicine, it will be necessary for medical students to start to gain a comprehensive ability to solve a wide variety of problems, including in family and community settings in both rural and urban area, and the ability to be a leader in groups of people of various professional orientations, including hospital and clinic cooperation. To gain such ability, students must have clinical skill and the motivation to become a leader in the community setting. Curricula to teach leadership in the clinical setting are being provided all over the world.18–21 However, it has been reported that the abilities needed by leaders in a focused community setting are different from those in the general clinical setting.22 There have as yet been no competencies established for educational curriculums to develop such leaders. This exploratory study was done to clarify the competencies important to such an educational curriculum.

Materials and methods

Design

The study design was descriptive qualitative research using in-depth interviews.

Setting

All six regions of Japan, including urban and rural areas.

Sampling

Maximum variation sampling was conducted. The administrative director and vice president of the Japan Primary Care Association (JPCA) were asked in 2014 to recommend candidates who are active as leaders of community medicine. Three academic organisations, the Japanese Medical Society of Primary Care, the Japanese Academy of Family Medicine and the Japanese Society of General Medicine merged into JPCA on 1 April 2010. The organisation’s aims include the promotion of accessible, continuing, comprehensive healthcare and related scientific activities that help citizens lead a healthy life. The administrative director and vice president of the JPCA recommended 25 candidates. The research coordinator and the coauthors of this paper discussed the interview guide and appropriateness of the recommended doctors, with a balance of doctors from rural and urban areas. E-mails in which the objectives of the study were described were sent to the candidates. Fortunately, all of the candidates agreed to be interviewed. The study protocol was approved by the Kyushu University Hospital Ethics Committee (26-217). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Interview

The first author conducted all of the semistructured interviews using the interview guide shown in box 1. He belonged to the Department of General Medicine of Kyushu University Hospital for 5 years and now manages the clinical training centre for community medicine in the undergraduate school. He is a specialist of herbal medicine (Kampo) and community medicine. He had not met the participants previous to the interview. He was trained by the second author, who is an expert in qualitative research. All doctors gave consent to publish the results of their interview. The face-to-face interviews took place at the physician’s place of practice between November 2014 and July 2015. Each interview lasted for 1 to 2 hours. There was no one else present besides the participant and the interviewer. The questions included in the interview guide did not change over time and served as a checklist of points for discussion. However, interviews were flexible and allowed the participants to take the discussion in any direction they wished.

Box 1. Interview guide.

What competencies do you feel are necessary to becoming a leader in community medicine?

Why do you think they are necessary?

Please tell me an episode that illustrates why the competency is necessary?

How did you learn this competency?

Please tell me how you think a person can acquire it?

What advice can you give us for developing an educational programme for training future leaders in the field of community medicine?

I will summarise what I heard. Is my understanding correct?

Data analysis

The semistructured interviews of the selected participants were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim and double checked by our well-trained technicians. The transcriptions were saved as a Microsoft Word document, deidentified and then read. Transcripts were independently analysed and coded by the four authors to extract the competencies proposed by the interviewees. In the first stage, data were analysed openly. However, each author used the constant comparative method, which involves constant and repeated checking of the interpretation of the data.23 After data collection and individual analysis, the authors discussed the data to build a consensus. The first and second authors checked the interpretation of the themes derived from the data to confirm that the data were interpreted deductively. The third and fourth authors discussed and agreed or disagreed with the results to give a consensus agreement.

Data collection

Twenty doctors (male: 19, female: 1) participated in the semistructured interviews. The analysis reached saturation after the interviews of all participants and no new theme had emerged. The data of one doctor were eliminated from the analysis because his answers were vague and could not be summarised. Mean age of the interviewees was 48.3 years (range 34–59), and the mean years of clinical experience was 23.1 years (range 9–31). The areas in which the doctors interviewed practice are as follows: Hokkaido-Tohoku four, Kanto four, Hokuriku three, Kansai two, Chugoku-shikoku four and Kyushu-Okinawa two. Quotations were selected that illustrate the themes and convey these physicians’ experiences.

Results

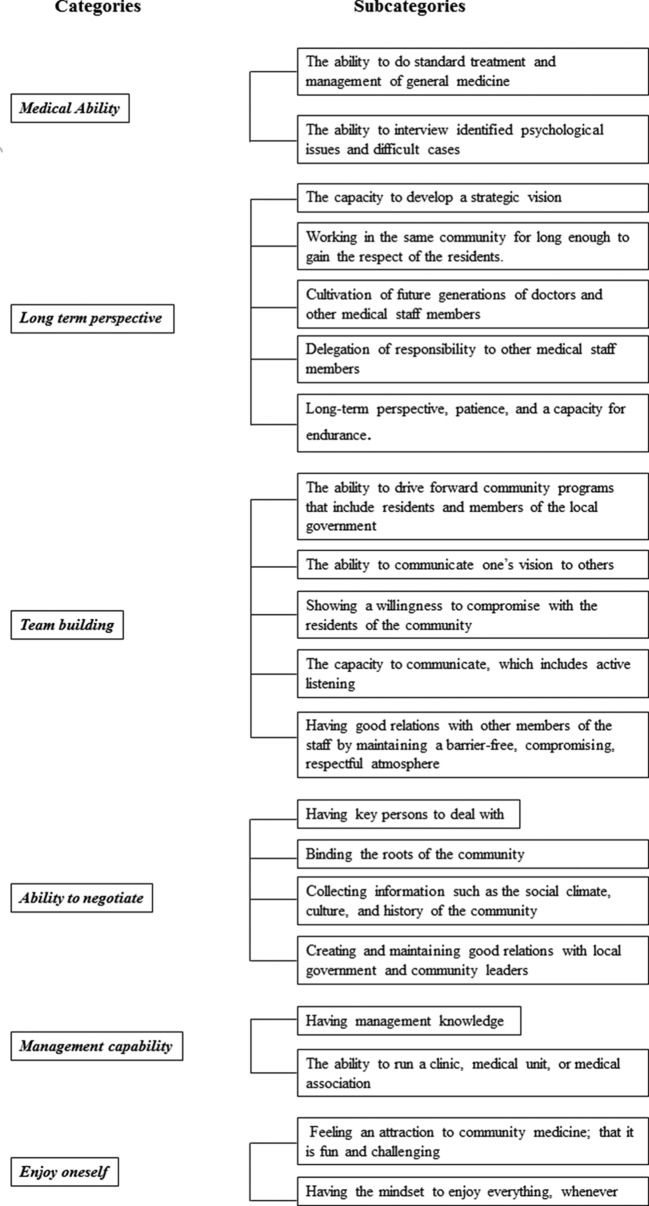

Six themes emerged from analysis of the responses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Twenty competency subcategories divided into six themes.

Medical ability

In addition to routine general medicine, the doctors interviewed identified psychological issues and difficult cases as being important to community medicine. They also felt it is important that confidence be developed through interaction with other medical professionals. Of note, the doctors thought that all Japanese doctors can do standard treatment and management, and thus specialised medical ability is not necessary.

If I do not have clinical ability and the ability to solve problems, no one will trust me. (P4)

In dealing with difficult problems that I cannot solve by myself, involving other members of the community through continuing contact will lead to solving the problem. (P11)

Long-term perspective

‘Long-term perspective’ refers to developing a comprehensive, long-term vision, then practising continuously to achieve the vision. The leader needs the capacity to develop a strategic vision to improve the health of the community over the long term and to be able to see the ‘big picture’ to keep sight of the direction in which community medicine is moving. It is also important to work in the same community for long enough to gain the respect of the residents. Cultivation of future generations of doctors and other medical staff members is an important aspect of this vision. Cultivating medical staff members includes delegation of responsibility to other medical staff members to reduce the workload of the leader. Further, cultivating future generations of doctors and other medical staff members requires patience and persistence needs. A sense of balance and flexibility in meeting situations encountered were also included in the theme. To solve the problems of the community and to cultivate productive members require a long-term perspective, patience and a capacity for endurance.

I think they should have a sense of the needs of the community and think strategically about many things. (P3)

I think that it will be difficult to become a leader in the field of community medicine if you can not observe things comprehensively. (P4)

I think it is necessary to have a view of at least five to six years. (P7)

I think that the task that is most important and most difficult for leaders is to cultivate and keep a successor. (P13)

Team building

‘Team building’ means the ability to drive forward community programmes that include residents and members of the local government to communicate and bring about a vision and to gain the acceptance of other medical professionals. Moreover, the leader needs to show a willingness to compromise with the residents of his community, have good relations with other members of the staff by maintaining a barrier-free, compromising, respectful atmosphere that takes into account the viewpoints of each other. For this process to be successful, the leader must have a vision, the ability to communicate the vision to others, must not whimsically change the vision and must take on the role of conduit so that community members will be able to communicate the vision of the leader to their staff. Further, the capacity to communicate, which includes active listening, effective word usage and the capacity to make decisions fitting to the times are also important. It is important to remember that private opinions should not be communicated to other members.

The ability to understand resources and the occupational ability of other medical professionals and to organise professionals is important. (P8)

To become a person who is easy to consult. This means to be easy to talk to. (P1)

There are things that I must go ahead with even if they are opposed by other members. I think that the strength to show your vision is necessary. (P15)

If a doctor does not go out into the community in a positive manner, many things will not go well. (P2)

Ability to negotiate

The ability to negotiate with others to ensure that programmes and visions progress smoothly. In the objectives, local government was also included. A leader must create and maintain good relations with local government and community leaders, and it is important to have key persons to deal with. A leader makes the first step to go to the community to collect information such as the social climate, culture and history of the community so that he can understand the needs of the community. When collecting the information, the leader should also listen to the needs of minority groups. To succeed in the negotiation, participants thought that developing close relations in the community was also important.

Most of the work of a leader involves dealing with other persons, so it is necessary to negotiate with them well. (P7)

The ability to negotiate in a way I can get important information. This means I can not be disliked, etc. (P18)

Management capability

The ability to run a clinic, medical unit or medical association is thought to be important. Simply having good medical skills will not make a doctor a leader in the community.

The leader must have management knowledge and the capacity to think from a management viewpoint. They must also be able to raise money for community projects and activities.

The ability to think about finances. (P6)

In the future, if a leader is not good at management nothing will be possible. (P9)

Enjoy oneself

The doctors interviewed felt an attraction to community medicine; that it is fun and challenging for them. Leaders do not always feel happy, but it is important to have the mindset that they will enjoy everything and value the events that they feel are enjoyable when shared with other members of the community.

I am rooted in the community and enjoy its activities. (P16)

My mindset is that I will enjoy everything. (P19)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate the competencies that are necessary to leaders in the field of community medicine. We identified six competencies that are necessary to leadership in the Japanese medical setting. ‘Developing a long-term perspective’, ‘team building that includes residents and local government officials’ and ‘enjoying oneself’ are examples of specific competencies that would be useful for educational curricula designed to develop leaders in the field of community medicine.

In previous reports,11–13 team building and management of the team, establishing a vision, inspiring a shared vision and communication were reported to be common attributes of general medical leadership. From another perspective, according to Dr Sarah Elaine Eaton in Literacy, Languages and Leadership, “A community leader’s job is not to take on all the problems of the world themselves and fix everything, but rather to work together with everyone in the community, to mobilize and guide others, to facilitate solutions and things about the long-term health of the community and its people”.24 This is related to our competency finding indicating the need for medical ability to manage difficult cases. She also reported 10 characteristics that are particular to excellent community leaders: (1) maximise individuals’strengths, (2) balance the needs of your leadership group, (3) work as a team, (4) mobilise others, (5) pitch in, (6) practice stewardship, (7) be accountable to the community, (8) think forward, (9) recruit and mentor new leaders and (10) walk beside, do not lead from above. Furthermore, nine factors for community leadership competencies in the northeast of USA were reported by Gerald A Strand: (1) problem solving ability, (2) demeanour, (3) budgeting and supervisory competencies, (4) needs assessment competencies, (5) promoting feelings of importance in community members, (6) group organisation and communication competencies, (7) organisation leadership competencies, (8) leadership attitude/principles and (9) management of change competencies.25 From these reports and the outcomes of our study, the competencies required of physician leaders were almost same as those of community leaders. Although in previous reports team building was one of the competencies of leaders, residents and members of the local government were not included in the team. We think that residents are the centre of a community and that the local government should play an important role, thus including residents and local government officials in the team is of utmost importance.

Notably, personal attitude was included in the competencies; for example, model the way, encourage the heart. We additionally found that our participants identified enjoyment as a key factor. They felt that community leaders enjoyed their work and found it challenging.

Mohd-Shamsudin and Chuttipattana reported that the success of any organised health programme depends on effective management,26 but that health systems worldwide face a lack of competent management at all levels. He identified six clinical managerial competencies within the context of the rural primary care sector: visionary leadership; assessment, planning and evaluation; promotion of health and prevention of disease; information management; partnership and collaboration and communication. Our data also demonstrated that management ability is an important competency. Of his proposed competencies, promotion of health and prevention of disease were lacking in our study. However, we think that in addition to treatment, prevention of disease is an important work for a community leader.

Hana and Rudebeck explored the personal experiences of and conceptions regarding leadership in rural primary care in Northern Norway.27 They identified three main categories: demands and challenge, personal quantification and exercising leadership. In exercising leadership, they described a vision of a style of coaching and coordination leadership and the display of communication skills, decision-making ability, result focusing and ad hoc solutions. These are all included in our competencies. In the Hana and Rudebeck paper, the participants felt that they were not prepared for leadership and not taking enough leadership training. One of our competencies is having a long-term perspective, which includes cultivation of future generations of doctors and other medical staff members. Furthermore, in demands and challenges, they found that a lack of doctors resulted in less time for leadership. Hence, we believe that cultivation of future generations of doctors is an important competency for community leaders.

A limitation of this study is that we could interview only in a Japanese setting, so we cannot say if the six competencies that emerged can be applied in other areas of the world. Further, the interviewer belongs to the General Medicine Department. Thus, there is potential bias in his perception of community medicine.

Conclusions

We demonstrated six competencies that are needed by leaders in the field of community medicine. The results of this study will contribute to designing a curriculum that will help develop such leaders.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MKa planned the study, interviewed the doctors and wrote the paper. MKi did the transcripts of semistructured interviews and analysed and coded them with MKa. MN and MY discussed and agreed or disagreed with the results to give a consensus agreement.

Funding: This study was supported, by a research grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (grant number 26460605).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. UNICEF. Primary health care report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, WHO Alma Ata. 1978.

- 2. WHO. Global strategy for health for all by the year 2000 (No.3), p.15 Health For All Series: World Health Organization, 1981. (accessed 7 July 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Markuns JF, Fraser B, Orlander JD. The path to physician leadership in community health centers: implications for training. Fam Med 2010;42:403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Watmough S. An evaluation of the impact of an increase in community-based medical undergraduate education in a UK medical school. Educ Prim Care 2012;23:385–90. 10.1080/14739879.2012.11494149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Techonology: Model CoreCurriculum. 2011.

- 6. Iwasaki T, Takeyama Y, Iki M, et al. The changes in students' consiciousness about community medicine during our program. Med Educ 2011;42:101–12. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yuki G. Leadership in organization. Upper Saddle River. NJ: Pearson Education, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reinertsen JL. Physicians as leaders in the improvement of health care systems. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:833–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-128-10-199805150-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAlearney AS. Using leadership development programs to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:319–31. 10.1097/00115514-200809000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee TH. Turning doctors into leaders. Harv Bus Rev 2010;88:50–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz RW, Pogge C. Physician leadership: essential skills in a changing environment. Am J Surg 2000;180:187–92. 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00481-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kouzeu JM, Posner BZ. The leadership challenge: how to keep getting extraordinary things done in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dine CJ, Kahn JM, Abella BS, et al. Key elements of clinical physician leadership at an academic medical center. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:31–6. 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00017.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boelen C. The five-star doctor: an asset to health care reform? www.who.int/hrh/en/HRDJ_1_1_02.pdf (accessed 7 July 2017).

- 15. Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, et al. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med 2002;77:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malone K, Supri S. A critical time for medical education: the perils of competence-based reform of the curriculum. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2012;17:241–6. 10.1007/s10459-010-9247-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huddle TS, Heudebert GR. Taking apart the art: the risk of anatomizing clinical competence. Acad Med 2007;82:536–41. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varkey P, Peloquin J, Reed D, et al. Leadership curriculum in undergraduate medical education: a study of student and faculty perspectives. Med Teach 2009;31:244–50. 10.1080/01421590802144278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Sullivan H, McKimm J. Medical leadership and the medical student. Br J Hosp Med 2011;72:346–9. 10.12968/hmed.2011.72.6.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quince T, Abbas M, Murugesu S, et al. Leadership and management in the undergraduate medical curriculum: a qualitative study of students' attitudes and opinions at one UK medical school. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005353 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cadieux DC, Lingard L, Kwiatkowski D, et al. Challenges in translation: lessons from using business pedagogy to teach leadership in undergraduate medicine. Teach Learn Med 2017;29:207–15. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1237361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Size T. Leadership development for rural health. N C Med J 2006;67:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glasedr B. The constant comparative method of quantitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sarah Elaine Eaton 10 characteristics of community leaders. http://wp.me/pNAh3-1tI (accessed 7 July 2017).

- 25. Strand GA. Community leadership competencies in the Northeast US: implications for training public health educators. Am J Public Health 1981;71:397–402. 10.2105/AJPH.71.4.397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mohd-Shamsudin F, Chuttipattana N. Determinants of managerial competencies for primary care managers in Southern Thailand. J Health Organ Manag 2012;26:258–80. 10.1108/14777261211230808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hana J1, Rudebeck CE. Leadership in rural medicine: the organization on thin ice? Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.