Abstract

Introduction

Sleep disturbance is commonly observed in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Disturbed sleep may exacerbate the core symptoms of ASD. Behavioural interventions and supplemental melatonin medication are traditionally used to improve sleep quality, but poor sustainability of behavioural intervention effects and use of other medications that metabolise melatonin may degrade the effectiveness of these interventions. However, several studies have suggested that physical activity may provide an effective intervention for treating sleep disturbance in typically developing children. Thus, we designed a study to examine whether such an intervention is also effective in children with ASD. We present a protocol (4 December 2017) for a jogging intervention with a parallel and two-group randomised controlled trial design using objective actigraphic assessment and 6-sulfatoxymelatonin measurement to determine whether a 12-week physical activity intervention elicits changes in sleep quality or melatonin levels.

Methods and analysis

All eligible participants will be randomly allocated to either a jogging intervention group or a control group receiving standard care. Changes in sleep quality will be monitored through actigraphic assessment and parental sleep logs. All participants will also be instructed to collect a 24-hour urine sample. 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, a creatinine-adjusted morning urinary melatonin representative of the participant’s melatonin levels, will be measured from the sample. All assessments will be carried out before the intervention (T1), immediately after the 12-week intervention or regular treatment (T2), 6 weeks after the intervention (T3) and 12 weeks after the intervention (T4) to examine the sustainability of the intervention effects. The first enrolment began in February 2018.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained through the Human Research Ethics Committee, Education University of Hong Kong. The results of this trial will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: physical activity, sleep, children with autism spectrum disorders, melatonin

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This protocol is the first randomised controlled trial examining the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorders.

The proposed study uses bioanalysis to examine the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality.

The findings of the study cannot be generalised to children with typical development.

Introduction

The WHO defines autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as a group of complex brain development disorders1 that often presents at a young age.1 2 ASD is characterised, in varying degrees, by significant impairments in social interaction and communication accompanied by restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour.2 In Hong Kong, an estimated 0.3%–0.7% of children below the age of 15 years have been diagnosed with ASD by professionals.3 Compared with typically developing (TD) children, the likelihood of sleep disturbance is higher in children with ASD,4 5 evident in 40%–80% of children with ASD5–8 compared with 20%–45% in TD children.9 10 The number of reports of children’s sleep disturbance from parents has also been shown to be consistently higher among parents of children with ASD (50%–80%) compared with those of TD children (10%–25%).9 11 The most frequently reported sleep disturbances include delayed sleep onset, difficulty in sleep maintenance and insufficient sleep duration (SD).4 11 12 Sleep disturbance has detrimental effects on cognitive development (eg, impairments in learning performance13 and memory consolidation14) and daily functioning (eg, increased stereotypy15 and overall autistic behaviour16) of children with ASD. Together with cognitive deficits and behavioural problems associated with ASD, the negative impacts of sleep disturbance may further worsen the general well-being of affected children. In addition, poor sleep patterns in children with ASD have been associated with adverse sleep quality and higher levels of stress for parents.17 18

Given the high prevalence rate and negative consequences of sleep disturbances in children with ASD, effective intervention strategies are required. Currently, behavioural intervention and medication are the two main strategies for ameliorating sleep disturbances in children with ASD.19 20 Considering the undesirable side effects of medication, such as morning drowsiness and increased enuresis, parents generally prefer not to use drugs to treat their children.21 Therefore, behavioural intervention is recommended as first-line therapy.18 20 Various forms of behavioural intervention (eg, extinction, faded bedtime) have been developed to treat sleep disturbances among children with ASD, the most common of which is extinction (removal of reinforcement to reduce a behaviour).22 23 Extinction has been well documented as an effective technique to treat sleep disturbances, potentially providing a method for initiating and maintaining sleep in children with ASD.22 23 However, this method can be very stressful for children and parents, and can result in a temporary increase in negative behaviour (ie, extinction burst).22 24 In addition, extinction interventions are intensive, and their implementation requires tremendous support and resources, and therefore may not be cost-effective.23 In addition, research into these interventions has typically been limited to small-case or single-subject design studies, with procedures that are difficult to follow.22 Therefore, the efficacy of these interventions remains unclear.

Meanwhile, a significant body of research has investigated the effects of physical activity (PA) on sleep in a normal population. Several meta-analytical review studies provided compelling evidence that exercise has positive impacts on sleep quality.25–27 For example, a recent meta-analysis of 66 studies (n=284) by Kredlow et al 26 examined the effects of acute and regular exercise on sleep. Their findings indicated that both acute and regular exercise could increase total sleep time, improve sleep onset latency (SOL) and sleep efficiency (SE), reduce rapid eye movement and promote slow wave sleep.

Although PA has been shown to be beneficial to sleep quality, most studies have been conducted on healthy adults and good sleepers25 27 and only a small number of studies have been conducted in the child population.28 29 Recently, two small-scale studies were conducted to explore the impact of PA on sleep in children with ASD.30 31 In one study, Wachob and Lorenzi30 used accelerometers to objectively measure subjects’ PA level and sleeping quality (ie, SE and wake after sleep onset (WASO)) in 10 children with ASD. The results revealed a negative relationship between the average time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and average WASO time, and a positive relationship between average sedentary time and average SE percentages. In another study, Brand et al 31 found a similar association between PA and sleep quality. In that study, researchers asked 10 children with ASD to participate in thrice-weekly 30 min sessions of bicycle workout followed by 30 min of coordination and balance training. A sleep encephalography device was used to objectively measure several sleep parameters (eg, total sleep time, sleeping period and SE). The results revealed that physical exercise was associated with increased SE, shortened SOL and decreased WASO time.31

Given the benefits of PA on sleep, it has been suggested that PA may provide an alternative treatment for sleep disturbances in children with ASD.30 31 However, it remains unclear whether the effect of exercise-based interventions can be sustained. Also, precautions should be taken when interpreting the results because of the small sample sizes and lack of control conditions.30 31 More importantly, the mechanism of how PA impacts on sleep remains unclear, particularly in children with ASD. Indeed, it is important to understand such mechanisms to design an effective PA intervention for sleep disturbances among children with ASD. In the normal population, several mechanism models (eg, the thermoregulatory hypothesis,32 body restoration theory33 and melatonin-mediated mechanism34) have been proposed. Of particular interest to the current study is the melatonin-mediated mechanism model, which suggests that PA affects the circadian rhythm by altering melatonin levels.35

Melatonin, a natural hormone produced by the pineal gland, functions as a key regulator of the circadian rhythm and promotes sleep onset and sleep maintenance.36 Secretion of melatonin normally increases shortly after darkness, peaks in the middle of the night and falls slowly during the early morning hours.37 This hormonal response allows for maintaining a normal circadian rhythm and sleeping through the night. Compared with TD children, melatonin levels have been reported to be lower5 38 in some children with ASD, although no such difference was shown in two other studies.39 40 To counter this melatonin deficit, supplemental melatonin is commonly used to treat insomnia in children with ASD.41 Recently, researchers suggested that melatonin levels could also be altered by PA.42 In one experiment, Marrin et al 42 asked seven healthy participants to complete a moderate-intensity morning cycling exercise while measuring their salivary melatonin concentration at different time points: baseline, during exercise, after exercise and recovery. The results revealed that participants’ melatonin levels significantly increased during and after exercise compared with those at baseline and recovery. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between PA, melatonin and sleep, particularly in children with ASD. Therefore, the mechanisms by which PA impacts on sleep in children with ASD remain unclear. To examine this question, here we propose a new study protocol, which began enrolment in February 2018.

Objectives

This study protocol has two objectives: (1) to examine the associations between PA, melatonin and sleep quality in children with ASD, to ultimately elucidate how PA impacts on sleep in children with ASD, from the perspective of the melatonin-mediated mechanism model; and (2) to examine the possible sustained effect of PA on improved melatonin secretion and sleep quality in children with ASD. We hypothesise that PA can improve sleep quality in children with ASD by increasing their endogenous melatonin levels, and these beneficial effects can be sustained.

Methods/design

Study design

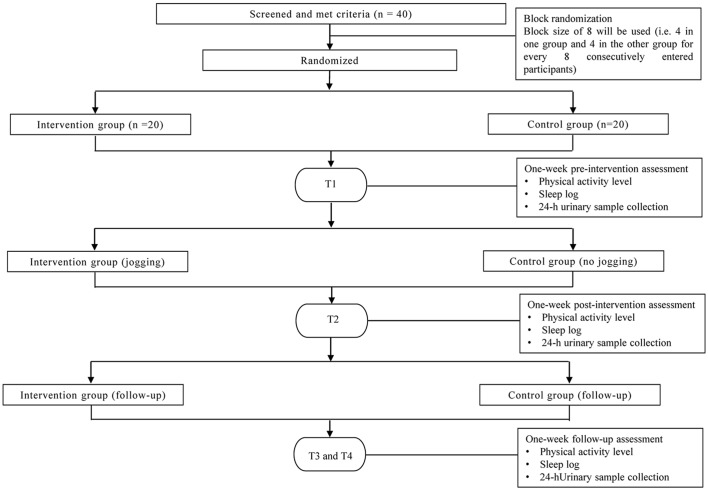

The proposed study will have a parallel, two-group randomised controlled trial (RCT) design, with equal allocation of participants to the intervention and control groups (1:1). A flow diagram of the study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the proposed study.

Data collection

Each participant will attend four 1-week assessments, where we will assess their habitual sleep patterns: before the intervention (T1), immediately after the intervention (T2), 6 weeks after and 12 weeks after the intervention (T3 and T4, respectively). T1 and T2 represent the preintervention and postintervention, respectively. T3 serves as the 6-week follow-up and T4 serves as the 12-week follow-up.

Participants

Children will be screened using the following inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria are: (1) 9–12 years of age; (2) prepuberty or early puberty as indicated by Tanner stage I or II; (3) ASD diagnosis from a physician based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V);43 (4) non-verbal IQ over 40; (5) able to follow instructions; (6) physically able to participate in the intervention; (7) no additional regular participation in physical exercise other than school physical education (PE) classes for at least 6 months prior to the study; (8) no concurrent medication for at least 6 months before the study or any prior melatonin treatment; and (9) sleep difficulties, including sleep onset insomnia and frequent and prolonged nightwaking and/or early morning awakening (see Giannotti et al 44 for definitions) reported by parents.

The exclusion criteria are: (1) one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders, as established by a structured interview based on DSM-V; (2) other medical conditions that limit PA capacity (eg, asthma, seizure, cardiac disease); and (3) a complex neurological disorder (eg, epilepsy, phenylketonuria, fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis). All screening will be carried out by a psychologist and a physician.

Intervention

Intervention group

The intervention is a 12-week jogging programme consisting of 24 sessions (two sessions per week, 30 min per session) in a hall/gymnasium of each participating school. The total of 24 sessions was selected based on previous studies involving jogging in this population.45 46 Each intervention session will be conducted in the morning by a trained research assistant and student helpers. The staff-to-participant ratio for both groups is 1:2 to 1:1 depending on the attendance. The research assistant and student helpers must be majoring in PE or adapted PE and must have experience with children with ASD. Each intervention session will be conducted in an identical format, comprising three activities: warm-up (5 min), jogging (20 min) and cool-down (5 min). In the jogging activity group, participants will be asked to jog around an activity circuit (57 m×50 m) marked with four red cones together with the research staff. The activity circuit will be set up in an outdoor sports ground or indoor gymnasium depending on the weather and the arrangement of the participating schools. Participants are required to run at a moderate intensity level. The intensity level of jogging will be objectively measured by asking participants to wear a heart rate (HR) monitor (Polar H1) during each jogging session. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,47 MVPA is achieved with a target heart rate (THR) above 60% of the maximum HR (subtracting the participant’s age from 220).48 Considering the low PA level of children with ASD,49 PA with an HR above 50% of the maximum HR should be considered MVPA. The intervention is considered successful if the participants can maintain their THR for 15 min or above throughout the jogging session. A Polar device will also be used to calculate how long the participants are within their THR (ie, 50% or above the maximum HR). Meanwhile, jogging is chosen because it is one of the most common exercises studied with regard to ASD50 and can serve as endurance training, which is shown to be beneficial for sleep.27 Participants will be positively reinforced verbally with compliments for their efforts in jogging and their daily and weekly improvements will be visualised through graphs and scales kept at home in the child’s bedroom.31 After the intervention, the participants will be required to follow their normal daily routine without participating in any additional PA/exercise programme (except the 60 min weekly PE classes provided by school) throughout the follow-up period (T2–T4).

Control group

Participants in the control group will receive no physical intervention (ie, jogging programme) and will be required to follow their daily routine without participating in any additional PA/exercise programme except the regular PE classes throughout the whole study period (T1–T4).

Study measures

Before the initial assessment, participants’ parents will be asked to provide demographic data and a brief developmental history. Both participants and their parents will undertake T1, T2, T3 and T4, where the following measurements will be carried out.

Primary outcome measures

Sleep

Four sleep parameters including SOL (length of time taken to fall asleep, expressed in minutes), SE (actual sleep time divided by time in bed, expressed as a percentage), WASO (length of time they were awake after sleep onset, expressed in minutes) and SD (total SD in hours and minutes) will be objectively measured using a GT3X accelerometer.30 Participants will be asked to wear the device on their non-dominant wrist for 7 consecutive days (Monday to Sunday). The non-wear time is defined as 60 min of consecutive zeros with a 2 min spike tolerance.30 The night (22:00–07:00) will be considered invalid if the wear time is less than 8 hours and will be excluded from the analysis. In addition, participants’ sleep patterns will be logged by their parents using the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, which is a validated 45-item parent-administered questionnaire to examine the sleep patterns of young children,51 including children with ASD.30 Parents will be asked to recall specific sleep patterns of their children over the assessment weeks (T1, T2, T3 and T4). Finally, parents will also be asked to log the bedtime, sleep latency, sleep start, sleep end, wake-up time and assumed sleep length in a sleep log for the whole assessment week. The sleep log is used as part of the refined sleep algorithm in actigraph data analysis to identify nocturnal sleep and to exclude non-wear time/wakefulness.52

Melatonin level

All participants will be instructed to collect a 24-hour urine sample. 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, a creatinine-adjusted morning urinary melatonin that is considered representative of melatonin level, will be measured from the sample.53 The weekend has been chosen to allow the participants to stay at home for sample collection. All urine samples will be collected using 24-hour urine bottles containing 0.1 L of 0.5 M hydrochloric acid as a preservative. Upon completion, the research assistant will immediately collect the urine sample from the participants’ homes and bring it to the Sleep Assessment Unit of Sha Tin Hospital. The urine sample will be stored at −80° before analysis.

Secondary outcome measure

PA level

The PA level of the participants will also be measured as secondary data to examine its relationship to sleep, as suggested by previous studies.5 30 This measurement will be conducted using the same accelerometer (ie, GT3X). The data used for analysis are the times spent in sedentary activity and MVPA based on the default energy expenditure algorithm in the accelerometer device.54 The day (07:00–21:00) will be considered invalid if the wear time is less than 10 hours and will then be excluded from the analysis.

Sample size

A pilot study on improving sleeping quality among children with ASD31 revealed that PA had a notable effect (corresponding to a Cohen’s d of approximately 1.0) on improving sleeping quality. Given this effect size, a sample of 16 participants per group is required to achieve a power of 80% and a level of significance of 5%. Assuming a 20% attrition rate, 20 participants will be recruited per group. They will be recruited from three local special schools with existing research links to the principal investigator (PI) and collaborators. More special schools will be invited to join the research project if there is inadequate participant enrolment among the three participating schools.

Randomisation

After screening, all eligible participants will be randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. To ensure equal allocation ratios for the intervention and control groups, block randomisation55 will be used. A block size of eight will be used in the proposed study (ie, four in one group and four in the other group for every eight consecutively entered participants). The block randomisation process will be performed by a trained research assistant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public will not be involved in the study.

Blinding

The person responsible for analysing the sleep parameters and melatonin level will be blinded to the group assignment.

Ethics and dissemination

Prior to the study, information about the study will be provided to all participants and their parents with the distribution of written consent forms (see online supplementary appendix I). The consent forms will be collected from the participants and their parents by a PE teacher at each participating school. All participants and their parents will be informed that withdrawal at any time will not result in any adverse consequences. All sets of data will be encrypted with passwords. To prevent any leakage of sensitive information, only the PI and collaborators will have access to the data sets. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, The Education University of Hong Kong (reference number 2016-2017-0155). The results of the study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Findings of the study will also be shared with other university and non-governmental organisations in Hong Kong that specialise in autism by means of a formal dissemination seminar.

bmjopen-2017-020944supp001.pdf (157.4KB, pdf)

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses will be conducted using SPSS (V.23.0) for Windows (SPSS) to assess sleep; multilevel regression or a generalised estimating equation will be used to assess the effect of the PA intervention, the effect of time and their interaction effect on sleep outcomes and melatonin level outcomes. Two potential confounding variables (ie, average time spent in daily sedentary activity and average time spent in daily MVPA) will be used as covariates because they may be closely related to sleep quality.56 The effect size will be reported as a Cohen’s d. Bonferroni adjustment will be used to control for possible type I error inflation caused by multiple comparisons. The intention-to-treat approach will be used to handle any missing data.

Discussion

This study is the first RCT designed to examine the effectiveness of PA intervention on sleep disorder among children with ASD. In addition, it is the first study designed to investigate whether the melatonin-mediated mechanism is a potential underlying pathway by which PA impacts on sleep in children with ASD. The results obtained in this study will potentially have two significant implications. First, if the intervention is effective, doctors can prescribe PA to children with ASD who are not able to take drugs based on the notion of ‘exercise as medicine’. Second, the melatonin-mediated mechanisms investigated in this study could lead to further investigation of the interaction between PA and melatonin in any population suffering from sleep disturbance. Such research could include a comparison of the effectiveness of PA and supplemental melatonin interventions on sleep quality in populations suffering from sleep disorders and the manipulation of different PA intervention parameters (eg, intensity, frequency and time) on melatonin level and sleep quality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Knight, MSc, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: ACYT and JZ conceived the study and designed the study protocol. PHL assisted in defining the statistical analysis and provided input for the manuscript. EWHL provided critical comment on implementation of the participant screening protocol. All authors contributed to, read drafts of and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Early Career Scheme of Research Grant Council (grant number: 28602517), University Grants Committee of HKSAR Government (No 28602517).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee, EdUHK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Questions and answers about autism spectrum disorders (ASD). 2016. http://www.who.int/features/qa/85/en/ (accessed 12 Aug 2016).

- 2. Rapin I, Tuchman RF. Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am 2008;55:1129–46. 10.1016/j.pcl.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yip L. Update on autism. Public Health Epidemiol Bull 2012;21:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Ivanenko A, et al. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med 2010;11:659–64. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu X, Hubbard JA, Fabes RA, et al. Sleep disturbances and correlates of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2006;37:179–91. 10.1007/s10578-006-0028-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sivertsen B, Posserud MB, Gillberg C, et al. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum problems: a longitudinal population-based study. Autism 2012;16:139–50. 10.1177/1362361311404255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orsmond GI, Seltzer MM. Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2007;13:313–20. 10.1002/mrdd.20171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldman SE, Richdale AL, Clemons T, et al. Parental sleep concerns in autism spectrum disorders: variations from childhood to adolescence. J Autism Dev Disord 2012;42:531–8. 10.1007/s10803-011-1270-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fricke-Oerkermann L, Plück J, Schredl M, et al. Prevalence and course of sleep problems in childhood. Sleep 2007;30:1371–7. 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calhoun SL, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in a general population sample of young children and preadolescents: gender effects. Sleep Med 2014;15:91–5. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Souders MC, Mason TB, Valladares O, et al. Sleep behaviors and sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorders. Sleep 2009;32:1566–78. 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richdale AL, Schreck KA. Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Med Rev 2009;13:403–11. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, et al. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev 2010;14:179–89. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev 2006;10:323–37. 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mazurek MO, Sohl K. Sleep and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2016;46:1906–15. 10.1007/s10803-016-2723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schreck KA, Mulick JA, Smith AF. Sleep problems as possible predictors of intensified symptoms of autism. Res Dev Disabil 2004;25:57–66. 10.1016/j.ridd.2003.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doo S, Wing YK. Sleep problems of children with pervasive developmental disorders: correlation with parental stress. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48:650–5. 10.1017/S001216220600137X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xt Y, Lam HS, Ct A, et al. Extended parent-based behavioural education improves sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder. Hong Kong J Ped 2015;20:219–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richdale AL. Sleep problems in autism: prevalence, cause, and intervention. Dev Med Child Neurol 1999;41:60–6. 10.1017/S0012162299000122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malow BA, Byars K, Johnson K, et al. A practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2012;130(Suppl 2):S106–S124. 10.1542/peds.2012-0900I [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bramble D. Consumer opinion concerning the treatment of a common sleep problem. Child Care Health Dev 1996;22:355–66. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1996.tb00438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vriend JL, Corkum PV, Moon EC, et al. Behavioral interventions for sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: current findings and future directions. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:1017–29. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiskop S, Richdale A, Matthews J. Behavioural treatment to reduce sleep problems in children with autism or fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neuro 1999;47:94–104. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2005.tb01097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lancioni GE, O’Reilly MF, Basili G. Review of strategies for treating sleep problems in persons with severe or profound mental retardation or multiple handicaps. Am J Mental Retard 1999;104:170–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Driver HS, Taylor SR. Exercise and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 2000;4:387–402. 10.1053/smrv.2000.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kredlow MA, Capozzoli MC, Hearon BA, et al. The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med 2015;38:427–49. 10.1007/s10865-015-9617-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Youngstedt SD, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effects of acute exercise on sleep: a quantitative synthesis. Sleep 1997;20:203–14. 10.1093/sleep/20.3.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lundahl A, Nelson TD, Van Dyk TR, et al. Psychosocial stressors and health behaviors: examining sleep, sedentary behaviors, and physical activity in a low-income pediatric sample. Clin Pediatr 2013;52:721–9. 10.1177/0009922813482179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stone MR, Stevens D, Faulkner GE. Maintaining recommended sleep throughout the week is associated with increased physical activity in children. Prev Med 2013;56:112–7. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wachob D, Lorenzi DG. Brief report: influence of physical activity on sleep quality in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45:2641–6. 10.1007/s10803-015-2424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brand S, Jossen S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al. Impact of aerobic exercise on sleep and motor skills in children with autism spectrum disorders - a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015;11:1911–20. 10.2147/NDT.S85650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Keeping cool: a hypothesis about the mechanisms and functions of slow-wave sleep. Trends Neurosci 1990;13:480–7. 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90081-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Adam K, Oswald I. Protein synthesis, bodily renewal and the sleep-wake cycle. Clin Sci 1983;65:561–7. 10.1042/cs0650561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atkinson G, Edwards B, Reilly T, et al. Exercise as a synchroniser of human circadian rhythms: an update and discussion of the methodological problems. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007;99:331–41. 10.1007/s00421-006-0361-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee H, Kim S, Kim D. Effects of exercise with or without light exposure on sleep quality and hormone reponses. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem 2014;18:293–9. 10.5717/jenb.2014.18.3.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wirojanan J, Jacquemont S, Diaz R, et al. The efficacy of melatonin for sleep problems in children with autism, fragile X syndrome, or autism and fragile X syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:145–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Melatonin in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53:783–92. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krakowiak P, Goodlin-Jones B, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: a population-based study. J Sleep Res 2008;17:197–206. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Veatch OJ, Goldman SE, Adkins KW, et al. Melatonin in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: How Does the Evidence Fit Together? J Nat Sci 2015;1:125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goldman SE, Adkins KW, Calcutt MW, et al. Melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorders: endogenous and pharmacokinetic profiles in relation to sleep. J Autism Dev Disord 2014;44:2525–35. 10.1007/s10803-014-2123-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arendt J. Importance and relevance of melatonin to human biological rhythms. J Neuroendocrinol 2003;15:427–31. 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marrin K, Drust B, Gregson W, et al. Diurnal variation in the salivary melatonin responses to exercise: relation to exercise-mediated tachycardia. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011;111:2707–14. 10.1007/s00421-011-1890-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Cerquiglini A, et al. An open-label study of controlled-release melatonin in treatment of sleep disorders in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2006;36:741–52. 10.1007/s10803-006-0116-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petrus C, Adamson SR, Block L, et al. Effects of exercise interventions on stereotypic behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiother Can 2008;60:134–45. 10.3138/physio.60.2.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kern L, Koegel RL, Dyer K, et al. The effects of physical exercise on self-stimulation and appropriate responding in autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord 1982;12:399–419. 10.1007/BF01538327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Measuring physical activity intensity: target heart rate and estimated maximum heart rate. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/heartrate.htm (accessed 26 Mar 2017).

- 48. Londeree BR, Moeschberger ML. Effect of age and other factors on maximal heart rate. Res Q Exerc Sport 1982;53:297–304. 10.1080/02701367.1982.10605252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pan CY, Chu CH, Tsai CL, et al. The impacts of physical activity intervention on physical and cognitive outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2017;21:190–202. 10.1177/1362361316633562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lang R, Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, et al. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2010;4:565–76. 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000;23:1–9. 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Barreira TV, Schuna JM, Mire EF, et al. Identifying children’s nocturnal sleep using 24-h waist accelerometry. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:937–43. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. ActiGraph. What is MVPA and how I can view in ActiLife. 2016. https://help.theactigraph.com/entries/22148365-What-is-MVPA-and-how-can-I-view-it-in-ActiLife- (accessed 2 Sep 2017).

- 54. Schernhammer ES, Kroenke CH, Dowsett M, et al. Urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin levels and their correlations with lifestyle factors and steroid hormone levels. J Pineal Res 2006;40:116–24. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Efird J. Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:15–20. 10.3390/ijerph8010015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kline CE, Crowley EP, Ewing GB, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2011;34:1631–40. 10.5665/sleep.1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020944supp001.pdf (157.4KB, pdf)