Abstract

Introduction

Even after ‘back-to-sleep’ campaigns, sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) continues to be the leading cause of death for infants 1 month to 1 year old in developed countries, with devastating social, psychological and legal implications for families. To sustainably tackle this problem and decrease the number of SUIDs, a French SUID registry was initiated in 2015 to (1) inform prevention with standardised data, (2) understand the mechanisms leading to SUID and the contribution of the already known or newly suggested risk factors and (3) gather a multidisciplinary group of experts to coordinate and develop innovative and urgent research in the SUID area.

Methods and analysis

This observational multisite prospective observatory includes all cases of sudden unexpected deaths in children younger than 2 years occurring in the French territory covered by the 35 participating French referral centres. From these cases, various data concerning sociodemographic conditions, death scene, personal and family medical history, parental behaviours, sleep environment, clinical examinations, biological and imagery investigations and autopsy are systematically collected. These data will be complemented as of 2018 with a biobank of diverse biological samples (blood, hair, urine, faeces and cerebrospinal fluid), with other administrative health-related data (health claim reimbursements and hospital admissions) and socioenvironmental data. Insights from exploratory descriptive statistics and thematic analysis will be combined for the design of targeted strategies to effectively reduce preventable infant deaths.

Ethics and dissemination

The French sudden unexpected infant death registry (Observatoire National des Morts Inattendues du Nourrisson registry;OMIN) was approved in 2015 by the French Data Protection Authority in clinical research (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés: number 915273) and by an independent ethics committee (Groupe Nantais d’Ethique dans le Domaine de la Santé: number 2015-01-27). Results will be discussed with associations of families affected by SUID, caregivers, funders of the registry, medical societies and researchers and will be submitted to international peer-reviewed journals and presented at international conferences.

Keywords: sudden unexpected infant death, sudden infant death, France, public health, Observatoire National Des Morts Inattendues Du Nourrisson (OMIN), registry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The French sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) registry is the first research programme combining French SUID referral centres and a multidisciplinary group of experts.

The French SUID registry’s innovative design combines prospective data concerning sociodemographic conditions, death scene, medical history, parental behaviours, sleep environment, clinical examinations and autopsy findings along with biological samples and other administrative health-related data to yield a detailed description of SUID cases.

As far as possible, the French SUID registry is using standardised data to facilitate future collaborations with other countries to share best practice, monitor progress and achieve statistical power for future investigations.

The results will help in the design of targeted strategies to effectively reduce preventable infant deaths.

The potential limitations of the French SUID registry are ascertaining the exhaustive inclusion of all SUID cases occurring in France as well as the lack of a concomitant control population.

Introduction

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), a devastating event for families, is defined as death in an infant <1 year old that occurs suddenly and unexpectedly and whose cause is not immediately obvious before investigation.1 After case investigation, including a scene investigation, a review of clinical history and an autopsy, SUID can be attributed to various causes. Death is classified as a sudden infant death syndrome when the thorough postmortem examination fails to identify its cause.2

Much research has been conducted to identify and control risk factors leading SUID to be conceptualised as a multifactorial disorder with multiple mechanisms causing or predisposing its occurrence. A ‘triple-risk’ hypothesis (child vulnerability, critical period in development and exogenous stress factors) has been proposed.3 Subsequent to the discovery of the prone sleep position as a major risk factor, ‘back-to-sleep’ prevention campaigns were conducted in the early 1990s and led to a huge decrease in SUID incidence in many countries. However, in the post ‘back-to-sleep’ era, SUID continues to be the first cause of death for infants 1 month to 1 year old in developed countries, and strategic actions are still needed to sustainably tackle this devastating event.4

An international consensus, The Global Action and Prioritization of Sudden Infant Death (GAPS) Project, has recently provided the international SUID research community with a list of shared research priorities to more effectively work toward explaining and reducing the number of sudden infant deaths.5 Three main themes emerged: (1) a better understanding of mechanisms underlying SUID, (2) ensuring best practices in data collection, management and sharing and (3) a better understanding of target populations and more effective communication of known risk factors. To meet these challenges, the creation of innovative national SUID registries systematically collecting standardised data for every SUID case along with biological samples seems an essential prerequisite.6

Accordingly, in 2015, 35 French SUID referral centres in collaboration with the National Association of Referral Centers for SUID (Association Nationale des Centres Référents de la Mort Inattendue du Nourrisson; ANCReMIN) initiated a French national registry, Observatoire National des Morts Inattendues du Nourrisson (OMIN) to prospectively collect for all French SUID cases a large variety of socioenvironmental, behavioural, clinical, radiological and autopsy data simultaneously with biological samples as well as other health-related administrative data (health claim reimbursements and hospital admissions) concerning children <2 years old and their mothers. The global objective of this registry is to sustainably decrease the number of sudden infant deaths by (1) informing prevention with standardised data, (2) understanding the mechanisms leading to sudden infant death, including the contribution of the already known or newly suggested risk factors, and (3) gathering a multidisciplinary group of experts to coordinate and develop research in the SUID area. This report aims to describe the methodology used to establish and manage this registry.

Design

Study design and population

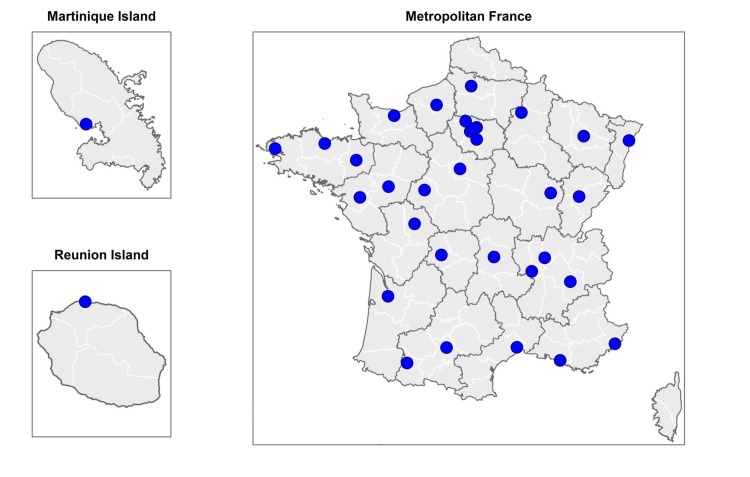

The French SUID registry is an observational prospective registry that over at least a 10-year period (2015–2025) aims to include all SUID cases occurring in the French metropolitan territory plus two overseas islands: La Martinique (Caribbean Sea) and La Réunion (Indian Ocean) (figure 1). Thirty-five French SUID referral centres are participating in this registry.

Figure 1.

Localisation of the 35 referral centres participating in the French SUID registry. SUID, sudden unexpected infant death.

Because in France, a SUID case is legally defined as the sudden unexpected death of a child <2 years old,7 all children younger than 2 years dying in the context of SUID are eligible for the registry. Once all the persons who have parental authority (often one or both parents) are informed that participating is voluntary, data for all children for whom all the persons who have parental authority give informed written consent are included. To ensure completeness in the registry, SUID cases for which at least one of the persons who have parental authority refuses to participate in the registry are recorded with a minimal set of totally anonymous data (reason for refusal, gender and age at death).

Data collection

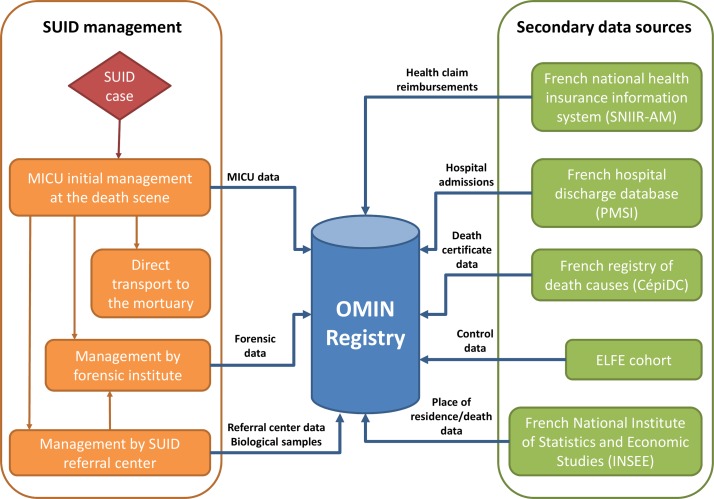

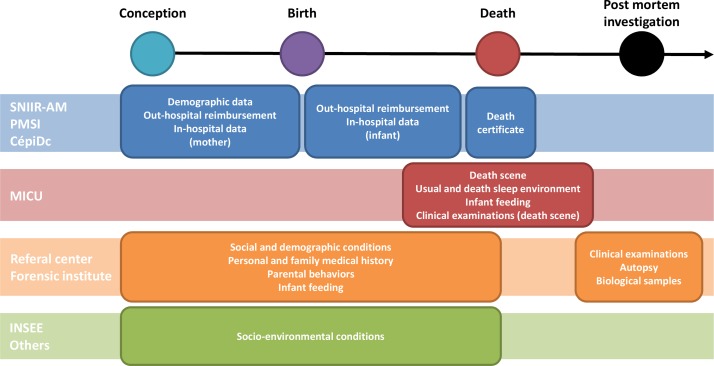

The OMIN is based on a continuous and prospective record of prespecified and standardised information concerning the examinations that should be performed with a SUID case as recommended by the French national health authority.7 The data collection depends on the SUID case trajectory after death as well as the willingness of parents with parental authority to participate. Data are gathered from two different sources: (1) the mobile intensive care unit (MICU) initially in charge of the SUID case on the death scene and (2) the SUID referral centre performing the postmortem exploration to identify the cause of death (figure 2). Additionally, other health-related and socioenvironmental data will be secondary linked as of 2018 to the case in the OMIN database. To ensure that all SUID cases are recorded in the registry, data from the MICU concerning dead children transported directly to the mortuary and not under the control of a referral centre are also collected. In case of forensic investigations (not performed by the referral centres) requested by the Court of Justice, only the MICU data are available. Data collected during the forensic investigation are recorded the second time when the legal procedures are finalised. A summary of the timeline and sources of data collection are presented in figure 3.

Figure 2.

SUID management in France and data collection in the French SUID registry. ELFE, Étude longitudinale française depuis l’enfance; MICU, mobile intensive care unit; OMIN, Observatoire National des Morts Inattendues du Nourrisson; SUID, sudden unexpected infant death.

Figure 3.

Timeline and sources of data collection in the French SUID registry. CépiDC, French registry of death causes; INSEE, National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies; MICU, mobile intensive care unit; PMSI, French hospital discharge database; SUID, sudden unexpected infant death; SNIIR-AM, French national health insurance information system.

Data from MICU and SUID referral centres

Data collected by MICU and SUID referral centres are related to the social and demographic status of children and their parents, personal and family medical history, antenatal and current parental behaviours, child feeding, death scene, usual and death sleep environment, nature and results of clinical examinations at the death scene and the referral centre, nature and results of additional clinical examinations performed in the referral centre, and classification of SUID cases by the medical team based on a national classification and that from Fleming et al 1 (table 1).

Table 1.

Data collected in the French SUID registry

| Collected data | Data sources | |||

| MICU | Referral centre | Forensic institute | Others | |

| Social and demographic conditions | ||||

| Date and place of birth (child) | X | X | ||

| Gender (child) | X | |||

| Nationality (child and parents) | X | |||

| Ethnicity (child and parents) | X | |||

| Age (child and parents) | X | |||

| Educational level (parents) | X | |||

| Employment status (parents) | X | |||

| Marital status (parents) | X | |||

| Socioeconomic level (parents) | X | |||

| Household composition | X | |||

| Type of social security benefits (parents) | X | |||

| Residency address | X | |||

| Personal and family medical history | ||||

| Multiple birth | X | |||

| Gestational age | X | |||

| Birth weight | X | |||

| Small for gestational age | X | |||

| Apgar score at 10 min | X | |||

| Other personal significant events during the perinatal period and early infancy | X | |||

| History of SUID and other sudden deaths in the family | X | |||

| Consanguinity between parents | X | |||

| Vaccination history | X | |||

| Significant medical events in the 72 hours preceding the death | X | |||

| Significant medications in the 72 hours preceding the death | X | |||

| Antenatal and current parental behaviours | ||||

| Smoking | X | |||

| Alcohol consumption | X | |||

| Other drug consumption | X | |||

| Infant feeding | ||||

| Breast feeding | X | |||

| Last meal before death | X | |||

| Death scene | ||||

| Date and time of death | X | |||

| Place of death (address) | X | |||

| Time of last contact | X | |||

| Time of discovery | X | |||

| Arrival time of MICU | X | |||

| Usual and death sleep environment | ||||

| Sleep place | X | |||

| Type of surface | X | |||

| Sleep position last placed/found | X | |||

| Head position | X | |||

| Presence and type of objects on the sleep surface | X | |||

| Thumb and pacifier use | X | |||

| Room heat | X | |||

| Infant dressing | X | |||

| Room sharing | X | |||

| Nature and results of clinical examinations | ||||

| Skin appearance | X | X | X | |

| Body temperature | X | X | X | |

| Weight | X | X | X | |

| Length | X | X | X | |

| Resuscitation manoeuvres | X | X | ||

| Signs of autonomic dysfunction | X | X | X | |

| Blood chemistry | X | X | ||

| Haematology tests | X | X | ||

| Lumbar puncture | X | X | ||

| Microbiology | X | X | ||

| Eye fundi | X | X | ||

| Imagery investigations (CT scan, MRI) | X | X | ||

| Autopsy | X | X | ||

| Classification of SUID cases by the medical team (Fleming) | X | |||

| Biological samples | ||||

| Blood, hair, urine, faeces and CSF | X | |||

| Other data | ||||

| History of health claim reimbursements (child and mother) | X | |||

| History of hospital admissions (child and mother) | X | |||

| Death certificate information | X | |||

| Geocoding of the residency/death address | X | |||

| Urbanicity of residency/death address | X | |||

| Deprivation index of residency/death address | X | |||

| Altitude of residency/death address | X | |||

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MICU, mobile intensive care unit; SUID, sudden unexpected infant death.

Biological sample collection

The collection of biological samples is essential for the SUID research community to better examine the intrinsic mechanisms leading to death and how they interact with environmental risk factors (priority 1 of GAPS Project), identify biomarkers to help pathologists determine the cause of death (priority 5 of GAPS Project) and understand the role of genetic factors in SUID risk (priority 6 of GAPS Project). Accordingly, blood, hair, urine, faeces and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples will be collected as of 2018 from all included SUID cases during the postmortem examination performed at the SUID referral centre. These biological samples will be stored in a network of 28 participating biological resource centres. For blood, a dried blood spot as well as 22 aliquots of blood (2 mL) will be stored for each child: 6 total blood aliquots (EDTA), 8 plasma aliquots (EDTA), 4 blood cell aliquots (EDTA-DMSO) and 4 serum aliquots (dry serum separating tube). Ten aliquots for urine, one for CSF and three for faeces (2 in bottle brusches) will be kept. A lock of hair and two faeces bottlebrushes will be additionally stored. Standardised procedures for biological sample collection will be used, including standardised blood sampling, transport from each site to the central laboratory (<24 hours), aliquoting in cryotubes and storage temperature (ambient temperature, −80°C or −196°C depending on the nature of the biological sample). For timely follow-up of collected biological samples as well as their availability, a central database will be created.

Linkage with secondary sources of data

The completion of a death certificate by a physician is compulsory in France on the occurrence of death. Data from this certificate are gathered by the French registry of death causes (CépiDc) for the whole French population, by gender, age, country of birth and underlying cause of death coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10 discharge diagnosis codes). Legal authorisation was obtained from CépiDc to gather information concerning all deaths in children <2 years old for calculating the exhaustiveness of inclusions in the French SUID registry.

Similarly, health-related information concerning infants and their mothers will be gathered as of 2018 in the French SUID registry from the French national health insurance information system (Système national d’information inter-régimes de l’Assurance maladie, SNIIR-AM) and the French hospital discharge database (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information, PMSI). SNIIR-AM covers the entire French population (65.3 million inhabitants) and contains exhaustive data on all reimbursements for health-related expenditures8 9 including medicinal products such as drugs and outpatient medical and nursing care prescribed or performed by healthcare professionals. PMSI provides detailed medical information on all admissions to French public and private hospitals, including dates of hospital admission and hospital discharge, ICD-10 discharge diagnosis codes and medical procedures during the hospital stay. Data in PMSI and SNIIR-AM were recently made publicly available for pharmacological and epidemiological studies.10 11

To allow for case–control studies to identify risk factors for SUID, data access will be requested in the near future from the Étude longitudinale française depuis l’enfance (ELFE) cohort to use included participants as a control group. ELFE was initiated in 2011 and is a nationally representative cohort of 20 000 children followed from birth to adulthood by use of a multidisciplinary approach to thoroughly characterise the relation between environmental exposures and the socioeconomic context on health and behaviours.12

Population data needed to calculate incidence rates as well as socioenvironmental information concerning the place of residence/death will also be gathered from the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.13

Data management and data analysis

This multicentre registry relies on a web-based system with data being entered into a central database. The system provides security with protected access and complies with French safety policy.14 Data entry and validation is performed as a continuous process. For each SUID case, data extracted from MICU and SUID referral centre records (approximatively 300 variables) are entered directly online by the medical team in charge of the case. A national project manager continuously controls data completeness and validity and notifies the local medical team in case of discrepancies or incomplete data. Routine permanent quality controls, based on regular on-site inspections, are planned, including training of personnel, compliance with study procedures as well as control of data completeness and validity. Automatic data quality controls are performed periodically to control for missing data and value ranges. Once data from the CépiDc are available, recorded data will be compared with those from death certificates to estimate the exhaustiveness of the inclusions in the database. Finally, linkages with previously described secondary data sources will be planned once a year.

In this registry, the number of SUID cases occurring in the French territory per year will determine the recruitment size. On the basis of the referral centres’ experience as well as the last national estimation performed in 2014 by the CépiDc,15 we expect to recruit at least 300 SUID cases each year. A final sample size of about 3000 cases is thus expected for a study period of 10 years.

CIs, means, SDs and frequency distributions will be calculated for all measures. Available data for cases with parental refusals and without a SUID referral centre in charge will be compared with cases with a SUID referral centre in charge. Survival analyses will be used to analyse time-to-event data such as death to identify factors associated with early or late SUID. Multivariable binomial regressions will be used to compare subgroups of SUID children or control children. Multilevel multivariate statistical modelling will also be used to simultaneously study individual and higher-level predictors of outcomes (such as place of residence characteristics). To counteract the potential problem of multiple comparisons, adjustment for statistical significance will be performed when needed. Depending on data and the statistical power available, various other statistical models will also be implemented.

Ethics and dissemination

This project is based on a network that includes the French non-governmental national association of referral centres for SUID (ANCReMIN), 35 governmental French medical referral centres in charge of the dead children and their families, Nantes University Hospital, the Nantes Clinical Investigation Center (CIC 1413) and the Sorbonne Paris Cité Center of Research in Epidemiology and Biostatistics (UMR 1153). All these partners are represented in a steering committee responsible for the organisation of the registry. A coordination unit is in charge to effectively manage the registry and to implement recommendations from the steering committee. Similarly, a scientific committee was created. This committee is responsible for validating all scientific projects from the registry. Data are available for analysis after validation by the scientific committee according to a validated chart of data access. Interested researchers have to comply with the French legislation (ie, apply for authorisation from the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés for treatment of personal health data). Research projects have also to be approved by an independent ethics committee. Scientific use of health insurance claims data requires individual accreditation from the data owner, the French national health insurance.

Results will be discussed with associations of families affected by SUID, caregivers, funders of the registry, medical societies and researchers and will be submitted to international peer-reviewed journals and presented at international conferences.

Discussion

The systematic collection of a large variety of socioenvironmental, behavioural, clinical, imaging and autopsy data simultaneously with biological samples and administrative data concerning both the children and their mothers appeared critical to study or sustainably prevent SUIDs in the post ‘back-to-sleep’ era. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective registry specifically designed to respond to this issue even if large population-based registries with less variety of collected data already exist in other countries.16 17 Because collaboration with such countries is imperative to share best practices, monitor progress and achieve statistical power for future investigations,5 the OMIN involves as far as possible standardised data to facilitate international collaborations such as meta-analyses or original or replication studies.

To be fully operational and to respond to its objectives, the registry will have to manage several challenges. The first will be to recruit a control population simultaneously with SUID cases for risk-factor studies. Indeed, although the already existing ELFE cohort is a potential way to recruit control children, several exposures are lacking in this cohort and the risk of biased selections may not be ascertained from this data source. The second challenge is to ensure the exhaustiveness of including all SUID cases occurring in the French territory. One French referral centres currently do not participate in the OMIN. Also, preliminary tests seem to indicate a possible underinclusion in several participating centres. Data from the CépiDc, when available, will help better quantify the magnitude of this potential bias and implement corrective measures. The third challenge will be to sustainably maintain both the mobilisation of all medical and health actors and caregivers as well as public and private funding, which are essential elements for the success of this project.

In the short term, this registry has the potential to provide an effective response to the SUID major public health issue by identifying underlying mechanisms that can be prevented and by sharing high-quality data to inform best practices and the accurate classification of SUIDs. At the same time, such results will help in mobilising programme planners and policy-makers and in designing targeted strategies to effectively reduce preventable infant deaths.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the families affected by SUID as well as participating centers: Alsace (Strasbourg), Aquitaine (Bordeaux), Auvergne (Clermont Ferrand), Bourgogne (Dijon), Bretagne (Brest, Rennes), Centre (Tours), Champagne Ardenne (Reims), Franche-Comté (Besançon), Ile-de-France (Robert-Debré, Clamart), Languedoc Roussillon (Montpellier), Limousin (Limoges), Lorraine (Vandoeuvre), Midi-Pyrénées (Toulouse), Basse Normandie (Caen), Haute Normandie (Rouen), Pays de la Loire (Nantes, Angers), Picardie (Amiens), Poitou-Charente (Poitiers), Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (Marseille, Nice), Rhône-Alpes (Saint-Etienne, Lyon, Grenoble), Réunion (Saint-Denis), Antilles-Guyane (Fort-de-France), Saint Brieuc, Tarbes-Vic Bigorre, Corbeil-Essonnes, Bondy, Pontoise, Orléans.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL and MH conceptualised and designed the study and wrote the initial draft of this article. HP, EBH, IH, SdV, GG, MC, CGLG and the OMIN Study Group helped in the conceptualisation and design of the study and critically reviewed this article. CGLG is the guarantor of this article. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The OMIN received grants from Sanofi Pasteur MSD, the French national public health agency (Santé Publique France) and two French parent associations (SA VIE and Naitre et Vivre).

Disclaimer: The sponsors had no role in the study design and the submitted work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: The Observatoire National des Morts Inattendues du Nourrisson (OMIN) registry was registered by the French Data Protection Authority in clinical research (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, CNIL; number 915273) and approved by an ethics committee (Groupe Nantais d’Ethique dans le Domaine de la Santé, number 2015-01-27).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: OMIN Study Group: Patricia Garcia-Meric, Laurence Fayol, Loic De Pontual, Aurélien Galerne, Anne-Marie Teychene-Coutet, Jean-Claude Netter, Gaël Sibille, Fakhreddine Maiz, Mariana Englender, Alain De Broca, Petronela Rachieru-Sourisseau, Christine Guillermet, Julia Pauls-Barsanti, Christiane Le-Bot, Anne-Sophie Trentesau, Djamel Sebbouh, Stéphanie Perez-Martin, Muriel Maegd, Anne-Pascale Michard-Lenoir, Abdelilah Tahir, Béatrice Kugener, Blandine Muanza, Odile Pidoux, Anne Borsa Dorion, Mickael Afanetti, Barbara Tisseron, Anne Rancurel, Lolita Leguay, Caroline Robin, Marie Lebeau, Béatrice Digeon, Bénédicte Vrignaud, Céline Farges, François Lecruit, Michel Dagorne, Jean-Luc Alessandri, Sylvain Samperi, Laurent Balu, Olivier Mory, Audrey Breining, Gilles Duthoit, Elisabeth Daussac, Yasmine Plee, Alain Chantepie, Myriam Bouillo.

Contributor Information

OMIN Study Group:

Patricia Garcia-Meric, Laurence Fayol, Loic De Pontual, Aurélien Galerne, Anne-Marie Teychene-Coutet, Jean-Claude Netter, Gaël Sibille, Fakhreddine Maiz, Mariana Englender, Alain De Broca, Petronela Rachieru-Sourisseau, Christine Guillermet, Julia Pauls-Barsanti, Christiane Le-Bot, Anne-Sophie Trentesau, Djamel Sebbouh, Stéphanie Perez-Martin, Muriel Maegd, Anne-Pascale Michard-Lenoir, Abdelilah Tahir, Béatrice Kugener, Blandine Muanza, Odile Pidoux, Anne Borsa Dorion, Mickael Afanetti, Barbara Tisseron, Anne Rancurel, Lolita Leguay, Caroline Robin, Marie Lebeau, Béatrice Digeon, Bénédicte Vrignaud, Céline Farges, François Lecruit, Michel Dagorne, Jean-Luc Alessandri, Sylvain Samperi, Laurent Balu, Olivier Mory, Audrey Breining, Gilles Duthoit, Elisabeth Daussac, Yasmine Plee, Alain Chantepie, and Myriam Bouillo

References

- 1. Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Pease A. Sudden unexpected death in infancy: aetiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology and prevention in 2015. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:984–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics 2004;114:234–8. 10.1542/peds.114.1.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Filiano JJ, Kinney HC. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model. Biol Neonate 1994;65:194–7. 10.1159/000244052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moon RY. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20162940 10.1542/peds.2016-2940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hauck FR, McEntire BL, Raven LK, et al. Research priorities in sudden unexpected infant death: an international consensus. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20163514 10.1542/peds.2016-3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levieux K, Patural H, Harrewijn I, et al. Sudden unexpected infant death: time for integrative national registries. Arch Pediatr 2018;25:75–6. 10.1016/j.arcped.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haute Autorité de Santé. Prise en charge en cas de mort inattendue du nourrisson (moins de 2ans) - Recommandations Professionnelles - Argumentaire. Saint-Denis, France: Haute Autorité de Santé, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, et al. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2010;58:286–90. 10.1016/j.respe.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moulis G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Palmaro A, et al. French health insurance databases: What interest for medical research? Rev Med Interne 2015;36:411–7. 10.1016/j.revmed.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanf M, Quantin C, Farrington P, et al. Validation of the French national health insurance information system as a tool in vaccine safety assessment: application to febrile convulsions after pediatric measles/mumps/rubella immunization. Vaccine 2013;31:5856–62. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ 2016;353:i2002 10.1136/bmj.i2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vandentorren S, Bois C, Pirus C, et al. Rationales, design and recruitment for the Elfe longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:58 10.1186/1471-2431-9-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE). INSEE internet website. 2017. https://www.insee.fr/en/accueil

- 14. Le service public de la diffusion du droit. Loi relative à l’informatique, aux fichiers et aux libertés. 1978. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000886460

- 15. Pavillon G, Laurent F. Certification et codification des causes médicales de décès. Bull Épidémiologique Hebd 2003;30-31:134–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Camperlengo LT, Kim SY, et al. The sudden unexpected infant death case registry: a method to improve surveillance. Pediatrics 2012;129:e486–93. 10.1542/peds.2011-0854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGarvey CM, O’Regan M, Cryan J, et al. Sudden unexplained death in childhood (1-4 years) in Ireland: an epidemiological profile and comparison with SIDS. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:692–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.