Abstract

Objectives

To describe the demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes of neonates born within 7 days of public ambulance transport to hospitals across five states in India.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Five Indian states using a centralised emergency medical services (EMS) agency that transported 3.1 million pregnant women in 2014.

Participants

Over 6 weeks in 2014, this study followed a convenience sample of 1431 neonates born to women using a public-private ambulance service for a ‘pregnancy-related’ problem. Initial calls were deemed ‘pregnancy related’ if categorised by EMS dispatchers as ‘pregnancy’, ‘childbirth’, ‘miscarriage’ or ‘labour pains’. Interfacility transfers, patients absent on ambulance arrival, refusal of care and neonates born to women beyond 7 days of using the service were excluded.

Main outcome measures: death at 2, 7 and 42 days after delivery.

Results

Among 1684 women, 1411 gave birth to 1431 newborns within 7 days of initial ambulance transport. Median maternal age at delivery was 23 years (IQR 21–25). Most mothers were from rural/tribal areas (92.5%) and lower social (79.9%) and economic status (69.9%). Follow-up rates at 2, 7 and 42 days were 99.8%, 99.3% and 94.1%, respectively. Cumulative mortality rates at 2, 7 and 42 days follow-up were 43, 53 and 62 per 1000 births, respectively. The perinatal mortality rate (PMR) was 53 per 1000. Preterm birth (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.67 to 5.00), twin deliveries (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.10 to 7.15) and caesarean section (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.23) were the strongest predictors of mortality.

Conclusions

The perinatal mortality rate associated with this cohort of patients with high-acuity conditions of pregnancy was nearly two times the most recent rate for India as a whole (28 per 1000 births). EMS data have the potential to provide more robust estimates of PMR, reduce inequities in timely access to healthcare and increase facility-based care through service of marginalised populations.

Keywords: Maternal Medicine, India, Emergency Medical Services (ems), Neonatal Mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a novel, prospective assessment of perinatal mortality in India whose mothers used prehospital services within 7 days of delivery.

Follow-up rates were excellent, with over 99% of patients followed at 7 days.

Overall cumulative mortality rates at 2, 7 and 42 days follow-up were 43, 53 and 62 per 1000 births, respectively.

Generalisability may be limited as it was a convenience sample of a unique prehospital system across multiple states in India.

Limited data regarding variability and quality of hospital management and therapeutics were collected.

Introduction

An estimated 2.6 million stillbirths and 2.7 million neonatal deaths occur globally each year.1 A disproportionate percentage (approximately 99%) of these deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries.2

India accounts for approximately one-quarter of global newborn deaths, with an estimated 7 60 000 neonatal deaths in 2012. While India has made laudable progress in reducing overall child mortality over the past 25 years, similar reductions in neonatal mortality have lagged. As a result, India fell short of the Millennium Development Goal 4 of a two-thirds reduction in under-five mortality from 1990 to 2015.3

Globally, the overall number of neonatal deaths has declined significantly, yet they account for an increasing proportion of under-five deaths.4 5 Attempts to reduce deaths around the time of childbirth have been particularly challenging.6 In 2013, India’s perinatal mortality rate (PMR), or the number of third trimester stillbirths (after 28 weeks gestational age) and neonatal deaths in the first 7 days, was 28 per 1000 total births.7 Most agree that this likely underestimates the overall perinatal mortality given the difficulty in capturing stillbirths and deaths that occur at home.8

Previous research on evidence-based approaches to reducing young infant mortality have included efforts to increase access to preventive and curative antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care.9 To date, however, little attention has focused on the role and quality of prehospital care and transport on describing neonatal outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Prehospital care in India has the potential to capture those deaths that occur at home and are not transferred to the hospital. At the same time, prehospital care increases access to skilled birth attendants and facility-based health services, while also providing early lifesaving interventions during transport that can reduce overall neonatal mortality. Recent data from two states in India demonstrate substantial reductions in neonatal and infant mortality rates associated with prehospital services.10 This study aims to report the perinatal mortality among a cohort of young infants, born to labouring women in five Indian states who were transported by an ambulance service with trained emergency medical technicians (EMTs). Secondarily, we report on the demographic, maternal indicators and clinical management associated with increased rates of perinatal death.

Methods

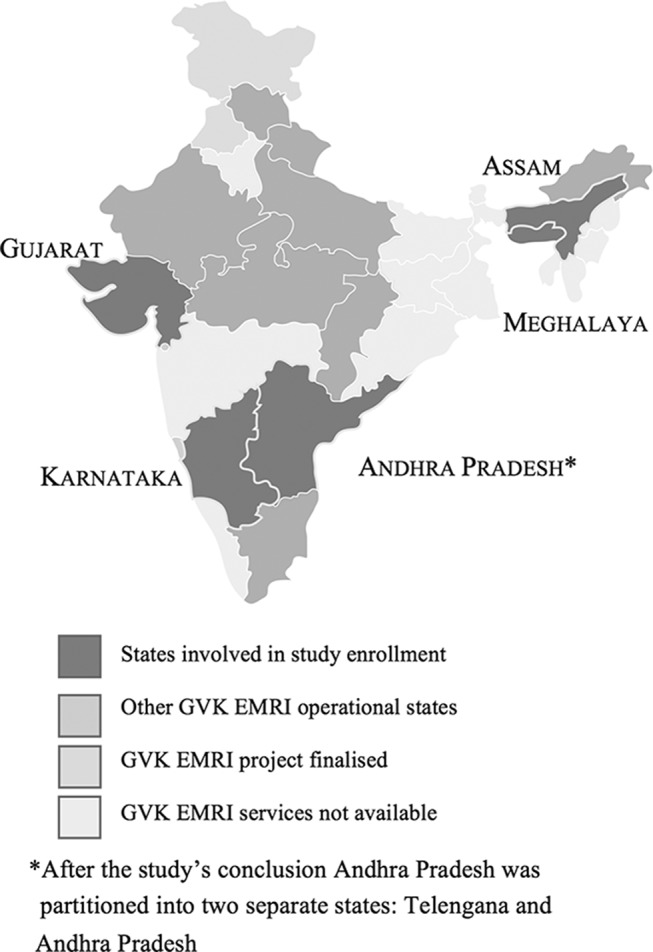

Over a 6-week period, from February to April 2014, research assistants enrolled a convenience sample of neonates born to women in their third trimester of pregnancy who called for GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute (GVK EMRI) ambulance transport for pregnancy-related complaints. Neonates were enrolled from one of five participating Indian states: Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat, Karnataka and Meghalaya (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Availability of GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute (EMRI) services and study enrolment by Indian state.

GVK EMRI

GVK EMRI, named after Gunupati Venkata Krishna, is a not-for-profit, public-private partnership that provides free ambulance transport and prehospital stabilisation care that can be accessed using a three-digit, toll-free phone number. Launched in 2005, GVK EMRI is currently the largest provider of emergency medical services (EMS) in India (and in the world), operating in 17 of 28 Indian states and union territories and representing a catchment population of 750 million people. Obstetric emergencies comprise the single largest category of GVK EMRI’s prehospital transports, with upwards of 30% of all calls being pregnancy-related, totalling 3.1 million calls for pregnancy-related complaints in 2014.11 This is in comparison to the US and European countries where maternal and pregnancy calls are often <1% of total.12

Call management, dispatch and online medical direction are provided by central state-based, emergency call centres that support a fleet of ambulances, strategically distributed to optimise response times. Individual ambulance providers are dispatched based on availability and distance to the patient. The majority of ambulances are staffed by both a driver and a single EMT. EMTs are trained to provide basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care, including resuscitation and administration of life-saving medications, with oversight from real-time physician-guided medical direction available by phone. EMTs scope of practice around obstetric, gynaecologic and neonatal care are driven by standard protocols (see online supplementary material 1). Patients are transported to the nearest appropriate public or private care facility unless they request an alternate facility.

bmjopen-2017-019937supp001.pdf (3.4MB, pdf)

Enrolment process

Patients were enrolled 6 days a week, Monday through Saturday, during daytime hours for 6 hours per day. Enrolment was limited to this time frame given constraints of research assistant availability, safety and cost. Any woman in her third trimester of pregnancy who called for a pregnancy-related complaint was eligible for enrolment. A call was considered ‘pregnancy-related’ if it was categorised by the dispatch officer as a call for ‘pregnancy’, ‘childbirth’, ‘miscarriage’ or ‘labour pains’. Exclusion criteria included calls for interfacility transfers, patients who were absent on EMT arrival and patients who refused care. Newborns of women callers were enrolled if born to a mother within 7 days of the initial call.

Data collection

EMTs collected demographic, historical and current clinical data related to both maternal and neonatal care during and after ambulance transport. This information was relayed and categorised by research assistants via telephone in real time.

Neonates were matched to maternal demographic, prenatal characteristics and prehospital care. Demographic data included geography, economic status (defined by maternal possession of the low-income government health insurance programme white ration card), prior maternal education and current employment. Social status was classified by maternal self-identified caste; lower social classes included ‘scheduled caste’ (lowest, most socially disadvantaged group), ‘scheduled tribe’ (socially and geographically disadvantaged) and ‘backward caste’ (intermediary group socially). ‘Other caste’ included refers to those with the highest social status.

Among the subset of neonates delivered either prior to ambulance arrival or in the prehospital setting (under the care of an EMT), direct neonatal clinical care data were also recorded. Newborn infant gestational age was determined by maternal report often based on last menstrual period.

Two separate telephone numbers, the mother’s and a friend’s or relative’s, were collected at the time of enrolment to facilitate patient follow-up. All patients who delivered prior to EMS arrival through 7 days after the dispatch call, were followed up by phone at 48 hours, 7 days and 42 days postpartum.13 The 42-day follow-up period was used to capture maternal mortality as well as young infant outcomes.

Per GVK EMRI’s standard protocol, all patients were verbally consented by responding EMTs for treatment, data collection and follow-up at the time of enrolment.

Data analysis

Initial patient data were recorded securely online using REDCap (Stanford University).14 All data analysis was conducted via SAS Enterprise Guide for Windows, V.4.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Both maternal and patient data were cleaned and de-identified for analyses. Descriptive demographic and maternal clinical data were provided as numbers and percentages where appropriate. In addition to descriptive data, main outcomes included medical interventions in the prehospital setting and mortality at each stage of follow-up. We were unable to differentiate stillbirths versus neonatal deaths that occurred on the day of delivery.

Wilcoxon rank sum and Χ2 tests were used to compare cases of early infant deaths to those that survived to 2, 7 and 42 days. Variables analysed included demography, items in the maternal prenatal and past medical history and in the medical care history in the prehospital setting and delivery characteristics.

A multivariate model was constructed using variables that were significant from the Χ2 tests. State was not included in initial multivariate models, although it was controlled for in iterative analysis given the variability in enrolment and proportional variability in early infant death from state to state. ORs and 95% CIs were used to assess the association of individual variables with infant death.

Results

A total of 1411 (83.8%) of the 1684 women enrolled gave birth to a total of 1431 newborns (including 40 twins, 2.8%) within 7 days of calling for ambulance services (table 1). This represents approximately 1.7% of all pregnancy-related calls to GVK EMRI across the five states during the study period.

Table 1.

Demographic and maternal health characteristics among neonates born to mothers using emergency medical services in five states in India, February–April 2014

| n=1431 | % | |

| Maternal demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| Median (IQR) | 23 | 21–26 |

| 15–19 | 70 | 4.9 |

| 20–24 | 809 | 56.5 |

| 25–29 | 434 | 30.3 |

| 30–34 | 92 | 6.4 |

| 35–39 | 23 | 1.6 |

| 40–44 | 3 | 0.2 |

| State | ||

| Andhra Pradesh | 381 | 26.6 |

| Assam | 201 | 14.0 |

| Gujarat | 477 | 33.3 |

| Karnataka | 342 | 23.9 |

| Meghalaya | 30 | 2.1 |

| Geographic location | ||

| Rural/tribal | 1323 | 92.5 |

| Urban | 108 | 7.5 |

| Social status* | ||

| Backward caste | 508 | 35.5 |

| Other caste | 284 | 19.8 |

| Scheduled caste | 254 | 17.7 |

| Scheduled tribe | 381 | 26.6 |

| Economic status† | ||

| Pink ration card | 422 | 29.5 |

| White ration card | 987 | 69.0 |

| Education level completed | ||

| None | 528 | 36.9 |

| Primary | 357 | 24.9 |

| Secondary | 381 | 26.6 |

| Intermediate | 81 | 5.7 |

| Graduate degree | 37 | 2.6 |

| Occupation | ||

| Homemaker | 1079 | 75.4 |

| Other | 352 | 24.6 |

| Medical history | ||

| Anaemia | 99 | 6.9 |

| Hypertension | 10 | 0.7 |

| Pulmonary disease | 4 | 0.3 |

| HIV | 2 | 0.1 |

| Antenatal care visits | ||

| 1–3 | 732 | 51.2 |

| >3 | 671 | 46.9 |

| ≥1 visit with a physician | 1111 | 77.6 |

| Iron supplementation | 1197 | 83.6 |

| Parity | ||

| Multiparous | 818 | 57.2 |

| Nulliparous | 613 | 42.8 |

| Age at first pregnancy‡ | ||

| Median (IQR) | 21 | 20–22 |

| 15–19 | 197 | 24.1 |

| 20–24 | 550 | 67.2 |

| 25–29 | 65 | 7.9 |

| 30–34 | 3 | 0.4 |

| Years since prior pregnancy‡ | ||

| ≤2 | 364 | 44.5 |

| 3 | 211 | 25.8 |

| ≥3 | 237 | 29.0 |

*Self-identified caste is used as a proxy for social status and in India and is often used in national population health level monitoring. Scheduled caste is the lowest, most socially disadvantaged group. ‘Scheduled tribe’ is also a disadvantaged group. ‘Backward caste’ is an intermediary group socially and ‘other caste’ includes all those who do not belong to the aforementioned group and have the highest social status.

†Economic status is defined by whether patients were dependent on the low-income government health insurance programme (white ration card).

‡Of multiparous mothers only (n=818).

Most neonates were born to mothers from rural or tribal areas (n=1323, 92.5%), lower economic status (n=987, 69.0%), lower social class (n=1143, 79.9%) and had less than a secondary education (n=885, 61.8%).

At the time of initial ambulance call, 82.5% (n=1180) of women were early or full term gestation (37–42 weeks), 97.2% (n=1391) reported contractions or abdominal pain, 31.0% (n=443) had rupture of membranes with contractions and 7.9% (n=113) had vaginal bleeding (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of neonates periemergency medical services transport in five states in India, February–April 2014

| n=1431 | % | |

| Prehospital characteristics | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) at transport | ||

| Median (IQR) | 39.7 | 38.4–40.0 |

| <32 | 28 | 2.0 |

| 32–36 | 164 | 11.5 |

| 37–42 | 1180 | 82.5 |

| >42 | 38 | 2.7 |

| Receiving hospital type | ||

| Government | 1181 | 82.5 |

| Private/paid | 187 | 13.1 |

| Trust/NGO | 50 | 3.5 |

| Distance from scene to facility (km) | 15 | 9–23 |

| Time from call to facility (min) | 65 | 50–84 |

| Presentation | ||

| Contractions | 1391 | 97.2 |

| Rupture of membranes | 443 | 31.0 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 113 | 7.9 |

| Abnormal maternal vital recorded | 301 | 22.1 |

| HR≥100 | 112 | 7.8 |

| SBP<90 | 16 | 1.2 |

| SBP≥140 and <160 or DBP≥90 and <110 | 192 | 13.4 |

| SBP≥160 or DBP≥110 | 20 | 1.4 |

| RR≥30 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Emergency medical technician actions | ||

| Left lateral positioning | 1364 | 95.3 |

| Oxygen provided | 331 | 23.1 |

| Intravenously placed | 165 | 11.5 |

| Delivery characteristics | ||

| When delivered | ||

| Prior to ambulance arrival | 37 | 2.6 |

| After ambulance arrival and prior to hospital admission | 45 | 3.1 |

| Within 48 hours | 1285 | 89.8 |

| Within 7 days | 64 | 4.5 |

| In-hospital | 1274 | 89.1 |

| Term (>37 weeks gestation) | 1223 | 85.5 |

| Vaginal | 1170 | 81.8 |

| Twin | 40 | 2.80 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; NGO, non-governmental oragnisation; RR, respiration rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Abnormal prehospital vital signs (pulse rate>99, respiratory rate>29, systolic blood pressure<90 or >140 or diastolic blood pressure>90) were documented in 22.1% (n=301) of women. Of those women with tachycardia (n=112), 89.3% (n=100) were placed in the left lateral position and 10.7% (n=12) received intravenous fluids. Among those women with documented hypotension (n=16), 75.0% (n=12) were placed in the left lateral position and 37.5% (n=6) received intravenous fluids. In sum, four women died during this study, and all within 48 hours after hospital arrival (for further discussion of this high-risk group see reference 13).

Prior to hospital admission, 82 (5.7%) neonates were delivered from 80 distinct mothers. Thirty-seven delivered prior to ambulance arrival. EMTs assisted in the delivery of 45 neonates, either on scene (where the ambulance picked up the patient), during transport or immediately on hospital arrival. Another 1349 (94.3%) deliveries occurred after EMS transport, with the majority (n=1285, 89.8%) occurring within 2 days of EMS dispatch. Of the deliveries that followed EMS transport, 1274 (94.4%) occurred in the hospital and another 74 (5.5%) followed hospital discharge.

The median distance from the scene to the hospital was 15 km (IQR 9–23). The median time from initial call to hospital arrival was 65 min (IQR 50–84).

The overall follow-up rates at 2, 7 and 42 days were 99.8%, 99.3% and 94.1%, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Follow-up and cumulative mortality stratified by Indian state, February–April 2014

| Andhra Pradesh | Assam | Gujarat | Karnataka | Meghalaya | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| N | 381 | 201 | 477 | 342 | 30 | |||||

| Follow-up | ||||||||||

| 2 Days | 379 | 99.5 | 201 | 100 | 477 | 100 | 341 | 99.7 | 30 | 100 |

| 7 Days | 378 | 99.2 | 199 | 99.0 | 475 | 99.6 | 339 | 99.1 | 30 | 100 |

| 42 Days | 359 | 94.2 | 180 | 89.6 | 444 | 93.1 | 334 | 97.7 | 30 | 100 |

| Cumulative mortality | ||||||||||

| 2 Days | 13 | 3.4 | 10 | 5.0 | 21 | 4.4 | 13 | 3.8 | 5 | 16.7 |

| 7 Days | 14 | 3.7 | 12 | 6.0 | 31 | 6.5 | 14 | 4.1 | 5 | 16.7 |

| 42 Days | 14 | 3.9 | 13 | 7.2 | 37 | 8.3 | 14 | 4.2 | 6 | 20.0 |

In sum, 62 neonates died by day 2, 76 neonates died by day 7 and a total of 84 young infants perished by day 42 (table 4). Cumulative mortality rates were 53 and 62 per 1000 births at 7 and 42 days follow-up, respectively. The calculated PMR was 53 deaths per 1000 births. There was variation in state PMR with the highest 7-day mortality rate in the state of Meghalaya (166 per 1000, P value=0.019). PMRs in Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat and Karnataka were 37, 60, 65 and 41 per 1000, respectively. Other demographic indicators, including economic, social (caste status), education or occupational status of the mother were not significantly related to mortality in univariate analysis.

Table 4.

Characteristics and factors associated with perinatal mortality in five states in India, February–April 2014

| Alive | Dead | P value | |||

| n=1345 | % | n=76 | % | ||

| Maternal demographic characteristics | |||||

| Rural or tribal geography | 1243 | 92.4 | 72 | 94.7 | 0.652 |

| State | |||||

| Andhra Pradesh | 364 | 27.1 | 14 | 18.4 | 0.972 |

| Assam | 187 | 13.9 | 12 | 15.8 | 0.645 |

| Gujarat | 444 | 33.0 | 31 | 40.8 | 0.162 |

| Karnataka | 325 | 24.2 | 14 | 18.4 | 0.253 |

| Meghalaya | 25 | 1.9 | 5 | 6.6 | 0.019 |

| Social status | |||||

| Other caste | 270 | 20.1 | 12 | 15.8 | 0.356 |

| Non-other caste | 1071 | 79.6 | 64 | 84.2 | |

| Economic status | |||||

| Pink ration card | 396 | 29.4 | 24 | 31.6 | 0.639 |

| White ration card | 930 | 69.1 | 50 | 65.8 | |

| Education level | |||||

| No prior schooling | 489 | 36.4 | 32 | 42.1 | 0.332 |

| Attended school | 811 | 60.3 | 42 | 55.3 | |

| Homemaker | 1014 | 75.4 | 59 | 77.6 | 0.658 |

| ≥2 years since prior delivery | 423 | 31.4 | 23 | 30.3 | 0.802 |

| Maternal prenatal characteristics | |||||

| Prenatal iron supplementation | 1129 | 83.9 | 60 | 78.9 | 0.248 |

| ≥1 visit with a physician | 1046 | 77.8 | 57 | 75.0 | 0.532 |

| <4 Antenatal care visits | 677 | 50.3 | 49 | 64.5 | 0.019 |

| Current maternal and neonatal care | |||||

| Any abnormal maternal vital sign | 264 | 19.6 | 27 | 35.5 | 0.019 |

| Caesarean section | 107 | 8.0 | 13 | 17.1 | 0.005 |

| Delivery prior to hospital admission | 73 | 5.4 | 6 | 7.9 | 0.361 |

| In-hospital | 1197 | 89.0 | 68 | 89.5 | 0.911 |

| Intravenously placed in mother | 148 | 11.0 | 13 | 17.1 | 0.103 |

| Intravenous fluids given to mother | 56 | 4.2 | 9 | 11.8 | 0.018 |

| Maternal tachycardia (heart rate≥100) | 102 | 7.6 | 10 | 13.2 | 0.081 |

| Left lateral position during transport | 1287 | 95.7 | 69 | 90.8 | 0.047 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 62 | 4.6 | 8 | 10.5 | 0.021 |

| Preterm (<37 weeks) | 167 | 12.4 | 18 | 23.7 | 0.005 |

| Twin | 33 | 2.5 | 7 | 9.2 | 0.001 |

Numbers in bold are statistically signficant at p value <0.05.

Univariate analysis among all mothers identified the following maternal risk factors for elevated neonatal mortality at 7 days: less than four antenatal care (ANC) visits (P value=0.019), abnormal vital signs (P value=0.049), maternal intravenous placement (P value=0.007) and intravenous fluids given (P value=0.018) and mother not placed in left lateral position during transport (P value=0.047). Of those infants delivered in the presence of prehospital care providers, the cumulative mortality rate at 42 days was 122 per 1000 (n=5) with four infants lost to follow-up.

The association between maternal and infant characteristics and death at 7 and 42 days follow-up was also assessed through multivariate logistic regression (table 5). At 42 days follow-up, preterm birth (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.67 to 5.00) and twin deliveries (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.10 to 7.15) were the strongest predictors of mortality. Other maternal risk factors raising the likelihood of young infant death included not being placed in the left lateral position en route to the hospital (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.06 to 5.61), heart rate >100 (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.13 to 4.35) or having a caesarean section delivery (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.23). The risk of death was nearly twofold higher for young infants born to mothers who went to fewer than four ANC visits (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.14 to 3.14).

Table 5.

Predictors of young infant mortality at 7 and 42 days follow-up by multivariate logistic regression models

| 7 Days | 42 Days | |||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Prematurity (<37 weeks) | 2.21 | 1.19 to 4.09 | 2.89 | 1.67 to 5.00 |

| Twin delivery | 3.87 | 1.56 to 9.64 | 2.80 | 1.10 to 7.15 |

| Caesarean section | 1.93 | 0.92 to 4.03 | 2.21 | 1.15 to 4.23 |

| <4 antenatal care visits | 1.76 | 1.02 to 3.02 | 1.89 | 1.14 to 3.14 |

| Not placed in left lateral position* | 1.67 | 0.62 to 4.46 | 2.44 | 1.06 to 5.61 |

| Maternal heart rate ≥100* | 1.57 | 0.70 to 3.52 | 2.21 | 1.13 to 4.35 |

*When controlled by state these variables were no longer statistically significant.

Controlling for geographic (state-to-state) variability in overall PMR led to some changes in the multivariate regression model for 42-day mortality. Prematurity (OR 3.08, 95% CI 1.77 to 5.35), twin delivery (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.07 to 7.23), fewer than four ANC visits (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.03 to 5.89) and caesarean section delivery (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 4.45) continued to be independent predictors of overall young infant mortality, while maternal tachycardia (OR 1.76, 95% CI 0.86 to 3.62) and maternal positioning (OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.87 to 4.85) were no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

Reducing the equity gap

Elevated neonatal mortality has been shown globally to be associated with various forms of marginalisation, including poverty, low maternal education and low social standing.15 Previous programmes to reduce neonatal mortality have focused on reducing the equity gap—reaching women and newborn infants in greatest need and those with limited access to formal healthcare services.16–18 This prospective study suggests EMS plays an important, but underappreciated role in reaching women from a lower socioeconomic strata and adds to prior data supporting the role of centralised EMS services in maternal and neonatal health policy.10 Prehospital interventions and rapid transport when coupled with current data on known community and hospital-based risks has the potential to lead to development of interventions aimed at further reducing neonatal deaths.19–21

Ambulance services cared for a population—93% from lower social or economic strata— that historically has had less timely access to formal medical services. EMTs performed essential prehospital services, including assisting with the delivery of newborns in the field and during transport to the hospital. In 94% of all transports, EMTs connected women and neonates to health facilities offering obstetric care in <2 hours.

The absence of an association between mortality and social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status or education level, was unexpected. However, the overwhelmingly high number of neonates from lower socioeconomic classes in our study cohort decreased our ability to detect the impact of these demographic characteristics on mortality. Furthermore, the impact of socioeconomic status on neonatal mortality may be very closely linked to the lack of access to care customary to these populations. In our study, where the majority of mothers were from disadvantaged backgrounds, this link did not exist. EMS may serve to overcome many factors that have traditionally been thought to limit healthcare access for poor and marginalised populations; thus, access to care was broadly provided for all populations by the responding EMTs and subsequent ambulance transport. This suggests that delivery of EMS may be an important means to achieve greater equity in healthcare delivery.

Quality of prehospital care

Deficits in the quality of India’s prehospital care of pregnant women persist. Maternal haemodynamic instability has significant risks for neonatal health,22 23 and subsequent maternal resuscitation, whether through positioning or administration of fluids, has been shown to increase cardiac output and stroke volume—effectively improving maternal and, by-proxy, neonatal haemodynamics, even among those women who deliver after hospital arrival.24 25 Continued training aimed at EMT recognition of high-risk patients and treatment with simple interventions based on vital signs abnormalities is imperative. Ongoing quality assurance and training efforts are now aimed at increasing EMT recognition of high-risk patients, rates of fluid resuscitation and proper positioning during prehospital maternal resuscitation. Lastly, prehospital interventions whether through patient positioning, fluid resuscitation or timely diversion of high-risk patients to facilities with trained providers suggestive of a higher level of care all serve to affect births that occur after delivery.

Helping a high-risk population

In low-income and middle-income countries, most perinatal deaths occur at home.26 Several studies suggest that the reported PMR for all of India of 28 per 1000 births is also an underestimate given the difficulty in capturing stillbirths occurring at home.8 27 Estimates suggest that transitioning to institutional deliveries with a skilled birth attendant in lieu of traditional home deliveries could prevent over 5 00 000 stillbirths and 1.3 million annual neonatal deaths by 2020.28 29 Yet, even with transport to healthcare facilities, the estimated PMR of 53 deaths per 1000 births is nearly double the reported national average. While PMR varied considerably by state, all, except for Karnataka, had reported PMRs greater than previously reported averages for the year 2013.7 Comparatively, the PMR in our study ranged from 37 to 167 per 1000 in the five states, while published PMRs for Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat and Karnataka ranged from 24 to 30 per 1000.

The high PMR is likely multifactorial. Prematurity (based on maternal report of gestational age) was found to be one of the strongest predictors of death. This relationship is consistent with global data identifying this as the number one cause of neonatal death.30 While the proportion of prematurity in this study was similar to reported rates of India as a whole, the proportion of infants born premature who died within the first 7 days of life was higher than previous hospital-based studies.31 Moreover, many deaths in preterm infants occur early in the neonatal period, and rapid intervention, made possible through transport under the care of an EMT to healthcare facilities with the capabilities to provide neonatal intensive care is critically important for survival.

The natural twinning rate in the study was 14.0 per 1000 births, almost double the estimated 7.2 per 1000 births reported across India.32 Twin births were a significant predictor of death in this study (OR 2.8) and thus another important factor in the increased PMR.

The relationship between initial maternal haemodynamic instability and mortality of their infants suggests that the level of acuity of our maternal cohort was high. Women may not recognise the need to seek emergent care and are calling EMS only when they are in a very critical condition.

Finally, almost half (47.4%) of women enrolled in our study attended less than the recommended four ANC visits, a factor which proved to also be an important predictor of young infant mortality in this study. Population-based data for India shows similar ANC visitation rates at around 51%.1 The risk associated with a lack of ANC visits supports consensus-based recommendations emphasising the importance of family planning and ANC, as women in this study may have had complications that went unrecognised in the perinatal period and that presented as emergencies necessitating the use of EMS.

Notably, the PMR associated with this cohort of patients was significantly higher than known state averages and associated with risk factors that, when addressed in future efforts, will be important in reducing neonatal mortality. In this study, however, we were unable to link records from prehospital care with those for hospital-based care, and thus we cannot comment on the relationship between mortality and variability in post-transport facility-based care in India, including treatments, disease course and cause of death in hospital.

Additionally, we were unable to differentiate stillbirths versus deaths that occurred on day 1 of life and while this may serve to limit our recommendations we believe emergency response services have the potential to improve data quality while at the same time promote equity in access to healthcare services, and improve perinatal survival in India no matter the cause. The elevated PMR in this large patient cohort is reflective of the high-risk nature of this population and the need for further attention to coverage of these services, provision of high-quality tailored interventions and focused investigations to inform continuous improvement in EMS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following for support in data collection and quality: Rajini Danthala, Aruna Gimkala, Divya Patel, Royal Uddin Ahmed, Steffy Christian, Eranna Gowda, Chandrashekhraswamy Kendadmath, Marada Lakshmana Rao, Rupjoy Maibangsa, Shylaja Muniyappa, Isberth Tham, Sahyadri Venkateshappa and Aditya Mantha.

Footnotes

Contributors: MCS, EAP, GVRR and SVM contributed to the study design, implementation, data analysis and manuscript production. CBB and JAN contributed to data analysis and manuscript production. GD contributed to manuscript production. CBB, MCS and SVM accept full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University (IRB#18185) and the Ethics and Research Committee at GVK EMRI.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.38n0n.

References

- 1. UNICEF. UNICEF Data: monitoring the situation of children and women. http://data.unicef.org/child-mortality/neonatal.html (accessed 24 Jun 2016).

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). The partnership for maternal, newborn and child health. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/press_materials/fs/fs_newborndealth_illness/en/ (accessed 4 Feb 2016).

- 3. NIMS, ICMR and UNICEF. Infant and child mortality in india: levels, trends and determinants. New Delhi, India: NIMS, ICMR and UNICEF; 2012. http://unicef.in/CkEditor/ck_Uploaded_Images/img_1365.pdf (accessed 8 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiffman J. Issue attention in global health: the case of newborn survival. Lancet 2010;375:2045–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60710-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1969–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, et al. Every Newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet 2014;384:189–205. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System (SRS) statistical report 2012. New Delhi: Registrar General of India; 2013. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Report_2012/2_At_a_glance_2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sankar MJ, Neogi SB, Sharma J, et al. State of newborn health in India. J Perinatol 2016;36:S3–S8. 10.1038/jp.2016.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, et al. Lancet maternal survival series steering group. Going to scale with professional skilled care. Lancet 2006;368:1377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Babiarz KS, Mahadevan SV, Divi N, et al. Ambulance service associated with reduced probabilities of neonatal and infant mortality in two Indian States. Health Aff 2016;35:1774–82. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. GVK Emergency Management Research Institute. National Daily Report. 2014.

- 12. NEMSIS. V2 911 Call Complaint vs. EMS Provider Findings Dashboard. 2016. https://nemsis.org/view-reports/public-reports/version-2-public-dashboards/v2-911-call-complaint-vs-ems-provider-findings-dashboard/ (accessed 20 Dec 2017).

- 13. Strehlow MC, Newberry JA, Bills CB, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of women using emergency medical services for third-trimester pregnancy-related problems in India: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2016;6:7 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matthews Z, Channon A, Neal S, et al. Examining the ‘urban advantage’ in maternal health care in developing countries. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000327 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Victora CG, Barros AJ, Axelson H, et al. How changes in coverage affect equity in maternal and child health interventions in 35 Countdown to 2015 countries: an analysis of national surveys. Lancet 2012;380:1149–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61427-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mittal K, Gupta V, Khanna P, et al. Evaluation of Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) algorithm for diagnosis and referral in under-five children. Indian J Pediatr 2014;81:797–9. 10.1007/s12098-013-1225-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lassi ZS, Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;11:CD007754 10.1002/14651858.CD007754.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? The Lancet 2005;365:977–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, et al. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet 2005;365:1087–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74233-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martines J, Paul VK, Bhutta ZA, et al. Neonatal survival: a call for action. The Lancet 2005;365:1189–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71882-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grivell RM, Alfirevic Z, Gyte GML, et al. Antenatal cardiotocography for fetal assessment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;181 10.1002/14651858.CD007863.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Devane D, Lalor JG, Daly S, et al. Cardiotocography versus intermittent auscultation of fetal heart on admission to labour ward for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fujitani S, Baldisseri MR. Hemodynamic assessment in a pregnant and peripartum patient. Crit Care Med 2005;33 S354–S361. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000183156.73560.0C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clark SL, Cotton DB, Pivarnik JM, et al. Position change and central hemodynamic profile during normal third-trimester pregnancy and post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:883–7. 10.1016/S0002-9378(11)90534-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:69–79. 10.1093/heapol/czh009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. SRS Statistical report 2012. 2012. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Reports_2012.html (accessed 22 Jan 2016).

- 28. Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 2006;368:1284–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? The Lancet 2014;384:347–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, et al. Every Newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. The Lancet 2014;384:189–205. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rather GN, Jan M, Rafiq W, et al. Morbidity and mortality pattern in late preterm infants at a tertiary care hospital in Jammu & Kashmir, Northern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:SC01–SC04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smits J, Monden C. Twinning across the developing World. PLoS One 2011;6:e2523 10.1371/journal.pone.0025239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019937supp001.pdf (3.4MB, pdf)