Abstract

Objective

To evaluate fasting plasma glucose (FPG) as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) among Mexican adolescents using International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Level-three medical institution in Mexico City.

Participants

The study population comprised 1061 adolescent women aged 12–19 years with singleton pregnancies, who underwent a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 11 and 35 weeks of gestation.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively), and positive and negative likelihood ratios LR (+) and LR (−), respectively) with 95% CIs for selected FPG cut-off values were compared. Secondary measures were perinatal outcomes in women with and without GDM.

Results

GDM was present in 71 women (6.7%, 95% CI 5.3% to 8.4%). The performances of FPG at thresholds of ≥80 (4.5 mmol/L), 85 (4.7 mmol/L) and 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) were as follow (95% CI): Sn: 97% (89% to 99%), 94% (86% to 97%) and 91% (82% to 95%); Sp: 50% (47% to 53%), 79% (76% to 81%) and 97% (95% to 97%); PPV: 12% (9% to 15%), 23% (18% to 28%) and 64% (54% to 73%); NPV: 99% (98.5% to 99.9%) for all three cut-offs; LR (+): 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1), 4.3 (3.8 to 5.0) and 26.7 (18.8 to 37.1) and LR (−): 0.06 (0.02 to 0.23), 0.07 (0.03 to 0.19) and 0.09 (0.04 to 0.19), respectively. No significant differences in perinatal outcomes were found between adolescents with and without GDM.

Conclusions

An FPG cut-off of ≥90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) is ideal for GDM screening in Mexican adolescent women. An FPG threshold of 90 mg/dL would miss 6 (8.5%) women with GDM, pick up 34 (3.4%) women without GDM and avoid 962 (90.7%) OGTTs.

Keywords: gestational diabetes, IADPSG, hyperglycaemia, pregnancy, adolescent

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A fasting glucose cut-off of ≥90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) is ideal for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) screening among Mexican adolescent women.

This is the first study in Mexico and Latin America addressing the prevalence of GDM in adolescent women using International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria.

The study was retrospective; the findings are only applicable to Mexican, and potentially, Latin women.

The diagnostic validity of the test was not confirmed in a second independent population.

The sample size available to compare perinatal outcomes was limited.

Introduction

Around 16 million women aged 15‒19 years give birth each year, accounting for approximately 11% of all births worldwide. In total, 95% of these births occur in low/middle-income countries; 18% in Latin America and the Caribbean and more than 50% in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Latin women (including Mexican women) are considered a high-risk population for diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).2

GDM refers to diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.2 Although the prevalence of GDM is generally lower in adolescent populations, a recently published guideline concerning adolescent pregnancy recommended GDM testing for all pregnant adolescent women, similar to recommendations for adult women.3

Previous studies reported GDM prevalence rates of 1.7% among North American adolescent women4 and 0.97% among Mexican adolescent women5; both studies diagnosed GDM using Carpenter and Coustan criteria.6 However, reports about the prevalence of GDM in adolescents diagnosed using the new International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria are limited. The present authors previously reported a prevalence of GDM among adult Mexican women of 30.3% using IADPSG criteria; a figure threefold higher than that obtained using the previous American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria (valid until 2010).7

In Mexico, pregnant adolescent women have a lower prevalence of overweight and obesity than the general pregnant population. Additionally, most pregnant Mexican adolescent women are primigravid. In part, these characteristics contribute to the low prevalence of GDM in this population.8 9 However, most pregnant Mexican adolescent women have lower socioeconomic status than adult women.8 Lower socioeconomic status has been associated with a higher frequency of consumption of unhealthy foods (eg, soft drinks10), which are associated with increased risk of GDM among Mexican women.

Currently, GDM screening and diagnosis in adolescent women is controversial because of the low prevalence of GDM in this population and non-universal strategies for diagnosing GDM. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study revealed significant associations between adverse perinatal outcomes and fasting, 1 and 2-hour glucose values during a 2-hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).11 Following these results, the IADPSG recommended new criteria for the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycaemia during pregnancy.12 The new glucose thresholds corresponded to 1.75 times the estimated odds for neonatal birth weight >90th percentile, cord C-peptide >90 th percentile and body fat percentage >90 th percentile.12 Use of IADPSG criteria is supported by various international associations, including the ADA,2 Endocrine Society,13WHO14 and International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).15 However, other organisations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHHD), recommend that healthcare providers continue to use a two-step approach to screen and diagnose GDM.16 17 They argue that there is no evidence to support clinically significant improvements in maternal or newborn outcomes after using IADPSG criteria to diagnose GDM, and that following these criteria leads to a significant increase in healthcare costs.16 17 All of the above-mentioned organisations recommend universal screening for GDM using a one or two-step strategy, and none have specific recommendations regarding GDM screening for adolescent women.

In contrast, recent guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence on diabetes in pregnancy recommend 2 hour 75 g OGTT at 24–28 gestational weeks to test for GDM in women with risk factors. These guidelines also propose a diagnosis of GDM if a 2-hour 75 g OGTT shows women have either a fasting glucose level ≥100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or a 2-hour glucose level ≥140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).18 In accordance with this guideline, adolescent women should be tested for GDM if they have body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, a previous baby with macrosomia weighing ≥4.5 kg or with gestational diabetes, a first-degree relative with diabetes or an ethnic family origin with a high prevalence of diabetes.

Agarwal et al 19 suggested fasting plasma glucose (FPG) can be used to decide if an OGTT is needed or not. This would ease the burden on laboratories and save resources, as the IADPSG recommendation that every pregnant woman undergoes a 2-hour 75 g OGTT is too demanding.19 A systematic review and meta-analysis of GDM screening tests concluded that glucose challenge tests and FPG levels at 24 gestational weeks are useful for identifying women who do not have GDM.20 However, no studies have analysed the use of fasting glucose for screening GDM in adolescent women.

This study aimed to evaluate the usefulness of fasting glucose for GDM screening among Mexican adolescent women using IADPSG diagnostic criteria. Secondary goals were to report the prevalence of GDM and perinatal outcomes in adolescent women with and without GDM.

Methods

Study design and participants

A retrospective cohort study was conducted. The study population was adolescents who received prenatal care at Instituto Nacional de Perinatología (INPer) in Mexico City, from 1 June 2011 to 30 June 2014. INPer is a reference centre that attends to high-risk pregnancies, including adolescent women. Nearly 4000 births are attended at INPer every year. This study was approved by the INPer Internal Review Board (Register number 212250-42081). Written informed consent from participants is not required by the Internal Review Board for retrospective studies. The inclusion criteria were women who were aged 12–19 years, had a singleton pregnancy, had received a 2-hour 75 g OGTT administered at 11–35 weeks of gestation and had delivered at INPer. The exclusion criterion was women with any pathology, including any type of pregestational diabetes, lupus, heart disease, substance abuse, hypothyroidism, epilepsy, leukaemia, bulimia, anorexia, depressive disorder, autoimmune cirrhosis, asthma or multiple sclerosis. Adolescent women with pregestational diabetes (type 1 or 2) or GDM were referred to INPer from level-one or level-two attention centres, and OGTT was avoided in this population.

Procedure

First, adolescent women who delivered during the study period were identified from the electronic register of births. Next, non-electronic clinical records were reviewed to check if these women had received an OGTT, and in which week of gestation the test was performed. Pregnant adolescent women with an OGTT between 11 and 35 weeks of gestation were selected; if the inclusion criteria were fulfilled, their maternal and neonatal clinical records were requested to obtain data for analysis. Glucose was measured using the Vitros DT60 II chemistry system (OrthoClinical Diagnostics, Tilburg, the Netherlands), which has a sensitivity of 20 mg/dL (1.11 mmol/L) and a coefficient of variation of 1.4%–1.8%, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The laboratory fulfils the official Mexican norm (NOM-007-SSA3-2011) for the organisation and functioning of clinical laboratories in Mexico and is certified by the Global Certification Bureau for quality management systems in concordance with the International Standards Organisation 9001:2015 norm.

Gestational age was calculated from the last menstrual period. If women were unaware of when their last menstrual period was or if the date was not reliable, the first trimester ultrasound measurement was used. At INPer, GDM is diagnosed based on the observation of two or more abnormal values during a 2-hour 75 g OGTT: fasting ≥95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L), 1 hour≥180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L) and 2 hours≥155 mg/dL (8.6 mmol/L), according to recommendations from the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus.21 A single abnormal value was not considered sufficient for GDM diagnosis, and women who showed one value did not receive GDM-specific treatment. Women with two or more abnormal glucose values during OGTT received medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and subsequent evaluation of glycaemic control at 2–4 week intervals. For women who did not achieve glycaemic control with MNT, metformin was added at doses of 1500–2550 mg and/or insulin therapy (0.3–1.0 U/kg of body weight) to achieve goals for capillary glucose (self-monitoring): fasting <95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L) and 1 hour postprandial <140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).

Study variables

Fasting glucose was determined as part of the 2-hour 75 g OGTT. Cut-off values were established using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and Youden’s index. Glucose values obtained during the OGTTs were reanalysed according to IADPSG criteria, and GDM diagnosis was defined as one or more abnormal glucose value: fasting ≥92 mg/dL (5.1 mmol/L), 1 hour≥180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L) and 2 hours≥153 mg/dL (8.5 mmol/L).12

Additionally, perinatal outcomes were compared between women with and without GDM. This analysis only included GDM women without treatment. Large for gestational age was defined as a birth weight above the 90th percentile for sex and gestational age for Mexican people,22 and small for gestational age as a birth weight below the 10th percentile for sex and gestational age for Mexican people.22 Preeclampsia was defined as a blood pressure of ≥140/90 mm Hg and proteinuria >300 mg/24 hours. In the absence of proteinuria, the diagnosis of preeclampsia was based on a blood pressure of ≥140/90 mm Hg and one or more severity criteria: thrombocytopaenia, abnormal liver function, recent development of renal failure, pulmonary oedema or brain or visual disturbances. Gestational hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg after 20 gestational weeks in the absence of proteinuria and severity criteria. Intrauterine growth restriction was defined as the presence of an estimated fetal weight below the third percentile. Polyhydramnios was defined by an amniotic fluid index of >18 cm. Preterm birth was defined as birth after 20 and before 37 weeks of gestation. Maternal overweight was defined as a BMI for age greater than a+1 z-score, and obesity as a BMI for age greater than a+2 z-score, based on WHO references.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using recommendations for sample size estimation in diagnostic test studies. To find a 90% fasting glucose sensitivity for GDM screening, considering a prevalence of GDM of 6% and a maximum marginal error of 15% with a 95% CI, a sample size of 345 participants was required. However, all adolescent pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria during the study period were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.15 was used for the statistical analyses. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD and categorical variables as frequencies and proportions. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare continuous variables according to the variable distribution. Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were used to evaluate differences in proportions. Statistical significance was considered as p≤0.05. Contingency tables were determined to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio with 95% CIs, using different cut-off values based on the ROC curve and Youden’s index. The difference in the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes between adolescents with and without GDM was determined by calculating the OR with a 95% CI.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study.

Results

During the study period, there were 11 618 births at the study institution, 2122 of which occurred in adolescent women. In total, 1315 pregnant adolescent women had received a 2-hour 75 g OGTT. Of these women, 1061 met the inclusion criteria; 254 were excluded because of incomplete clinical records (n=105), twin pregnancies (n=13), incomplete OGTT (n=11), pregestational diabetes (n=2) or some additional pathology (n=123).

Most adolescent women who did not receive an OGTT received attention for hospitalisation or delivery for various reasons including: preterm labour, premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia and labour in active phase. During the study period, 32 pregnant adolescent women were referred to INPer with a previous diagnosis of some type of diabetes and had not received an OGTT; 19 with pregestational diabetes (8 with type 1 diabetes, 9 with type 2 diabetes) and 13 with GDM.

Seventy-one women were diagnosed with GDM, corresponding to a prevalence rate of 6.7% (95% CI 5.3% to 8.4%). Baseline data for adolescents with and without GDM collected on study enrolment are shown in table 1. Adolescents with GDM had higher weight and BMI than adolescents without GDM. The prevalence of obesity was higher among GDM women compared with those without GDM (P=0.001). Among the 71 adolescents with GDM diagnosed according to IADPSG criteria, the frequencies of abnormal glucose values during the 2-hour 75 g OGTT were: fasting, 64 (90.1%), 1 hour, 5 (7.0%) and 2 hours 7 (9.9%). Only one adolescent had three abnormal glucose values, and three adolescents had two abnormal glucose values.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adolescent women at study admission (n=1061)

| Characteristics | Total adolescents n=1061 |

Adolescents without GDM n=990 |

Adolescents with GDM n=71 |

P values* |

| Age (years) | 16.1±1.6 | 16.1±1.5 | 16.2±1.6 | 0.51 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.1±10.0 | 58.7±9.8 | 63.9±11.5 | 0.0001 |

| Height (m) | 1.56±0.05 | 1.56±0.05 | 1.56±0.05 | 0.69 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.3±3.6 | 24.1±3.5 | 26.2±4.1 | 0.0001 |

| Gestational age at 2 hours 75 g OGTT (weeks) | 25.0±4.4 | 24.1±3.5 | 26.1±4.1 | 0.008 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ||||

| Fasting | 80.2±7.3 | 79.2±6.2 | 94.4±6.2 | 0.0001 |

| 1 hour | 105.2±25.7 | 103.6±24.6 | 127.9±29.5 | 0.0001 |

| 2 hours | 97.9±19.4 | 96.6±18.4 | 114±24.4 | 0.0001 |

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| 1 | 923 (86.9) | 865 (87.3) | 58 (81.7) | 0.08 |

| 2 | 121 (11.4) | 110 (11.1) | 11 (15.5) | 0.17 |

| 3 or more | 18 (1.7) | 16 (1.6) | 2 (2.8) | 0.61 |

| Normal weight | 582 (55.6) | 559 (57.3) | 23 (32.4) | 0.001 |

| Overweight | 357 (34.1) | 324 (33.2) | 33 (46.5) | 0.01 |

| Obesity | 92 (8.8) | 77 (7.9) | 15 (21.1) | 0.001 |

| First-degree relative with type 2 diabetes | 157 (14.8) | 140 (14.1) | 17 (23.9) | 0.0.2 |

Values expressed as mean±SD deviation or frequency (percentage).

*Student’s t-test or χ2 test.

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

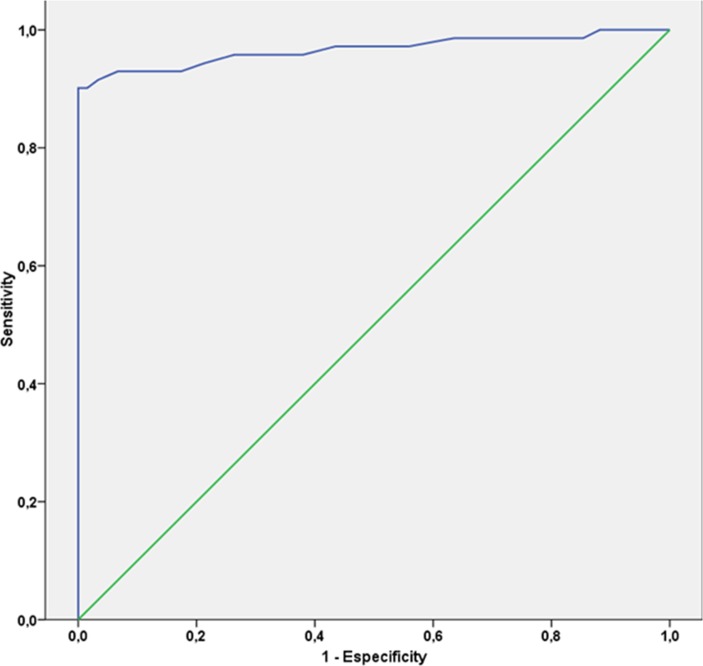

Figure 1 shows the ROC curve. The area under the curve was 0.96 (95% CI 0.93 to 0.99) (p=0.0001). Table 2 shows the results of the characterisation of the five fasting glucose cut-off values for GDM screening: 75, 80, 85, 90 and 92 mg/dL (4.2, 4.5, 4.7, 5.0 and 5.1 mmol/L, respectively). These cut-off values for fasting glucose were chosen based on Youden’s index and rounded up to the nearest integer (mg/dL). The best cut-off for fasting glucose according to Youden’s index was 90 mg/dL. Using a cut-off of 85 mg/dL (4.72 mmol/L), a total of 279 (26.3%) OGTTs would be necessary, whereas only 99 (9.3%) would be required with a cut-off of 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve shows an area under the curve of 0.96.

Table 2.

Gestational diabetes mellitus screening capacity among Mexican adolescents at different fasting glucose cut-off values

| Fasting glucose cut-off | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | LR (+) (95% CI) |

LR (−) (95% CI) |

OGTT |

| 75 mg/dL (4.2 mmol/L) | 98.5 (92 to 99) |

22.4 (20 to 25) |

7.9 (6 to 10) |

99.6 (97 to 99.9) |

1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) |

0.06 (0.01 to 0.46) |

838 (79%) |

| 80 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) | 97 (89 to 99) |

50.1 (47 to 53) |

11.6 (9 to 15) |

99.6 (98.5 to 99.9) |

1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) |

0.06 (0.02 to 0.23) |

563 (53.1%) |

| 85 mg/dL (4.7 mmol/L) | 94 (86 to 97) |

78.6 (76 to 81) |

22.9 (18 to 28) |

99.5 (98 to 99.8) |

4.3 (3.8 to 5.0) |

0.07 (0.03 to 0.19) |

279 (26.3%) |

| 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) | 91 (82 to 95) |

96.6 (95 to 97) |

64.2 (54 to 73) |

99.4 (98.6to 99.7) |

26.7 (18.8 to 37) |

0.09 (0.04 to 0.19) |

99 (9.3%) |

| 92 mg/dL (5.1 mmol/L) | 88.4 (78 to 94) |

99.9 (99 to 100) |

99.2 (91 to 99) |

99.2 (98 to 99) |

884 (123 to 6231) |

0.12 (0.06 to 0.22) |

64 (6%) |

LR, likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PPV, predictive positive value.

There were no differences in perinatal outcomes among Mexican adolescent women with GDM without treatment and those without GDM (table 3). However, there was a higher incidence of neonates that were small for gestational age among adolescents without GDM. Four women with GDM that received specific GDM treatment were excluded from this analysis; three with MNT and one with MNT plus metformin.

Table 3.

Risk of adverse perinatal outcomes among Mexican adolescent women with gestational diabetes mellitus* without treatment

| Adverse perinatal outcomes | Total n=1057 | Without GDM n=990 n (%) | With GDM n=67 n (%) | ORs (95% CI) | P value |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 36 (3.4) | 35 (3.5) | 1 (1.5) | 0.41 (0.06 to 3.1) | 0.37 |

| Polyhydramnios | 13 (1.2) | 12 (1.2) | 1 (1.5) | 1.2 (0.41 to 3.4) | 0.84 |

| Gestational hypertension | 54 (5.1) | 50 (5.1) | 4 (6.0) | 1.2 (0.28 to 5.5) | 0.74 |

| Preeclampsia | 52 (4.9) | 49 (4.9) | 3 (4.5) | 0.9 (0.27 to 2.9) | 0.86 |

| Preterm birth | 140 (13.3) | 130 (13.1) | 10 (14.9) | 1.15 (0.57 to 2.3) | 0.67 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 15 (1.4) | 13 (1.3) | 2 (3.0) | 2.3 (0.51 to 20.5) | 0.26 |

| Caesarean section | 542 (51.3) | 505 (51) | 37 (55.2) | 1.18 (0.72 to 1.95) | 0.50 |

| Obstetric haemorrhage | 28 (2.6) | 26 (2.6) | 2 (3.0) | 1.14 (0.26 to 4.9) | 0.86 |

| Neonate large for gestational age | 33 (3.1) | 32 (3.3) | 1 (1.5) | 0.45 (0.06 to 3.3) | 0.42 |

| Neonate small for gestational age | 122 (11.6) | 117 (11.2) | 5 (7.5) | 0.59 (0.23 to 1.5) | 0.27 |

| Congenital malformations | 28 (2.6) | 28 (2.6) | 2 (3.0) | 1.14 (0.26 to 4.9) | 0.86 |

*Diagnosed using International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria.

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

The present study showed that a fasting glucose cut-off value of ≥90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) exhibited good sensitivity and specificity for GDM screening in Mexican adolescents. Using this cut-off value improved the ability to identify healthy patients and reduced the need to perform an OGTT to confirm/exclude the diagnosis of GDM, resulting in similar detection rates. This study is the first to report the prevalence of GDM in an adolescent population using IADPSG criteria and describe perinatal outcomes in GDM adolescent women without treatment.

Fasting glucose was altered in 90.1% of GDM cases (n=64), but altered glucose values in the 2-hour 75 g OGTT were only found in 7% of women at 1 hour and 9.9% at 2 hours. This suggests that fasting glucose can be used as a screening tool for GDM in this population. Although the potential of fasting glucose as a screening strategy has been reported in previous studies in adult women,20 23 no studies have used IADPSG criteria to diagnose GDM in adolescent women. The first unbiased study to suggest this diagnostic strategy was published in 1998 by Reichelt et al,24 who reported sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 66% using a fasting glucose cut-off value of ≥85 mg/dL (4.72 mmol/dL) in adult Brazilian women. A meta-analysis conducted by Donovan et al 20 reported seven studies that used fasting glucose for GDM screening; however, all of those studies diagnosed GDM with Carpenter and Coustan criteria, and fasting glucose cut-offs values of ≥85 mg/dL (4.72 mmol/L) and ≥95 mg/dL (5.27 mmol/L) resulted in sensitivity and specificity values of 87% and 52% and 54% and 93%, respectively.

In 2010, Agarwal et al 19 published a study involving 10 283 pregnant women (maternal age: 28.3±6.1 years) from the United Arab Emirates. Using IADPSG criteria, those authors reported that fasting glucose cut-offs of 75 mg/dL (4.16 mmol/L), 85 mg/dL (4.72 mmol/L) and 92 mg/dL (5.11 mmol/L) resulted in sensitivity and specificity values of 98.3% and 11.3%, 88.9% and 60% and 76.8% and 100%, respectively.19 Although these populations are not comparable, the sensitivity and specificity found in this study using glucose cut-off values of 85 and 90 mg/dL (4.72 and 5.0 mmol/L) in Mexican adolescents were higher. In the present study, the abnormal fasting glucose rate was higher than that used in the HAPO study for GDM diagnosis, in which the higher rates were 74% for women from Barbados and 73% for women from Bellflower, California.25 This discrepancy may be explained by maternal age and ethnic group. The mean maternal age in the present study was 16.2±1.6 years, while that in the HAPO study was 29.2±5.8 years. Gopalakrishnan et al 26 reported that 91.4% of adult North Indian women with GDM according to IADPSG criteria had abnormal FPG, which was similar to findings in the present study. Similarly, Trujillo et al 27 reported an area under the curve of 0.96 in adult Brazilian women for fasting glucose values to detect GDM as defined by IADPSG diagnostic criteria. In the same study, an FPG cut-off value of 85 mg/dL indicated that only 18.7% of all women needed to undergo an OGTT, with a detection rate of 92.5% of all GDM cases, whereas a cut-off of 90 mg/dL had a detection rate of 88.3% GDM cases (indicating an OGTT would be necessary in only 4.2% of all women).27 These findings were similar to those of the present study. If these results are confirmed, OGTT could be avoided in Mexican adolescent women because 90.1% of women with GDM can be diagnosed using fasting glucose, in accordance with IADPSG criteria.

The prevalence of GDM in adolescent women at INPer increased significantly from 0.4% using current criteria to 6.7% using IADPSG criteria; however, 38% of pregnant adolescents attended during the study period did not have clinical records of GDM screening because they only arrived for delivery. The perinatal outcomes in the present study were similar in adolescents with and without GDM, even though 94.3% of adolescents with GDM did not receive GDM-specific treatment. This finding was consistent with the cost–benefit analysis reported by Werner et al,28 who concluded that the perinatal benefits associated with use of the IADPSG criteria did not justify the additional costs associated with a threefold increase in the number of women diagnosed with GDM. However, using the IADPSG criteria may be beneficial for this young and vulnerable group. If their conversion rate to type 2 diabetes is the same as shown in previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses,29 30 they would likely develop type 2 diabetes at a young age; an opportune intervention could reduce the long-term incidence of type 2 diabetes. A recent systematic review indicated that interventions addressing health behaviour in women with previous GDM starting up to 1-year postpartum was superior to no intervention with regard to type 2 diabetes prevention.31 In addition, these women are likely to have subsequent pregnancies and recurrent GDM.32

This study had several limitations. The study was retrospective, the diagnostic validity of the test has not yet been confirmed in a second independent population and the results are only applicable to Mexican (and potentially Latin) adolescent women. Future prospective and multicentre studies are required to corroborate these findings. Another limitation was that the available sample size to compare perinatal outcomes between women with and without GDM was insufficient. Future studies with appropriate power are needed to confirm these results.

Most adolescent women at INPer request prenatal care in the middle of the second trimester. This is similar to a study by Lira Plascencia et al 33 who reported the mean gestational age at the first prenatal visit among 2315 pregnant in the same institution was 24.2±6.7 weeks of gestation. It is important to note that two adolescents with overt diabetes (type 2 diabetes) were identified in early pregnancy and were excluded from the analysis; this is consistent with reported trends in the prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among the Hispanic youth population that increased from 0.96 to 1.29 and 0.45 to 0.79 per 1000 women, respectively, between 2001 and 2009.34

According to the IADPSG,12 ADA,2 Endocrine Society,12 WHO,14 FIGO,15 ACOG,16 NICHHD18 and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada,3 all pregnant adolescents should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. This intervention has an impact on the cost of prenatal care in the health systems of low/middle-income countries including Mexico, regardless of the low prevalence of GDM in adolescents compared with the adult population and the lack of evidence about the benefits of treatment on perinatal outcomes using IADPSG criteria. However, the diagnosis of GDM in adolescents along with an appropriate intervention programme may decrease the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in this population in the long term.

Future research should further investigate the use of fasting glucose as a screening tool to identify candidates for OGTT, the benefits of treating GDM in adolescent women, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes during the first trimester of pregnancy and the risk for type 2 diabetes in adolescent women with GDM in the long term.

Conclusions

An FPG cut-off value of ≥90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) is ideal for GDM screening in Mexican adolescent women. An FPG threshold of 90 mg/dL would miss 6 (8.5%) women with GDM, pick up 34 (3.4%) women without GDM and avoid 962 (90.7%) OGTTs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Audrey Holmes, MA, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: ER-M, NLS-O and JL-P conceived and designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the paper. NM-C, LA-S, CO-G and GE-G analysed the data and reviewed the paper. NLS-O, CR-M, MAR-T and AM-E acquired the data, interpreted the results and reviewed the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by National Council of Science and Technology, CONACYT, Mexico (Grant no. 233634) and Instituto National de Perinatología Isidro Espinosa de los Reyes, Mexico City (Registry ID: 212250-3402-10102-02-14).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Internal Review Board of the Instituto Nacional de Perinatología in Mexico City (register number: 212250-3402-10102-02-14).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/maternal/adolescent_pregnancy/en/ (accessed 18 Jan 2017).

- 2. American Diabetes Association. (2) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38 (Suppl):S8–S16. 10.2337/dc15-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleming N, O’Driscoll T, Becker G, et al. Adolescent pregnancy guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:740–56. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30180-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khine ML, Winklestein A, Copel JA. Selective screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in adolescent pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:738–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramírez-Torres MA, Rodríguez-Pezino J, Zambrana-Castañeda M, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and glucose intolerance among Mexican pregnant adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2003;16:401–5. 10.1515/JPEM.2003.16.3.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;144:768–73. 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90349-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reyes-Muñoz E, Parra A, Castillo-Mora A, et al. Effect of the diagnostic criteria of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups on the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in urban Mexican women: a cross-sectional study. Endocr Pract 2012;18:146–51. 10.4158/EP11167.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Minjares-Granillo RO, Reza-López SA, Caballero-Valdez S, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes among adolescents and mature women: a hospital-based study in the north of Mexico. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2016;29:304–11. 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lira-Plascencia J, Oviedo-Cruz H, Pereira LA, et al. Analysis of the perinatal results of the first five years of the functioning of a clinic for pregnant teenagers. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2006;74:241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ortiz-Hernández L, Gómez-Tello BL. Food consumption in Mexican adolescents. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2008;24:127–35. 10.1590/S1020-49892008000800007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Metzger BE, Lowe LP; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2002;2008:1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e98–82. 10.2337/dc10-0719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4227–49. 10.1210/jc.2013-2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. WHO/NMH/MND/13.2. Geneva: WHO Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131 (Suppl 3):S173–S211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:406–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vandorsten JP, Dodson WC, Espeland MA, et al. NIH consensus development conference: diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2013;29:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diabetes in pregnancy: management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period Clinical guidelines. London: National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK), 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Shah SM. Gestational diabetes mellitus: simplifying the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy diagnostic algorithm using fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2018–20. 10.2337/dc10-0572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donovan L, Hartling L, Muise M, et al. Screening tests for gestational diabetes: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:115–22. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30 (Suppl 2):S251–S260. 10.2337/dc07-s225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flores-Huerta S, Martínez-Salgado H. Birth weight of male and female infants born in hospitals affiliated with the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2012;69:30–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agarwal MM. Gestational diabetes mellitus: screening with fasting plasma glucose. World J Diabetes 2016;7:279–89. 10.4239/wjd.v7.i14.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reichelt AJ, Spichler ER, Branchtein L, et al. Fasting plasma glucose is a useful test for the detection of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1246–9. 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sacks DA, Hadden DR, Maresh M, et al. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus at collaborating centers based on IADPSG consensus panel-recommended criteria: the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:526–8. 10.2337/dc11-1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gopalakrishnan V, Singh R, Pradeep Y, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in North Indians using the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study groups (IADPSG) criteria. J Postgrad Med 2015;61:155–8. 10.4103/0022-3859.159306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trujillo J, Vigo A, Reichelt A, et al. Fasting plasma glucose to avoid a full OGTT in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;105:322–6. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Werner EF, Pettker CM, Zuckerwise L, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: are the criteria proposed by the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups cost-effective? Diabetes Care 2012;35:529–35. 10.2337/dc11-1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:1773–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, et al. Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia 2016;59:1403–11. 10.1007/s00125-016-3927-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pedersen ALW, Terkildsen Maindal H, Juul L. How to prevent type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes? A systematic review of behavioural interventions. Prim Care Diabetes 2017;11:403–13. 10.1016/j.pcd.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwartz N, Nachum Z, Green MS. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus recurrence-effect of ethnicity and parity: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:310–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lira Plascencia J, Oviedo Cruz H, Pereira LA, et al. [Analysis of the perinatal results of the first five years of the functioning of a clinic for pregnant teenagers]. Ginecol Obstet Mex 2006;74:241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA 2014;311:1778–86. 10.1001/jama.2014.3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.