Abstract

Objective: To describe national annual prescribing patterns of stimulant, antidepressant, and antipsychotic medications to young people.

Methods: Prescriptions for three commonly prescribed psychotropic classes (stimulants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics) to young people aged 3–24 years were analyzed from the IMS LifeLink LRx National Longitudinal Prescription database (n = 6,351,482). Denominators were adjusted to generalize estimates to the U.S. population. Comparisons are presented of percentages filling ≥1 prescription of each medication class during the study year stratified by patient sex, age, and prescriber specialty.

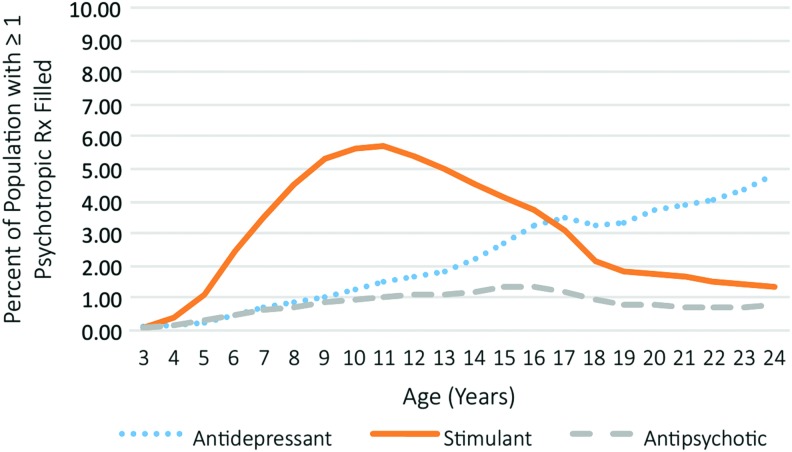

Results: The total annual percentage of prescriptions filled by youth for any of the three medication classes was by age 3–5 years (0.8%), 6–12 years (5.4%), 13–18 years (7.7%), and 19–24 years (6.0%). Stimulant use was highest for older children (age 11 = 5.7%). Antidepressant use tended to increase with age and was highest for young adults (age 24 = 4.8%). Annual antipsychotic prescription percentages were lower than antidepressant or stimulant percentages for all age groups, with a peak in adolescence (age 16 = 1.3%). Annual stimulant and antipsychotic percentages for males were higher than corresponding percentages for females, but converged for young adults. Psychiatrists and child psychiatrists accounted for most of the prescriptions of antidepressants (22.2%–53.2%) and antipsychotics (51.7%–70%), but fewer of the stimulant prescriptions (30.4%–36.2%).

Conclusions: The age and sex distribution of stimulants and antidepressants among young people is broadly consistent with known epidemiologic patterns of their established indications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and depression. The pattern of antipsychotics may reflect the heterogeneity of disorders and conditions treated with this medication class.

Keywords: : ADHD, antipsychotic, antidepressant, stimulant, psychopharmacology, psychopharmacoepidemiology

Introduction

Stimulants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics are important psychopharmacological treatments for young people. Based on randomized controlled trials, stimulant medications are well established for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (The MTA Cooperative 1999; Chan et al. 2016). Antidepressant medications are generally supported for the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders (Bridge et al. 2007; March et al. 2007; Walkup et al. 2008; Cipriani et al. 2016). Last, antipsychotic medications demonstrate efficacy in schizophrenia (Sikich et al. 2008; Schimmelmann et al. 2013; Harvey et al. 2016), bipolar disorder (Correll et al. 2010; Vitiello et al. 2012), and clinical aggression in youth with and without autism (Shea et al. 2004; Reyes et al. 2006; Scotto Rosato et al. 2012; Aman et al. 2014; Gadow et al. 2014; Pringsheim et al. 2015).

There is growing interest regarding the alignment of psychotropic medication prescribing patterns with the epidemiology of common childhood psychiatric conditions. For example, concerns exist regarding rising use of prescribed pharmacological agents for youth (Olfson et al. 2010, 2014a), particularly in young children (Zito et al. 2000; Olfson et al. 2010) in the United States. Concurrently, epidemiological studies raise concerns over potential undertreatment of ADHD in school-aged children (Jensen et al. 1999) and depression in youth (Libby et al. 2009). Together, these lines of research raise questions regarding the appropriateness of psychotropic medication prescribing for youth.

The American Association of Pediatrics has provided guidelines for assessment and treatment of ADHD (Cheung et al. 2007) and depression (Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder 2011) in pediatric practice. For many youth, pediatricians and other primary care physicians are their sole source of mental health treatment. Previous work has narrowly examined the question of medical specialties and prescribing practices. For example, past research has examined antipsychotic prescriptions and the psychiatric specialties who prescribe them (Olfson et al. 2006, 2015a), as well as the distribution of outpatient mental health diagnoses among medical specialties (Olfson et al. 2014a). Little is known about prescribing patterns of stimulants and antidepressants, particularly by nonpsychiatric specialties, such as pediatrics. Much of previous work has been based on single payer, noncomposite data sources (Olfson et al. 2006, 2015a). An understanding of the extent to which different physician specialties, including pediatrics, psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and others, prescribe psychotropic medications to young people would help characterize their respective roles in the community treatment of mental health conditions and potentially identify opportunities for rebalancing prescribing practices.

Despite considerable interest in psychotropic medication prescribing to younger populations in the United States, our knowledge remains fragmented. Although some analyses have focused on individual drug classes, notably stimulants and antipsychotics (Zuvekas and Vitiello 2012; Olfson et al. 2015a), less attention has been devoted to comparing and contrasting filled prescriptions of these psychotropic medication classes by sex and single year of age, or included more than one class of medication.

We analyzed the national distribution of stimulant, antidepressant, and antipsychotic prescriptions by single year of age, age group, sex, and physician specialty type using national prescribing claims from all payment sources. These results build on earlier descriptive analyses of individual drug classes (Olfson et al. 2015a, 2016) and separate analyses of publicly and privately insured populations to generate a combined analysis of public, private, and out-of-pocket claims (Olfson et al. 2010). Framing this analysis in an age-related context provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent to which national pharmacological treatment patterns map onto known national epidemiologic prevalence, age, and sex distributions of common mental disorders of young people.

Methods

Data sources

Data were acquired from the 2008 IMS LifeLink LRx Longitudinal Prescription database (n = 6,351,482) and the 2008 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2015). The IMS LifeLink LRx database provided data from filled prescriptions for psychotropic medications by prescriber specialty, sex, and age, as well as the total population covered by the database by sex and age.

The LifeLink LRx data contain deidentified individual prescriptions from ∼33,000 retailers. The IMS data captured the majority of all retail prescriptions in the United States and were nationally representative with respect to age, sex, and payment source. Given the deidentified nature of the data source, these analyses were determined to be exempt from IRB approval.

Design and analytic sample

A population-level retrospective observational study was performed of filled prescriptions for selected common psychotropic medication prescriptions (stimulants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics) in U.S. youth between 3 and 24 years of age.

Variable construction

Youth were divided by sex and into four age groups: younger children (3–5 years), older children (6–12 years), adolescents (13–18 years), and young adults (19–24 years). Medication groups included stimulants (any methylphenidate or amphetamine salt compounds), antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and atypical antidepressants), and antipsychotics (first and second generation). Other psychiatric medications such as mood stabilizers (anticonvulsants), tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines were not examined given their common use for nonpsychiatric conditions. Medication prescribing was defined as the percentage of individuals who filled at least one prescription of that class at a pharmacy during the study year. The final study population included youth who filled a prescription for at least one of the three medication classes during the study year at a retail or mail order pharmacy.

Statistical analysis

To account for individuals who did not fill a prescription, the IMS database denominators were adjusted using the MEPS data (Olfson et al. 2015b). This estimation allows the IMS prescription data to yield annual medication prescribing percentages for the U.S. population of young people.

We estimated the total percent of youth, for each age group, who were prescribed any of these three psychotropic medications. We also calculated the percentage who were prescribed each of the three classes by age group and sex for the study year. Percentages of filling of each psychotropic medication class by single year of age and by sex were plotted separately. Finally, separate analyses estimated the distribution of total prescriptions for each psychotropic class by prescriber type: pediatrics, psychiatry, child psychiatry, and other specialties (all other remaining specialties).

Results

National estimates for the study population

The 2008 IMS LRx database included 131,291 younger children, 2,140,289 older children, 2,163,202 adolescents, and 1,916,700 young adults who filled ≥1 stimulant, antidepressant, or antipsychotic prescription (total n = 6,351,482). If these figures are projected to the national population, they would represent ∼209,000 (0.8%) young children, 3.4 million (5.4%) older children, 3.4 million (7.7%) adolescents, and 3.0 million (6.1%) young adults who filled at least once prescription for one or more of the three psychotropic medication classes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Annual Prevalence Estimates of Any Stimulant-, Antidepressant-, or Antipsychotic-Filled Prescriptions (One or Greater) by Patient Age Group and Sex, United States, 2008

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–5 | 6–12 | 13–18 | 19–24 | |

| U.S. population | % | % | % | % |

| With selected common psychotropic prescription in year | 0.8 | 5.4 | 7.7 | 6.0 |

| Males | 1.1 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 4.6 |

| Females | 0.5 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 7.6 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated.

Patterns of major psychotropic medication prescriptions by age and sex

The percentages of young people who filled psychotropic prescriptions were determined by single year of patient age and medication class (Fig. 1). Stimulant prescription percentages were highest in the older children group, peaking at 11 years of age (5.7%). Antidepressants tended to increase from age 3–13 years with a more rapid increase when older than 14 years. In each age group, the percentage of young people who filled antipsychotic prescriptions was lower than the percentages who filled stimulant or antidepressant medications. The percentage of prescribed antipsychotics peaked at 16 years of age (1.3%).

FIG. 1.

Percentage of youth with one or greater filled prescription for an antidepressant, stimulant, or antipsychotic by age, United States, 2008. *IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cap

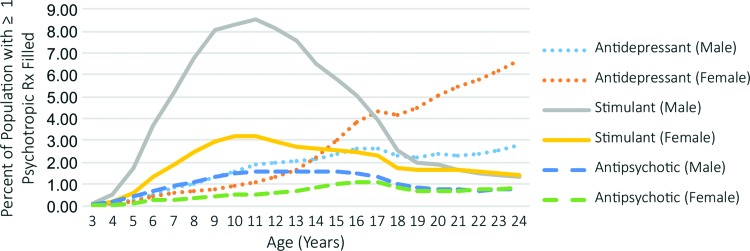

Table 2 presents these results segmented by developmental stages, including young children (3–5 years), older children (6–12 years), adolescents (13–18 years), and young adults (19–24 years). Figure 2 displays the percentages of young people filling at least one psychotropic prescription by single year for age, sex, and medication class. When separated by sex, the percentage of males who filled stimulant prescriptions sharply increased from age 4–11 years, sharply decreased from age 12–18 years, and slowly declined thereafter. Prescriptions of stimulants for females demonstrated a similar trend with a lower amplitude that merged with male stimulant prescriptions at age 21 years. The percentages of males and females who filled ≥1 antidepressant prescription were similar until the age of 14 years after which there was a sharp increase for females. Antipsychotic prescription percentages were higher among males than females until the age of 18 years and began to converge for young adults.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Youth with One or Greater Filled Prescription of Selected Common Psychotropic Medication by Class and Sex, United States, 2008

| Antidepressant | Stimulant | Antipsychotic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | All% | Male% | Female% | All% | Male% | Female% | All% | Male% | Female% |

| Younger children (3–5 years) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Older children (6–12 years) | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Adolescents (13–18 years) | 2.8 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Young adults (19–24 years) | 4.0 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of population with one or greater filled prescription for an antidepressant, stimulant, or antipsychotic by sex and age, United States, 2008. *IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/cap

Psychotropic prescriptions by provider specialty

For each year of age younger than 18 years, pediatricians wrote the numerically largest percentage of filled stimulant prescriptions (∼43%), and a smaller percentage of antidepressant (∼13%) and antipsychotic (∼11%) prescriptions (Table 3). Prescriptions for antipsychotics were fairly evenly distributed among specialties for younger children with psychiatrists (23%–28%) and child psychiatrists (7%–26%), accounting for a larger share of the older age groups (Table 3). The residual “other specialties” group wrote the largest percentage of filled antidepressant prescriptions (34%–70%), followed by psychiatrists (14%–28%) and child psychiatrists (7%–26%), to each of the four age groups.

Table 3.

Distribution of One or Greater Filled Psychotropic Prescription by Class and Medical Specialty of Prescriber, United States, 2008

| 3–5 years old | 6–12 years old | 13–18 years old | 19–24 years old | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressant (total) | 104,529 | 1,657,388 | 3,847,245 | 5,006,450 |

| Pediatrics | 9.2% | 15.4% | 11.8% | 3.3% |

| General psychiatry | 14.0% | 23.7% | 28.2% | 28.0% |

| Child psychiatry | 8.2% | 26.6% | 25.0% | 7.3% |

| Other specialties | 68.7% | 34.6% | 34.9% | 61.4% |

| Stimulant (total) | 269,672 | 8,773,541 | 6,026,603 | 2,368,351 |

| Pediatrics | 42.9% | 43.7% | 37.3% | 13.3% |

| General psychiatry | 16.6% | 14.4% | 17.4% | 25.9% |

| Child psychiatry | 17.9% | 16.0% | 17.6% | 10.3% |

| Other specialties | 22.6% | 23.9% | 27.6% | 50.5% |

| Antipsychotic (total) | 102,437 | 1,677,169 | 1,965,133 | 1,180,122 |

| Pediatrics | 21.3% | 11.6% | 6.2% | 1.8% |

| General psychiatry | 26.1% | 32.6% | 38.7% | 55.7% |

| Child psychiatry | 25.6% | 35.4% | 35.7 | 14.3% |

| Other specialties* | 27.0% | 20.3% | 20.1% | 28.2% |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated.

Other specialties include all other medical specialties, excluding pediatrics and psychiatry.

Discussion

Among young people in the United States, the patterns of filled prescriptions for antidepressants and stimulants are broadly consistent with developmental onsets of the common mental disorders from early childhood to young adulthood. However, the percentages of young people prescribed stimulant and antidepressant medications were lower than the known prevalence of corresponding disorders, and the demographic pattern of antipsychotic prescribing likely represents the heterogeneity of conditions treated with this class of medications.

Stimulants and ADHD

Consistent with the observations that ∼80% of lifetime ADHD is diagnosed in the age range of 4–11 years, the peak increase in stimulant prescribing occurred between ages of 5 and 11 years (Kessler et al. 2007). ADHD symptoms, particularly impulsivity and hyperactively, appear to decrease with age. In accord with the roughly one-third of children with ADHD who continue to have symptoms as adults (Kessler et al. 2005; Barbaresi et al. 2013; Holbrook et al. 2016), there was a decrease in the proportion of individuals who received stimulants during adolescence and young adulthood. The higher percentage of males than females who filled stimulant prescriptions is in line with community epidemiological studies of the prevalence of ADHD, which is ∼2.5 times more common in boys than girls (Staller and Faraone 2006; Olfson et al. 2016). However, this finding may support ongoing concerns regarding underdiagnoses and treatment of ADHD in girls (Quinn and Madhoo 2014). Interestingly, the convergence of stimulant prescribing percentages for males and females in their 20s is consistent with the similar prevalence of adult ADHD symptoms in men and women (Cortese et al. 2016).

While concern exists regarding potential overprescribing of stimulants (Jensen et al. 1999), our results of stimulant treatment for older children (4.6%) and adolescents (3.8%) are below published national community prevalence estimates of ADHD (8.6%) (Merikangas et al. 2010). The relatively low stimulant treatment percentages compared to epidemiological disorder prevalence remain, even assuming pharmacologic treatment is only necessary for those with moderate to severe conditions, ∼75% of ADHD cases (Kessler et al. 2012). Last, our reported percentages are similar to available studies of stimulant use in youth (Zoëga et al. 2009; Olfson et al. 2010, 2015c).

Antidepressants and mood and anxiety disorders

The prevalence of depression, particularly for females, tends to increase around the age of 13 years (Costello et al. 2002; Merikangas et al. 2010). Our observed increase in antidepressants for adolescents and young adults is consistent with the pubertal risk of development of mood disorders (Angold and Worthman 1993). Higher antidepressant prescribing for adolescent and young adult females than males is also in line with the known higher female than male prevalence of anxiety and depression in this population (Costello et al. 2005, 2006; Beesdo et al. 2009).

Similar to stimulants and ADHD, gaps exist between the percentage of young people prescribed antidepressants and epidemiological estimates of the prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders. Adolescent prevalence estimates for depression range from 4% to 5% (Costello et al. 2005, 2006) and for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents from 15% to 20% (Beesdo et al. 2009). The annual antidepressant prescribing in this population was 2.8%, which is similar to previously reported rates (Zoëga et al. 2009; Olfson et al. 2015c). This observed gap remains even when assuming only those with moderate to severe disease should receive pharmacologic treatment: 40% of all anxiety disorders and 60% of depressive disorders in a community sample are at a moderate to severe level (Kessler et al. 2012). Interestingly, the percentage of females filling antidepressant prescriptions increased and separated from corresponding male percentages during the late teens. This pattern reflects a previously reported association between female sex and treatment seeking for depression (Mojtabai and Olfson 2006).

Antipsychotics and treated disorders

Antipsychotic medications have a wide and heterogeneous set of off-label and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved conditions (Reyes et al. 2006; Aman et al. 2014). Combined lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorders and mood disorders with related psychoses may reach as high as 3.6%; however, most of these disorders develop in adolescence or later (Perälä et al. 2007). Recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates of the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder are as high as 1.5%, although not all of these youth have irritability, which is the related target for antipsychotic treatment (Christensen et al. 2016). In our study, annual percentages of filled antipsychotic prescriptions for younger children, older children, and adolescent youth were comparatively lower compared with antidepressant and stimulant medications. Previous research has shown that FDA-approved indications for antipsychotics (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Tourette's disorder, and irritability/aggression associated with autistic disorder) do not account for all of the antipsychotic prescriptions to young people (Alexander et al. 2011). The observed antipsychotic prescription patterns, which are similar to past published rates (Zoëga et al. 2009; Olfson et al. 2010, 2015c), likely represent a compilation of FDA-approved conditions, including childhood bipolar disorder, as well as of evidence-based, but non-FDA approved indications, such as severe behavioral disturbances in ADHD (Reyes et al. 2006; Aman et al. 2014).

Distribution of psychotropic prescriptions by prescriber specialty

Consistent with the view that pediatricians include ADHD treatment within their scope of practice (Stein et al. 2008), they accounted for a large percentage of stimulant prescribing. Antidepressant prescribing was predominately from child and adolescent or general psychiatrists, and other specialties. This pattern is different from the treatment of adult depression where primary care physicians play a predominant role in antidepressant prescribing (Olfson et al. 2014b). Low prescribing of antidepressants by pediatricians is potentially concerning given high rates of anxiety and depression among youth (Costello et al. 2005, 2006; Beesdo et al. 2009) and evidence of undertreatment of depression in youth (Mojtabai et al. 2016). Pediatricians may have a significantly higher comfort level diagnosing ADHD and prescribing stimulants than diagnosing depression or anxiety and prescribing antidepressants (Fremont et al. 2009).

Challenges exist in identifying and addressing potential undertreatment of mood and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents in pediatric practice and other primary care settings. The well-established shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists could be partially offset through telepsychiatry (Myers and Cain 2008) and consultation services to primary care (Keller and Sarvet 2013) in an effort to improve the recognition and treatment of uncomplicated cases in primary care (Sarvet et al. 2010; Straus and Sarvet 2014).

The presented analyses have several limitations. First, the IMS prescription data capture medicines purchased rather than consumed, and we are unable to estimate the proportion of youth who received ongoing pharmacological treatment. Second, information was not available concerning symptoms, severity, distress, and functional impairment, or clinical diagnoses. Without diagnostic data, we are unable to determine the extent to which individuals treated with these medications have an indicated disorder (Olfson et al. 2013). As a result, our discussion of epidemiologic prevalence of disorders in relation to treatment rates should be viewed as exploratory. Third, we are unable to disaggregate the overall findings into separate payers, such as public insurance, private insurance, or out of pocket payments. Finally, the analyses are based on 2008 dispensing patterns and since that time, prescribing practices may have changed. However, recent analyses examining prescribing rates in children younger than 17 years suggest that overall antipsychotic rates are similar and stabilizing (Crystal et al. 2016).

Conclusions

At a population level, the age and sex contours of antidepressant and stimulant treatment patterns in the United States broadly conform to the underlying developmental epidemiology of depression, anxiety, and ADHD. Antipsychotic treatment patterns, while lower than antidepressants and stimulants, likely reflect the summation of FDA-indicated and off-label uses in youth. Given concerns regarding off-label use of antipsychotics, further research into potential FDA indications, real-world safety, and effectiveness of antipsychotics would help clarify their role in the care of young people. Improving access to child psychiatrists through consultation services and collaborative care models may help address potential undertreatment and reduce unnecessary medication prescribing.

Overall, the findings provide some reassurance regarding population level prescribing patterns of psychotropic medications in youth in relation to the epidemiologic distribution of major child and adolescent mental disorders. However, we should continue to monitor psychotropic medication prescriptions over time to assess whether U.S. prescribing practices remain broadly consistent with underlying disorder prevalence. Finally, additional epidemiologic studies with more detailed and structured clinical information are needed to better understand the patterns and pathways of psychotropic medication prescriptions for youth.

Clinical Significance

Among young people, the population level prescribing rates as well as age and sex distributions of stimulant and antidepressant are broadly consistent with known epidemiologic patterns of their established indications for ADHD, anxiety, and depression. Patterns of antipsychotics are more complex and may reflect the heterogeneity of the approved and off-label conditions and disorders treated with this medication class.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this study are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the National Institute of Mental Health, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the federal government.

Disclosures

Financial Disclosure: The authors indicate they have no financial relationships relevant to this article. Potential Conflicts of Interests: Drs. Sultan, Olfson, and Schoenbaum report no conflict to disclose. Dr. Correll has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, The Bendheim Foundation, and Takeda. He has served as a member of advisory boards/the Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Alkermes, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Sunovion. He has served as a consultant to Alkermes, Allergan, the Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, Medscape, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda. He has presented expert testimony for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka. He has received honorarium from Medscape. He has received travel expenses from Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Takeda. Dr. Walkup has past research support for federally funded studies, including free drug and placebo from Pfizer's pharmaceuticals in 2007 to support the Child Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal study; free medication from Abbott pharmaceuticals in 2005 for the Treatment of the Early Age Media study; and free drug and placebo from Eli Lilly in 2003 for the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression study. He currently receives research support from the Tourette's Association of America and the Hartwell Foundation. He also receives royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford Press for multiauthor books published about Tourette syndrome.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: MEPS-HC panel design and data collection process. http://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp (accessed November5, 2015)

- Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS: Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20:177–184, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Bukstein OG, Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Molina BS, McNamara NK, Rundberg-Rivera EV, Li X, Kipp H, Schneider J, Butter EM, Baker J, Sprafkin J, Rice RR, Jr, Bangalore SS, Farmer CA, Austin AB, Buchan-Page KA, Brown NV, Hurt EA, Grondhuis SN, Findling RL: What does risperidone add to parent training and stimulant for severe aggression in child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:47–60, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Worthman CW: Puberty onset of gender differences in rates of depression: A developmental, epidemiologic and neuroendocrine perspective. J Affect Disord 29:145–158, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK: Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study. Pediatrics 131:637–644, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS: Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am 32:483–524, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, Ren L, Brent DA: Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 297:1683–1696, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E, Fogler JM, Hammerness PG: Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: A systematic review. JAMA 315:1997–2008, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE: GLAD-PC steering group. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics 120:e1313–e1326, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, Daniels J, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Kurzius-Spencer M, Lee LC, Pettygrove S, Robinson C, Schulz E, Wells C, Wingate MS, Zahorodny W, Yeargin-Allsopp M; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ 65:1–23, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B, Whittington C, Coghill D, Zhang Y, Hazell P, Leucht S, Cuijpers P, Pu J, Cohen D, Ravindran AV, Liu Y, Michael KD, Yang L, Liu L, Xie P: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Lancet 388:881–890, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Sheridan EM, DelBello MP: Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: A comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 12:116–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Faraone SV, Bernardi S, Wang S, Blanco C: Gender differences in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 77:e421–e428, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A: 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:972–986, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A: Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:1263–1271, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Pine DS, Hammen C, March JS, Plotsky PM, Weissman MM, Biederman J, Goldsmith HH, Kaufman J, Lewinsohn PM, Hellander M, Hoagwood K, Koretz DS, Nelson CA, Leckman JF: Development and natural history of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 52:529–542, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal S, Mackie T, Fenton MC, Amin S, Neese-Todd S, Olfson M, Bilder S: Rapid growth of antipsychotic prescriptions for children who are publicly insured has ceased, but concerns remain. Health Aff 35:974–982, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont WP, Nastasi R, Newman N, Roizen NJ: Comfort level of pediatricians and family medicine physicians diagnosing and treating child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Int J Psych Med 38:153–168, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Molina BS, Findling RL, Bukstein OG, Brown NV, McNamara NK, Rundberg-Rivera EV, Li X, Kipp HL, Schneider J, Farmer CA, Baker JL, Sprafkin J, Rice RR, Jr, Bangalore SS, Butter EM, Buchan-Page KA, Hurt EA, Austin AB, Grondhuis SN, Aman MG: Risperidone added to parent training and stimulant medication: Effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and peer aggression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:948–959, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RC, James AC, Shields GE: A systematic review and network meta-analysis to assess the relative efficacy of antipsychotics for the treatment of positive and negative symptoms in early-onset schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 30:27–39, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JR, Cuffe SP, Cai B, Visser SN, Forthofer MS, Bottai M, Ortaglia A, McKeown RE: Persistence of parent-reported ADHD symptoms from childhood through adolescence in a community sample. J Atten Disord 20:11–20, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, Sloan MT, Dulcan MK, Hoven C, Bird HR, Bauermeister JJ, Payne JD: Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:797–804, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller D, Sarvet B: Is there a psychiatrist in the house? Integrating child psychiatry into the pediatric medical home. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:3–5, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Faraone SV, Greenhill LL, Jaeger S, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Zaslavsky AM: Patterns and predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 57:1442–1451, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB: Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20:359–364, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Green JG, Gruber MJ, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR: Severity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:381–389, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ: Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:633–639, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, Burns B, Domino M, McNulty S, Vitiello B, Severe J: The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1132–1143, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics 125:75–81, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M: Treatment seeking for depression in Canada and the United States. Psychiatr Serv 57:631–639, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B: National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 138:e20161878, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, MCain S; The AACAP; Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for telepsychiatry with children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:1468–1483, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G: National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:679–685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU: National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry 71:81–90, 2014a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T: Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:13–23, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC: Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 372:2029–2038, 2015c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, He JP, Merikangas KR: Psychotropic medication treatment of adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:378–388, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72:136–142, 2015b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Stimulant treatment of young people in the United States. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 26:520–526, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Treatment of young people with antipsychotic medications in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72:867–874, 2015a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Kroenke K, Wang S, Blanco C: Trends in office-based mental health care provided by psychiatrists and primary care physicians. J Clin Psychiatry 75:247–253, 2014b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Kuoppasalmi K, Isometsä E, Pirkola S, Partonen T, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Hintikka J, Kieseppä T, Härkänen T, Koskinen S, Lönnqvist J: Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:19–28, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, Gorman DA: The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: Antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers. Can J Psychiatry 60:52–61, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P, Madhoo M: A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: Uncovering this hidden diagnosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 16:PCC.13r01596, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M, Buitelaar J, Toren P, Augustyns I, Eerdekens M: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone maintenance treatment in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. Am J Psychiatry 163:402–410, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvet B, Gold J, Bostic JQ, Masek BJ, Prince JB, Jeffers-Terry M, Moore CF, Molbert B, Straus JH: Improving access to mental health care for children: The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Pediatrics 126:1191–1200, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelmann BG, Schmidt SJ, Carbon M, Correll CU: Treatment of adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: In search of a rational, evidence-informed approach. Curr Opin Psychiatry 26:219–230, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotto Rosato N, Correll CU, Pappadopulos E, Chait A, Crystal S, Jensen PS; Treatment of Maladaptive Aggressive in Youth Steering Committee: Treatment of maladaptive aggression in youth: CERT guidelines II. Treatments and ongoing management. Pediatrics 129:e1577–e1586, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, Dunbar F: Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics 114:e634–e641, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Ambler D, Puglia M, Maloney AE, Michael E, De Jong S, Slifka K, Noyes N, Hlastala S, Pierson L, McNamara NK, Delporto-Bedoya D, Anderson R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA: Double-blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: Findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry 165:1420–1431, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staller J, Faraone SC: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: Epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs 20:107–123, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein REK, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE: Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr 8:11–17, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus JH, Sarvet B: Behavioral health care for children: The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Health Aff 33:2153–2161, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management; Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM: ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 128:1007–1022, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The MTA Cooperative: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:1073–1086, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Riddle MA, Yenokyan G, Axelson DA, Wagner KD, Joshi P, Walkup JT, Luby J, Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Emslie G, Robb A, Tillman R: Treatment moderators and predictors of outcome in the Treatment of Early Age Mania (TEAM) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:867–878, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar S, March JS, Kendall PC: Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med 359:2753–2766, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F: Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 283:1025–1030, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoëga H, Baldursson G, Hrafnkelsson B, Almarsdóttir AB, Valdimarsdóttir U, Halldórsson M: Psychotropic drug use among Icelandic children: A nationwide population-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:757–764, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B: Stimulant medication use in children: A 12-year perspective. Am J Psychiatry 169:160–166, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]