Abstract

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS), with support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and other funders, held its ninth Bedside-to-Bench research conference, entitled “Urinary Incontinence in the Older Adult: A Translational Research Agenda for a Complex Geriatric Syndrome,” October 16 to 18, 2016, in Bethesda, Maryland. As part of a conference series addressing three common geriatric syndromes—delirium, sleep and circadian rhythm (SCR) disturbance, and urinary incontinence—the series highlighted relationships and pertinent clinical and pathophysiological commonalities between these conditions. The conference provided a forum for discussing current epidemiology, basic science, clinical, and translational research on urinary incontinence in older adults; for identifying gaps in knowledge; and for the development of a research agenda to inform future investigative efforts. The conference also promoted networking involving emerging researchers and thought leaders in the field of incontinence, aging and other fields of research, as well as National Institutes of Health program personnel.

Keywords: aging, urinary incontinence, bladder, voiding dysfunction, epidemiology, mechanisms, interventions

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence (UI) occurs in nearly 40% of women over the age of 80, in 10–35% of older men, and in up to 80% of long term care residents1–4. The impact of UI among older adults is far-reaching beyond impaired quality of life. In a recent evaluation of persons hospitalized with serious illness, bladder and bowel incontinence were rated as conditions worse than death by more than half of the participants (the most undesirable condition among those queried)5. Moreover, older adults with UI are at an increased risk of depression, social isolation, and falls6–8. Incontinence is also associated with loss of independence and ultimately institutionalization in some studies9,10. As a multifactorial geriatric syndrome, UI in older adults occurs when multiple interacting contributing conditions, including multimorbidity (particularly in the setting of cognitive or mobility impairment), changes in lower urinary tract function associated with aging, and medications, overwhelm the individual’s capacity to remain continent11. Treatment options for UI have expanded over the past two decades; however, even with increasing options for treatment and emerging prevention strategies, UI continues to be underreported and undertreated with many afflicted patients failing to report symptoms and many providers ignoring the problem entirely12–14.

Despite the negative impact of UI on health and independence in the context of aging, gaps persist in our understanding of its underlying pathophysiology, particularly with regard to overactive bladder (OAB), an important contributor to UI in older adults. Unanswered questions remain regarding the most beneficial treatment strategies for frail older adults and those living with multiple chronic conditions. Furthermore, questions about UI are generally not included as part of frequently used data sets, such as the NIH Toolbox, designed to encourage assessment of common geriatric syndromes in studies involving older adults. Thus, the current situation provides many opportunities to improve the lives of older adults and to advance the science of aging by overcoming these knowledge gaps and barriers to progress.

URINARY INCONTINENCE AND COMMON PATHWAYS

This U13 conference series focused on three common geriatric syndromes, delirium, sleep and circadian rhythm (SCR) disturbance and UI, with the goal of identifying common shared risk factors and pathophysiologic mechanisms to direct future research efforts. Risk factors common to all geriatric syndromes include older age, decline in functional independence, impaired mobility, and impaired cognition11. Associations between UI, delirium, and SCR appear to be bidirectional. For example, delirium is recognized as a precipitating risk factor or cause of potentially reversible UI. Conversely, anticholinergic drug treatments for urinary symptoms associated with UI have been linked to cognitive decline, particularly among persons with dementia15. Also, urinary symptoms associated with UI, particularly nocturia, are frequently related to SCR disturbance in older adults,16,17 and nocturia may exacerbate wakefulness after sleep onset in those with insomnia disorder16. Conversely, individuals with sleep disturbance, such as sleep apnea or restless leg syndrome, are more likely to report nocturia18,19.

At the U13 conference, a transdisciplinary group of invited experts provided short overviews of the current state of UI science within three broad domains: overlap with other common geriatric syndromes and conditions reflecting potential common pathways, mechanisms of bladder/lower urinary tract function from a basic science and T1 translational perspective, and interventions including models of care delivery. Summaries of these overviews for each domain follow and the resulting collective vision regarding future research priorities.

Common Pathways for UI and Other Geriatric Syndromes – Macro level

Specific chronic diseases along with other disease categories, such as neurologic and cardiovascular diseases, are associated with increased rates of UI.20 Diabetes and obesity represent two chronic disease states that are strongly associated with UI.21,22 Metabolic syndrome also represents an important precursor to diabetes and vascular diseases, but less data exist showing it is a known UI risk factor.23,24 Diabetes, which may result in neurologic and vascular impairments, is associated with a two-fold increase in UI from population-based studies.25,26 Obesity is also associated with increased rates of UI, including both stress and urgency UI subtypes, in epidemiologic studies and clinical trials.22,27,28 Further, there is evidence from several clinical trials that weight loss in persons with diabetes and among obese women improves the severity of UI symptoms.27,29,30

Diabetes and vascular disease progression over time may have direct impact on UI and other LUTS as contributors to impaired bladder detrusor muscle function and control.31 Early in diabetes and in vascular disease states, decreases in blood flow may contribute to impaired detrusor muscle control, contributing to symptoms of overactive bladder and/or UI.32 However, declines in bladder structure and control in later stage diabetes and vascular disease can lead to both sensory and motor dysfunctions, with associated symptoms including underactive bladder, urinary retention and resulting incontinence.33 At the level of the lower urinary tract, increased detrusor muscle fibrosis, changes in innervation, neurotransmitter responsiveness and alterations in urethral composition and control may all contribute to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The complicated relationship of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and vascular disease to UI and other LUTS needs further exploration of mechanisms related to bladder functional changes over time, bi-directional relationships between disease and bladder symptoms, and the relationship of disease-specific interventions (such as weight loss and physical activity) on bladder function.

Among persons living with neurologic diseases, those with concomitant UI experience greater impairments in QOL and a larger economic burden compared to those without UI.34 Some common neurologic diseases that have increased rates of UI include Alzheimer dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, lumbar spinal stenosis, and motor neuron diseases. Depending on the location and the extent of the neurologic lesion(s), the type and severity of UI may vary.35 For example, suprapontine lesions may result in complete loss of voluntary bladder control from lack of sphincteric control despite a normal micturition reflex. Cervical lesions typically result in detrusor-external sphincter dyssynergia, while thoracolumbar lesions may be associated with detrusor overactivity (DO) or detrusor areflexia (DA) which contribute to LUTS, including UI. Sacral lesions are often associated with DA or detrusor underactivity (DU); however, loss of bladder compliance and DO are also possible. Not all patients with neurologic disease have bladder dysfunction and patients with UI may also have subtle neurologic factors contributing to bladder symptoms. Despite these generalizations, incomplete understanding of the relationship between the central nervous system and LUT contributes to the poor association of symptoms with function in the individual patient.

While there is ample evidence that many chronic diseases are risk factors for UI, much less is known about the associations among multi-morbidity, frailty, and UI. Multi-morbidity, frailty, and UI are highly prevalent among older adults and share similar clinical outcomes, such as increased rates of institutionalization, impaired quality of life, and mortality.20,36,37 Current evidence from observational studies, clinical cohort studies, and clinical trials suggests that frailty is common among older women with UI.38–40 While less is known about multi-morbidity prevalence among older adults with UI, older adults with multi-morbidity may be more likely to receive better overall quality of care.41 However, when older adults also experience common geriatric syndromes, such as UI, the quality of care declines.42 Treatment of UI in older adults with multi-morbidity and frailty is complicated by multiple factors from the patient and the provider perspective. These factors may include, but are not limited to, polypharmacy, drug-drug interactions, limited mobility, competing demands from disease burden, and cognitive decline. Few clinical trials or clinical practice guidelines include specific recommendations on the treatment of UI among older adults with multi-morbidity and frailty.40,43–45 Collection of data measuring multi-morbidity and frailty in existing longitudinal studies, clinical trials, and clinical care could inform the many existing gaps, guide clinical practice guidelines, and ultimately improve care.

Knowledge is lacking about the impact of upper urinary tract (kidneys and ureters) aging on LUT function (bladder and urethra). In general, the aging kidney impacts fluid balance through several mechanisms. Creatinine clearance may decline in older adults in the absence of known kidney disease and other comorbidities.46 Fluid balance is also affected through decreases in the aging kidney’s ability to respond to anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), leading to water loss and decreased urine osmolality.47 Sodium wasting may occur through decreased aldosterone levels in older adults. Through these physiologic changes that occur with age, older adults may also have increased rates of urine production at night via decreased rates of ADH secretion specifically at night and lower rates of atrial natriuretic hormone. Nocturnal polyuria is defined by more than a third of the 24-hour urine production occurring at night48. Predisposing factors for nocturnal polyuria include advanced age, chronic kidney disease, fluid shifts in extremity edema while recumbent, and osmotic diuresis. Diuretic-induced polyuria contributes to urinary symptoms, and may impact adherence to diuretic treatment.49 The intersection of increased urine production at night, nocturia, and impaired sleep represents an important area where more evidence to inform clinical practice guidelines are needed.

In addition to delirium and insomnia, falls and mobility problems are associated with increased rates of UI. One study suggested that urgency UI and stress UI are associated with decreased gait speed and balance.50 Another small study reported that bladder sensations of a strong desire to void may decrease gait speed and stride length in older women without UI.51 In other studies, nocturia with incontinence increased rates of falls.6 Presence of white matter hyperintensities within key brain regions overlapping with white matter tracts known to be involved in bladder control may be responsible for declines in mobility and micturition sensations.52 Once completed, the INFINITY (INtensive versus standard ambulatory blood pressure lowering to prevent functional DeclINe in the ElderlY) trial will demonstrate whether more intensive treatment of elevated blood pressure reduces white matter hyperintensities and decreases overall burden of disease while delaying functional declines in mobility and incontinence.53 Such trials targeting brain white matter hyperintensities could help inform future prevention studies addressing these and other shared risk factor pathways.

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of UI & Common pathways – Micro level

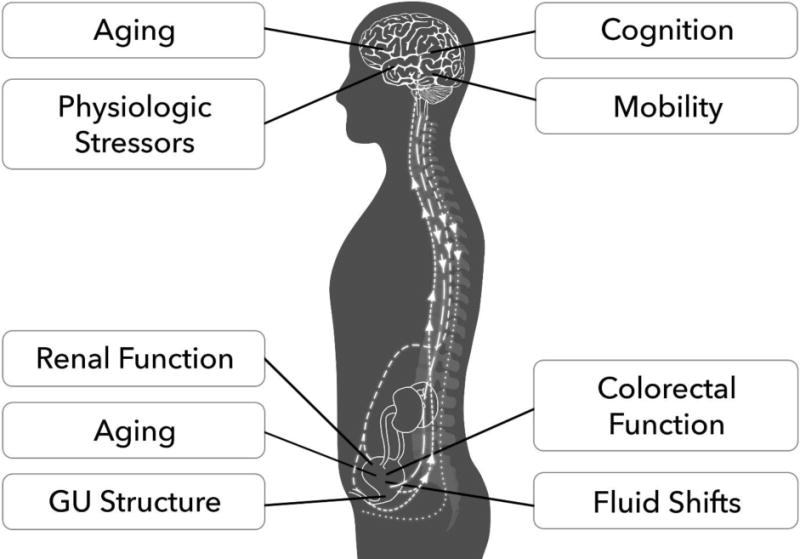

Control over urine storage and voiding is predicated on a series of carefully coordinated steps. These include accurate afferent information regarding bladder volume, the reception and integrative processing of this information within the central nervous system, ability to make appropriate decisions, a situationally appropriate efferent neural data stream, ability of end organs involved in LUT control (bladder, urethra, pelvic floor) and in mobility (brain, muscle, cardiovascular system) to respond, plus the ability to engage in socially appropriate toileting behavior (Figure 1, Video S1).

Figure 1. Factors Contributing to Urinary Continence in Older Adults.

Maintaining continence requires adaptive reserve within the bladder and pelvic tissue capabilities, central nervous system control networks, and perceptual processes within the individual’s social context. GU=Genitourinary; An interactive figure is available online as Supplemental Video S1.

The stream of afferent activity reporting on bladder capacity originates with the transduction of the mechanical stresses induced by bladder volume to an afferent nerve signal. The demonstrated linkage of afferent activity to volume-induced wall stresses54 and observations of bursts of bladder afferent activity accompanying small waves of pressure associated with non-voiding contractions55 are indicative of the relationship of bladder wall biomechanics to afferent responses to bladder volume. Tension in the bladder wall, and thus the relationship of afferent activity to volume, can vary from a minimal value established by the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the absence of muscle activity, to a maximum due to unsuppressed myocyte activity superimposed on the ECM56. Detrusor activity is normally suppressed by sympathetic autonomic input, placing afferent sensitivity to bladder volume under central control. The urothelium has been recognized as a contributor to bladder signaling, rather than acting simply as a passive barrier57. Published changes associated with aging of the urothelium include increases in the presence of inflammatory cells, P2X3 receptor expression, lipofuscin accumulation and markers of oxidative stress58–61. More recent findings presented (Birder et al., unpublished) regarding the urothelial extracellular matrix include loss of organization, collagen/elastin fiber breakage, thickening, and clumping, contributing to loss of elasticity and increased stiffness62. Collagen fibers within the mucosa (urothelium/lamina propria) are normally finer and more organized in a wavy distribution than the larger diameter fibers within the detrusor smooth muscle, and demonstrate different responses to stretch. These morphologic differences likely reflect functional differences involving mucosal as opposed to muscular responses to bladder distension.

The influence of aging on regulation of volume sensory transduction, transmission, reception and processing following the tension-induced initiation of the transduction cascade is incompletely understood.63 Sympathetic modulation of detrusor myocyte activity-induced tension points to the possibility of ongoing sympathetic-mediated central regulation over bladder volume sensitivity. Similar forward-feedback brain regulation over sensory input via end-organ control has been described in other systems such as hearing, permitting adaptive responses aimed at integrating sensory stressors with physiologic needs and capabilities. Indirect evidence (power spectral analysis of bladder pressure vs. volume waveforms) has suggested increasing influence of brain control over bladder volume sensitivity in an aging mouse cystometric model64. Although this could be a pathology of aging, the uniformity of both aging impact and effect within age groups suggests this could be an adaptive mechanism. Afferent signaling about bladder volume results in activation of the periaqueductal grey in the brainstem. White matter hyperintensity disease (WMD) is associated with loss of the prefrontal cortex (PFC)-periaqueductal grey (PAG) long tract connection, contributing to loss of voluntary control over storage vs. voiding. Loss of prefrontal inhibition of PAG could contribute to urge incontinence. Of interest is the finding that WMD disease burden in brain areas relevant to urinary control is associated with increased severity, but not necessarily prevalence of urinary symptoms52, pointing to the impact of WMD – and perhaps aging – on urinary perceptual processes as a contributor to symptom bother, possibly independent of objective functional changes.

While intimately involved in the relationship of bladder volume and afferent signaling, the structural and intramural regulatory systems of the bladder are involved with specific responses to efferent activity. Tension in the bladder wall due to chronically increased detrusor pressures and/or over-distended bladder volumes result in hypoperfusion, hypoxia, and activation of oxidative stress mechanisms. A lumbar central pattern generator (Lumbar Spinal Coordinating Center, LSCC) contributes to hindlimb control during locomotion in quadrupeds and is likely phylogenetically preserved in humans65. This same region communicates with bladder and the striated muscle component of the urinary sphincter mechanism (external urinary sphincter, EUS)63, and is therefore implicated in the reflexic relationship of bladder volume and voiding. During urine storage, these regions could contribute to detrusor inhibition/sphincter resistance to opening. As a pattern generator, this region could provide the pulsatile sphincteric action observed during voiding in some animal models (mouse, rat) and in dyssynergic human voiding observed in fetal life/infants, dysfunctional voiding in older adults, and in the extreme, neurologic injury/disease. The common feature in humans showing this pattern would appear to be loss of suppression related to prefrontal control over synergic pontine voiding, although this remains to be demonstrated. As a contributor to both impaired voluntary control and inefficient voiding, however, loss of normal control over this central pattern generator offers a possible contributor to incontinence in older adults.

Current and Emerging Treatment Modalities for UI

Behavioral therapy for UI encompasses a wide array of strategies including lifestyle modification, changes in voiding habits, and learning skills to maintain continence. Thus, behavioral therapy is inherently multicomponent and can be individualized depending on the most pertinent individual contributing conditions. Pelvic floor muscle exercise-based behavioral therapy for stress and urgency UI is well studied in women and men66,67. While there is growing evidence for behavioral therapy in populations with neurologic disease such as those with stroke, Parkinson disease, or multiple sclerosis, larger, controlled trials are needed45,68–70. Behavioral therapy requires that individuals maintain motivation and practice in order to achieve results, which typically occur gradually over several weeks. Evidence suggests patients achieve clinically significant reduction in urgency UI with a self-help booklet describing behavioral therapy, although many patients perceive greater improvement after receiving instruction from a clinician67.

Despite the recommendation that behavioral therapy be the initial treatment approach for UI, many patients are not offered treatments. Barriers to broad implementation of behavioral treatments include lack of provider knowledge of behavioral principles and techniques and a viable reimbursement mechanism for the time needed to teach the behavioral skills. Thus, future research goals include optimizing behavioral training for UI to augment long-term efficacy and improving implementation, in order to offer behavioral therapy more broadly. Several studies have evaluated alternate delivery methods to provide behavioral therapy to treat UI including self-help booklets, internet-based training, and group classes71–73. UI is usually part of a constellation of urinary symptoms suffered by the individual. The symptom complex of urgency (with or without incontinence), identified as OAB74, has been equated with inappropriate detrusor-driven bladder pressurization (detrusor overactivity, DO). More recently, symptoms of impaired voiding have been identified as “underactive bladder (UAB)75, analogously suggestive of insufficient detrusor-driven bladder pressure. These etiologic models have contributed to the pursuit of therapies aimed at correcting detrusor dysfunction. For OAB, these initially took the form of nonspecific anticholinergic agents, and in more recent decades, agents aimed at bladder-specific muscarinic M3 receptors76. A significant problem with this etiologic model is the lack of clear interdependence between symptoms (OAB, UAB) and function (DO, DU) demonstrated during urodynamic assessment77–83. An emerging therapeutic model, which may be particularly relevant for older adults, addresses abnormal generation of bladder volume sensory afferent activity, due to either abnormal focal tensions in the bladder wall and/or activation of atypical sensory pathways as an etiologic pathway for urinary storage symptoms such as OAB and UAB84–87.

New therapeutic targets for OAB symptoms include the urothelium, detrusor, and spinal signaling. Targets of recent investigations have included phosphodiesterase inhibition, purinergic receptors, potassium channel openers, the cannabinoid system, spinal signaling (e.g. gabapentin), and transient receptor potential (TRP) V1 channel antagonists. Antagonists of the purinergic P2X3 receptor, which are involved in bladder afferent signaling, result in larger voided volumes with decreased urinary frequency in a rodent model.

PDE5 inhibitors, FDA approved for erectile dysfunction, have been associated with improved lower urinary tract symptoms in men using these agents for their approved purpose88–90. Inhibition of fatty acid amine hydrolase, which is a cannabinoid degrading enzyme, similarly lead to depressed bladder afferent signaling with an increase in bladder capacity91. Inhibition of aberrant (c-fiber) bladder afferent-induced spinal signaling with gabapentin has been tested in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients, but has not been formally evaluated for symptoms of incontinence in the non-SCI population92. A previous study of cannabis in multiple sclerosis patients suggested a reduction in urgency UI compared to placebo although there were no differences in the primary outcome of spasticity93. TRP channels are found in urothelial cells, bladder afferent nerves, and detrusor smooth muscle cells. An antagonist of TRPV1 receptors found on substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide containing nerves suppressed capsaicin-induced increase in nerve discharge and intravesical pressure without affecting voided volume or maximal voiding pressure in a rodent model94. However, a phase I clinical trial in humans showed a mean increase in body temperature of up to 1.3° F with the highest administered dose95.

Medication-based approaches to influence central control of bladder function thus far have resulted in low efficacy or unacceptable side effects such as sedation. Currently there are no pharmacologic treatments for UAB. Functional phenotyping of patients with OAB/UAB/UI, aimed at establishing mechanisms of pathophysiology, may reveal strategies for personalized therapy or combination therapy aimed at optimizing treatment goals and minimizing side effects.

Third line treatments for OAB and UI include neuromodulation and chemodenervation. Implantable sacral neuromodulation has been available for refractory urgency UI since 1998, FDA approved for urgency, urge incontinence, and urinary retention. The exact mechanism of action is unknown; however, stimulation of the S3 nerve root is thought to reduce bladder afferent signaling and increase relaxation of bladder smooth muscle. While use in older patients has increased, younger populations are still more likely to receive an implantable stimulator. In one long-term study of Medicare recipients over 10 years, 11% of patients opted for explantation of the device over a mean follow-up period of 60 months96. Cohort studies have not shown age-dependent differences in efficacy of implantable neuromodulation97. Studies in patients with neurologic disease such as Parkinson disease, stroke and multiple sclerosis, have shown mixed results.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) was approved in 2000 for urgency UI and is now approved for use in refractory overactive bladder. Because PTNS is minimally invasive and can be administered in an outpatient setting, it may be more feasible in an older population with multiple chronic conditions. Small studies also suggest potential efficacy in older adults with neurologic disease98 or those in residential care99.

A recent study compared acupuncture to tolterodine for overactive bladder symptoms in women and showed similar improvements between the groups at 4 weeks, although longer term studies are needed100. Chemodenervation with onobotulinum toxin A has been FDA-approved for overactive bladder symptoms since 2013. Onobotulinum toxin is presumed to block presynaptic release of acetylcholine leading to irreversible relaxation of bladder smooth muscle until the toxin is cleared (typically about 6 months). There is increased risk of requiring clean intermittent catheterization after the procedure in persons who have urinary retention at baseline. Ultimately, with all of these approaches, shared decision making is important to develop a treatment strategy that aligns with patient preferences and goals of care.

For most geriatric syndromes, single intervention studies are typically less effective, whereas evidence supports multicomponent interventions to reduce incident disease101,102. Especially in light of the evidence regarding the association of mobility impairment and changes in neural control of bladder function with incontinence, the development of novel multicomponent interventions for older adults with multi-morbidity and UI deserves renewed attention50,52,103. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy is one published strategy for optimizing multicomponent interventions, while gaining understanding of single intervention components prior to a randomized controlled trial104. A team science approach with input from multiple disciplines including behavioral scientists and implementation science experts may facilitate development of multicomponent interventions more rapidly.

From Bench to Bedside and Beyond

In addition to discussion of research priorities focused on better treatments, attendees also discussed the urgent need to develop strategies to disseminate existing evidence broadly to the community. Evidence-based practice change models are available to guide best practices for the implementation and dissemination of new models for continence care105–107. These models often begin with a practice change leader who creates a sense of urgency about the clinical problem and engaging multiple stakeholders to partner in developing a solution108,109. Determination of the core components of a successful quality improvement program is necessary in order to allow for adaptation and facilitate dissemination110.

Investigators have also begun to evaluate the delivery of behavioral therapy to prevent lower urinary tract symptoms for populations at risk of developing UI. One study evaluated a single pre-operative visit to teach pelvic floor muscle-based behavioral therapy for continent men preparing to undergo radical prostatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate and showed only 5 men needed to be treated in order for at least one to achieve post-prostatectomy continence111. Other studies have evaluated group therapy models either in the clinical setting or in community-based settings as preventive strategies for incident UI112,113.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Ultimately, several overarching research themes were generated during conference planning, presentations and related discussions. Table 1 includes recommendations and ideas for future research directions that were subsequently synthesized and prioritized. Supplementary Appendix S2 includes broader discussion of each of the research priorities.

Table 1.

Recommendations for Future Research Priorities and Direction

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Regulatory Pathways and Resilience (causes, mechanisms, and pathways) | Defining how aging and specific chronic diseases influence resilience - the ability of regulatory pathways to maintain lower urinary tract homeostasis, normal voiding and continence in the older adults when challenged with common stressors (e.g. bladder filling, ischemia, oxidative stress, infection, altered microbiome) |

| Linkages with other Geriatric Syndromes (relationships among syndromes) | Bidirectional relationships between urinary incontinence and other geriatric syndromes at the level of shared risk factors/mechanisms or responses to treatment |

| Designing Effective Treatments (translation and testing) | Overcoming obstacles to the design and testing of single and multi-component interventions |

| Individualizing Treatment Approaches | Targeting specific treatments to define subpopulation of patients with voiding disorders or incontinence (e.g. Precision Medicine) |

| Help-Seeking and Uptake of Conservative Treatments (implementation and T2 translation issues) | Overcoming barriers to incontinence diagnosis, as well as dissemination and implementation of relevant science |

| Continence Promotion and LUTS Prevention (predictors, progression, and prevention) | Develop a deeper understanding of the potentially modifiable factors involving the patient, caregiver or environment that contribute to an enhanced risk of incontinence in late life |

| Design and Methods Considerations | Promote the inclusion of secondary outcome measures pertaining to incontinence in large epidemiological studies and clinical trials, through the advancement of relevant research methods and addition of genitourinary parameters to NIH Toolbox |

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1: Writing Group, Planning Committee, Presenter List.

Supplementary Appendix S2: Research Priorities Emerging from AGS/NIA U13 Bench-to-Bedside Conference on Urinary Incontinence in Older Adults.

Supplemental Video S1: Video of the interactive version of Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

Jerry Blaivas

Employment or Affiliation: Co-Founder, Board Member and Chief Scientific Officer of Symptelligence, LLC a medical informatics company that develops software and owns patents relating to lower urinary tract symptoms incontinence diagnosis, clinical decision making and phenotyping.

Patents: Co-founder, board member and chief scientific officer of Symptelligence, LLC a medical informatics company that develops software and owns patents relating to lower urinary tract symptoms incontinence diagnosis, clinical decision making and phenotyping.

Kathryn Burgio

Grants/Funds: I have grant funding from the National Institute on Aging.

William C. de Groat

Grants/Funds: Research Contract from the Astellas Pharmaceutical Company to conduct animal research.

Consultant: For Bayer Pharma AG, NeuSpera Medical and Amphora Medical.

Catherine DuBeau

Honoraria: AGS Beers Criteria Review Panel

Ariel Green

Grants/Funds: I’m a co-investigator on grants that receive funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Tomas Griebling

Grants/Funds: I receive grant funding through the National Institute on Aging, and the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation. Neither are directly associated with my work on this project.

Derek Griffiths

Employment or Affiliation: Occasional consulting for University of Pittsburgh

Consultant: Occasional consulting for Laborie Medical

Alison Huang

Grants/Funds: I have research grants from Pfizer, Inc. awarded through the University of California San Francisco to conduct research unrelated to this material.

Theodore Johnson

Consultant: Consultant within the past 3 years for Astellas (unrestricted CME, use of mirabegron in older adults), Medtronic (UI treatment in LTC), Vantia (development of QoL instrument for nocturia)

John Lavelle

Consultant: Member Scientific Advisory Board Dignify Therapeutics. Subject of talk at the meeting did not refer to this, as product not relevant to artificial urinary sphincters.

Stocks: Member Scientific Advisory Board Dignify Therapeutics. Subject of talk at the meeting did not refer to this, as product not relevant to artificial urinary sphincters.

Alayne Markland

Grants/Funds: NIH Grant U01DK106858 and Department of Veterans Affairs funding

Neil Resnick

Grants/Funds: NIH grant funding to investigate incontinence since 1982.

Marcel Salive

Employment or Affiliation: I am an employee of the National Institute on Aging/NIH, which provided a grant for the conference. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Phillip Smith

Employment or Affiliation: I am employed by the State of Connecticut/University of Connecticut. The views and opinions expressed in my contribution to this manuscript are my own and may not reflect the views and priorities of my employer. Publication of this manuscript will favorably impact my CV and contribute to a positive relationship with my employer.

Grants/Funding: My research is funded by both an institutional grant and by NIH/NIA 5K76AG054777-02. Similarly, the views and opinions expressed in my contribution to this manuscript are my own and may not reflect the views and priorities of these agencies. Publication of this manuscript will favorably impact my CV and contribute to success in achieving continued NIH funding for my research.

Camille Vaughan

Personal Relationship: Spouse is a full-time employee of Kimberly-Clark Corp.

Adrian Wagg

Grants/Funds, Honoraria, Speaker Forum, and Consultant: Monies received either personally or for my institution for any of research grants, participation, speaker honoraria or consultancy from: Astellas, Pharma Pfizer Corp, SCA AB

Jean Wyman

Grants/Funds: Salary support by NIDDK/NIH grant

The NIA funded this conference (NIA 5U13AG0-39151–02). Additional funding for the conference was provided by Allergan, Astellas, and Medtronic. We thank Marie A. Bernard, PhD, Nancy Lundebjerg, MPA, Francesca Macchiarini, MS, PhD, and all conference participants. We appreciate the excellent administrative support provided by Anna Mikhailovich and Alanna Goldstein, MPH, and the detailed program evaluation provided by Julie Robison, PhD. Views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or other affiliated organizations.

Conflict of Interest

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

*Author

1 Peter Abadir |

Author

2 Karl-Erik Andersson |

Author

3 Tamara Bavendam |

Author

4 Lori Birder |

Author

5 Jerry Blaivas |

Author

6 Kathryn Burgio |

Author

7 William C. de Groat |

|||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

*Author

8 Ananias Diokno |

Author

9 Catherine DuBeau |

Author

10 Matthew Fraser |

Author

11 Patricia Goode |

Author

12 Ariel Green |

Author

13 Tomas Griebling |

Author

14 Derek Griffiths |

|||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

Author

15 Francine Grodstein |

Author

16 Rasheeda Hall |

Author

17 Alison Huang |

Author

18 Theodore Johnson |

Author

19 George Kuchel |

Author

20 John Lavelle |

Author

21 Alayne Markland |

|||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

Author

22 Mary H. Palmer |

Author

23 Neil Resnick |

Author

24 Marcel Salive |

Author

25 Phillip Smith |

Author

26 Stephanie Studenski |

Author

27 Camille Vaughan |

Author

28 Adrian Wagg |

|||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts |

Author

29 Leslie Wolfson |

Author

30 Jean Wyman |

||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Consultant | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Stocks | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Royalties | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Board Member | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Patents | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| * Authors can be listed by abbreviations of their names. | ||||||||||||||

| For all “Yes” responses provide a brief explanation here: | ||||||||||||||

The following individuals do not have a conflict of interest:

Peter Abadir

Karl-Erik Andersson

Tamara Bavendam

Lori Birder

Ananias Diokno

Matthew Fraser

Patricia Goode

Francine Grodstein

Rasheeda Hall

George Kuchel

Mary H. Palmer

Stephanie Studenski

Leslie Wolfson

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to this paper.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and Trends of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in U.S. Women. Obstetr Gynecol. 2014;123(1):141–148. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diokno AC, Estanol MVC, Ibrahim IA, Balasubramaniam M. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in community dwelling men: a cross sectional nationwide epidemiological survey. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39(1):129–136. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-9127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouslander JG, Kane RL, Abrass IB. Urinary incontinence in elderly nursing home patients. JAMA. 1982;248(10):1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adelmann PK. Prevalence and detection of urinary incontinence among older Medicaid recipients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;15.1:99–112. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2004.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin EB, Buehler AE, Halpern SD. States worse than death among hospitalized patients with serious illnesses. JAMA Int Med. 2016;176(10):1557–1559. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiarelli PE, Mackenzie LA, Osmotherly PG. Urinary incontinence is associated with an increase in falls: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55(2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(09)70038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felde G, Ebbesen MH, Hunskaar S. Anxiety and depression associated with urinary incontinence. A 10-year follow-up study from the Norwegian HUNT study (EPINCONT) Neurourol Urodyn. 2015 doi: 10.1002/nau.22921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimby A, Milsom I, Molander U, Wiklund I, Ekelund P. The influence of urinary incontinence on the quality of life of elderly women. Age Ageing. 1993;22(2):82–89. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.2.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman SM, Steinwachs DM, Rathouz PJ, Burton LC, Mukamel DB. Characteristics Predicting Nursing Home Admission in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for Elderly People. Gerontologist. 2005;45(2):157–166. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König H-H, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric Syndromes: Clinical, Research, and Policy Implications of a Core Geriatric Concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgio KL, Ives DG, Locher JL, Arena VC, Kuller LH. Treatment seeking for urinary incontinence in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(2):208–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waetjen LE, Xing G, Johnson WO, Melnikow J, Gold EB. Factors associated with seeking treatment for urinary incontinence during the menopausal transition. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Rhodes T, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community-based cohort: prevalence and healthcare-seeking. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(4):467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox C, Smith T, Maidment I, et al. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):604–615. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeitzer JM, Bliwise DL, Hernandez BA, Friedman L, Yesavage J. Nocturia compounds nocturnal wakefulness in older individuals with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(3):259–262. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araujo AB, Yaggi HK, Yang M, McVary KT, Fang SC, Bliwise DL. Sleep-related problems and urologic symptoms: Testing the hypothesis of bi-directionality in a longitudinal, population-based study. J Urol. 2014;191(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endeshaw YW, Johnson TM, Kutner MH, Ouslander JG, Bliwise DL. Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Nocturia in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):957–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pressman MR, Figueroa WG, Kendrick-Mohamed J, Greenspon LW, Peterson DD. Nocturia: A rarely recognized symptom of sleep apnea and other occult sleep disorders. Arch Int Med. 1996;156(5):545–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Comorbidities and personal burden of urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(10):1015–1033. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han TS, Tajar A, Lean ME. Obesity and weight management in the elderly. Br Med Bull. 2011;97:169–196. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denys MA, Anding R, Tubaro A, Abrams P, Everaert K. Lower urinary tract symptoms and metabolic disorders: ICI-RS 2014. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(2):278–282. doi: 10.1002/nau.22765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunn F, Kirby M, Pinkney E, et al. Is there a link between overactive bladder and the metabolic syndrome in women? A systematic review of observational studies. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(2):199–217. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu A, Conell-Price J, Stijacic Cenzer I, et al. Predictors of urinary incontinence in community-dwelling frail older adults with diabetes mellitus in a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Karter AJ, Thai JN, Van Den Eeden SK, Huang ES. Glycemic control and urinary incontinence in women with diabetes mellitus. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(12):1049–1055. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):481–490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subak LL, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Urinary Incontinence Before and After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Int Med. 2015;175(8):1378–1387. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vissers D, Neels H, Vermandel A, et al. The effect of non-surgical weight loss interventions on urinary incontinence in overweight women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15(7):610–617. doi: 10.1111/obr.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan S, Kanaya AM, Subak LL, et al. Weight loss prevents urinary incontinence in women with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial. J Urol. 2012;187(3):939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu S, Tsounapi P, Shimizu T, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms, benign prostatic hyperplasia/benign prostatic enlargement and erectile dysfunction: are these conditions related to vascular dysfunction? Int J Urol. 2014;21(9):856–864. doi: 10.1111/iju.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomiya M, Andersson KE, Yamaguchi O. Chronic bladder ischemia and oxidative stress: new pharmacotherapeutic targets for lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Urol. 2015;22(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/iju.12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto S, Kakizaki H. Causative significance of bladder blood flow in lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Urol. 2012;19(1):20–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2011.02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tapia CI, Khalaf K, Berenson K, Globe D, Chancellor M, Carr LK. Health-related quality of life and economic impact of urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity associated with a neurologic condition: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drake MJ, Apostolidis A, Cocci A, et al. Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: Clinical management recommendations of the Neurologic Incontinence committee of the fifth International Consultation on Incontinence 2013. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(6):657–665. doi: 10.1002/nau.23027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):719–736. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erekson EA, Ciarleglio MM, Hanissian PD, Strohbehn K, Bynum JP, Fried TR. Functional disability and compromised mobility among older women with urinary incontinence. Female Pelv Med Reconstruct Surg. 2015;21(3):170–175. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miles TP, Palmer RF, Espino DV, Mouton CP, Lichtenstein MJ, Markides KS. New-onset incontinence and markers of frailty: data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Gerontol Ser A-Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Jan;56(1):M19–24. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.1.m19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubeau CE, Kraus SR, Griebling TL, et al. Effect of fesoterodine in vulnerable elderly subjects with urgency incontinence: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2014;191(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Min LC, Wenger NS, Fung C, et al. Multimorbidity is associated with better quality of care among vulnerable elders. Med Care. 2007;45(6):480–488. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318030fff9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min L, Kerr EA, Blaum CS, Reuben D, Cigolle C, Wenger N. Contrasting effects of geriatric versus general medical multimorbidity on quality of ambulatory care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1714–1721. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagg A, Gibson W, Ostaszkiewicz J, et al. Urinary incontinence in frail elderly persons: Report from the 5th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014 doi: 10.1002/nau.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s, Children’s Health. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Urinary Incontinence in Women: The Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (UK); 2013. Copyright (c) 2013 National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6, Supplement):2455–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glassock RJ, Denic A, Rule AD. The conundrums of chronic kidney disease and aging. J Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40620-016-0362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sands JM. Urine concentrating and diluting ability during aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(12):1352–1357. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Chaikin D, et al. The standardisation of terminology in nocturia: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nau.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel M, Vellanki K, Leehey DJ, et al. Urinary incontinence and diuretic avoidance among adults with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(8):1321–1326. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fritel X, Lachal L, Cassou B, Fauconnier A, Dargent-Molina P. Mobility impairment is associated with urge but not stress urinary incontinence in community-dwelling older women: results from the Ossébo study. BJOG. 2013;120(12):1566–1574. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Booth J, Paul L, Rafferty D, Macinnes C. The relationship between urinary bladder control and gait in women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32(1):43–47. doi: 10.1002/nau.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuchel GA, Moscufo N, Guttmann CR, et al. Localization of brain white matter hyperintensities and urinary incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(8):902–909. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White WB, Marfatia R, Schmidt J, et al. INtensive versus Standard Ambulatory Blood Pressure Lowering to Prevent Functional DeclINe In The ElderlY (INFINITY) Am Heart J. 2013;165(3):258–265.e251. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.le Feber J, van Asselt E, van Mastrigt R. Afferent bladder nerve activity in the rat: a mechanism for starting and stopping voiding contractions. Urolog Res. 2004;32(6):395–405. doi: 10.1007/s00240-004-0416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heppner TJ, Tykocki NR, Hill-Eubanks D, Nelson MT. Transient contractions of urinary bladder smooth muscle are drivers of afferent nerve activity during filling. J Gen Physiol. 2016;147(4):323–335. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coolsaet B. Bladder compliance and detrusor activity during the collection phase. Neurourol Urodyn. 1985;4(4):263–273. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birder LA. Urothelial signaling. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153(1–2):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phillips JI. Inflammatory plasma cell infiltration of the urinary bladder in the aging C57BL/Icrfa(t) mouse. Investigat Urol. 1981;19(2):75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perse M, Injac R, Erman A. Oxidative status and lipofuscin accumulation in urothelial cells of bladder in aging mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nocchi L, Daly DM, Chapple C, Grundy D. Induction of oxidative stress causes functional alterations in mouse urothelium via a TRPM8-mediated mechanism: implications for aging. Aging cell. 2014;13(3):540–550. doi: 10.1111/acel.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daly DM, Nocchi L, Liaskos M, McKay NG, Chapple C, Grundy D. Age-related changes in afferent pathways and urothelial function in the male mouse bladder. J Physiol. 2014;592(3):537–549. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.262634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kullmann FA, Birder LA, Andersson K-E. Translational Research and Functional Changes in Voiding Function in Older Adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(4):535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Groat WC, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N. Neural control of the lower urinary tract. Compr Physiol. 2015;5(1):327–396. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith PP, DeAngelis A, Simon R. Evidence of increased centrally enhanced bladder compliance with ageing in a mouse model. BJU Int. 2015;115(2):322–329. doi: 10.1111/bju.12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dietz V. Do human bipeds use quadrupedal coordination? Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(9):462–467. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(23):1995–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al. Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(18):2293–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaughan CP, Juncos JL, Burgio KL, Goode PS, Wolf RA, Johnson TM., 2nd Behavioral therapy to treat urinary incontinence in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2011;76(19):1631–1634. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318219fab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucio AC, Campos RM, Perissinotto MC, Miyaoka R, Damasceno BP, D’Ancona CA. Pelvic floor muscle training in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction in women with multiple sclerosis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(8):1410–1413. doi: 10.1002/nau.20941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tibaek S, Gard G, Jensen R. Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in women with urinary incontinence after stroke: a randomised, controlled and blinded study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(4):348–357. doi: 10.1002/nau.20134. [erratum appears in Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27(1):100] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus S, Thorpe K, Davis DA, Schmaltz H, Tannenbaum C. Translation of evidence into a self-management tool for use by women with urinary incontinence. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):227–233. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sjöström M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, Carlbring P, Andersson G, Samuelsson E. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: 1- and 2-year results of a randomized controlled trial with a focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int. 2015;116(6):955–964. doi: 10.1111/bju.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dugan SA, Lavender MD, Hebert-Beirne J, Brubaker L. A Pelvic Floor Fitness Program for Older Women With Urinary Symptoms: A Feasibility Study. PM&R. 2013;5(8):672–676. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21(2):167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chapple CR, Osman NI, Birder L, et al. The Underactive Bladder: A New Clinical Concept? Eur Urol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCrery RJ, Smith PP, Appell RA. The emergence of new drugs for overactive bladder. Expert Opin Emer Drugs. 2006;11(1):125–136. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Flisser AJ, Blaivas JG. Role of cystometry in evaluating patients with overactive bladder. Urology. 2002;60(5 Suppl 1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01791-0. discussion 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guralnick M, Grimsby G, Liss M, Szabo A, O’Connor R. Objective differences between overactive bladder patients with and without urodynamically proven detrusor overactivity. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(3):325–329. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hashim H, Abrams P. Is the bladder a reliable witness for predicting detrusor overactivity? J Urol. 2006;175(1):191–194. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00067-4. discussion 194–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jeong SJ, Kim HJ, Lee YJ, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Features of Detrusor Underactivity among Elderly with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Comparison between Men and Women. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(5):342–348. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Resnick NM, Yalla SV, Laurino E. The pathophysiology of urinary incontinence among institutionalized elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(1):1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vecchioli-Scaldazza C, Grinta R. Overactive bladder syndrome: what is the role of evidence of detrusor overactivity in the cystometric study? Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2010;62(4):355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith PP, Pregenzer G, Galffy A, Kuchel GA. Underactive bladder and detrusor underactivity represent different facets of volume hyposensitivity and not impaired contractility. Bladder. 2015;2(2):e17. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drake MJ, Kanai A, Bijos DA, et al. The potential role of unregulated autonomous bladder micromotions in urinary storage and voiding dysfunction; overactive bladder and detrusor underactivity. BJU Int. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bju.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fowler CJ. Bladder afferents and their role in the overactive bladder. Urology. 2002;59(5 Suppl 1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01544-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tadic SD, Griffiths D, Schaefer W, Resnick NM. Abnormal connections in the supraspinal bladder control network in women with urge urinary incontinence. NeuroImage. 2008;39(4):1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vahabi B, Drake MJ. Physiological and pathophysiological implications of micromotion activity in urinary bladder function. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015;213(2):360–370. doi: 10.1111/apha.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giuliano F, Uckert S, Maggi M, Birder L, Kissel J, Viktrup L. The mechanism of action of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2013;63(3):506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park HJ, Won JE, Sorsaburu S, Rivera PD, Lee SW. Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS/BPH with Erectile Dysfunction in Asian Men: A Systematic Review Focusing on Tadalafil. World J Mens Health. 2013;31(3):193–207. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2013.31.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oelke M, Wagg A, Takita Y, Büttner H, Viktrup L. Efficacy and safety of tadalafil 5 mg once daily in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia in men aged ≥75 years: integrated analyses of pooled data from multinational, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies. BJU Int. 2017;119(5):793–803. doi: 10.1111/bju.13744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aizawa N, Hedlund P, Füllhase C, Ito H, Homma Y, Igawa Y. Inhibition of Peripheral FAAH Depresses Activities of Bladder Mechanosensitive Nerve Fibers of the Rat. J Urol. 2014;192(3):956–963. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carbone A, Palleschi G, Conte A, et al. Gabapentin treatment of neurogenic overactive bladder. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29(4):206–214. doi: 10.1097/01.WNF.0000228174.08885.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Freeman RM, Adekanmi O, Waterfield MR, Waterfield AE, Wright D, Zajicek J. The effect of cannabis on urge incontinence in patients with multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled trial (CAMS-LUTS) Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17(6):636–641. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kitagawa Y, Wada M, Kanehisa T, et al. JTS-653 Blocks Afferent Nerve Firing and Attenuates Bladder Overactivity Without Affecting Normal Voiding Function. J Urol. 2013;189(3):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Round P, Priestley A, Robinson J. An investigation of the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel TRPV1 antagonist XEN-D0501 in healthy subjects. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(6):921–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cameron AP, Anger JT, Madison R, Saigal CS, Clemens JQ, the Urologic Diseases in America P Battery explantation after sacral neuromodulation in the medicare population. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32(3):238–241. doi: 10.1002/nau.22294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Peters KM, Killinger KA, Gilleran J, Boura JA. Does patient age impact outcomes of neuromodulation? Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32(1):30–36. doi: 10.1002/nau.22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kabay S, Canbaz Kabay S, Cetiner M, et al. The Clinical and Urodynamic Results of Percutaneous Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation on Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Urology. 2016;87:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Booth J, Hagen S, McClurg D, et al. A Feasibility Study of Transcutaneous Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation for Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction in Elderly Adults in Residential Care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(4):270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yuan Z, He C, Yan S, Huang D, Wang H, Tang W. Acupuncture for overactive bladder in female adult: a randomized controlled trial. World J Urol. 2015;33(9):1303–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inouye SK, Bogardus STJ, Charpentier PA, et al. A Multicomponent Intervention to Prevent Delirium in Hospitalized Older Patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, et al. A Multifactorial Intervention to Reduce the Risk of Falling among Elderly People Living in the Community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(13):821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.AuYong N, Lu DC. Neuromodulation of the Lumbar Spinal Locomotor Circuit. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2014;25(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Nair VN, Strecher VJ. A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(1):65–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Feldman PH, Kane RL. Strengthening Research to Improve the Practice and Management of Long-Term Care. Milbank Q. 2003;81(2):179–220. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lobach DF, Sanders GD, Bright TJ, et al. In: Enabling health care decisionmaking through clinical decision support and knowledge management. AHRQ, editor. Rockville, MD: 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fink H, Kuskowski M, Taylor B, et al. Association of Parkinson’s disease with accelerated bone loss, fractures and mortality in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(9):1277–1282. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, et al. Facilitators of Transforming Primary Care: A Look Under the Hood at Practice Leadership. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S27–S33. doi: 10.1370/afm.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kotter J. Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harv Bus Rev. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 110.Etheridge F, Couturier Y, Denis JL, Tremblay L, Tannenbaum C. Explaining the Success or Failure of Quality Improvement Initiatives in Long-Term Care Organizations From a Dynamic Perspective. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;33:672–689. doi: 10.1177/0733464813492582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Urban DA, et al. Preoperative Biofeedback Assisted Behavioral Training to Decrease Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Urol. 2006;175(1):196–201. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Diokno AC, Sampselle CM, Herzog AR, et al. Prevention of Urinary Incontinence by Behavioral Modification Program: A Randomized, Controlled Trial Among Older Women in the Community. J Urol. 2004;171(3):1165–1171. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000111503.73803.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tannenbaum C, Agnew R, Benedetti A, Thomas D, van den Heuvel E. Effectiveness of continence promotion for older women via community organisations: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, Al-Samarrai NR, Beck JC, Ouslander JG. Translating Clinical Research into Practice: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Exercise and Incontinence Care with Nursing Home Residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(9):1476–1483. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1: Writing Group, Planning Committee, Presenter List.

Supplementary Appendix S2: Research Priorities Emerging from AGS/NIA U13 Bench-to-Bedside Conference on Urinary Incontinence in Older Adults.

Supplemental Video S1: Video of the interactive version of Figure 1.