Abstract

This paper advances research on racism and health by presenting a conceptual model that delineates pathways linking policing practices to HIV vulnerability among Black men who have sex with men in the urban USA. Pathways include perceived discrimination based on race, sexuality and gender performance, mental health, and condom-carrying behaviors. The model, intended to stimulate future empirical work, is based on a review of the literature and on ethnographic data collected in 2014 in New York City. This paper contributes to a growing body of work that examines policing practices as drivers of racial health disparities extending far beyond violence-related deaths.

Keywords: Policing practices, HIV, BMSM, Racial health disparities

Introduction

HIV in the United States (US) disproportionately affects racial and sexual minority men. Of all HIV diagnoses among MSM in 2015, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) accounted for the largest proportion (39%), followed by White MSM (WMSM) (29%) and Latino MSM (27%) [1]. HIV diagnoses among young BMSM in the US have increased by 87% in the last decade [1]. A variety of social and structural factors drive BMSM’s vulnerability to HIV. These include income, education, and unemployment [2]—all factors which are also associated with residential segregation, concentrating BMSM in neighborhoods with high baseline HIV prevalence and affecting patterns of sexual partnering [2]. Additional structural and social drivers of BMSM’s vulnerability to HIV include stigma and homophobia [3] and access to HIV care [4].

Analyses of disparities in police stops and arrests show racially discriminatory policing practices to be an enduring feature of people of colors’ daily lives across the US [5–7]. Between 1995 and 2005, Blacks comprised approximately 13% of illicit drug users, but 36% of drug-related arrests and 46% of drug-related convictions [8]. In 2015, the national rate of lifetime illicit drug use among adults (18+) was 55.8% among Whites and 50% among Blacks [9], yet the imprisonment rate for drug charges was approximately six times higher among Blacks than that of Whites [10]. In New York City (NYC) in 2014, Black men under 16 were 17.3 times more likely to be arrested for a misdemeanor than their White counterparts [5]. Between 2008 and 2011, the New York Police Department issued eight citations for riding bicycles on sidewalks in the predominantly White neighborhood of Park Slope; in the nearby predominantly Black and Latino Bedford-Stuyvesant, they issued 2050 [7].

The Black Lives Matter movement has focused public health’s attention on the contribution of policing practices to racial health disparities [11]. One study of excessive police violence estimated that Black men are 21 times more likely to be killed by police than White men [12]. Death caused by an active-duty law enforcement officer was the third leading cause of violence-related death across 16 US states in 2006 [13]. During the same period, deaths caused by law enforcement were four times higher among non-Hispanic Black males than those among non-Hispanic White males [13].

The health impact of policing practices, however, extends beyond the direct injury and mortality caused by police violence. Policing practices such as stop and frisk, intrusive searches, misdemeanor arrests, and arrests without probable cause are all part of “zero tolerance” approach which incentivizes police to increase their stops, searches, and arrests [14]. A small but growing body of evidence suggests that the targeting of Black men in this “zero tolerance” approach [15] may drive racial health disparities across multiple outcomes including obesity and diabetes [16], trauma and anxiety [17], and stress [18]. Research on policing practices in relation to HIV, however, has primarily focused on sex workers and intravenous drug users (IDUs) [19] and has identified associations between policing practices and HIV risk behaviors such needle-sharing and rushed injections [19]. No US-based studies have examined how policing practices shape HIV vulnerability for BMSM.

To address this gap, we developed a model that conceptualizes the pathways through which policing practices drive BMSM’s HIV vulnerability. Building on a long tradition within HIV research that has documented how structural factors such as racism and sexual oppression drive HIV, this paper operationalizes racism as a social determinant of HIV for BMSM. The model is intended to stimulate further research into the pathways we describe. Therefore, some pathways are suggestive rather than conclusive. The goal of this paper is to synthesize knowledge about how policing practices shape HIV vulnerability for BMSM and to identify pathways for future research.

Methods

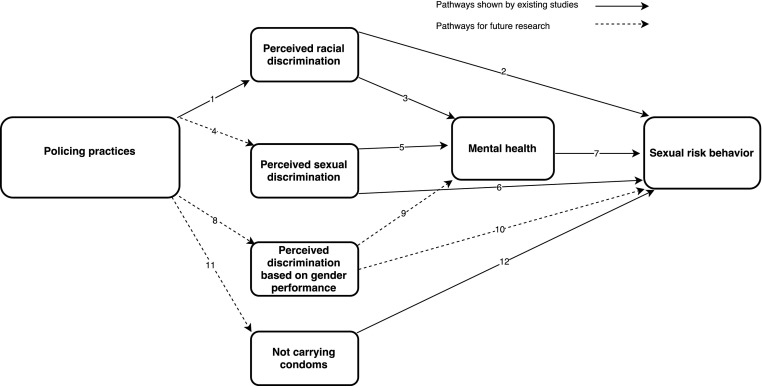

The conceptual model was developed using a literature review and also ethnographic data collected in 2014, described next. The ethnographic study focused on community-level determinants of HIV vulnerability for BMSM but did not focus specifically on policing practices as a driver of HIV vulnerability. Therefore, the ethnographic data presented here are limited in scope, primarily illustrative of specific pathways that emerged from the literature review. In some instances, we use the ethnographic findings to suggest potential pathways that have not yet been examined by research. Pathways that require further research are labeled as such (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathways between policing practices and BMSM’s HIV vulnerability

Literature Review

Our literature review followed a two-step process. First, we identified social determinants of HIV among racial and sexual minorities. We did so using peer-reviewed studies [20, 21] and meta-analyses [22]. Since few peer-reviewed studies directly examine BMSM’s experiences with police, we also reviewed gray literature on racial and sexual minorities’ experiences with law enforcement (e.g., government reports, civil society reports, and newspaper articles [23, 24]) to identify additional potential pathways between policing practices and HIV risk. This resulted in a framework of three main pathways through which policing practices could influence HIV vulnerability (discrimination, mental health, and condom-carrying behaviors). We then searched for additional empirical research on the impact of policing across each of these pathways. Key words used for the review included the following: policing, law enforcement, sexual risk, HIV/AIDS, racism, stigma, discrimination, and sexual minorities. Using various combinations of these key words, we searched the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed online database, Web of Science, Psychinfo, JSTOR, and SocINDEX. The authors reviewed the titles, abstracts, and ultimately manuscripts for relevance and included articles only if they were written in English and focused either on the health-related outcomes of policing practices or on social determinants of HIV among sexual and/or racial minorities. We examined peer-reviewed articles from 1990 to 2017. This search produced a total of 424 citations, 293 of which were excluded based on review of the title, 60 of which were excluded based on review of the abstract, and 38 of which were excluded based on review of the full text. A total of 33 peer-reviewed articles were included in this study and informed the pathways used in this model, supplemented with 13 non-peer-reviewed studies.

Ethnographic Data Collection

Our model also draws on ethnographic data collected in NYC in 2014 as part of a community-based ethnographic study focused on the structural and community-level determinants of BMSM’s vulnerability to HIV [25]. Ethnographic data collection occurred in NYC between June 2013 and May 2014. We completed three 90-min in-depth interviews each with 31 BMSM. Interviews covered men’s past and current life experiences, across family, work, school, friends, sexual relationships, and men’s interactions with criminal justice. In addition, we conducted 60-min interviews with 17 community stakeholders including outreach workers, community advocates, and healthcare professionals who were involved in services and programs related to BMSM’s health. During this period, the study team also conducted participant observation at weekly community events, in public places frequented by BMSM (e.g., community-based organizations, gay bars, nightclubs, parks, streets, churches, and libraries) and in private spaces accompanied by five in-depth interviewees (e.g., private house parties, gay family dinners, police precincts, public cruising in parks). Participants were recruited through outreach and advertising in community clinics, bars, nightclubs in NYC, and also via the Internet. Eligibility criteria were being at least 15 years old, born as and identified as male, and having had anal or oral sex with a man in the past year.

Ethnographic Data Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and entered into Atlas.ti 7.0. The first and fourth authors analyzed the data using a codebook that included several code families. Codes were based on analytical themes that emerged from line-by-line coding of the interview data, the interview guide, and the existing research. The coders achieved an inter-coder agreement of greater than 80% and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the study team. This paper draws on several code families, including the following: “police and law enforcement,” “sexual behavior,” and “stigma and discrimination.”

Results

Sample Characteristics

The 31 BMSM in our sample had a mean age of 29 and were generally of lower socio-economic status (see Table 1). In the past year, 15 reported stable housing, 11 reported unstable housing, and 5 experienced homelessness. Eight reported full-time employment, 8 were employed part time, and 15 were unemployed. Ten had a history of incarceration, 21 reported ever being stopped by police, and 18 reported mistrust of police. Based on self-report, 23 were HIV negative, 5 were HIV positive, and 3 chose to not report HIV status.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Sample characteristics | Total N = 31 |

|---|---|

| Age | 29.0 (12.3)a |

| 15–24 | 17 |

| 25+ | 14 |

| Sexual identity | |

| Gay | 15 |

| Same gender loving | 3 |

| Bisexual | 4 |

| Discreet | 4 |

| Straight | 3 |

| Other (MSM, None) | 2 |

| HIV status (self-report) | |

| Negative | 23 |

| Positive | 5 |

| Undisclosed | 3 |

| Housing | |

| Stable | 15 |

| Precarious | 11 |

| Homeless | 5 |

| Employment | |

| Full time | 8 |

| Part time | 8 |

| Unemployed | 15 |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 5 |

| Public | 17 |

| Uninsured | 9 |

aMean (standard deviation)

Pathways to HIV Vulnerability

Policing, Racial Discrimination, and Mental Health

In our study, over two thirds (21/31) of the men we interviewed had ever been stopped and questioned by police while going about their daily lives. This is higher than a recent study of over 10,000 BMSM in 15 US cities, in which 31% reported an arrest in the last year [26], though the difference might be attributable to the distinct time frames (last year versus ever). Men in our study described being stopped at subway stations, shops, and in the streets near their homes and work places. Some younger men reported being questioned by police at their schools. Many reported arrests for minor infractions such as using the subway without a metro card, possession of marijuana, urinating in the street, or dropping litter. Erik (21, bisexual) was arrested for throwing a piece of paper on the floor of a train station. He was also stopped and searched on the way home from his job as a waiter, because “the cops told me that I resemble a homicide suspect” (21, bisexual). Men reported feeling “watched” when they were in public places. Bob (48, straight) recounted how he felt uncomfortable in Manhattan’s wealthier neighborhoods and explained: “It’s like they [the police] watch you, every move you make, and that makes you feel uncomfortable because it’s like, you know your motives.” Chance (21, gay), who spent the night in jail after he jumped a turnstile on his way to high school, recounted being “singled out” because of his race.

“I think, to me, it’s a racial thing... I see a white kid, he hopped the turnstile, they stopped him, showed a badge, whatever. Sat him down, got him in handcuffs just for security reasons, and they let him go and they give him a ticket… I hop the turnstile, you arrest me and go to jail, and you don’t send him to jail either? That’s racist.”

Similarly, Dylan (22, gay), who attended a prestigious university in NYC, described being frequently targeted on his way to and from campus:

“So the police came up and they started just questioning what we were doing, why we were there. And of the people who were there, I felt singled out because I was visibly a person of color and the majority of them were not.”

As depicted in Fig. 1 (arrows 1 and 2), racially discriminatory stop and frisk and misdemeanor arrests generate HIV vulnerability by affecting perceived racism. That is to say, unsurprisingly, Black men who experience high rates of stop, frisk, and arrest generally perceive they were targeted because of their race [27]; perceived racism is a well-known driver of sexual risk behaviors [21, 28]. A survey of over 2000 African American, White, and Latino adults found that 75% of Black men aged 18–34 report being victims of racial profiling [29]. One study found that Black men who have experienced discrimination-related trauma, (i.e., trauma that they attribute to their race or sexual orientation) engaged in elevated rates of unprotected anal intercourse compared to those who experienced non-discrimination-related trauma [21]. Perceived racial discrimination, which is one of the most commonly used indicators in research on racism and health [22], was associated with sexual risk behaviors in a sample of 526 Black heterosexual men [28], though it was not significantly associated with sexual risk behavior among 1369 MSM in NYC [30]. While we could not find any studies that specifically assessed the health or behavioral outcomes of police-related perceived racism, existing studies on the effect of racial discrimination on sexual risk [21, 28] suggest that police-related perceived racism could directly impact sexual risk behaviors (see Fig. 1 arrow 4).

As depicted in Fig. 1 (arrow 3), the experience of racially discriminatory policing practices may also produce HIV vulnerability by negatively impacting mental health. Around half of the 600,000 documented stop and frisks in NYC between 2004 and 2010 involved physical contact and 23% involved the use of force [31]. In the present study, several participants described being pushed and shoved onto the floor during police stops. One participant (17, gay) described being sprayed in the face with mace by a police officer on his way home.

“I was walkin’ home, and the cops they said I met somebody’s description… I was drunk. And when I get drunk, I’m very naïve. … he came up to me and I was like, ‘I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.’…And that’s when it went from there. I got maced. That was the worst feelin’ ever. It feel like your eyes is on fire or gettin’ scrambled or somethin’…”

This is consistent with qualitative studies that show that being arrested often involves being shoved around and being forced to sit or lie on the sidewalk [32]. A recent NYC-based study examined the relationship between involuntary police contact and mental health among a racially diverse sample of over 1000 young men and found that both frequency and intrusiveness of police contact were associated with increased self-reported trauma, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [17]. Research showing that involuntary police contact is often experienced as distress, hopelessness, and feelings of injustice [33] and that negative perceptions of policing are linked to higher reported levels of stress [18] underlines the mental health harm caused by racially discriminatory stop and frisk and misdemeanor arrests.

Despite the paucity of peer-reviewed research examining how exposure to racially discriminatory policing practices shape mental health and sexual risk behaviors [17], decades of public health research unequivocally show that perceived racism is associated with poor mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and trauma [22], all of which are known risk factors for sexual risk behaviors including inconsistent condom use and sero-discordant unprotected insertive anal intercourse [20].

Policing and Sexual Discrimination

As depicted in Fig. 1 (arrows 4, 5, 6, and 7), discrimination based on sexuality may also produce HIV vulnerability among BMSM. While few peer-reviewed studies examine police-related sexual discrimination [34], the targeted policing of sexual minorities in public spaces, which is often justified on the basis of suspicion of sex work, has been documented across the urban US [23, 35, 36]. Several reports, including one conducted by the US Department of Justice [23, 35], show that when sexual minorities are stopped and searched by police, they may experience discriminatory language, humiliation, and unnecessary strip-searches. In NYC, LGBTQ survey respondents reported higher levels of verbal and physical abuse by police officers than non-LGBTQ respondents [36]. Data also suggest that within the LGBTQ community, BMSM are particularly likely to experience police-related sexual discrimination. Between 2010 and 2015 in NYC, Black sexual minorities were more likely than any other racial group to file police-related complaints based on sexual orientation or gender presentation [24].

Sexual discrimination is a known source of HIV vulnerability [30, 37] (arrow 6) and has been linked directly to HIV risk behaviors among MSM [37]. An NYC-based study among MSM found that sexual orientation-based discrimination was associated with unprotected insertive anal intercourse with a partner of unknown or HIV-negative status [30]. This intersection of racial and sexual discrimination was demonstrated by a study of over 1000 Latino MSM in NYC and Los Angeles which found that MSM who were exposed to both homophobia and racism had higher odds of reporting unprotected receptive anal intercourse with a casual sex partner than men exposed to only homophobia or racism or to neither [38]. As depicted by arrow 7, sexual discrimination also shapes HIV vulnerability through its impact on mental health. Among BMSM, sexual discrimination has been associated with anxiety and depression, both of which are known HIV risk factors [39].

The paucity of research on sexual minority’s interactions with police extends to work on how gender presentation may shape police interactions with BMSM (arrow 8) and other sexual minorities. Reports that examine sexual minority’s interactions with police [35, 36] generally do not distinguish between sexuality and gender presentation in their analyses of discrimination. Among the men in our study, those with more feminine gender presentation described being stopped in public places on suspicion of sex work, which they attributed to their non-conforming gender presentation. As shown in Fig. 1 (arrows 8, 9, and 10), more research is needed to examine BMSM’s experiences of gender-presentation-based discrimination, and the potential consequences of this kind of discrimination for mental and sexual health.

Policing and the Use of Condoms as Evidence

In addition to stop and frisk and misdemeanor arrests, one policing practice—condoms as evidence—stood out as particularly important in shaping HIV vulnerability among BMSM. In many parts of the urban US, police may use possession of condoms as evidence of sex work in criminal prosecutions [40]. In recent years, condoms as evidence has been prohibited in several parts of the US including New York State, California, and Washington DC, however, it remains permissible many major US cities [40]. Reports across the urban US suggest that racial minorities have been disproportionately targeted by condoms as evidence [36, 40]. Our research in NYC suggests condoms as evidence continues to shape BMSM’s behavior, even though the law itself has been repealed. Interviews with BMSM revealed considerable confusion around the legal status of condoms: some continued to believe that condoms could serve as evidence of sex work, and others thought it was illegal to carry condoms in public places. One participant, who was currently making money through sex work, explained that he did not carry condoms when engaging in sex work in public places because he was worried he’d be racially profiled. Another participant (Darnell, 29, gay) explained:

“I was in this program… They told us that they stop people. First, people for having condoms on them, which is crazy. I feel that why would you lock someone up for that unless you caught them doing it [sex work]?... That’s just really stupid.”

Thus far, no peer-reviewed studies have assessed the effects of condoms as evidence on condom-carrying behaviors (arrow 11). However, qualitative reports suggest that condoms as evidence can discourage populations at disproportionate risk of HIV (including sex workers, transgender populations, and LGBT youth) from carrying condoms due to fear of arrest [40]. Not carrying condoms is a known risk factor for unprotected sex (arrow 12) [41], thus it is highly plausible that the cultural impact of condoms as evidence may have a lingering effect on sexual and racial disparities in HIV.

Discussion

This paper advances research on racism and health disparities by delineating multiple pathways through which policing practices may generate HIV vulnerability among BMSM (see Fig. 1). While a great deal has been written about the impact of racism on health [25], policing practices and racism are rarely discussed in combination in HIV research, perhaps because a lot of this work has been conducted outside the US, or, when conducted in the US, has focused on IDUs or sex workers [19]. Our conceptual model offers a way to examine policing as a modifiable source of community-level HIV vulnerability among a sexual minority population [42]. This model adds detail to existing models of racial health disparities which have examined how the War on Drugs [43] drive racial HIV disparities.

The findings presented in this paper underline the continued need for policies and interventions that address the structural drivers of HIV among BMSM. This study suggests that individual-level biomedical prevention approaches such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and behavior-change counseling, which continue to be emphasized in current HIV prevention efforts and research agenda [44], must be complemented by efforts to identify and transform specific modifiable elements of the structural environment in which BMSM live. Our work here points to the need for research, interventions, and policies to reform policing and to end the discriminatory practices which produce racial health disparities.

Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

Our conceptual model highlights that research into the public health consequences of policing practices is still in its infancy. Several of the model’s pathways are suggestive rather than conclusive, pointing to critical avenues for future research. First, studies are urgently needed to quantitatively assess the health and behavioral outcomes of exposure to policing practices, in particular stop and frisk, intrusive searches, misdemeanor arrests, and arrests without probable cause. Second, given that existing studies of police discrimination tends to examine only one aspect of discrimination at any one time, for example, racial [12] or sexual discrimination [35], we recommend that future research into the public health consequences of policing practices in the urban US should have, at the center of its analysis, a consideration of the multiplicative impacts of racial, sexual, and gender performance discrimination. Third, though the effects of racial and sexual discrimination on mental and sexual risk behaviors are well documented, further research is needed to assess the health consequences of discrimination based on gender presentation. Finally, given that several cities have changed laws about condoms as evidence, future comparative work across cities should assess the health impact of these legal changes. The effectiveness of community-level strategies hinges upon a better understanding of how social inequality produces vulnerability. These avenues for research will provide the empirical basis for the development of innovative community-level strategies, which in combination with biomedical HIV prevention, will be vital to address the disproportionately high HIV infection rates that BMSM continue to experience in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (1 R01 MH098723).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African American gay and bisexual men. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html. Published 2014. Accessed 18 Jan 2016

- 2.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, 4th, Wilson PA, Rourke SB, Heilig CM, Elford J, Fenton KA, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radcliffe J, Doty N, Hawkins LA, Gaskins CS, Beidas R, Rudy BJ. Stigma and sexual health risk in HIV-positive African American young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(8):493–499. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodreau SM, Rosenberg ES, Jenness SM, Luisi N, Stansfield SE, Millett GA, Sullivan PS. Sources of racial disparities in HIV prevalence in men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA, USA: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(7):e311–e320. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30067-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.New York City Office of the Mayor. Disparity report.; 2016. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/ymi/downloads/pdf/Disparity_Report.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2016

- 6.American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The war on marijuana in Black and White; 2013. https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/1114413-mj-report-rfs-rel1.pdf#11. Accessed 04 Sept 2016

- 7.Levine H, Siegel L. Criminal court summonses in New York City: summonses for violating NYC AC 19-176, Average Number 2008-2011. Presented at the public event: “Summons: The Next Stop and Frisk,” CUNY School of Law, Long Island City, NY; 2014. https://marijuana-arrests.com/docs/Criminal-Court-Summonses-in-NYC--CUNY-Law-School-April-24-2014.pdf. Accessed 03 Dec 2016

- 8.Mauer M. The changing racial dynamics of the war on drugs. Sentencing Project Washington, DC; 2009. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/media/publications/sentencing_project_report_on_changing_racial_dynamics_in_war_on_drugs_2009.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2017

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables; 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed 20 Sept 2017 [PubMed]

- 10.National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). NAACP criminal justice fact sheet. NAACP. http://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/. Published 2015. Accessed 20 Sept 2017.

- 11.Cooper HL, Fullilove M. Editorial: excessive police violence as a public health issue. J Urban Health. 2016;93(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0040-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabrielson R, Jones RG, Sagara E. Deadly force, in Black and White: a ProPublica analysis of killings by police shows outsize risk for young black males. ProPublica J Public Interest. 2014. Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/deadly-force-in-black-and-white. Accessed 10 Oct 2014.

- 13.Karch DL, Logan JE, McDaniel D, et al. Surveillance for violent deaths–National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 States, 2009. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. September 14, 2012 / 61 (ss06); 1–43, Atlanta GA.

- 14.United States (US) Department of Justice. Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department. Civil Rights Division; 2016. Penny Hill Press, Damascus, Maryland

- 15.Meares TL. The law and social science of stop and frisk. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. 2014;10(1):335–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sewell AA, Jefferson KA. Collateral damage: the health effects of invasive police encounters in New York City. J Urban Health. 2016:93(1):42–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez MB. Policing, community fragmentation, and public health: observations from Baltimore. J Urban Health. 2016:93(1):154–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Strathdee S, Hallett T, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):268–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Bright D, Cranston K, Isenberg D, Bland S, Barker TA, Mayer KH. Clinically significant depressive symptoms as a risk factor for HIV infection among black MSM in Massachusetts. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):798–810. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9571-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ, Schuster MA. Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):875–880. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, Carter RT. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: a meta-analytic review. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Department of Justice. Investigation of the New Orleans Police Department. Civil Rights Department; 2011. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2011/03/17/nopd_report.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2016

- 24.New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board. Pride, prejudice and policing: an evaluation of LGBTQ-related complaints from January 2010 through December 2015; 2016. http://www.nyc.gov/html/ccrb/downloads/pdf/LGBTQ-Report.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2016

- 25.Parker CM, Garcia J, Philbin MM, Wilson PA, Parker RG, Hirsch JS. Social risk, stigma and space: key concepts for understanding HIV vulnerability among black men who have sex with men in new York City. Cult Health Sex. 2016;0(0):1–15. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1216604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim JR, Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Spaulding AC, DiNenno EA. History of arrest and associated factors among men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2011;88(4):677–689. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weitzer R, Tuch SA. Racially biased policing: determinants of citizen perceptions. Soc Forces. 2005;83(3):1009–1030. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowleg L, Burkholder GJ, Massie JS, Wahome R, Teti M, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. Racial discrimination, social support, and sexual HIV risk among Black heterosexual men. AIDS Behav. 2012;17(1):407–418. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weitzer R, Tuch SA. Perceptions of racial profiling: race, class, and personal experience. Criminology. 2002;40(2):435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00962.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frye V, Nandi V, Egan J, Cerda M, Greene E, van Tieu H, Ompad DC, Hoover DR, Lucy D, Baez E, Koblin BA. Sexual orientation- and race-based discrimination and sexual HIV risk behavior among urban MSM. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):257–269. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0937-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagan J, Fagan J. Expert testimony. 2010. Floyd et al. v. City of New York, et al. 08 Civ. 1034, SAS.

- 32.Brunson RK. “Police don’t like black people”: African-American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminol Public Policy. 2007;6(1):71–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunson RK, Weitzer R. Police relations with black and white youths in different urban neighborhoods. Urban Aff Rev. 2009:44(6):858–885.

- 34.Finneran C, Stephenson R. Gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of police helpfulness in response to male-male intimate partner violence. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(4):354–362. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.3.15639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Williams Institute. Discrimination and harassment by law enforcement officers in the LGBT community; 2015. http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Discrimination-and-Harassment-in-Law-Enforcement-March-2015.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2016

- 36.Make the Road New York. Transgressive Policing police abuse of LGBTQ communities of color In Jackson Heights Report by Make the Road New York October 2012; 2012. http://www.maketheroad.org/pix_reports/MRNY_Transgressive_Policing_Full_Report_10.23.12B.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2016

- 37.Preston DB, D’Augelli AR, Kassab CD, Starks MT. The relationship of stigma to the sexual risk behavior of rural men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2007;19(3):218–230. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuno Y, Borkowf C, Millett GA, Bingham T, Ayala G, Stueve A. Homophobia and racism experienced by Latino men who have sex with men in the United States: correlates of exposure and associations with HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):724–735. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9967-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi K-H, Paul J, Ayala G, Boylan R, Gregorich SE. Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):868–874. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Human Rights Watch. Sex workers at risk: condoms as evidence of prostitution in four US cities; 2012. https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/07/19/sex-workers-risk/condoms-evidence-prostitution-four-us-cities. Accessed 26 Oct 2015

- 41.Hart T, Peterson JL. Predictors of risky sexual behavior among young African American men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1122–1124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsch JS. Labor migration, externalities and ethics: theorizing the meso-level determinants of HIV vulnerability. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerr J, Jackson T. Stigma, sexual risks, and the war on drugs: examining drug policy and HIV/AIDS inequities among African Americans using the Drug War HIV/AIDS Inequities Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;37:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP). National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020; 2015. https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2016