Abstract

Urban decay is the process by which a historical city center, or an old part of a city, falls into decrepitude and faces serious problems. Urban management, therefore, implements renewal mega projects with the goal of physical and functional revitalization, retrieval of socioeconomic capacities, and improving of quality of life of residents. Ignoring the complexities of these large-scale interventions in the old and historical urban fabrics may lead to undesirable consequences, including an additional decline of quality of life. Thus, the present paper aims to assess the impact of renewal mega projects on residents’ subjective quality of life, in the historical religious district of the holy city of Mashhad (Samen District). A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods of impact assessment, including questionnaires, semi-structured personal interviews, and direct observation, is used in this paper. The results yield that the Samen Renewal Project has significantly reduced the resident’s subjective quality of life, due to its undesirable impacts on physical, socio-cultural, and economic environments.

Keywords: Quality of life, Urban renewal, Mega project, Impact assessment, Mashhad, Iran

Introduction

Decaying the primary cores and historical districts of cities is one of the most common challenges in the urban development process. As these areas dilapidate physically, not only do they lose their ability to meet the needs of the residents but also they pose social, cultural, and economic challenges to the city [1]. In addition, the historical, sociocultural, and economic values incorporated in these areas necessitate the urban management intervening under urban renewal projects. These large-scale interventions aim for physical and functional revitalization, retrieval of socioeconomic capacities, and improvement of quality of life (QOL) of residents [2]. On the other hand, lack of comprehensive perspective in preparation and implementation of these mega projects may cause undesirable physical, sociocultural, and economic consequences, and significantly degrades the QOL in these traditional urban fabrics [3]. Indeed, not only is the improvement in QOL one of the first and foremost targets of urban renewal projects in worn-out districts but also implementation of these mega projects and their physical, socio-cultural, and economic impacts can change the QOL, directly and indirectly. Measuring the QOL during the implementation of urban renewal projects can help assess previous planning strategies and policies, identify residents’ dissatisfaction factors, prioritize problems and challenges, and design future planning policies to improve the strengths and reduce the weaknesses of the projects [4, 5].

In recent years, an examination of QOL in urban areas has been widely approached by researchers in various fields. In this regard, the QOL has been the focus of widespread urban planning studies as a tool for planning livable and sustainable cities [6, 7]. However, these studies vary in several aspects, such as QOL definitions, conceptual models, domains, geographical scale, indicator type, time frame, and context [8, 9]. QOL studies are different from one another, not only conceptually but also in terms of methodology and measurement indicators. While the “Quality of Life” has long been an explicit or implicit policy goal, a universally acceptable definition has not been arrived at yet [10]. This is due to the fact that the concept of QOL is a broad multidimensional and relative concept [11]. The central methodological debate is the distinction between the two concepts of subjective and objective QOL. The objective approach is most typically limited to the analysis, and reporting of secondary data usually aggregate data at different geographic or spatial scales. In contrast, the subjective approach is specifically designed to collect primary data at the disaggregate or individual level using social survey methods where the focus is on the peoples’ behaviors and assessments of different aspects of QOL in general and of quality of urban life in particular [12, 13]. In this regard, various domains and indicators have been used to measure the QOL due to differences in the goals and targets of the study, the personal judgment of the researcher, the characteristics of the study area, and the availability of data (Table 1). On the other hand, while measuring the QOL in urban districts has been widely approached in recent years, study on the relationship between a renewal intervention and QOL has rarely been taken into consideration, which is the main contribution of the present paper to the body of literature.

Table 1.

Representative definitions and domains of quality of life

| Quality of Life definitions | |

|---|---|

| Szalai [14] | Life quality refers to the degree of excellence or satisfactory character of life. |

| Marsella et al. [15] | The individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals. |

| Musschenga [16] | The good life is a combination of enjoyment (positive mental states), satisfaction (evaluation of success in realizing a life-plan or personal conception of the good life), and excellence (the virtuousness or value of a person’s activities). |

| Mulligan et al. [17] | The satisfaction that a person receives from surrounding human and physical conditions. |

| McCrea et al. [18] | A broad term which encompasses notions of a good life, a valued life, a satisfying life, and a happy life. |

| Das [11] | Well-being or ill-being of people and the environment in which they live. |

| Carr [19] | Life quality at a precise moment in time. |

| Quality of Life domains | |

| Cummins [20] | Material well-being, health, productivity, belonging, safety, community, and emotional well-being. |

| Mitchell [21] | Security, health, personal development, community development, physical environment and natural resources, and goods and services. |

| Hazel et al. [22] | Education, employment, energy, environment, health, human rights, income, infrastructures, security, reform, and housing. |

| Mitchell et al. [23] | Health, physical environment, natural resources, personal development, and security. |

| Johansson [24] | Economic resources and status of consumers, status of employment and work, accessibility to educational opportunities, health and medical care, family and social relationships, housing and its facilities, culture and leisure, personal security and properties, political resources and participation. |

| Kamp et al. [8] | Person characteristics, health, economy, services accessibility, built environment, natural resources, natural environment, safety and security, community, culture, and life style. |

| Rojas [25] | Health, economy, career, family, friends, one’s self and community. |

| Lee [4] | Civic services, neighborhood satisfaction, community status, neighborhood environmental assessment, and local attachments. |

Methods

Data Collection and Study Variables

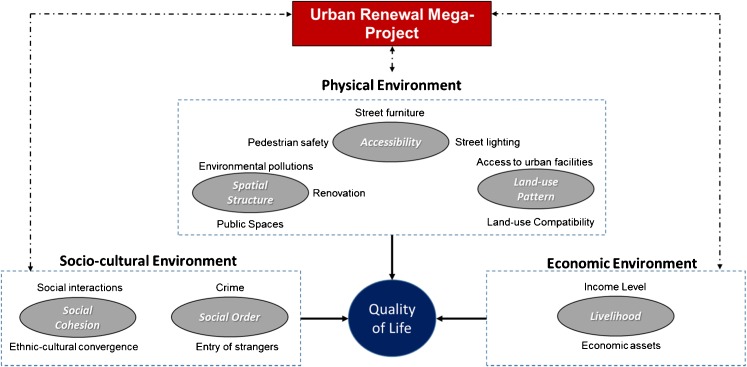

The main purpose of the present paper is assessing the impact of urban renewal mega projects on local communities’ subjective quality of life, with a focus on historical religious center of Mashhad Metropolis. Since urban mega projects can cause a combination of quantitative and qualitative impacts, we need to combine the quantitative and qualitative assessment methods to deeply understand these effects. The present study used mixed-methods sequential explanatory design, which implies collecting and analyzing quantitative and then qualitative data in two consecutive phases within one study. This method typically is used to explain and interpret the quantitative results through a qualitative analysis [26, 27]. This paper used questionnaires, semi-structured personal interviews, and direct observation as data-collecting techniques. The sampling method was systematic random sampling with random walk technique. In this technique, instructions are given to the interviewer to follow a random route and interview individuals (take first road right, interview at second house on your left, continue down the road, interview tenth household on your right, and so on) [28]. The paper used IBM SPSS Sample Power (version 3.0.1) to determine the sample size for the questionnaire. Considering the maximum probability of 5% for error type I and 20% for error type II (minimum test power of 80%) and the minimum effect size of 0.2, the required sample size was calculated as 150. For personal interviews, the sample size was based on theoretical saturation. Thirty local residents, 15 local shopkeepers, 10 pilgrims, and 3 real estate consultants were studied in depth through semi-structured interviews. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model of QOL of this research considering the main targets of the study, the characteristics of the study area, and the availability of data.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of components and domains that contribute to subjective quality of life

Case Study

Mashhad is the second most populous city in Iran and the second-largest holy city in the world [29]. Mashhad attracts more than 30 million tourists and pilgrims every year, many of whom come to pay homage to the Imam Reza shrine (the eighth Shi’ite Imam). It has been a magnet for travelers since the medieval times. The central district of Mashhad (the primary and historical core of the city around the Holy Shrine which is known as Samen District) was facing serious physical and functional deterioration. With the goal of improving quality of life of residents and upgrading the performance and competitiveness of the tourism industry, a large-scale governmental intervention was planned under the “Samen Renewal Project” in 1992. The project is the largest and longest-running public-sector renewal intervention in Iran. Nowadays, this urban renewal mega project, which runs in an area of approximately 366 ha by Samen Renovation Organization, has become a major challenge to the Mashhad’s urban management. So, this project has only achieved 50% physical progress about 25 years after it started [30].

Such a large-scale and long-term intervention in the historical religious fabric of the city has led to a wide range of impacts and consequences, one of the most important of which is changing the QOL. In this regard, zone 3 of Samen District has experienced the highest degree of physical intervention among the rest of the district. With over 104 ha, this sector accounted for about 30% of the total Samen District, and with a population of 5365 ranking second among the rest of the district. At present, the zone is a perfect laboratory to assess the impacts of large-scale renewal project on quality of life in historical urban districts (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Samen District of Mashhad and the study area

Results

In the statistical sample, 76 males (50.7%) and 74 females (49.3%) responded to the questionnaire which indicates a common sexual ratio (102.7). The average age is 36.9, the lower bound is 17, and the upper bound is 72. 46% of the sample population are non-native, indicating the high degree of immigration within the study area. In addition, 36.7% of the respondents were living in the area for less than 5 years and 65.3% less than 10 years, which represents the evacuation of the study area by permanent local residents. Table 2 represents the results of the questionnaire in which the local residents’ satisfaction with physical, socio-cultural, and economic circumstances of their living environment was inquired.

Table 2.

Local residents’ satisfaction from their living environment.

| Components | Domains | Indicators | Completely dissatisfied (%) | Dissatisfied (%) | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (%) | Satisfied (%) | Completely satisfied (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical environment | Accessibility | Street lighting | 38.0 | 30.7 | 27.3 | 3.3 | 0.7 |

| Street furniture | 34.0 | 37.3 | 23.3 | 4.7 | 0.7 | ||

| Pedestrian safety | 28.7 | 39.3 | 27.3 | 4.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Spatial structure | Renovation | 30.0 | 42.7 | 20.7 | 6.7 | 0.0 | |

| Public spaces | 40.0 | 35.3 | 19.3 | 4.0 | 1.3 | ||

| Environmental pollutions | 28.7 | 43.3 | 24.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Land-use pattern | Access to urban facilities | 29.3 | 40.0 | 26.0 | 4.0 | 0.7 | |

| Land-use Compatibility | 22.7 | 51.3 | 22.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Socio-cultural environment | Social order | Crime | 38.0 | 41.3 | 16.7 | 4.0 | 0.0 |

| Entry of strangers | 32.7 | 41.3 | 21.3 | 4.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Social cohesion | Social interactions | 16.7 | 36.0 | 36.7 | 8.7 | 2.0 | |

| Ethnic-cultural convergence | 36.7 | 36.7 | 20.0 | 6.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Economic environment | Personal livelihood | Income level | 47.3 | 34.7 | 14.7 | 3.3 | 0.0 |

| Economic assets | 46.0 | 35.3 | 15.3 | 3.3 | 0.0 |

Table 3 shows that, on average, the sample population scored their own QOL of 3.30 on a scale ranging from 1 to 10. In fact, the respondents assessed their own QOL (subjective QOL) to be lower than the average level (5.50). On the other hand, the comparison of subjective QOL by sex shows that the women’s average score was lower than the men’s QOL average score. In addition, one-sample t test indicates that the sample results can be generalized to the statistical population and the subjective QOL in the statistical population is also lower than the average level with a confidence level of 99% (Table 4). Pearson correlation coefficient shows that physical circumstances of the environment have the strongest correlation with the subjective QOL among the components in the study area. In fact, by increasing the satisfaction of the physical environment, the residents’ subjective QOL increases, and vice versa. In addition, the domain of social order has the strongest correlation with the subjective QOL (Table 5).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for quality of life in the study area

| Statistic | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | 95% confidence interval for mean | Median | Mode | Variance | Std. deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Range | |||

| Mean | Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Total | 3.3000 | 2.9868 | 3.6132 | 3.0000 | 2.00 | 3.768 | 1.94125 | 1.00 | 9.00 | 8.00 | |

| Men | 4.1579 | 3.7490 | 4.5668 | 4.0000 | 3.00 | 3.201 | 1.78925 | 2.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | |

| Women | 2.4189 | 2.0278 | 2.8100 | 2.0000 | 1.00 | 2.850 | 1.68805 | 1.00 | 8.00 | 7.00 | |

| N | Skewness | Std. error of skewness | Kurtosis | Std. error of kurtosis | |||||||

| 150 | 0.790 | 0.198 | − 0.200 | 0.394 | |||||||

Table 4.

One-sample t test for quality of life in the study area

| One-sample t test test value = 5.5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean difference | 95% confidence interval of the difference | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| − 13.880 | 149 | 0.000 | − 2.20000 | − 2.5132 | − 1.8868 |

Table 5.

Correlation between components/domains with quality of life in the study area

| Components/domains | Quality of life | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson correlation | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

| Physical environment | 0.878** | 0.000 |

| Accessibility | 0.819** | 0.000 |

| Spatial structure | 0.842** | 0.000 |

| Land-use pattern | 0.780** | 0.000 |

| Socio-cultural environment | 0.874** | 0.000 |

| Social order | 0.869** | 0.000 |

| Social cohesion | 0.748** | 0.000 |

| Economic environment | 0.747** | 0.000 |

| Livelihood | 0.747** | 0.000 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Accessibility

One of the factors affecting the QOL in the urban neighborhoods is residents’ access to business centers, employment cores, and recreation centers. In this regard, pedestrians’ access to safe paths with adequate facilities (especially for vulnerable groups such as children, women, elderly, and disabled people) plays a key role [27]. Suitable street lighting, proper urban furniture, and the safety of pedestrians are essential requirements of an appropriate access [31]. Nearly 70% of the respondents were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the lighting of the passageways. Concerning the efficiency of urban furniture, 34% of the respondents were completely dissatisfied, 37.3% were dissatisfied, 23.3% were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4.7% were satisfied, and only 0.7% were completely satisfied. Additionally, more than two thirds of the respondents were completely dissatisfied or dissatisfied with the safety of the pedestrians.

One of the main goals of Samen Renewal Project was to reorganize the existing roads and local streets, as well as construction of new link routes to improve the access of residents and pilgrims to commercial, recreational, and accommodation centers, and also, the Holy Shrine. In this regard, the construction of two boulevards and a few service routes around the renovated commercial-residential centers are the main actions of the project in the study area [30]. Construction of these new roads has led to extensive destruction of the old routes in this zone. As a result, the residents and pilgrims have been forced to use alternative and temporary routes over two decades.

Field survey indicates that only the service routes that belong to the renovated commercial-residential parts (shopping malls, luxury hotels, and accommodation centers) are well designed and well equipped with the proper lighting and furniture. In contrast, the temporary routes (which include most of the pathways in the study area) lack appropriate street lighting and well-designed urban furniture.

In addition, the temporary routes lack necessary safety precautions for pedestrians against cars and motorcycles. Indeed, the Samen Renovation Organization has prioritized providing access to income-generating commercial-residential projects and has ignored the improvement of temporary local routes that are considered costly. This has severely reduced the accessibility quality in the study area.

...The renewal project has had nothing but destruction for the residents of this neighbourhood. Many local streets have been destroyed in order to access to commercial centers, hotels and hostels. Instead, the authorities have opened temporary pathways which cannot be used at night even with a flashlight... (man, 38 years old, local resident).

Spatial Structure

Spatial structure of an urban fabric reflects the coordination between built environment with underlying socio-economic circumstances [32]. Renewal Projects can facilitate urban life and improve the quality of the environment by constant renovation, increasing of well-equipped public spaces, and reduction of environmental pollutions. In this regard, more than 70% of the respondents were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the constant renovation, the desirability of public spaces, and also, the environmental pollutions in their living area.

One of the most comprehensive indicators for understanding the renovation status in an urban district is the issued construction permit index. Table 6 indicates that the number of building construction permits in the Samen District was a very small proportion of the entire city during 2013–2015. So, the construction permits issued in Samen District in 2013 were 60 (0.8% of the entire city), in 2014, it was 19 (0.03% of the entire city), and in 2015, it was 19 (0.5% of the entire city). On the other hand, although the number of issued permits is negligible, they cover a large area; average area of each of the permits in 2013 is 8640 m2, in 2014, it is 4156 square meters, and in 2015, it is equal to 6039 m2. Simply put, the construction permits issued in Samen District have been for large-scale residential and commercial projects, not for the local residents’ properties. This clearly reflects the capitalistic approach that sponsors this renewal project. An approach emphasizes commercialization and commodification of residential neighborhoods to finance for mega projects, rather than improving residents’ quality of life.

Table 6.

Issued construction permits in Samen District [29]

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Area (m2) | Number | Area (m2) | Number | Area (m2) | |

| Samen District | 60 | 518,425 | 19 | 78,980 | 19 | 114,756 |

| City of Mashhad | 7126 | 10,433,601 | 52,694 | 6,107,748 | 3492 | 4,091,856 |

| % of the total | 0.8% | 4.9% | 0.03% | 1.29% | 0.5% | 2.8% |

On the other hand, interviews with real estate consultants reveal that implementation of Samen Renewal Project is an important factor in decline of small-scale renovation by the residents. As soon as the project was launched, the Samen Renewal Organization issued a freezing decree to suspend the construction permits and to prohibit local people from selling their properties other than the organization. As a result, private constructions and small-scale renovations stopped at once. In this situation, local residents are faced with deterioration of their properties and neighborhood. They should either sell their properties at a low price to the organization or wait for an uncertain future [33]. In addition, the field survey shows that new spaces resulting from the destruction of old buildings, which could have been used as urban open spaces, either are currently used as parking lots or become indefensible spaces that significantly exacerbated security problems in the study area.

... Before the project started, our neighbourhood had places where the youth or the elderly could get together and spend their free time. But after the destruction, no place is left for us to hang out. This project has only created many ruins which are the suitable places for delinquency and crime... (woman, 59 years old, local resident).

Moreover, although one of the main justifications for the Samen Renewal Project was unsanitariness of the Samen District [30], the interviews and field surveys demonstrate that environmental pollution is significantly exacerbated. In this regard, the demolished buildings and ruins have become rubbish and construction waste dumps. In this respect, Mashhad Health Organization ranks the Samen District first in outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Mashhad [33]. On the other hand, long-term construction of commercial-residential centers and roads has led to noise pollutions. These pollutions can affect the physical and mental health of the residents and, eventually, increase the incidences of infectious, microbial, respiratory, and cardiac diseases.

... We wish to return to the unsanitary situation before the project. The project has had nothing for us but dust, mud, noise, and ruins... (woman, 37 years old, local resident).

Land-Use Pattern

Land-use planning affects residents’ quality of life in two aspects: (1) change in residents’ access to urban facilities and (2) the environmental impacts of land uses in surrounding neighborhoods [3]. In this regard, nearly two thirds of the respondents were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with their access to urban facilities, and nearly three quarters were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the compatibility of activities within their living area.

It was expected that the Samen Renewal Project would carefully allocate the public facilities and services in order to balance the needs of residents against the pilgrims. However, the results are observed to be completely in contrast with these expectations. In 2008, due to slow progress of the project, the authorities decided to attract investors for financing and improving the speed of the implementation. To this end, the Samen Renewal Organization made important changes in the proposed land-use plan. Based on these changes, the proposed small-scale residential land uses were converted into large-scale commercial-residential activities. Consequently, many local houses were purchased using the legal power with low price from locals. These local properties were then aggregated and converted to large lots for the construction of commercial towers, malls and shopping centers, and luxury hotels. In fact, the Samen Renewal Organization concentrated on implementation of large-scale commercial and residential centers instead of providing educational, sanitarian, medical service centers. On the other hand, interviews with pilgrims revealed that these large-scale commercial and residential centers are only suitable for wealthy pilgrims and they have made it harder for the low-income pilgrims to access affordable services and facilities.

... In the past, we used to stay in local residents’ houses. They did not have good quality, but were very affordable for low-income pilgrims. Now these houses have been destroyed and luxury hotels have been built that most pilgrims cannot afford to stay in ... (man, 39 years old, pilgrim).

Social Order

Social order is contrasted to social chaos or disorder and refers to a stable state of society in which the existing social order is accepted and maintained by its members [34]. Failure to timely consider the factors exacerbating the social disorder can lead to serious problems in people’s everyday life. Scholars have corroborated that life quality is deeply affected by feelings of anomie and that anomic people tend to have a lower life satisfaction [35]. Crimes such as drug and alcohol trafficking, extortion, harassment, and prostitution can significantly reduce the QOL in urban neighborhoods. On the other hand, the strangers’ entrance to residential neighborhoods without adequate supervision not only can increase criminal activities but also has a significant reducing effect on life satisfaction [36]. In this regard, 79.3% of the respondents were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the number of criminal incidences in their area, and also, 74% were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the entrance of strangers in their personal living.

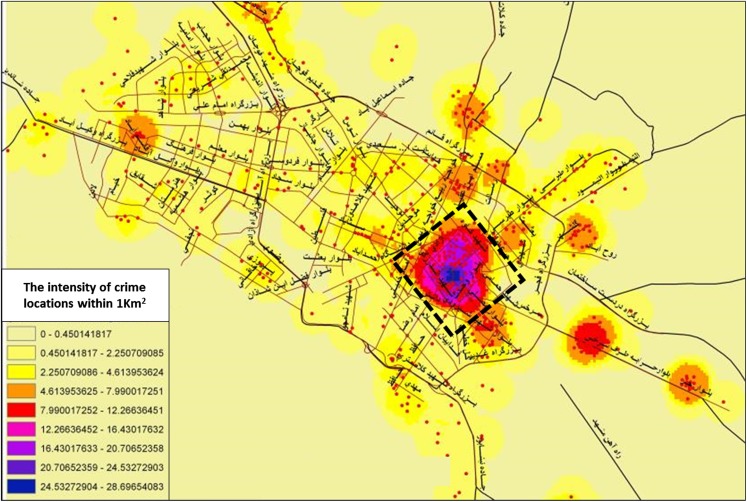

The 2016 official crime statistics of the Mashhad Police Department are consistent with the views of the respondents [37]. Integrating the crime statistics with the location of crime in Mashhad clearly indicates the concentration of crime hotspots in the Samen District (Fig. 3). In fact, the boundary of crime occurrence is clearly aligned with the physical boundary of Samen District. It represents a relation between the physical, socio-cultural, and economic circumstances of the district with the occurrence of crimes. In addition, examination of the number of defendants held in Mashhad Central Prison shows that the Samen District ranks first in crimes against public decency and morality, fraud, crime against person, and crime against property. Moreover, the district ranks second in other crimes, such as addiction, theft, and drug trafficking in the city of Mashhad (Fig. 4). In addition to undesirable socioeconomic circumstances of the district, lack of planning for indefensible spaces (corners and L- and U-shape spaces) and desolate properties that resulted from the widespread destructions of Samen Renewal Project has significantly contributed to the probability of crime.

...Robbery and extortion happen in this neighbourhood every day. The reason is clear: the entire neighbourhood is dark and ruined and turned into a crime place for thieves and addicts... (man, 53 years old, local shopkeeper).

Fig. 3.

Intensity of Crime Locations in Mashhad.

Fig. 4.

Number of defendants in each district of Mashhad

Interviews also show that the most important factor in increasing the strangers’ entrance is the unbridled increase in the number of residential units, hotels, and hostels constructed based on the recommendations of the renewal project. On the other hand, due to the degradation of the neighborhood quality, old residents have started to leave their houses to rent them to tourists and pilgrims illegally. Official statistics show that in the Samen District, there are currently 3300 illegal private houses used for pilgrims’ accommodation [33].

... Most of the old residents of the neighbourhood are gone now. Instead, many of their houses have turned into hostels. Sometimes seven families from seven different cities of Iran with seven different cultures stay in these hostels in a week... (woman, 45 years old, local resident).

Social Cohesion

Another factor influencing the quality of life is social cohesion. The social cohesion refers to the sense of integrity and convergence in a society and the level of social relations and group interactions based on shared and collective values [38]. More than half of the respondents were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the quality of social interactions, and nearly three quarters of them were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the ethnic-cultural convergence of their neighborhood.

In this regard, Fig. 5 obviously indicates that the Samen District has been experiencing significant population loss over the past two decades. The district is currently considered as a shrinking district, which is being evacuated from its residents. Two types of migration can be identified in the district. The first type is forced migration of old residents as a result of implementation of the project. In this regard, the Samen Renewal Organization has forced the local residents to sell their properties using its coercive leverage to provide enough land for the project. The second type concerns the residents who were resisting or refusing to sell their property at the beginning either because of the low price offered by the organization or for personal reasons such as attachment to their old residence. These residents were eventually forced to leave their neighborhoods due to the unfavorable environmental conditions that affect the quality of their lives. The interviewees believe that social interactions were significant before the project, and even relatives were living in the same neighborhood and in the vicinity. However, with the displacement of the old residents, the traditional social relations in these neighborhoods have declined severely. On the other hand, due to the low quality of the district, the new inhabitants are often from the poor migratory class. The Samen District is currently the second destination of non-Iranian immigrants in Mashhad, especially the Afghan-born [29]. As a result, ethnic-cultural harmony of the district has declined significantly.

Fig. 5.

Population change in Mashhad [29]

Livelihood

The personal/family livelihood not only has a direct impact on the subjective quality of life but also is an important factor in the ability of residents to participate in the renovation [39, 40]. The income level is directly related to resident’s employment, and the land and property are the most important economic assets in the Samen District. More than 80% of respondents are dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with the level of their income and economic assets.

The Holy Shrine has made the Samen District, one of the most profitable tourist attractions in Iran. The interviews show that, before the project, the main occupation of residents is tourist-related retailing as well as renting their personal houses to the pilgrims and tourists. However, the local retail trade has been heavily affected by the large-scale shopping centers and malls that are proposed by the project.

...After the project, many properties were destroyed and replaced by glamorous malls and shopping centres. Most of our customers were drawn to these centres. We did not have the ability to compete, so we lost our customers and had no choice but to close the shop... (man, 31 years old, local shopkeeper).

Interviews with real estate consultants reveal that the project has reduced the property value of local residents. The freezing decree prohibited local people from selling their properties other than the Samen Renewal Organization. However, the price set by the organization had a dramatic difference to the real value of the properties in a regular housing market. In fact, the organization bought the residents’ properties at a very low price by using eminent domain law in a coercive manner. On the other hand, long-term implementation of the project has had a diminishing impact on the value of local properties. Pointing to the fact that in the past, the neighborhood used to be a source of income for the residents, locals believe that the project has significantly removed their jobs and personal/family income.

…I definitely disagree with the positive impact of the project on the value of local properties. We had to sell off our properties for a cheap price; otherwise the Samen Renewal Organization would cut off our electricity, gas and drinking water services. The value increase has only happened to large-scale commercial lands owned by investors, not to the local properties… (women, 43 years old, local resident).

Discussion

Urban decay has no single cause in Iran; it results from a combination of interrelated factors including poor urban planning, lack of attention to infill development policies, lack of public-private investment to improve worn-out infrastructures and facilities, poverty of the local populace, and depopulation by old residents. Consequently, many inner city districts in Iran are blighted by unemployment, riddled with poor housing and socially excluded from more prosperous districts. In this condition, government renewal interventions seem to be necessary in the old urban fabrics. Such renewal projects often improve the physical and functional efficiency, restore socio-economic capacities, and improve the quality of life of residents. However, any intervention in local communities, against the potential benefits, can have significant social, cultural, economic, and environmental costs.

In this regard, the Samen Renewal Organization has physically intervened in the historical religious center of Mashhad with the goal of improving the residents’ quality of life and upgrading the performance and competitiveness of the tourism industry. Since its inception, a lack of access to sustainable and stable financial resources turned into a serious challenge for the implementation of this urban renewal mega project. As the federal and national government refused to allocate funds to the project, the renewal organization was forced to fund the project in a self-sufficient manner.

This financing pattern has made the initial goals of the project move towards the goals of investors. Subsequently, the development of tourism industry has become the main goal of the project as the best opportunity to attract investors in the historical religious center of Mashhad. In this regard, the organization has adopted a destructive, elitist, imposing, and non-cooperative approach to provide the investors’ interests relying on its political and financial power. This capitalist look to the residential neighborhoods around the Holy Shrine not only has marginalized social goals and the needs of the local populace but also has diminished the residents’ subjective quality of life due to its undesirable physical, socio-cultural, and economic consequences (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Samen renewal mega project and quality of life of residents

Conclusions

Decaying historical city centers and old urban districts cause serious challenges to the cities such as depopulation, economic collapse, abandoned buildings and infrastructures, high local unemployment, fragmented families, crime, and a desolate cityscape. Urban renewal projects are, therefore, planned by urban management in order to improve the decayed urban fabrics. However, the present paper demonstrates that a lack of comprehensive approach addressing all physical, socio-cultural, and economic issues of these large-scale interventions may lead to undesirable effects and significantly reduce the subjective quality of life of residents.

In this regard, the analyses show that the Samen Renewal Project has physically intervened in the historical religious center of Mashhad by adopting a destructive, top-down, capitalist, and non-cooperative approach relying on political and financial power. This intervention has had undesirable physical, socio-cultural, and economic impacts on residential neighborhoods surrounding the Holy Shrine of Mashhad Metropolis. On average, 69.3% of the respondents in the zone 3 of Samen District were dissatisfied or completely dissatisfied with accessibility, 73.3% with spatial structure, 71.6% with land-use pattern, 76.6% with social order, 63% with social cohesion, and 81.6% with livelihood in their living area. These undesirable effects have significantly reduced the residents’ subjective quality of life. The sample population scored their own QOL of 3.30 on a scale ranging from 1 to 10. In this respect, women’s subjective QOL is lower than men’s score. In addition, one-sample t test indicates that the subjective QOL in the statistical population is also lower than the average level with a confidence level of 99%. Furthermore, correlation analysis also revealed that the physical circumstances of the environment have the strongest correlation with the subjective QOL in the study area with Pearson coefficient of 0.878.

The present paper concludes that the Samen Renewal Project had a serious deviation from the initial goals of renovation towards the goals of investors. It happened due to lack of strategic planning for sustainable financing of the project by the Samen Renewal Organization. As a result, the capitalist vision for the residential neighborhoods around the Holy Shrine ignored the needs of locals against the interest of tourists, pilgrims, and especially investors. It should be emphasized that what can be seen now in the Samen District is not just a computational mistake in the formulation and implementation of the project. It is precisely happening because of political economy of Mashhad. Indeed, tourism industry attraction and its subsequent economic rent in the historical religious district of Mashhad have marginalized social goals, and consequently, the economic profitability has become a priority for the urban management. Thus, the future studies need to recognize the political economy of space in the historical religious district of Mashhad metropolis, and respond how the Samen Renewal Project can be revised based on residents’ quality of life, the needs of tourists, and the interests of investors.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that no body provided intellectual assistance, technical help, or special equipment or materials.

Funding Information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Amir Forouhar, Phone: +989359519993, Email: a.forouhar@aui.ac.ir.

Mahnoosh Hasankhani, Email: mahnoush.hasankhani@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dale OJ. Urban Planning in Singapore: The Transformation of a City. Oxford: Oxford university press; 1999.

- 2.Hoffman V. The lost history of urban renewal. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Place-making and Urban Sustainability. 2008;1(3):281–301. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forouhar A, Kheyroddin R. The impact of commercialization on the spatial quality of residential neighbourhoods: evidence from Nasr neighbourhood of Tehran. Geographical Planning of Space Quarterly Journal. 2016;6(20):63–84. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YJ. Subjective quality of life measurement in Taipei. Build Environ. 2008;43(7):1205–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.11.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesfazghi ES, Martinez JA, Verplanke JJ. Variability of quality of life at small scales: Addis Ababa Kirkos Sub-City. Soc Indic Res. 2010;98(1):73–88. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9518-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogerson RJ. Quality of life and city competitiveness. Urban Stud. 1999;36(5):969–985. doi: 10.1080/0042098993303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seik FT. Quality of life in cities. Cities. 2001;18(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/S0264-2751(00)00048-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamp Iv, Leidelmeijer K, Marsman G, Hollander A. Urban environmental quality and human well-being towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts: a literature study. Landsc Urban Plan. 2003;65(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00232-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Türksever AN, Atalik G. Possibilities and limitations for the measurement of the quality of life in urban areas. Soc Indic Res. 2001;53(2):163–187. doi: 10.1023/A:1026512732318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanza R, Fisher B, Ali S, et al. Quality of life: an approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecol Econ. 2007;61(2):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das D. Urban quality of life: a case study of Guwahati. Soc Indic Res. 2008;88(2):297–310. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9191-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soleimani M, Tavallaei S, Mansuorian H, Barati Z. The assessment of quality of life in transitional neighborhoods. Soc Indic Res. 2013;119(3):1589–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0563-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marans RW, Stimson RJ. Social Indicators Research Series: Investigating Quality of Urban Life: Theory, Methods, and Empirical Research. Vol 45: Springer Netherlands; 2011.

- 14.Szalai A, Andrews F. The quality of life: comparative studies, vol. 20. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980.

- 15.Marsella AJ, Levi L, Ekblad S. The importance of including quality-of-life indices in international social and economic development activities. Appl Prev Psychol. 1997;6(2):55–67. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80011-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musschenga AW. The relation between concepts of quality of life, health and happiness. J Med Philos. 1997;22(1):11–28. doi: 10.1093/jmp/22.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulligan G, Carruthers J, Cahill M. Urban quality of life and public policy: a survey. In: Capello R, Nijkamp P, editors. Contributions to economic analysis. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrea STK, Stimson R. What is the strength of the link between objective and subjective indicators of urban quality of life? Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2006;1(1):79–96. doi: 10.1007/s11482-006-9002-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr D. Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA; 2009.

- 20.Cummins RA. The domains of life satisfaction: an attempt to order chaos. Soc Indic Res. 1996;38(1):303–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00292050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell G. Indicators as tools to guide progress on the sustainable development pathway. London: Urban International Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazel H, Lickerman J, Flynn P. Calvert–Henderson quality of life indicators: a new tool for assessing national trends. Bethseda, MD: Calvert Group; 2000.

- 23.Mitchell G, Namdeo A, Kay D. A new disease-burden method for estimating the impact of outdoor air quality on human health. Sci Total Environ. 2000;246(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansson S. Conceptualizing and measuring quality of life for national policy. Social Indicators Research Series: Assessing Quality of Life and Living Conditions to Guide National Policy. Vol 11. Dordrecht: Springer; 2002.

- 25.Rojas M. Experienced poverty and income poverty in Mexico: a subjective well-being approach. World Dev. 2008;36(6):1078–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013.

- 27.Forouhar A. Estimating the impact of metro rail stations on residential property values: evidence from Tehran. Journal of Public Transport: Planning and Operations. 2016;8(3):427–451. doi: 10.1007/s12469-016-0144-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche CJ. Impact Assessment for Development Agencies: Learning to Value Change: Oxford: Oxfam; 1999.

- 29.Statistical Year Book of Mashhad. Mashhad: Department of Planning and Development of Mashhad Municipality; 2016. SYBM.

- 30.Report on the Samen Renewal Project. Mashhad: Department of Urban Planning and Architecture of Mashhad Municipality; 2002.

- 31.Sirgy J, Cornwell T. How neighborhood features affect quality of life. Soc Indic Res. 2002;59(1):79–114. doi: 10.1023/A:1016021108513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillier B, Greene M, Desyllas J. Self-generated neighbourhoods: the role of urban form in the consolidation of informal settlements. Urban Design International. 2000;5(2):61–96. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Report on the Residents’ Problems of the Central Fabric of Mashhad. Mashhad: City Council of Mashhad; 2016. RPCFM.

- 34.Hechter M, Horne C. Theories of social order : a reader. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 2009.

- 35.Western JS, Lanyon A. Anomie in the Asia Pacific region: the Australian study. In: Atteslander P, Gransow B, Western J, editors. Comparative anomie research: hidden barriers-hidden potential for social development. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd; 1999.

- 36.Huppert FA, Marks N, Clark A, et al. Measuring well-being across Europe: description of the ESS well-being module and preliminary findings. Soc Indic Res. 2009;91(3):301–315. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9346-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.the Official Crime Statistics of Mashhad City. Mashhad: Mashhad Police Department; 2016. OCSMC.

- 38.Perspectives on Global Development . Social cohesion in a shifting world. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2012. p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashley C, Carney D. Sustainable livelihoods; lessons from early experiences. London: Department for International Development; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karl M. Monitoring and Evaluating Stakeholder Participation in Agriculture and Rural Development Projects: A Literature Review. Rome: Sustainable Development Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United nations; 2000.