Abstract

The increase in the number of people who choose to have medical procedures done to improve their appearance may be due to changed social and cultural factors in modern society, as well to the ease of access and affordable costs of these cosmetic treatments.

Today, two elements legitimate recourse to this type of treatment: the broad definition of health accepted by the law and the scientific community, and the provision of meticulous information to the entitled party previous to obtaining his or her consent. In Italy, while current case-law views treatments exclusively for cosmetic purposes as unnecessary, if not even superfluous, it nonetheless demands that providers inform clients about the actual improvement that can be expected, as well as the risks of worsening their current esthetic conditions.

Keywords: Information, Cosmetic surgery, Cosmetic treatments, Liability

1. Introduction

The constant attention that jurisprudence gives to informed consent, such that the lack of this consent is an autonomous source of medical liability because of the unlawfulness of the healthcare treatments provided, takes on greater importance in the sphere of cosmetic treatments, above all in reference to the content and extensiveness of the obligation to provide information, in order to ensure that the patient’s decision to undergo the treatment proposed is truly aware and informed.

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in recourse to cosmetic treatments [1], also in dentistry [2].

In fact, according to data provided by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS), in 2005, the number of plastic surgeries increased by 440% in the U.S. In Great Britain, there was an increase of 23% from 2005 to 2007. The phenomenon is widespread in Asian countries as well, although unfortunately this service is often provided at “cosmetic surgery tourism” destinations, where cosmetic surgery treatments are provided at modest prices, but the standards of quality of the healthcare professionals and the structures are not always the highest [3].

Among the most important motivations for this tangible increase in requests for cosmetic treatments are social and cultural factors of modern consumer society, in which “appearing” is much more important than “being,” a philosophy of life amplified by the pervasive diffusion of advertising for cosmetic treatments and by media coverage that exaggerates results and minimizes risks [4].

A survey indicated that 71% of women and 40% of men deem a beautiful body and pleasant appearance to be priority requisites for success in work and social relations. It reported a marked increase in the recourse to cosmetic treatments by men and minors [5].

The tumultuous development of biotechnology has led to a wide diversification of cosmetic procedures. At the same time, costs for these treatments have been reduced, and consumer disposable income has increased. These factors, together with consumer perception (however erroneous it may be) that these services are common and safe, have driven exponential growth in demand.

2. Discussion

2.1. Definition of health

In this context, the elements that legitimate treatment for exclusively or prevalently cosmetic purposes are the different and more extensive definition of health accepted by the law and the scientific community [6], together with the commitment to provide correct, adequate, detailed and exhaustive information to the patient [7], and the operator’s possession of specific skills acquired through participation in specific formation and professional updating courses that include a focus on the psychological and ethical aspects connected with the type of healthcare treatment offered [8].

A purely objective vision of the concept of health, understood as the absence of illness and infirmity, has been abandoned, and there has been a valorization of the subjective component, such that health is defined as the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being,” as indicated in the preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization (effective April 7, 1948), understood as “interest of the collectivity,” ex. art. 32 of the Constitution of the Italian Republic (1948). The individual is requested to “fulfill irrevocable obligations of political, economic and social solidarity.”

The medical deontological code, since its 1995 version, and with greater cogency in successive ones, has defined health as the condition of “physical and psychological well-being of the person” [9], finding in this way full justification for healthcare procedures for exclusively cosmetic purposes in the care of the person’s psyche rather than just the person’s biology.

Analogously, the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights of December 7, 2000 (adopted December 12, 2007 with the Treaty of Lisbon), art. 3, says, “everyone has the right to respect for his or her physical and mental integrity.”

The broadening of the concept of health to a condition not necessarily linked to simple physical integrity but also requiring a state of complete psychological well-being is also shared by the guidelines of the jurisprudence of the Italian Court of Cassation which underlines the omni-comprehensive character of health, extending the connotation of subjectivity introduced by the World Health Organization to the “interior aspects of life as felt and lived by the subject in his or her experience” (Cass. Civ., S.U., sent. n. 17461/2006; Cass. Civ., Sez. I, sent. n. 21748/2007).

In this sense, procedures for the purpose of acquiring greater self-confidence and ease in relationships with others through the correction, improvement or modification of exterior appearance, independently of the existence of a real pathological etiology, are considered legitimate and legal [10].

Regarding cosmetic surgery, the National Bioethics Committee emphasizes the central importance of clear and exhaustive information suitable to the cultural and intellectual level of the patient, and the need to acquire the informed consent of the entitled party. It stresses the primary need to conduct a psychological evaluation of the patient before the treatment, and deems unacceptable the request for operations that are excessively invasive or uselessly risky compared to the benefits to be obtained, as the function of the organs involved is more important than the cosmetic result [11]. Psychological evaluation must focus on the comprehension and evaluation of the motivation for and expectations of the cosmetic medical treatment requested, given the usual high expectation of favorable results. In this way, on the one hand the patient is protected from emotional repercussions of an outcome different from that expected, with negative psychological ramifications. On the other hand, this evaluation should identify psychological and pathological conditions of the prospective patient that, by their very nature, would cause dissatisfaction with the results of the treatment, regardless of their objective nature, and subject the medical professionals to the risk of malpractice lawsuits.

It should also be noted that the healthcare professional has full, recognized authority to refuse a patient’s request for a treatment procedure that goes against the professional’s convictions or ethics [12].

This is strongly stated in Art. 22 of the recent medical deontology code (2016), “Refusal to perform a professional service,” which emphasizes the authority of the physician to “refuse to provide professional service when asked to perform procedures that conflict with his or her conscience or technical-scientific convictions, except in cases when such a refusal poses grave and immediate harm to the health of the person, and even in such a case, the physician must provide useful information and clarifications that enable the patient to receive the service.”

Similarly, deontological regulations are becoming increasingly more stringent. For example, there have been penal cases in which physicians were condemned for not refusing to do services requested by patients, when there was no valid technical motivation for the service.

2.2. The information in treatments for aesthetic purposes

In terms of the law, provision of information to the patient, beyond considerations of consent, is an integral part of the medical service whose purpose is to safeguard health. The lack of proper information is an automatic condition for professional liability for violation of the right to self-determination (Cass. Civ., Sez. III, sent. n. 2854/2015), which has particular importance in treatments for esthetic purposes (Cass. civ., III Sez., sent. n. 9705/1997).

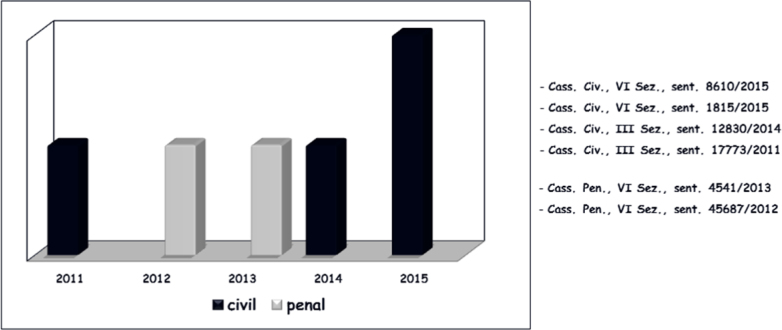

In the five-year period of 2011-2015, penal and civil jurisprudence of the Italian Court of Cassation has given constant attention to the proper provision of information in healthcare treatments for esthetic purposes, with sentences at least on an annual basis (Fig. 1), identifying the specific elements of information to be provided to the patient who chooses to undergo this type of procedure, and deeming illegal the acquisition of consent when proper information was lacking.

Figure 1.

The attention devoted by the jurisprudence of ligitimacy to the process of information in heathcare treatments of an cosmetic nature in five-year period from 2011 to 2015.

The information to be provided before operations for esthetic purposes should be exhaustive, detailed, unequivocal, easily understood, precise, specific, and should also include less statistically probable adverse events, given that the procedure is elective and there is no prognostic element that justifies limitations or caution in explanations [13].

In fact, deontological provisions indicate that the information (ex art. 33: Information and communication with the person assisted) must be understandable, exhaustive, appropriate to the patient’s capacity of comprehension, as well as his or her sensitivity and emotional reactivity; it should provide further information if requested by the patient, and, specifically in the case of cosmetic treatments (ex art. 76: Cosmetic and enhancement medicine), should neither elicit nor foster unrealistic expectations, and must take place before written consent.

It may also be opportune to provide the information in written form, in order to document the fact that the information was provided to the patient. Once this information has been provided to the patient, it is important to obtain the patient’s explicit expression of the decision to have the treatment [14], indicated with a signed consent form, in line with the dictates of deontological norms.

The National Committee for Bioethics (2012) underlined that in cases of cosmetic surgery, the patient must be informed about the modalities of the operation, the consequences to the state of health, the possible benefits and risks, and the results to be expected, compared to the subjective expectations of the patient. The Committee urged physicians to verify in detail just how much and precisely what part of the information provided has been fully acknowledged by the patient.

The patient must also be informed about the organization of the healthcare structure where the treatment will take place, in terms of the facilities, equipment or personnel that are lacking. This consideration is important, given the constant number of court cases in this regard.

The sentence of the Court of Cassation, III Civil Section, n. 18304/2011, is quite pertinent. It condemned the conduct of a physician who performed an oxygen-ozone anti-cellulite procedure on a woman who had previously had a hysterectomy and electrolipolysis, not only because it was an error to perform this procedure in her case, but also because the physician had failed to provide proper information about the deficiencies in the organization of the studio where the service was provided.

With specific reference to healthcare treatments for cosmetic purposes, over the years the law has expanded the expectations about the information to be provided to the patient. In fact, while in 2000 and the following years, it was expected that the patient should be given a realistic idea of the results possible, in relation to the needs of his or her professional and sentimental life, in more recent years the physician has been expected to explain in terms of logical and statistical probability the possibility of achieving an actual improvement in physical appearance, and to delineate the post-surgery results (Cass. Civ., Sez. II, sent. n. 4394/1985).

In other words, the physician is asked to foresee the results obtainable in the specific case. This obligation regarding results rather than means is in open contrast to the laws of biology, in which there is inter- and intra-individual, variability in the organism’s response to healthcare treatment. It is also in conflict with the subjective perception of the result that widely conditions the patient’s acceptance.

2.3. The healthcare advertising

The availability of means of communication (radio and television channels, internet, social networks, blogs, email, telephone messages, the press, scientific and popular magazines, journals, newspapers, and other organs of the press in general) that allow the real-time large-scale spread of messages that at times are ambiguous, or in any case capable of conditioning the human behavior and expectations of the recipients, makes the problems of the publication of healthcare information particularly acute and complex. This situation requires ethical and deontological reflection on the content of the information allowed, and also the means of communication that can be used [15].

Deontological provisions (articles 55 and 56) indicate that even though physicians are not prohibited from using any means of communication for promulgating healthcare news (always in the respect of the forms indicated by law 175/92 and Ministerial Decree 657/94), they are obliged to provide healthcare information that is accessible, transparent, rigorous, prudent, founded on scientific knowledge, truthful, correct, and appropriate to the object of the information. These provisions assign the Order responsible for the territory the task of assessing the truthfulness and exactness of news communicated by its members.

Healthcare advertising includes professional degrees and specializations earned, professional activity, characteristics of and fees charged for the services.

Comparative advertising is allowed if it uses measurable, certain clinical indicators that are accepted by the scientific community, to provide a comparison that is not deceptive and does not foster unfounded expectations or illusory hopes in citizens/patients.

Moreover, healthcare professionals must not advertise their own professional activity or promote their own services if they collaborate with government-run institutions or with private subjects in campaigns to inform or educate about health.

3. Conclusion

The Court of Cassation has also taken an increasingly severe position in relation to the violation of the patient’s right to self-determination, initially punished only when there was a worsening in the patient’s health conditions, independently of the correctness or incorrectness of the treatment performed, but later deemed liable to compensation for damages, when there are possible negative repercussions to the individual’s health, only because informed consent was not obtained for the healthcare procedure (Cass. Civ., Sez. III, sent. n. 5444/2006).

Moreover, on the basis of the more recent orientations in case law (Cass. Civ., Sez. III, sent. n. 12830/2014), if a cosmetic surgery results in a esthetic imperfection worse than the one to be eliminated or limited, even when the surgery was performed correctly, and the patient was not informed fully of the possible negative effects of the procedure, there is the presumption that consent would not have been given had the information been exhaustive, with the direct consequence of the admission of the liability of the physician for the harm thus derived.

Therefore, when the procedure is performed for cosmetic purposes, the Cassation affirms that in the presence of a defect of information, there is a presumed dissent by the patient; the Court deems it unnecessary to ascertain whether the patient would have undergone the healthcare treatment or not, because that lack of information in fact makes the medical act illegitimate.

This position leads one to deduce that the Court of Cassation considers treatments for cosmetic purposes to be superfluous procedures, and thus unnecessary, and as such illegitimate when there is a lack of proper information.

In the final analysis, the current orientation of the Court of Cassation regarding treatments for cosmetic purposes is 1) to deem them unnecessary if not even superfluous, in open contrast to the current extensive and subjective understanding of health, 2) to require a particularly weighty obligation to provide information, which includes not only indications about the actual improvement obtainable but also about the risks of worsening current cosmetic conditions and, in the presence of improper information about the outcomes of the treatment, 3) to presume that the patient does not agree to the treatment and open the possibility of the physician’s liability for damages caused, even independently of his or her performance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Bin P., Conti A., Buccelli C., Addeo G., Capasso E., Piras M.. Plastination: ethical and medico-legal considerations. Open Med. 2016;11(1):584–586. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Buccelli C., n Graziano V., Battimiello V., Paternoster M., Di Lorenzo P., Niola M.. Aesthetic dental procedures: Criticality of neuropsychological implications and quality of results [Gli interventi odontoiatrici a finalità estetica: criticità degli aspetti psicologici e di qualità di risultati] Conf. Cephalal. et Neurol. 2017;27(2):72–78. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pinchi V., Focardi M., Norelli G.A.. Deontologia ed etica in chirurgia plastica: una analisi comparativa. Riv. It. Med. Leg. 2010;6:903–941. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bin P., Delbon P., Piras M., Paternoster M., Di Lorenzo P., Conti A.. Donation of the body for scientific purposes in Italy: ethical and medico-legal considerations. Open Med. 2016;11(1):316–320. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Swami V.. et al. Looking good: factors affecting the likelihood of having cosmetic surgery. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2008;30:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Piras M., Delbon P., Conti A., Graziano V., Capasso E., Niola M., Bin P.. Cosmetic surgery: medicolegal considerations. Open Med. 2016;11(1):327–329. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ferrarese A., Pozzi G., Borghi F., Pellegrino L., Di Lorenzo P., Amato B., Santangelo M., Niola M., Martino V., Capasso E.. Informed consent in robotic surgery: quality of information and patient perception. Open Med. 2016;11(1):279–285. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ferrarese A., Buccelli C., Addeo G., Capasso E., Conti A., Amato M., Compagna R., Niola M., Martino V.. Excellence and safety in surgery require excellent and safe tutoring. Open Med. 2016;11(1):518–522. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].FNOMCeO, Codice di Deontologia Medica. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bilancetti M. La responsabilità penale e civile del medico. Cedam Press; Padova: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Aspetti bioetici della Chirurgia estetica e ricostruttiva. Vol. 21. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri; Roma: 2012. Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica. giugno. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Piras M., Delbon P., Bin P., Casella C., Capasso E., Niola M., Conti A.. Voluntary termination of pregnancy (medical or surgical abortion): forensic medicine issues. Open Medicine. 2016;11(1):321–326. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Laino A., Deli R., Savastano C., D’ Alessio R., Buccelli C. L’ortodonzia è funzione o estetica? Implicazioni medico legali. Ortodonzia, Legge e Medicina legale: la responsabilità odontoiatrica e i rapporti di attività professionale in ortodonzia. Martina Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Borello A., Ferrarese A., Passera R., Surace A., Marola S., Buccelli C., Niola M., Di Lorenzo P., Amato M., Di Domenico L., Solej M., Martino V.. Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Open Med. 2016;11(1):564–573. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Buccelli C., Niola M., Laino A., Di Lorenzo P. Etica, deontologia e professione in odontoiatria. Ortodonzia, Legge e Medicina legale: la responsabilità odontoiatrica e i rapporti di attività professionale in ortodonzia. Martina Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]