ABSTRACT

Background: Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is increasingly recognized as an important cause of myocardial infarction and sudden death. Although some correlations have been noted in relation to aetiology, no direct causes have been identified in a large number of patients. Most of the patients are women in peripartum period or of childbearing age, with few if any risk factors for coronary heart disease. In men, however, risk factors for atherosclerosis are more prevalent in cases of SCAD

Case report: We report a case of a 43-years-old healthy male, with no known risk factors, who presented with ischemic chest pain and elevated troponin levels. He underwent an emergent percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography which revealed a total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery at its origin with an evidence of spontaneous dissection as the cause of the occlusion, which was subsequently treated with placement of a drug-eluting stent and thrombectomy from the distal occluded portion. This case highlights the importance of including spontaneous coronary artery dissection as a cause of ischemic cardiac insults and illustrates the approach to treatment.

Conclusion: Internists should have a low threshold of clinical suspicion for SCAD especially in a young patient with no known risk factors and should know the importance of emergency in management.

KEYWORDS: Coronary artery dissection, coronary artery disease, coronary angiography, chest pain

1. Introduction

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is defined as a non-traumatic and non-iatrogenic separation of the coronary arterial wall. It is increasingly recognized as an important cause of myocardial infarction and sudden death. We report a case of a young healthy male, with no known risk factors, who presented with acute anterior wall myocardial infarction secondary to SCAD, Which could constitute a challenge in regards to diagnosis and treatment.

2. Case description

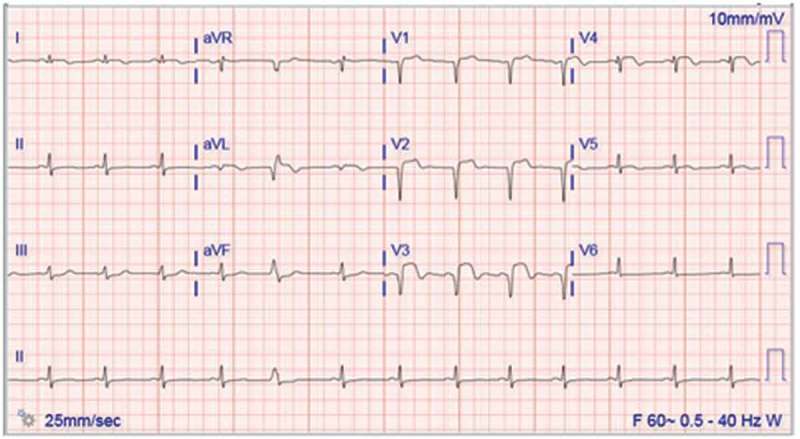

A 43-year-old healthy male with no significant risk factors presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with acute onset of substernal, pressure-like, non-radiating chest pain of moderate intensity, associated with shortness of breath and nausea that started while he was exercising at a jiu-jitsu class. He has no personal history of similar complaints or known medical problems. He also denied a family history of sudden death, strokes or congenital heart disease. He initially visited the urgent care clinic, where his troponin was critically elevated and he was transferred to our facility urgently. On presentation, his vital signs were stable with benign physical exam including cardiac and respiratory exams. The initial electrocardiogram (EKG) was significant for ST-segment elevations in the anterior leads (Figure 1). Initial troponin at the urgent clinic was 93.6 ng/ml, which trended up to 217.4 ng/ml by the time he arrived at the ED. urine drug screen was negative.

Figure 1.

Resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (EKG) showing ST elevation in the anterior leads V2, V3 and V4.

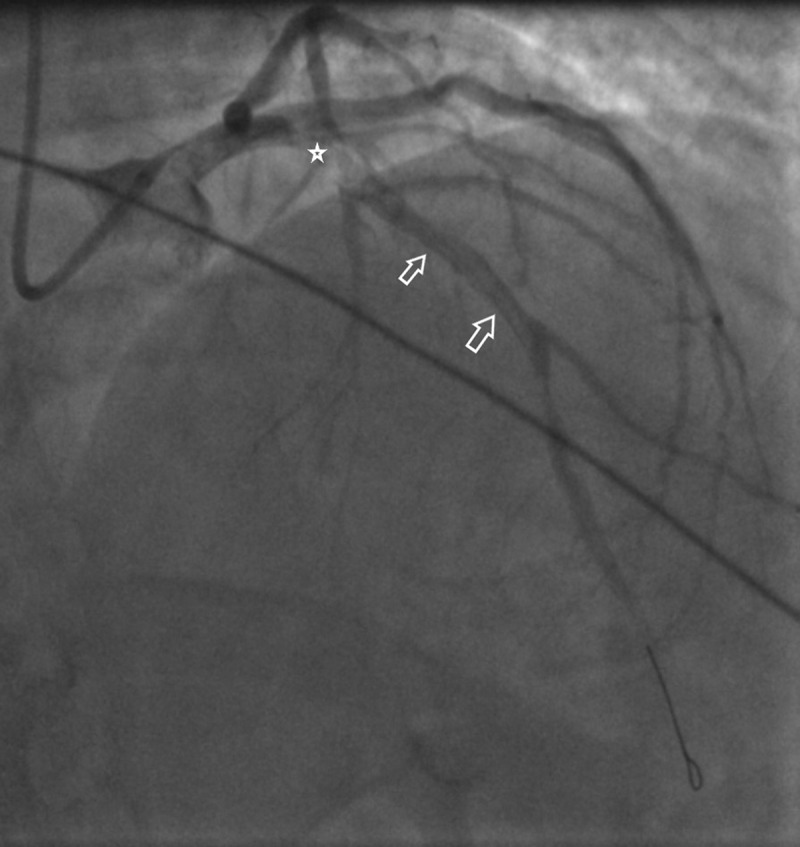

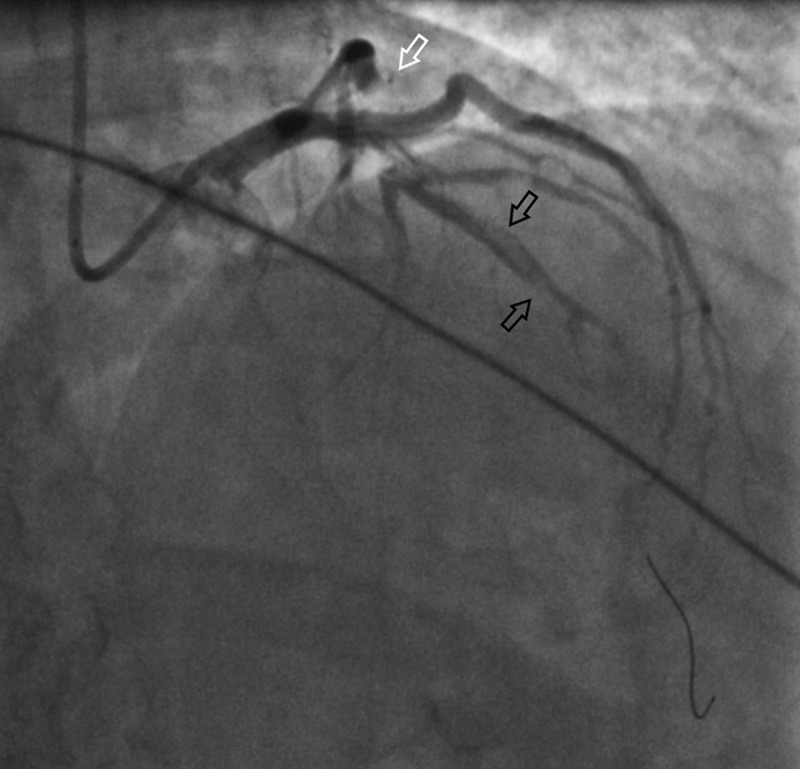

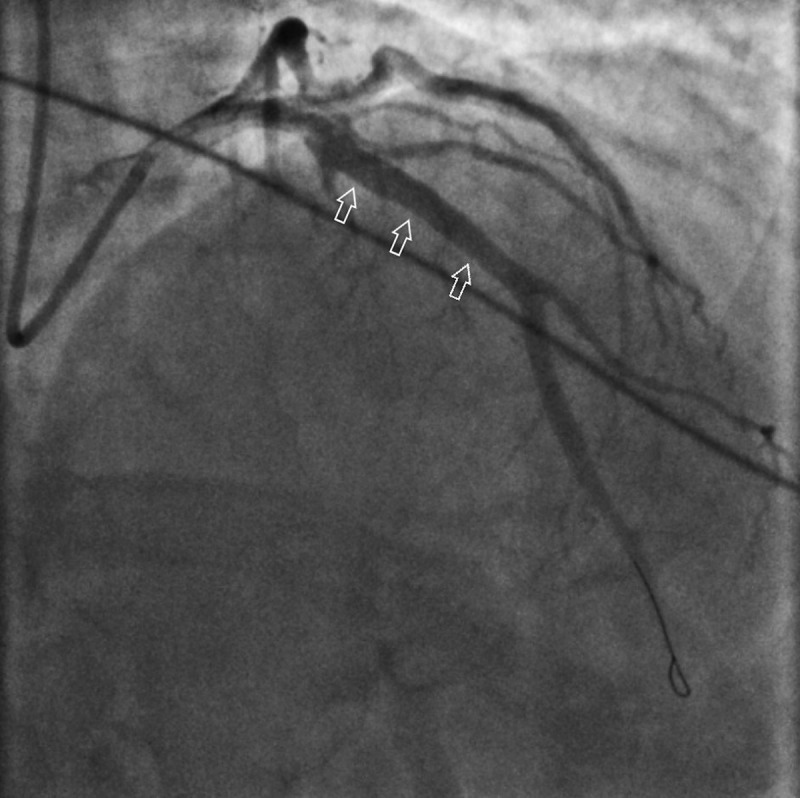

Emergent coronary angiography revealed total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery at its origin (LAD) with an evidence of spontaneous dissection as the cause of the occlusion (Figures 2 and 3). The right coronary artery was patent and free of disease. Left ventriculogram revealed severe left ventricular dysfunction with elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and akinesis of the mid to distal anterior wall and apex. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was estimated at 41%. An apical thrombus was also discovered during echocardiogram. The LAD occlusion was successfully treated with primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and placement of a drug-eluting stent (4.0 × 38 mm Xience Alpine stent, Figure 4). Post-intervention there was still an evidence of thrombosis in the obtuse marginal artery and the diagonal artery which was addressed with aspiration thrombectomy. The procedure was uneventful with complete resolution of the chest pain thereafter.

Figure 2.

Coronary angiogram showing coronary artery dissection that starts at the origin of Left Anterior descending artery (LAD) (See the star) and extends down to involve proximal and Mid LAD (See the white arrows).

Figure 3.

Coronary angiogram showing occlusion of the proximal branch of the Left anterior descending artery (LAD) (See the white arrow) and an evidence of proximal and Mid LAD dissection (See the black arrows).

Figure 4.

Coronary angiogram post percutaneous coronary angioplasty and placement of drug-eluting stent to the left anterior descending artery (See white arrows).

Transthoracic echocardiogram 2 days post procedure showed persistent akinesis of the anterior wall and LVEF of 40%. He was treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and prasugrel), rosuvastatin, metoprolol, lisinopril, and warfarin. He was discharged home in stable condition. No recurrence of his symptoms was reported in follow up post-discharge.

3. Discussion

SCAD is increasingly recognized as an important cause of myocardial infarction. It was first described in 1931 in a 42-year-old white woman who died suddenly after experiencing chest pain [1]. It is defined as a non-traumatic and non-iatrogenic separation of the coronary arterial wall. The mechanism of non-atherosclerotic SCAD is not fully understood, but an intimal tear or bleeding of vasa vasorum with intermedial haemorrhage has been proposed, with both resulting in the creation of a false lumen filled with intramural hematoma [2,3]. It was thought to be a rare cause of ACS with a prevalence of 0.2–1.1% based on coronary angiographic findings. However, a recent contemporary review suspect that the true prevalence in patients presenting with ACS might be as high as 1.7–4% on the basis of moderate series [4,5]. SCAD affects women in more than 90% of the cases, and with the exclusion of the atherosclerotic cases, women constitute up to 95% of the cases [4,6–8]. In men, however, the atherosclerotic entity is more prevalent [9]. In most cases, a predisposing arterial disease association or cause is identified; however, up to 20 percent of cases are labelled as idiopathic. Potential predisposing factors include fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), postpartum status, multiparty, connective tissue disorders, and hormonal therapy [6–8,10]. Precipitating stressors such as intense exercise or emotional stress, labour and delivery, intense Valsalva-type activities, or recreational drug uses were reported as a provoking factor of the acute coronary event in over 50 percent of cases in a contemporary series [6]. Of note, our patient has no risk factor for atherosclerosis nor any predisposing factor.

Clinically, almost all patients with SCAD presents with ACS, either ST-elevation myocardial infarction or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Ventricular arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock or sudden cardiac death could complicate a small proportion of cases. Coronary angiography is the first-line modality for diagnosis, although with some limitations. A more accurate method of diagnosis is dedicated intracoronary imaging such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), However availability, additional risks and cost are limiting factors. Based on angiographic findings, the lesion is graded into three types [11]:

Type 1: Characterized by a longitudinal filling defect, representing the radiolucent intimal flap, which appears as a double lumen, with a prevalence of 29%.

Type 2: The most common occurring in 67% of the cases. It is characterized by diffuse long smooth tubular lesions (due to intramural hematoma) with no visible dissection plane that can result in complete vessel occlusion.

Type 3: Rare, occurring in 4% of cases. Characterized by multiple focal tubular lesions due to intramural hematoma that mimics atherosclerosis.

Regarding management, it remains highly controversial especially in regards to the value of coronary revascularization over a conservative medical management [12,13]. Conservative management is preferred in stable patients with SCAD as most dissected segments will heal spontaneously [9]. Generally, initial treatment is similar to standard ACS patients with the use of dual antiplatelet agents, heparin, and beta-blockers to preserve patency of the true lumen and prevent thrombotic occlusion. Indications for revascularization includes: complete vessel occlusion with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 0 flow which is unlikely to resolve with medical treatment alone, left main stem involvement, ongoing ischemia, recurrent chest pain, hemodynamic instability and sustained ventricular arrhythmias. In patients who fail PCI or have a coronary anatomy not suitable for PCI, emergent CABG should be considered. CABG should also be considered for patients with left main dissections or with extensive dissections involving proximal arteries.

Prognostically, acute outcomes are considered good. In-hospital mortality was less than 5% based on some series, while the rate of recurrent MI or development of other major adverse cardiovascular outcomes (MACEs) were 5–10%. Long-term complications post-discharge, however, were significantly higher. Recurrence of SCAD was reported in approximately 15% at 2-year follow up [7]. Subacute MACEs were reported in up to 20% during the same follow-up period. The rate of MACEs increases proportionally with time, reported to be in 50% at 10-year follow-up period [7,8,14]. The high long-term MACEs rates emphasize the importance of close follow up of SCAD patients with a specialized cardiovascular specialist.

4. Conclusion

SCAD is an infrequent cause of ACS in young patients with no classical risk factors for atherosclerosis. Predisposing risk factors include FMD, connective tissue disorders, emotional stress and hormonal therapy. Conservative management strategy is favoured in stable patients with good acute in-hospital outcomes. However, intervention is indicated in those with persistent chest pain or unstable vitals. Thus, a low threshold of suspicion should be maintained in identifying this subgroup of patients to implement the timely and proper management. Given the long-term recurrence rate of SCAD and the frequency of MACEs, close follow up with cardiovascular specialists is utmost for all SCAD patients and further studies are needed to formulate treatment guidelines and to improve the outcomes.

Funding Statement

The authors have not received any funding for this publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Robert Dickinson Swackhamer from the Department of Cardiology in their expertise in taking care of the patient.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Pretty HC.Dissecting aneurysm of coronary artery in a woman aged 42: rupture. Br Med J. 1931;1:667. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Alfonso F. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: new insights from the tip of the iceberg? Circulation. 2012;126:667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Alfonso F, Bastante T. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: novel diagnostic insights from large series of patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:638–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rashid HN, Wong DT, Wijesekera H, et al. Incidence and characterisation of spontaneous coronary artery dissection as a cause of acute coronary syndrome - a single-centre Australian experience. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:336–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nishiguchi T, Tanaka A, Ozaki Y, et al. Prevalence of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saw J, Ricci D, Starovoytov A, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: prevalence of predisposing conditions including fibromuscular dysplasia in a tertiary center cohort. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012;126:579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Alfonso F, Paulo M, Lennie V, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: long-term follow-up of a large series of patients prospectively managed with a “conservative” therapeutic strategy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Adès LC, Waltham RD, Chiodo AA, et al. Myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery dissection in an adolescent with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV due to a type III collagen mutation. Br Heart J. 1995;74:112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Saw J. Coronary angiogram classification of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Catheterization Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84:1115–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jorgensen MB, Aharonian V, Mansukhani P, et al. Spontaneous coronary dissection: A cluster of cases with this rare finding. Am Heart J. 1994;127:1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hering D, Piper C, Hohmann C, et al. Prospective study of the incidence, pathogenesis and therapy of spontaneous, by coronary angiography diagnosed coronary artery dissection. Zeitschrift Für Kardiologie. 1998;87:961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lettieri C, Zavalloni D, Rossini R, et al. Management and long-term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]