Abstract

This qualitative systematic review examined interventions that promote linkage to or utilization of HIV care among HIV-diagnosed persons in the United States. We conducted automated searches of electronic databases (i.e., MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL) and manual searches of journals, reference lists, and listservs. Fourteen studies from 19 published reports between 1996 and 2011 met our inclusion criteria. We developed a three-tier approach, based on strength of study design, to evaluate 6 findings on linkage to care and 18 findings on HIV care utilization. Our review identified similar strategies for the two outcomes, including active coordinator’s role in helping with linking to or utilizing HIV care; offering information and education about HIV care; providing motivational or strengths-based counseling; accompanying clients to medical appointments and helping with appointment coordination. The interventions focused almost exclusively on individual-level factors. More research is recommended to examine interventions that address system and structural barriers.

Keywords: HIV care utilization, linkage to care, retention in care, HIV/AIDS, people living with HIV, qualitative systematic review

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1995, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has allowed many people diagnosed with HIV to lead healthy and productive lives. To maximize the benefits of HAART, it is important that HIV-diagnosed persons be linked to and retained in HIV primary medical care [1–4]. Earlier entry into and better utilization of HIV care have been shown to reduce risk of developing HIV opportunistic infections [5]; increase survival rates [2, 6]; improve access to psychosocial and preventive services which promotes continuity of medical care [7]; and improve overall quality of life [8]. Additionally, evidence from San Francisco [9] and British Columbia [10] indicates that the expansion of HAART coverage is associated with decreases in community viral load and reductions in new HIV diagnoses in those communities. The most direct evidence of early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for preventing HIV transmission is from the randomized controlled trial of the HPTN Study 052 that showed an impressive 96% reduction in HIV transmission risk in HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples [11].

Despite the individual- and population-level benefits of HIV care and treatment, a considerable number of people diagnosed with HIV in the United States are not receiving HIV medical care. A recent meta-analytic review estimated that 69% of HIV-diagnosed persons entered primary medical care soon after diagnosis and that 59% of HIV-diagnosed persons had two or more HIV medical visits in a 12-month interval [12]. The estimated percentage of HIV-infected persons in the United States who were diagnosed with HIV, then linked and retained in HIV care, received treatment, and have successfully achieved viral suppression ranges from only 19% to 29% [13–15]. Hence, there is considerable room for improvement in all phases of the continuum of HIV care.

Several barriers may prevent HIV-diagnosed persons from entering into HIV care. These include avoidance and disbelief of HIV serostatus, and negative experiences with, and distrust of, health care [16], not feeling sick [17], and having concerns about privacy [18]. A separate set of barriers may prevent persons with HIV from utilizing HIV medical care, including unstable housing [19, 20], lack of child care or transportation [21], discomfort in engaging with medical providers [22–24], HIV stigma [25], negative perceptions of the health care system [26, 27], misperception that health insurance coverage is necessary [28, 29], limited social support [30], competing caregiver responsibilities [31], and competing unmet needs such as mental health or drug addiction [32]. With the National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) calling for increasing access to HIV care and improvement of health outcomes for persons with HIV [4], it is important to identify effective prevention strategies that eliminate barriers and facilitate HIV-diagnosed persons’ entry into and utilization of HIV medical care.

The purpose of this systematic review is to locate and qualitatively evaluate interventions designed to promote linkage to and ongoing utilization of HIV care among HIV-diagnosed persons in the United States. A recent publication [33] by an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel (IAPAC) has systematically searched the literature for entry to care, retention in care, and ART adherence and provided mostly recommendations on medication adherence from the available evidence from the literature. Differing from the general IAPAC guidelines, our review provides a more in-depth evaluation of each intervention and its effect on linkage to care or HIV care utilization outcome and includes more recently published evidence. Our specific goals are threefold: determine the types and strengths of the interventions tested, demonstrate specific strategies that promote linkage and utilization of HIV care, and determine what research gaps and programmatic recommendations can be obtained from the studies reviewed.

Methods

Database and Search Strategy

We used the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs) project’s cumulative HIV/AIDS/STI prevention database [34]). Two librarians with substantial systematic search experience developed a comprehensive search strategy that included automated and manual searches. The automated search was conducted in October, 2011 and updated in May, 2012 to identify reports published between January, 1996 and December, 2011. The automated search was implemented in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO [35–38] by cross-referencing multiple search terms (i.e., index terms, keywords, and proximity terms) in three areas: HIV-positive persons; prevention/intervention/evaluation; and health care utilization descriptors (e.g., care access and utilization, linkage, retention). No language restriction was applied to the automated search. As required by the PRISMA checklist [39], the full search strategy of the MEDLINE database is provided in the appendix. The searches of the other databases are available from the corresponding author. The manual search consisted of checking reference lists of pertinent articles and examining HIV/AIDS Internet listservs (i.e., adherence@ghdonline.org; www.RobertMalow.org) and other government-funded projects and programs listed on the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) website (http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/special/spnsproducts.html).

Study Selection

Studies were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) conducted in the United States after HAART became available in 1995; (2) main goal or one of the study goals was to promote linkage to HIV care or HIV medical care utilization among HIV-diagnosed persons; (3) studies that provided statistical tests of intervention effects or only provided descriptive data without providing statistical tests of intervention effects; and (4) linkage to care or HIV care utilization outcomes (defined below) were reported.

For this review, we broadly defined linked to HIV care as entry into care among persons newly or previously diagnosed with HIV infection who had either never entered care, or had entered care but dropped out as defined in the original study. HIV care utilization is broadly defined to capture a range of outcomes depending on the focus and intent of the original study. For some studies, HIV care utilization outcomes reflect retention (e.g., two HIV care visits in a 6-month period, an HIV care visit every 3 or 4 months) among persons who were already linked to HIV care. Other studies did not specifically indicate whether study participants were already linked to HIV care at the time of assessment. For those studies, the HIV care utilization outcomes reflect the proportion of participants who had a care visit at the time of assessment regardless of their previous care history.

Studies were excluded if the outcome focused on utilization of case management rather than HIV primary care [40–42]; emergency or inpatient hospitalization [43]; or general health care utilization and not HIV-specific care [44–47]. We did not include HIV testing programs in communities or in clinic settings because the studies often did not include sufficient information describing linkage strategies [48–50].

Data Abstraction

Once the eligible studies were identified, standard qualitative research methods were used to collect pertinent data [51]. Two studies (HRSA SPNS Outreach initiative and HRSA SPNS Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color) [52, 53] produced multiple published reports (Table 1). One publication reported the findings of two separate interventions [21]. In addition, some publications provided both linkage to care and HIV care utilization outcomes. We coded the findings separately for each outcome. We also treated the finding (either a linkage to care or HIV care utilization outcome) in each published report independently because the finding often focused on different populations (e.g., newly diagnosed or not fully engaged in care), examined different intervention strategies, used part of the pooled data from multi-sites or individual site data, or evaluated the intervention effect with different study methods.

Table 1.

Study, Participant, and Design Characteristics (14 Intervention Studies from 19 Published Reports)

| Study Name | First Author (Publication Year), Study Dates, and Location of Study |

Target Population, Percent Female, Persons of Color (POC) or Gay/Bisexual (GB) |

Income or Housing Status, % Drug User, % Mental Health Diagnosis |

HIV Disease Status, Health Insurance |

Type of Design, Data Collection Method |

Intervention Period, Assessments, Analytic Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTAS | Gardner (2005) [60], 3/01–5/02, Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; Miami, FL; Los Angeles, CA |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARTAS II | Craw (2008) [58], 4/05–10/06, Anniston, AL; Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; Baton Rouge, LA; Chicago, IL; Columbia/Greenville, SC; Jacksonville, FL; Kansas City, MO; Miami, FL; Richmond, VA |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bilingual/Bicultural Health Care Team | Enriquez (2008) [59], 3/05–3/07 Kansas City, MI |

|

NR for all 3 variables |

|

|

|

| Bridge Project for APIs | Chin (2006) [56], 6/97-3/01, New York City, NY |

|

NR for all 3 variables |

|

|

|

| Bridge Project for HIV-diagnosed ex-offenders | Rich (2001) [66], 1/97 – 6/00, Providence, RI |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bridge Project for HIV-diagnosed ex-offenders II | Zaller (2008) [70], 5/03 – 12/05, Providence, RI |

|

|

|

|

|

| BRIGHT | Wohl (2011) [68], Study dates NR, North Carolina |

|

|

|

|

|

| California Bridge Project | Molitor (2006) [62], 3/01–12/03, California - 21 sites |

|

|

NR for both variables |

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Bradford (2007) [55], 10/03-6/06, Portland, OR; Seattle, WA; Boston, MA; Washington, DC |

|

|

|

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Coleman (2009) [57], 10/03 - 6/05, Seattle, WA; Portland OR; Los Angeles, CA; Detroit, MI; Washington DC; New York City, NY; Providence, RI; Boston, MA; Miami, FL (data from 1 above site not used because no newly diagnosed HIV+ persons) |

|

|

|

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Naar-King (2007) [63], study dates NR, Portland, OR; Detroit, MI; Washington, DC; Los Angeles, CA |

|

|

|

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Hightow-Weidman (2011) [52], 6/06 – 8/09, Bronx, NY; Chapel Hill, NC; Chicago, IL; Detroit, MI; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Oakland, CA; Rochester, NY |

|

|

|

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Hightow-Weidman (2011) [61], 6/06–9/09, North Carolina |

|

|

|

|

|

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Wohl (2011) [67], 4/06 – 4/09, Los Angeles, CA |

|

|

Mean CD4 = 397 NR for Health Insurance |

|

|

| Housing and Health Study | Wolitski (2010) [69], 7/04-1/07, Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA |

|

|

|

|

|

| INSPIRE | Purcell (2007) [65], 8/01-3/05, New York, NY; San Francisco, CA; Miami, FL; Baltimore, MD |

|

|

NR for both variables |

|

|

| LIGHT | Andersen (1999) [54], 10/97-6/98, Detroit, MI |

|

|

NR for both variables |

|

|

| Youth-Focused Motivational Interviewing (MI) | Naar-King (2009) [64], 03–06, Detroit, MI |

|

|

NR for both variables |

|

|

NR = not reported; ARTAS = Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study; BRIGHT = Bridges to Good Health and Treatment; HRSA SPNS Outreach = HRSA SPNS Outreach Initiative; HRSA SPNS MSM of Color = HRSA SPNS Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color; INSPIRE = Interventions for Seropositive Injectors—Research and Evaluation

For each published report, we coded study characteristics (e.g., study location and dates, study design, sample size, data collection method, research design), participant characteristics (e.g., target population, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, income, housing status, drug use, mental health diagnosis, health insurance status, HIV disease status), intervention characteristics (e.g., intervention focus, components, delivery method, and duration), and outcome measures.

We also coded a-priori intervention categories that included: accompanying a client to a medical appointment; ancillary services (e.g., child care, nutrition supplementation, food vouchers, clothing, emergency financial assistance, housing, drug treatment, and mental health services); appointment coordination (e.g., scheduling, reminders, follow-up on missed appointments); case management (e.g., active coordinator’s role in helping with linking to or utilizing HIV care); co-location of care and services (offering service at the same facility as HIV-diagnosed persons received HIV primary care); culturally-specific strategies and language interpretation; establishing formal links between agencies; home-based services; media; outreach; counseling and psychosocial support strategies (e.g., providing information or education, counseling, building relationships, providing emotional support, assessing client’s strengths); and transportation services (e.g., provide shuttle service or subway/bus token). Trained reviewers worked independently to extract the relevant data using a standardized abstraction form. Each relevant published report was coded by 2 reviewers. The overall agreement of independent codes among the reviewers was 96% with a kappa rate of 80%. Discrepancies were resolved through reviewer discussion.

Three-tier Framework Used in Evaluating Intervention Effect

Studies were heterogeneous in sample characteristics, study designs, type of interventions, and outcome measures. A meta-analysis was not performed because calculating pooled effects would not be appropriate due to heterogeneity across studies. Instead, we developed a hierarchical three-tier approach after multiple internal and external consultations with HIV researchers to evaluate evidence with varying study designs. This tier system is based on the rigors of research design as well as the strength of findings. Tier I evidence refers to a statistically significant intervention effect (i.e., p < .05) based on the between-group comparison from a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Tier II evidence refers to a statistically significant effect (i.e., p <.05) based on (a) a comparison between the post-intervention outcome data of an intervention group and the outcome data of a historical control group; or (b) a pre- and post-intervention analysis of a serial cross-sectional or longitudinal cohort. Tier III evidence is based on the comparison of post intervention data against Marks et al’s meta-analysis findings [12] – that is, exceeding 69% of newly HIV-diagnosed study participants who were linked to care after receiving an intervention (i.e., linkage to care cut-off point) or exceeding 59% of study participants who had at least two primary HIV care visits within a specified time period (i.e., retention in care cut-off point). Findings that were not reported as described above could not be evaluated using our tiered framework.

Results

Study Characteristics

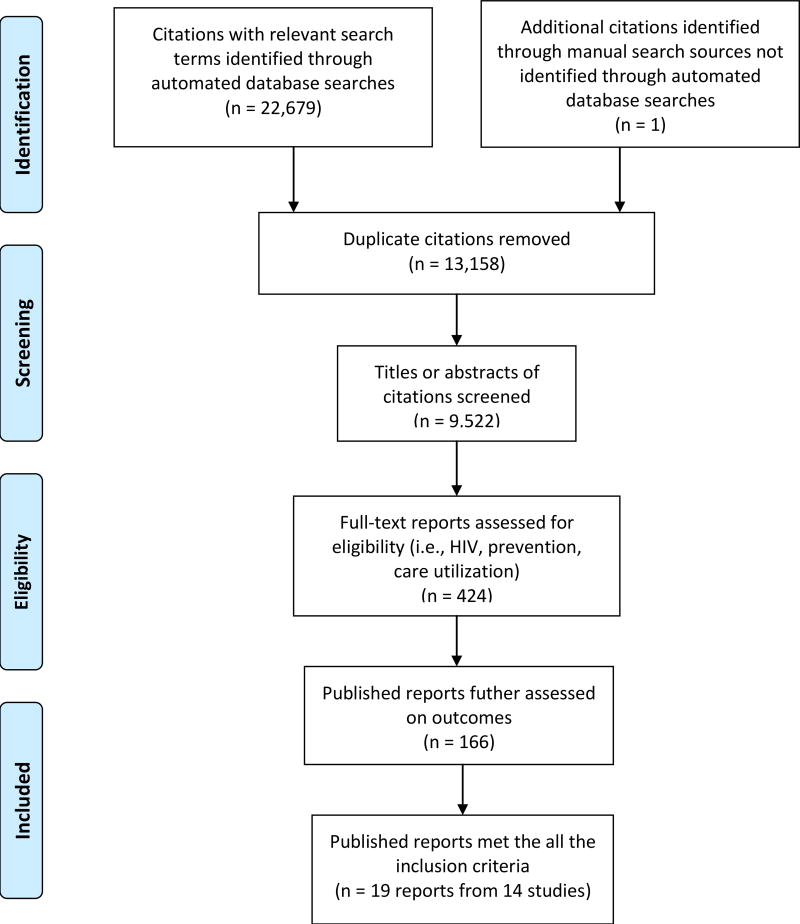

A total of 9,522 abstracts were screened, with 166 full published reports obtained and reviewed for further examination. Nineteen published reports [21, 52, 54–70] met the eligibility criteria and these comprised of 14 different intervention studies.

Table 1 displays the study, participant, and design characteristics of the published reports. Five focused on persons newly diagnosed [52, 57, 58, 60, 63], one on solely or partially out-of-treatment HIV-diagnosed persons [62], and four of those who were in intermittent HIV care [52, 55, 61, 67]. Three were specifically designed to bridge HIV care for ex-offenders after they were released to communities [66, 68, 70]. The remaining published reports did not clearly indicate whether participants had previously entered HIV primary care or not [21, 54, 56, 64, 65, 69]. Across published reports, racial and ethnic minority participants ranged from 62% to 100% and gay or bisexual participants ranged from 12% to 100%. One published report specifically targeted homeless HIV-diagnosed persons [69] while 13 others indicated that 10% to 80% of participants did not own or rent property, or lived in unstable housing situations. A majority of HIV-diagnosed participants reported income levels of $10,000 or less per year (range: 62%–100%). The percentage of study participants with health insurance ranged from 34% to 96%.

In terms of study design, five [60, 64, 65, 68, 69] of the 14 studies were RCTs. About half of the studies evaluated outcomes with small sample sizes (i.e., < 100 participants in the intervention arm) and all were based on convenience samples. Interventions varied substantially in the term of intensity: some only offered case management contacts up to five times in 90 days [58, 60], while others offered multiple-component interventions and on-going case management over a 12-month intervention period [21]. Common post-baseline measurement time points ranged from 3, 6, 9, to 12 months. The outcome assessments were usually based on medical records or self-report.

Findings on Linkage to Care Outcomes

As seen in Table 2, six findings reported on linkage-to-care outcomes and five of the six findings can be evaluated with our three-tier framework. These five findings focused on newly diagnosed persons and clustered around two major projects: ARTAS (original and ARTAS-II) and the HRSA-SPNS related studies. All five findings showed evidence of improving the percentage of newly diagnosed persons entering into HIV care after the intervention. Among these findings, the strongest evidence came from one RCT [60] that used a time-limited strength-based case management strategy for linking newly diagnosed persons to care. Intervention participants were significantly more likely than control participants to visit a HIV clinician within six months of enrolling in the intervention. The remaining four findings [52, 57, 58, 63] were evaluated with the Tier III criterion. The percentage of newly diagnosed persons who were entered into HIV care within 3 or 6 months of study entry ranged from 78% to 92%, all of which exceeded the Tier III criterion (i.e., > 69%).

Table 2.

Summary of Intervention Strategies and Findings on Linkage to Care Outcomes (6 Findings)

| Study Name |

First Author (Year) |

Intervention Strategies | Findings | Significance and Evidence? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTAS | Gardner (2005) [60] |

|

Yes; Tier I | |

| ARTAS II | Craw (2008) [58] |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| California Bridge Project | Molitor (2006) [62] |

|

Indeterminatei | |

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Hightow-Weidman (2011) [52](7 sites) |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach | Naar-King (2007) [63] |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Coleman (2009) [57] |

|

|

Yes, Tier III |

ARTAS = Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study

BRIGHT = Bridges to Good Health and Treatment

HRSA SPNS Outreach = HRSA SPNS Outreach Initiative

HRSA SPNS MSM of Color = HRSA SPNS Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color

INSPIRE = Interventions for Seropositive Injectors—Research and Evaluation

Intervention Strategies

= Accompany to appointments

= Ancillary services

= Appointment coordination/reminders/follow-up if appointment missed

= Case management

= Co-location of services

= Outreach

= Counseling and psychosocial support strategies (e.g., counseling, relationship building, providing knowledge, emotional support)

= Transportation

Findings

= post data only and Marks’ meta-analysis estimate for linkage cannot apply as study participants were not newly diagnosed patients

Although there were a variety of intervention components for all five findings that showed linkage to care improvements, two most common components that were consistently found throughout all five findings were case management that helped clients to navigate complex medical care systems and counseling and psychosocial support strategies that included building relationships, identifying client strengths, counseling, and providing information and education. Accompanying clients to appointments [57, 58, 60] and coordinating appointments for clients [52, 57] were also strategies used in some interventions.

The one finding that could not be evaluated with one of the three tiers was focused on out-of-care HIV-diagnosed persons [62]. Before the intervention, time without medical care for the study participants averaged 535.4 days (17.8 months). Fifteen months after the study entry, 29% of this hard-to-reach group entered into HIV medical care. This particular finding used similar strategies that were used by the other five significant findings, such as appointment accompaniment and case management.

Findings on HIV Care Utilization Outcomes

As seen in Table 3, 18 findings reported HIV care utilization outcomes and 11 of 18 can be evaluated by the three-tier framework. Eight of the 11 findings (73%) showed evidence of improving HIV care utilization among HIV-diagnosed persons. Among the eight findings that showed significant improvement, the strongest evidence came from one RCT [60] that focused on promoting initial entry into care, but also reported a retention-in-care outcome. Persons who received the strength-based intervention were significantly more likely to have HIV care visits in each of the two consecutive 6-month periods. For the remaining findings that demonstrated evidence, three indicated Tier II evidence [55, 59, 61] and four demonstrated Tier III evidence [52, 57, 63, 67].

Table 3.

Summary of Intervention Strategies and Findings on HIV Care Utilization Outcomes (18 Findings)

| Study Name | First Author (Year) |

Intervention Strategies | Findings | Significance and Evidence? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTAS | Gardner (2005) [60] |

|

Yes, Tier I | |

| Bilingual/Bicultural Health Care Team | Enriquez (2008) [59] |

|

|

Yes, Tier II |

| Bridge Project for APIs | Chin (2006) [56] |

|

|

Indeterminatem |

| Bridge Project for HIV-diagnosed ex-offenders | Rich (2001) [66] |

|

|

Indeterminaten |

| Bridge Project for HIV-diagnosed ex-offenders II | Zaller (2008) [70] |

|

|

Indeterminaten |

| BRIGHT | Wohl (2011) [68] |

|

No, Tier I | |

| INSPIRE | Purcell (2007) [65] |

|

|

No, Tier I |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Bradford (2007) [55] |

|

|

Yes, Tier II |

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Hightow-Weidman (2011) [61](NC site) |

|

Yes, Tier II | |

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Hightow-Weidman (2011) [52](7 sites) |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| HRSA-SPNS MSM of Color | Wohl (2011) [67] |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Coleman (2009) [57] |

|

|

Yes, Tier III |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach | Naar-King (2007) [63] |

|

Yes, Tier III | |

| HRSA-SPNS Outreach Initiative | Andersen (2007) [21] Intervention 1: Transportation only |

|

Indeterminatem | |

| Intervention 2: Transportation plus |

|

Indeterminatem | ||

| Housing and Health Study | Wolitski (2010) [69] |

|

No, Tier I | |

| LIGHT | Andersen (1999) [54] |

|

Indeterminateo | |

| Youth-focused Motivational Interviewing | Naar-King (2009) [64] |

|

|

Indeterminatep |

ARTAS = Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study

BRIGHT = Bridges to Good Health and Treatment

HRSA SPNS Outreach = HRSA SPNS Outreach Initiative

HRSA SPNS MSM of Color = HRSA SPNS Outreach, Care, and Prevention to Engage HIV Seropositive Young MSM of Color

INSPIRE = Intervention for Seropositive Injectors – Research and Evaluation

Intervention Strategies

= Case Management

= Counseling and psychological support strategies (e.g. counseling, relationship building, providing knowledge, emotional support)

= Accompany to appointments

= Culturally-specific strategies/language interpretation

= Home-based services

= Co-location of services

= Outreach

= Ancillary services

= Establishing formal links between agencies

= Transportation

= Appointment coordination/reminders/follow-up if appointment missed

= Media

Findings

= post data only and Marks’ meta-analysis estimate for linkage cannot apply as study participants were not newly diagnosed patients

= post data only and Marks’ meta-analysis estimates cannot apply as study participants were ex-offenders

= Pre and post statistic test was not reported and the study cannot be evaluated with any of 3 Tier criteria

= testing whether there was a different effect by deliverer (peer vs. professional) which was not comparing an intervention to a control or standard of care

As with the linkage to care findings, there were various interventions for all eight findings that showed health care utilization improvements. The intervention components found in almost all eight findings is case management that helped clients to navigate complex medical care systems and counseling and psychosocial support strategies. The most commonly used counseling and psychosocial support strategies were providing information or education [57, 59, 61, 63, 67] and identifying and addressing clients’ strengths [52, 55, 60]. The next most common intervention components were accompanying clients to medical appointments [55, 57, 59, 60] and helping with appointment coordination [52, 61].

The findings from three RCTs did not show any between-group differences on HIV care utilization outcomes. One RCT [68] tested an intensive case management model for ex-incarcerated persons. Two other RCTs [65, 69] that had HIV care utilization as one of multiple intervention goals (e.g., risk reduction, medication adherence, securing housing). Of the two RCTs, one provided limited case management services and ancillary services (i.e., immediate rental assistance) [69] while the other only trained participants on how to be a peer mentor [65]. None of the other intervention strategies were reported in these three non-significant findings.

There were two main differences between the interventions with significant evidence of HIV care utilization improvement and those without. The interventions with significant findings provided multiple strategies and also were specifically focused on improving linkage to care or HIV care utilization, while the interventions without significant evidence provided one or two intervention components and tended to have multiple intervention goals (such as risk reduction and medication adherence).

Among the seven findings that could not be evaluated with one of the three tiers, one was an RCT [64] that tested the differential intervention effect delivered by peer versus professionals for reducing gaps in care among newly diagnosed persons. The remaining six findings [21, 54, 56, 66, 70] reported the percentage of participants who had only one care visit at the post-intervention assessment and could not be evaluated with Marks et al’s retention in care finding (i.e., Tier III criterion). The intervention strategies found in these findings were similar to those findings that could be evaluated: case management, counseling and psychosocial support strategies, and appointment accompaniment. Four findings also used transportation as an intervention strategy.

Discussion

There is evidence from several studies conducted in the United States that interventions can improve linkage to HIV care and HIV care utilization outcomes. Interventions that focus specifically on linking or retaining patients in HIV care generally produce more favorable outcomes than interventions that are broad-based and try to address multiple prevention goals such as risk reduction and medication adherence (e.g., INSPIRE [65] and Housing and Health Study [69]). Our findings also suggest that a variety of interventions can be effective in producing positive outcomes: enhancing patients’ strengths through strengths-based counseling and helping navigate complex medical care systems may be especially beneficial in engaging and retaining HIV-diagnosed persons in HIV care. Also, reducing or removing barriers to accessing HIV care such as providing information and education about HIV care, accompanying clients to medical appointments and helping out with appointment coordination appear to be effective.

A few limitations of the literature and this review warrant comment. The evidence presented in this review is primarily based on well executed RCT and several non-RCT studies. Additionally, there is great diversity among the studies in target populations, study designs, intervention components, analysis approaches, and outcome measurements. The heterogeneity, coupled with a small number of rigorously designed studies (i.e., RCT) available in the current literature, makes comparisons across studies challenging and makes it impossible to unravel the independent effects or interactions among various intervention characteristics. Evidence shown in this review should be considered as promising and be further evaluated when more studies, especially controlled studies, become available.

While RCTs are often considered a gold standard for evidence, there are several challenges and barriers for conducting RCTs to evaluate linkage to care and HIV care utilization outcomes. Settings such as outreach centers may make it difficult to conduct randomization due to potential group contamination as well as ethical issues. In addition, not all studies have intervention-specific end-points, as health care utilization services provided by the sites may already exist, making it more challenging to conduct rigorous outcome evaluation. These challenges call for systematic outcome monitoring over time and study designs that are rigorous but feasible in real-world settings [33, 71].

The studies we reviewed focused on interventions at the individual level and not at the wider interpersonal, environmental or structural level. Less is known about strategies that can improve the provider-patient and family-patient relationships or address structural- or system-level barriers (e.g., flexible clinic hours, integrated appointment tracking systems, funding for HIV care). Access to HIV care involves a multi-dimensional process that includes individual, interpersonal and structural factors. The findings from this review mainly explored one piece of the puzzle: the individual-level interventions. More examination of the synergic effects of multi-dimensional interventions is needed to provide a more complete picture of best practices for linking and retaining HIV-diagnosed persons in care [72].

Although a large proportion of HIV-diagnosed persons in the studies we reviewed were part of hard-to-reach populations, several research gaps remain in terms of which interventions may work best for specific populations. The majority of studies were conducted in urban areas. Access to care in rural areas needs to be emphasized in future research, as barriers to service utilization are different between rural and urban areas [72]. In addition, barriers to care for newly diagnosed persons may be different from those who were diagnosed in the past but never linked to care or entered HIV primary care but dropped out. Our definition of “linkage to care” is broader than linking newly diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care as we also included linking previously diagnosed HIV-infected persons who never entered in care or persons who previously entered HIV primary care but have dropped out. More research is needed to closely examine intervention strategies or identify additional strategies that may work better with specific targeted populations.

Many studies included in this review did not clearly describe the care history of study participants, making it difficult to evaluate the intervention effect for specific target groups based on participants’ care history. Improving the reporting of participant characteristics (e.g., percentage of people who are newly or previously diagnosed) and care history (e.g., never in care, intermittent care) and using standardized measures of linkage and retention across studies will further facilitate our understanding of the processes of “being in care.”

In summary, more research is needed to examine the added effect of multi-dimensional interventions that not only address individual factors but also system and structural factors that are associated with barriers to linkage to care and HIV care utilization. Standardized measures should be established and transparent reporting of these measures should be considered in future studies to facilitate evaluating the effectiveness of the interventions. In conclusion, we identified several emerging individual-level intervention strategies for improving linkage to care and HIV care utilization. Incorporating these strategies when developing interventions may enhance the consistency and quality of health care for and the overall health of persons living with HIV.

Figure 1.

Study selection process

Appendix: Automated Search

Strategy Database: MEDLINE

Search Interface: OVID

Interface Key

| $ = truncation | |

| ab = abstract | ti = title |

| Subheadings | |

| /co = complications | /dt = drug therapy |

| /di = diagnosis sh | /nu = nursing |

| /pc = prevention and control | /px = psychology |

| /th = therapy | /tm = transmission |

HIV/HIV Positive Person MeSH and Keywords

-

1

HIV infections/co, dt, di, nu, pc, px, th, tm

-

2

HIV infect$.ti,ab

-

3

(HIV adj4 diagnos$).ti,ab

-

4

HIV positiv$.ti,ab

-

5

(HIV adj4 care).ti,ab

-

6

(HIV adj4 treatment$).ti,ab

-

7

living with HIV.ti,ab

-

8

or/1–7

Linking and Retention in Care MeSH and Keywords

-

9

(access$ adj4 care).ti,ab

-

10

(access$ adj4 barrier$).ti,ab

-

11

(access$ adj4 (treatment or service$)).ti,ab

-

12

(barrier$ adj4 care).ti,ab

-

13

case management.ti,ab

-

14

case manager$.ti,ab

-

15

(decreas$ adj4 barrier$).ti,ab

-

16

(engag$ adj4 (care or service$)).ti,ab

-

17

(enroll$ adj4 care).ti,ab

-

18

((enter$ or entry) adj4 care).ti,ab

-

19

((enter$ or entry) adj4 service$).ti,ab

-

20

(improv$ adj4 access$).ti,ab

-

21

(improv$ adj4 retention).ti,ab

-

22

((kept or keep$ or return$) adj4 appointment$).ti,ab

-

23

(link$ adj4 (retain$ or retent$)).ti,ab

-

24

(link$ adj4 care).ti,ab

-

25

(link$ adj4 case).ti,ab

-

26

(link$ adj4 treatment).ti,ab

-

27

(link$ adj4 service$).ti,ab

-

28

(outreach adj4 (care or link$ or program$)).ti,ab

-

29

((provision or provid$) adj4 (care or service$)).ti,ab

-

30

(reduc$ adj4 barrier$).ti,ab

-

31

((re engag$ or reengag$) adj4 (care or treatment or service$)).ti,ab

-

32

((re enter$ or reenter$) adj4 (care or treatment or service$)).ti,ab

-

33

((refer or refers or referred or referral$) adj4 (care or medical or treatment or clinic or service$)).ti,ab

-

34

((retain$ or retent$) adj4 care).ti,ab

-

35

(seek$ adj4 (care or treatment$)).ti,ab

-

36

(utiliz$ adj4 (treatment or care or service$)).ti,ab

-

37

(medical adj4 (care or treatment or service$)).ti,ab

-

38

(gap$ adj2 care).ti,ab

-

39

(visit adj2 (constan$ or consist$)).ti,ab

-

40

(appointment$ adj2 adher$).ti,ab

-

41

((follow-up or follow up) adj2 discontin$).ti,ab

-

42

((miss$ or schedul$) adj2 (visit$ or appointment$)).ti,ab

-

43

($contin$ adj2 care).ti,ab

-

44

or/9–43

-

45

8 and 44

-

46

Year limits (1996 +), Publication Type Limits: Clinical Trial, Controlled Clinical Trial, Corrected and Republished Article, Evaluation Studies, Journal Article, Meta-Analysis, Multicenter Study, Published Erratum, Randomized Controlled Trial, Retraction of Publication, Review, Review Literature, Technical Report, Validation Studies

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(1):41–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington, DC: Office of National AIDS Policy; [Accessed January 10, 2013]. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bani-Sadr F, Bedossa P, Rosenthal E, et al. Does early antiretroviral treatment prevent liver fibrosis in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):234–236. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818ce821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park WB, Choe PG, Kim SH, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: a predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007;261(3):268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherer R, Stieglitz K, Narra J, et al. HIV multidisciplinary teams work: support services improve access to and retention in HIV primary care. AIDS Care. 2002;14(Suppl 1):S31–S44. doi: 10.1080/09540120220149975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham WE, Hays RD, Ettl MK, et al. The prospective effect of access to medical care on health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with symptomatic HIV disease. Med Care. 1998;36(3):295–306. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):532–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks G, Gardner L, Craw JA, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons in the United States: a meta-ananlysis. AIDS. 2010;24(17):2665–2678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care: do more than 19% of HIV-infected persons in the US have undetectable viral load? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1168–1169. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CDC. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment--United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(47):1618–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beer L, Fagan JL, Valverde E, Bertolli J. Health-related beliefs and decisions about accessing HIV medical care among HIV-infected persons who are not receiving care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(9):785–792. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beer L, Heffelfinger J, Frazier E, et al. Use of and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in a Large U.S. Sample of HIV-infected Adults in Care, 2007–2008. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:213–223. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konkle-Parker DJ, Amico KR, Henderson HM. Barriers and facilitators to engagement in HIV clinical care in the Deep South: results from semi-structured patient interviews. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(2):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(Suppl 6):101–115. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith MY, Rapkin BD, Winkel G, Springer C, Chhabra R, Feldman IS. Housing status and health care service utilization among low-income persons with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(10):731–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen M, Hockman E, Smereck G, et al. Retaining women in HIV medical care. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(3):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakken T. Constitutional and social equality: legacies and limits of law, politics and culture. Indian J Gend Stud. 2000;7(1):71–82. doi: 10.1177/097152150000700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, Davis C, Cunningham WE. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(8):584–592. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, et al. Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: Results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(4):529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b56404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckerman A, Fontana L. Medical treatment for men who have sex with men and are living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Mens Health. 2008;3(4):319–329. doi: 10.1177/1557988308323902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalichman SC, Graham J, Luke W, Austin J. Perceptions of health care among persons living with HIV/AIDS who are not receiving antiretroviral medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16(5):233–240. doi: 10.1089/10872910252972285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Korin L, Gao W, Anastos K. HIV status, trust in health care providers, and distrust in the health care system among Bronx women. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):226–234. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein RB, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Johnson MO, et al. Insurance coverage, usual source of care, and receipt of clinically indicated care for comorbid conditions among adults living with human immunodeficiency virus. Med Care. 2005;43(4):401–410. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156850.86917.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner BJ, Cunningham WE, Duan N, et al. Delayed medical care after diagnosis in a US national probability sample of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2614–2622. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catz SL, McClure JB, Jones GN, Brantley PJ. Predictors of outpatient medical appointment attendance among persons with HIV. AIDS Care. 1999;11(3):361–373. doi: 10.1080/09540129947983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein MD, Crystal S, Cunningham WE, et al. Delays in seeking HIV care due to competing caregiver responsibilities. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(7):1138–1140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobias CR, Cunningham W, Cabral HD, et al. Living with HIV but without medical care: barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(6):426–434. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLuca JB, Mullins MM, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Kay L, Thadiparthi S. Developing a comprehensive search strategy for evidence-based systematic review. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2008;3(1):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.EBSCOhost-CINAHL [database online] Ipswich, Massachusetts: EBSCOhost; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.OVID-EMBASE [database online] New York, NY: Wolters, Kluwer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.OVID-MEDLINE [database online] New York, NY: Wolters Kluwer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.OVID-PsycINFO [database online] New York, NY: Wolters Kluwer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris SK, Samples CL, Keenan PM, et al. Outreach, mental health, and case management services: can they help to retain HIV-positive and at-risk youth and young adults in care? Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(4):205–218. doi: 10.1023/a:1027386800567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehrman SE, Gentry D, Yurchak BB, Freedman J. Outcomes of HIV/AIDS case management in New York. AIDS Care. 2001;13(4):481–492. doi: 10.1080/09540120120058012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Remafedi G. Linking HIV-seropositive youth with health care: evaluation of an intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15(3):147–151. doi: 10.1089/108729101750123625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barash ET, Hanson DL, Buskin SE, Teshale E. HIV-infected injection drug users: health care utilization and morbidity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(3):675–686. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Wong MD, et al. Utilization of health care services in hard-to-reach marginalized HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(3):177–186. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunningham CO, Sanchez JP, Li X, Heller D, Sohler NL. Medical and support service utilization in a medical program targeting marginalized HIV-infected individuals. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):981–990. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, et al. Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youths living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Lee M, Lightfoot M. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people: telephone and in-person delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S68–S77. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140604.57478.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimbrough LW, Fisher HE, Jones KT, Johnson W, Thadiparthi S, Dooley S. Accessing social networks with high rates of undiagnosed HIV infection: the social networks demonstration project. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1093–1099. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers JJ, Modica C, Dufour MS, Bernstein C, McNamara K. Routine rapid HIV screening in six community health centers serving populations at risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1269–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sattin RW, Wilde JA, Freeman AE, Miller KM, Dias JK. Rapid HIV testing in a southeastern emergency department serving a semiurban-semirural adolescent and adult population. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S60–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hruschka DJ, Schwartz D, John DC, Picone-Decaro E, Jenkins RA, Carey JW. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods. 2004;16(3):307–331. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hightow-Weidman LB, Jones K, Wohl AR, et al. Early linkage and retention in care: findings from the outreach, linkage, and retention in care initiative among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S31–S38. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajabiun S, Cabral H, Tobias C, Relf M. Program design and evaluation strategies for the Special Projects of National Significance Outreach Initiative. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S9–S19. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andersen MD, Smereck GA, Hockman EM, Ross DJ, Ground KJ. Nurses decrease barriers to health care by "hyperlinking" multiple-diagnosed women living with HIV/AIDS into care. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1999;10(2):55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV System Navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S49–S58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin JJ, Kang E, Kim JH, Martinez J, Eckholdt H. Serving Asians and Pacific Islanders with HIV/AIDS: challenges and lessons learned. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):910–927. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coleman SM, Rajabiun S, Cabral HJ, Bradford JB, Tobias CR. Sexual risk behavior and behavior change among persons newly diagnosed with HIV: the impact of targeted outreach interventions among hard-to-reach populations. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(8):639–645. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, et al. Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(5):597–606. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enriquez M, Farnan R, Cheng AL, et al. Impact of a bilingual/bicultural care team on HIV-related health outcomes. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hightow-Weidman LB, Smith JC, Valera E, Matthews DD, Lyons P. Keeping them in "STYLE": finding, linking, and retaining young HIV-positive black and Latino men who have sex with men in care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(1):37–45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molitor F, Waltermeyer J, Mendoza M, et al. Locating and linking to medical care HIV-positive persons without a history of care: findings from the California Bridge Project. AIDS Care. 2006;18(5):456–459. doi: 10.1080/09540120500217397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naar-King S, Bradford J, Coleman S, Green-Jones M, Cabral H, Tobias C. Retention in care of persons newly diagnosed with HIV: outcomes of the Outreach Initiative. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S40–S48. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, Wright K, Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: a pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):868–873. doi: 10.1080/09540120802612824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Purcell DW, Latka MH, Metsch LR, et al. Results from a randomized controlled trial of a peer-mentoring intervention to reduce HIV transmission and increase access to care and adherence to HIV medications among HIV-seropositive injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(Suppl 2):S35–S47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rich JD, Holmes L, Salas C, et al. Successful linkage of medical care and community services for HIV-positive offenders being released from prison. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):279–289. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wohl AR, Garland WH, Wu J, et al. A youth-focused case management intervention to engage and retain young gay men of color in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2011;23(8):988–997. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, et al. Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):356–364. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zaller ND, Holmes L, Dyl AC, et al. Linkage to treatment and supportive services among HIV-positive ex-offenders in Project Bridge. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(2):522–531. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Monitoring HIV care in the United States: indicators and data systems. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; [Accessed January 10, 2013]. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Monitoring-HIV-Care-in-the-United-States/Report-Brief.aspx?page=2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: what can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008;16(5):156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]