Abstract

Aim: Antisperm antibodies (ASA) in males cause the autoimmune disease ‘immune infertility’. The present study intended to detect the presence of ASA and their incidence in men with unexplained infertility, as well as to evaluate the correlation between the presence of ASA and semen parameter alterations.

Methods: Blood and sperm assessment were collected to carry out a direct and indirect mixed antiglobulin reaction (MAR) test and semen analysis in infertile and fertile men from the University Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine, Sao Paulo State University, Sao Paulo.

Results: In the MAR test, 18.18% of infertile men were positive for ASA. In fertile men, no positivity was found. A significant correlation between the presence of ASA with an increased white blood cell count plus a decreased hypoosmotic swelling test result was observed.

Conclusions: The results indicate that ASA are involved in reduced fertility. It is not ASA detection per se that provides conclusive information about the occurrence of damage to fertility. The correlation between infertility and altered seminal parameters reinforce the ASA participation in this pathology. (Reprod Med Biol 2007; 6: 33–38)

Keywords: antisperm antibody, infertility, man, semen, seminal parameters

INTRODUCTION

ANTISPERM ANTIBODIES (ASA) research began in 1899, when it was initially reported that sperm could be antigenic if injected into a foreign species. 1 The next year, it was found that sperm were also antigenic when injected into the same species. 2 The first correlation between ASA and male infertility was reported in 1954 by Wilson, with the identification of ASA in partners of infertile men. 3 Proposed infertility mechanisms of ASA have involved virtually all components of sperm and egg interaction, from hampered sperm capacitation to altered sperm motility, to diminished sperm–oocyte binding and faulty zona pellucida penetration. Antisperm antibodies have also been implicated in decreasing sperm motility, cervical mucus penetration, sperm survival and blocking the initiation of embryo cleavage. 4 The most common male immunologic concern in infertility, however, is antisperm antibodies.

Controversial rates of ASA incidence in infertile couples range from 9% to 36% in the literature, dependent on the test format. 5 In men, it is assumed that the development of ASA is mainly as a consequence of trauma to the blood–testis barrier, epididymis or vas deferens. 6 It had also been described as being associated with inflammation, 7 cryptorchidism, 8 varicocele 9 and surgical intervention in the genital organs. Often ASA appears to be of idiopathic origin. 10 In addition, there is a high prevalence of these antibodies in men after vasectomy. 11 Certainly, ASA are detectable by a number of classical immunologic methods, but whether the presence of ASA has a detrimental effect on fertility continues to be the subject of debate. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 The confusion over the role of ASA in infertility, to some extent, reflects the inadequacies of the current diagnostic techniques. 17 Thus, the recent literature of immunologically characterized sperm proteins, as cognate antigens of naturally occurring ASA or of artificially produced antibodies, has been quoted with respect to different sperm functions. As a practical consequence of the research on ASA related sperm proteomics, those ASA that decrease male fertility by inhibiting sperm functions essential for fertilization have been identified. 18 , 19

On the basis of these considerations, the purpose of the present study was to detect the presence of antisperm antibodies and their incidence in a general way in men with unexplained infertility, as well as to evaluate the correlation between the presence of ASA and semen parameter alterations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

THE EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL for the present research agrees with the Ethical Committee for Human Research, adopted by Sao Paulo State University.

Subjects

In order to obtain the men utilized in the present study, groups of fertile and infertile couples were selected after a preliminary interview, in which questions about age, prior paternity, family, clinical history, surgical history, childhood, occupation, infectious antecedents, personal habits, medicine use and sexual history were analyzed. In addition, the female partners of selected men did not present hormonal dysfunctions, tuba obstruction and reproductive system infection. Thus, 34 fertile control men with children under 2 years‐of‐age and 55 men with unexplained infertility were selected.

Semen analysis

Every sample was obtained through masturbation after a 3‐day period of sexual abstinence. All procedures and interpretations used were in accordance with established World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. 20 The sperm morphology evaluation was made according to the Kruger strict criteria. 21 The specimens were deposited directly into a sterile recipient and kept at 37°C in a dry‐heat incubator, and observed until the liquefaction, when the macroscopic analysis began. The macroscopic analysis was composed of liquefaction and measurement of pH, volume, color, and viscosity. The microscopic analysis included total and per milliliter concentration of spermatozoa, motility, viability and morphology. White blood cell count was measured by the peroxidase technique and hypoosmotic swelling (HOS) test. For agglutination of spermatozoa, which is when the motile spermatozoa stick to each other head to head, midpiece to midpiece, tail to tail or mixed, for example midpiece to tail, were considered. The adherence of either immotile or motile spermatozoa to mucus threads, to cells other than spermatozoa or to debris was not considered agglutination and should not be recorded as such. 20

Determination of antisperm antibodies

For screening of ASA in semen (direct technical) or serum (indirect technical), the mixed antiglobulin reaction (MAR test) was used. 20 , 22 The MAR was carried out with IgG coated erythrocytes and specific antiserum. Blood group O Rh‐positive erythrocytes were coated with human IgG and, subsequently, mixed with washed, viable sperm. Antiserum specific to the immunoglobulin used to coat the erythrocytes was added, and sperm‐erythrocytes agglutination occured in the presence of ASA. A reading was carried out in triplicate. A percentage of ≥50% of motile spermatozoa involved in the mixed agglutinates was considered MAR positive. Further analyses were carried out with MAR ≥20% as the additional cut‐off point.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as absolute numbers with percentages in parentheses or as median with interquartile ranges. Mann–Whitney U‐test and unpaired t‐test were used to compare the two groups. An association test was carried out between the men that had positive ASA and the seminal parameters. 23 The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

THE MEDIAN AGE of infertile (29.6 years) and fertile (30.0 years) men wasn't significantly different (data not shown).

By macroscopic analysis of semen – pH, volume, liquefaction, color and viscosity – no significant difference was observed among the groups of fertile and infertile men (Table 1).

Table 1.

Semen macroscopic analyses in fertile and infertile men groups

| Parameters | Fertile (n = 34) | Infertile (n = 55) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (mL) | 3.2 (2.3–4.5) | 2.9 (1.9–4.4) | NS |

| pH | 7.5 (7.4–7.6) | 7.5 (7.2–7.5) | NS |

| Viscosity | Normal | Normal | NS |

| Liquefaction (min) | 35 (25–50) | 35 (26–45) | NS |

| Color | Gray opalescent | Gray opalescent | NS |

P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U‐test. Values are median, with interquartile ranges in parentheses.

NS, not significant.

Through the microscopic analysis of the semen, a significant decrease of total concentration, per mL concentration, motility, viability and HOS test of infertile men was verified. The concentration of white blood cells in semen was increased in infertile men (Table 2). However these values are within the normal range, according to WHO guidelines.

Table 2.

Semen microscopic analyses in fertile and infertile men groups

| Parameters | Fertile (n = 34) | Infertile (n = 55) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sperm count (×106) | 327.5 (115.0–482.0) | 202.0 (59.0–366.0) | < 0.05† |

| Sperm count per mL (×106) | 98.5 (55.0–153.0) | 51.0 (24.5–98.2) | < 0.01† |

| Motility (% A + B) | 72.5 (63.0–86.0) | 56.0 (42.2–68.0) | < 0.001† |

| Viability (% live) | 91.5 (86.0–95.0) | 86.0 (79.0–90.0) | < 0.001† |

| Morphology (% normal forms) | 13.5 (8.0–16.0) | 9.0 (6.7–11.2) | < 0.005† |

| Hypoosmotic test (% normal) | 84.5 (76.0–89.0) | 76.0 (70.2–82.0) | < 0.01† |

| White blood cells (×106) | 0.00 (0.00–0.20) | 0.60 (0.30–1.75) | < 0.0001† |

Values are median, with interquartile ranges in parentheses.

Statistically significant difference with use of the Mann–Whitney U‐test.

The MAR test showed an increased percentage of positive ASA in infertile men. Of the infertile men, it was observed that (18.18%) tested positive to ASA, whereas the same percentage were borderline (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antisperm anitbodies by direct and indirect mixed antiglobulin reaction test in infertile and fertile men

| MAR test (red blood cells) | Fertile | Infertile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAR test Direct | MAR test Indirect | MAR test Direct | MAR test Indirect | |

| Negative (≤20%) | 33 (97.06) | 33 (97.06) | 35 (63.64) | 38 (69.09) |

| Boderline (≥21%, ≤49%) | 1 (2.94) | 1 (2.94) | 10 (18.18) | 9 (16.36) |

| Positive (≥50%) | 0 | 0 | 10 (18.18) | 8 (14.55) |

| Total | n = 34 | n = 34 | n = 55 | n = 55 |

Values are absolute numbers, with percentages in parentheses.

MAR, mixed antiglobulin reaction.

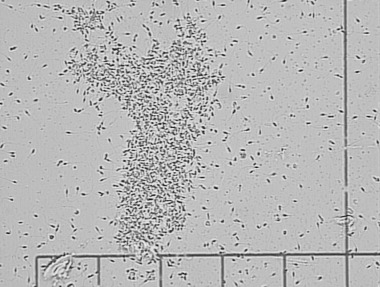

Despite no alteration between seminal parameters and the presence of ASA in fertile and infertile men, an increased white blood cells count plus a decreased HOS test were observed in the infertile men (Table 4). In addition, all infertile men with positive ASA had agglutinate spermatozoa in their semen (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Semen analyses in infertile men groups with negative and positive antisperm anitbodies

| Parameters | ASA negative (n = 35) | ASA positive (n = 10) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | 2.9 (2.61–3.90) | 2.5 (1.72–4.45) | NS |

| pH | 7.4 (7.31–7.46) | 7.5 (7.35–7.62) | NS |

| Viscosity | Normal | Normal | NS |

| Liquefaction | 35.0 (25.00–50.00) | 37.50 (20.00–60.00) | NS |

| Total sperm count (×106/mL) | 205.0 (147.10–254.60) | 254.5 (166.50–379.50) | NS |

| Sperm count per mL (×106/mL) | 40.0 (43.72–75.22) | 96.0 (86.75–200.25) | < 0.05† |

| Motility (% A + B) | 53.0 (43.47–60.41) | 67.5 (49.00–78.50) | NS |

| Morphology (% normal forms) | 9.0 (7.52–110.20) | 8.5 (7.75–10.50) | NS |

| Viability (% live) | 84.50 (81.12–88.03) | 89.5 (87.00–92.25) | NS |

| Hyposmotic test (% normal) | 82.0 (79.77–85.20) | 76.0 (65.25–82.75) | < 0.05† |

| White blood cells (×106) | 0.33 (0.32–0.71) | 1.3 (0.41–3.97) | < 0.001† |

Values are median with interquartile ranges in parentheses.

Statistically significant difference with use of the Mann–Whitney U‐test.

ASA, antisperm antibodies; NS, not significant.

Figure 1.

Spermatozoa agglutination in the ejaculate. All men that showed agglutinate spermatozoa in the semen presented ASA positive.

DISCUSSION

IN THE PRESENT study, we compared the spermatic parameters of fertile and infertile men. A decreased seminal quality was found in infertile men when compared with fertile men in several parameters. The literature shows that the incidence of infertility in newly married couples has increased in industrialized countries from 7% to 8% in the 1960s, whereas in the 1990s it was about 20% to 30%. Over the past few decades, the overall quality of semen has changed considerably worldwide. 23 , 24 One of the main reasons for this phenomenon might be the presence of toxic agents in the environment. 25 Work‐related activities frequently involve exposure to toxic chemicals, most of which are damaging to reproductive health and cause infertility in humans. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Occupational or accidental exposure to endocrine disrupters – chemical substances that interfere with synthesis, storage/release, transport, metabolism, binding, action or elimination of natural blood‐borne hormones responsible for the regulation of both homeostasis and developmental process – can lead to compromised fertility. 30 , 31

Morphological data depicted a high percentage of abnormal spermatozoa in groups of both infertile and fertile men, with a significant decrease in normal morphology in the infertile group. According to WHO guidelines, 20 the standard morphology determinants are 30% or more normal spermatozoa, analyzing unrefined as well as differentiated head, neck or tail anomalies. By using the Kruger criteria, 21 this is more rigorous, leading to the observation of spermatozoa with more tenuous abnormalities making the selection more refined and reliable, Because this classification scheme requires that all borderline forms be considered abnormal. An aspect that needs to be considered in infertility investigation and its treatment is the spermatozoa morphology. In this way, studies showed the importance of strict morphology in the in vitro fertilization prognoses. 21 , 32

In the present study, the presence of ASA, identified by MAR test, as the cause of infertility was 18.18% of infertile men. The corresponding female partners showed no positivity for ASA (data not shown). Thus, the presence of antisperm antibodies in the serum and seminal plasma could be responsible for the infertility. Many studies have tried to correlate the presence of ASA with various clinical situations in an attempt to delineate risk factors for the development of ASA. It is logical that conditions resulting in a breach of the blood–testis barrier would confer risk for ASA. However, the prevalence of ASA is unknown, as is the magnitude of their putative adverse fertility effects. This is not because of a lack of studies, but rather, the lack of a standardized, universally accepted method of testing for ASA. 33 The usual methods for detection of antisperm antibodies (immunobead assays [IBD] and MAR test) have the disadvantage of not identifying the specificity of the antibody. 33 In the context of disagreements in specific literature with regard to the test used in choosing the best treatment for patients with antisperm antibodies, the type of biological material researched (serum, semen and cervical mucus) and the titer are considered significant. 34 It can be inferred with certainty that there are specific antibodies that affect reproduction. In this manner, an effective diagnosis of antibody pathology might lead to less invasive treatments at a lower cost and shorter duration, in contrast to the utilization of the new methodologies of assisted reproduction, such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection. 33 , 35 , 36 Improved diagnosis and treatment of immunologic infertility, as well as a more complete understanding of the mechanism behind this phenomenon, are dependent on the identification and characterization of relevant sperm antigens. 37

Despite several semen parameters being believed to be affected by ASA, 33 consistent semen analysis abnormalities that can reliably identify infertile men who are at risk of harboring ASA have not been identified. 38

Rossato et al. 39 showed recently that the HOS test score in sperm samples from patients with autoimmune infertility was significantly lower than that observed in sperm from ASA negative normozoospermic subjects in the presence of normal and comparable sperm viability and motility. They also found that sperm with ASA bound to their plasma membranes showed low HOS test scores, and this non‐specific alteration of the plasma membrane integrity might participate in the determination of infertility caused by ASA.

In the present study, an increased proportion of motile spermatozoa that do not show progressive movement (‘shaking’) were found, but no statistical significance was associated with ASA. A significant correlation between the presence of ASA associated to increased white blood cells in semen, as well as a decreased HOS test was observed. All the men that showed agglutinate spermatozoa in their semen were also ASA test positive and, therefore, correlated directly between ASA presence and agglutination of spermatozoa. Thus, the presence of agglutination is suggestive of, but not sufficient evidence to prove the existence of, an immunological factor of fertility. 20 Sperm agglutination was also proposed as an indication for ASA testing of infertile men. 20 , 40

This emphasized the possibility that abnormalities of the semen analysis might predict the presence of ASA and could recommend an evaluation of ASA presence, a procedure that is not carried out as a routine evaluation during semen sample analysis in some laboratories. Nevertheless, we suggest that the antisperm antibodies detection test must be used independently whether seminal values are changed or not. Thus, the presence of antisperm antibodies in infertile men can be responsible for injury to the reproductive system, thus causing infertility.

When a semen sample shows a low HOS test score associated with increased white blood cells in semen and agglutination of spermatozoa, the presence of ASA can be assumed. These observations could also have important clinical implications in infertile men in order to save time and to direct the treatment to techniques of assisted reproduction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS WORK CONSTITUTED part of the MSc Thesis presented to Universidade Estadual Paulista‐UNESP, in 2005, by Patricia C. Garcia and was supported by a fellowship from CAPES.

REFERENCES

- 1. Landsteiner K. Zur Kenntnis der spezifisch auf blutkörperchen wirkende sera. Zentralbl Bakt 1899; 25: 546–549. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Metalnikoff S. Études sur la spermotoxine. Ann Inst Pasteur 1900; 14: 577–589. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilson L. Sperm agglutinins in human semen and blood. Endoc Gynecol Clin 1954: 652–655. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Mazumdar S, Levine AS. Antisperm antibodies: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Fertil Steril 1998; 70: 799–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins JA, Burrows EA, Yeo J, Younglai EV. Frequency and predictive value of antisperm antibodies among infertile couples. Hum Reprod 1993; 17: 592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gubin DA, Dmochowski R, Kutten WH. Multivariant analysis of men from infertile couples with and without antisperm antibodies. Am J Reprod Immunol 1998; 39: 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahmound AM, Tuyttens CL, Comhaire FH. Clinical and biological aspects of male immune infertility: a case‐controlled study of 86 cases. Andrology 1996; 28: 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinisi AA, Pasquali D, Papparella A et al. Antisperm antibodies in cryptorchidism before and after surgery. J Urol 1998; 160: 1834–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isitmangil G, Yildirim S, Orhan I, Kadioglu A, Akinci M. A comparison of the sperm mixed‐agglutination reaction test with the peroxidase‐labelled protein A test for detecting antisperm antibodies in infertile men with varicocele. B J U Int 1999; 84: 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lenzi A, Gandini L, Lombardo F, Rago R, Paoli D, Dondero F. Antisperm antibody detection: 2 clinical, biological, and statistical correlation between methods. Am J Reprod Immunol 1997; 38: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jarow JP, Sanzone JJ. Risk factors for male partner antisperm antibodies. J Urol 1992; 148: 1805–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bronson R. Antisperm antibodies: a critical evaluation and clinical guidelines. J Reprod Immunol 1999; 45: 159–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bronson R. Detection of antisperm antibodies: an argument against therapeutic nihilism. Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 1671–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Helmerhorst FM, Finken MJJ, Erwich JJ. Detection assays for antisperm antibodies: what do they test? Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 1669–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hjort T. Antisperm antibodies and infertility: an unsolvable question? Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 2423–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kutteh WH. Do antisperm antibodies bound to spermatozoa alter normal reproductive function? Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 2426–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Will WCC, Lawrence WC. Clinical associations and mechanism of action of antisperm antibodies. Fertil Steril 2004; 83: 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bohring C, Krause W. Immune infertility: towards a better understanding of sperm (auto)‐immunity. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bohring C, Krause W. The role of antisperm antibodies during fertilization and for immunological infertility. Chem Immunol Allergy 2005; 88: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Semen–Cervical Mucus Interaction, 4th edn Australia: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kruger TF, Menkveld R, Stander FSH. Sperm morphologic features as a prognostic factor in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 1986; 46: 1118–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coombs RRA, Rumke P, Edwards RG. Immunoglobulin classes reactive with spermatozoa in the serum and seminal plasma of vasectomized and infertile men In: Bratanov K, Vulchanov VD, Georgieva T, Somlev B, eds. Immunology of Reproduction. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy Sciences, 1973; 354. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zar JH. Biostatistician Analysis, 4th edn New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carlsen E, Giwercman A, Keiding N, Skakkeback NE. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during the past years. Br Med J 1992; 305: 609–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swan SH, Elkin EP, Fenster L. Have sperm densities declined? A reanalysis of global trend data. Environ Health Perspect 1997; 105: 1228–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Induslki JA, Sitarek K. Environmental factors which impair male fertility. Med Pr 1997; 48: 85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wyrobek AJ, Schrader SM, Perreault SD et al. Assessment of reproductive disorders and bird defects in communities near hazardous chemical sites. III. Guidelines for field studies of male reproductive disorders. Reprod Toxicol 1997; 11: 243–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Celis R, Feria‐Velasco A, Gonzalez‐Uzanga M, Torres‐Calleja J, Pedrón‐Nuevo N. Semen quality of workers occupationally exposed to hydrocarbons. Fertil Steril 2000; 73: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pereira OCM, Coneglian‐Marise MSP, Gerardin DCC. Effects of neonatal clomiphene citrate on fertility and sexual behavior in male rats. Comp Biochem Physiol 2003; 134: 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pereira OCM. Endocrine disruptors and hypothalamic sexual differentiation. Annu Rev Biomed Sci 2003; 5: 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kavlock RJ, Daston GP, DeRosa C et al. Research needs for the risk assessment of health and environmental effects on endocrine disruptors: a report of the US EPA‐sponsored workshop. Environ Health Perspect 1996; 104: 715–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biazotti MCS, Martinez EZ, Luiz FB et al. Influência das características do sêmen sobre os resultados de fertilização ‘in vitro’. J Bras Reprod Assist 2000; 4: 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hatasaka H. Immunologic factors in fertility. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2000; 43: 830–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barrat CLR, Dunphy BC, McLeod I, Cooke ID. The poor prognosis value of low to moderate levels of sperm surface‐bound antibodies. Hum Reprod 1992; 7: 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eggert‐Kruser W, Neuer A, Clussmann C et al. Seminal antibodies to human 60Kd heat shock protein (HSP 60) in male partners of subfertile couples. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shibahara H, Shiraishi Y, Suziki M. Diagnosis and treatment of immunologically infertile males with antisperm antibodies. Reprod Med Biol 2005; 4: 133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Diekman AB, Norton EJ, Westbrook A, Klotz KL, Naaby‐Hansen S, Herr JC. Anti‐sperm antibodies from infertile patients and their cognate sperm antigens: a review. Identify between SAGA‐1, the H6‐3C4 antigen, and CD52. Am J Reprod Immunol 2000; 43: 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cookson MS, Witt MA, Kimball KT, Grantmyre JE, Lipshultz LI. Can semen analysis predict the presence of antisperm antibodies in patients with primary infertility? World J Urol 1995; 13: 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rossato M, Galeazzi C, Ferigo M, Foresta C. Antisperm antibodies modify plasma membrane functional integrity and inhibit osmosensitive calcium influx in human sperm. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 1816–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Comhaire F, Vermeulen L. Human semen analysis. Hum Reprod 1995; 1: 343–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]