Abstract

Remodeling of maternal spiral arteries by invasion of extravillous trophoblast (EVT) is crucial for an adequate blood supply to the fetus. EVT cells that migrate through the decidual tissue destroy the arterial muscular lining from the outside (interstitial invasion), and those that migrate along the arterial lumen displace the endothelium from the inside (endovascular invasion). Numerous factors including cytokines/growth factors, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix‐degrading enzymes, and environmental oxygen have been proposed to stimulate or inhibit the differentiation/invasion of EVT. Nevertheless, it is still difficult to depict overall pictures of the mechanism controlling perivascular and endovascular invasion. Potential factors that direct interstitial trophoblast towards maternal spiral artery are relatively high oxygen tension in the spiral artery, maternal platelets, vascular smooth muscle cells, and Eph/ephrin system. On the other hand, very little is understood about endovascular invasion except for the involvement of endothelial apoptosis in this process. Only small numbers of molecules such as polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecules and CCR1 have been suggested as specific markers for the endovascular trophoblast. Therefore, an initial step to approach the mechanisms for endovascular invasion could be more detailed molecular characterization of the endovascular trophoblast.

Keywords: Endovascular trophoblast, Extravillous trophoblast, Interstitial trophoblast, Oxygen, Platelet

Introduction

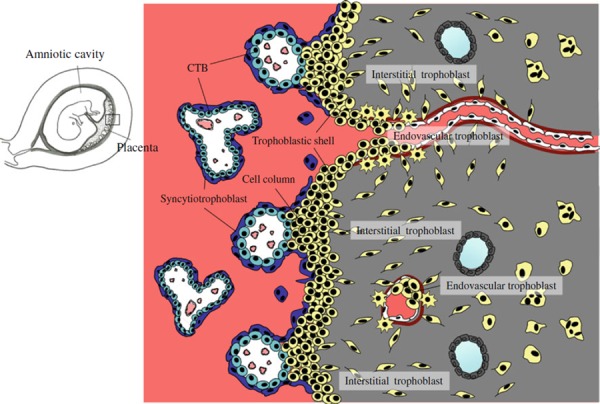

In human placenta, fetal‐derived trophoblast shows two distinct patterns of differentiation. In floating villi, cytotrophoblast (CTB) differentiates into syncytiotrophoblast and forms the syncytial layer, where the exchange of gas and nutrients takes place. On the other hand, at villus‐anchoring sites, CTB differentiates into extravillous trophoblast (EVT) and forms the stratified structure called cell column. In the cell column, EVT loses the proliferative activity and acquires the invasive capacity. Neighboring cell columns fuse with one another to create the trophoblastic shell that covers the surface of maternal tissue. The cell column and trophoblastic shell are composed of round‐shaped cells. From the end of the trophoblastic shell, a unipolar‐shaped interstitial trophoblast begins to migrate into the decidual tissue. The interstitial trophoblast appears to preferentially migrate towards and encircle the maternal spiral arteries [1]. These perivascular interstitial trophoblast cells disrupt the vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) layers and replace them with fibrinoid material. After embedding in the fibrinoid material, some of the perivascular trophoblast cells withdraw their dominant pseudopod and transform into a stellate shape [2].

The trophoblastic shell also gives rise to round‐shaped endovascular trophoblast. From the portion of the shell that lies over the distal opening of the spiral arteries, a cluster of the endovascular trophoblast cells flows into the arterial lumen [3]. Before 8 weeks of gestation, endovascular trophoblast forms a plug in the lumen spiral artery to block the maternal blood flow into the intervillous space [4]. This hypoxic milieu is considered to protect the early embryo against the deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species. After 8 weeks of gestation, the arterial plugs gradually dissolve and endovascular trophoblast begins to migrate along the arterial lumen in a retrograde manner, replacing the maternal endothelial cells (ECs). As a result, maternal arteries communicate with the intervillous space [4]. Enlargement of the feto‐maternal connection is gradual and uteroplacental circulation is not fully established until 12 weeks of gestation. No intervillous blood flow is detected by Doppler ultrasonography before 12 weeks of gestation [5], and the oxygen tension within the intervillous space rises from 18 mmHg (2.5%) at 8 weeks to 60 mmHg (8.5%) at 12 weeks of gestation [6]. Retrograde migration of endovascular trophoblast proceeds to the myometrial segment of the spiral artery after 14 weeks of gestation [1] (Fig. 1). Endovascular as well as interstitial trophoblast invasion, which is completed by 20–22 weeks of gestation, is limited to within the inner third of the myometrium. Interstitial trophoblast cells that do not reach the perivascular space cease migration and fuse with one another to form a multinucleated giant cell in the deep portion of the decidua or myometrium.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of early human placenta. In floating villus, cytotrophoblast (CTB) differentiates into multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast, where exchange of gas and nutrients takes place. At villus‐anchoring sites, CTB differentiates into extravillous trophoblast and forms the stratified structure called cell column. Extravillous trophoblast acquires invasive activity in the cell column. Neighboring cell columns fuse with one another to create the trophoblastic shell that covers the surface of maternal tissue. From the end of the cell column and trophoblastic shell, extravillous trophoblast begins to migrate through the decidual tissue (interstitial trophoblast) or along the lumen of spiral arteries in a retrograde manner (endovascular trophoblast)

Collectively, perivascular interstitial trophoblast destroys the VSMC layers and endovascular trophoblast replaces the ECs of the spiral arteries, transforming them from small resistant vessels to flaccid large‐caliber vessels that are unresponsive to vasoconstrictive agents. This process is called maternal (placental) vascular remodeling or physiological change. Of note is that the veins are never transformed in this way. The maternal vascular remodeling, which normally extends from the decidua into the inner third of the myometrium, ensures adequate placental perfusion and contributes to the establishment of a successful pregnancy [7]. In fact, the maternal vascular remodeling is limited to superficial decidua in cases of intrauterine growth restriction and/or pre‐eclampsia [8]. Accumulating evidence suggests that circulating factors such as soluble fms‐like tyrosine kinase 1 and soluble endoglin that are released from ischemic placenta cause systemic endothelial dysfunction, leading to the development of pre‐eclampsia [9]. In this respect, insufficient uteroplacental perfusion resulting from defective maternal vascular remodeling is likely to be one of the primary etiologies of intrauterine growth restriction and pre‐eclampsia. Thus, clarifying the mechanism of maternal vascular remodeling should contribute to approaching the pathophysiology of these abnormal conditions.

A growing number of factors such as cytokine/growth factors, chemokines, and environmental oxygen tension have been reported to modulate differentiation and/or the migration process of EVT. Vascular infiltration by EVT, however, is a unique phenomenon in primate placenta [10]. Moreover, in most non‐human primates, maternal vascular remodeling is restricted to the decidua, which in humans has to be considered pathological. Lack of proper experimental animal models has hampered the analysis of vascular remodeling and its mechanism is still largely unknown. This paper overviews the reported regulators of EVT differentiation/invasion with a specific focus on their potential contribution to maternal vascular remodeling.

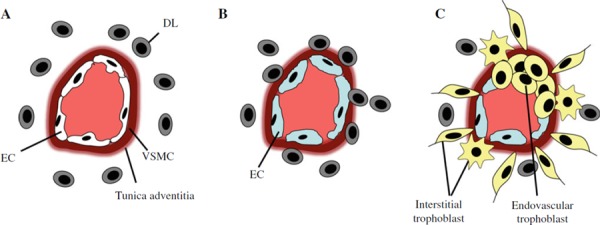

Histological features of maternal vascular remodeling (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Proposed events during maternal spiral artery remodeling. a Unremodeled artery. Decidual leukocytes (DLs) mainly composed of uterine natural killer cells and macrophages can be observed in the vicinity of the spiral artery. b Decidua‐associated (trophoblast‐independent) remodeling. Infiltration of DLs into arterial wall causes disruption and partial loss of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) layer along with endothelial cell (EC) swelling. This remodeling process occurs prior to the arrival of extravillous trophoblast. c Trophoblast‐dependent remodeling. Interstitial trophoblast destroys VSMC layer from outside the artery and endovascular trophoblast replaces ECs from the inside. Endovascular invasion only occurs in the arteries surrounded and remodeled by the interstitial trophoblast. Note that DL is absent from the arterial wall at this stage

In humans, unlike other species, decidualization of the endometrium evoked mainly by progesterone occurs independently of blastocyst presence in the uterine cavity and begins in the late secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. Decidua‐associated (trophoblast‐independent) vascular remodeling is characterized by disruption and partial loss of VSMC along with EC swelling and occurs prior to EVT arrival. A recent study indicates that uterine natural killer cells and macrophages infiltrating these vessels contribute to this remodeling [11].

After EVT begins to invade the uterine wall, trophoblast‐dependent vascular remodeling takes place. The trophoblast‐dependent remodeling is largely divided into two phases. The first phase is achieved by interstitial trophoblast that migrates towards the spiral arteries (i.e., perivascular interstitial trophoblast). Perivascular interstitial trophoblast destroys the VSMC layer and secretes fibrinoid material that is composed of fibronectin, collagen type IV, and laminin. As a result, perivascular interstitial trophoblast cells become embedded within this fibrinoid material, where some of them transform into stellate‐shaped trophoblast [2].

The second phase of the trophoblast‐dependent remodeling is characterized by the retrograde movement of endovascular trophoblast along the arterial lumen. Intriguingly, this endovascular migration only occurs in the arteries surrounded and remodeled by perivascular trophoblast [12], suggesting that the vascular remodeling by perivascular interstitial trophoblast (first phase) serves to pave the way for the subsequent endovascular trophoblast migration (second phase). The loss of ECs along with the presence of endovascular trophoblast in the arterial lumen could facilitate further disruption of the VSMC layers.

In vitro models for human EVT

Three in vitro models have mainly been utilized to examine the regulatory roles of various factors in the function of EVT. First, villous CTB cells purified from the first trimester of pregnancy acquire an invasive capacity when cultured on matrigel. These cells (referred to later as ‘invasive CTB’) are considered to mimic interstitial trophoblast [13]. Second, explants of the minced chorionic villi obtained from the first trimester of pregnancy, when cultured on appropriate extracellular matrix (ECM) such as matrigel or collagen I, can reproduce extravillous differentiation occurring at the villus‐anchoring site (referred to later as ‘villous explant culture’) [14, 15]. From the attached villous tips, an outgrowth of cell sheet and migration of unipolar cells, which resemble the cell column and the interstitial trophoblast in vivo, respectively, are observed. Thus, the villous explant culture could be an excellent model to examine the early step of extravillous differentiation (i.e., from CTB stem cells to cell column and subsequently to interstitial trophoblast). Third, EVT cells freshly isolated from this villous explant culture (referred to later as ‘isolated EVT’) as well as their immortalized counterpart (referred to later as ‘immortalized EVT’) are also available. These EVT cells are considered to be mainly composed of a unipolar interstitial trophoblast population and could be a suitable model to examine the migration process of interstitial trophoblast.

The preserved capacity of freshly isolated CTB stem cells cultured on matrigel to acquire an invasive property in vitro suggests that CTB stem cells have an intrinsic potential for extravillous differentiation that is triggered by the release from some differentiation‐inhibitory signal produced by the villous core and the interaction with appropriate ECM. In other words, other environmental factors are not essential for the initial step of extravillous differentiation occurring at villus‐anchoring sites, although they can negatively or positively influence this process. Interstitial trophoblast, however, further differentiates into perivascular stellate‐shaped trophoblast (perivascular differentiation) or multinucleated giant cells (multinucleated differentiation) during the migration through the maternal tissue. In addition, the cell column also gives rise to round‐shaped endovascular trophoblast (endovascular differentiation). Since these later differentiations cannot be simply reproduced in vitro, it is likely that certain environmental factors that are present at the differentiation sites (e.g., around or inside the spiral artery, deep portion of deciduas, or myometrium) are required for the respective differentiations.

Factors regulating EVT differentiation/invasion

Above‐mentioned in vitro models have revealed growing number of factors that regulate EVT invasion/differentiation process.

Cytokines/growth factors

Using invasive CTB cells or villous explant culture, epidermal growth factor (EGF) [16], interleukin (IL)‐1β [17], and activin [18] have been demonstrated to stimulate CTB differentiation towards EVT phenotype, whereas leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) [19] and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α [20] inhibit this process.

Insulin‐like growth factor (IGF)‐II secreted by EVT cells together with IGF binding protein (IGFBP)‐1 released from decidual tissue stimulates invasion of isolated EVT cells [21]. Endothelin (ET)‐1 released from blood vessels as well as from EVT cells also enhances invasion of immortalized EVT cells that express both ET(A) and ET(B) receptors [22]. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) released from the placental villous core has also been shown to promote invasion of immortalized EVT cells expressing HGF receptor (Met) [23, 24]. Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) are demonstrated to enhance invasion of invasive CTB cells that express both VEGFs and their receptors in an autocrine manner [25]. Heparin binding EGF promoted adhesion and outgrowth of mature blastocysts, indicating its invasion‐stimulatory effects on the trophoblast in the early stage of differentiation [26].

In contrast, IL‐10 reduces invasion of invasive CTB cells that express both IL‐10 and IL‐10 receptor [27]. Moreover, all three isoforms of transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β (TGF‐β1, TGF‐β2, TGF‐β3) that are primarily produced by decidual tissue have invasion‐inhibitory effects on isolated EVT cells as well as on EVT cells outgrown in villous explant culture [21, 28, 29]. Caniggia et al. [30] reported that TGF‐β3 expression in chorionic villi is inversely correlated with intervillous oxygen tension, i.e., increases during 7–8 weeks of gestation followed by marked down‐regulation by 9 weeks. Using villous explant culture, they also demonstrated that TGF‐β3 expression in chorionic villi is under the control of hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐1α and restrained CTB differentiation towards invasive phenotype under hypoxic condition is partly mediated by TGF‐β3 through HIF‐1α [30]. A later study by Lyall et al. [31], however, failed to reproduce the striking temporal changes in TGF‐β3 expression in the placenta.

Chemokines

Chemokines, a family of small chemotactic cytokines, can induce directional migration of the cells that possess the corresponding chemokine receptors towards the source of the chemokines. Several studies including ours have demonstrated expression of chemokine receptors in EVT [15, 32, 33]. Our reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction screening using isolated EVT cells showed dominant mRNA expression of three chemokine receptors, CCR1, CCR10 and XCR1 [15], while mRNAs for CCR3, CCR5, CCR7, CXCR4, CXCR6, and CX3CR1 have also been demonstrated in the later studies [32, 33]. Immunohistochemistry of early placental tissue confirmed the protein expression of CCR1, CCR3, CXCR4 and CX3CR1 on EVT [15, 33, 34]. Notably, protein expressions of CCR1 and CX3CR1 are localized from the cell column through the trophoblastic shell and endovascular trophoblast, but not on the interstitial trophoblast. In contrast, CCR3 protein is localized to the interstitial trophoblast. Invasive activity of isolated EVT or immortalized EVT cells is enhanced by chemokines that are ligands for CCR1, CCR3, and CX3CR1 [15, 33]. Although most chemokines are diffusely expressed in the maternal decidua and in the villous stroma, CCL21 (ligand for CCR7) and CXCL12 (ligand for CXCR4) are localized to blood vessels in the decidual tissue, CXCL10 (ligand for CXCR3) is expressed in the cluster of the decidual leukocytes that are associated with uterine glands, and peak expressions of CCL7 (ligand for CCR1, CCR2, and CCR3), CXCL6 (ligand for CXCR1 and CXCR2), CXCL14 (receptor is unknown), and CX3CL1 (ligand for CX3CR1) are expressed at sites of cell column initiation [32, 35].

Cell adhesion molecules

Cell adhesion molecules are localized on the cell surface and belong to distinct protein families: selectins, mucins, integrins, cadherins, and cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. During extravillous differentiation in the cell column, trophoblast down‐regulates cell adhesion molecules characteristic of stable epithelium such as integrin α6β4 and E‐cadherin, and subsequently up‐regulates those characteristic of endothelium/leukocytes such as integrin α1β1, integrin α4β1, integrin α5β1, integrin αVβ3, vascular endothelial cadherin, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)‐1, and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule‐1 [36, 37]. In vitro invasion assays using invasive CTB or isolated EVT cells and function‐perturbing antibodies have shown that many of these cell adhesion molecules are involved in the regulation of their migratory activity [21, 36, 37, 38]. The switching of these cell adhesion molecules can be reproduced on freshly isolated CTB stem cells cultured on matrigel. Moreover, it has been reported that some growth factors such as TGF‐β [21] and VEGFs [25], as well as surrounding oxygen tension [39], modulate the integrin expressions on EVT cells. Therefore, this switching is an intrinsically regulated process that accompanies extravillous differentiation and can be modulated by some environmental factors.

Oxygen tension

As mentioned above, during the first 10–11 weeks of gestation, the intervillous space contains relatively lower oxygen (~2.5% O2) than the maternal spiral artery (~20% O2). Although this low oxygen environment in the placenta is physiological and essential during the first trimester of pregnancy, it is pathological and associated with common pregnancy complication such as pre‐eclampsia in the second and third trimester. Using villous explant culture, Genbacev et al. [39] demonstrated that EVT cells outgrown from the explanted villous tips continue proliferating and fail to acquire invasive phenotype in a low oxygen environment (2% O2). Later studies using villous explant culture confirmed the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on EVT invasiveness [30, 40], while those using immortalized EVT cells yielded conflicting results [41, 42]. Thus, care should be taken before results obtained using immortalized EVT cells are extrapolated to EVT behavior in vivo [43].

The cellular responses to variation in the oxygen tension are considered to be mediated by HIFs. Expression of HIF proteins is high at 7–9 weeks of gestation when placental oxygen tension is low, and decreases when placental oxygen tension increases (after 10–12 weeks of gestation) [44].

ECM‐degrading enzymes

Invasion of EVT requires the degradation of ECM, which mainly owes to matrix metalloproteases (MMPs). MMPs are synthesized as proenzymes and processed to an active form by removal of the N‐terminal propeptide. Nearly 30 members of MMPs have been reported so far and can be divided into four groups according to their substrate specificity, i.e., collagenases (degrade collagen I, II, and III), gelatinases (degrade denatured collagens and native collagen IV), stromelysins (degrade fibronectin, laminin, collagen IV, V, elastin, and proteoglycans) and membrane‐type MMPs (activate MMP‐2). Among them, the gelatinases (MMP‐2 and MMP‐9) that mainly degrade collagen IV are the most studied MMPs in the placenta. During the first trimester, MMP‐2 is expressed in EVT cells, whereas MMP‐9 is mainly expressed in CTB cells [45]. The profile of gelatinase secretion from invasive CTB cells depends on the gestational age. MMP‐9 secretion is not detectable at 6 weeks of gestation, but gradually increases from 7 through 11 weeks of gestation. In contrast, MMP‐2 secretion is most prominent at 6 weeks of gestation and decreases from 7 through 11 weeks of gestation. Thus, MMP‐2 represents the main gelatinases secreted by EVT cells from 6 to 8 weeks of gestation, whereas MMP‐9 is dominant from 9 to 11 weeks [46].

MMPs are inhibited by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases (TIMPs; TIMP‐1, TIMP‐2, TIMP‐3, and TIMP‐4). Binding of TIMPs to the catalytic domains results in efficient inhibition of the enzymatic activity of MMPs. Co‐expression of MMPs and TIMPs has been shown in the isolated EVT cells [47].

Using invasive CTB cells, TNF‐α, IL‐1α, macrophage colony stimulating factor [48] and IL‐6 [49] as well as IGF‐I/IGF‐II/IGFBP‐1 system [50] have been shown to enhance MMP‐2 and/or MMP‐9 secretion, whereas IL‐10 [27] and TGF‐β [48] reduce MMP‐9 secretion. On the other hand, TGF‐β stimulates the synthesis of oncofetal fibronectin by invasive CTB cells [51]. EGF induces MMP‐9 and TIMP‐1 secretion from immortalized EVT cells [52]. LIF reduces gelatinolytic activity of freshly isolated CTB stem cells expressing integrin α6 (laminin receptor) [19]. Nitric oxide has been demonstrated to have a positive regulatory role on the activity of MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 in CTB cells purified from the term placentas [53].

Urokinase‐type plasminogen activator (uPA) and uPA receptor (uPAR) together with uPA inhibitors (PAI‐1 and PAI‐2) are considered to modulate EVT invasion. The interaction between EVT‐secreted uPA and EVT‐expressed uPAR leads to rapid activation of plasminogen to plasmin, which in turn promotes ECM degradation by activating certain MMPs as well as by its ability to directly degrade certain ECM components [54]. Indeed, EVT cells exhibit a highly polarized distribution of uPAR‐bound uPA at the migration front in vivo, supporting their essential role in EVT invasion [55].

Membrane‐bound cell surface peptidases

Membrane‐bound cell surface peptidases metabolize biologically active peptides by hydrolyzing peptide bonds at the extracellular site. Therefore, these peptidases can regulate the local concentration of biologically active peptides before they access their specific receptors on the cell surface. Based on the cleavage sites of substrate peptides, membrane‐bound peptidases are classified into three groups: aminopeptidase, carboxypeptidase, and endopeptidase. We found that two cell surface peptidases, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV (DPP‐IV) and carboxypeptidase‐M (CP‐M), are differentially expressed on specific subpopulations of EVT [56]. CP‐M is localized to invasive EVT (i.e., interstitial trophoblast and endovascular trophoblast), whereas DPP‐IV is expressed on non‐invasive EVT (i.e., EVT in the proximal part of the cell column and in the deep portion of the decidua and myometrium) [57, 58]. Furthermore, we found that a novel membrane‐bound cell surface peptidase, named laeverin, is specifically expressed on invasive EVT [59]. The enzymatic inhibition of these peptidases affected the invasive property of trophoblastic cells in vitro, suggesting that they degrade and inactivate invasion‐modulating substances at the cell surface. Indeed, a chemokine CCL5, one of the substrates for DPP‐IV, enhances invasion of isolated EVT cells that expresses its receptor, CCR1 [15]. Similarly, kisspeptin‐10, which was demonstrated to be one of the substrates for laeverin [60], inhibits invasion of isolated EVT cells [61].

Proposed mechanisms for placental vascular remodeling

With regard to placental vascular remodeling by EVT, there may be at least two questions to be addressed. (1) What directs interstitial trophoblast invasion preferentially towards maternal spiral artery (perivascular invasion)? (2) What regulates the retrograde invasion along arterial lumen and subsequent replacement of EC by endovascular trophoblast (endovascular invasion)? In this section, we discuss the potential mechanism for perivascular and endovascular trophoblast invasion based on the relevant literatures.

What directs interstitial trophoblast invasion preferentially towards maternal spiral artery?

It is intuitive to consider that some factor(s) derived from the maternal arterial wall or blood constituents directs the movement of interstitial trophoblast. Genbacev et al. [39] demonstrated that EVT cells outgrown from the explanted placental villous tips continue proliferating and fail to acquire invasive phenotype in a low oxygen environment (2% O2). From this finding, it is suggested that the relatively high oxygen tension in maternal arteries promotes trophoblastic differentiation toward an invasive phenotype, which could be one of the mechanisms that facilitates perivascular EVT invasion.

We propose maternal platelets as another candidate that facilitates perivascular EVT invasion [62]. Histological examination of the human placental bed revealed that maternal platelets are trapped by endovascular trophoblast aggregates that are formed inside the lumen of the spiral arteries. These platelets were attached to ECMs deposited around endovascular trophoblast and activated as demonstrated by the expression of P‐selectin, one of the activation markers for platelets [62]. In vitro, co‐culturing with platelets induced matrigel invasion of the isolated EVT cells. This invasion‐promoting effect does not require direct contact of platelets and the isolated EVT cells, suggesting that some soluble factors derived from the activated maternal platelets direct interstitial trophoblast invasion toward the spiral artery. Since a chemokine receptor CCR1 is expressed on isolated EVT cells [15], its ligand CCL5, that is known to be released from activated platelets, is one of the soluble factors that drive this invasion. In this theory, activation of platelets in the spiral arteries requires the pre‐existence of endovascular trophoblast aggregates. However, since perivascular trophoblast invasion is considered to precede the arrival of endovascular trophoblast [12], maternal platelet is not a primary initiator of perivascular trophoblast invasion but rather provides a positive feedback mechanism that promotes perivascular trophoblast infiltration.

Another candidate could be the Eph/ephrin system. Members of this system play a crucial role in tissue morphogenesis such as angiogenesis and axonal guidance [63]. Eph receptors as well as their ligands, ephrins, are classified into two subtypes, A and B. EphA receptors preferentially bind ephrinA ligands and EphB receptors bind ephrinB ligands. Upon cell–cell contact, the ligation of Eph receptors and their ephrin ligands generates bidirectional intracellular signals that lead to diverse biological readouts such as adhesion versus repulsion or increased versus decreased mortality depending on the cell types and context. At the villus‐anchoring site, trophoblastic expression of Eph/ephrin molecules switches from EphB4 on CTB stem cells to ephrinB1, ephrinB2, and EphB2 on interstitial trophoblast [64]. Similar to developing embryo proper [65], ephrinB2 and EphB4 are differentially expressed by ECs of uterine arteries and veins, respectively. Migratory activity of invasive CTB cells (expressing ephrinB1, ephrinB2 and EphB2) was inhibited by interaction with EphB4‐overexpressing 3T3 cells, whereas it was maintained after interaction with ephrinB2‐expressing 3T3 cells [64]. This could at least in part explain why interstitial trophoblast preferentially migrates toward the maternal artery (EphB4‐positive) and not toward the vein (ephrinB2‐positive).

Finally, using time‐lapse phase‐contrast microscopy, Hamzic et al. [66] observed that invasive CTB cells specifically target VSMCs in the co‐culture system. Although the precise mechanism for this targeting remains unknown, this could also partly explain why interstitial trophoblast preferentially targets maternal arteries that posses thicker VSMC layers than the veins. These systems, instead of being mutually exclusive, could be cooperatively operated with significant redundancy to ensure fulfillment of perivascular invasion that is an essential component of placental vascular remodeling.

What regulates the retrograde invasion along arterial lumen and subsequent replacement of ECs by endovascular trophoblast?

Deep arterial infiltration by EVT cells, including perivascular trophoblast and endovascular trophoblast, is a unique phenomenon to human placenta. Thus, analysis of endovascular invasion can only be achieved by using human samples. In general, observation of the endovascular trophoblast requires early‐pregnancy hysterectomy specimens. Difficulty in obtaining such specimens has hampered even molecular characterization of the endovascular trophoblast, although it is likely to be an imperative initial step to approach the mechanism of endovascular invasion. Only small numbers of specific molecular markers that can distinguish endovascular trophoblast from other EVT subpopulations such as interstitial trophoblast have been reported. Among them are blood group‐related antigen sialyl‐Lex [67], a polysialylated form of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM; CD56) [68], VEGF receptor‐3 (VEGFR‐3) [25], angiopoietin 2 [69], CCR1 [15], and CX3CR1 [33]. However, the functional significance of these molecules in endovascular invasion remains largely unknown.

Three in vitro and in vivo models have been devised to delineate the temporal events of perivascular and endovascular trophoblast invasion. In the first system, first‐trimester villous explants are cultured in contact with a small piece of decidua parietalis from the same patient [70]. In the second system, unmodified (non‐placental bed) spiral arteries are obtained from uterine biopsies at cesarean section and embedded in fibrin gels. Fluorescent‐labeled EVT cells (either isolated EVT or immortalized EVT cells) are seeded on top of the arterial segments to study interstitial invasion or perfused into the lumen of the arteries to study endovascular invasion [71]. In this model, a lower oxygen environment (3% O2) as well as TNF‐α inhibited both endovascular and interstitial invasion [72]. In addition, perfusion of the EVT cells or their conditioned medium into denuded spiral arteries induced apoptosis of the ECs and VSMCs. These apoptotic effects were mediated by the interaction of EVT‐secreted soluble Fas ligand with EC‐ or VSMC‐expressed Fas [73, 74] as well as the interaction of EVT‐expressed TNF‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (TRAIL) with VSMC‐expressed TRAIL receptors [75]. More interestingly, the attachment of the EVT cells to ECs was only observed for the spiral arteries obtained from pregnant myometrium, and not for those obtained from non‐pregnant myometrium or for the omental arteries taken at cesarean section [72], suggesting that the uterine spiral artery adopts a unique phenotype during pregnancy that admits entry of endovascular trophoblast. In the third system, first‐trimester chorionic villi are implanted into the mammary fat pads or under the kidney capsules of Scid mice [76]. Apoptosis of EC and VSMC but not of other cell types (e.g., stromal cells) was also confirmed in this system. Intriguingly, although a comparable number of EVT cells came into contact with the murine veins and arteries, apoptosis of the ECs and VSMCs was only observed in the arteries. Studies from these models strongly suggest that apoptosis of ECs is essential for their replacement by endovascular trophoblast, although the underlying mechanism of retrograde movement of the endovascular trophoblast is totally unresolved.

Summary and future direction

Numerous factors including cytokines/growth factors, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, and ECM‐degrading enzymes as well as environmental oxygen have been proposed to stimulate or inhibit the EVT differentiation/invasion program. Nevertheless, it is still difficult to delineate overall pictures of the mechanism controlling perivascular and endovascular invasion. Potential factors that could direct perivascular invasion are relatively high oxygen tension in the spiral artery, maternal platelets, VSMC layers, and Eph/ephrin system. On the other hand, very little is understood about endovascular invasion except for the involvement of endothelial apoptosis in their replacement by endovascular trophoblast. Only small numbers of molecules such as sialyl‐Lex, polysialylated NCAM, CCR1, CX3CR1, VEGFR‐3 and angiopoietin 2 have been suggested as specific markers for endovascular trophoblast. Therefore, an initial step to approach the mechanisms for endovascular invasion could be more detailed molecular characterization of the endovascular trophoblast. We observed that co‐culture with maternal platelets for an extended period (~48 h) induces the morphological transformation of isolated EVT into round‐shaped endovascular trophoblast‐like cells [77]. These endovascular trophoblast‐like cells could help to discover novel specific markers for endovascular trophoblast and eventually lead to a better understanding of endovascular trophoblast invasion.

References

- 1. Pijnenborg R, Dixon G, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Trophoblastic invasion of human decidua from 8 to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Placenta, 1980, 1 (1) 3–19 10.1016/S0143‐4004(80)80012‐9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shih JC, Chien CL, Ho HN, Lee WC, Hsieh FJ. Stellate transformation of invasive trophoblast: a distinct phenotype of trophoblast that is involved in decidual vascular remodelling and controlled invasion during pregnancy. Hum Reprod, 2006, 21 (5) 1299–1304 10.1093/humrep/dei489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Enders AC, Lantz KC, Schlafke S. Preference of invasive cytotrophoblast for maternal vessels in early implantation in the macaque. Acta Anat (Basel), 1996, 155 (3) 145–162 10.1159/000147800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burton GJ, Jauniaux E, Watson AL. Maternal arterial connections to the placental intervillous space during the first trimester of human pregnancy: the Boyd collection revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1999, 181 (3) 718–724 10.1016/S0002‐9378(99)70518‐1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coppens M, Loquet P, Kollen M, Neubourg F, Buytaert P. Longitudinal evaluation of uteroplacental and umbilical blood flow changes in normal early pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 1996, 7 (2) 114–121 10.1046/j.1469‐0705.1996.07020114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E. Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 1992, 80 (2) 283–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramsey EM. The story of the spiral arteries. J Reprod Med, 1981, 26 (8) 393–399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khong TY, De WF, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre‐eclampsia and by small‐for‐gestational age infants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 1986, 93 (10) 1049–1059 10.1111/j.1471‐0528.1986.tb07830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karumanchi SA, Epstein FH. Placental ischemia and soluble fms‐like tyrosine kinase 1: cause or consequence of preeclampsia?. Kidney Int, 2007, 71 (10) 959–961 10.1038/sj.ki.5002281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank HG, Kaufmann P. Nonvillous parts and trophoblast invasion. In: Benirschke K, Kaufmann P, editors. New York: Springer; 2000. p. 171–272.

- 11. Smith SD, Dunk CE, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL. Evidence for immune cell involvement in decidual spiral arteriole remodeling in early human pregnancy. Am J Pathol, 2009, 174 (5) 1959–1971 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pijnenborg R, Bland JM, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Uteroplacental arterial changes related to interstitial trophoblast migration in early human pregnancy. Placenta, 1983, 4 (4) 397–413 10.1016/S0143‐4004(83)80043‐5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher SJ, Cui TY, Zhang L, Hartman L, Grahl K, Zhang GY, Tarpey J, Damsky CH. Adhesive and degradative properties of human placental cytotrophoblast cells in vitro. J Cell Biol, 1989, 109 (2) 891–902 10.1083/jcb.109.2.891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Genbacev O, Schubach SA, Miller RK. Villous culture of first trimester human placenta—model to study extravillous trophoblast (EVT) differentiation. Placenta, 1992, 13 (5) 439–461 10.1016/0143‐4004(92)90051‐T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sato Y, Higuchi T, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Fujiwara H, Fujii S. Trophoblasts acquire a chemokine receptor, CCR1, as they differentiate towards invasive phenotype. Development, 2003, 130 (22) 5519–5532 10.1242/dev.00729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Librach CL, Feigenbaum SL, Bass KE, Cui TY, Verastas N, Sadovsky Y, Quigley JP, French DL, Fisher SJ. Interleukin‐1 beta regulates human cytotrophoblast metalloproteinase activity and invasion in vitro. J Biol Chem, 1994, 269 (25) 17125–17131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bass KE, Morrish D, Roth I, Bhardwaj D, Taylor R, Zhou Y, Fisher SJ. Human cytotrophoblast invasion is up‐regulated by epidermal growth factor: evidence that paracrine factors modify this process. Dev Biol, 1994, 164 (2) 550–561 10.1006/dbio.1994.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caniggia I, Lye SJ, Cross JC. Activin is a local regulator of human cytotrophoblast cell differentiation. Endocrinology, 1997, 138 (9) 3976–3986 10.1210/en.138.9.3976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bischof P, Haenggeli L, Campana A. Effect of leukemia inhibitory factor on human cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway. Am J Reprod Immunol, 1995, 34 (4) 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bauer S, Pollheimer J, Hartmann J, Husslein P, Aplin JD, Knofler M. Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha inhibits trophoblast migration through elevation of plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 in first‐trimester villous explant cultures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2004, 89 (2) 812–822 10.1210/jc.2003‐031351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Irving JA, Lala PK. Functional role of cell surface integrins on human trophoblast cell migration: regulation by TGF‐beta, IGF‐II, and IGFBP‐1. Exp Cell Res, 1995, 217 (2) 419–427 10.1006/excr.1995.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chakraborty C, Barbin YP, Chakrabarti S, Chidiac P, Dixon SJ, Lala PK. Endothelin‐1 promotes migration and induces elevation of [Ca2+]i and phosphorylation of MAP kinase of a human extravillous trophoblast cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2003, 201 (1–2) 63–73 10.1016/S0303‐7207(02)00431‐8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kauma SW, Bae‐Jump V, Walsh SW. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates trophoblast invasion: a potential mechanism for abnormal placentation in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1999, 84 (11) 4092–4096 10.1210/jc.84.11.4092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cartwright JE, Holden DP, Whitley GS. Hepatocyte growth factor regulates human trophoblast motility and invasion: a role for nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol, 1999, 128 (1) 181–189 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K, Janatpour M, Perry J, Karpanen T, Alitalo K, Damsky C, Fisher SJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. Am J Pathol, 2002, 160 (4) 1405–1423 10.1016/S0002‐9440(10)62567‐9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martin KL, Barlow DH, Sargent IL. Heparin‐binding epidermal growth factor significantly improves human blastocyst development and hatching in serum‐free medium. Hum Reprod, 1998, 13 (6) 1645–1652 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roth I, Fisher SJ. IL‐10 is an autocrine inhibitor of human placental cytotrophoblast MMP‐9 production and invasion. Dev Biol, 1999, 205 (1) 194–204 10.1006/dbio.1998.9122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Graham CH, Lala PK. Mechanism of control of trophoblast invasion in situ. J Cell Physiol, 1991, 148 (2) 228–234 10.1002/jcp.1041480207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lash GE, Otun HA, Innes BA, Bulmer JN, Searle RF, Robson SC. Inhibition of trophoblast cell invasion by TGFB1, 2, and 3 is associated with a decrease in active proteases. Biol Reprod, 2005, 73 (2) 374–381 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M. Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFbeta(3). J Clin Invest, 2000, 105 (5) 577–587 10.1172/JCI8316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lyall F, Simpson H, Bulmer JN, Barber A, Robson SC. Transforming growth factor‐beta expression in human placenta and placental bed in third trimester normal pregnancy, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Am J Pathol, 2001, 159 (5) 1827–1838 10.1016/S0002‐9440(10)63029‐5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drake PM, Red‐Horse K, Fisher SJ. Reciprocal chemokine receptor and ligand expression in the human placenta: implications for cytotrophoblast differentiation. Dev Dyn, 2004, 229 (4) 877–885 10.1002/dvdy.10477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hannan NJ, Jones RL, White CA, Salamonsen LA. The chemokines, CX3CL1, CCL14, and CCL4, promote human trophoblast migration at the feto‐maternal interface. Biol Reprod, 2006, 74 (5) 896–904 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu X, Li DJ, Yuan MM, Zhu Y, Wang MY. The expression of CXCR4/CXCL12 in first‐trimester human trophoblast cells. Biol Reprod, 2004, 70 (6) 1877–1885 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Red‐Horse K, Drake PM, Gunn MD, Fisher SJ. Chemokine ligand and receptor expression in the pregnant uterus: reciprocal patterns in complementary cell subsets suggest functional roles. Am J Pathol, 2001, 159 (6) 2199–2213 10.1016/S0002‐9440(10)63071‐4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Damsky CH, Librach C, Lim KH, Fitzgerald ML, McMaster MT, Janatpour M, Zhou Y, Logan SK, Fisher SJ. Integrin switching regulates normal trophoblast invasion. Development, 1994, 120 (12) 3657–3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, Genbacev O, Dejana E, Wheelock M, Damsky CH. Human cytotrophoblasts adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate. A strategy for successful endovascular invasion?. J Clin Invest, 1997, 99 (9) 2139–2151 10.1172/JCI119387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zeng BX, Fujiwara H, Sato Y, Nishioka Y, Yamada S, Yoshioka S, Ueda M, Higuchi T, Fujii S. Integrin alpha5 is involved in fibronectin‐induced human extravillous trophoblast invasion. J Reprod Immunol, 2007, 73 (1) 1–10 10.1016/j.jri.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science, 1997, 277 (5332) 1669–1672 10.1126/science.277.5332.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lash GE, Otun HA, Innes BA, Bulmer JN, Searle RF, Robson SC. Low oxygen concentrations inhibit trophoblast cell invasion from early gestation placental explants via alterations in levels of the urokinase plasminogen activator system. Biol Reprod, 2006, 74 (2) 403–409 10.1095/biolreprod.105.047332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Graham CH, Fitzpatrick TE, McCrae KR. Hypoxia stimulates urokinase receptor expression through a heme protein‐dependent pathway. Blood, 1998, 91 (9) 3300–3307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kilburn BA, Wang J, Duniec‐Dmuchowski ZM, Leach RE, Romero R, Armant DR. Extracellular matrix composition and hypoxia regulate the expression of HLA‐G and integrins in a human trophoblast cell line. Biol Reprod, 2000, 62 (3) 739–747 10.1095/biolreprod62.3.739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lash GE, Hornbuckle J, Brunt A, Kirkley M, Searle RF, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Effect of low oxygen concentrations on trophoblast‐like cell line invasion. Placenta, 2007, 28 (5–6) 390–398 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ietta F, Wu Y, Winter J, Xu J, Wang J, Post M, Caniggia I. Dynamic HIF1A regulation during human placental development. Biol Reprod, 2006, 75 (1) 112–121 10.1095/biolreprod.106.051557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Isaka K, Usuda S, Ito H, Sagawa Y, Nakamura H, Nishi H, Suzuki Y, Li YF, Takayama M. Expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 in human trophoblasts. Placenta, 2003, 24 (1) 53–64 10.1053/plac.2002.0867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu P, Wang YL, Zhu SJ, Luo SY, Piao YS, Zhuang LZ. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase‐2, ‐9, and ‐14, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase‐1, and matrix proteins in human placenta during the first trimester. Biol Reprod, 2000, 62 (4) 988–994 10.1095/biolreprod62.4.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tarrade A, Goffin F, Munaut C, Lai‐Kuen R, Tricottet V, Foidart JM, Vidaud M, Frankenne F, Evain‐Brion D. Effect of matrigel on human extravillous trophoblasts differentiation: modulation of protease pattern gene expression. Biol Reprod, 2002, 67 (5) 1628–1637 10.1095/biolreprod.101.001925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Meisser A, Chardonnens D, Campana A, Bischof P. Effects of tumour necrosis factor‐alpha, interleukin‐1 alpha, macrophage colony stimulating factor and transforming growth factor beta on trophoblastic matrix metalloproteinases. Mol Hum Reprod, 1999, 5 (3) 252–260 10.1093/molehr/5.3.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Meisser A, Cameo P, Islami D, Campana A, Bischof P. Effects of interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) on cytotrophoblastic cells. Mol Hum Reprod, 1999, 5 (11) 1055–1058 10.1093/molehr/5.11.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hills FA, Elder MG, Chard T, Sullivan MH. Regulation of human villous trophoblast by insulin‐like growth factors and insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein‐1. J Endocrinol, 2004, 183 (3) 487–496 10.1677/joe.1.05867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Feinberg RF, Kliman HJ, Wang CL. Transforming growth factor‐beta stimulates trophoblast oncofetal fibronectin synthesis in vitro: implications for trophoblast implantation in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1994, 78 (5) 1241–1248 10.1210/jc.78.5.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Qiu Q, Yang M, Tsang BK, Gruslin A. EGF‐induced trophoblast secretion of MMP‐9 and TIMP‐1 involves activation of both PI3K and MAPK signalling pathways. Reproduction, 2004, 128 (3) 355–363 10.1530/rep.1.00234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Novaro V, Colman‐Lerner A, Ortega FV, Jawerbaum A, Paz D, Nostro F, Pustovrh C, Gimeno MF, Gonzalez E. Regulation of metalloproteinases by nitric oxide in human trophoblast cells in culture. Reprod Fertil Dev, 2001, 13 (5–6) 411–420 10.1071/RD01036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lala PK, Chakraborty C. Factors regulating trophoblast migration and invasiveness: possible derangements contributing to pre‐eclampsia and fetal injury. Placenta, 2003, 24 (6) 575–587 10.1016/S0143‐4004(03)00063‐8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Multhaupt HA, Mazar A, Cines DB, Warhol MJ, McCrae KR. Expression of urokinase receptors by human trophoblast. A histochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Lab Invest, 1994, 71 (3) 392–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fujiwara H, Higuchi T, Sato Y, Nishioka Y, Zeng BX, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Ueda M, Maeda M. Regulation of human extravillous trophoblast function by membrane‐bound peptidases. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2005, 1751 (1) 26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sato Y, Fujiwara H, Higuchi T, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Maeda M, Fujii S. Involvement of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in extravillous trophoblast invasion and differentiation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2002, 87 (9) 4287–4296 10.1210/jc.2002‐020038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nishioka Y, Higuchi T, Sato Y, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Fujiwara H, Fujii S. Human migrating extravillous trophoblasts express a cell surface peptidase, carboxypeptidase‐M. Mol Hum Reprod, 2003, 9 (12) 799–806 10.1093/molehr/gag092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fujiwara H, Higuchi T, Yamada S, Hirano T, Sato Y, Nishioka Y, Yoshioka S, Tatsumi K, Ueda M, Maeda M, Fujii S. Human extravillous trophoblasts express laeverin, a novel protein that belongs to membrane‐bound gluzincin metallopeptidases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004, 313 (4) 962–968 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Maruyama M, Hattori A, Goto Y, Ueda M, Maeda M, Fujiwara H, Tsujimoto M. Laeverin/aminopeptidase Q, a novel bestatin‐sensitive leucine aminopeptidase belonging to the M1 family of aminopeptidases. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282 (28) 20088–20096 10.1074/jbc.M702650200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bilban M, Ghaffari‐Tabrizi N, Hintermann E, Bauer S, Molzer S, Zoratti C, Malli R, Sharabi A, Hiden U, Graier W, Knofler M, Andreae F, Wagner O, Quaranta V, Desoye G. Kisspeptin‐10, a KiSS‐1/metastin‐derived decapeptide, is a physiological invasion inhibitor of primary human trophoblasts. J Cell Sci, 2004, 117 (Pt 8) 1319–1328 10.1242/jcs.00971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sato Y, Fujiwara H, Zeng BX, Higuchi T, Yoshioka S, Fujii S. Platelet‐derived soluble factors induce human extravillous trophoblast migration and differentiation: platelets are a possible regulator of trophoblast infiltration into maternal spiral arteries. Blood, 2005, 106 (2) 428–435 10.1182/blood‐2005‐02‐0491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pitulescu ME, Adams RH. Eph/ephrin molecules—a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev, 2010, 24 (22) 2480–2492 10.1101/gad.1973910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Red‐Horse K, Kapidzic M, Zhou Y, Feng KT, Singh H, Fisher SJ. EPHB4 regulates chemokine‐evoked trophoblast responses: a mechanism for incorporating the human placenta into the maternal circulation. Development, 2005, 132 (18) 4097–4106 10.1242/dev.01971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin‐B2 and its receptor Eph‐B4. Cell, 1998, 93 (5) 741–753 10.1016/S0092‐8674(00)81436‐1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hamzic E, Cartwright JE, Keogh RJ, Whitley GS, Greenhill D, Hoppe A. Live cell image analysis of cell–cell interactions reveals the specific targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells by fetal trophoblasts. Exp Cell Res, 2008, 314 (7) 1455–1464 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. King A, Loke YW. Differential expression of blood‐group‐related carbohydrate antigens by trophoblast subpopulations. Placenta, 1988, 9 (5) 513–521 10.1016/0143‐4004(88)90024‐0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Burrows TD, King A, Loke YW. Expression of adhesion molecules by endovascular trophoblast and decidual endothelial cells: implications for vascular invasion during implantation. Placenta, 1994, 15 (1) 21–33 10.1016/S0143‐4004(05)80233‐4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhou Y, Bellingard V, Feng KT, McMaster M, Fisher SJ. Human cytotrophoblasts promote endothelial survival and vascular remodeling through secretion of Ang2, PlGF, and VEGF‐C. Dev Biol, 2003, 263 (1) 114–125 10.1016/S0012‐1606(03)00449‐4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dunk C, Petkovic L, Baczyk D, Rossant J, Winterhager E, Lye S. A novel in vitro model of trophoblast‐mediated decidual blood vessel remodeling. Lab Invest, 2003, 83 (12) 1821–1828 10.1097/01.LAB.0000101730.69754.5A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cartwright JE, Wareing M. An in vitro model of trophoblast invasion of spiral arteries. Methods Mol Med, 2006, 122, 59–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Crocker IP, Wareing M, Ferris GR, Jones CJ, Cartwright JE, Baker PN, Aplin JD. The effect of vascular origin, oxygen, and tumour necrosis factor alpha on trophoblast invasion of maternal arteries in vitro. J Pathol, 2005, 206 (4) 476–485 10.1002/path.1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ashton SV, Whitley GS, Dash PR, Wareing M, Crocker IP, Baker PN, Cartwright JE. Uterine spiral artery remodeling involves endothelial apoptosis induced by extravillous trophoblasts through Fas/FasL interactions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2005, 25 (1) 102–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Harris LK, Keogh RJ, Wareing M, Baker PN, Cartwright JE, Aplin JD, Whitley GS. Invasive trophoblasts stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis by a fas ligand‐dependent mechanism. Am J Pathol, 2006, 169 (5) 1863–1874 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Keogh RJ, Harris LK, Freeman A, Baker PN, Aplin JD, Whitley GS, Cartwright JE. Fetal‐derived trophoblast use the apoptotic cytokine tumor necrosis factor‐alpha‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand to induce smooth muscle cell death. Circ Res, 2007, 100 (6) 834–841 10.1161/01.RES.0000261352.81736.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Red‐Horse K, Rivera J, Schanz A, Zhou Y, Winn V, Kapidzic M, Maltepe E, Okazaki K, Kochman R, Vo KC, Giudice L, Erlebacher A, McCune JM, Stoddart CA, Fisher SJ. Cytotrophoblast induction of arterial apoptosis and lymphangiogenesis in an in vivo model of human placentation. J Clin Invest, 2006, 116 (10) 2643–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sato Y, Fujiwara H, Konishi I. Role of platelets in placentation. Med Mol Morphol, 2010, 43 (3) 129–133 10.1007/s00795‐010‐0508‐1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]