Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the clinical value of day 3 serum anti‐Müllerian hormone (AMH) compared with day 3 serum follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) day estradiol (E2) levels and antral follicle count (AFC) in the prediction of poor ovarian response in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH).

Methods

AMH, FSH and AFC on day 3 as well as hCG day E2 levels were determined in 164 subjects. Receiver operating curve analyses and area under curves (AUC) of the study parameters were performed. Predictive values of the levels of day 3 AMH, FSH, AFC, and hCG day E2 as clinical parameters of ovarian response to COH were studied.

Results

Thirty‐eight women were defined as poor responders. The day 3 AMH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC of normal responders were significantly higher than those of the poor responders. In predicting poor response, the AUC of day 3 AMH level was significantly higher than that of day 3 FSH level but was similar to the hCG day E2 level. Day 3 AMH, FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC were found to predict a poor response. Day 3 AMH and hCG day E2 levels were more predictive compared with day 3 FSH level and AFC. The cut‐off level of AMH was ≤2 with a sensitivity of 78.9% and a specificity of 73.8%.

Conclusion

Day 3 AMH has the ability to predict a poor response to COH and it is more predictive than day 3 FSH and AFC.

Keywords: Anti‐Müllerian hormone, Follicle‐stimulating hormone, Antral follicle count, In vitro fertilization, Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, Poor responders, Infertility

Introduction

In spite of many advances in assisted reproductive technology (ART), the prediction of ovarian response following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is still a considerable problem in clinical practice. The evaluation of ovarian reserve in women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) is useful in optimizing the treatment protocol and increasing the chance of pregnancy. Ovarian response can be considered abnormal when the COH provides less than six follicles at follicle puncture. With such a yield, the chance of obtaining a live birth through IVF is less than expected by the infertile couple [1].

A large number of clinical parameters have been shown to predict poor ovarian response to stimulation with exogenous gonadotropins and have been introduced into clinical practice. These include age, basal serum follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH) and inhibin B levels, antral follicle count (AFC), ovarian volume, a number of dynamic tests and, more recently, anti‐Müllerian hormone (AMH) [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

AMH is produced by the granulosa cells of primary and preantral follicles in the postnatal ovary and has two sites of action. It inhibits initial follicle recruitment and inhibits FSH‐dependent growth and the selection of preantral and small antral follicles. Detailed studies in rodents have shown that AMH expression starts in the columnar granulosa cells of primary follicles immediately after differentiation from the flattened pregranulosa cells of primordial follicles. Expression is highest in the granulosa cells of preantral and small antral follicles, and gradually diminishes in the subsequent stages of follicle development. AMH is no longer expressed during the FSH‐dependent final stages of follicle growth. AMH expression also disappears when follicles become atretic [11, 12].

AMH is a member of the transforming growth factor‐β family synthesized exclusively by the gonads of both sexes. Over the last decade, several studies have examined the clinical usefulness of serum AMH levels as a predictor of ovarian response and pregnancy in ART cycles. The availability of a reliable measure of ovarian reserve is essential during the management of infertile women. Currently, serum AMH level seems to be more strongly related to the ovarian reserve and to be a more discriminatory marker of ART outcome than FSH, inhibin B, or estradiol (E2), which are the more commonly used tests. Further studies are needed to determine AMH cut‐off values in subgroups of patients with several infertility causes [13].

The aim of this prospective study was to investigate the value of day 3 AMH compared with those of day 3 FSH and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) day E2 levels and AFC as predictors of ovarian response in a population of women undergoing a first cycle of COH with exogenous gonadotropins during IVF with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles.

Materials and methods

From February 2009 to March 2010, 164 women undergoing IVF with ICSI were included in this study at the Cerrahpasa IVF Center. An informed consent was obtained from all women and approval from the Human Ethics Committee of Istanbul University was obtained. Our inclusion criteria were: (1) age under 40 years old, (2) basal FSH level <15 mIU/mL, (3) presence of both ovaries, (4) no current or past diseases affecting ovaries or gonadotropin or sex steroid secretion, clearance, or excretion, (5) no evidence of ovarian cyst >2 cm in diameter, and (6) no polycystic ovaries. Poor response was defined as the retrieval of less than three oocytes.

All patients received gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist, leuprolide acetate (1 mg/day s.c., Lucrin, Cedex, France) beginning on the 21st day of the previous cycle. Leuprolide acetate was reduced to 50 μg/day and gonadotropin (Gonal F, Serono, Swiss or Puregon, Schering Plough, Istanbul) 150 IU for patients ≤30 years old and 225 IU for patients >30 years old was started daily i.m. A transvaginal ultrasound scan was arranged on days 7 and 9 of ovarian stimulation and every 1 or 2 days thereafter, as required. Whenever a follicle size >12 mm was seen, the E2 level was measured. The dose of the gonadotropin was changed according to the follicular growth. When more than 2 follicles were seen that were ≥17 mm, hCG (Pregnyl, 10000 IU, Schering Plough, Istanbul or Ovitrelle 250 mcg, Serono, Swiss) was injected to induce final oocyte maturation and 36 h later, ovum pick‐up was performed. The embryos were transferred after 3 days if fertilization had occurred. The luteal phase was supported with progesterone 200 mg administered by the vaginal route t.i.d. (Progynex® jel, Koçak, Istanbul, or Crinone gel® 8%, Merk Serono, Istanbul) or by 100 mg progesterone injection daily i.m. (Progynex® ampule, Koçak, Istanbul) until the day of the pregnancy test 12 days after the embryo transfer.

We recorded age, body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), AFC, and levels of AMH, FSH, and E2 on hCG day. On day 3 of a spontaneous menstrual cycle within 3 months of commencing ovarian stimulation, blood samples for assays of FSH and AMH were obtained by venepuncture at approximately 08:30 hours.

Measurements of AMH were determined in duplicate using the AMH/MIS enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kit (Diagnostic Systems Lab, Webster, TX, USA). The sensitivity of the assay was 0.017 ng/mL. The intra‐ and inter‐assay variations were <5% and <8%, respectively.

The FSH and E2 concentrations were estimated using the Immulite semi‐automated assay system. On the third day of menstrual cycles, a transvaginal ultrasound scan was performed to assess the total number of antral follicles measuring 2–5 mm in diameter and to confirm normal anatomy of the pelvic organs. E2 levels were evaluated on the day of hCG administration.

Statistical analyses

Data were presented as mean ± SD or number as appropriate. Comparison of age, BMI, day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels, AFC, number of developing follicles, stimulation days, and total gonadotropin dose was performed using the t test. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis with area under curve (AUC) (ROC AUC) were used to determine the predictive value of day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC for poor response to COH. Statistical significance was considered to be reached at p values of < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents selected clinical data of normal (n = 126) and poor (n = 38) responders. There was no significant difference between normal and poor responders with regard to BMI (25.1 ± 4.1 vs. 25.3 ± 4.1, p = 0.735). There was, however, a significant difference between poor and normal responders with regard to age (31.6 ± 4.7 vs. 33.9 ± 4.4, p = 0.01). The AMH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC of normal responders were significantly higher than those of poor responders (3.3 ± 2.0 vs. 1.5 ± 0.9, 1466.2 ± 988.4 vs. 576.3 ± 522.5, 7.9 ± 4.1 vs. 4.4 ± 2.6, respectively, p = 0.01). The FSH level of poor responders was significantly higher than that of normal responders (9.1 ± 5.6 vs. 6.2 ± 2.0, p = 0.01).

Table 1.

Selected clinical data of poor and normal responders undergoing IVF with ICSI cycles

| Normal responders (n = 126) | Poor responders (n = 38) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.6 ± 4.7 | 33.9 ± 4.4 | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 4.1 | 25.3 ± 4.1 | 0.735 |

| AMH (ngr/mL) | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.01 |

| FSH day 3 (mIU/mL) | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 9.1 ± 5.6 | 0.01 |

| hCG day E2 (pg/mL) | 1466.2 ± 988.4 | 576.3 ± 522.5 | 0.01 |

| AFC (n) | 7.9 ± 4.1 | 4.4 ± 2.6 | 0.01 |

| No. of developing follicles | 14.5 ± 7.1 | 4.0 ± 2.6 | 0.001 |

| Stimulation days | 9.6 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 2.9 | 0.119 |

| Total gonadotropin dose (IU) | 2338.6 ± 1211.0 | 3374.3 ± 1650.3 | 0.001 |

BMI body mass index (kg/m2), AMH anti‐Müllerian hormone, FSH follicle stimulating hormone, E2 estradiol, AFC antral follicle count

The number of developing follicles of normal responders was significantly higher than that of poor responders (14.5 ± 7.1 vs. 4.0 ± 2.6, p = 0.01). Stimulation days of poor responders were longer than normal responders but did not reached statistical significance (9.6 ± 1.7 vs. 10.2 ± 2.9, p = 0.119). The total gonadotropin dose was higher in poor responders compared to normal responders (2338.6 ± 1211.0 vs. 3374.3 ± 1650.3, p = 0.01).

Table 2 shows the AUC values for day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC of the study population to predict poor responders. Day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC were significant for the prediction of poor response. The AMH level provided an AUC of 0.818 for poor response, indicating a useful potential for predicting poor stimulation response.

Table 2.

Potential of day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC to predict poor responders

| Poor responders (n = 38) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | 95% CI | Significance | Cut‐off | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 0.818 | 0.745–0.891 | 0.01 | ≤2 | 78.9 | 73.8 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 0.668 | 0.562–0.773 | 0.01 | >6.7 | 60.5 | 69.0 |

| hCG day E2 (pg/mL) | 0.860 | 0.775–0.946 | 0.01 | ≤791 | 88.0 | 78.3 |

| AFC (n) | 0.760 | 0.678–0.842 | 0.01 | ≤6 | 80.6 | 56.6 |

AMH anti‐Müllerian hormone, FSH follicle stimulating hormone, E2 estradiol, AFC antral follicle count, CI confidence interval, ROC AUC receiver operating curve analysis area under curve

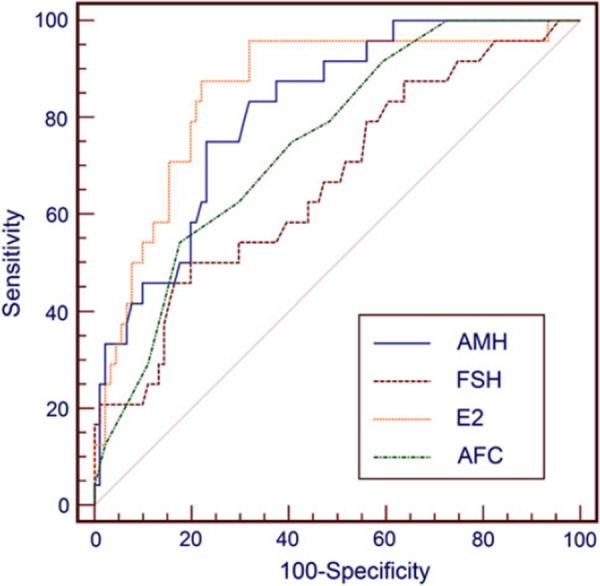

Figure 1 displays the comparison of ROC AUC of day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC for the prediction of poor response. In predicting poor response, the AUC of the AMH level was significantly higher than that of the FSH level (p = 0.048). The AUC of the AMH level was similar to those of the hCG day E2 level and the AFC (p = 0.425, p = 0.257, respectively). The AUC of the FSH level was significantly lower than that of the hCG day E2 level (0.01). The AUC of the FSH level and the AFC was similar (p = 0.261). The AUC of the hCG day E2 level was significantly higher than that of the AFC (p = 0.04).

Figure 1.

Comparison of AUC of day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC for prediction of poor response

Discussion

Day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC were significant for predicting poor response. The day 3 AMH and hCG day E2 levels were more predictive with comparable AUC (0.818 and 0.860, respectively) compared with the similar AUC of day 3 FSH level and AFC (0.668 and 0.760, respectively). The cut‐off level of AMH was ≤2 with a sensitivity of 78.9% and a specificity of 73.8% for the prediction of poor response. There is no study investigating the role of day 3 AMH and FSH and hCG day E2 levels and AFC in the prediction of poor response to COH in IVF/ICSI cycles in the same settings.

Because of no consensus on the definition of poor response for women, a large proportion of women (2–30%) were reported as poor responders [14]. For defining poor response, there are two important criteria: the numbers of developed follicles and the numbers of retrieved oocytes. The proposed numbers for these criteria varies according to different studies and the cut‐offs used were from <3 to <5 for dominant follicles on hCG day, and from <3 to <5 for retrieved oocytes [15]. If the cycle is cancelled due to no acceptable ovarian response to COH, it is logical to define it as poor response. Whatever criterion is considered, the pregnancy rate of poor responders was definitely lower compared with that of normal responders in age‐matched settings [16, 17, 18].

In the clinical practice of IVF, it may be useful to correctly predict the occurrence of poor response for determining an appropriately planned treatment and avoiding an unsuccessful COH, thus contributing to a decrease in the number of cancelled cycles, the cost of IVF management and the psychological stress of cycle cancellation for the couple. Finally improved counseling for the couple about the possibility of poor response may ameliorate disappointment and distress.

van Disseldorp et al. [19] compared the AFC with the AMH as to both their inter‐cycle variability across four subsequent cycles and their stability across a full cycle in 77 women undergoing intrauterine insemination. They demonstrated that AMH provided less intra‐individual fluctuation than the AFC both within and between cycles. They concluded that the findings suggested AMH to be a better cycle‐independent parameter to assess ovarian reserve, but that future prospective studies specifically designed for this purpose were needed to confirm the hypothesis. If the AFC is used for screening ovarian reserve, it is recommended to count follicles in the size range 2–10 mm, in view of better cycle stability.

Jayaprakasan et al. [20] evaluated three‐dimensional ultrasound parameters, AFC, ovarian volume, and ovarian vascularity indices with AMH and other conventional endocrine markers for the prediction of poor response to COH. They concluded that pretreatment AFC and AMH are the most significant predictors of the number of oocytes retrieved and of poor ovarian response to COH, although none of the markers studied, including AFC and AMH, were significant predictors of non‐conception to warrant the modification of treatment.

Singer et al. [21] investigated the FSH/AMH correlation in a selected population of women with poor ovarian reserve who were undergoing fertility treatment. They demonstrated a statistical association between FSH and AMH in assessing ovarian reserve. They suggested that using FSH and AMH in combination may improve the evaluation of ovarian reserve; however, it remained to be determined which of these two ovarian function parameters is superior in assessing ovarian reserve with a single test and which test, or combination of tests, could be used in the future in routine infertility evaluations.

Gnoth et al. [22] conducted a larger prospective trial calculating the cut‐off level of AMH and evaluating the relevance of its measurement for determining treatment strategies and predicting their outcome in a routine IVF program with 316 women entering their first IVF/ICSI cycle. They suggested that AMH was a predictor of ovarian response and suitable for screening with levels ≤1.26 ng/mL that was highly predictive of reduced ovarian reserve but that prediction should be confirmed by a second line AFC.

Nardo et al. [23] investigated the relationship between AMH and AFC, and to determine whether these markers of ovarian reserve correlate with chronological age and other clinical parameters. They found that serum AMH levels and AFC correlated with each other and declined in accordance with age. There were only weak, non‐significant correlations with lifestyle factors and reproductive history. They suggested that those markers could be used individually or together to assess the age‐related decline of ovarian function in normo‐ovulatory IVF patients.

Fréour et al. [12] evaluated serum AMH level with FSH, inhibin B, or E2 to assess ovarian reserve in 69 women undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles for optimization of the treatment protocol. They showed that AMH was significantly correlated with the number of eggs collected and may be used as a negative predictive value for the success of IVF management but there was a need for the determination of AMH cut‐off values.

One of the main advantages of basal AMH measurement compared to other hormonal markers of ovarian reserve is the possibility of being used as a menstrual cycle independent marker since AMH provides a stable level with very low inter‐ and intra‐cycle variability. Clinicians may have a reliable serum marker of ovarian response that can be measured independently of the day of the menstrual cycle [24]. The variable clinical performance of AMH tests has been demonstrated by several studies because of the use of different variants of AMH assay by IVF units [25, 26]. Two different kits have been developed for AMH measurement (Immunotech–Beckman Coulter and Diagnostic System Laboratories). The main difference between the two assays is in the antibodies which have been obtained by using different standard proteins, thus leading to differences in the assay sensitivities. Initial studies comparing the two assays have shown that AMH levels appear to be 4‐ to 5‐fold lower with the DSL assay compared with the Immunotech–Beckman assay [27]. There is a need for a well‐calibrated AMH test before it can be used routinely in women requiring evaluation of ovarian response before COH. Although AMH is presented as a good marker in the prediction of ovarian response to COH, AMH is not a good predictor for the occurrence of pregnancy after ART treatment. Therefore, routine screening for a poor ovarian reserve status using AMH is not to be recommended. However, ovarian response prediction using AMH may open ways for patient‐tailored stimulation protocols in order to reduce cancellations for excessive response, possibly improve pregnancy prospects and to reduce costs [1].

In conclusion, day 3 AMH has the potential to be a diagnostic marker for the prediction of poor response before COH during IVF with ICSI cycles. Overall, this biomarker is similar to hCG day E2 in predicting poor response but more predictive than day 3 FSH and AFC, and it has the potential to be incorporated into work‐up protocols to predict poor responders to COH with a sensitivity and a specificity of 78.9 and 73.8%, respectively, at the cut‐off of ≤2 ng/mL.

References

- 1. Broer SL, Mol B, Dólleman M, Fauser BC, Broekmans FJ. The role of anti‐Müllerian hormone assessment in assisted reproductive technology outcome. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 2010, 22, 193–201 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283384911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Navot D, Rosenwaks Z, Margalioth EJ. Prognostic assessment of female fecundity. Lancet, 1987, 19, 645–647 10.1016/S0140‐6736(87)92439‐1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fanchin R, Ziegler D, Olivennes F, Taieb J, Dzik A, Frydman R. Exogenous follicle stimulating hormone ovarian reserve test (EFORT): a simple and reliable screening test for detecting ‘poor responders’ in in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod, 1994, 9, 1607–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faddy MJ, Gosden RG. A model conforming the decline in follicle numbers to the age of menopause in women. Hum Reprod, 1996, 11, 1484–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lass A, Skull J, McVeigh E, Margara R, Winston RM. Measurement of ovarian volume by transvaginal sonography before ovulation induction with human menopausal gonadotrophin for in vitro fertilization can predict poor response. Hum Reprod, 1997, 12, 294–297 10.1093/humrep/12.2.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tomas C, Nuojua‐Huttunen S, Martikainen H. Pretreatment transvaginal ultrasound examination predicts ovarian responsiveness to gonadotrophins in in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod, 1997, 12, 220–223 10.1093/humrep/12.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall JE, Welt CK, Cramer DW. Inhibin A and inhibin B reflect ovarian function in assisted reproduction but are less useful at predicting outcome. Hum Reprod, 1999, 14, 409–415 10.1093/humrep/14.2.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Eijkemans MJ, Jong FH, Habbema JD, te Velde ER. Predictors of poor ovarian response in in vitro fertilization: a prospective study comparing basal markers of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril, 2002, 77, 328–336 10.1016/S0015‐0282(01)02983‐1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Lambalk CB. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update, 2006, 12, 685–718 10.1093/humupd/dml034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fiçicioglu C, Kutlu T, Baglam E, Bakacak Z. Early follicular antimüllerian hormone as an indicator of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril, 2006, 85, 592–596 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durlinger AL, Visser JA, Themmen AP. Regulation of ovarian function: the role of anti Mullerian hormone. Reproduction, 2002, 124, 601–609 10.1530/rep.0.1240601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Visser JA, Jong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti‐Müllerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction, 2006, 131, 1–9 10.1530/rep.1.00529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fréour T, Mirallié S, Colombel A, Bach‐Ngohou K, Masson D, Barrière P. Anti‐mullerian hormone: clinical relevance in assisted reproductive therapy. Ann Endocrinol, 2006, 67, 567–574 10.1016/S0003‐4266(06)73008‐6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Bancsi LF, Te Velde ER, Broekmans FJ. Antral follicle count in the prediction of poor ovarian response and pregnancy after in vitro fertilization: a meta‐analysis and comparison with basal follicle‐stimulating hormone level. Fertil Steril, 2005, 83, 291–301 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tarlatzis BC, Zepiridis L, Grimbizis G, Bontis J. Clinical management of low ovarian response to stimulation for IVF: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update, 2003, 9, 61–76 10.1093/humupd/dmg007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ulug U, Ben‐Shlomo I, Turan E, Erden HF, Akman MA, Bahceci M. Conception rates following assisted reproduction in poor responder patients: a retrospective study in 300 consecutive cycles. Reprod Biomed Online, 2003, 6, 439–443 10.1016/S1472‐6483(10)62164‐5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saldeen P, Källen K, Sundström P. The probability of successful IVF outcome after poor ovarian response. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2007, 86, 457–461 10.1080/00016340701194948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galey‐Fontaine J, Cédrin‐Durnerin I, Chaïbi R, Massin N, Hugues JN. Age and ovarian reserve are distinct predictive factors of cycle outcome in low responders. Reprod Biomed Online, 2005, 10, 94–99 10.1016/S1472‐6483(10)60808‐5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Disseldorp J, Lambalk CB, Kwee J, Looman CW, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC, Broekmans FJ. Comparison of inter‐ and intra‐cycle variability of anti‐Mullerian hormone and antral follicle counts. Hum Reprod, 2010, 25, 221–227 10.1093/humrep/dep366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jayaprakasan K, Campbell B, Hopkisson J, Johnson I, Raine‐Fenning N. A prospective, comparative analysis of anti‐Müllerian hormone, inhibin‐B, and three‐dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril, 2010, 93, 855–864 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singer T, Barad DH, Weghofer A, Gleicher N. Correlation of antimüllerian hormone and baseline follicle‐stimulating hormone levels. Fertil Steril, 2009, 91, 2616–2619 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gnoth C, Schuring AN, Friol K, Tigges J, Mallmann P, Godehardt E. Relevance of anti‐Mullerian hormone measurement in a routine IVF program. Hum Reprod, 2008, 23, 1359–1365 10.1093/humrep/den108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nardo LG, Christodoulou D, Gould D, Roberts SA, Fitzgerald CT, Laing I. Anti‐müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count in women enrolled in in vitro fertilization cycles: relationship to lifestyle factors, chronological age and reproductive history. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2007, 23, 486–493 10.1080/09513590701532815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. La Marca A, Giulini S, Tirelli A, Bertucci E, Marsella T, Xella S, Volpe A. Anti‐Müllerian hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod, 2007, 22, 766–771 10.1093/humrep/del421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seifer DB, Maclaughlin DT. Mullerian inhibiting substance is an ovarian growth factor of emerging clinical significance. Fertil Steril, 2007, 88, 539–546 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakhuda GS. The role of mullerian inhibiting substance in female reproduction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 2008, 20, 257–264 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282fe99f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bersinger NA, Wunder D, Birkhäuser MH, Guibourdenche J. Measurement of anti‐mullerian hormone by Beckman Coulter ELISA and DSL ELISA in assisted reproduction: differences between serum and follicular fluid. Clin Chim Acta, 2007, 384, 174–175 10.1016/j.cca.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]