Abstract

Freeze‐drying technology may one day be used to preserve mammalian spermatozoa indefinitely without cryopreservation. Freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa stored below 4°C for up to 1 year have maintained the ability to fertilize oocytes and support normal development. The maximum storage period for spermatozoa increases at lower storage temperatures. Freeze‐drying, per se, may reduce the integrity of chromosomes in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa, but induction of chromosomal damage is suppressed if spermatozoa are incubated with divalent cation chelating agents prior to freeze‐drying. Nevertheless, chromosomal damage does accumulate in spermatozoa stored at temperatures above 4°C. Currently, no established methods or strategies can prevent or reduce damage accumulation, and damage accumulation during storage is a serious obstacle to advances in freeze‐drying technology. Chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried human spermatozoa have roughly background levels of chromosomal damage after storage at 4°C for 1 month, but whether these spermatozoa can produce healthy newborns is unknown. The safety of using freeze‐dried human spermatozoa must be evaluated based on the risks of heritable chromosome and DNA damage that accumulates during storage.

Keywords: Chromosome, Cryopreservation, DNA damage, Freeze‐drying, Spermatozoa

Introduction

Cryopreservation with liquid nitrogen and storage at very low temperatures (−80°C) are used for many cell and tissue types and many purposes in a wide range of biological fields because these samples maintain many important characters and their genetic material is largely unaltered during cryopreservation and cryostorage. Nevertheless, sperm preservation methods that do not require liquid nitrogen‐based cryopreservation are needed for the following reasons. (1) Liquid nitrogen is not readily available in many countries and places (e.g., many developing countries, the Pacific Islands, space stations). (2) These cryopreserved samples are often destroyed or damaged because low‐temperature storage facilities fail due to human errors or loss of power. (3) These samples may be contaminated by pathogenic viruses that are stored in the same cryostorage facilities [1]. Although incidents of cross‐contamination are rare in cryobanks, it is difficult to make sure that it has not occurred yet [2]. For these reasons, advances in sperm preservation techniques that do not require liquid nitrogen or deep‐freezer storage may contribute to the safe preservation of the genome resources of mammalian species. (4) Potentially, freeze‐dried spermatozoa may be transported anywhere without any refrigerants, such as dry ice [3, 4].

This review focuses on freeze‐drying of mammalian spermatozoa, and particularly mouse and human spermatozoa. Recent progress and persistent problems associated with the methods used to maintain the integrity of DNA and chromosomes of the freeze‐dried spermatozoa are discussed.

Participation of motionless spermatozoa in fertilization

A method for freeze‐drying spermatozoa was published approximately a half century ago. More recently, Polge et al. [5] reported that the majority of freeze‐dried fowl spermatozoa were motile after rehydration, and in 1976, Larson and Graham [6] reported that some freeze‐dried bull spermatozoa were motile after rehydration. Moreover, even motionless spermatozoa can fertilize oocytes and support normal development with advances in intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [7]. These advances in ICSI led us to consider simple methods for mammalian spermatozoa preservation that do not require cryoprotectants [8] and the retrieval of sperm from frozen cadavers [9, 10]. Freeze‐dried spermatozoa need not be motile after rehydration; in laboratory mice, zygotes generated using ICSI and freeze‐dried sperm can develop into healthy, full‐term offspring [3]. Moreover, mice derived from the freeze‐dried spermatozoa gave rise to first‐ and second‐generation progeny with stable genomes [11]. Many studies have investigated freeze‐dried spermatozoa in mammalian species other than mice and humans. Most of these studies explored whether freeze‐dried spermatozoa from cattle [12, 13, 14, 15], dog [16], hamster [17], human [17, 18, 19, 20, 21], pig [22, 23], Rhesus monkey [24], rabbit [20, 25] or rat [26, 27, 28, 29] could develop to the pronuclear stage, the blastocyst stage, and/or to live birth.

For assisted reproduction in most species, ICSI must be introduced and improved to ensure that sperm that become non‐motile because of harsh isolation, preservation, or storage conditions can support normal development, although storage of freeze‐dried mammalian spermatozoa has great potential as an alternative to traditional nitrogen‐based cryopreservation.

Evaporative drying versus freeze‐drying

Procedures used to freeze‐dry mouse sperm usually include a freezing step (1–10 min) before the sublimation of water in the samples. A lyophilizer is generally used to sublimate the water. Glass ampoules containing the frozen sperm sample are connected to the lyophilizer, and a vacuum is applied at an inner pressure of approximately 1 m Torr for 12 h [3] or 0.04 mbar for 4 h [30]; alternatively, primary drying and subsequent secondary drying pressures (0.37 and 0.001 mbar, respectively) are applied to the ampoules [31].

Evaporative drying is another method used to prepare dried spermatozoa. Reportedly, evaporative drying of mouse spermatozoa is an exceptional method for preparing dried sperm specimens that eliminates the initial freezing step of freeze‐drying, which is likely to injure the spermatozoa [32, 33, 34, 35]. This evaporative drying method has been used primarily for laboratory mice sperm, and the technique has not been optimized for other mammalian species. Sperm suspension is applied to a glass slide and dried for 5 min at room temperature under a stream of nitrogen gas; notably, the time required to dry the sample is much shorter than the sublimation time required for freeze‐drying, which is at least 4 h. Moreover, the equipment required for the evaporative drying is simpler and cheaper than a lyophilizer [36]. It is unclear whether evaporative drying is superior to freeze‐drying for preserving mammalian spermatozoa, and studies on the long‐term maintenance of the dried spermatozoa preserved without cryostorage will address this question. Developmental competence of ICSI‐derived zygotes varies between laboratories and/or person doing ICSI. However, assessment of the chromosomal (DNA) integrity in dried spermatozoa will give us significant information on the ability of the spermatozoa to produce normal live offspring. Dried spermatozoa must have high levels of chromosomal (DNA) integrity to support normal development of ICSI‐derived zygotes.

Importance of chromosomal (DNA) integrity in freeze‐dried spermatozoa

The freezing, drying, and exposure to vacuum necessary to prepare freeze‐dried samples are harmful to spermatozoa. Chromosomal (DNA) damage is likely to be induced in the spermatozoa during each step. Therefore, two questions arise: (1) Can zygotes with paternally transmitted chromosome aberrations develop into live offspring? (2) Does the chromosomal damage generated in freeze‐dried spermatozoa pose genetic risks to successive generations?

Chromosomal damage induced in male germ cells contributes to early post‐implantation death [37], while induction of so‐called minor aberrations [38, 39] may be rather a serious event from the view point of genetic toxicology. Marchetti et al. [40] suggested that mouse embryos with a small number (less than four) of paternally transmitted chromosome aberrations experienced problems in later embryonic stages. Mouse zygotes with structural chromosome aberrations generated spontaneously via ICSI can develop into live offspring carrying chromosome alterations [41, 42].

The fate of the structurally aberrant chromosomes has been examined in somatic and germ cells. Stable structural chromosome aberrations, especially reciprocal translocations induced by gamma radiation, can persist in mouse bone marrow cells in vivo for at least 30 days after irradiation [43]. Unbalanced karyotypes with chromosome aberrations such as deletions or partial trisomy can be derived from chromatid‐type aberrations generated in cultured human lymphocytes [44]. Embryos with reciprocal translocations originating from mouse spermatozoa exposed to mutagenic compounds could develop into live offspring [40]. The frequency of embryos with structural chromosome aberrations originating from mouse spermatozoa exposed to γ‐ray‐irradiation (2 and 4 Gy) was reduced at the 2‐cell stage, but increased at the 4‐cell stage [45]. This observation indicated that DNA double‐strand breaks persisted in embryos through the first cell division and new chromosome aberrations formed in subsequent divisions [45]. Freeze‐dried spermatozoa with extremely damaged chromosomes (multiple aberrations) may inhibit blastocyst formation and post‐implantation development after ICSI. Some zygotes with fewer chromosome aberrations inherited from freeze‐dried spermatozoa are supposed to have the ability to develop into live offspring. In this case, some types of aberrant chromosomes will be transmitted to daughter cells (blastomeres). In the other case, some chromatid‐type aberrations may be converted to another aberration type during subsequent cell divisions. Live offspring produced from spermatozoa with severe chromosomal damage induced during improper freeze‐drying are at high risk for abnormal karyotypes and specific types of genetic alterations (e.g., microdeletions). Thus, improvement of chromosomal integrity in freeze‐dried spermatozoa is necessary not only for efficient production of live offspring, but also to maintain the genetic background of the animal strains being propagated with freeze‐dried spermatozoa. Moreover, freeze‐dried human spermatozoa must be free from de novo induction of chromosomal damage to prevent genetic disorders and related diseases.

Classification of chromosomal damage induced in freeze‐dried spermatozoa

Chromosomal integrity in spermatozoa is likely to be adversely affected by freeze‐drying, per se, and post‐freeze‐drying storage at room temperature. Types of chromosomal damage induced in freeze‐dried spermatozoa may be classified as primary chromosome damage (PCD) or accumulated chromosome damage (ACD). PCD is induced just after freeze‐drying. In contrast, ACD arises during post‐freeze‐drying storage [46]. The types of PCD and ACD reviewed here are DNA damage and/or aberrant chromatin remodeling [46, 47]. Currently, it is unknown whether PCD and ACD can include numerical chromosome aberrations because no studies have focused on these types of aberrations in embryos derived from freeze‐dried spermatozoa. Speculation on the mechanism causing PCD could be as follows. Hamster, human, and mouse spermatozoa contain an endogenous nuclease that requires Ca2+ and Mg2+ for enzymatic activity [48, 49]. The spermatozoa seemed to have the endogenous nuclease to cleave their own DNA. Fragmentation of sperm DNA was induced after sperm were incubated overnight in a medium supplemented with a detergent, Triton X‐100. The DNA fragments were similar in size to those generated by DNase I [49]. However, it is still unclear why the nuclease was activated by the detergent. Reportedly, DNA fragmentation was also observed in frozen‐thawed human spermatozoa [49] and in sonicated mouse spermatozoa following storage in culture media [50]; both observations indicate that the nuclease was activated.

Moreover, PCD was induced severely when spermatozoa that had been freeze‐dried in a standard culture medium containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ were microinjected into oocytes [30]. Electron microscopic examination showed that the sperm plasma membrane was removed upon treatment with Triton X‐100 [51] and ruptured after freeze‐drying [3]. Therefore, nuclei in freeze‐dried spermatozoa must be exposed to high concentration of Ca2+ via the ruptured plasma membrane because oocytes subjected to ICSI show normal Ca2+ oscillations [52]. Thus, it is likely that the Ca2+‐ and Mg2+‐dependent nuclease would be activated following damage to the plasma membrane and the subsequent influx of cations into sperm nuclei.

Chromatin of mouse testicular spermatozoa is more vulnerable to freeze‐drying than chromatin of epididymal spermatozoa [53]. Induction of PCD in testicular spermatozoa can be suppressed by treating the spermatozoa with diamide, an oxidizing agent that forms disulfide bonds (–S–S–) from sulfhydryl (–SH) groups in sperm protamines [53]. In testicular spermatozoa, sperm DNA in SS‐poor chromatin will be more exposed to the Ca2+‐ and Mg2+‐dependent nuclease than DNA in SS‐rich chromatin.

Suppression of PCD induction

In 2001, it was discovered that a simple chelating solution suppressed PCD during freeze‐drying of mouse spermatozoa. In contrast, PCD was severe in mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in culture medium without cryoprotection [30]. Presumably, the chelating agent is an active component of the solution. The solution is composed of 50 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 50 mM EGTA (ethylenglycol‐bis(β‐aminoethyl ether)‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic acid), and 10 mM Tris–HCl (EGTA Tris–HCl buffered solution: ETBS, pH 8.2–8.4) and is usually used to suspend naked DNA preparation for molecular biology protocols. The EGTA presumably inhibits the activity of Ca2+‐dependent nuclease by chelating Ca2+, and a modified version of the solution adjusted to pH 8.0 was also developed [54]. Exclusion of NaCl from the solution may improve the developmental competence of zygotes derived from the freeze‐dried spermatozoa. One such solution is TE buffer [29, 39]. TE buffer consists of 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid) and 10 mM Tris–HCl. The efficacy of specific chelating solutions for freeze drying of spermatozoa probably differs for different animal species, and solutions optimized for different species are likely to differ in some components and the concentrations of shared components. Reportedly, mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in TE buffer supported the development of more offspring than those freeze‐dried in ETBS [39]. In contrast, boar spermatozoa freeze‐dried in the ETBS seemed to support in vitro development of embryos better than boar spermatozoa freeze‐dried in EDTA‐based solutions [23].

The EDTA is a standard supplement in cell culture media. EDTA binds a wide range of divalent cations, including Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Zn2+, but EGTA preferentially binds Ca2+. Moreover, EGTA is not an effective chelating agent for Zn2+. In human spermatozoa, Zn2+ is presumed to play an important role in stabilizing sperm chromatin structure at ejaculation [55, 56]. Although EGTA chelates Ca2+ and, therefore, prevents activation of endogenous Ca2+‐dependent nuclease in spermatozoa, it does not affect the zinc status of sperm chromatin. In fact, fertile sperm donors have higher zinc content in their sperm chromatin than infertile men [55].

Mouse spermatozoa can be suspended in modified ETBS and kept in a refrigerator for 1 week before freeze‐drying. The modified ETBS (50 mM EGTA + 100 mM Tris–HCl), unlike the original ETBS, does not contain NaCl [21]. Mouse spermatozoa suspended in the original ETBS lose mobility after incubation at 37°C for 10 min, whereas the majority of spermatozoa suspended in the modified ETBS maintain mobility after incubation at 37°C for 10 min. The modified ETBS allows for efficient collection of many motile spermatozoa. The modified ETBS seemed to be less toxic to mouse spermatozoa than original ETBS, and the modified ETBS can be used for freeze‐drying of mouse cumulus and ES cells [57].

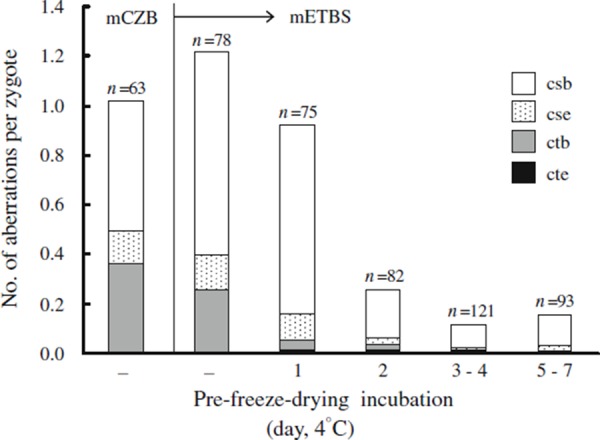

Interestingly, induced PCD is very severe in mouse spermatozoa that had been briefly suspended in modified ETBS just before freeze‐drying. However, the level of PCD decreases as the pre‐freeze‐drying incubation time in modified ETBS is increased (up to 1 week at 4°C) (Fig. 1) [21].

Figure 1.

Primary chromosome damage (PCD) induced after freeze‐drying of mouse spermatozoa. Spermatozoa freeze‐dried in modified CZB (mCZB) and modified ETBS (mETBS) were stored at 4°C for up to 63 days [30] or up to 14 days [21], respectively. The PCD decreases as pre‐freeze‐drying incubation time in the mETBS increases. csb chromosome break, cse chromosome exchange, ctb chromatid break, cte chromatid exchange. Aberrations such as chromosome fragmentation and multiple aberrations (10 or more aberrations per zygote) that could not be counted were excluded from the data set

Types of chromosome aberrations associated with PCD

PCD is observed in mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in modified CZB medium [58, 59]. The frequency of each type of chromosome aberration in spermatozoa freeze‐dried in CZB corresponds roughly to that in spermatozoa freeze‐dried in modified ETBS without pre‐freeze‐drying incubation (Fig. 1). Most of the PCD is due to chromosome breaks (csb). The frequency of zygotes with other types of aberrations [e.g., chromosome exchange (cse), including dicentric chromosomes, ring chromosomes, and reciprocal translocation] might be underestimated because the reciprocal translocations are not readily detected with conventional staining methods. The frequency of zygotes with csb decreases as the duration of the pre‐freeze‐drying incubation increases; consequently, overall levels of PCD decrease (Fig. 1).

Recently, Bignold [60] proposed mechanisms for the induction of clastogen‐induced structural chromosome aberrations. The model invoked a failure in DNA‐enzyme tethering during enzyme‐created DNA strand breaks. According to the model, formation of chromosome aberrations initiates with DNA double‐strand breaks (DSBs) created by DNA‐repair enzyme before DNA synthesis.

It is important to determine whether the chromosome breaks associated with PCD formed from DSBs generated in sperm DNA directly by freeze‐drying. The origin of PCD can be assessed using single cell gel electrophoresis assay (comet assay) [46]. The comet assay is a well‐known technique used to detect DNA damage in situ. The standard comet assay includes an alkali treatment of cells embedded in agarose gel on glass slides; this alkali treatment unwinds DNA, and the cells are then subjected to electrophoresis in an alkaline solution (pH 13 or higher). A modified version, the comet assay with the A/N protocol, consists of alkaline DNA unwinding and electrophoresis at neutral pH [61, 62, 63]. The alkaline comet assay reveals single‐strand breaks (SSBs), DSBs, and alkaline‐labile sites (ALS) in DNA in somatic and germ cells [64, 65, 66]. Another version, called the neutral comet assay, reveals primarily DSBs; the electrophoresis is performed at neutral pH and without the alkali pre‐treatment [67, 68].

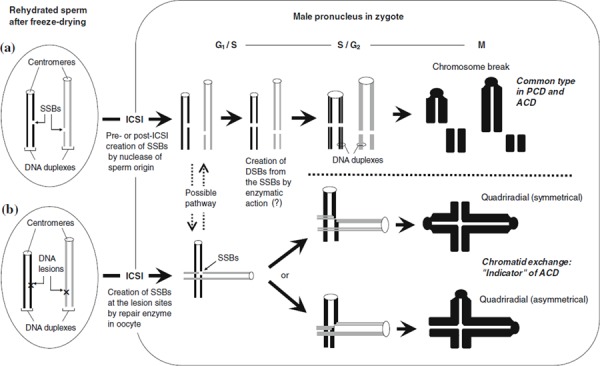

The comet assay with the A/N protocol revealed significant DNA migration in freeze‐dried spermatozoa indicating PCD, but the neutral comet assay did not reveal any damage [46]. According to hypothetical explanation for the induction of PCD, endogenous nuclease like DNase I, mentioned previously, might create “nicks” (i.e., SSB) in sperm DNA before or just after microinjection of freeze‐dried spermatozoa into the oocytes. Immediately after SSB creation, an as‐yet unidentified enzyme would convert the SSBs to DSBs before DNA synthesis. Enzymes such as single‐strand‐specific nuclease (e.g., S1 nuclease) might cleave single‐stranded DNA at the SSBs (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of hypothetical explanations of primary chromosome damage (PCD) and accumulative chromosome damage (ACD) in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa. a A DNA single‐strand break (SSB) was probably created by enzymatic action before or immediately after intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and resulted in initiation of PCD. b Unidentified DNA lesions other than SSBs may accumulate in DNA of freeze‐dried spermatozoa during their storage. Some SSBs created at lesions may not be converted to DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). The SSBs that persisted until DNA replication stage may be responsible for the formation of chromatid‐type aberrations

Accumulated chromosome damage

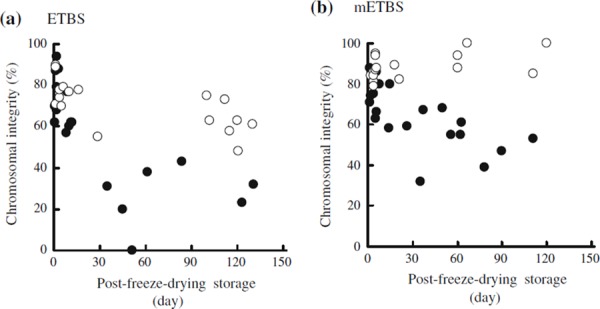

Chelating solutions used for freeze‐drying sperm play an important role in suppressing the induction of PCD. Mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in the modified ETBS seemed to have better chromosomal integrity than those freeze‐dried in the original ETBS when stored at 4 and 25°C for up to 3 months (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, neither the original ETBS nor modified ETBS seem to inhibit the accumulation of DNA damage in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa stored at room temperatures. DNA damage in the freeze‐dried spermatozoa, i.e. accumulation of as‐yet unknown DNA modifications during storage, is referred to as accumulated chromosome damage (ACD). Identification of the causes of ACD should lead to vast improvement in the developmental competence of oocytes injected with freeze‐dried spermatozoa stored at room temperature.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal integrity of zygotes derived from mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in ETBS (a) and modified ETBS (b). Frequency of zygotes with normal chromosome constitution was expressed as the integrity per freeze‐dried sample. Freeze‐dried spermatozoa were preserved at 4°C (open circles) or room temperatures of 22–24°C (filled circles) (a) and at 4°C (open circles) or 25°C (filled circles) (b)

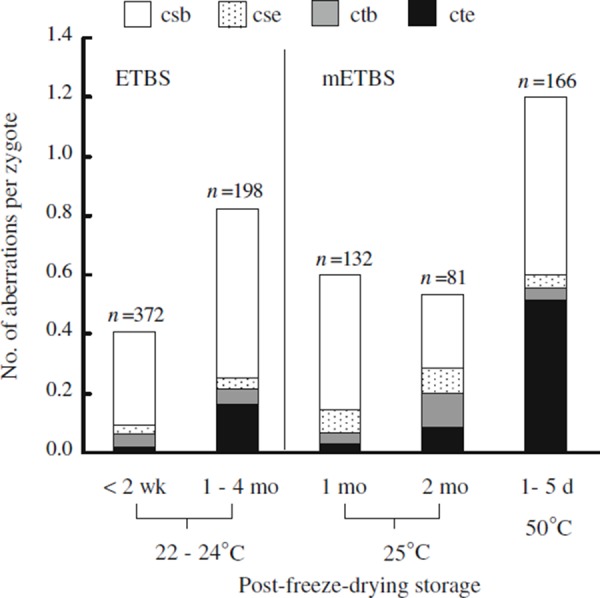

Recent findings [46] suggest that chromosome breaks were the most common type of ACD (Fig. 4). However, when mouse oocytes were injected with spermatozoa freeze‐dried in original ETBS, the frequency of chromatid exchange (the number of chromatid exchanges per zygote) increased after storage of sperm for 1–4 months at 22–24°C. Induction of chromatid exchanges seemed to be enhanced by heat‐stress (50°C, 1–5 days) (Fig. 4). DNA damage in sperm induced by heat‐stress was not detected using the neutral comet assay, but it was detected using the comet assay with the A/N protocol [46]. The type of damage induced directly in sperm DNA would be not the DSBs that are responsible for the induction of chromosome breaks resulting in chromosomal aberrations. SSBs or other types of DNA lesions, not including DSB, were probably associated with the formation of chromatid exchanges after DNA replication (Fig. 2b). These chromatid exchanges, also called quadriradials, are thought to form by the rejoining of two SSBs generated in two different chromosomes. Most of the SSBs created in sperm DNA will convert to DSBs via repair and/or replication enzymes present in the oocytes cytoplasm [69] to form the chromosome breaks that cause ACD. However, higher temperatures may induce steric alterations in the sperm chromatin or DNA [70, 71]. These hypothetical steric alterations in sperm DNA or chromatin could interfere with the binding of specific proteins (or enzymes) that are required for chromosome condensation [72] and with the conversion of SSBs to DSBs. The chromatid exchanges would form from the SSBs that persisted until the DNA replication stage (Fig. 2) [46].

Figure 4.

Accumulated chromosome damage (ACD) in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa. The spermatozoa freeze‐dried in ETBS and modified ETBS (mETBS) were stored at room temperature or at 50°C. When using mETBS, the spermatozoa were freeze‐dried after pre‐freeze‐drying incubation in mETBS at 4 or 25°C for 3–7 days [46]. csb chromosome break, cse chromosome exchange, ctb chromatid break, cte chromatid exchange. Aberrations such as chromosome fragmentation and multiple aberrations (10 or more aberrations per zygote) that could not be counted were excluded from the data set

Developmental competence of mouse spermatozoa preserved without cryostorage

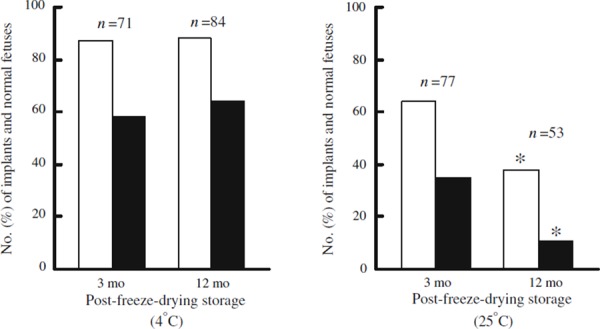

The maximum time that freeze‐dried spermatozoa can be stored and maintain the ability to support normal development of embryos, fetuses, and live offspring was estimated by several groups. Freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa can be stored indefinitely at −80°C without deterioration [73]. Li et al. [34] estimated that 90% of mouse spermatozoa preserved by evaporative drying lost the ability to produce offspring after storage at −80°C for 173 weeks (3.6 years) or storage at 4°C for 20 weeks (5 months). In contrast, other groups demonstrated that freeze‐dried spermatozoa had no decline in the ability to support post‐implantation development of zygotes during at least 1 year of storage at 4°C [74]. After 1.5 years of storage at 4°C, freeze‐dried sperm were used to generate a sufficient number of healthy progeny to establish a breeding colony [74]. In addition, mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in modified ETBS retained the ability to support development of normal fetuses when preserved at 4°C for up to 12 months (Fig. 5a) [21]. Nonetheless, there is no evidence that freeze‐dried spermatozoa can be preserved indefinitely at 4°C. Freeze‐dried spermatozoa deteriorate to a greater or lesser degree with increasing storage time, though the time that sperm maintain their integrity in storage differs between the protocols used to dry the spermatozoa (e.g., pressure and time for vacuuming, medium for suspending spermatozoa, size of vials, lyophilizer).

Figure 5.

Post‐implantation development of mouse (B6D2F1) oocytes microinjected with mouse (B6D2F1) spermatozoa freeze‐dried after pre‐freeze‐drying incubation in modified ETBS at 4°C for 5–7 days (a) [21] and 25°C for 4–7 days (b) (unpublished). Post‐freeze‐drying samples were stored for 3 and 12 months at the same temperatures as the pre‐freeze‐drying incubation. The embryos were transferred into CD‐1 females (albino) on the first day of pseudopregnancy after being mated with vasectomized CD‐1 males (albino). Number of implants (white bars) is consistent with total number of normal fetuses (black bars) and resorption sites examined on 14‐ or 18‐day gestation. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the data obtained from the spermatozoa preserved for 3 months by χ2 comparison

How long can freeze‐dried spermatozoa be preserved at room temperature? Freeze‐dried spermatozoa stored for 1 month at 25°C were less able to support development of normal live offspring than those stored for 3 months at 4°C [3]. Moreover, freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa stored at 24°C for 5 months did not produce offspring [75]. Kawase et al. [73] estimated that mouse oocytes injected with freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa stored at 25°C for 1 month seldom developed into blastocysts. Most mouse spermatozoa preserved by evaporative drying and stored at 22°C for 1 month lost the ability to support the development of blastocysts [33, 34]. In contrast, a low proportion (11%) of 2‐cell embryos derived from mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in modified ETBS and stored for 12 months at 25°C developed into normal day‐18 fetuses (Fig. 5b). Further improvement in the solutions used during freeze‐drying may help in preventing or delaying the decline of chromosomal integrity.

Some studies analyzed the developmental competence of oocytes injected with unfrozen spermatozoa stored at room temperature. Mouse epididymal spermatozoa stored for 7 days at 22°C in TYH medium [76] lost motility, plasma membrane integrity, and acrosome integrity [77]. However, some oocytes fertilized in vitro by the spermatozoa stored for up to 3 days did develop into normal fetuses [77]. Van Tyuan et al. [78] reported that developmental competence of mouse oocytes microinjected with mouse spermatozoa stored at 27°C in KSOM medium containing amino acids and BSA [79] declined as the sperm storage period increase to 15 days, at which point the developmental competence reached zero. Spermatozoa taken from whole cauda epididymidis that had been preserved for 1 year at room temperature in powdered NaCl could activate oocytes [80]; however, most of these spermatozoa failed to support the development of zygotes into morula or blastocysts when the sperm were stored for 1 week–1 month after isolation [80]. Sperm deterioration was never stopped by freeze‐drying and any of the methods mentioned above other than freeze‐drying.

Based on these studies, the dehydration, freeze‐drying, and evaporative drying methods used to preserve mouse spermatozoa do not effectively prepare the spermatozoa for more than 1 month of storage at room temperature.

Heat‐resistant nature of sperm‐born oocyte‐activating factor(s) in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa

What do unfrozen spermatozoa lose during storage at ambient or higher temperatures? The majority of spermatozoa preserved in ETBS for 9 days at room temperatures (22–24°C) lose the ability to activate oocytes [81]. Some spermatozoa preserved in KSOM medium with amino acids and BSA and stored at 27°C maintain the ability to activate oocytes for a few weeks [78]. Perry et al. [82] demonstrated that mouse spermatozoa suspended in NIM medium lose the ability to activate oocytes if the spermatozoa are incubated at temperatures over 44°C for 30 min. Mouse spermatozoa incubated at 56°C (a temperature that inactivates HIV) for 30 min cannot activate oocytes [83]. In contrast, freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa heated continuously at 50°C for up to 7 days maintained the ability to activate oocytes [73]. Liu et al. [52] demonstrated that most oocytes microinjected with freeze‐dried bovine spermatozoa heated at 56°C for 15 min exhibited a normal pattern of calcium oscillations. Sperm‐borne oocyte‐activating factor(s) (SOAF) [51] are likely to acquire heat resistance after freeze‐drying, but we have no information on the inner temperatures of the glass ampoules that are vacuum‐sealed after freeze‐drying. At room temperature, the SOAF in freeze‐dried spermatozoa may not be destroyed even after long‐term preservation (>5 months) [39]. The most likely candidate for the SOAF is protein‐based and sperm‐specific, phospholipase C zeta [84, 85, 86]. Higher order structures composed of protein molecules should readily denature as temperatures rise. Thus, the characteristic of water‐free sperm sample preserved under a vacuum is not well established.

Gamma‐ray‐resistance of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa

It will be necessary to examine the effect of physical circumstances such as ultraviolet light, ionizing and non‐ionizing radiation to deteriorate freeze‐dried spermatozoa. We reported that chromosomes of mouse spermatozoa freeze‐dried in ETBS were more resistant to γ‐ray‐irradiation (up to 8 Gy) than those of the spermatozoa suspended in ETBS [87]. This means that no significant difference of chromosomal integrity was observed between freeze‐dried spermatozoa that had been exposed to γ‐ray‐irradiation and those that had not been exposed to the irradiation [87]. The resistance to ionizing irradiation may be a very important to maintaining the integrity of mammalian genomes during long‐term storage of gametes as sperm preservation techniques advance.

Chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried human spermatozoa

To preserve the fertility of male patients undergoing cancer treatments; patients’ spermatozoa are often cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen before chemo‐ and radiation therapies. Potentially, some spermatozoa can be freeze‐dried and stored as a secondary stock to be used in case of failure of the cryostorage facility. However, pilot studies to determine the proper protocol for freeze‐drying human spermatozoa require many oocytes from laboratory animals, and there is little or no report on the relationship between developmental competency and chromosomal (DNA) integrity of freeze‐dried human spermatozoa. Rudak et al. [88] directly analyzed human sperm chromosomes following in vitro fertilization of golden hamster oocytes with the fresh spermatozoa. In 1976, Uehara and Yanagimachi [19] demonstrated that freeze‐dried human spermatozoa retain the ability to form sperm and oocyte pronuclei after injection into hamster oocytes. Katayose et al. [17] demonstrated that freeze‐dried human and hamster spermatozoa stored at 4°C between 6 and 12 months retain the ability to form sperm pronuclei after injection into hamster oocytes. In contrast, freeze‐dried spermatozoa stored at 25°C retain the ability to form pronuclei for no more than 2 weeks of storage. These experiments indicated that pronuclear formation could be used as an assay in studies investigating the effects of preservation techniques and storage temperatures on damage accumulation in freeze‐dried human spermatozoa. Hoshi et al. [20] reported that there was no significant difference between sperm pronuclear formation rates in hamster oocytes injected with freeze‐dried (85%) and non‐freeze‐dried human spermatozoa (89%). These findings indicated that human oocytes injected with freeze‐dried human spermatozoa may have the potential to develop into embryonic stages past the pronuclear stage. In contrast, freeze‐dried human spermatozoa deteriorate within 2 weeks of their preservation when stored at ambient temperatures and are unable to support pronuclear formation.

To analyze human chromosomes without confusing chromosomes of mouse oocytes, freeze‐dried human spermatozoa were injected into enucleated mouse oocytes [21]. In the protocol followed to freeze‐dry the spermatozoa, a semen sample is allowed to liquefy at 37°C for 30 min, and then a 0.5‐ml aliquot is carefully placed at the bottom of a small test tube containing 2 ml of modified ETBS pre‐warmed to 37°C. Under these conditions, most mouse and human spermatozoa swim into the modified ETBS and remain motile for 10 min following the initiation of swimming. In contrast, mouse spermatozoa that swim into original ETBS stop moving within 10 min [30]. Therefore, modified ETBS may be superior to original ETBS for collection of the motile human spermatozoa prior to freeze‐drying. Furthermore, the pre‐freeze‐drying incubation in modified ETBS is unnecessary for suppressing the induction of PCD in freeze‐dried human spermatozoa. It may be that EGTA penetrates human sperm nuclei more readily than mouse sperm nuclei.

Chromosome analysis of enucleated oocytes injected with human spermatozoa freeze‐dried without pre‐freeze‐drying incubation demonstrated that 86–92% of the sperm‐injected oocytes reached metaphase of the first mitosis [21]. These rates are similar to the rate (89.4%) previously reported for enucleated mouse oocytes injected with fresh human spermatozoa [89]. Of the sperm‐injected oocytes that reached metaphase, 91.1% possessed normal chromosome constitution [21]. This level of chromosomal integrity is almost same as background levels (roughly, 86–95%) reported for IVF using golden hamster oocytes and fresh human spermatozoa [90, 91, 92, 93] and for ICSI of morphologically normal spermatozoa obtained from fertile or healthy men into mouse oocytes [94, 95, 96, 97]. Moreover, results of multicolor multi‐chromosome FISH analysis in human spermatozoa indicated that advanced male age increases the frequency of structural chromosome aberrations in sperm nuclei [98]. The overall mean frequency of spermatozoa with aberrations is 5.8%, and the aberrations are limited to structurally unbalanced rearrangements. Therefore, PCD induced in human spermatozoa is negligible as long as the spermatozoa are freeze‐dried properly.

Freeze‐drying and human spermatozoa with large vacuoles

The morphology of the freeze‐dried spermatozoa may be important when selecting a spermatozoon for ICSI. The presence of large vacuoles in human spermatozoa has been noted for many years. In 1973, Bedford et al. [99] found a vacuole‐like structure in human sperm heads that decondensed upon treatment with SDS and DTT. Berkovitz et al. [100] reported that microinjection of vacuolated spermatozoa into oocytes reduced the pregnancy rate and was associated with early spontaneous abortion. Perdrix et al. [101] demonstrated that numerical chromosome aberrations and chromatin condensation defects occurred more frequently in teratozoospermic spermatozoa with large vacuoles than in those without large vacuoles. In addition, the presence of the large vacuoles in spermatozoa seems to be correlated with DNA fragmentation [102]. Human spermatozoa without large vacuoles can be selected in real time for assisted fertilization using morphologically‐selected sperm for injection; this procedure has been named intracytoplasmic morphologically‐selected sperm injection (IMSI). Reportedly, IMSI can also be used to select spermatozoa without aneuploidy [103]. In contrast, frequency of day 2 embryos derived from human spermatozoa showed no significant difference between conventional ICSI and IMSI [104]. Moreover, the presence of large vacuoles in sperm was not correlated with induction of structural chromosome aberrations and DNA damage in fertile donors and ICSI patients [105].

While some reports suggested that the vacuolated spermatozoa were correlated with chromosomal abnormalities in sperm, there is no direct evidence that large vacuoles partially or exclusively cause the chromosomal or DNA damage. It is unknown whether levels of PCD and ACD are higher in freeze‐dried spermatozoa with large vacuoles than those with small or no vacuoles. In addition, it may be important to determine how the chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried human spermatozoa from fertile donors differs from freeze‐dried spermatozoa from infertile patients and how chromosomal integrity differs between semen samples consisted of vacuole‐rich and vacuole‐poor sperm populations.

Conclusion

Examination of the chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried human and mouse spermatozoa may play an important role in improving the developmental competence of zygotes derived from these spermatozoa. PCD in mouse spermatozoa induced by freeze‐drying can be suppressed by suspending the spermatozoa in chelating solutions prior to freeze‐drying. In contrast, no current method can suppress ACD in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa during post‐freeze‐drying storage, especially during storage at room temperature. Mouse fetuses were produced using freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa stored at 25°C for up to 1 year; however, increases in the rate of implantation loss indicated that ACD in spermatozoa occurred during storage. Moreover, the fetuses produced with freeze‐dried spermatozoa subjected to long‐term storage may have higher risks of genetic alterations. A better understanding the causes of ACD is an important first step in suppressing or preventing ACD in freeze‐dried spermatozoa.

Freeze‐drying may become available for preserving human spermatozoa in the future. Currently, however, we lack sufficient information on ACD in freeze‐dried human spermatozoa. Moreover, whether chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried human spermatozoa differs between the spermatozoa with and without vacuoles is unknown. Therefore, we need to consider that freeze‐dried spermatozoa stored for long‐term periods may increase the risk of genetic alteration transmittable to newborns.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (1668120 to H.K.), and by The Akiyama Foundation (to H.K.).

References

- 1. Tedder RS, Zuckerman MA, Goldstone AH, Hawkins AE, Fielding A, Briggs EM et al. Hepatitis B transmission from contaminated cryopreservation tank. Lancet, 1995, 346, 137–140 10.1016/S0140‐6736(95)91207‐X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomlinson M, Sakkas D. Is a review of standard procedures for cryopreservation needed?: safe and effective cryopreservation—should sperm banks and fertility centres move toward storage in nitrogen vapour?. Hum Reprod, 2000, 15, 2460–2463 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Development of normal mice from oocytes injected with freeze‐dried spermatozoa. Nat Biotechnol, 1998, 16, 639–641 10.1038/nbt0798‐639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kawase Y, Tachibe T, Jishage K, Suzuki H. Transportation of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa under different preservation conditions. J Reprod Dev, 2007, 53, 1169–1174 10.1262/jrd.19037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polge C, Smith AU, Parkes AS. Revival of spermatozoa after vitrification and dehydration at low temperatures. Nature, 1949, 164, 666 10.1038/164666a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larson EV, Graham EF. Freeze‐drying of spermatozoa. Dev Biol Stand, 1976, 36, 343–348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the mouse. Biol Reprod, 1995, 52, 709–720 10.1095/biolreprod52.4.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wakayama T, Whittingham DG, Yanagimachi R. Production of normal offspring from mouse oocytes injected with spermatozoa cryopreserved with or without cryoprotection. J Reprod Fertil, 1998, 112, 11–17 10.1530/jrf.0.1120011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kishikawa H, Tateno H, Yanagimachi R. Fertility of mouse spermatozoa retrieved from cadavers and maintained at 4 degrees C. J Reprod Fertil, 1999, 116, 217–222 10.1530/jrf.0.1160217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogonuki N, Mochida K, Miki H, Inoue K, Fray M, Iwaki T et al. Spermatozoa and spermatids retrieved from frozen reproductive organs or frozen whole bodies of male mice can produce normal offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2006, 103, 13098–13103 10.1073/pnas.0605755103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li MW, Willis BJ, Griffey SM, Spearow JL, Lloyd KC. Assessment of three generations of mice derived by ICSI using freeze‐dried sperm. Zygote, 2009, 17, 239–251 10.1017/S0967199409005292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keskintepe L, Pacholczyk G, Machnicka A, Norris K, Curuk MA, Khan I et al. Bovine blastocyst development from oocytes injected with freeze‐dried spermatozoa. Biol Reprod, 2002, 67, 409–415 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martins CF, Dode MN, Báo SN, Rumpf R. The use of the acridine orange test and the TUNEL assay to assess the integrity of freeze‐dried bovine spermatozoa DNA. Genet Mol Res, 2007, 6, 94–104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martins CF, Báo SN, Dode MN, Correa GA, Rumpf R. Effects of freeze‐drying on cytology, ultrastructure, DNA fragmentation, and fertilizing ability of bovine sperm. Theriogenology, 2007, 67, 1307–1315 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abdalla H, Hirabayashi M, Hochi S. Demethylation dynamics of the paternal genome in pronuclear‐stage bovine zygotes produced by in vitro fertilization and ooplasmic injection of freeze‐thawed or freeze‐dried spermatozoa. J Reprod Dev, 2009, 55, 433–439 10.1262/jrd.20229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watanabe H, Asano T, Abe Y, Fukui Y, Suzuki H. Pronuclear formation of freeze‐dried canine spermatozoa microinjected into mouse oocytes. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2009, 26, 531–536 10.1007/s10815‐009‐9358‐y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katayose H, Matsuda J, Yanagimachi R. The ability of dehydrated hamster and human sperm nuclei to develop into pronuclei. Biol Reprod, 1992, 47, 277–284 10.1095/biolreprod47.2.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sherman JK. Freezing and freeze‐drying of human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril, 1954, 5, 357–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uehara T, Yanagimachi R. Microsurgical injection of spermatozoa into hamster eggs with subsequent transformation of sperm nuclei into male pronuclei. Biol Reprod, 1976, 15, 467–470 10.1095/biolreprod15.4.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoshi K, Yanagida K, Katayose H, Yazawa H. Pronuclear formation and cleavage of mammalian eggs after microsurgical injection of freeze‐dried sperm nuclei. Zygote, 1994, 2, 237–242 10.1017/S0967199400002033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kusakabe H, Kamiguchi Y, Yanagimachi R. Mouse and human spermatozoa can be freeze‐dried without damaging their chromosomes. Hum Reprod, 2008, 23, 233–239 10.1093/humrep/dem252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwon IK, Park KE, Niwa K. Activation, pronuclear formation, and development in vitro of pig oocytes following intracytoplasmic injection of freeze‐dried spermatozoa. Biol Reprod, 2004, 71, 1430–1436 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakai M, Kashiwazaki N, Takizawa A, Maedomari N, Ozawa M, Noguchi J et al. Effects of chelating agents during freeze‐drying of boar spermatozoa on DNA fragmentation and on developmental ability in vitro and in vivo after intracytoplasmic sperm head injection. Zygote, 2007, 15, 15–24 10.1017/S0967199406003935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sánchez‐Partida LG, Simerly CR, Ramalho‐Santos J. Freeze‐dried primate sperm retains early reproductive potential after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril, 2008, 89, 742–745 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu JL, Kusakabe H, Chang CC, Suzuki H, Schmidt DW, Julian M et al. Freeze‐dried sperm fertilization leads to full‐term development in rabbits. Biol Reprod, 2004, 70, 1776–1781 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirabayashi M, Kato M, Ito J, Hochi S. Viable rat offspring derived from oocytes intracytoplasmically injected with freeze‐dried sperm heads. Zygote, 2005, 13, 79–85 10.1017/S096719940500300X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaneko T, Kimura S, Nakagata N. Offspring derived from oocytes injected with rat sperm, frozen or freeze‐dried without cryoprotection. Theriogenology, 2007, 68, 1017–1021 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hochi S, Watanabe K, Kato M, Hirabayashi M. Live rats resulting from injection of oocytes with spermatozoa freeze‐dried and stored for one year. Mol Reprod Dev, 2008, 75, 890–894 10.1002/mrd.20825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaneko T, Kimura S, Nakagata N. Importance of primary culture conditions for the development of rat ICSI embryos and long‐term preservation of freeze‐dried sperm. Cryobiology, 2009, 58, 293–297 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kusakabe H, Szczygiel MA, Whittingham DG, Yanagimachi R. Maintenance of genetic integrity in frozen and freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98, 13501–13506 10.1073/pnas.241517598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kawase Y, Hani T, Kamada N, Jishage K, Suzuki H. Effect of pressure at primary drying of freeze‐drying mouse sperm reproduction ability and preservation potential. Reproduction, 2007, 133, 841–846 10.1530/REP‐06‐0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bhowmick S, Zhu L, McGinnis L, Lawitts J, Nath BD, Toner M et al. Desiccation tolerance of spermatozoa dried at ambient temperature: production of fetal mice. Biol Reprod, 2003, 68, 1779–1786 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McGinnis LK, Zhu L, Lawitts JA, Bhowmick S, Toner M, Biggers JD. Mouse sperm desiccated and stored in trehalose medium without freezing. Biol Reprod, 2005, 73, 627–633 10.1095/biolreprod.105.042291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li MW, Biggers JD, Elmoazzen HY, Toner M, McGinnis L, Lloyd KC. Long‐term storage of mouse spermatozoa after evaporative drying. Reproduction, 2007, 133, 919–929 10.1530/REP‐06‐0096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elmoazzen HY, Lee GY, Li MW, McGinnis LK, Lloyd KC, Toner M et al. Further optimization of mouse spermatozoa evaporative drying techniques. Cryobiology, 2009, 59, 113–115 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biggers JD. Evaporative drying of mouse spermatozoa. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19(Suppl 4):4338. [PubMed]

- 37. Singer TM, Lambert IB, Williams A, Douglas GR, Yauk CL. Detection of induced male germline mutation: correlations and comparisons between traditional germline mutation assays, transgenic rodent assays and expanded simple tandem repeat instability assays. Mutat Res, 2006, 598, 164–193 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Szczygiel MA, Ward WS. Combination of dithiothreitol and detergent treatment of spermatozoa causes paternal chromosomal damage. Biol Reprod, 2002, 67, 1532–1537 10.1095/biolreprod.101.002667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaneko T, Nakagata N. Improvement in the long‐term stability of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa by adding of a chelating agent. Cryobiology, 2006, 53, 279–282 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marchetti F, Bishop JB, Cosentino L, Moore D 2nd, Wyrobek AJ. Paternally transmitted chromosomal aberrations in mouse zygotes determine their embryonic fate. Biol Reprod, 2004, 70, 616–624 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tateno H, Kamiguchi Y. Evaluation of chromosomal risk following intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the mouse. Biol Reprod, 2007, 77, 336–342 10.1095/biolreprod.106.057778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tateno H. Chromosome aberrations in mouse embryos and fetuses produced by assisted reproductive technology. Mutat Res, 2008, 657, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Spruill MD, Ramsey MJ, Swiger RR, Nath J, Tucker JD. The persistence of aberrations in mice induced by gamma radiation as measured by chromosome painting. Mutat Res, 1996, 356, 135–145 10.1016/0027‐5107(95)00218‐9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kusakabe H, Takahashi T, Tanaka N. Chromosome‐type aberrations induced in chromosome 9 after treatment of human peripheral blood lymphocytes with mitomycin C at the G(0) phase. Cytogenet Cell Genet, 1999, 85, 212–216 10.1159/000015295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tateno H, Kusakabe H, Kamiguchi Y. Structural chromosomal aberrations, aneuploidy, and mosaicism in early cleavage mouse embryos derived from spermatozoa exposed to γ‐rays. Int J Radiat Biol, 2011, 87, 320–329 10.3109/09553002.2011.530334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kusakabe H, Tateno H. Characterization of chromosomal damage accumulated in freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa preserved under ambient and heat stress conditions. Mutagenesis, 2011, 26, 447–453 10.1093/mutage/ger003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tateno H, Kamiguchi Y. How long do parthenogenetically activated mouse oocytes maintain the ability to accept sperm nuclei as a genetic partner?. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2005, 22, 89–93 10.1007/s10815‐005‐1498‐0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sotolongo B, Lino E, Ward WS. Ability of hamster spermatozoa to digest their own DNA. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69, 2029–2035 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sotolongo B, Huang TT, Isenberger E, Ward WS. An endogenous nuclease in hamster, mouse, and human spermatozoa cleaves DNA into loop‐sized fragments. J Androl, 2005, 26, 272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tateno H, Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Sonication per se is not as deleterious to sperm chromosomes as previously inferred. Biol Reprod, 2000, 63, 341–346 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R, Kuretake S, Bortkiewicz H, Perry AC, Yanagimachi H. Analysis of mouse oocyte activation suggests the involvement of sperm perinuclear material. Biol Reprod, 1998, 58, 1407–1415 10.1095/biolreprod58.6.1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu QC, Chen TE, Huang XY, Sun FZ. Mammalian freeze‐dried sperm can maintain their calcium oscillation‐inducing ability when microinjected into mouse eggs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005, 328, 824–830 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaneko T, Whittingham DG, Overstreet JW, Yanagimachi R. Tolerance of the mouse sperm nuclei to freeze‐drying depends on their disulfide status. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69, 1859–1862 10.1095/biolreprod.103.019729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaneko T, Whittingham DG, Yanagimachi R. Effect of pH value of freeze‐drying solution on the chromosome integrity and developmental ability of mouse spermatozoa. Biol Reprod, 2003, 68, 136–139 10.1095/biolreprod.102.008706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Björndahl L, Kvist U. Sequence of ejaculation affects the spermatozoon as a carrier and its message. Reprod Biomed Online, 2003, 7, 440–448 10.1016/S1472‐6483(10)61888‐3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Björndahl L, Kvist U. Human sperm chromatin stabilization: a proposed model including zinc bridges. Mol Hum Reprod, 2010, 16, 23–29 10.1093/molehr/gap099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ono T, Mizutani E, Li C, Wakayama T. Nuclear transfer preserves the nuclear genome of freeze‐dried mouse cells. J Reprod Dev, 2008, 54, 486–491 10.1262/jrd.20112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chatot CL, Ziomek A, Bavister BD, Lewis JL, Torres I. An improved culture medium supports development of random‐bred 1‐cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil, 1989, 86, 679–688 10.1530/jrf.0.0860679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chatot CL, Lewis JL, Torres I, Ziomek CA. Development of 1‐cell embryos from different strains of mice in CZB medium. Biol Reprod, 1990, 42, 432–440 10.1095/biolreprod42.3.432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bignold LP. Mechanisms of clastogen‐induced chromosomal aberrations: a critical review and description of a model based on failures of tethering of DNA strand ends to strand‐breaking enzymes. Mutat Res, 2009, 681, 271–298 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koppen G, Angelis KJ. Repair of X‐ray induced DNA damage measured by the comet assay in roots of Vicia faba . Environ Mol Mutagen, 1998, 32, 281–285 10.1002/(SICI)1098‐2280(1998)32:3<281::AID‐EM11>3.0.CO;2‐R [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Angelis KJ, Dusinska M, Collins AR. Single cell gel electrophoresis: detection of DNA damage at different levels of sensitivity. Electrophoresis, 1999, 20, 2133–2138 10.1002/(SICI)1522‐2683(19990701)20:10<2133::AID‐ELPS2133>3.0.CO;2‐Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Menke M, Chen IP, Angelis KJ, Schubert I. DNA damage and repair in Arabidopsis thaliana as measured by the comet assay after treatment with different classes of genotoxins. Mutat Res, 2001, 493, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res, 1988, 175, 184–191 10.1016/0014‐4827(88)90265‐0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tice RR, Agurell E, Anderson D, Burlinson B, Hartmann A, Kobayashi H et al. Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ Mol Mutagen, 2000, 35, 206–221 10.1002/(SICI)1098‐2280(2000)35:3<206::AID‐EM8>3.0.CO;2‐J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Baumgartner A, Cemeli E, Anderson D. The comet assay in male reproductive toxicology. Cell Biol Toxicol, 2009, 25, 81–98 10.1007/s10565‐007‐9041‐y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ostling O, Johanson KJ. Microelectrophoretic study of radiation‐induced DNA damages in individual mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1984, 123, 291–298 10.1016/0006‐291X(84)90411‐X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Haines GA, Hendry JH, Daniel CP, Morris ID. Germ cell and dose‐dependent DNA damage measured by the comet assay in murine spermatozoa after testicular X‐irradiation. Biol Reprod, 2002, 67, 854–861 10.1095/biolreprod.102.004382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kamiguchi Y, Tateno H, Iizawa Y, Mikamo K. Chromosome analysis of human spermatozoa exposed to antineoplastic agents in vitro. Mutat Res, 1995, 326, 185–192 10.1016/0027‐5107(94)00168‐5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Karabinus DS, Vogler CJ, Saacke RG, Evenson DP. Chromatin structural changes in sperm after scrotal insulation of Holstein bulls. J Androl, 1997, 18, 549–555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sailer BL, Sarkar LJ, Bjordahl JA, Jost LK, Evenson DP. Effects of heat stress on mouse testicular cells and sperm chromatin structure. J Androl, 1997, 18, 294–301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Haaf T, Schmit M. Experimental condensation inhibition in constitutive and facultative heterochromatin of mammalian chromosomes. Cytogenet Cell Genet, 2000, 91, 113–123 10.1159/000056830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kawase Y, Araya H, Kamada N, Jishage K, Suzuki H. Possibility of long‐term preservation of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa. Biol Reprod, 2005, 72, 568–573 10.1095/biolreprod.104.035279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ward MA, Kaneko T, Kusakabe H, Biggers JD, Whittingham DG, Yanagimachi R. Long‐term preservation of mouse spermatozoa after freeze‐drying and freezing without cryoprotection. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69, 2100–2108 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kaneko T, Nakagata N. Relation between storage temperature and fertilizing ability of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa. Comp Med, 2005, 55, 140–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Toyoda Y, Yokoyama M, Hosi T. Studies on the fertilization of mouse eggs in vitro: 1. In vitro fertilization of eggs by fresh epididymal sperm. Jpn J Anim Reprod, 1971, 16, 147–151 [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sato M, Ishikawa A, Nagashima A, Watanabe T, Tada N, Kimura M. Prolonged survival of mouse epididymal spermatozoa stored at room temperature. Genesis, 2001, 31, 147–155 10.1002/gene.10011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Thuan N, Wakayama S, Kishigami S, Wakayama T. New preservation method for mouse spermatozoa without freezing. Biol Reprod, 2005, 72, 444–450 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Erbach GT, Lawitts JA, Papaioannou VE, Biggers JD. Differential growth of the mouse preimplantation embryo in chemically defined media. Biol Reprod, 1994, 50, 1027–1033 10.1095/biolreprod50.5.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ono T, Mizutani E, Li C, Wakayama T. Preservation of sperm within the mouse cauda epididymidis in salt or sugars at room temperature. Zygote, 2010, 18, 245–256 10.1017/S096719940999027X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kusakabe H, Kamiguchi Y. Ability to activate oocytes and chromosome integrity of mouse spermatozoa preserved in EGTA Tris‐HCl buffered solution supplemented with antioxidants. Theriogenology, 2004, 62, 897–905 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Perry AC, Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. A novel trans‐complementation assay suggests full mammalian oocyte activation is coordinately initiated by multiple, submembrane sperm components. Biol Reprod, 1999, 60, 747–755 10.1095/biolreprod60.3.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Morozumi K, Tateno H, Yanagida K, Katayose H, Kamiguchi Y, Sato A. Chromosomal analysis of mouse spermatozoa following physical and chemical treatments that are effective in inactivating HIV. Zygote, 2004, 12, 339–344 10.1017/S0967199404002989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Saunders CM, Larman MG, Parrington J, Cox LJ, Royse J, Blayney LM et al. PLC zeta: a sperm‐specific trigger of Ca(2+) oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development, 2002, 129, 3533–3544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Cox LJ, Larman MG, Saunders CM, Hashimoto K, Swann K, Lai FA. Sperm phospholipase C zeta from humans and cynomolgus monkeys triggers Ca2+ oscillations, activation and development of mouse oocytes. Reproduction, 2002, 124, 611–623 10.1530/rep.0.1240611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fujimoto S, Yoshida N, Fukui T, Amanai M, Isobe T, Itagaki C et al. Mammalian phospholipase C zeta induces oocyte activation from the sperm perinuclear matrix. Dev Biol, 2004, 274, 370–383 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kusakabe H, Kamiguchi Y. Chromosomal integrity of freeze‐dried mouse spermatozoa after 137Cs gamma‐ray irradiation. Mutat Res, 2004, 556, 163–168 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Rudak E, Jacobs PA, Yanagimachi R. Direct analysis of the chromosome constitution of human spermatozoa. Nature, 1978, 274, 911–913 10.1038/274911a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Araki Y, Yoshizawa M, Araki Y. A novel method for chromosome analysis of human sperm using enucleated mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod, 2005, 20, 1244–1247 10.1093/humrep/deh757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Martin RH. Comparison of chromosomal abnormalities in hamster egg and human sperm pronuclei. Biol Reprod, 1984, 31, 819–825 10.1095/biolreprod31.4.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Brandriff B, Gordon L, Ashworth L, Watchmaker G, Carrano A, Wyrobek A. Chromosomal abnormalities in human sperm: comparisons among four healthy men. Hum Genet, 1984, 66, 193–201 10.1007/BF00286600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Brandriff B, Gordon L, Ashworth L, Watchmaker G, Moore D 2nd, Wyrobek AJ et al. Chromosomes of human sperm: variability among normal individuals. Hum Genet, 1985, 70, 18–24 10.1007/BF00389451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kamiguchi Y, Mikamo K. An improved, efficient method for analyzing human sperm chromosomes using zona‐free hamster ova. Am J Hum Genet, 1986, 38, 724–740 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lee JD, Kamiguchi Y, Yanagimachi R. Analysis of chromosome constitution of human spermatozoa with normal and aberrant head morphologies after injection into mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod, 1996, 11, 1942–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rybouchkin A, Dozortsev D, Pelinck MJ, Sutter P, Dhont M. Analysis of the oocyte activating capacity and chromosomal complement of round‐headed human spermatozoa by their injection into mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod, 1996, 11, 2170–2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Tsuchiya K, Kamiguchi Y, Sengoku K, Ishikawa M. A cytogenetic study of in vitro matured murine oocytes after ICSI by human sperm. Hum Reprod, 2002, 17, 420–425 10.1093/humrep/17.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Watanabe S. A detailed cytogenetic analysis of large numbers of fresh and frozen‐thawed human sperm after ICSI into mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod, 2003, 18, 1150–1157 10.1093/humrep/deg224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Templado C, Donate A, Giraldo J, Bosch M, Estop A. Advanced age increases chromosome structural abnormalities in human spermatozoa. Eur J Hum Genet, 2011, 19, 145–151 10.1038/ejhg.2010.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bedford JM, Bent MJ, Calvin H. Variations in the structural character and stability of the nuclear chromatin in morphologically normal human spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil, 1973, 33, 19–29 10.1530/jrf.0.0330019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Berkovitz A, Eltes F, Ellenbogen A, Peer S, Feldberg D, Bartoov B. Does the presence of nuclear vacuoles in human sperm selected for ICSI affect pregnancy outcome?. Hum Reprod, 2006, 21, 1787–1790 10.1093/humrep/del049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Perdrix A, Travers A, Chelli MH, Scalier D, Do Rego JL, Milazzo JP, Mousset‐Siméon N, Macé B, Rives N. Assessment of acrosome and nuclear abnormalities in human spermatozoa with large vacuoles. Hum Reprod, 2011, 26, 47–58 10.1093/humrep/deq297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wilding M, Coppola G, di Matteo L, Palagiano A, Fusco E, Dale B. Intracytoplasmic injection of morphologically selected spermatozoa (IMSI) improves outcome after assisted reproduction by deselecting physiologically poor quality spermatozoa. J Assist Reprod Genet, 2011, 28, 253–262 10.1007/s10815‐010‐9505‐5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Figueira Rde C, Braga DP, Setti AS, Iaconelli A Jr, Borges E Jr. Morphological nuclear integrity of sperm cells is associated with preimplantation genetic aneuploidy screening cycle outcomes. Fertil Steril, 2011, 95, 990–993 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mauri AL, Petersen CG, Oliveira JB, Massaro FC, Baruffi RL, Franco JG Jr. Comparison of day 2 embryo quality after conventional ICSI versus intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection (IMSI) using sibling oocytes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2010, 150, 42–46 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Watanabe S, Tanaka A, Fujii S, Mizunuma H, Fukui A, Fukuhara R et al. An investigation of the potential effect of vacuoles in human sperm on DNA damage using a chromosome assay and the TUNEL assay. Hum Reprod, 2011, 26, 978–986 10.1093/humrep/der047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]