Abstract

Background

Ag2S has the characteristics of conventional quantum dot such as broad excitation spectrum, narrow emission spectrum, long fluorescence lifetime, strong anti-bleaching ability, and other optical properties. Moreover, since its fluorescence emission is located in the NIR-II region, has stronger penetrating ability for tissue. Ag2S quantum dot has strong absorption during the visible and NIR regions, it has good photothermal and photoacoustic response under certain wavelength excitation.

Results

200 nm aqueous probe Ag2S@DSPE-PEG2000-FA (Ag2S@DP-FA) with good dispersibility and stability was prepared by coating hydrophobic Ag2S with the mixture of folic acid (FA) modified DSPE-PEG2000 (DP) and other polymers, it was found the probe had good fluorescent, photoacoustic and photothermal responses, and a low cell cytotoxicity at 50 μg/mL Ag concentration. Blood biochemical analysis, liver enzyme and tissue histopathological test showed that no significant influence was observed on blood and organs within 15 days after injection of the probe. In vivo and in vitro fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging of the probe further demonstrated that the Ag2S@DP-FA probe had good active targeting ability for tumor. In vivo and in vitro photothermal therapy experiments confirmed that the probe also had good ability of killing tumor by photothermal.

Conclusions

Ag2S@DP-FA was a safe, integrated diagnosis and treatment probe with multi-mode imaging, photothermal therapy and active targeting ability, which had a great application prospect in the early diagnosis and treatment of tumor.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12951-018-0367-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ag2S, Cancer active targeting, Fluorescence imaging, Photoacoustic imaging, Photothermal therapy

Background

Early diagnosis of cancer can greatly improve the survival of patients [1]. More and more imaging methods have been applied to diagnose tumor, such as electronic computed tomography (CT), photoacoustic imaging (PAI), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission computed tomography (PET), fluorescence imaging (FI) and so on.

As a molecular imaging technique, FI has the advantages of high resolution and low acquisition time, it can observe the dynamic change of tumor-related molecules in real time, so it has great application prospect in early diagnosis [2–4]. However, some endogenous substances (hemoglobin, water, bilirubin and melanin, etc.) in biological tissues have strong absorption and scattering for visible light (400–700 nm) [5], which result in the limited penetration of photon. By contrast, near-infrared (NIR) light has stronger penetrating ability because of weak tissue scattering and absorption in that region, so NIR fluorescent materials usually are used as probe for in vivo imaging [6]. Ag2S is a new type of low-toxic quantum dot reported in recent years. It has the characteristics of conventional quantum dot such as broad excitation spectrum, narrow emission spectrum, long fluorescence lifetime, strong anti-bleaching ability, and other optical properties [7]. Moreover, since its fluorescence emission is located in the NIR-II region, it has stronger penetrating ability for tissue and can also eliminate the interference of biological spontaneous fluorescence, which contributes to the improvement of signal-to-noise ratio [8]. So it is a promising quantum dot for in vivo imaging.

PAI is a new kind of molecular imaging technology developed in recent years [9]. In PAI, a short pulsed laser beam is used to illuminate the biological tissue. The absorption of laser pulse energy of the tissue then induces an instantaneous temperature rise and transient thermoelastic expansion, leading to ultrasonic emissions (photoacoustic waves). Researchers can map the light absorption distribution in the tissues by measuring the photoacoustic (PA) signals [10]. PAI combines the advantages of high-contrast of optical imaging and high penetration depth of ultrasound imaging, avoids the effect of light scattering in principle, can achieve the deep tissue imaging similar to ultrasound imaging and high-contrast imaging similar to optical coherence tomography, demonstrates broad prospect for early diagnosis and efficacy monitoring [11, 12]. Ag2S quantum dot has strong absorption during the visible and NIR regions [13], it has good photoacoustic response under certain wavelength excitation, so it is also a good PAI contrast agent.

Single imaging model often cannot provide comprehensive information due to the existence of certain defects. Combining two or more imaging technologies is an inevitable trend in the development of in vivo molecular imaging technology, which is also an effective way to early diagnose and treat cancer. So multi-modal imaging technology comes into being [14–16]. FI can give the three-dimensional quantitative results of fluorescence molecules in vivo, but there are some shortcomings in obtaining structural information; PAI can provide high-resolution and high-contrast tissue imaging. Therefore, combining FI and PAI is an ideal dual-mode molecular imaging method [17]. FI provides the distribution and location of trace cancer-related molecules in tissues, while PAI provides deep tissue and spatial structure information.

Thermotherapy as an effective treatment for cancer has aroused widespread attention [18–21]. Tumor thermotherapy uses the physical energy to heat, make the tumor temperature rise to the effective treatment temperature (> 41 °C) [22] and maintain a certain time. Due to different temperature tolerance comparing with normal cell, tumor cell apoptosis is achieved without damaging the normal cell. Photothermal therapy (PTT) research in the past is mainly using NIR organic dyes [23]. In recent years, studies have shown that absorption cross sections of some metal nanoparticles are 4–5 times larger than the conventional dyes [24], and have better stability and stronger anti-photobleaching, so they become the ideal choice for PTT. It is gratifying that, Ag2S quantum dot had significant photothermal effect reported by Wu et al. in 2016 [25]. It is thought that Ag2S quantum dot can achieve NIR fluorescence and photoacoustic dual-mode imaging, meanwhile be used to kill the tumor through photothermal [26], it achieves the purpose of diagnosis and treatment integration perfectly.

In this paper, a multi-functional folic acid (FA) modified phospholipid coating Ag2S probe (Ag2S@DSPE-PEG2000-FA) with low biotoxicity was prepared by mixing lecithin, polyoxyethylene stearate, DSPE-PEG2000 (DP) and FA modified DP (DP-FA). The design idea is that DP is a very safe amphiphilic molecule whose hydrophilic end can improve the water solubility of the nanoprobe and help the probe to escape the phagocytosis of the reticuloendothelial system and prolong the cycle time in the body [27]. However, due to its limited emulsifying ability, lecithin and polyoxyethylene stearate are required to assist. These two materials can be effectively utilized by the body and have little hemolysis effect, are safe and reliable injection emulsion surfactant. FA, as a small molecule of vitamin, can bind FA receptors which are highly expressed on the surface of some tumor cells to guide the endocytosis, while it is easily coupled with nanoparticles, free of immunogenicity and low cost. Two kinds of cells were adopted, while HeLa cells (high FA receptor expression) [28] as positive cell and A549 cells (low FA receptor expression) [29] as negative cell; two kinds of probes were also adopted, while Ag2S@DP-FA as positive probe and Ag2S@DP as negative probe. Cross-contrast experiments were performed by fluorescence, photoacoustic and photothermal, the results confirmed that Ag2S@DP-FA probe was an integrated diagnosis and treatment probe with good safety, it had abilities of fluorescence and photoacoustic dual-mode imaging, PTT and active targeting function, had large application prospect in the early diagnosis and treatment of tumor.

Methods

Materials and instrument

Diethyldithiocarbamic acid silver salt (AgDDTC, 98%), dodecanethiol (DT, 98%), n-hexane, acetone, trichloromethane, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), folic acid (FA, 97%) and pyridine were purchased from Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. PEG-phospholipid (DSPE-PEG2000), amino-PEG-phospholipid (DSPE-PEG2000-NH2) were purchased from Avanti, lecithin (98%), polyoxyethylene stearate were purchased from Aladdin, octadecene (ODE, 90%) was purchased from Aldrich. All reagents were used directly without further purification.

The equipments used in the experiments included UV-2550 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan), Tecnai G20 U-Twin High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscope (FEI, Netherlands), Nano-ZS90 Nanometer Size Meter (Malvern, UK), Ni-E Positive Slice Scanning Microscope (Nikon, Japan), SP-4430 Dry Biochemical Analyzer (Arkary, Japan), Centrifugal Concentrator (Ependorf, Germany), Elx-808 Microplate Reader (Biotek, USA), CA-700 Automatic Blood Analyzer (STAC, China), MDL-III-808-2.5 W Laser (Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Tech. CO., LTD., China), EasIR-9 Thermal Imager (Wuhan Guide Infrared Co., LTD, China), IX71 Fluorescence Microscope (Olympus, Japan). Near infrared FI system [30] and PAI system [31, 32] were homemade by the laboratory.

Synthesis of hydrophobic Ag2S

The synthesis of Ag2S was according to the reported method [33, 34] with slightly modified. 76.8 mg AgDDTC, 30 g ODE and 6 g DT were added into a 100 mL four-necked flask and vigorously stirred with passing through Ar, heated to 100 °C and kept for 5 min to remove the water then raised the temperature to 160 °C, after the solution color was completely dark, kept for 10 min and cooled down to room temperature, after centrifugal purification for 12,000 r/min by adding acetone, the resulting Ag2S was dissolved in chloroform and stored at 4 °C. Different concentrations of Ag2S were placed in centrifuge tubes and imaged by homemade NIR fluorescence imaging system.

The concentration of Ag in Ag2S was used to indicate the concentration of probe. A certain amount of Ag2S was taken out at room temperature, after the chloroform completely evaporated, HNO3 was added to dissolve it, titrated with NH4SCN (ferric ammonium alum as indicator), when the solution turned red, the titration end point was reached, then the concentration could be calculated.

Synthesis of Ag2S@DSPE-PEG2000-FA (Ag2S@DP-FA)

According to the literature [35], 2 mL DMSO, 1 mL pyridine, 10 mg folic acid, 13 mg dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DDC) and 4 mg DSPE-PEG2000-NH2 (DP-NH2) were joined in a 10 mL round bottom flask, stirred for 4 h in dark environment. The pyridine was removed by suspension, the remaining solution was dialyzed twice in 4.2 g/L NaHCO3 solution and three times in deionized water to remove free folic acid. Finally, the solution in dialysis bag was lyophilized to obtain DP-FA and stored in − 20 °C.

Ag2S@DP-FA was attached as positive probe. 4 mg lecithin, 6 mg polyoxyethylene stearate, 2 mg DP, 1 mg DP-FA and 700 μL Ag2S joined in a 10 mL round bottom flask, mixed at room temperature and slowly evaporated to dry, after that, added a small amount of PBS to dissolve. The method of synthesis phospholipid coating Ag2S negative probe without FA (Ag2S@DP) was consistent with the positive probe except adding DP-FA.

The probe’s stability was characterized by measuring the size and Zeta potential of Ag2S@DP-FA under 4, 25 and 37 °C respectively at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 days.

PAI and PTT evaluation of Ag2S@DP-FA

Different concentration Ag2S@DP-FA probes (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1 mg/mL) embedded in 1% agar gel cylinders were performed quantitatively using single ELISA plate. The photoacoustic image (PAI) was measured at 744 nm and 0.6 mJ using a homemade PA system.

200 µL aqueous suspensions containing different concentrations of Ag2S@DP-FA probes were poured into different ELISA plates, and then illuminated by 808 nm laser with tunable output power density for 5 min. The increase of temperature was monitored and recorded by Thermal Camera.

Cytotoxicity of the Ag2S@DP-FA

HeLa and A549 cells were homogenously inoculated in a 96-well plate for 8 groups, 5 repeated experiments for each group. Ag2S@DP-FA at concentrations of 0, 3.2, 6.4, 13, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL were added to the cells. After incubating for 24 h, 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and kept for 4 h, the medium was sucked out and 150 μL DMSO was added to dissolved the violet crystals. The 96-well plate was shaken for 15 min, finally the absorbance was measured at 490 nm.

Long-term cytotoxicity of Ag2S@DP-FA was determined by clone formation assay [36]. According to the MTT method, the cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated with different concentration Ag2S@DP-FA (0, 3.2, 6.5, 13, 25, and 50 mg/mL), besides, 4 parallels were set for each concentration. After 24 h incubation, about 2000 cells were inoculated in 6-well plates at each concentration. After 7 days culture, they were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 min, washed the glutaraldehyde with PBS and added 5% crystal violet staining for 15 min. Finally, the number of cell communities was counted by Photoshop.

In vitro FI and PAI

The positive HeLa cells and negative A549 cells were incubated with 50 µg/mL Ag2S@DP-FA and Ag2S@DP, respectively. After 12 h, the culture medium was aspirated and washed several times with PBS to ensure no free probe was presented. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and imaged by the homemade NIR fluorescence imaging system.

HeLa cells were divided into four groups, treated by Ag2S@DP-FA, Ag2S@DP, 1 mg FA for 1 h before Ag2S@DP-FA, and blank buffer respectively. After 2 h, the cells were washed by PBS for three times to clean up the uncombined probes. Then the cells were harvested by 0.25% trypsin–EDTA solution, and collected in 1% agar gel cylinders with single ELISA plates after centrifuging at 1000 rpm for 8 min and washing for three times with PBS. The PA signals were measured by the homemade PAI system.

In vitro PTT

Positive and negative cells were seeded in a 24-well plate for 24 h prior to treatment respectively. 0.5 mL positive and negative probes dispersed in culture medium at the same Ag concentration of 25 μg/mL were added into the wells and incubated respectively. After 2 h, the cells were washed by PBS for three times to clean up the uncombined probes. Then the cells were irradiated for 5 min using 808 nm laser with a power density of 1.8 W/cm2. After that, the cells were stained by calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM) for 5 min, and observed by inverted optical fluorescence microscope.

TEM of cell uptake probes

Similar to fluorescence test, after incubation, HeLa and A549 cells were immobilized with 1% OsO4, then treated with different concentration ethanol (50, 70, 80, 85, 90, 95 and 100%), resined 48 h in the Epon812 at 60 °C. Ultra-thin slides were cut and observed by TEM.

In vivo toxicity of the probe

50 BALB/c mice (male, SPF, 4 weeks) were divided into 5 groups randomly, half mice of each group were injected with Ag2S@DP probe (108 mg Ag/kg) by tail vein and the others were injected with the same volume of PBS. 300 μL blood was obtained at 0, 6 h, 1, 3, 7 and 15 days, 200 μL for liver enzyme analysis, AST and ALT, other 100 μL for blood analysis, RBC, WBC, PLT, and HGB. At the same time, the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and small intestine were collected, fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded, sliced and HE staining, placed under the optical microscope for histopathological examination. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

In vivo targeting FI, PAI and PTT

Several BALB/c nude mice (male, SPF, 4 weeks) were randomly divided into 4 groups, group I and II were inoculated with positive HeLa cells, group III and IV were seeded with negative A549 cells. The dimensions of the tumors were monitored by vernier caliper every 2 days. Once the tumor volume grew to 80 mm3, Ag2S@DP-FA positive probe (108 mg Ag/kg) was injected into group I and III by tail vein, group II and IV were injected with the same amount of Ag2S@DP negative probe. The mice were imaged with the NIR fluorescence imaging system at 0 h, 5 min, 1, 2, 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. At the same time point, the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, small intestine and tumor of some mice in group I were collected and imaged by the homemade NIR fluorescence imaging system.

Twenty HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into 4 groups for PTT. Group I was exposed to NIR laser with an output power density of 2.8 W/cm2 for 10 min after tail intravenously injection of Ag2S@DP-FA (108 mg Ag/kg); group II was irradiated for 10 min with injection of 600 μL saline solution; group III was tail intravenously injected with Ag2S@DP-FA (108 mg Ag/kg) without NIR laser irradiation; group IV was as a blank control without any treatment. Same as group I, positive probe was injected to another batch of tumor-bearing nude mice, in vivo photoacoustic imaging experiment was carried out at different time points. In the experiment, the nude mice were fixed on the stage of the photoacoustic system after anesthesia with 10 μL/g of urethane. The wavelength of laser was 744 or 532 nm and the laser energy per pulse was 200 nJ.

Results and discussion

The NIR-II region emission of Ag2S quantum dot can greatly reduce the interference of spontaneous fluorescence from the organism, improve the signal to noise ratio. In addition, the absorption and scattering of light in the NIR-II region are less, so Ag2S has a stronger penetrating ability comparing with the traditional quantum dot, which can be used for the in vivo non-invasive imaging.

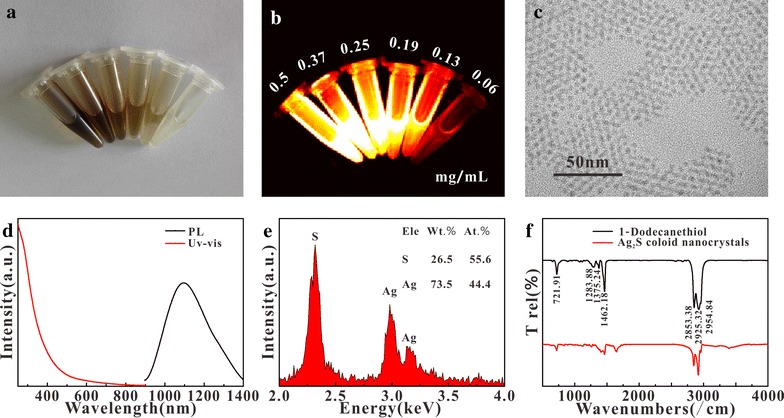

As the first step of this study, the hydrophobic Ag2S nanoparticle was synthesized (Fig. 1a), its fluorescence intensity increased significantly accompanying with increasing concentration (Fig. 1b). The spectral characterization showed a wide absorption and ~ 1100 nm emission (Fig. 1d). TEM showed that Ag2S had a relatively uniform size about 5 nm (Fig. 1c). EDS test showed that the sample consisted of Ag and S elements, but the molar ratio was less than 2:1 (Fig. 1e), this might be due to the fact that dodecanethiol (DT) contained S, increased the relative content of sulfur. The surface ligand on Ag2S was detected by infrared spectroscopy, results showed that Ag2S had a consistent characteristic of infrared spectroscopy with DT (Fig. 1f), indicating that DT had been successfully attached to the Ag2S surface.

Fig. 1.

White light (a) and fluorescence (b) image, TEM (c), absorption and emission spectra (d), EDS (e) of Ag2S; the infrared spectrum of Ag2S and DT (f)

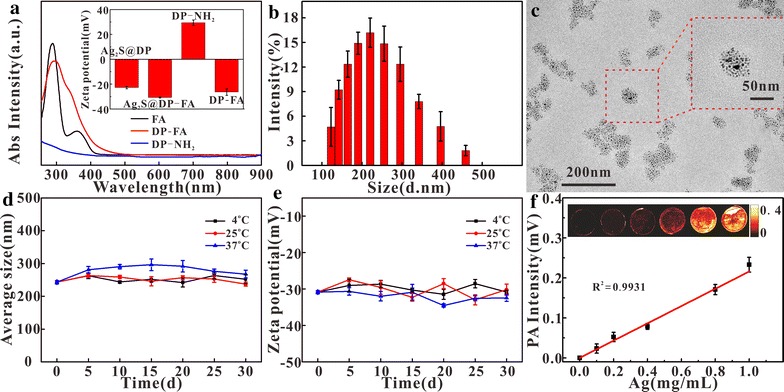

The target molecule FA was attached to DP-NH2 by DDC. To confirm whether or not FA had been successfully connected with DP-NH2, the absorption spectra of FA, DP-NH2, and DP-FA were measured (Fig. 2a). The results showed that the peak of FA was at 280 nm, while DP-FA had an obvious absorption at 280 nm comparing with the DP-NH2. In addition, the Zeta potential of these materials were also measured (Fig. 2a, insert). DP-NH2 was + 29.4 mV because it had amino group; for DP-FA, the FA possessed two carboxyl groups, even if one of them was linked with DP-NH2, the other carboxyl group also led to negative charge at − 26.4 mV. After modifying Ag2S particles, it was found that a higher negative potential (− 30.84 mV) was obtained than DP-modified particles without FA (− 21.8 mV). All these results confirmed that FA had been successfully conjugated with DP-NH2.

Fig. 2.

Absorption spectra of FA, DP-FA and DP-NH2 (a), insert: Zeta potentials of DP-NH2, DP-FA, Ag2S@DP-FA and Ag2S@DP (n = 5); dynamic light scattering results (b) (n = 5) and TEM (c) of Ag2S@DP-FA; the change of particle size (d) and Zeta potential (e) of Ag2S@DP-FA at different temperatures (n = 5); the PA response of the different concentrations of the probe (f) (n = 5), insert: PAI of probe

The size of Ag2S@DP-FA was about 200 nm measured by dynamic light scattering method (Fig. 2b). TEM showed a size of about 50 nm (Fig. 2c). This phenomenon might be due to the fact that the former was the hydrated size [37]. The stability of Ag2S@DP-FA was also measured (Fig. 2d, e). The results showed that the size and potential of Ag2S@DP-FA had no obvious change at different temperatures within 30 days, indicating a good stability.

Ag2S@DP-FA had strong absorption during the visible and NIR region. There were good PA response and PTT effect under certain wavelength laser irradiation. The in vitro photoacoustic and photothermal experiments of probe were carried out. Results showed it had obvious PA response under 744 nm laser irradiation. It could be seen that accompanying with the increasing Ag concentration, PA signal generated by Ag2S@DP-FA was strengthened (Fig. 2f) with a great linear relationship (R2 = 0.9931), indicating good ability of PAI.

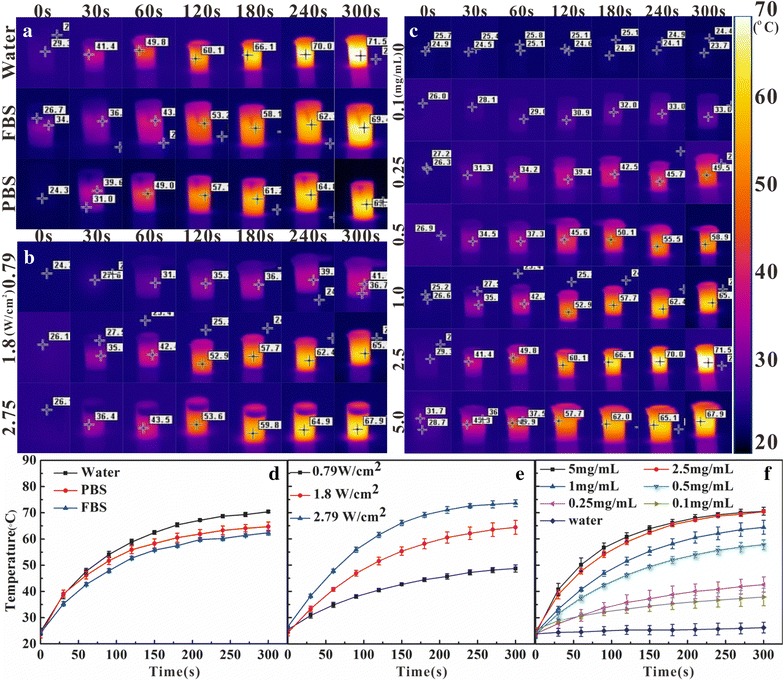

It was found that Ag2S@DP-FA (2.5 mg/mL) dispersed in deionized water, PBS and fetal bovine serum (FBS) all showed perfect photothermal conversion under NIR laser irradiation (Fig. 3a, d). And when the power density of NIR laser was increased, the temperature of aqueous dispersion of Ag2S@DP-FA (1.0 mg/mL) also increased (Fig. 3b, e). Furthermore, when Ag2S@DP-FA concentration increased, temperature of the aqueous dispersion could be elevated up to higher temperature (Fig. 3c, f). However, the temperature increment with the increase of concentration was not obvious when the concentration was above 2.5 mg/mL. Comparatively, the control experiment of deionized water showed the temperature increment less than 1 °C under the same experimental conditions. These results indicated that Ag2S probe had excellent photothermal conversion capability.

Fig. 3.

The picture of temperature evolution of 2.5 mg/mL Ag2S@DP-FA in different solvent under 1.8 W/cm2 laser over time (a); 1.0 mg/mL Ag2S@DP-FA in water under different laser power densities (b); different concentration Ag2S@DP-FA in water under 1.8 W/cm2 laser (c); d–f were the temperature evolution curves over time corresponding to (a, b, c), respectively (n = 5)

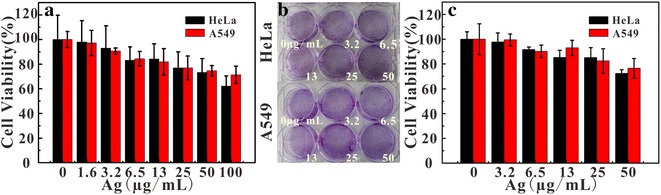

The toxicity of the probe was the key for application. The cytotoxicity of Ag2S@DP-FA probe was investigated by MTT assay. HeLa and A549 cells were incubated for 24 h with different concentration probe (Ag: 0, 1.6, 3.2, 6.5, 13, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL). Succinate dehydrogenase in the mitochondria of living cells could reduce MTT to blue-violet crystals that could deposit in cells, whereas dead cells had no this function [38]. Results showed that when the concentration of Ag was up to 50 μg/mL, the cells still had near 80% survival (Fig. 4). Long-term cytotoxicity experiment was investigated by the colony formation assay. Cell viability was estimated through the number of cell population (Fig. 4b). It was found the results (Fig. 4c) were consistent with the MTT results, indicating that Ag2S @ DP-FA probe had a lower cytotoxicity.

Fig. 4.

MTT test of Ag2S@DP-FA (a) (n = 5); white light results (b) and cell community data statistics (c) (n = 5) of colony formation assay method to detect the long-term toxicity of the probe

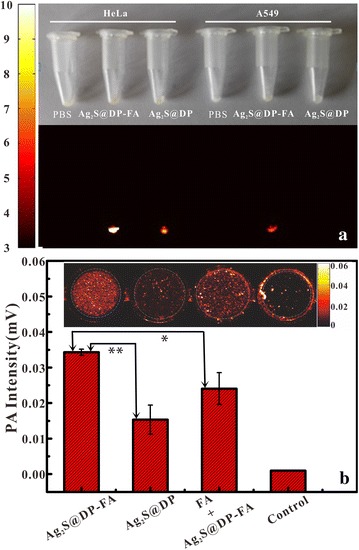

Then the active target ability of the probe was examined. HeLa and A549 cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL Ag2S@DP-FA and Ag2S@DP. The results showed that HeLa cells incubated with Ag2S@DP-FA were turned yellow and had the strongest fluorescence (Fig. 5a); while A549 cells incubated with Ag2S@DP-FA and HeLa cells incubated with Ag2S@DP were only observed faint yellow, and the fluorescence of the two was weak; the other groups looked white and no fluorescence was observed. The above results showed that Ag2S@DP-FA could specifically bind to FA receptors which high expressed on HeLa cells, and had no effective targeting ability for A549 cells which low expressed FA receptor. Likewise, negative probe Ag2S@DP had no effective targeting binding to HeLa and A549 cells. This experiment showed that the Ag2S@DP-FA probe could be used as an active targeting imaging diagnostic reagent for some tumors that high expressed FA receptors such as HeLa, and had the ability for target FI.

Fig. 5.

White light and FI results of different cells incubated with different probes (a) and photoacoustic response results of different probe-labeled positive HeLa cells (b) (n = 5), *meant significant difference (p < 0.05), **meant great significant difference (p < 0.01)

PAI was also conducted at the cellular level. HeLa cells were incubated with different probes for PAI. The results showed that both Ag2S@DP-FA and Ag2S@DP incubating HeLa cells had PA signals (Fig. 5b), indicating negative probe also combined to HeLa cells through nonspecific adsorption, this was consistent with the FI results (Fig. 5a). But there was great significant difference between them (p < 0.01), meant Ag2S@DP-FA combined to HeLa cells more easily than Ag2S@DP. To verify this further, FA was added into the cell culture flask before 1 h of adding Ag2S@DP-FA, significant difference was obtained (p < 0.05). It was because that the FA receptors on the cell surface were combined with free FA firstly, resulting in subsequent Ag2S@DP-FA could not combine to HeLa. These experiments above confirmed that Ag2S@DP-FA had good active target ability.

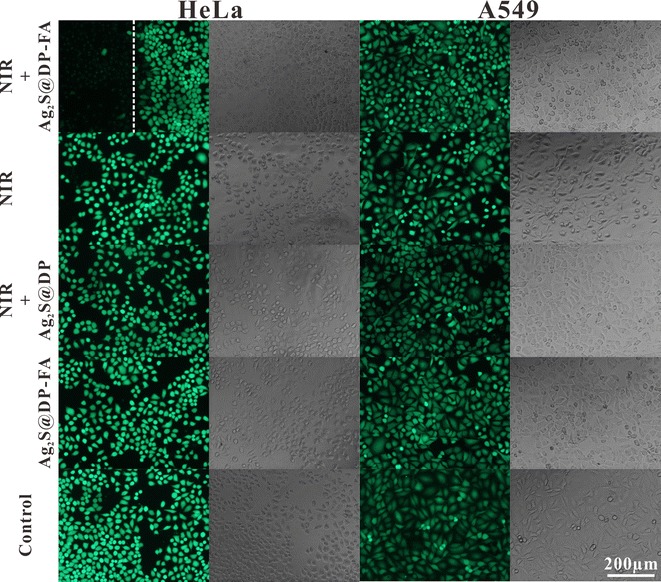

FA as a target molecule on the probe, its targeting could be also verified by the effect of PTT. When Ag2S@DP-FA positive probe was incubated with HeLa cells and irradiated with laser for 5 min, calcein staining revealed that the cells in the non-irradiated region had significant fluorescence, while the irradiated area showed only extremely weak fluorescence (Fig. 6). Calcein is a cell dyeing reagent which could stain live cell producing green emission except dead one [39]. If HeLa cells were only incubated with Ag2S@DP-FA without any irradiation, the cells showed obvious green fluorescence. To rule out the possibility of death by laser, HeLa cells were exposed to laser irradiation directly under same factors, the results showed that the cells still had bright green fluorescence, indicating that cell death was caused by the thermal effect of Ag2S@DP-FA. In order to investigate the ability of active targeting of probe, HeLa cells were incubated with Ag2S@DP, the results showed after laser irradiation the cells still had green fluorescent, meant negative probe could not target HeLa effectively. It seemed opposite to the results of PAI (Fig. 5b), but it was understandable, although there was nonspecific adsorption of Ag2S@DP, not in sufficient quantities to enhance temperature to kill cells, so they were still alive. For control experiments, no matter what kind of conditions above, as low FA receptor expression cell, A549 all present obvious green fluorescence. These experiments proved that only HeLa cells incubated with Ag2S@DP-FA could be killed by laser irradiation, which could fully demonstrate Ag2S@DP-FA had good ability of active targeting and PTT.

Fig. 6.

HeLa and A549 were incubated with positive probe (Ag2S@DP-FA) or negative probe (Ag2S@DP), and then treated with or without NIR laser irradiation. Cells were stained by calcein-AM. Laser power was 1.8 W/cm2, and irradiation time was 5 min. White dotted line was the border of laser irradiation

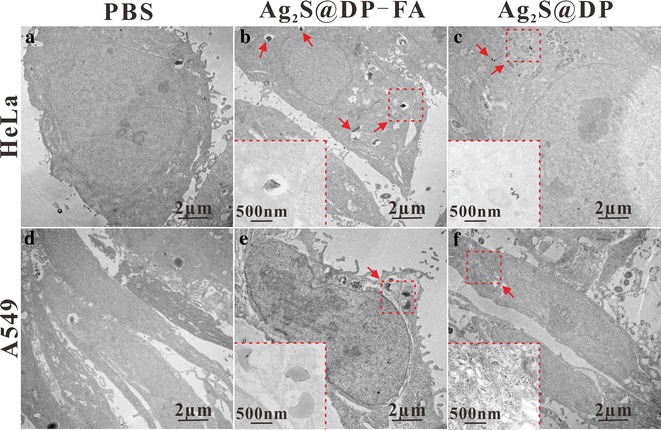

TEM was used to further investigate the uptake of different probes by HeLa cells and A549 cells (Fig. 7). The results showed that comparing with the PBS control group (Fig. 7a, d), black particles appeared in the cytoplasm of HeLa (Fig. 7b) and A549 (Fig. 7e) cells in Ag2S@DP-FA group, which confirmed that both HeLa and A549 cells could ingest a certain amount of Ag2S@DP-FA probes by endocytosis, the amount of probes in HeLa cells was significantly higher than A549 cells. This result was consistent with the results of the FI and PAI because HeLa cells expressed more FA receptors than A549 cells, and thus could bind more targeting probes. There were also a few probes in the HeLa and A549 cytoplasm in Ag2S@DP group, and probes in the HeLa cells (Fig. 7c) were slightly more than A549 cells (Fig. 7f). This was also consistent with the results of FI. Overall, the amount of Ag2S@DP-FA probes in the HeLa cytoplasm was significantly the highest than the other control groups, this was consistent with the FI and PAT and PTT experiments, indicating that the Ag2S@DP-FA probe had a good active targeting ability and could be used as a target imaging diagnostic reagent.

Fig. 7.

TEM of cells incubated with probes. a HeLa + PBS; b HeLa + Ag2S@DP-FA; c HeLa + Ag2S@DP; d A549 + PBS; e A549 + Ag2S@DP-FA; f A549 + Ag2S@DP. Inserts in b, c, e and f were the corresponding local magnification

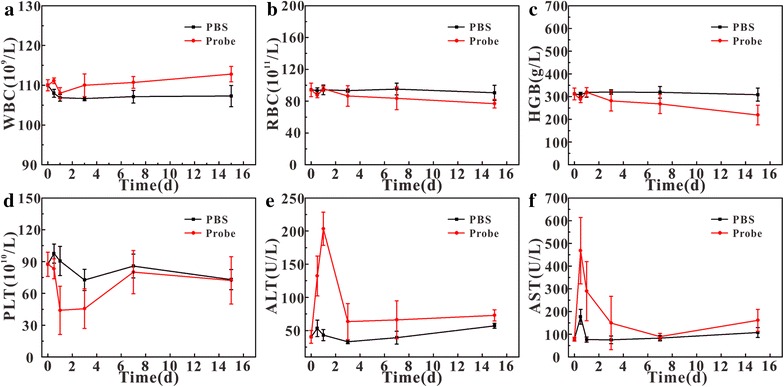

In order to evaluate the in vivo safety of the probe, the blood biochemical indexes in mice were examined after injection of the probe. The results showed that there was no significant difference in white blood cell (WBC) (Fig. 8a), red blood cell (RBC) (Fig. 8b), and hemoglobin (HGB) (Fig. 8c) between the probe group and the PBS control group. The platelet (PLT) in probe group (Fig. 8d) was significantly reduced after 1 day but returned to normal at 7 days, indicating the probe did not cause irreversible damage to the mice. In addition, the effect of probe on liver function was investigated by testing the level of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (Fig. 8e) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 8f). The results showed that ALT and AST contents significantly changed after injection then backed to normal levels at 3 days, PBS group also had similar change. The reason for this short rise was due to the use of anesthetics, which might increase liver enzyme activity and cause AST and ALT in the mice blood to be temporarily rising for several hours [40]. The above results showed that our synthetic probe had good biosafety.

Fig. 8.

Blood sample analysis after injection (n = 5). a WBC; b RBC; c HGB; d PLT; e ALT; f AST

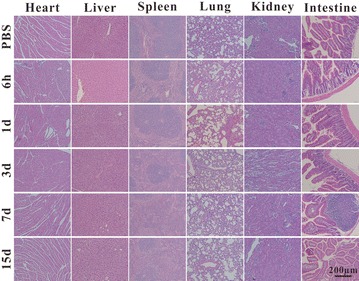

In addition to blood analysis, the effects of probes on mice organs were also examined. Comparing the HE staining results of PBS group with probe group at 6 h, 1, 3, 7 and 15 days after injection (Fig. 9), it was found that the tissue structure of heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and small intestine did not change significantly, indicating that the probe had little effect on these organs, further proved that our probe had good biosecurity.

Fig. 9.

The HE staining results of the main organ after injecting PBS and probe for 6 h, 1, 3, 7, 15 days shown in from top to bottom, from the left to right was heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and intestine

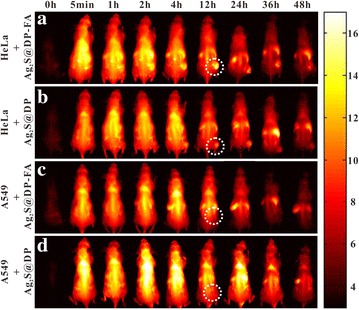

After that, the in vivo active targeting imaging ability of the probe was examined. The Ag2S@DP-FA and Ag2S@DP probes were injected into HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice and A549 tumor-bearing nude mice by tail vein, and they were imaged by homemade NIR fluorescence imaging system at different times. The results showed that Ag2S@DP-FA spread all over HeLa tumor-bearing nude mouse after 5 min, the tumor site had obvious fluorescence after 1 h and showed brightest fluorescence at 12 h, then it began to decay, after 36 h, the tumor site still had a certain intensity of fluorescence (Fig. 10a). While the HeLa tumor-bearing nude mouse injected with Ag2S@DP had a weaker fluorescence in tumor at 4 h, and the fluorescence disappeared at 24 h (Fig. 10b). As for A549 tumor-bearing nude mice, no significant fluorescence enhancement were observed at the tumor sites (Fig. 10c, d), indicating that the probe did not enrich at the tumor sites. This series of in vivo fluorescence imaging were consistent with in vitro FI results, further showed that Ag2S@DP-FA probe had a good active targeting imaging capability.

Fig. 10.

FI of the target tumor in the nude mice at 0 h, 5 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h (the tumor site in the dashed line cycle). a HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice + Ag2S@DP-FA; b HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice + Ag2S@DP; c A549 tumor-bearing nude mice + Ag2S@DP-FA; d A549 tumor-bearing nude mice + Ag2S@DP

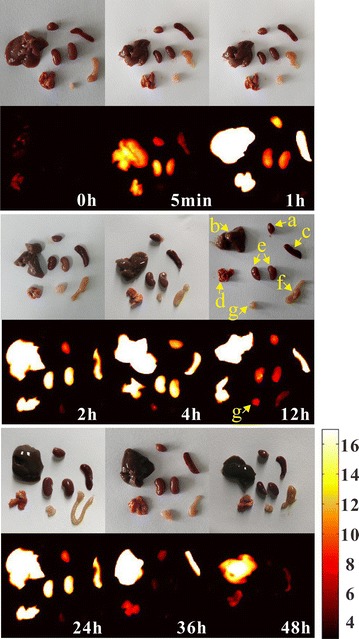

Next, the distribution of the probe in the nude mice was examined. At different times, the main organs and tumor were collected for FI. The results showed that the probe had more residues in the liver, spleen and lungs, and had fewer residues in the heart, kidneys and small intestine (Fig. 11). With the extension of time, the probe gradually discharged from the organs. Tumor site began to light at 1 h, the fluorescence effect was more obvious at 4 h, and reached the maximum at 12 h, then began to weaken and continued to 36 h, same with in vivo targeted FI.

Fig. 11.

White and fluorescence imaging of heart (a), liver (b), spleen (c), lung (d), kidney (e), small intestine (f), and tumor (g) in HeLa tumor-bearing nude mice at 0 h, 5 min, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h after injection of Ag2S@DP-FA

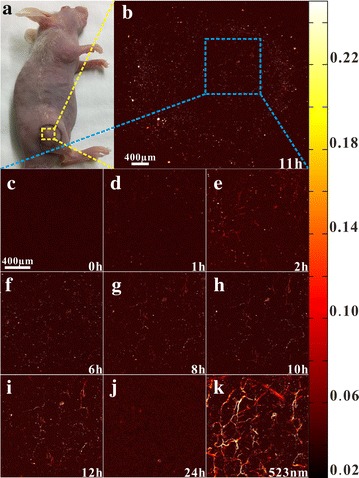

Once the tumor volumes were about 80 mm3, in vivo PAI of nude mice tail intravenously injected with Ag2S@DP-FA was carried out using 744 nm laser. The PAI system has high lateral resolution (~ 4 µm), it showed before tail intravenous injection, there was no PA signal on the tumor (Fig. 12c). After injection, PA signal intensity of tumor showed significant enhancement comparing with the background (Fig. 12b). It indicated that the accumulation of Ag2S@DP-FA into the tumor was increased in the initial several hours, and reached the highest after 12 h, the PA response became weak after 24 h (Fig. 12d–j). This result was consistent with the FI. To determine whether or not the imaging was indeed at a vascular site of the tumor, PA signal of the same tumor region was also detected under 523 nm, it showed that there were rich blood vessels due to strong PA response of hemoglobin at this wavelength (Fig. 12k), the pattern was consistent with the PAI at 12 h (Fig. 12i). It demonstrated PA signal at 744 nm was derived from Ag2S@DP-FA targeted to the tumor.

Fig. 12.

In vivo PAI of the nude mouse tail intravenously injected with Ag2S@DP-FA (a); the whole tumor after injecting 11 h under 744 nm laser excitation (b); the same part of tumor at different times under 744 nm laser excitation (c–j); the same part of tumor under 523 nm laser excitation (k)

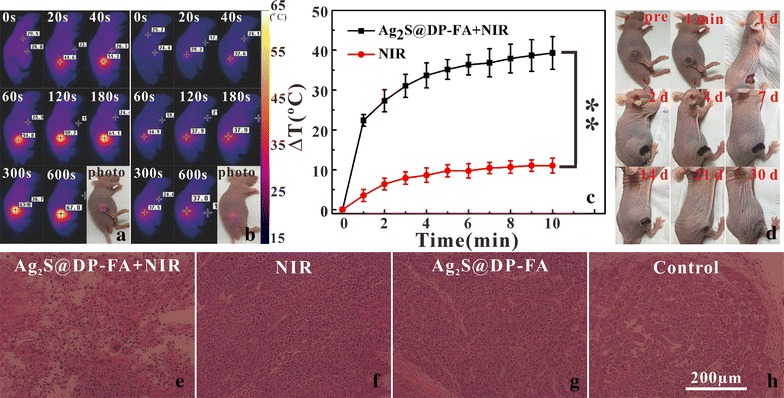

Based on efficient in vitro PTT effect and in vivo FI and PAI, in vivo PTT was carried out further. After undergoing laser irradiation for 10 min, the temperature of bearing tumor on nude mouse tail intravenously injected with Ag2S@DP-FA could rise up to 67 °C (Fig. 13a, c), which would kill the tumor adequately. As control group, the temperature of bearing tumor on nude mouse tail intravenously injected with saline just rose up 10 °C (Fig. 13b, c), there was great significant difference between them (p < 0.01), indicating that the Ag2S@DP-FA probe targeted to the tumor exerted significant PTT effect. The region of tumor treated with Ag2S@DP-FA was charred immediately upon laser irradiation and further became black scar after 1 day, as time went on, the scar of tumor was healed little by little, and became remarkable recovery finally (Fig. 13d), suggesting the cancer was killed by high temperature. Actually, the group injected with Ag2S@DP-FA and underwent laser irradiation was completely cured without reoccurrence after 60 days investigation. H&E stain of tumor tissue was further conducted to reveal the therapeutic mechanism. It was found that apparent extensive necrosis appeared in the group treated with Ag2S@DP-FA and laser irradiation, however, no obvious malignant necrosis was found in the other three groups (Fig. 13e–h). All the results demonstrated that Ag2S@DP-FA had good ability of target and PTT.

Fig. 13.

Infrared thermal images of HeLa tumor-bearing nude mouse tail intravenously injected with Ag2S@DP-FA (a) or saline (b) on different times under 808 nm laser irradiation; the temperature of tumor evolution curves over time (c) (n = 5), **meant great significant difference (p < 0.01); representative photos of tumor-bearing nude mouse after treatments over time (d); H&E stain of tumor tissues from different treatment groups (e–h)

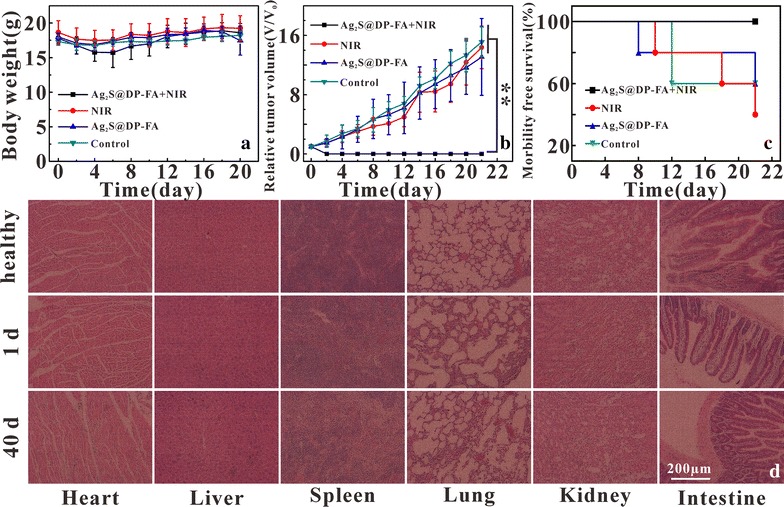

The in vivo treatment toxicity was always a great concern for nanomaterials used in biomedicine, a series of works on it had been done. The changes in body weight of nude mice in four different treatment groups were recorded, and the results showed that PTT did not significantly alter body weight (Fig. 14a), indicating that treatment was safe, no significant side effect on the growth of nude mice. The tumor volumes were also measured (Fig. 14b). All irradiated tumors on mice injected with Ag2S@DP-FA disappeared and were cured without recurrence, there was great significant difference between the experiment group and the control groups (p < 0.01). In marked contrast, the other three groups all showed similarly rapid tumor growth. Considering a survival cutoff criteria, when the aggregate tumour burden > 1 cm in diameter, the mouse was euthanasia. The survival curve showed that mice in the three control groups died successively after 8 days, while mice in the treated group were survived over 22 days without a single death (Fig. 14c). Major organs of Ag2S@DP-FA treated mice whose tumors were eliminated by the PTT were collected after 1 and 40 days for histology analysis. No noticeable signal of organ damage and tumor spread were observed from H&E stained organ slices (Fig. 14d) comparing with healthy nude mice. These works all meant that our therapy was effective without obvious toxicity.

Fig. 14.

Body weight curves (a), tumor growth curves (b) and survival curve (c) after different treatments (n = 5), **meant great significant difference (p < 0.01); H&E stained images of major organs from healthy nude mice, 1 and 40 days after Ag2S@DP-FA and laser irradiation treatment mice, respectively (d)

Conclusion

In this paper, aqueous probe Ag2S@DP-FA with good dispersibility and stability was prepared by coating hydrophobic Ag2S with the mixture of FA modified DP and the other polymers. In vitro and in vivo fluorescence, photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy have demonstrated that Ag2S@DP-FA was a safe, integrated diagnosis and treatment probe with multi-mode imaging, photothermal therapy and active targeting ability, which had a great application prospect in the early diagnosis and treatment of tumor.

Additional files

Additional file 1 Video of in vivo PAI of the nude mouse before tail intravenously injection of Ag2S@DP-FA under 744 nm laser excitation.

Additional file 2 Video of in vivo PAI of same part of tumor on the nude mouse after injection for 12 h under 744 nm laser excitation.

Additional file 3 Video of in vivo PAI of same part of tumor on the nude mouse under 523 nm laser excitation.

Authors’ contributions

ZX, XY, YX, CK, ZR, LC, TF, CY, AJ, HX and SX performed experiments and acquisition the date. ZX, XY and YX contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors. ZY designed experiment and give the intellectual input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the Analytical and Testing Center (HUST) for the help of measurement. I would like to thank Pei Zhang from the Core Facility and Technical Support (Wuhan Institute of Virology) for her help with producing TEM micrographs.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1, 2 and 3.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to publish this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81471697, 81771878), Yellow Crane Talent (Science & Technology) Program of Wuhan City and Applied Basic Research Program of Wuhan City (2016060101010044), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Hust, 2016YXMS253, 2017KFXKJC002).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- Ag2S@DP-FA

Ag2S@DSPE-PEG2000-FA

- FA

folic acid

- DP

DSPE-PEG2000

- CT

computed tomography

- PAI

photoacoustic imaging

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

positron emission computed tomography

- FI

fluorescence imaging

- NIR

near-infrared

- PA

photoacoustic

- PTT

photothermal therapy

- DT

dodecanethiol

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- WBC

white blood cell

- RBC

red blood cell

- HGB

hemoglobin

- PLT

platelet

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ODE

octadecene

- DDC

dicyclohexyl carbodiimide

- calcein-AM

calcein acetoxymethyl ester

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12951-018-0367-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Xiao-Shuai Zhang, Yang Xuan and Xiao-Quan Yang contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Xiao-Shuai Zhang, Email: zhangxiaoshuai0525@163.com.

Yang Xuan, Email: xuanyang_1990@126.com.

Xiao-Quan Yang, Email: xqyang@mail.hust.edu.cn.

Kai Cheng, Email: chengkai34@126.com.

Ruo-Yun Zhang, Email: zryariel@foxmail.com.

Cheng Li, Email: orange19906@163.com.

Fang Tan, Email: 475363969@qq.com.

Yuan-Cheng Cao, Email: yuancheng.cao@jhun.deu.cn.

Xian-Lin Song, Email: songxianlin@ibp.hust.edu.cn.

Jie An, Email: 734664787@qq.com.

Xiao-Lin Hou, Email: houxl693@163.com.

Yuan-Di Zhao, Phone: +86 27-8779-2202, Email: zydi@mail.hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Cancer Incidence, Mortality from cancer and survival in men of different occupational classes. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:533–540. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000032370.56821.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao S, Chen D, Li Q, Ye J, Jiang H, Amatore C, Wang X. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of cancer cells and tumors through specific biosynthesis of silver nanoclusters. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4384–4389. doi: 10.1038/srep04384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plante M, Touhami O, Trinh XB, Renaud MC, Sebastianelli A, Grondin K, Gregoire J. Sentinel node mapping with indocyanine green and endoscopic near-infrared fluorescence imaging in endometrial cancer. A pilot study and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tao Z, Dang X, Huang X, Muzumdar MD, Xu ES, Bardhan NM, Song H, Qi R, Yu Y, Li T, Wei W, Wyckoff J, Birrer MJ, Belcher AM, Ghoroghchian PP. Early tumor detection afforded by in vivo imaging of near-infrared II fluorescence. Biomaterials. 2017;34:202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashkatov AN, Genina EA, Kochubey VI, Tuchin VV. Optical properties of human skin, subcutaneous and mucous tissues in the wavelength range from 400 to 2000 nm. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2005;38:2543–2555. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/38/15/004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aswathy RG, Yoshida Y, Maekawa T, Kumar DS. Near-infrared quantum dots for deep tissue imaging. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:1417–1435. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subila KB, Kishore Kumar G, Shivaprasad SM, George Thomas K. Luminescence properties of CdSe quantum dots: role of crystal structure and surface composition. J Phys Chem Lett. 2013;4:2774–2779. doi: 10.1021/jz401198e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim YT, Kim S, Nakayama A, Stott NE, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Selection of quantum dot wavelengths for biomedical assays and imaging. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:50–64. doi: 10.1162/153535003765276282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335:1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu M, Wang LV. Photoacoustic imaging in biomedicine. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:041101. doi: 10.1063/1.2195024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manohar S, Vaartjes SE, van Hespen JC, Klaase JM, van den Engh FM, Steenbergen W, van Leeuwen TG. Initial results of in vivo non-invasive cancer imaging in the human breast using near-infrared photoacoustics. Opt Express. 2007;15:12277–12285. doi: 10.1364/OE.15.012277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao C, Conde J, Pan F, Li C, Zhan C, Tian F, Liang S, de la Fuente JM, Cui D. Gold nanoprisms as a hybrid in vivo cancer theranostic platform for in situ photoacoustic imaging, angiography, and localized hyperthermia. Nano Res. 2016;9:1043–1056. doi: 10.1007/s12274-016-0996-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Y, Xu B, Fu T, Cai M, Li F, Zhang Y. Wang Q. Near-infrared photoluminescent Ag2S quantum dots from a single source precursor. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1470–1471. doi: 10.1021/ja909490r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Lu Y, Li Y, Jiang J, Cheng L, Liu Z, Guo L, Pan Y, Gu H. Synthesis of Au–Fe3O4 heterostructured nanoparticles for in vivo computed tomography and magnetic resonance dual model imaging. Nanoscale. 2014;6:199–202. doi: 10.1039/C3NR04730J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang G, Ye D, Zhang X, Dong F, Chen H, Zhang S, Li J, Shen X, Kong J. One-pot synthesis of Gd3+-functionalized gold nanoclusters for dual model (fluorescence/magnetic resonance) imaging. J Mater Chem. 2013;1:3545–3552. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20440e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai W, Chen K, Li ZB, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Dual-function probe for PET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor vasculature. Med Technol. 2007;48:1862–1870. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li K, Liu B. Polymer-encapsulated organic nanoparticles for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging. Soc Rev. 2014;43:6570–6597. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00014E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan A, Scholz R, Wust P, Fähling H, Felix R. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia (MFH): cancer treatment with AC magnetic field induced excitation of biocompatible superparamagnetic nanoparticles. J Magn Magn Mater. 1999;201:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0304-8853(99)00088-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conde J, Oliva N, Zhang Y, Artzi N. Local triple-combination therapy results in tumour regression and prevents recurrence in a colon cancer mode. Nat Mater. 2016;15:1128–1138. doi: 10.1038/nmat4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, Chen Y, Li X, Gao W, Zhang L, Liu J, Zheng Y, Chen H, Shi J. Injectable 2D MoS2-integrated drug delivering implant for highly efficient NIR-triggered synergistic tumor hyperthermia. Adv Mater. 2015;27:7117–7122. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagley AF, Hill S, Rogers GS, Bhatia SN. Plasmonic photothermal heating of intraperitoneal tumors through the use of an implanted near-infrared source. ACS Nano. 2013;7:8089–8097. doi: 10.1021/nn4033757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wust P, Hildebrandt B, Sreenivasa G, Rau B, Gellermann J, Riess H, Felix R, Schlag PM. Hyperthermia in combined treatment of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:487–497. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng L, He W, Gong H, Wang C, Chen Q, Cheng Z, Liu Z. PEGylated micelle nanoparticles encapsulating a non-fluorescent near-infrared organic dye as a safe and highly-effective photothermal agent for in vivo cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:5893–5902. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201301045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yguerabide J, Yguerabide EE. Light-scattering submicroscopic particles as highly fluorescent analogs and their use as tracer labels in clinical and biological applications: II. Experimental characterization. Anal Biochem. 1998;262:157–176. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao J, Wu C, Deng D, Wu P, Cai C. Direct synthesis of water-soluble aptamer-Ag2S quantum dots at ambient temperature for specific imaging and photothermal therapy of cancer. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:2437–2449. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang T, Tang Y, Liu L, Lv X, Wang Q, Ke H, Deng Y, Yang H, Yang X, Liu G, Zhao Y, Chen H. Size-dependent Ag2S nanodots for second near-infrared fluorescence/photoacoustics imaging and simultaneous photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:1848–1857. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blume G, Cevc G. Liposomes for the sustained drug release in vivo. Biophys Acta. 1990;1029:91–97. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90440-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You J, Li X, Cui F, Du YZ, Yuan H, Hu F. Folate-conjugated polymer micelles for active targeting to cancer cells: preparation, in vitro evaluation of targeting ability and cytotoxicity. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:045102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/04/045102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bharali DJ, Lucey DW, Jayakumar H, Pudavar HE, Prasad PN. Folate-receptor-mediated delivery of InP quantum dots for bioimaging using confocal and two-photon microscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11364–11371. doi: 10.1021/ja051455x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Wang Q, Luo Q, Yang X. Fluorescence molecular tomography in the second near-infrared window. Opt Express. 2015;23:12669–12679. doi: 10.1364/OE.23.012669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Cai X, Maslov K, Wang L, Luo Q. High-resolution photoacoustic microscope for rat brain imaging in vivo. Chin Opt Lett. 2010;8:609–611. doi: 10.3788/COL20100806.0609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Yang X, Gong H, Jiang B, Wang H, Xu G, Deng Y. Assessing the effects of norepinephrine on single cerebral microvessels using optical-resolution photoacoustic microscope. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:076007. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.7.076007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong G, Robinson JT, Zhang Y, Diao S, Antaris AL, Wang Q, Dai H. In vivo fluorescence imaging with Ag2S quantum dots in the second near-infrared region. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;124:9956–9959. doi: 10.1002/ange.201206059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Hong G, Zhang Y, Chen G, Li F, Dai H, Wang Q. Ag2S quantum dot: a bright and biocompatible fluorescent nanoprobe in the second near-infrared window. ACS Nano. 2012;6:3695–3702. doi: 10.1021/nn301218z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabizon A, Horowitz AT, Goren D, Tzemach D, Mandelbaum-Shavi F, Qazen MM, Zalipsky S. Targeting folate receptor with folate linked to extremities of poly (ethylene glycol)-grafted liposomes: in vitro studies. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:289–298. doi: 10.1021/bc9801124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, Van Bre C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu F, Wu SH, Hung Y, Mou CY. Size effect on cell uptake in well-suspended, uniform mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:1408–1413. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerlier D, Thomasset N. Use of MTT colorimetric assay to measure cell activation. J Immunol Methods. 1986;94:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh-Hora M, Yamashita M, Hogan PG, Sharma S, Lamperti E, Chung W, Prakriya M, Feske S, Rao A. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:432–443. doi: 10.1038/ni1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Y, Zhang C, Chen X, Jiang H, Pan S, Easteal AJ, Sun X. The influence of modified pluronic F127 copolymers with higher phase transition temperature on arsenic trioxide-releasing properties and toxicity in a subcutaneous model of rats. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012;13:441–447. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9756-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Video of in vivo PAI of the nude mouse before tail intravenously injection of Ag2S@DP-FA under 744 nm laser excitation.

Additional file 2 Video of in vivo PAI of same part of tumor on the nude mouse after injection for 12 h under 744 nm laser excitation.

Additional file 3 Video of in vivo PAI of same part of tumor on the nude mouse under 523 nm laser excitation.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1, 2 and 3.