Abstract

Background and Aims:

Pain after modified radical mastectomy (MRM) has been successfully managed with thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of adding dexamethasone or ketamine as adjuncts to bupivacaine in TPVB on the quality of postoperative analgesia in participants undergoing MRM.

Methods:

This prospective randomised controlled study enrolled ninety adult females scheduled for MRM. Patients were randomised into three groups (30 each) to receive ultrasound-guided TPVB before induction of general anaesthesia. Group B received bupivacaine 0.5% + 1 ml normal saline, Group D received bupivacaine 0.5% + 1 ml dexamethasone (4 mg) and Group K received bupivacaine 0.5% + 1 ml ketamine (50 mg). Patients were observed for 24 h postoperatively to record time to first analgesic demand as a primary outcome, pain scores, total rescue morphine consumption and incidence of complications.

Results:

Group K had significantly longer time to first analgesic demand than group D and control group (18.0 ± 6.0, 10.3 ± 4.5 and 5.3 ± 3.1 hours respectively; P = 0.0001). VAS scores were significantly lower in group D and group K compared to control group at 6h and 12 h postoperative (p 0.0001 and 0.0001 respectively) while group K had lower VAS at 18 hours compared to other two groups (P = 0.0001). Control group showed the highest mean 24 h opioid consumption (8.9 ± 7.9 mg) compared to group D and group K (3.60 ± 6.92 and 2.63 ± 5.24 mg, P = 0.008,0.001 respectively). No serious adverse events were observed.

Conclusion:

Ketamine 50 mg or dexamethasone 4 mg added to bupivacaine 0.5% in TPVB for MRM prolonged the time to first analgesic request with no serious side effects.

Key words: Analgesia, dexamethasone, ketamine, mastectomy, modified radical

INTRODUCTION

Post-operative pain experienced after mastectomy operation is known to have a number of shortcomings such as poor recovery, prolonged hospital stay and even increased liability to chronic persistent pain.[1] Hence, a variety of techniques have been introduced including local anaesthetic infiltration, intercostal block, thoracic epidural anaesthesia, pectoral nerves block and paravertebral block (PVB), to keep post-operative pain to the minimum.[2]

The paravertebral space is a potential space that contains spinal nerves, white and grey rami communicantes, the sympathetic chain, intercostal vessels and fat.[3] Local anaesthetics injected into this space directly infiltrate both spinal nerves and sympathetic chain, producing a dense block.[4]

The limited duration of analgesia provided by local anaesthetics has warranted the use of various adjuvants, for example tramadol, epinephrine, clonidine or dexmedetomidine, aiming at synergistically enhancing the quality of analgesia.[5,6]

Our study was meant to test the hypothesis that adding an adjuvant to bupivacaine, namely dexamethasone or ketamine, administered as a single injection in ultrasound (U/S)-guided PVB would enhance the quality of post-operative analgesia after modified radical mastectomy.

METHODS

This prospective double-blind randomised study was conducted between July 2016 and June 2017, enrolling 90 female patients scheduled for MRM, whose age ranged from 18 to 60 years with American Society of Anesthesiologists' (ASA) physical status I or II, after the approval of our Institutional Ethics Committee (identification number 31760/09/17) and obtaining a written informed consent from all the consenting participants. Exclusion criteria included patients' refusal, severe respiratory or cardiac disorders, hepatic or renal insufficiency, coagulopathy, local infection at injection site, spine deformity, allergy to any of the study drugs or to their similar classes, pregnancy or breast-feeding, severe obesity (body mass index >35 kg/m2) and psychiatric disease.

A preoperative visit was conducted for history taking, clinical examination and routine laboratory investigations, and the patients were shown how to use the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS); 0–10 point where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain. On arrival to the operating theatre, an intravenous (IV) access was established and standard monitoring in terms of electrocardiogram (ECG), non-invasive blood pressure and pulse oximeter for oxygen saturation (SpO2) was applied to all participants.

Patients received midazolam 0.05 mg/kg and a prophylactic anti-emetic in the form of ondansetron 4 mg IV prior to performing the block. They were randomly assigned to three groups of 30 patients each, at 1:1:1 allocation ratio using computer-generated random numbers concealed in sealed opaque envelopes. Group B (control group) received 19 ml plain bupivacaine 0.5% plus 1 ml normal saline, group D (dexamethasone group) received bupivacaine as group B plus 1 ml dexamethasone 4 mg, and group K (ketamine group) received bupivacaine as group B plus 1 ml ketamine 50 mg. All the medications were prepared by an anaesthesiologist not participating in the study.

Thoracic paravertebral blocks were performed at T4 level with the patients in sitting position. The site of the paravertebral block was sterilised using povidone iodine solution, and a high-frequency linear transducer probe (6–12 MHz), connected to ultrasound (USG) machine (Sonoscape® SSI- 6000, China) was covered by a disposable sterile cover. The probe was placed vertically; lateral to the spinous process at the same side of surgery to attain a parasagittal view of the transverse processes, pleura, and superior costotransverse ligaments.

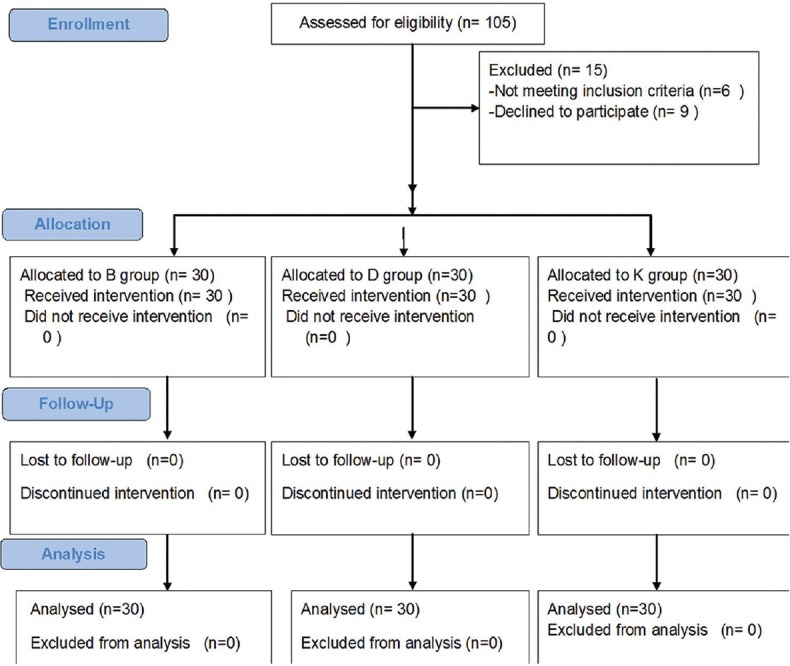

After localisation of the paravertebral space by USG, a 25-gauge needle was inserted 2.5 cm lateral to the cephalic edge of the spinous process of the fourth thoracic vertebra, and skin and subcutaneous tissue were infiltrated with 5 ml of lidocaine 2%. Afterwards, a 22 gauge, 50-mm, blunt insulated nerve block needle (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA) was directed in an in-plane approach relative to the ultrasound transducer towards the paravertebral space. The needle was advanced under direct vision in a cephaled orientation to puncture the superior costotransverse ligament at the desired level. Negative aspiration for blood was then confirmed, prior to injecting the study medications. Proper spread of the drug in the paravertebral space was confirmed by anterior displacement of the pleura. A skilled anaesthesiologist who was not involved in data collection performed all the blocks. A pinprick was utilised to ensure the successfulness of the block, and the onset of sensory block was recorded. If no block was attained within 30 minutes, patients were excluded from the data analysis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of participants through each stage of the randomized trial

All patients received the same general anaesthetic technique, induction was done using fentanyl 1 μg/kg IV, propofol 2 mg/kg IV and cisatracurium 0.15 mg/kg IV to facilitate endotracheal intubation, maintenance of anaesthesia afterward was achieved by isoflurane 1.5-2% in oxygen and air mixture, cisatracurium 0.03 mg/kg as required. End-tidal capnogram (ETCO2) was kept between 35 and 40 mmHg by adjusting the ventilator parameters. Any increase of heart rate (HR) or mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) more than 20% above the baseline following the skin incision or at any time during the procedure was defined as insufficient analgesia, and additional fentanyl 1 μg/kg IV would be given. After completion of the surgical procedure, the residual neuromuscular block was antagonised by neostigmine 2.5 mg with atropine 1 mg and extubation was done after fulfillment of its criteria.

All patients were kept under observation in the post anaesthesia care unit (PACU) for 6 hours before being moved to the ward. Analgesia was provided on a regular basis with intravenous acetaminophen 1 g every six hours.

Pain scores were evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS) on patient's arrival to the PACU, then at 2, 6, 12, 18 and 24 hours postoperatively. A rescue dose of analgesia in the form of morphine 0.1 mg/kg was given to patients with VAS score equal to or above four. The interval between the injection of local anaesthetic solution and the patient's first request for analgesia was recorded, together with the total dose of morphine administered in the first 24 hours postoperatively. After taking baseline parameters before induction of general anaesthesia, haemodynamic parameters were recorded at skin incision and then every 30 minutes until the end of surgery. Complications comprising postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) were recorded, and metoclopramide 10 mg IV 8 hourly was given when needed. Other complications related to the technique or to the drugs used (pneumothorax, local anaesthetic toxicity, psychomimetic changes defined as agitation, hallucinations, or vivid dreams up to 24 h after the surgery) were also recorded.

Our primary outcome was the time to first analgesic request. Based on the results of a previous study,[7] the mean value of time to request first rescue analgesic was found to be 594.40 ± 71.78 minutes in patients receiving dexamethasone. A sample size of at least 25 patients was needed in each group to detect a significant difference in means of the time of first analgesic requirement of 75 minutes between dexamethasone and ketamine groups with a standard deviation of 71.78 at α error of 0.05 and power of study of 95%. Hence, in this study, 30 cases were enrolled per each group to overcome possible dropouts. Our secondary outcomes were pain scores, 24 h rescue morphine administration, haemodynamic parameters and incidence of complications.

The statistical software SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Normality of data was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The parametric data were expressed as mean ± SD and was analysed utilizing One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's test. VAS score was presented as median (interquartile range) and analysed among the studied groups utilising the Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical data were presented as patients' number (%) and were analysed utilising the Chi-square test. Within each group, the numerical data were compared utilising repeated measures analysis of variance while the non-parametric data were analysed utilising the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and five patients were found eligible for the study. Of those, six patients had one or more exclusion criteria (four patients had bleeding disorders and two patients had body mass index >35 kg/m2) and nine patients refused to participate, so ninety patients were enrolled and randomly allocated into one of the three groups (30 patients each) [Figure 1].

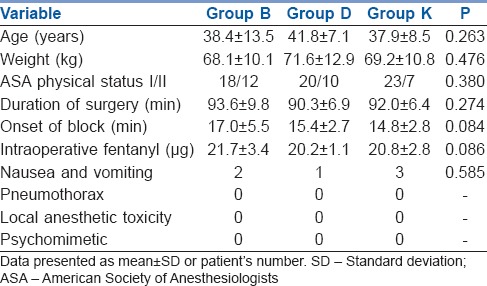

The study groups were comparable in demographic data and duration of surgery. Successful block was accomplished in all patients with no significant difference among the three groups with regard to the onset of block or intraoperative fentanyl consumption (P = 0.084, 0.086 respectively) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data and incidence of complications in the three groups

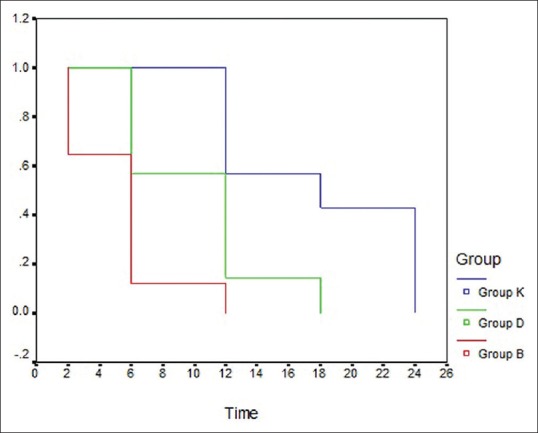

The time to first analgesic requirement was significantly prolonged in dexamethasone group (10.3 ± 4.5 h) and ketamine group (18.0 ± 6.0 h) as compared to the control group (5.3 ± 3.1 h). It was longer in ketamine group as compared to dexamethasone group (P = 0.001) [Figure 2]. Postoperative consumption of rescue analgesia (IV morphine) was significantly lower in dexamethasone group (3.6 ± 6.9 mg) and ketamine group (2.6 ± 5.2 mg) as compared to the control group (8.9 ± 7.9 mg) with P = 0.008, 0.001 respectively. However, the comparison between the dexamethasone group and the ketamine group showed insignificant difference (P = 0.369).

Figure 2.

The Kaplan–Meier curves to depict the time to first rescue analgesia in the three groups

The pain scores were comparable between the three groups on admission to the PACU, at 2 h and 24 h postoperatively (P value 0.938, 0.184, and 0.853 respectively). However, at 6 hours and 12 hours, patients in dexamethasone group and ketamine group had better VAS scores than the control group, while at 6 h and 18 h the pain scores were significantly lower in ketamine group compared to dexamethasone and control groups. Although statistically significant, differences in VAS score were clinically limited [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Visual analogue scale changes in the three groups. Data presented as median (interquartile range)

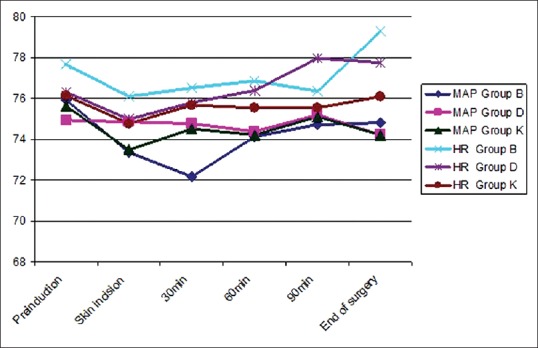

Patients had a stable haemodynamic profile at all times of measurements with no significant difference between the three groups [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) and heart rate (beat/min) changes in the three groups. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation

Side effects in terms of PONV were comparable in the three groups. Psychomimetic changes were not observed in any patient of this study. Moreover, no patients showed manifestations of pneumothorax or local anaesthetic toxicity [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated the enhanced analgesic effect that is acquired by using dexamethasone and ketamine as adjuvants to bupivacaine in USG-guided thoracic PVBs in patients undergoing MRM. Both drugs showed improved postoperative analgesia with less morphine consumption, compared to administration of bupivacaine alone. However, lower postoperative pain scores, coupled with longer time to first rescue analgesic requirement were observed in ketamine group as compared to dexamethasone group.

TPVB is often used before breast surgery with the aim of providing intraoperative and post-operative analgesia, with fewer adverse effects when compared to general anaesthesia alone.[8] A study conducted at a large multi-disciplinary centre for cancer on 313 participants, reported that PVBs before breast surgery were associated with better pain control in the short-term and reduced length of hospital stay compared to patients who had not received the block.[9] Numerous adjuvants have been employed to prolong the duration and enhance the quality of post-operative pain control.[6] This is of particular importance, especially in breast surgeries where adequate control of post-operative pain is an integral element in preventing its transition from acute to chronic pain.[10]

The analgesic effect of dexamethasone and ketamine in regional nerve block had been reported in several studies.[11,12,13,14] However, to the best of our knowledge, no clinical studies have examined the comparison between the effects of dexamethasone and ketamine as adjuncts to local anaesthetics in the PVB.

Dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid with known potent long-acting effects. When combined with local anaesthetics, it prolongs their duration by preventing the propagation of pain signals along the myelinated C fibres.[15] Moreover, more studies have shown recently that systemic IV administration of dexamethasone results in a similar potentiation of local anaesthetic effects.[16,17] However, a previous research demonstrated that perineural but not IV administration of 4 mg dexamethasone, which is equivalent to the dose used in our study, significantly prolonged the effect of post-operative analgesia achieved by interscalene nerve block with 20 mL of 0.75% ropivacaine.[18] In addition, one more study demonstrated that injection of dexamethasone 5 mg perineurally is more effective than the IV route when administered as an adjuvant in the interscalene block, with regard to the analgesic duration in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.[19]

The antinociceptive effect of ketamine is mainly due to blocking of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors which are thought to be scattered all over the nervous system of the human body. Other probable mechanisms of ketamine action include a combination of opioid system sensitization and aminergic (serotonergic and noradrenergic) activation with inhibition of reuptake. Furthermore, ketamine has a direct inhibitory effect on nitric oxide synthase, which probably contributes to some extent to its analgesic effects.[20]

Our findings were consistent with a previous study on sixty patients undergoing elective nephrectomy; they reported that dexamethasone administered as an adjuvant to 0.25% bupivacaine for TPVB, lowered the pain score, prolonged the duration of analgesia and decreased the consumption of rescue opioids in the first 24 h in comparison to 0.25% bupivacaine alone.[15] In addition,[21] an observational study to investigate the effectiveness and safety of bilateral TPVB in the PACU, which was used to alleviate pain in participants following laparotomy, concluded that bilateral TPVB with an injection of 25 ml of 0.2% ropivacaine and 5 mg dexamethasone led to a rapid reduction of pain scores at rest and on cough and omitted the need for rescue analgesia in patients with exaggerating pain. The effective analgesia with quick onset could be explained by the enhancement of local anaesthetic penetration to the spinal nerve in the thoracic paravertebral space since they are devoid of both epineurium and a part of the perineurium, with just a thin membranous root sheath.[22]

Another study also found that the combination of 8 mg dexamethasone with 0.25% levobupivacaine for the TPVB in patients undergoing thoracotomy, provided superior post-operative analgesia compared to 0.25% levobupivacaine alone, which was in agreement with our results.[23] Furthermore, the use of bupivacaine combined with adjuvant dexamethasone has been reported to extend the duration of post-operative analgesia in comparison to its combination with clonidine when injected through a paravertebral catheter in thoracic and upper abdominal surgeries.[7]

A previously published study evaluated the use of ketamine 50 mg and dexamethasone 8 mg as adjuvants to a local anaesthetic mixture (lidocaine 2% + bupivacaine 0.5%) and demonstrated a significant decrease in onset time of sensory and motor blocks, prolonged duration of post-operative analgesia and lower analgesic consumption as compared to local anaesthetics alone in patients undergoing combined sciatic-femoral nerve block.[24] In another study, the addition of 1 mg/kg ketamine to 0.25% bupivacaine for modified pectoral nerves block in breast cancer surgery has been shown to be beneficial, as evidenced by prolonged time to first rescue analgesia and reduced total opioid consumption in ketamine group compared to bupivacaine only group but with no significant difference in VAS score between the two groups.[10]

In contradiction to our results, a former study found no statistically significant differences regarding pain score, time interval to post-operative analgesic request or 24 h post-operative fentanyl consumption, when ketamine 0.5 mg/kg or tramadol 1.5 mg/kg were added to bupivacaine 0.5% in PVB for modified radical mastectomy, in comparison to control group receiving bupivacaine 0.5% without additives.[25] This could be accredited, together with the raised incidence of ketamine psychomimetic events reported in their results, to the rapid absorption of the dose of ketamine they used (0.5 mg/kg) into the systemic circulation and also the inability to detect any local anaesthetic effect probably owing to the use of long-acting local anaesthetic (bupivacaine). The differences between their results and ours are attributed to several reasons. First, they had a smaller sample size. Second, they injected ketamine at two levels: At T1 (1/3 of the dose) and T4 (2/3 of the dose), while we injected the whole volume only at T4 level. Third, induction of general anaesthesia was done without testing the sensory level attained by the TPVB in their study in contrast to ours, so there might have been cases with failed blocks.

Patients of our study had a comparable stable haemodynamic profile at all times of measurement. TPVB provides unilateral analgesia and sympathetic block leading to less influence on patient's haemodynamics.[26]

Despite the correlation between breast cancer surgery and high rate of nausea and vomiting,[27] the incidence of PONV in our study population was infrequent. The anti-emetic property of the induction agent propofol, and the use of prophylactic antiemetic ondansetron, in our study may have contributed to this finding. Furthermore, a reduction in PONV after breast surgery has been reported with the use of the PVB.[28]

In our study, we chose to inject bupivacaine 0.5% instead of the commonly employed 0.25% concentration to ensure good quality of the block with prolonged duration of analgesia which could be provided by 0.5% bupivacaine as proved in other studies,[29,30] especially in the control group with no added adjuvant. We also injected identical volumes of local anaesthetic (19 ml) in all patients to avoid introducing a bias to our results by infiltrating different weight-based volumes. This study had several limitations. First, pain scores were evaluated at rest only not during a cough or movement. Second, we applied a single-level injection block; we did not use multiple-level injection or catheter insertion techniques which could have effectively contributed to the improvement of the quality of analgesia.

Our study findings could be generalised to other types of breast surgeries and thoracotomy procedures, however, future studies for investigating different doses of ketamine are highly recommended to find out the appropriate safe dose associated with supreme improvement of the efficacy of paravertebral analgesia.

CONCLUSION

Dexamethasone and ketamine, used as adjuncts to bupivacaine for thoracic PVB in female patients undergoing elective modified radical mastectomy, prolong the time to first analgesic request.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poleshuck EL, Katz J, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, et al. Risk factors for chronic pain following breast cancer surgery: A prospective study. J Pain. 2006;7:626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashandy GM, Abbas DN. Pectoral nerves I and II blocks in multimodal analgesia for breast cancer surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:68–74. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tighe S, Greene MD, Rajadurai N. Paravertebral block. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2010;10:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kairaluoma PM, Bachmann MS, Korpinen AK, Rosenberg PH, Pere PJ. Single-injection paravertebral block before general anesthesia enhances analgesia after breast cancer surgery with and without associated lymph node biopsy. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1837–43. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136775.15566.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari AK, Tomar GS, Agrawal J. Intrathecal bupivacaine in comparison with a combination of nalbuphine and bupivacaine for subarachnoid block: A randomized prospective double-blind clinical study. Am J Ther. 2013;20:592–5. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31822048db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohta M, Kalra B, Sethi AK, Kaur N. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant in paravertebral block in breast cancer surgery. J Anesth. 2016;30:252–60. doi: 10.1007/s00540-015-2123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govardhani Y, Sudhakar B, Ussa Varaprasad N. A comparative study of 0.125% bupivacaine with dexamethsone and clonidine through single space paravertebral block for post-operative analgesia in thoracic and upper abdominal surgeries. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2014;1:1792–800. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arunakul P, Ruksa A. General anesthesia with thoracic paravertebral block for modified radical mastectomy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93(Suppl 7):S149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boughey JC, Goravanchi F, Parris RN, Kee SS, Frenzel JC, Hunt KK, et al. Improved postoperative pain control using thoracic paravertebral block for breast operations. Breast J. 2009;15:483–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Othman AH, El-Rahman AM, El Sherif F. Efficacy and safety of ketamine added to local anesthetic in modified pectoral block for management of postoperative pain in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy. Pain Physician. 2016;19:485–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biradar PA, Kaimar P, Gopalakrishna K. Effect of dexamethasone added to lidocaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block: A prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:180–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.111850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bani-Hashem N, Hassan-Nasab B, Pour EA, Maleh PA, Nabavi A, Jabbari A, et al. Addition of intrathecal dexamethasone to bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia in orthopedic surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:382–6. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Ghaffar HS, Kalefa MA, Imbaby AS. Efficacy of ketamine as an adjunct to lidocaine in intravenous regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39:418–22. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Himmelseher S, Ziegler-Pithamitsis D, Argiriadou H, Martin J, Jelen-Esselborn S, Kochs E, et al. Small-dose S(+)-ketamine reduces postoperative pain when applied with ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia for total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1290–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomar GS, Ganguly S, Cherian G. Effect of perineural dexamethasone with bupivacaine in single space paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in elective nephrectomy cases: A Double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e713–7. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desmet M, Braems H, Reynvoet M, Plasschaert S, Van Cauwelaert J, Pottel H, et al. IV and perineural dexamethasone are equivalent in increasing the analgesic duration of a single-shot interscalene block with ropivacaine for shoulder surgery: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:445–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld DM, Ivancic MG, Hattrup SJ, Renfree KJ, Watkins AR, Hentz JG, et al. Perineural versus intravenous dexamethasone as adjuncts to local anaesthetic brachial plexus block for shoulder surgery. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:380–8. doi: 10.1111/anae.13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawanishi R, Yamamoto K, Tobetto Y, Nomura K, Kato M, Go R, et al. Perineural but not systemic low-dose dexamethasone prolongs the duration of interscalene block with ropivacaine: A prospective randomized trial. Local Reg Anesth. 2014;7:5–9. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S59158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chun EH, Kim YJ, Woo JH. Which is your choice for prolonging the analgesic duration of single-shot interscalene brachial blocks for arthroscopic shoulder surgery? Intravenous dexamethasone 5mg vs. perineural dexamethasone 5mg randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3828. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleigh J, Harvey M, Voss L, Denny B. Ketamine – More mechanisms of action than just NMDA blockade. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2014;4:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu F, Zhang H, Zuo Y. Bilateral thoracic paravertebral block for immediate postoperative pain relief in the PACU: A prospective, observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:89. doi: 10.1186/s12871-017-0378-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baik JS, Oh AY, Cho CW, Shin HJ, Han SH, Ryu JH, et al. Thoracic paravertebral block for nephrectomy: A randomized, controlled, observer-blinded study. Pain Med. 2014;15:850–6. doi: 10.1111/pme.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharjee DP, Piplai G, Nayak S, Maity AR, Ghosh A, Karmakar M, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the efficacy of dexamethasone to provide postoperative analgesia after paravertebral block in patients undergoing elective thoracotomy. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2013;2:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attia J, Sayed N, Hasanin A. Ketamine versus dexamethasone as an adjuvant to local anesthetics in combined sciatic-femoral nerve block for below knee surgeries. Pain Pract. 2016;16:123. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omar AM, Mansour MA, Abdelwahab HH, Aboushanab OH. Role of ketamine and tramadol as adjuncts to bupivacaine 0.5% in paravertebral block for breast surgery: A randomized double-blind study. Egypt J Anaesth. 2011;27:101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies RG, Myles PS, Graham JM. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs. epidural blockade for thoracotomy – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:418–26. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aufforth R, Jain J, Morreale J, Baumgarten R, Falk J, Wesen C, et al. Paravertebral blocks in breast cancer surgery: Is there a difference in postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting? Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:548–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fahy AS, Jakub JW, Dy BM, Eldin NS, Harmsen S, Sviggum H, et al. Paravertebral blocks in patients undergoing mastectomy with or without immediate reconstruction provides improved pain control and decreased postoperative nausea and vomiting. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3284–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta K, Srikanth K, Girdhar KK, Chan V. Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided paravertebral block versus serratus plane block for modified radical mastectomy: A randomised, controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61:381–6. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_62_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulroy MF, Larkin KL, Batra MS, Hodgson PS, Owens BD. Femoral nerve block with 0.25% or 0.5% bupivacaine improves postoperative analgesia following outpatient arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament repair. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:24–9. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]