Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to compare patients with PHC with lymph node metastases (LN+) who underwent a resection with patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy.

Methods

Consecutive LN+ patients who underwent a resection for PHC in 12 centers were compared with patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy in 2 centers.

Results

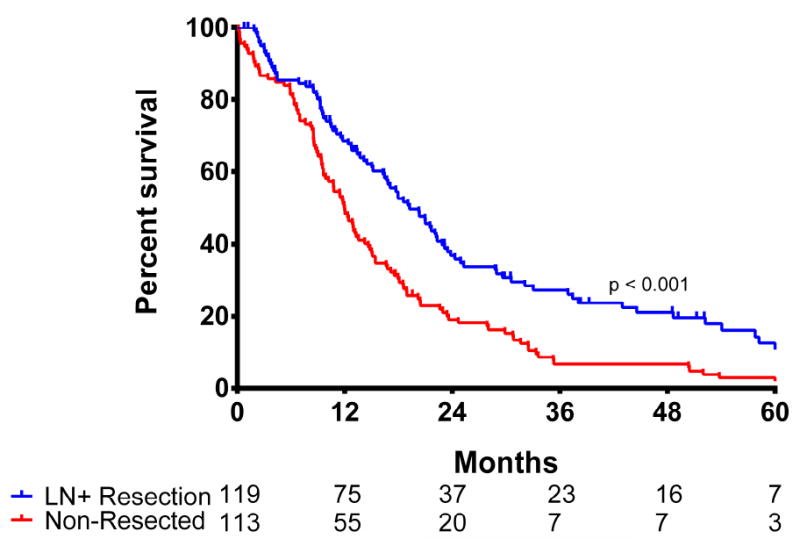

In the resected cohort of 119 patients, the median overall survival (OS) was 19 months and the estimated 1-, 3- and 5-year OS was 69%, 27% and 13%, respectively. In the non-resected cohort of 113 patients, median OS was 12 months and the estimated 1-, 3- and 5-year OS was 49%, 7%, and 3%, respectively. OS was better in the resected LN+ cohort (p<0.001). Positive resection margin (hazard ratio [HR]:1.54; 95%CI:0.97-2.45) and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (HR:1.71; 95%CI:1.09-2.69) were independent poor prognostic factors in the resected cohort.

Conclusion

Patients with PHC who underwent a resection for LN+ disease had better OS than patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy. LN+ PHC does not preclude 5-year survival after resection.

Keywords: perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, lymph nodes, survival

Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PHC) is the most common bile duct cancer, with an annual incidence in Western countries of around 2 per 100.000.(1, 2) Patients usually present with obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, and weight loss (2, 3). Surgical resection is the only potentially curative option for patients with PHC, resulting in a median overall survival (OS) of about 35-40 months.(4-7) At diagnosis, however, most patients are ineligible for resection because of locally advanced or metastatic disease.(8-10) Resection typically involves a right or left (extended) hemihepatectomy with an extrahepatic bile duct resection.(2) These extensive operations have considerable major postoperative morbidity and mortality of 5 to 15% in Western centers.(11, 12) Patient selection is paramount to make a trade-off between the potential improved OS and quality of life (QoL) after surgery versus the substantial postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Lymph node metastases (LN+) have been reported to be the major determinant of OS.(2, 13, 14) In a recent study conducted in a large international cohort, patients with lymph node metastases had an estimated 100% chance of recurrence.(15) However, resection of LN+ PHC may still improve life expectancy. The aim of this multi-institutional study was to compare survival of patients with PHC with LN+ who underwent a resection with patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, the resected cohort consisted of patients with PHC who underwent curative-intent surgical resection between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2014 at one of twelve academic institutions in the United States and Western Europe were identified (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Stanford University, Stanford, California; University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; New York University, New York, New York; University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky; Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The non-resected cohort consisted of patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy from two centers (Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands). Patients with locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy were found to have vascular or biliary involvement precluding a complete resection with adequate liver remnant or had lymph node metastases (N1 or N2). When the reason for discontinuation of the resection was suspicion of extensive lymph node metastases, frozen analysis was conducted to confirm the suspicion. In both cohorts, patients were excluded if they had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 3 or 4 at presentation, distant metastases (M1) on preoperative imaging, at staging laparoscopy, or laparotomy.

Sociodemographic and clinicopathologic data were collected, including age and sex, as well as tumor size, tumor stage, presence of nodal disease, final resection margin, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI). A major hepatectomy was defined as a hepatic resection of more than 3 Couinaud segments. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition staging, involvement of lymph nodes within the hepatoduodenal ligament was classified as N1, and lymph node involvement beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament (i.e. along the common hepatic artery and celiac trunc) as N2.(16, 17) Margin status was categorized as R0 for a negative transection margin, R1 when the margin was microscopically positive, and R2 when the margin was macroscopically positive. For the patients who underwent surgical resection, postoperative complications occurring within 30 days after surgery, during index admission, or during readmission within 30 days after discharge were recorded. 90-day postoperative mortality was registered. The severity of postoperative complications was scored according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.(18) Severe postoperative complications were defined as those with a Clavien-Dindo Grade IIIa or higher (i.e. requiring re-intervention). The respective institutional review boards of each participating institution approved this study.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described as whole numbers and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile range (IQR). Percentages for each variable were calculated based on available data, excluding missing values. Univariable comparison of categorical variables was performed using the Pearson chi-square test. Univariable comparison of continuous variables was performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The primary outcome of the study was OS. OS was calculated from the date of operation to the date of death or last follow-up and estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Last follow-up was defined as the last contact with the treating institution. Univariate and multivariable hazard ratios were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards method. Risk factors were included in the multivariable model if the p-value was below 0.10 in univariate analysis. All tests were 2-sided and p < 0.05 defined statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, New York).

Results

Demographic and Clinicopathologic Characteristics

The resected cohort included 119 LN+ PHC patients who underwent a curative intent resection. The non-resected cohort included 113 patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy. The reason for aborting the procedure was the extent of LN+ in 49 patients (43%). In 64 patients, the extent of vascular and or biliary involvement precluded surgery. The two cohorts are compared in Table 1. Table 2 presents resection characteristics of the resection cohort only. A notable difference between the resected cohort and the non-resected patients was observed in the administration of chemotherapy. In the resected cohort, 56 patients (51%) went on to have adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas in the non-resected cohort only 8 patients (7%) received chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Treatment Groups

| Variable | Lymph-Node Positive Resection (n = 119) | Non-Resected Patients (n = 113) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Gender | 42 (35) | 38 (34) | 0.790 |

| Age, years | 65 (55-72) | 65 (55-70) | 0.593 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 (22-28) | 24 (22-27) | 0.054 |

| Clinical Jaundice at Presentation | 99 (85) | 89 (81) | 0.373 |

| Bismuth Classification on imaging | |||

| I | 5 (5) | 12 (11) | 0.318 |

| II | 14 (13) | 10 (9) | |

| IIIA | 35 (32) | 28 (25) | |

| IIIB | 26 (24) | 30 (27) | |

| IV | 30 (27) | 33 (29) | |

| Vascular Involvement (hepatic artery or portal vein, on imaging) | 57 (56) | 76 (69) | 0.057 |

| N2 Lymph Node Metastases, pathologically confirmed | 9 (8) | 7 (12) | 0.364 |

Table 2.

Resection Details and Postoperative Course After Lymph-Node Positive Resection

| Variable | Lymph-Node Positive Resection (n = 119) |

|---|---|

| ASA | |

| I | 10 (8) |

| II | 41 (43) |

| III | 42 (44) |

| IV | 3 (3) |

| Drainage Preoperative | |

| None | 23 (19) |

| Percutaneous | 45 (38) |

| Endoscopic | 22 (19) |

| Both | 29 (24) |

| AJCC pT-stage | |

| pT1-pT2 | 61 (60) |

| pT3-pT4 | 40 (40) |

| Type of Resection | |

| Minor hepatectomy (< 3 Couinaud Segments) | 18 (15) |

| Major hepatectomy (≥ 3 Couinaud Segments) | 100 (85) |

| Margin Status | |

| R0 | 76 (64) |

| R1 | 42 (36) |

| Tumor Size | |

| ≤ 2.5 cm | 65 (69) |

| > 2.5 cm | 29 (31) |

| Any complication | 87 (75) |

| Clavien Dindo Grade | |

| I-II | 32 (37) |

| III-V | 55 (63) |

| Length of Stay (days) | 12 (8-19) |

| Readmission within 30 days | 16 (27) |

| Postoperative 90-day mortality | 8 (7) |

| Adjuvant Therapy | |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 56 (49) |

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 37 (34) |

Factors Associated with Overall Survival

Ninety-day postoperative mortality in the resected cohort was 7% (n = 8), which did not differ significantly from the ninety-day mortality in the non-resected patients (n = 15, 13.4%; p = 0.09). In the resected cohort, the median OS was 19.2 months and the estimated 1-, 3- and 5-year OS was 69%, 27% and 13%, respectively. Only 7 patients were alive at last follow-up with a median follow-up of 60 months. Three out of 7 patients (43%) were alive with recurrent disease, while 4 patients had no evidence of disease at a follow-up of 62, 68, 76, and 98 months. In the non-resected cohort, the median OS was 12 months and the estimated 1-, 3- and 5-year OS was 49%, 7%, and 3%, respectively, which was significantly worse compared with the resected cohort (p < 0.001; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival stratified for treatment group (p < 0.001)

In Cox regression analyses, several patient and disease specific characteristics were assessed for their correlation with OS in the resected LN+ cohort. Positive margin and LVI were associated with OS in univariate analysis, and remained associated with OS in multivariable analysis (HR 1.54, 95%CI 0.97 – 2.45, p = 0.067; HR 1.71, 95%CI 1.09 – 2.69, p = 0.019). When patients with R1 resection margins were compared with the non-resected patients, no difference in median OS was found (17 months vs. 12 months; p = 0.086; figure 2). Median OS was also comparable between resected patients with LVI and non-resected patients (16 months vs. 12 months; p = 0.073; figure 3).

Figure 2.

Overall Survival of Resected R1 Patients versus Non-Resected Patients (p = 0.086)

Figure 3.

Overall Survival of Resected Lymphovascular Invasion Patients versus Non-Resected Patients (p = 0.073)

Discussion

In an international cohort of 12 centers, LN+ patients had a median OS of 19 months after resection of PHC. These data confirm that LN+ PHC has a poor prognosis.(2, 13-15) However, resection of LN+ PHC did not preclude 5-year OS (13%). A recent study reported that LN+ disease is virtually incurable, with an estimated disease-free survival of 0% after seven years.(15) In the current study, 7 patients who were alive at last follow-up were identified, of whom 4 had no evidence of disease after more than 5 years follow-up.

OS after resection for LN+ PHC compared favorably with a 12 months median OS in patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy. Patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy were chosen, because of their relative comparability to the resected cohort. In contrast, median OS for non-operated patients has been reported as less than 6 months.(19) Explored non-resected patients were found to have vascular or biliary involvement precluding a complete resection with adequate liver remnant or had positive lymph nodes (N1 or N2). The difference of 7 months between the resected and the non-resected cohorts may be attributable to both the resection in the resection cohort and more advanced disease in the non-resected cohort. Therefore, the actual benefit of resection for LN+ PHC patients is likely smaller than 7 months.

The potential survival benefit of surgery must be weighed against the potential harm of surgery with a mortality of 5 to 15% in published Western series.(11, 12) A risk score by Wiggers et al. identified a high-risk subgroup of PHC patients with a 37% postoperative mortality risk based on age, preoperative cholangitis, future liver remnant, portal vein reconstruction, and incomplete drainage of the future liver remnant.(20)

Recent advances in imaging techniques have made it possible to identify lymph node metastases preoperatively with an acceptable accuracy, with a positive predictive value of 80% and a negative predictive value of 84% using computed tomography and a short axis diameter of 10 mm.(21, 22) EUS/FNA can confirm nodal metastases in suspicious lymph nodes on imaging. This is recommended in most patients for N2 nodes (beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament, stage IVb) because of poor prognosis after resection. Biopsy of N1 nodes should be considered in patients with a high postoperative mortality risk because of advanced age (>70 years), small future liver remnant (<30%), or preoperative cholangitis. When positive N2 nodes are found during exploratory laparotomy the surgeon should also consider to withhold resection. In addition, withholding resection can be considered in high-risk patients with positive N1 nodes during exploratory laparotomy; the small potential survival benefit of resection may not justify the risk of surgery.

In addition, LVI and positive resection margin were independent poor prognostic factors after resection of LN+ PHC. Both LVI and R1 resection have previously been identified as poor prognostic factors after PHC resection.(14, 23) Unfortunately, LVI and margin status are more difficult to guide decision making because they are typically known only after resection.

Patients in the resected cohort were much more likely to receive postoperative chemotherapy than in the non-resected cohort. The explanation for this difference is likely a combination of better postoperative performance status after resection and the willingness of both patients and physicians to administer adjuvant chemotherapy. This is contrary to phase III trials that support palliative chemotherapy more than adjuvant chemotherapy.(24, 25)

This study has several limitations. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the two cohorts differed in baseline tumor characteristics and the actual difference in OS between the resected and the non-resected cohort may be smaller than 7 months. Secondly, work-up and decision-making differed across centers and over time. Finally, because of the small sample size of N2 disease in the observed cohort, definitive conclusions could not be drawn in the present study. The preoperative decision to perform an exploratory laparotomy and the intraoperative decision to perform or withhold a resection are influenced by many known and unknown factors. However, the presented data from 12 centers may be some of the best available data to guide decision making for patients with LN+ PHC.

In conclusion, patients with PHC who underwent a resection for LN+ disease had better OS than patients who did not undergo resection because of locally advanced disease at exploratory laparotomy. The actual benefit of resection in patients with LN+ PHC may be smaller than 7 months and should be weighed against considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Proportional Hazards Regression Models in Patients with LN+ Disease Undergoing Resection.

| Variable Name | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95%CI | P-value | HR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Sex (male) | 1.01 | 0.66-1.55 | 0.959 | |||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.595 | |||

| BMI | 0.99 | 0.95-1.04 | 0.729 | |||

| Clinical Jaundice | 1.29 | 0.70-2.38 | 0.410 | |||

| ASA | ||||||

| I-II | Ref | - | - | |||

| III-IV | 0.90 | 0.50-1.62 | 0.731 | |||

| Drainage Preoperative | ||||||

| None | Ref | - | - | |||

| Endoscopic | 0.97 | 0.54-1.72 | 0.905 | |||

| Percutaneous | 1.52 | 0.79-2.90 | 0.208 | |||

| Both | 1.17 | 0.63-2.20 | 0.618 | |||

| Major Resection (≥3 segments) | 1.22 | 0.69-2.16 | 0.503 | |||

| Margin Status | ||||||

| R0 | Ref. | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| R1 | 1.48 | 0.96-2.27 | 0.075 | 1.54 | 0.97-2.45 | 0.067 |

| N2 Lymph Node metastases | 0.83 | 0.36-1.90 | 0.653 | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 1.00 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.804 | |||

| Bismuth Classification | ||||||

| I | Ref. | - | - | |||

| II | 0.56 | 0.17-1.82 | 0.332 | |||

| IIIA | 1.13 | 0.40-3.25 | 0.816 | |||

| IIIB | 0.91 | 0.31-2.68 | 0.862 | |||

| IV | 0.94 | 0.33-2.69 | 0.906 | |||

| AJCC T-stage | ||||||

| T1-T2 | Ref. | - | - | |||

| T3-T4 | 1.45 | 0.78-2.67 | 0.238 | |||

| Lymphovascular Invasion | 1.64 | 1.05-2.58 | 0.030 | 1.71 | 1.09-2.69 | 0.019 |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 1.08 | 0.70-1.66 | 0.725 | |||

| Adjuvant Radiotherapy | 1.04 | 0.67-1.63 | 0.856 | |||

Acknowledgments

Stefan Buettner was supported by the Van Walree Grant of the The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

Footnotes

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association Annual Meeting, March 29 – April 3, 2017, Miami, United States of America.

Funds/conflict of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hartog H, Ijzermans JN, van Gulik TM, Groot Koerkamp B. Resection of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96(2):247–67. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groot Koerkamp B, Fong Y. Outcomes in biliary malignancy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(5):585–91. doi: 10.1002/jso.23762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarnagin W, Winston C. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: diagnosis and staging. HPB (Oxford) 2005;7(4):244–51. doi: 10.1080/13651820500372533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichlmayr R, Lamesch P, Weimann A, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment of cholangiocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 1995;19(1):83–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00316984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo K, Rocha FG, Ito K, D’Angelica MI, Allen PJ, Fong Y, et al. The Blumgart preoperative staging system for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of resectability and outcomes in 380 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(3):343–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groot Koerkamp B, Wiggers JK, Allen PJ, Busch OR, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer staging for resected perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a comparison of the 6th and 7th editions. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16(12):1074–82. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igami T, Nishio H, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Nimura Y, et al. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the “new era”: the Nagoya University experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17(4):449–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodson RM, Weiss MJ, Cosgrove D, Herman JM, Kamel I, Anders R, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: management options and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(4):736–50 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brito AF, Abrantes AM, Encarnacao JC, Tralhao JG, Botelho MF. Cholangiocarcinoma: from molecular biology to treatment. Med Oncol. 2015;32(11):245. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2168–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas S, Sandroussi C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of vascular resection in the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15(7):492–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lafaro K, Buettner S, Maqsood H, Wagner D, Bagante F, Spolverato G, et al. Defining Post Hepatectomy Liver Insufficiency: Where do We stand? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(11):2079–92. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2872-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buettner S, van Vugt JL, Gani F, Groot Koerkamp B, Margonis GA, Ethun CG, et al. A Comparison of Prognostic Schemes for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3203-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groot Koerkamp B, Wiggers JK, Gonen M, Doussot A, Allen PJ, Besselink MG, et al. Survival after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma-development and external validation of a prognostic nomogram. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1930–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groot Koerkamp B, Wiggers JK, Allen PJ, Besselink MG, Blumgart LH, Busch OR, et al. Recurrence Rate and Pattern of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma after Curative Intent Resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(6):1041–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140(2):170–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaiteerakij R, Harmsen WS, Marrero CR, Aboelsoud MM, Ndzengue A, Kaiya J, et al. A new clinically based staging system for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(12):1881–90. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiggers JK, Groot Koerkamp B, Cieslak KP, Doussot A, van Klaveren D, Allen PJ, et al. Postoperative Mortality after Liver Resection for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Development of a Risk Score and Importance of Biliary Drainage of the Future Liver Remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(2):321–31 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HY, Kim SH, Lee JM, Kim SW, Jang JY, Han JK, et al. Preoperative assessment of resectability of hepatic hilar cholangiocarcinoma: combined CT and cholangiography with revised criteria. Radiology. 2006;239(1):113–21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelbrecht MR, Katz SS, van Gulik TM, Lameris JS, van Delden OM. Imaging of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(4):782–91. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soares KC, Kamel I, Cosgrove DP, Herman JM, Pawlik TM. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: diagnosis, treatment options, and management. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3(1):18–34. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.02.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein A, Arnold D, Bridgewater J, Goldstein D, Jensen LH, Klümpen H-J, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared to observation after curative intent resection of cholangiocarcinoma and muscle invasive gallbladder carcinoma (ACTICCA-1 trial) - a randomized, multidisciplinary, multinational phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):564. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1273–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]