Abstract

Background

The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends that adults accumulate moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in bouts of ≥10 minutes for substantial health benefits. To what extent the same amount of MVPA accumulated in bouts versus sporadically reduces mortality risk remains unclear.

Methods and Results

We analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006 and death records available through 2011 (follow‐up period of ≈6.6 years; 700 deaths) to examine the associations between objectively measured physical activity accumulated with and without a bout criteria and all‐cause mortality in a representative sample of US adults 40 years and older (n=4840). Physical activity data were processed to generate minutes per day of total and bouted MVPA. Bouted MVPA was defined as MVPA accumulated in bouts of a minimum duration of either 5 or 10 minutes allowing for 1‐ to 2‐minute interruptions. Hazard ratios for all‐cause mortality associated with total and bouted MVPA were similar and ranged from 0.24 for the third quartile of total to 0.44 for the second quartile of 10‐minute bouts. The examination of jointly classified quartiles of total MVPA and tertiles of proportion of bouted activity revealed that greater amounts of bouted MVPA did not result in additional risk reductions for mortality.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence that mortality risk reductions associated with MVPA are independent of how activity is accumulated and can impact the development of physical activity guidelines and inform clinical practice.

Keywords: accelerometer, activity bouts, adults, epidemiology, exercise, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Exercise, Primary Prevention

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This study examines whether moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity needs to be accumulated in bouts to provide mortality benefits.

Accelerometer‐measured physical activity data collected in 2003–2006 from a representative sample of US adults (n=4840) were classified as being accumulated sporadically or in bouts and linked to mortality records available through 2011.

Sporadic and bouted moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity was similarly and strongly associated with mortality risk.

Mortality risk reductions associated with moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity are independent of how activity is accumulated.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

This finding can inform future physical activity guidelines and guide clinical practice when advising individuals about the benefits of physical activity.

The key message based on the results presented is that total physical activity (ie, of any bout duration) provides important health benefits.

Practitioners can promote either long single or multiple shorter bouts of activity in advising adults how to progress toward 150 min/wk of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity.

This flexibility may be particularly valuable for individuals who are among the least active and likely at greater risk for developing chronic conditions.

The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends that adults accumulate at least 150 min/wk of moderate or 75 min/wk of vigorous‐intensity physical activity for substantial health benefits.1 The guidelines also direct that activity be performed in bouts of at least 10 minutes. The 10‐minute bout criterion originated in 1995 and was intended to provide flexibility in achieving the recommended dose.2 This messaging shift emphasized the importance of accumulating a total volume of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and has remained a central feature of guidelines as they evolved. Surprisingly, evidence supporting a minimum bout of 10 minutes is limited.3 Recent studies comparing MVPA accumulated in bouts to total minutes regardless of bouts suggest that bouts provide no additional benefit regarding metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, and body mass index.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, these studies are limited to cross‐sectional designs that evaluated risk factors, making it difficult to understand the temporal sequence for the observed associations or the influence of MVPA bouts on end points, such as all‐cause mortality. Thus, whether only bouts or total accumulated MVPA is more beneficial to mortality remains uncertain.

Methods

Study Population

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. Study data are from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) 2003–2006 cycles. NHANES samples noninstitutionalized US civilians using a multistage probability sampling design that considers geographical area and minority representation. Sample weights are generated to create nationally representative estimates for the US population and subgroups defined by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. See https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm for more details on NHANES sampling procedures. NHANES collects data on various health and behavior indicators, including physical activity and self‐reported diagnosis of prevalent health conditions such as diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, and cancer. These data were merged with mortality records from the National Death Index, available through December 2011. The National Center for Health Statistics links mortality records available through the National Death Index with individuals in the respective NHANES database using various individual information such as social security number, first name, month of birth, sex, race, and others.9 The matching process/linkage provides vital status for each individual that has been shown to accurately identify 87% to 97% of the true death records and is fairly accurate across race/ethnicities.10, 11, 12 Our study used linked mortality NHANES data released to the public by the National Center for Health Statistics and restricted the analytical sample to adults aged 40 years and older with complete data on all variables of interest (N=4840 respondents). Details of this cohort have been reported elsewhere.13 The NHANES study was reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board and all participants provided signed consent for participation.

Assessment of Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured with a waist‐worn uniaxial accelerometer (AM‐7164; ActiGraph) for up to 7 days using a standardized protocol.14 Data were initially screened for nonwear time using a previously developed algorithm for NHANES accelerometer data.14 Days with fewer than 10 hours of wear time were excluded and participants with at least 1 valid day of accelerometer data were included in the analysis. A threshold of 760 counts per minute defined MVPA. This threshold was defined to capture a broader range of lifestyle and ambulatory activities and has been demonstrated to provide accurate estimates of time spent in MVPA.15, 16, 17 Minutes of activity were computed for 3 measures of MVPA: total with no bout restriction, accumulated in ≥5‐minute bouts, and accumulated in ≥10‐minute bouts. MVPA accumulated in bouts of 5 or 10 minutes allowed for 1 and 2 minutes, respectively, of activity counts <760 counts per minute to accommodate real‐life activity patterns (eg, stopping at a crosswalk while walking).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with Cox proportional hazard models using established covariates of the physical activity–mortality association13: age (years), sex, race‐ethnicity (non‐Hispanic white, non‐Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), education (less than high school, high school diploma, high school or more), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), smoking status (never, former, current), body mass index (<25, 25–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2), and self‐reported diagnosis (yes/no) of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and mobility limitation.

First, we examined mortality associations by quartiles for each of the 3 MVPA measures: total, ≥5‐minute, and ≥10‐minute bouts, not accounting for differences in activity volume. Total MVPA was similar across the 3 measures and strongly correlated (r=0.7–0.9) (Table S1), suggesting that the measures were not independent and that individuals who accumulated the most total MVPA also accumulated high amounts of MVPA in 5‐ or 10‐minute bouts.

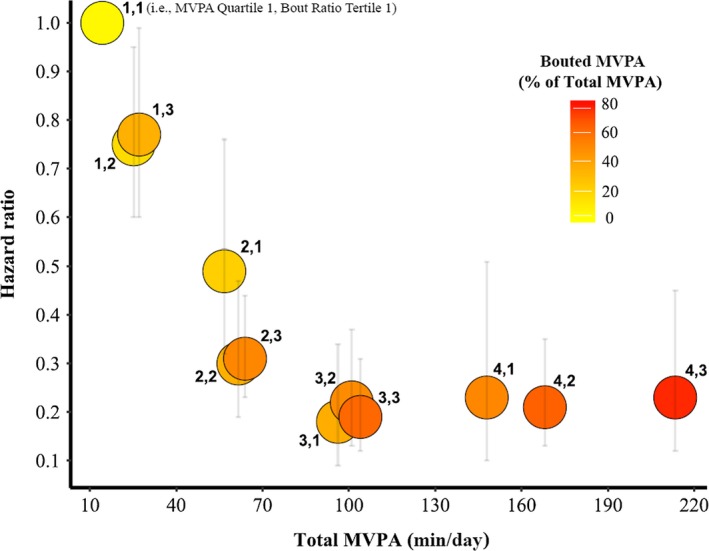

To account for the dependence between total and bouted activity, we jointly classified quartiles of total MVPA by bouted activity, based on tertiles of the proportion of total MVPA accumulated in bouts of ≥5 or ≥10 minutes. This resulted in 12 categories of total MVPA and relative contribution of bouted MVPA. Many participants, particularly in the lower quartiles of total MVPA, had 0 bouts of ≥10 minutes. This led to unstable estimates, so analyses focused on bouts of ≥5 minutes. In these analyses, evidence of greater benefit for bouted activity would be demonstrated by lower hazard ratios (HRs) as contribution of bouts to total MVPA increased. To further describe the relationship between these exposures we plotted the risk estimates for each of the 12 categories against total MVPA. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested and held true for our MVPA exposure. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design in NHANES and were conducted using the SAS version 9.3 (SAS Insistute Inc) and SUDAAN (RTI International) statistical packages.

Results

Over a mean follow‐up of 6.6 years, 700 deaths were recorded. Participants were 46.7% male and 77.4% non‐Hispanic white, 17.4% had less than a high school education, 21.1% were current smokers, and 62.0% reported drinking alcohol.

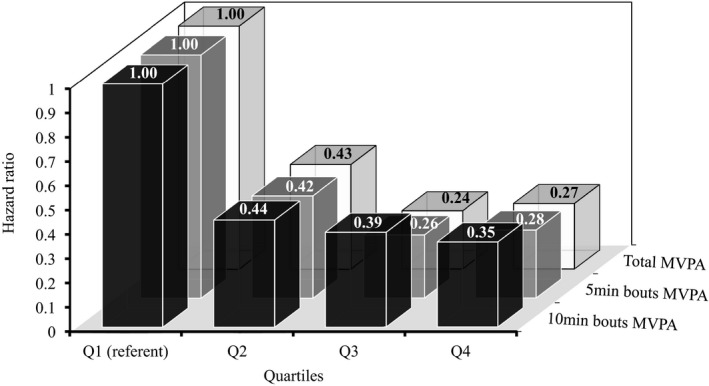

For each of the 3 MVPA measures, greater MVPA was associated with lower mortality (P trend <0.01; Figure 1). HRs ranged from 0.24 to 0.44 and were nearly identical for each measure. For example, risk was similar in the upper quartiles for total MVPA (HR, 0.27; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.45), 5‐minute bouts (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.17–0.45), and 10‐minute bouts (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.23–0.53) (Table S2). Among the categories jointly classified by quartiles of total MVPA and tertiles of bouted MVPA, greater total MVPA was associated with lower mortality, but greater proportions of bouted MVPA showed no additional risk reduction (Table). Specifically, within a given quartile of MVPA, HRs were similar across tertiles of bout proportion (Table, columns 2–4). For example, in the first MVPA quartile, higher contributions of bouted activity resulted in similar HRs for moderate (0.75; 95% CI, 0.60–0.95) and high amounts of bouted activity (0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.99). HRs across tertiles within each of the remaining quartiles were also similar. Analyses replicated with bouts of ≥10 minutes were unstable in the lowest 2 quartiles because >30% of the sample had no ≥10‐minute bouts, but showed the same pattern for quartiles 3 and 4 (data not shown). To visualize these relationships, we plotted the HRs for each of the 12 categories by total MVPA in each category (Figure 2). Overall, greater total MVPA was associated with lower mortality, reaching a plateau at about 100 min/d, with no appreciable additional benefit of greater relative contributions of bouted activity. It was also evident that accumulating greater total MVPA required continuous bouts of activity.

Figure 1.

Main effects for quartile‐specific distributions of total minutes per day of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and both ≥5‐ and ≥10‐minute bouts of accumulated minutes per day of MVPA. Quartiles: total MVPA (≤40.2, 40.2–79.5, 79.5–123.4, and >123.4 min/d); 5‐minute bouts MVPA (≤10.7, 10.7–34.3, 34.3–70.7, and >70.7 min/d); 10‐minute bouts MVPA (0.0, 0.0–5.1, 5.1–20.5, >20.5 min/d). Hazard ratios are adjusted for age, sex, race‐ethnicity, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, body mass index, and self‐reported diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and mobility limitation.

Table 1.

Mortality HRs for Joint Effects of Total MVPA and Proportions of Bouted (≥5 Minutes) MVPA

| Total MVPA | Less Bouted | Bout Ratioa | More Bouted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Tertile 1 | Tertile 2 | Tertile 3 |

| MVPA ≤40.2 min/d | Bouted ≤9% | 9% <Bouted ≤22.4% | Bouted >22.4% |

| No. | 392 | 392 | 393 |

| Deaths | 172 | 123 | 137 |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.75 (0.60–0.95) | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| Sporadic MVPA, min/d | 13.9±0.5 | 21.3±0.6 | 17.4±0.3 |

| Bouted MVPA, min/d | 0.4±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 9.8±0.3 |

| Total MVPA, min/d | 14.3±0.6 | 25.2±0.7 | 27.1±0.5 |

| Quartile 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 40.2<MVPA ≤79.5 min/d | Bouted ≤30.3% | 30.3% <Bouted ≤42.6% | Bouted >42.6% |

| No. | 408 | 408 | 409 |

| Deaths | 52 | 41 | 56 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.49 (0.32–0.76) | 0.30 (0.19–0.47) | 0.31 (0.23–0.44) |

| Sporadic MVPA, min/d | 44.2±0.5 | 39.4±0.3 | 30.2±0.4 |

| Bouted MVPA, min/d | 12.6±0.3 | 22.3±0.3 | 34.0±0.4 |

| Total MVPA, min/d | 56.7±0.6 | 61.6±0.6 | 63.9±0.6 |

| Quartile 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 79.5<MVPA ≤123.4 min/d | Bouted ≤45.3% | 45.3% <Bouted ≤56.2% | Bouted >56.2% |

| No. | 409 | 409 | 410 |

| Deaths | 15 | 20 | 28 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.18 (0.09–0.34) | 0.22 (0.13–0.37) | 0.19 (0.12–0.31) |

| Sporadic MVPA, min/d | 60.6±0.6 | 50.4±0.3 | 38.6±0.5 |

| Bouted MVPA, min/d | 35.6±0.5 | 51.1±0.4 | 66.4±0.5 |

| Total MVPA, min/d | 96.2±0.7 | 101.0±0.7 | 104.2±0.6 |

| Quartile 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MVPA >123.4 min/d | Bouted ≤61.1% | 61.1% <Bouted ≤71.9% | Bouted >71.9% |

| No. | 401 | 402 | 403 |

| Deaths | 17 | 19 | 18 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.23 (0.10–0.51) | 0.21 (0.13–0.35) | 0.23 (0.12–0.45) |

| Sporadic MVPA, min/d | 69.7±0.7 | 57.9±0.5 | 44.4±1.0 |

| Bouted MVPA, min/d | 78.8±1.3 | 111.8±1.1 | 172.8±4.0 |

| Total MVPA, min/d | 147.9±1.7 | 168.1±1.3 | 213.4±3.8 |

CI indicates confidence interval.

Computed as (minutes per day of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity [MVPA] in ≥5‐minute bouts per total minutes per day of MVPA)×100. Sum of sporadic and bouted MVPA may exceed total MVPA due to allowance for minutes below threshold in bouts. Hazard ratios (HRs) are adjusted for age, sex, race‐ethnicity, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, body mass index, and self‐reported diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and mobility limitation.

Figure 2.

Distribution of hazard ratios provided in the Table by total duration of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for jointly classified quartiles of total minutes and tertiles of relative contribution of bouted minutes. For example, 4,1 is equivalent to combined quartile 4 of total MVPA and tertile 1 (Table) of the relative contribution of bouted to total minutes. The relative contribution (%) of bouted MVPA minutes ranged from 3% (bright yellow) to 81% (dark red). The joint group 4,1 represents 150 minutes in total MVPA and ≈50% of the total duration was accumulated in bouts of ≥5 minutes. The remaining 50% was accumulated in sporadic activity. The grey error bars indicate the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals for respective hazard ratios. Hazard ratios are adjusted for age, sex, race‐ethnicity, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, body mass index, and self‐reported diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and mobility limitation.

Discussion

This prospective study examined the relative benefits of bouted versus sporadic MVPA on mortality in a representative sample of US adults, using an objective measure of physical activity. Greater total MVPA was strongly associated with lower mortality, and bouted activity conferred little additional benefit. Thus, these results provide evidence that mortality risk reductions associated with MVPA are independent of how activity is accumulated. These results can inform the development of the second edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and other recommendations.

Several published studies have examined the associations between physical activity and mortality and were used to inform the current physical activity guidelines.3 However, most of these studies relied on data obtained from self‐reports and only a few explored these associations using device‐based measures of physical activity.13, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Even though the current physical activity guidelines recommend that activity be accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes, most of these studies also examined the relative benefits of sporadic MVPA. The few studies specifically examining the value of bouted physical activity showed that sporadic versus bouted activity had similar associations with the metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, and body mass index.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, all of these studies employed cross‐sectional designs and examined intermediate end points. Thus, these studies could not address the ancillary question of whether sporadic and bouted activity can provide similar health benefits. In our study, similar to earlier published NHANES studies, we found risk reductions for all‐cause mortality to range from 60% to 80% across increased amounts of accumulated sporadic MVPA. However, the key finding of our study was that lowered risk for all‐cause mortality associated with sporadic MVPA was no different than the lowered risk associated with activity accumulated in bouts of ≥5 minutes. This finding aligns with previous studies examining cross‐sectional associations of sporadic versus bouted activity with various health risk factors; however, it provides new evidence that benefits for mortality, a robust health end point, are independent of how activity is accumulated.

Our study is the first to use data from a representative sample of US adults with device‐based estimates of physical activity to compare the benefits of sporadic with bouted activity. Our analyses provide a robust estimate of such benefits but include a few challenges that are worth mentioning. We found that total and bouted activity were highly correlated (r=0.7–0.9) and that few individuals in the United States accumulate activity in bouts of ≥10 minutes (>30% of the sample had no 10‐minute bouts detected). These preliminary findings shaped our efforts in modeling the associations among sporadic versus bouted activity and mortality. To address these challenges, we jointly classified quartiles of total MVPA at various contributions of bouted activity of ≥5 minutes. We were unable to fully analyze the effects of MVPA accumulated in bouts of ≥10 minutes; however, where data were available, results for 5‐ and 10‐minute bouts were similar. We also recognize that a variety of published cut points are available to define MVPA intensity.18 NHANES studies have commonly employed 2020 counts per minute, which is based on ambulatory calibration, to define MVPA; however, we chose to use a cut point calibrated to capture a greater variety of lifestyle activities in addition to ambulatory movement. Our selected cut point has been extensively evaluated and demonstrated to provide valuable insights when examining the associations between physical activity and mortality.13, 15, 16, 17, 23 We explored the use of the ambulatory MVPA threshold (ie, 2020 counts per minute) in our study but found limited utility as the majority of our sample did not accumulate any MVPA in bouts of 10 minutes with this threshold. We previously examined the associations of sporadic activity using either 760 or 2020 counts per minute and found similar associations with mortality (unpublished findings). Thus, we do not expect our conclusions to be dependent on our choice of the 760 cut point, and consider that the magnitude of our associations for both sporadic and bouted activity may be conservative.

Conclusions

Despite the historical notion that physical activity needs to be performed for a minimum duration to elicit meaningful health benefits, we provide novel evidence that sporadic and bouted MVPA are similarly associated with substantially reduced mortality. This finding can inform future physical activity guidelines and guide clinical practice when advising individuals about the benefits of physical activity. Practitioners can promote either long single or multiple shorter episodes of activity in advising adults on how to progress toward 150 min/wk of MVPA. This flexibility may be particularly valuable for individuals who are among the least active and likely at greater risk for developing chronic conditions.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Weighted US Adult Distributions of Total Time Per Day Spent in Sedentary, Light, and MVPA Across Quartiles of Total and Bouted MVPA

Table S2. HRs for Quartiles of Total and 5‐ and 10‐Minute Bouted MVPA

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007678 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007678.)29567764

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services . Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008. Available at: http://www.health.gov/PAGuidelines. Accessed August 16, 2017.

- 2. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, Ettinger W, Heath GW, King AC, Kriska A, Leon AS, Marcus BH, Morris J, Paffenberger RS, Patrick K, Pollock ML, Rippe JM, Sallis J, Wilmore JH. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robson J, Janssen I. Intensity of bouted and sporadic physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in adults. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jefferis BJ, Parsons TJ, Sartini C, Ash S, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG, Lee IM, Whincup PH. Does duration of physical activity bouts matter for adiposity and metabolic syndrome? A cross‐sectional study of older British men. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glazer NL, Lyass A, Esliger DW, Blease SJ, Freedson PS, Massaro JM, Murabito JM, Vasan RS. Sustained and shorter bouts of physical activity are related to cardiovascular health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strath SJ, Holleman RG, Ronis DL, Swartz AM, Richardson CR. Objective physical activity accumulation in bouts and nonbouts and relation to markers of obesity in US adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clarke J, Janssen I. Sporadic and bouted physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Center for Health Statistics . Office of Analysis and Epidemiology, NCHS 2011 Linked Mortality Files Matching Methodology, September, 2013. Hyattsville, MD: Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/2011_linked_mortality_file_matching_methodology.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arias E, Heron M; National Center for Health Statistics , Hakes J; US Census Bureau . The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat. 2016;2:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat. 2008;2:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matthews CE, Keadle SK, Troiano RP, Kahle L, Koster A, Brychta R, Van Domelen D, Caserotti P, Chen KY, Harris TB, Berrigan D. Accelerometer‐measured dose‐response for physical activity, sedentary time, and mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1424–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matthew CE. Calibration of accelerometer output for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S512–S522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crouter SE, DellaValle DM, Haas JD, Frongillo EA, Bassett DR. Validity of ActiGraph 2‐regression model, Matthews cut‐points, and NHANES cut‐points for assessing free‐living physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:504–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Welk GJ, McClain JJ, Eisenmann JC, Wickel EE. Field validation of the MTI Actigraph and BodyMedia armband monitor using the IDEEA monitor. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:918–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmid D, Ricci C, Leitzmann MF. Associations of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time with all‐cause mortality in US adults: the NHANES study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bakrania K, Edwardson CL, Khunti K, Henson J, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Davies MJ, Yates T. Associations of objectively measured moderate‐to‐vigorous‐intensity physical activity and sedentary time with all‐cause mortality in a population of adults at high risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Borgundvaag E, Janssen I. Objectively measured physical activity and mortality risk among American adults. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:e25–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loprinzi PD, Loenneke JP, Ahmed HM, Blaha MJ. Joint effects of objectively‐measured sedentary time and physical activity on all‐cause mortality. Prev Med. 2016;90:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fishman EI, Steeves JA, Zipunnikov V, Koster A, Berrigan D, Harris TA, Murphy R. Association between objectively measured physical activity and mortality in NHANES. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:1303–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evenson KR, Wen F, Herring AH. Associations of accelerometry‐assessed and self‐reported physical activity and sedentary behavior with all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:621–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Weighted US Adult Distributions of Total Time Per Day Spent in Sedentary, Light, and MVPA Across Quartiles of Total and Bouted MVPA

Table S2. HRs for Quartiles of Total and 5‐ and 10‐Minute Bouted MVPA