Abstract

Aims

The primary aim is to provide detailed rationale and methodology for the development and implementation of a perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise research protocol for women who self-chose surgical intervention and who may or may not have been offered behavioral treatments initially. This protocol is part of the ESTEEM trial (Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced with Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence Trial) which was designed to determine the effect of a combined surgical and perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention versus surgery alone on improving mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) and overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms.

Methods

As part of a multi-site, prospective, randomized trial of women with MUI electing midurethral sling (MUS) surgical treatment, participants were randomized to a standardized perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention + MUS versus MUS alone. The specific behavioral intervention included: education on voiding habits, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), bladder training (BT), strategies to control urgency and reduce/prevent urinary symptoms, and monitoring/promoting adherence to behavioral recommendations. To ensure consistency across all eight research sites in the pelvic floor disorders network (PFDN), selective behavioral treatments sessions were audiotaped and audited for protocol adherence.

Results

The behavioral intervention protocol includes individualization of interventions using an algorithm based on pelvic floor muscle (PFM) assessment, participant symptoms, and findings from the study visits. We present, here, the specific perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise interventions administered by study interventionists.

Conclusions

This paper details a perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention research study protocol developed for women undergoing surgery for MUI.

Keywords: bladder training, female, pelvic floor exercise training, stress strategies, urge control strategies, urinary incontinence

1 INTRODUCTION

Mixed urinary incontinence is a complex, and challenging condition for patients, clinicians, and researchers as interventions directed to improve one symptom may not improve or may actually worsen another. Behavioral treatments, specifically bladder training (BT) and pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), are the mainstay of conservative management for MUI as they are effective, essentially risk free, and recommended as first-line therapy by several guidelines and consensus panels.1–4 Although most women with urinary incontinence (UI) and OAB receive behavioral intervention in combination with drug therapy, many become frustrated with performing exercises or cannot tolerate medication side-effects. Consequently, women with MUI will elect anti-incontinence surgery for an expected better outcome.

Some experts believe that women with MUI should not undergo stress UI (SUI) surgery due to potential risk of worsening OAB symptoms of urgency and frequency. Recently, MUS has been found to be highly effective with SUI cure rates up to 80% at 1 year5 with improvement in OAB outcomes in some women.5–9 Unfortunately, predicting which women may experience improvement or worsening of their OAB including urgency UI (UUI) after surgery, or how to best optimize MUS outcomes in this population remains unclear as behavioral treatment programs are often not published or compared.

1.1 Theoretical basis for ESTEEM behavioral treatment program model

The 5th International Consultation on Incontinence Committee on Adult Conservative Treatment recommends that clinicians provide the most intensively supervised (by a trained clinician) PFMT and BT intervention possible, as health care professional supervised programs generate better outcomes.2 There remains a need to investigate a supervised PFMT program derived from sound exercise science, including confirmation of a correct voluntary PFM contraction and incorporation of appropriate supervision and adherence measures to promote maintenance of knowledge acquisition.10 Also, little is known regarding a structured algorithm model of delivering UI behavioral interventions.2 This paper’s aim is to provide detailed rationale and methodology for the development and implementation of a combined conservative (behavioral intervention [PFMT with BT]) and surgical treatment protocol for women with MUI, including training of study interventionists to deliver interventions in a standardized manner.

1.2 ESTEEM methods summary

The ESTEEM trial was designed to compare a combined conservative and surgical treatment approach versus surgery alone for improving patient-centered MUI outcomes at 12 months. It is a multi-site, prospective randomized trial of female patients with MUI randomized to a standardized perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention plus MUS versus MUS alone.11 Sung and colleagues describe the inclusion and exclusion criteria and primary and secondary outcomes.11 At the end of the ESTEEM trial, we will understand whether a combined conservative/surgical treatment approach is superior to surgery alone for MUI.

1.3 Overview of the perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle exercise intervention

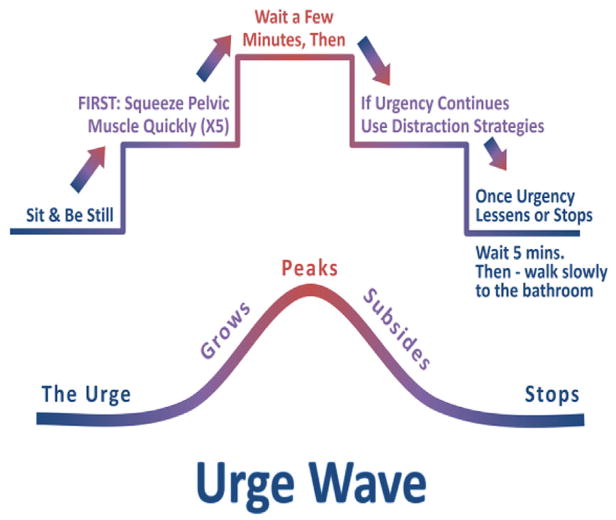

Over time, PFMT has evolved both as a nurse- and/or physical therapist-directed behavioral intervention for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).12 In women, it is postulated that a PFM contraction may raise and press the urethra towards the symphysis pubis, prevent urethral descent, and improve structural pelvic organ support.13 Intensive PFMT is hypothesized to induce muscle hypertrophy, increasing external mechanical pressure on the urethra; and reinforcing bladder neck support during increases in abdominal pressure.14,15 A PFMT program involves instruction on contracting and relaxing the PFMs correctly to improve muscle strength and coordination, and to functionally use these muscles (termed the “Knack” as in developing a knack to repeatedly do something/stress strategy) to occlude the urethra during physical activities that increase abdominal pressure and precipitate UI.16,17 Quick PFM contractions can be used to inhibit a bladder contraction at the time of urgency as a method of urge suppression.

Because the “best” PFMT program for MUI is unknown, the ESTEEM perioperative behavioral/PFM exercise intervention was developed based on sound consensus-based muscle training guidelines, BT instructional and motor learning principles and findings from the exercise adherence literature. A targeted number of exercise repetitions were based on the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for increasing muscle strength.18 Exercise volume recommendations to improve muscular fitness18 specifically 2–4 sets of resistive exercise/muscle group with 8–12 contraction repetitions/each set, were considered to be the prescribed ESTEEM exercise program of 45 PFM contractions per day (15 PFM contractions performed three times per day). This specific PFM exercise volume has been shown to be feasible with regard to exercise adherence and effective in improving urinary outcomes.19,20

An additional PFM exercise goal is to improve participant’s behavioral skills to prevent SUI and UUI across a variety of situations that trigger symptoms. To promote skill learning, we considered the impact of two important motor learning variables, augmented feedback, and transfer. Augmented feedback is information that supplements information an individual receives from their own sensory systems.21 During each study visit, the interventionist provides augmented verbal feedback to enhance participants’ ability to learn a correct PFM contraction. However, constant or high frequency feedback is detrimental to motor learning22 and may prevent the participant from developing the ability to self-assess their performance.23 To promote motor learning, the amount of feedback provided to participants is gradually decreased. To facilitate transfer22 of PFM exercise skill to new situations, the ESTEEM protocol includes specific PFM function criteria to advance body position (supine, sitting, and standing) for exercise.

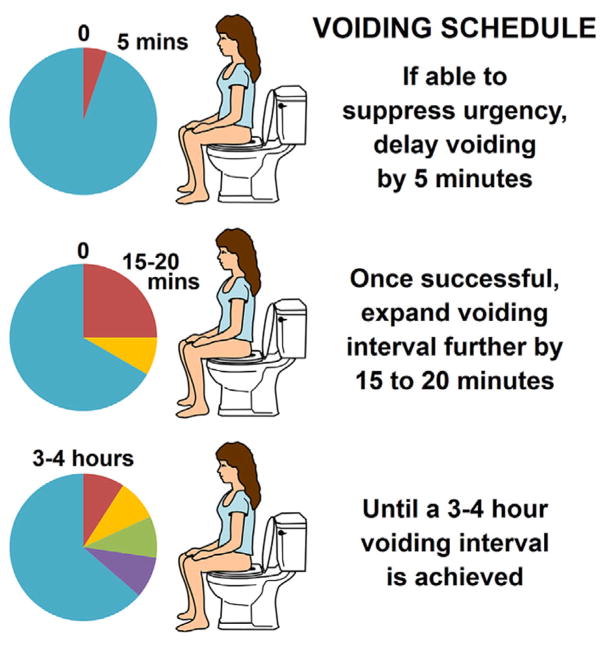

Bladder training has been advocated for management of urgency and frequency symptoms, since the late 1960s24 and as a treatment for female MUI and SUI.2,12,25,26 It is an intensive behavioral treatment that is recommended for highly motivated adult patients without cognitive or physical impairments.27,28 The goal of BT is to restore normal bladder function through a process of education along with a mandatory or self-adjustable voiding regimen that gradually increases the time interval between voids. Possible mechanisms for BT improving LUTS include: 1) improving central control over bladder sensations and urethral closure25,29 and/or 2) changing an individual’s behavior in ways that increase the LUT system’s “reserve capacity” as knowledge of circumstances that cause bladder leakage is gained.25,30 Many patients who experience urgency, with or without leakage, tend to void frequently to obtain immediate symptom relief. Unfortunately, this behavior may set the stage for more frequent urination, a habit that is difficult to change, and may lead to reduced functional bladder capacity, and in some cases, UUI. Bladder overactivity produces urgency, completing a cycle of urgency and frequency, that is, then, perpetuated.

Bladder training is a multi-component intervention that involves patient education regarding LUT function, setting incremental voiding schedules, and teaching urge control techniques to postpone voiding and adhere to a schedule.25,28,31,32 The effectiveness of behavioral training with urge suppression as a stand-alone strategy for UUI has been established in several clinical studies33–36 and in RCTs using intention-to-treat models, in which mean reductions of UI range from 60 to 80%.37,38 Research is inconclusive as to whether BT combined with urge suppression is effective alone versus BT with urge suppression combined with PFMT for continence or symptom improvement.

1.4 The ESTEEM progressive perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle exercise model

Our behavioral/PFM exercise protocol included individualized, progressive PFMT, and BT education, strategies to suppress urgency, extend voiding intervals, and prevent/reduce UI. Sites were required to have at least two trained, qualified interventionists (registered nurses, nurse practitioners, or physical therapists). To ensure standardization across sites, interventionists attended standardized training (see Table 1), including didactic lectures on LUT physiology/dysfunction; PFM anatomy, physiology, and exercise prescription/progression; use of a Bladder Diary for BT and delayed voiding; behavioral principles and strategies for urge suppression and preventing SUI; and ways to optimize exercise/behavioral adherence. Problem-oriented patient cases were also discussed. Lastly, certification in PFM digital examination; bladder diary interpretation; prescribing, teaching, and progressing PFM exercise and behavioral strategies; and promoting long-term exercise and behavioral strategy adherence were included. The Interventionist Manual of Treatment (IMOT) ensured standardization of the intervention. All interventionist sessions were audiotaped. Auditing of each interventionist occurred at least twice during the study to ensure intervention standardization and quality. Feedback was provided to all interventionists. If protocol drift was identified, additional auditing/feedback was provided until drift was resolved.

TABLE 1.

Standardization of training and protocols

| • Prior to centralized training, interventionists reviewed and were tested (80% correct responses required on all written tests to pass) on: |

| ○ The ESTEEM protocol. |

| ○ The Interventionist Manual of Treatment (IMOT). This manual was developed for ESTEEM and includes details of all procedures to be performed at each visit. It also defines situations that would be classified as a protocol deviation. |

| ○ E-learning modules (completion verified by data coordinating center). |

| ○ Bladder diary review, voiding interval calculations with online case modules. |

| • The IMOT includes detailed: |

| ○ PFM exercise progression and BT procedures based on study visit. |

| ○ Protocol for individualizing the PFM exercise progression or when “special circumstances” (ie, weak PFMs, inability to relax PFMs following a contraction) are encountered. |

| ○ Specific recommendations to promote adherence to PFM exercise and/or behavioral strategy recommendations when identified on the ESTEEM behavioral adherence questionnaire. |

| • During each intervention visit, a checklist of protocol elements is used by the interventionists to prevent protocol drift. |

| • Interventionists are required to use the Behavioral Skills and Treatment Booklet for participant education on the 4 behavioral components (PFM exercise, BT with urge suppression strategies, stress strategies, and healthy voiding habits); and when prescribing the specific PFM exercise progression, BT and voiding interval, behavioral strategies (urge suppression, “Knack” or “stress strategy,” and normal voiding techniques. |

| • Audiotaping of all intervention sessions with a subset audited by behavioral therapy experts to ensure protocol adherence. Protocol deviations will be addressed as necessary. |

| • Phone calls between interventionists and behavioral experts will take place as needed to ensure protocol adherence and to discuss interventionists concerns and/or questions as they arise. |

Because women with MUI struggle with BT and PFM exercise recommendations,20 an adherence questionnaire was administered to participants at each post-operative visit to monitor barriers to intervention adherence. This questionnaire was modeled after similar questionnaires administered to women with UI who participated in clinical trials that combined a behavioral intervention to other non-surgical interventions.20,39 The ESTEEM “Behavioral Skills and Treatment Booklet” was created to provide participants with standardized education and behavioral intervention instructions, to serve as a reference between study visits, and to reinforce long-term retention of specific intervention components At each visit, the specific PFM exercise, BT, behavioral strategy, and program adherence recommendations were recorded in the booklet.

1.5 Behavioral treatment intervention model

The overarching behavioral/PFM exercise intervention goals were to increase participant’s knowledge of bladder function, pelvic floor anatomy and function, and voiding habits. Integral to achieving study goals was the participant’s ability to perform a correct PFM contraction. Participants were expected to increase skill and independence in performance of PFM exercises, BT strategies (urge suppression to delay voiding, increase voiding intervals, and decrease urinary frequency), and PFM strategies to prevent SUI and control bladder urgency. Fluid intake modification, bowel symptoms/regimens, and/or dietary bladder irritants were not included to ensure study results are based on the effects of combined PFMT and BT alone.

At each visit, the interventionist performed a digital vaginal examination to determine the participant’s ability to consistently perform a correct (isolated, without Valsalva), sustained PFM contraction.40 During the baseline visit, feedback regarding a correct PFM exercise was provided to enhance skill performance. However, to promote motor learning and recognition of correct exercise, the amount of feedback provided within this session (and across future visits) was gradually decreased.

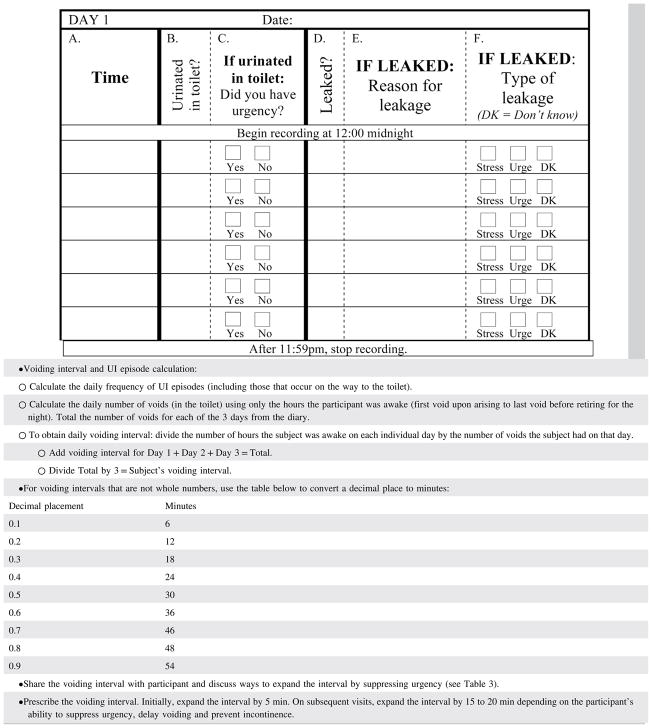

Participants recorded voids, presence of urgency and incontinence, reasons for incontinence, and incontinence pad use (total daily number, number of wet pads) on a 3-day Bladder Diary41 (see Table 2). The diary was used to monitor changes in voiding function and UI; explore reasons for incontinent episodes; calculate new voiding schedules; coach participants on reducing symptoms using the protocol appropriate behavioral strategy (see Table 3); and provide feedback of progress to participants.

TABLE 2.

Bladder diary instructions

Source: Sampselle, Newman, Miller, Translating Unique Learning for Incontinence Prevention: The TULIP Project, R01NR012011, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Health.

TABLE 3.

Instructions on bladder training, urge suppression, and voiding habits

|

1.6 Specifics of intervention visits

The ESTEEM behavioral intervention was delivered over a 6-month period, including a preoperative visit (2–4 weeks [wks] before surgery), a postoperative telephone call (2–4 days post-hospital discharge), and five postoperative visits (at 2-, 4-, 6-, and 8-wks, and 6-months).

1.6.1 Baseline preoperative visit

The visit began with education on: 1) genitourinary terminology, anatomy, function, and continence mechanisms; 2) correct PFM contraction; 3) BT using urge suppression techniques; and 4) use of the “Knack” or “stress strategy” to prevent SUI. To determine the individual’s preoperative home exercise prescription (HEP) and BT prescription, each person performed three blocks (sets) of 10 PFM contractions. In Block 1 (verification block), participants contracted/relaxed their PFMs for 1 s/2 s, avoiding forceful contractions to prevent fatigue, straining, and accessory muscle recruitment. In Block 2 (exercise block), participants contracted/relaxed their PFMs for 3 s/3 s. Interventionist feedback on PFM exercise technique, 1- to 2-min rest periods, and exercise modifications (see Table 4) were provided for those who could not or incorrectly contracted/relaxed their PFMs.

TABLE 4.

Home pelvic floor muscle exercise prescription criteria based on performance

| Visit | Performed ≥ 7/10 contractions without Valsalva or counterproductive muscle activity | Performed <7/10 contractions without Valsalva or counterproductive muscle activity | Performed contractions with Valsalva, counterproductive muscle activity OR unable to contract PFMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Baseline visit: 1–5 wks pre-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 3 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–3 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1 s |

|

|

|

|

| 2 2 wks post-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 1–3 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–3 s | Same as visit 1 |

|

|

||

| 3 4 wks post-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 1–5 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–5 s | Same as visit 1 |

|

|

||

| 4 6 wks post-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 1–7 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–7 s | Same as visit 1 |

|

|

||

| 5 8 wks post-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 1–9 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–9 s | Same as visit 1 |

|

|

||

| 6 6 months post-operative | Contraction duration criteria = 1–10 s | Contraction duration criteria = 1–9 s | Same as visit 1 |

|

|

Exception: if participant remains unable to demonstrate a palpable PFM contraction, advise to discontinue exercises. |

Block 3 served as a “retention block or test” to determine the pre-operative PFM HEP. To simulate independent practice conditions, no feedback or rest periods were permitted. The participant performed as many PFM contractions (up to 10) at the contraction/relaxation duration held consistently during Block 2. Pre-operative PFM exercise recommendations were based on the number of PFM contractions the participant performed correctly (maximum of 10). Table 4 lists standardized criteria for prescribing the PFM contraction/rest duration and exercise position progression per intervention visit. All participants were instructed to perform a maximum of 45 contractions per day (three sessions of 15 contractions).

Next, using the Behavioral Skills and Treatment Booklet, individualized education based on bladder diary results was provided to the participant to improve voiding habits and decrease LUTS using BT. Urge suppression using the PFMs was taught only if the participant demonstrated an isolated PFM contraction during the baseline examination.

1.6.2 Post-operative phone call

During this phone call, the interventionist determined the participant’s readiness to resume the behavioral intervention. Indwelling urinary catheter removal was required to resume PFM contractions. If a participant was experiencing pain and discomfort, PFM exercises were not resumed and the participant was instructed to use techniques (not PFM contractions) to suppress and control urgency (See Table 3). If no discomfort, the participant was instructed to restart the HEP 2–4 days, post-surgery and to use their PFMs to prevent SUI and/or suppress urgency.

1.6.3 Post-operative visits 2-, 4- 6- and 8-weeks

For each of these visits, the interventionist evaluated participants for changes in bladder symptoms and PFM function, and determined adherence and barriers to performing the prescribed interventions. Remediation and/or reinforcement in correct PFM exercise, BT, use of the “Knack/Stress” and urge suppression strategies was provided. Additionally, the interventionist modified/progressed the pre-operative prescribed HEP recommendations (See Table 5). If the participant denied urinary symptoms at these visits, the HEP was still administered per the protocol, and the importance of continuing the intervention to prevent recurrence of symptoms and to maintain integrity of the surgical repair was reinforced.

TABLE 5.

Modifications for specific circumstances and to promote exercise/behavioral adherence

| Specific circumstances | ||

|---|---|---|

| Circumstance | Prescription | Rationale |

| No palpable PFM contraction and/or no sensation of contraction. |

|

|

| Weak muscle/muscle fatigues quickly (holds PFM contraction ≤1 s during exam) |

|

|

| Having difficulty performing exercises |

|

|

| Holds breath during exercise |

|

|

| Bears down instead of contracting PFM |

|

|

| Contracts abdomen, buttocks, and/or hip adductors (accessory muscles) |

|

|

| Levator ani muscle not relaxed/increased stiffness or tightness when palpated |

|

|

| Barriers to exercise/strategy adherence | ||

| Barrier | Strategies to minimize barrier and improve adherence | |

| Difficult finding time to exercise/exercises take too much time |

|

|

| Forgets to do exercises |

|

|

| Not motivated to exercise |

|

|

| Not sure doing exercises correctly |

|

|

| Does not understand how to do strategy (urge or stress) or remember learning about strategy |

|

|

| Forgets to do strategy (urge or stress) |

|

|

| Tried strategy (urge or stress) but unsuccessful Not sure doing strategy (urge or stress) correctly |

|

|

| Do not think strategies (urge or stress) will help bladder symptoms. |

|

|

| Events like a cough, sneeze, and/or urgency come on too fast to do strategy. |

|

|

| Afraid to use urge suppression/delayed voiding for fear of bladder accident. |

|

|

The interventionist reviewed the participant’s prior week’s bladder diary41,42,43 to identify symptoms and progress. The interventionist also checked the Behavioral Adherence/Barrier Questionnaire (designed for this study) to obtain information regarding PFM exercise (volume, maximum contraction duration, body position, and exercise barriers) and behavioral strategy (effectiveness and strategy barriers) status and adherence. When a participant had no palpable PFM contraction, a weak PFM contraction, and/or identified barriers to exercise and/or behavioral strategies, the interventionist provided recommendations and modifications (see Table 4) to promote exercise/behavioral adherence. Recommendations were based on similar suggestions provided to participants in two multisite clinical trials19,44–46 that found ≥ 96% of women demonstrated a correct PFM contraction at the initial visit; ≥ 80% of participants performed at least 30 PFM contractions ≥ 5 days per week; and ≥ 87% were able to use stress/urge strategies to prevent urine loss and reduce urgency.20,39 Also, strategies for addressing barriers to physical activity adherence in women recommended by Huberty et al.47 were included in Table 5.

A home exercise prescription was based on the PFM examination/evaluation following similar procedures as the preoperative visit, except the participant performed only two blocks of 10 PFM contractions. For Block 1, correct PFM contraction/relaxation was verified and interventionist feedback and practice/exercise modifications were provided. Participants contracted their PFMs for the maximum duration they achieved post-operatively (maximum possible duration = 3 s at the 2-wk visit; and 5 and 7s, at the 4- and 6-wk visits, respectively) as reported on the Behavioral Adherence/Barrier Questionnaire. Block 2 (retention biock) served to determine the HEP (see Table 4). The subsequent 2-wk HEP included 45 PFM contractions/day, distributed across three exercise sessions.

At the 8-wk visit, participants that performed ≥ 7/10 PFM contractions correctly only performed Block 1. Those who did not achieve this goal, performed another set of 10 PFM contractions before the HEP was prescribed. By this visit, we expected most participants would demonstrate correct exercise allowing the interventionist to prescribe the new HEP following Block 1. The maximum possible contraction/rest duration achieved by a participant at 8-wks was 9 s (See Table 5).

It has been reported that women decrease PFM exercise over time.20 Therefore, a maintenance exercise frequency was provided at the 8-wk visit to promote long-term exercise adherence. Literature suggests that the exercise frequency required to preserve muscle strength is less than needed to initially build strength.48,49 One study of women with SUI found no differences in sustained improvements in urine loss, PFM strength, and quality of life at 6-months following a supervised PFM exercise program in those assigned to perform maintenance exercise once versus four-times per week.50 Maintenance exercise frequency was set to three times/wk; and exercise volume to 45 PFM contractions (as in prior visits) on the days exercises were performed.

At each post-operative visit, the interventionist educated the participant, using the diary results and the Behavioral Skills and Treatment Booklet, on healthy voiding habits, and BT emphasizing specific “urge suppression” and/or “stress” strategies to successfully decrease LUTS. The participant was instructed to use their PFMs to suppress urgency only if they demonstrated at least a trace, isolated muscle contraction during the examination.

1.6.4 Post-operative visit, 6-months

At this visit, the participant’s progress toward developing skill in performing PFM exercises and applying behavioral strategies to decrease bladder symptoms was determined. Final recommendations were prescribed. As per prior visit procedures, the interventionist examined and evaluated for changes in bladder symptoms and PFM function, determined adherence and barriers to performing PFM exercise and using behavioral strategies, and provided remediation and/or reinforcement in correct PFM exercise, BT, and use of the “Knack/Stress” and urge suppression strategies.

Like the 8-wk post-operative visit, only Block 1 needed to be performed to determine the PFM exercise prescription. At this visit only, participants that did not demonstrate a palpable PFM contraction upon examination were instructed to discontinue PFM exercises. The maximum possible contraction/rest duration achieved by 6-months was 10 s (See Table 4). Over the next 6-months, women were instructed to perform 45 PFM contractions, three-times per wk. Diary analysis with BT strategies were provided as needed. It is expected that by this visit, these strategies will have been incorporated into the participant’s daily voiding habit.

2 CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Most published research investigations that have studied the effectiveness of behavioral interventions to manage stress and/or UUI have not included detailed behavioral intervention methods and if standardization of interventions was maintained. Likewise, discussion of behavioral adherence barriers and strategies for improving adherence among such studies is rare. We addressed these issues by developing specific guidelines for ESTEEM study interventionists and publishing our methods. Within these specific guidelines, modifications for special circumstances were allowed to address participants that had poor PFM function and for those who struggled with behavioral treatment adherence. Study interventionists were required to attend standardized training and become certified on all elements of the ESTEEM behavioral protocol. An IMOT was developed to ensure standardization of the intervention. Finally, audits of interventionist sessions occurred to insure quality control of intervention delivery. By taking significant measures to detail and standardize the behavioral interventions, we expect to enhance our ability to measure the true impact of combining surgical and behavioral interventions to reduce LUTS in women with MUS. If positive study results are found, these methods can be used as the standard in future investigations that include behavioral interventions to improve bladder symptoms in women.

FIGURE 1.

Urge wave

FIGURE 2.

Voiding schedule

RESEARCH SITES.

The Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI.

The Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

The Division of Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Reproductive Medicine, UC San Diego Health System, San Diego, CA.

Women’s Center for Bladder and Pelvic Health, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pitts-burgh, PA.

Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia, PA.

Division of Urogynecology and Pelvic Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama.

Center for Urogynecology and Recnstructive Pelvic Surgery, Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women’s Health Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2U01HD41249, 2U10 HD41250, 2U10 HD41261, 2U10 HD41267, 1U10 HD54136, 1U10 HD54214, 1U10 HD54215, and 1U10 HD54241) and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health, Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01959347.

Funding information

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant numbers: 2U01HD41249, 2U10 HD41250, 2U10 HD41261, 2U10 HD41267, 1U10 HD54136, 1U10 HD54214, 1U10 HD54215, 1U10 HD54241; National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health, Grant number: NCT01959347

Abbreviations

- BT

bladder training

- ESTEEM

Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced with Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence Trial

- HEP

home exercise program

- IMOT

Interventionist Manual of Treatment

- LUTS

lower urinary tract symptoms

- MUI

mixed urinary incontinence

- MUS

mid-urethral sling

- OAB

overactive bladder

- PFDN

pelvic floor disorders network

- PFM

pelvic floor muscle

- PFMT

pelvic floor muscle training

- s

second

- SUI

stress urinary incontinence

- UI

urinary incontinence

- UUI

urgency urinary incontinence

- wk

week

Footnotes

ESTEEM PROTOCOL COMMITTEE

Diane Borello-France, PhD; Gena Dunivan, MD; Marie Gantz, PhD; Emily S. Lukacz, MD; Susan Meikle, MD, MSPH; Pamela Moalli, MD; Deborah L. Myers, MD; Diane K. Newman, DNP, ANP-BC; Holly Richter, PhD, MD; Beri Ridgeway, MD; Ariana L. Smith, MD; Alison Weidner, MD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

References

- 1.Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Shekelle P. Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):429–440. doi: 10.7326/M13-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore K, Bradley C, Burgio B, et al. Adult conservative treatment. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: Proceedings from the 5th International Consultation on Incontinence. Plymouth, UK: Health Publications; 2013. pp. 1101–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 Suppl):2455–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamliyan T, Wyman JF, Ramakrishnan R, Sainfort F, Kane RL. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Ann Intern Med. 2007;148(6):459–473. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609–617. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d055d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:923–932. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tahseen S, Reid P. Effect of Transobturator tape on overactive bladder symptoms and urge urinary incontinence in women with mixed urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):617–623. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819639e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611–621. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318162f22e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Risk factors associated with failure 1 year after retropubic or transobturator midurethral slings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(666):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20(1):CD005654. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung VW, Borello-France D, Dunivan G, et al. Methods for a multicenter randomized trial for mixed urinary incontinence: rationale and patient-centeredness of the ESTEEM trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(10):1479–1490. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3031-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman DK, Burgio KL. Conservative management of urinary incontinence: behavioral and pelvic floor therapy and urethral and pelvic devices. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 11. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 1875–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berghmans LC, Hendriks HJ, Bo K, et al. Conservative treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Urol. 1998;82:181–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLancey JO. Structural aspects of the extrinsic continence mechanism. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, but how does it work? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(2):76–84. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. A pelvic muscle precontraction can reduce cough-related urine loss in selected women with mild SUI. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:870–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J, Aston-Miller J, DeLancey J. The Knack: use of precisely-timed pelvic muscle contraction can reduce leakage in SUI. Neurourol Urodyn. 1996;15:302–393. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, Borello-France D, Corton M, Johnson HW. Urinary incontinence treatment network. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:161–169. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Goode PS, Markland AD, Kenton K, Balasubramanyam A. Adherence to behavioral interventions for urge incontinence when combined with drug therapy: adherence rates, barriers, and predictors. Phys Ther. 2010:1493–1505. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Motor Control: Translating Research Into Clinical Practice. 4. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winstein CJ, Schmidt RA. Reduced frequency of knowledge of results enhances motor skill learning. J Exp Psychol Learn Memory Cogn. 1990;16:677–691. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt RA, Kee TD. Motor Learning & Performance. From Principles to Application. 5. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2014. p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeffcoate TNA, Francis WJ. Urgency incontinence in the female. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;94:604–618. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(66)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fantl JA, Wyman JF, McClish DK, et al. Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. JAMA. 1991;265(5):609–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fantl JA, Newman DK, Colling J, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 2. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1996. Urinary incontinence in adults: acute and chronic management. 1996 Update, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadley ED. Bladder training and related therapies for urinary incontinence in older people. JAMA. 1986;18(256):372–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace SA, Roe B, Williams K, et al. Bladder training for urinary incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001308.pub2. Art. No. CD001308. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001308.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Fantl JA, Hurt WG, Dunn LJ. Detrusor instability syndrome: the use of bladder retraining drills with and without anticholinergics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140(8):885–890. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyman JF, Fantl JA, McClish DK, Bump RC. Comparative efficacy of behavioral interventions in the management of female urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wyman JF, Fantl JA. Bladder training in ambulatory care management of urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs. 1991;11:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Prac. 2009;63(8):1177–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baigis-Smith J, Smith DAJ, Rose M, Newman DK. Managing urinary incontinence in community-residing elderly persons. Gerontologist. 1989;29(2):229–233. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDowell BJ, Burgio KL, Dombrowski M, Locher JL, Rodriguez E. Interdisciplinary approach to the assessment and behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence in geriatric outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:370–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose MA, Baigis-Smith J, Smith D, Newman D. Behavioral management of urinary incontinence in homebound older adults. Home Health Nurse. 1990;8:10–15. doi: 10.1097/00004045-199009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgio KL, Whitehead WE, Engel BT. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. Bladder-sphincter biofeedback and toileting skills training. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(4):507–515. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al. Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2293–2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral versus drug treatment for urge incontinence in older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1998;23:1995–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Goode PS, et al. Adherence to behavioral interventions for stress incontinence: rates, barriers, and predictors. Phys Ther. 2013;93(6):757–773. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newman DK, Laycock J. Clinical evaluation of the pelvic floor muscles. In: Baessler K, Schussler B, Burgio KL, Stanton SL, editors. Pelvic Floor Re-Education: Principles and Practice. 2. London: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dmochowski RR, Sanders SW, Appell RA, Nitti VW, Davilla GW. Bladder-health diaries: an assessment of 3-day vs 7-day entries. Br J Urol Int. 2005;96(7):1049–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampselle CM. Teaching women to use a voiding diary. Am J Nurs. 2003;103(11):62–64. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200311000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyman JF, Choi SC, Harkins SW, Wilson MS, Fantl JA. The urinary diary in evaluation of incontinent women: a test-retest analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(6 Pt 1):812–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter HE, Burgio KL, Goode PS, et al. Non-surgical management of stress urinary incontinence: ambulatory treatments for leakage associated with stress (ATLAS) trial. Clin Trials. 2007;4:92–101. doi: 10.1177/1740774506075237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066–2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Design of the behavior enhances drug reduction of incontinence (BE-DRI) study. Contemp Clin Trial. 2007;28:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huberty JL, Ransdell LB, Sidman C, et al. Explaining long-term exercise adherence in women who complete a structured exercise program. Res Quart Exer Sport. 2008:374–384. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2008.10599501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carpenter D, Graves J, Pollock M, et al. Effect of 12 and 20 weeks of resistance training on lumbar extension torque production. Phys Ther. 1991;71:580–588. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.8.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graves J, Pollock M, Leggett S, Braith RW, Carpenter DM, Bishop LE. Effect of reduced training frequency on muscular strength. Int J Sports Med. 1988:316–318. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1025031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borello-France DF, Downey PA, Zyczynski HM, Rause CR. Continence and quality-of-life outcomes 6 months following an intensive pelvic-floor muscle exercise randomized trial comparing low- and high-frequency maintenance exercise. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1545–1553. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]