Abstract

Little is known about how chronic inflammation contributes to the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially the initiation of cancer. To uncover the critical transition from chronic inflammation to HCC and the molecular mechanisms at a network level, we analyzed the time-series proteomic data of woodchuck hepatitis virus/c-myc mice and age-matched wt-C57BL/6 mice using our dynamical network biomarker (DNB) model. DNB analysis indicated that the 5th month after birth of transgenic mice was the critical period of cancer initiation, just before the critical transition, which is consistent with clinical symptoms. Meanwhile, the DNB-associated network showed a drastic inversion of protein expression and coexpression levels before and after the critical transition. Two members of DNB, PLA2G6 and CYP2C44, along with their associated differentially expressed proteins, were found to induce dysfunction of arachidonic acid metabolism, further activate inflammatory responses through inflammatory mediator regulation of transient receptor potential channels, and finally lead to impairments of liver detoxification and malignant transition to cancer. As a c-Myc target, PLA2G6 positively correlated with c-Myc in expression, showing a trend from decreasing to increasing during carcinogenesis, with the minimal point at the critical transition or tipping point. Such trend of homologous PLA2G6 and c-Myc was also observed during human hepatocarcinogenesis, with the minimal point at high-grade dysplastic nodules (a stage just before the carcinogenesis). Our study implies that PLA2G6 might function as an oncogene like famous c-Myc during hepatocarcinogenesis, while downregulation of PLA2G6 and c-Myc could be a warning signal indicating imminent carcinogenesis.

Keywords: dynamical network biomarker, inflammation-induced HCC, critical transition, early diagnosis, high-grade dysplastic nodules, tipping point

Introduction

Recent studies have demonstrated that chronic inflammation contributes to development and progression of many cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Hussain and Harris, 2007; Mantovani et al., 2008; Diakos et al., 2014). On one hand, inflammation involves a well-coordinated response of an innate and adaptive immune system following infection or injury by endogenous or exogenous means (Hussain and Harris, 2007). On the other hand, a number of oncogenes, such as myc and ras, have been known to build up an inflammatory pro-tumorigenic microenvironment (Borrello et al., 2008). In particular, myc oncogene activation is observed most often in the pathogenesis of HCC (Beer et al., 2004). Meanwhile, HCC has been reported strongly associated with viral infections, e.g. hepatitis B especially in China (Farazi and DePinho, 2006; Jiang et al., 2012; Jhunjhunwala et al., 2014). Therefore, the interplay of both intrinsic (such as oncogene activation) and extrinsic (such as viral infection) factors is considered necessary for inflammation-associated HCC tumorigenesis.

One challenging goal is to reveal the underlying molecular mechanisms mediating initiation and progression of inflammation-associated carcinogenesis, which can be viewed as a nonlinear dynamical process with critical transition phenomena. We aim to elucidate the malignant transition and key mediating factors during the progression from chronic hepatitis to HCC at a system or network level, by using the dynamical network biomarker (DNB) theory and critical transition model. For this purpose, c-myc tumor-prone transgenic mice were infected with woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) to induce similar disease progression as hepatitis virus-associated HCC in humans (Etiemble et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2010), which combines both intrinsic (c-myc oncogene) and extrinsic (WHV infection) factors that cause inflammation-associated hepatocarcinorigenesis in a mouse model.

Statistical analyses based on big biological data or ‘Omics’ data have led to a number of important discoveries on pathological mechanisms, diagnoses, and treatments. However, most of current studies focus on static or molecular biomarkers, which mainly contribute to distinguishing different disease stages based on static characteristics, e.g. by using differentially expressed molecules (He et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Mitra et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015a; Liu et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2016). In other words, it is hard to catch unstable and dynamical signals happening at the critical period/stage, which are key information of the critical transition from inflammation to HCC. Here, we introduce our critical transition model with DNB method (Chen et al., 2012) to address this challenge. Compared with traditional biomarkers, DNB is able to identify the critical state or pre-disease state (just before the drastic transition to the disease state) during disease progression, based on ‘differential associations between molecules (differential networks)’ in a dynamical manner, and further to determine the corresponding functional network of the DNB. Another advantage of the DNB method is its model-free feature, which means a data-driven approach without requirements for parameters or even models.

In this study, we analyzed the time-series proteomic data of WHV/c-myc mice and age-matched wt-C57BL/6 mice, by using our phase transition model with DNB method, to identify the critical transition period from chronic inflammation to HCC and uncover the underlying molecular mechanisms at a network level.

Results

Dynamic proteomic data of WHV/c-myc transgenic mice and wt-C57BL/6 mice from inflammation to hepatocarcinogenesis

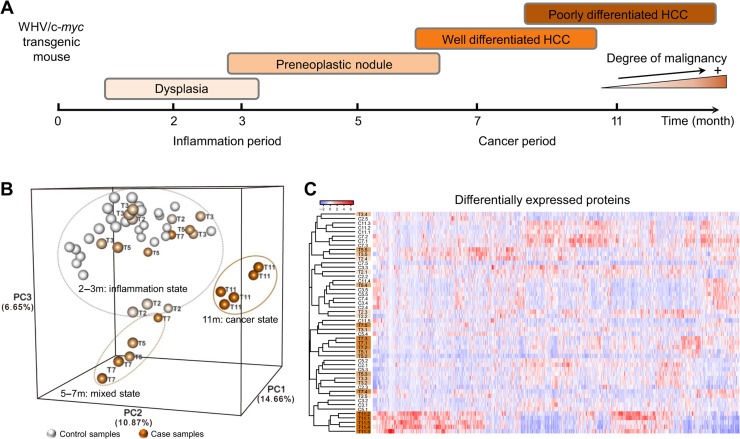

The WHV/c-myc transgenic mouse model shows a similar progression as hepatitis virus-associated HCC in humans, sequentially and simultaneously undergoing dysplasia, paraneoplastic nodule, adenomas, well differentiated HCC, poorly differentiated HCC, and finally high penetrance HCC (Figure 1A; Etiemble et al.,1994). Accordingly, we selected five different time points (i.e. 2, 3, 5, 7, and 11 months after birth) that basically match different stages of cancer initiation and development. Five WHV/c-myc mice (cases) and five wt-C57BL/6 mice (controls) were sacrificed at each time point, and liver tissues from a total of 25 cases and 25 controls were collected to analyze liver proteome at different states.

Figure 1.

The progression of hepatocellular carcinogenesis in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice and protein expression analyses. (A) A schematic diagram illustrates different pathophysiological symptoms of the liver during the progression of hepatocellular carcinogenesis in the WHV/c-myc transgenic mouse model. Liver tissue samples from 25 WHV/c-myc mice (cases) and 25 wt-C57BL/6 mice (controls), five mice per group at 2, 3, 5, 7, and 11 months after birth, respectively, were collected to measure protein expressions (Supplementary Figure S1). (B) PCA result shows sample clustering along disease progression based on 1465 DEPs. Each small spheroid represents the PC score along the top three principle components for each sample. Clearly, 25 case samples were clustered in three groups representing inflammation state, mixed state, and cancer state, respectively. Notably, T5 samples were not clustered together but scattered in two groups. One of T7 samples was also scattered in the inflammation state group. In contrast, 25 control samples were all clustered in the inflammation state group. (C) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering with PCC distance was performed to distinguish different stages based on 1465 DEPs. Similarly, T5 samples were not grouped together but scattered, implying that the 5th month after birth is different from other periods and is a key period from inflammation to HCC. C indicates a control sample (e.g. C2.3 is the 2-month-old control sample No.3) and T indicates a case sample (e.g. T7.4 is the 7-month-old case sample No.4).

Label-free quantified strategy combined with offline peptide fractionation and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) was applied on 50 mouse liver tissue samples (Supplementary Figure S1). We identified a total of 42689 distinct peptides among the 570 LC–MS/MS runs, corresponding to 2381085 spectra in an assembly of 8713 protein groups with a peptide-level false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.4%. Numbers of spectral counts, protein groups, and unique peptides at each time point for WHV/c-myc mice and wt-C57BL/6 mice were summarized in Supplementary Table S1. For the quantitative data, 3372 proteins with effective spectral counts and detected from >25 mice were considered (Supplementary Table S2). Then, we identified 1465 significantly differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) (Supplementary Table S2) and 3338 differentially co-expressed protein-pairs (DCEs) (Supplementary Table S3) by traditional biomarker analyses (Supplementary Figure S2A and B), which characterize disease-associated dysfunctions by evaluating the differences between case and control samples during hepatocellular carcinogenesis.

Then, we performed principle component analysis (PCA) (Figure 1B) and unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Figure 1C) based on the DEPs. The PCA result revealed that all mice were clustered into three relatively independent groups, i.e. (i) the cancer state group including all 11-month-old transgenic mice with cancer, (ii) the inflammation state group including transgenic mice (mainly 2−3 months) with inflammation but without cancer and all control (normal) mice, and (iii) the mixed state group including transgenic mice (5−7 months) at advanced inflammation or early HCC stage (Figure 1B). Clearly, 5-month-old transgenic mice (T5) were scattered in both inflammation state and mixed state groups, implying that they might be at the critical state before the malignant transition to HCC. Similarly, the hierarchical clustering result showed that 11-month-old transgenic mice (T11) became an independent group, while transgenic mice at 5−7 months (T5 and T7, in particular T5) were mixed with transgenic mice at 2−3 months and control mice with inflammation (Figure 1C). We also performed time course analysis to characterize different disease stages in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice (Supplementary Figure S3). All DEPs and DCEs were grouped for 16 different patterns according to their expression changing trends between two consecutive time points. These dynamic trends indicated differences between disease and normal mice, and also between different disease states. Notably, transgenic mice drastically deteriorated to a serious disease state at later time points, which might result from significant changes in most of DEPs and DCEs from 7 to 11 months. Hence, we supposed the existence of a critical period just before cancer initiation in transgenic mice at the age of 5−7 months; however, more details of this period cannot be characterized by the traditional analysis of differential expressions.

DNB analysis identifies the critical period or phase transition from chronic inflammation to HCC

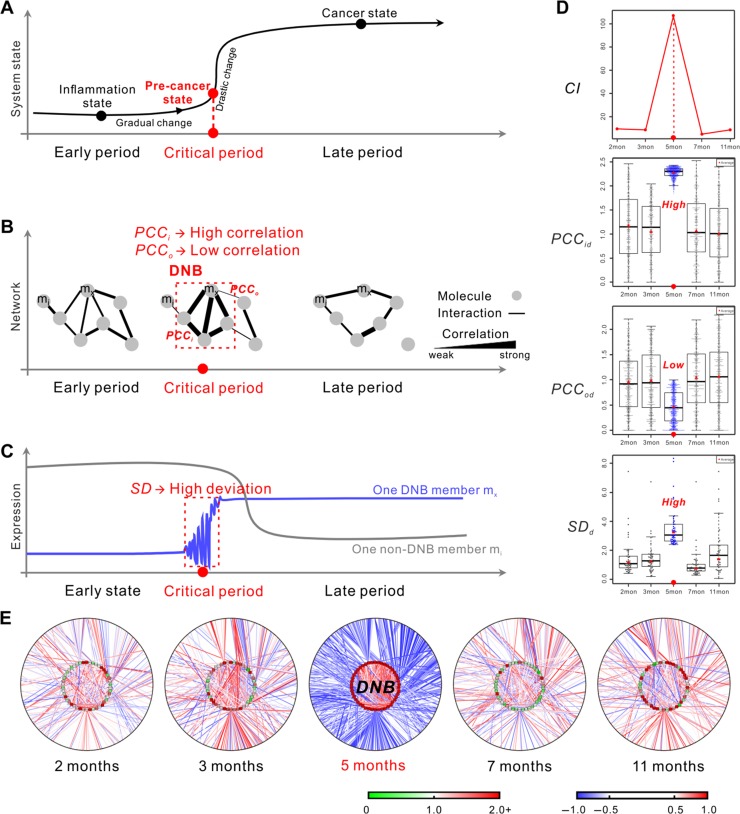

To accurately determine the critical period of cancer initiation, we used our phase transition model with DNB method. Based on the nonlinear dynamic theory, a group of strongly correlated and fluctuated molecules called DNB appear if the state of a system approaches the critical period or tipping point from inflammation to cancer (Chen et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014, 2015). In other words, the appearance of DNB implies the emergence of the critical transition. As shown in Figure 2 (Chen et al., 2012; Sa et al., 2016), when the system gradually approaches the critical state, DNB as a dominant group among all observed molecules can be detected by the following three criteria: (1) Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC) of molecules (expressions) in this dominant group (PCCi) significantly increase (Figure 2B); (2) PCC between molecules in this group and others (PCCo) significantly decrease (Figure 2B); (3) standard deviations (SD) of molecules in this dominant group drastically increase (Figure 2C). An index (CI) considering all three criteria can be used as the numerical signal of DNB method (Li et al., 2014). When CI reaches the peak or increases drastically during the measured periods, we consider that the corresponding period is the critical period of the biological system (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

DNB analysis in the critical transition model identifies the critical period from inflammation to HCC based on proteomic data. (A−C) Schematic illustrations of DNB method. (A) DNB method can identify the pre-cancer state at the critical period, by observing dynamic signals of the corresponding molecules in the dominant group. (B) DNB as a network signals the emergence of the critical transition. When the system approaches the pre-cancer state, PCC of molecule-pairs in DNB or dominant group (PCCi) increase, while PCC between molecules in this group and others (PCCo) decrease. (C) When the system approaches the pre-cancer state, DNB members strongly fluctuate or have high SD near the critical transition, compared with other disease-associated molecules. (D and E) Results of DNB analysis based on label-free proteomic data of 50 samples. (D) This series of diagrams visually show the three key criteria of DNB over five different periods during disease progression. PCCid, PCCod, and SDd are similarly calculated as the definitions of PCCi, PCCo, and SD, after comparing with the corresponding controls. (E) This series of networks graphically demonstrate the dynamic changes in the network structure and concentration variations of the identified DNB and DNB-coexpressed proteins. Clearly, DNB members are strongly correlated and fluctuated at the 5th month, which are recognized as the signals of the critical state. SDd is the differential deviation defined as the ratio of SD between transgenic mice and control mice at the same time point. PCCd is the differential correlation defined as the difference in absolute PCCs between transgenic mice and control mice at the same time point.

Generally, at the critical state, DNB is a group of molecules with strong correlations and fluctuations, which are different from the molecules with differential expressions that are widely used in the traditional methods. As shown in Figure 2A and C, the inflammation and cancer states show significant differences, and thus can be distinguished by traditional (static) biomarkers based on differential expressions. However, there are no significant differences between the inflammation and pre-cancer states in terms of expressions. Thus, it is difficult to identify the pre-cancer state or critical state using traditional biomarkers. By detecting dynamic association (correlation) or fluctuation changes, DNB method can accurately identify the pre-cancer state based on the omics data from both theoretical and computational viewpoints (Chen et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015).

All three main parameters (PCCid, PCCod, and SDd) were calculated by comparing with the age-matched controls, and the algorithm for detecting the critical period and DNB (Supplementary Figure S4) was performed. We identified a strong signal of the critical period shown by CI at the 5th month during chronic inflammation to HCC (Figure 2D), which is consistent with the liver morphological alterations in WHV/c-myc transgenic mouse model and our assumption from Figure 1. The DNB was composed of 48 proteins (Supplementary Table S2), and all indices based on the corresponding DNB were simultaneously satisfied (Figure 2D). We then constructed series of networks with PCC of protein-pairs to illustrate the corresponding dynamics in the network structure and expression variations of the identified DNB and DNB-coexpressed proteins (Figure 2E). Clearly shown in Figure 2E, at the 5th month, the DNB members have strong correlations and fluctuations almost forming a clique in the inner ring, and the links between DNB members in the inner ring and other proteins in the outer ring are significantly increased, which represents drastic changes in coexpression relations or associations within DNB members or between DNB members and other molecules when a biological system approaches the critical state. These data are well in agreement with that presented in Figure 2D.

Validation of critical transition by hematoxylin and eosin-stained histological sections

To validate the above results derived from DNB analysis, we performed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining on liver tissue sections and compared histological images of tissue sections from WHV/c-myc transgenic mice and age-matched control mice at each well-designed time point (Supplementary Figure S5). H&E-stained specimens from WHV/c-myc transgenic mice at 2 months of age were similar to those from wt-C57BL/6 mice. The specimens of normal liver clearly demonstrated the structure of classic lobule. Hepatocytes around a central vein were radially arranged close in single-cell-thick plates separated by vascular sinusoids. The specimens from WHV/c-myc transgenic mice around 3−5 months of age showed disruption of the terminal plate, portal-based inflammation, and local piecemeal necrosis (Ferrell, 2000), which represents that the disease has progressed into hepatitis. Especially, a chaotic microvessel distribution pattern with thin-walled vascular staining could be observed (Cong et al., 2011). Around 7 months of age, hepatocytes were arranged in a thin trabecular pattern and the specimens showed a greater proportion of lesion area with major sinusoidal dilatation (Cong et al., 2011), which represents primary liver tumors. Furthermore, H&E-stained specimens from 11-month-old WHV/c-myc transgenic mice displayed HCC phenotypes (Theise et al., 2002), such as massive and dense arrangement of hepatocytes and increased ratio of nucleus to cytoplasm. Therefore, this histological examination confirmed that 5-month-old transgenic mice stay at the extremely limiting state of inflammation and the 5th month is the critical point of cancer initiation.

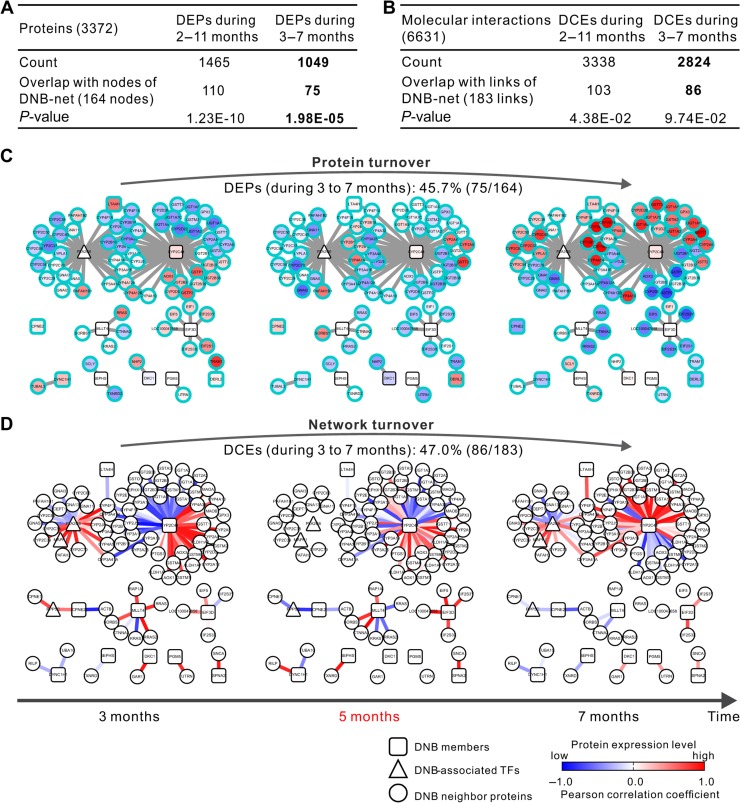

The DNB-associated network is rewired before and after the critical transition

Complex diseases generally result from abnormalities in the systematic interplay of multiple molecules and even biological processes (Chuang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011; Rolland et al., 2014). Thus, it is necessary to integrate relatively complete interactome of the corresponding organism for a comprehensive understanding of HCC pathological mechanisms at a molecular level. DNB is a group of proteins with strong correlations and fluctuations at the pre-cancer state (or critical state), which are different from DEPs (or DCEs) between the inflammation and cancer states. DNB members are considered to induce the critical transition from the inflammation to cancer states, while DEPs (or DCEs) may actually facilitate biological functions in the cancer state. To study the coordination between DNB members and DEPs (or DCEs), we constructed the DNB-associated network (164 proteins with 183 links) by integrating DNB members and their first-order neighbors (Supplementary Figure S6A) according to whole molecular network of mouse. Then, we counted nodes (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S6B) or links (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S6C) that belong to DEPs or DCEs, respectively, and measured their overlapping significance with the DNB-associated network by the hypergeometric test, which implied the coordination between DNB and DEPs or DCEs. Furthermore, the dynamic changes of the DNB-associated network in expressions (Figure 3C) and coregulations (or coexpressions) (Figure 3D) for transgenic mice and control mice (Supplementary Figure S7) were graphically illustrated. In total, 75 (out of 164) DNB-associated DEPs showed inversed expression levels (Figure 3C and Supplementary Table S2) and 86 (out of 183) DNB-associated DECs showed inversed coregulation links (Figure 3D and Supplementary Table S3) before and after the critical period in transgenic mice. These results suggest that DNB members, especially PLA2G6 and CYP2C44 as hubs of the largest inversing sub-network, coordinate with DEPs and DCEs to induce the critical transition from inflammation to HCC. It should be noted that the correlation-based network with both direct and indirect associations was used in this study, and analyses based on the network with only direct associations can further improve the accuracy (Zhang et al., 2013, 2015b; Zhao et al., 2016).

Figure 3.

Rewiring of the DNB-associated network with dynamic changes of DEPs or DCEs before and after the critical period. (A and B) Significant overlapping between nodes in the DNB-associated network and DEPs (A) or between links of the DNB-associated network and DCEs (B) during the whole period (2−11 months) and during 3−7 months (including 3 vs. 5, 5 vs. 7, and 3 vs. 7 months) implies functional relations between DNB members and DEPs or DCEs, especially during the critical period. (C and D) Dynamic changes of the DNB-associated network in expressions (C) and coregulations (D) before and after the critical period. The expressions of 75 DNB-associated DEPs (Supplementary Table S2) and correlations or regulations of 86 DNB-associated DCEs (Supplementary Table S3) significantly changed (or inversed) before and after the critical period in transgenic mice, implying key roles of DNB members in coordinating the critical transition from inflammation to HCC across the 5th month.

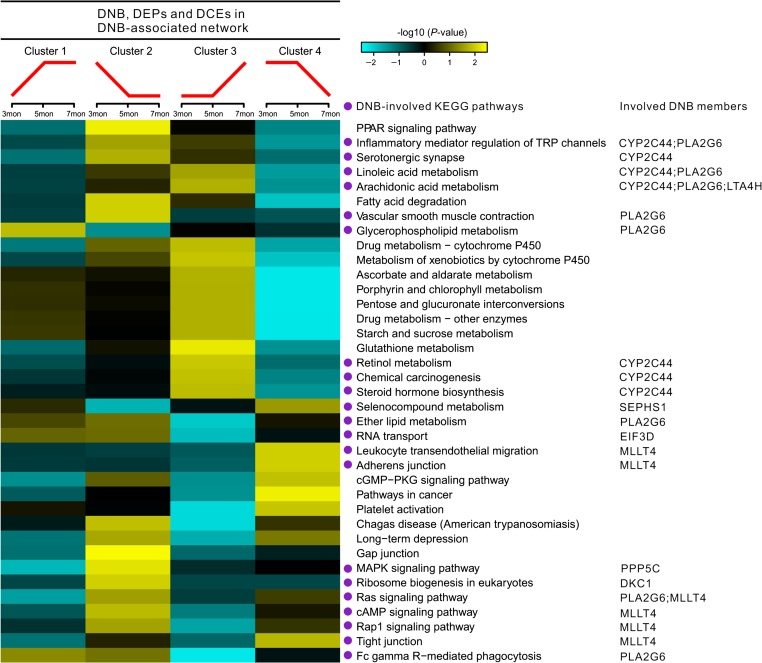

Dynamics of functional phenotypes influenced by the DNB-associated network before and after the critical transition

To understand DNB-involved dysfunctions in inflammation-induced carcinogenesis, functional analyses on dynamic patterns of DNB-associated DEPs and DCEs before and after the critical transition were performed. First, DNB-associated DEPs (75 proteins) and DCEs (86 links) were classified by Mfuzz (Futschik, 2015) into four clusters (Supplementary Figure S8), according to their expression or coexpression profiles during two consecutive periods (e.g. 3−5 months and 5−7 months). Members of Clusters 1 and 2 were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, before the critical point (5 months after birth), while members of Clusters 3 and 4 were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, after the critical point. Thus, DEPs or DCEs within Clusters 1 and 2 may be influenced by their associated DNB members earlier than those within Clusters 3 and 4.

Next, functional analyses were performed with members of each cluster. A total of 97 KEGG pathways (Supplementary Table S4, adjusted P < 0.05) were clustered according to the z-transformed P-values by measuring their enrichments in the 4 clusters (Pan et al., 2009), among which 37 pathways were chosen and listed in Figure 4. Unexpectedly, 8 DNB members (e.g. PLA2G6, CYP2C44, LTA4H) were directly involved in 22 out of these 37 pathways. Meanwhile, in these 22 pathways, lipid metabolism (n = 5) was most enriched with nodes in the rewired DNB-associated network (Supplementary Table S4), indicating that lipid metabolism may play a key role during the critical period. Moreover, PLA2G6 and CYP2C44 were the only two DNB members that participate in these lipid metabolic pathways.

Figure 4.

Functional phenotyping of DNB, DEPs, and DCEs in the DNB-associated network. Four clusters were classified by Mfuzz clustering in R to represent the dynamic expression or coregulation patterns. The heatmap shows related KEGG pathways, which were clustered according to the enrichments of corresponding proteins in different dynamic patterns.

Before the critical period, glycerophospholipid metabolism (one of lipid metabolic pathways) is mainly affected by the members of Cluster 1. Fifteen pathways involving metabolism, signal transduction, and inflammatory are mainly affected by the members of Cluster 2, including fatty acid degradation (lipid metabolic pathway), Ras, Rap1, cAMP, and MAPK signaling pathways (signal transduction), and inflammatory mediator regulation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (sensory system). Ether lipid metabolism (another lipid metabolic pathway), RNA transport (translation pathway), and Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis (immune pathway) are affected by the members of both Clusters 1 and 2, suggesting more complicated regulations in these processes.

After the critical period, dysfunctions of carbohydrate, lipid, and xenobiotics metabolisms are significantly affected by the members of Cluster 3, while dysfunctions of cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (e.g. tight junction and adherens junction) and immune surveillance and inflammation (e.g. leukocyte transendothelial migration and platelet activation) are significantly affected by the members of Cluster 4.

These results agree with previous reports that, in addition to signal transduction and cell communication, Warburg effect (both carbohydrate and lipid metabolisms), inflammation, and immunity-involved pathways also play key roles in the transition from inflammation to cancer initiation (Vander Heiden et al., 2009; Vander Heiden, 2011; Flaveny et al., 2015). Similar results were obtained by conducting functional analyses separately with DNB-associated DEPs or DCEs (Supplementary Figure S9), which showed that DEPs and DCEs played different roles during the disease progression. Moreover, we hypothesize that the sub-network involving PLA2G6 and CYP2C44 as two hubs plays a key role during the critical period to drive the disease progression from inflammation to cancer, i.e. strongly collective fluctuations of PLA2G6 and CYP2C44 affect their associated DEPs or DCEs and sequentially destabilize their involved lipid metabolic pathways at the inflammation state, which eventually makes the system transit to the cancer state.

Validation of label-free profiles for the dynamics of the DNB-associated network by tandem mass tag labeling

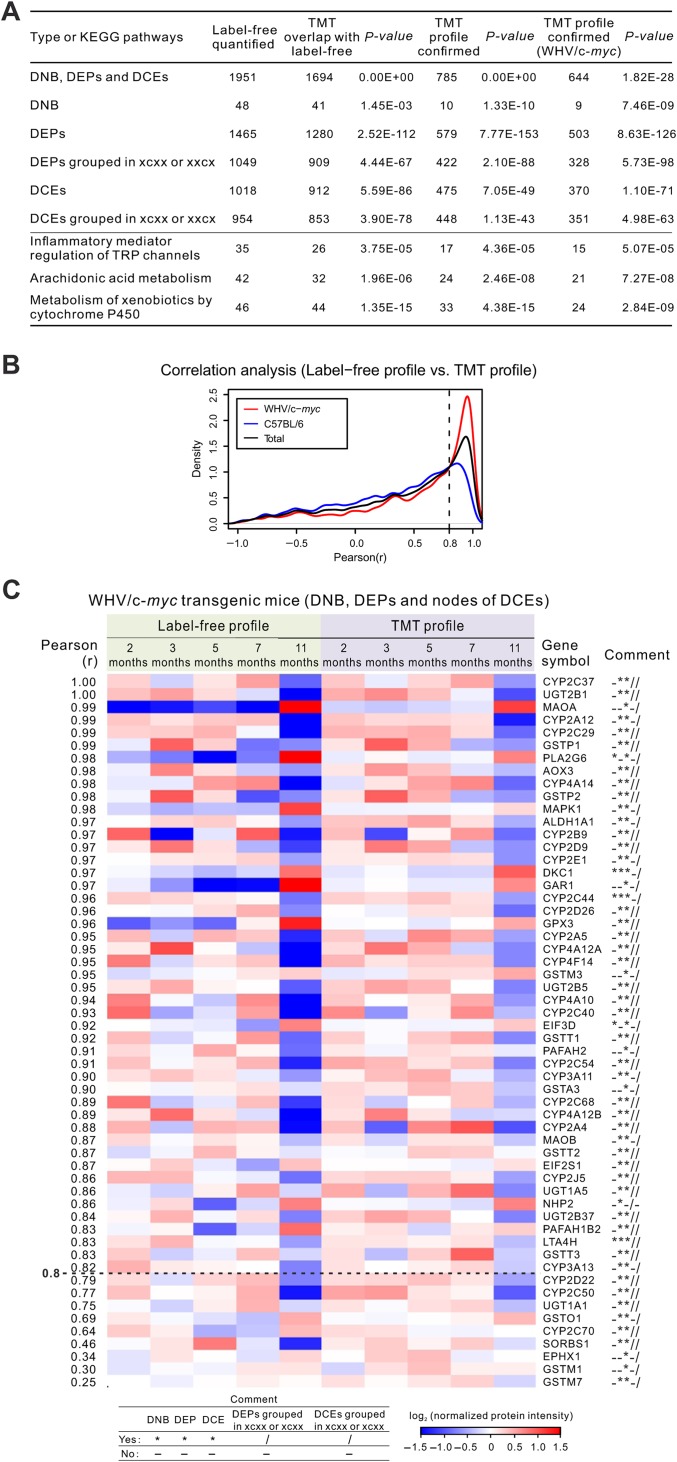

To validate previous results derived from label-free quantified data, we re-quantified the proteomic data using an in vitro chemically stable isotope labeling technique, tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling (the overlapping part with label-free data is shown in Supplementary Table S2). On one hand, dynamic protein profiles could be monitored on a large scale by TMT reporter ion intensities. On the other hand, relative protein quantification in multiple samples can be determined in a single experiment through tagging peptides with TMT isobaric tags (Thompson et al., 2003). To minimize the individual variation and to achieve more stable protein profiles in TMT proteomic tests, liver lysates were pooled for transgenic or control mice of each time point during the progression from inflammation to cancer. Then, we separated each mixture sample into fractions using a widely applied fractionation strategy, which resulted in 4188 TMT-quantified proteome with a protein FDR 0.01. Each TMT experiment has three technical repeats. As a result, the average relative standard deviation (RSD) was 10.4% (WHV/c-myc transgenic mice) or 9.4% (wt-C57BL/6 mice), reflecting good reproducibility of the TMT experiments.

As shown in Figure 5A, most DNB, DEPs, and DCEs previously found in label-free tests were confirmed by TMT tests, which means that TMT proteomic dataset can be used to validate label-free proteomic dataset as a whole. Correlation analysis revealed that the density curve of PCC between label-free profile and TMT profile in transgenic mice was much closer to 1.0 (Figure 5B). Nevertheless, the label-free profile was considered being confirmed by TMT experiments when PCC between label-free profile and TMT profile is >0.8, fold change between two optional time points is >1.5, and P-value by Student’s t-test is <0.05. The DNB-associated DCE links were considered being confirmed only if PCC between label-free profile and TMT profile is >0.8 for both DNB nodes and its neighbor nodes. According to these criteria, we were able to reproduce the dynamic profiles of considerable DNB-associated DEPs (Figure 5C) and DCE links (Supplementary Figure S10) mentioned in Figure 3 and validate the involved biological pathways (Figure 5A), indicating a good reliability of the DNB-associated network. The PCC between label-free profile and TMT profile was equal to 0.98 and 0.96 for PLA2G6 and CYP2C44, respectively (Figure 5C and Supplementary Table S5A). Moreover, 20 CYP2C44-involved, 2 PLA2G6-involved, and 1 DKC1-involved DCE links (Supplementary Figure S10 and Table S5B) had high PCC (>0.8) between label-free and TMT quantification strategies.

Figure 5.

Validation of DNB, DEPs, and DCEs by TMT proteomic data. (A) Comparison between label-free and TMT profiles. For xcxx and xxcx, c means ‘must be changed’ during 3−5 months or 5−7 months, and x means ‘not required to be changed’. (B) Density curves of PCC between label-free profile and TMT profile in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice (red), C57BL/6 control mice (blue), and both mice (black). (C) A heatmap shows the reproduced dynamic profiles with validated DNB, DEPs, and linked (second) nodes of DCE links (PCC > 0.8) in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice. More information of 136 nodes is listed in Supplementary Table S5, and second nodes of the DCEs in Supplementary Figure S10.

Downregulation of PLA2G6 in clinical high-grade dysplastic nodules as an early-warning biomarker for liver cancer initiation

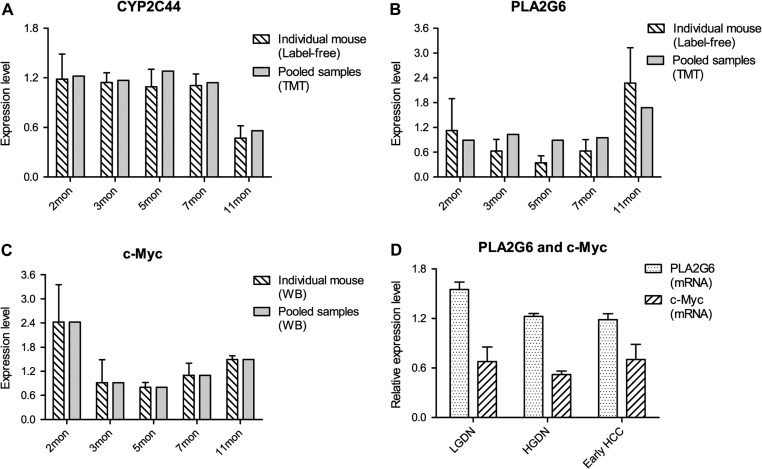

DNB is expected to be used for early diagnosis of imminent cancer initiation. We focused on the two hubs inversing the DNB-associated network, PLA2G6 and CYP2C44, to exploit their potential in clinical application. To investigate the roles of these two hubs in liver cancer initiation of WHV/c-myc transgenic mice, we traced dynamic expression levels of CYP2C44 (Figure 6A) and PLA2G6 (Figure 6B) in both individual mouse (label-free profile) and pooled samples (TMT profile). Interestingly, CYP2C44 and PLA2G6 expression changes were not detected during 3−7 months including the critical transition of carcinogenesis but only observed after the critical transition (11 months). Since PLA2G6 is directly bound to and regulated by the oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc (Zeller et al., 2003), one of the driving factors to induce hepatocellular carcinogenesis in the WHV/c-myc transgenic mouse model, we then examined dynamic protein expression level of c-Myc by western blot analysis. The results demonstrated that the expression levels of PLA2G6 and its driver c-Myc showed a positive correlation in the trend from decreasing to increasing during carcinogenesis, with the minimal point at the critical period (5 months) before the disease state (Figure 6B and C). This implies that PLA2G6 may function as an oncogene like c-Myc in hepatocarcinogenesis.

Figure 6.

PLA2G6 downregulation at the tipping point or during the critical period of liver cancer initiation. Relative protein expression levels of CYP2C44 (A), PLA2G6 (B), and c-Myc (C) in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice. Similar profiles were obtained from individual mouse (shadow-bar) and pooled samples (gray-bar). (D) Relative gene expression levels of PLA2G6 and c-Myc of patients with LGDN, HGDN, or early HCC.

Furthermore, by using mouse PLA2G6 and CYP2C44 protein sequences as the query sequences in the homologous sequence analysis, we found the homologous PLA2G6 in humans. Then, we checked the mRNA expression levels of PLA2G6 and c-Myc in the gene expression profile from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, GSE12443) on patients with low-grade dysplastic nodules (LGDN), high-grade dysplastic nodules (HGDN), or early HCC (Kaposi-Novak et al., 2009). We found similar changing trends in expression levels of homologous PLA2G6 and c-Myc in humans as observed in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice, with the minimal point at HGDN, a critical inflammation stage just before the cancer initiation (Figure 6D). Because HGDN is considered as the critical period of hepatocellular carcinogenesis due to its high risk of tumorigenesis within 5 years (Borzio et al., 2003; Kobayashi et al., 2006), downregulation of PLA2G6 and c-Myc can be considered as an early-warning signal for liver cancer initiation from chronic inflammation.

Discussion

In this study, by analyzing time-series proteomic data based on DNB method, we identified that the critical period from inflammation to cancer is the 5th month after birth of WHV/c-myc transgenic mice, which was consistent with the disease progression shown in Figure 1A and histological grade of H&E-stained liver specimens. By integrating DNB members and their first-order DEPs and DCEs into the DNB-associated network based on whole molecular network of mouse, we found that many DEPs and DCEs showed inversed expressions from high (low) to low (high) or regulations from positive (negative) to negative (positive) in transgenic mice before and after the critical period, especially in the sub-network made of two DNB members PLA2G6 and CYP2C44. Functional analysis for the DNB-associated network implied that dysfunction of PLA2G6 and CYP2C44-associated arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism disturbs inflammatory responses through inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels and xenobiotics metabolism involving typical CYP family, leading to impairments of liver detoxification and malignant transition to cancer. Furthermore, PLA2G6 was found to be a direct target of c-Myc and may function as an oncogene like c-Myc during hepatocarcinogenesis. The expression levels of PLA2G6 and c-Myc showed a trend from decreasing to increasing during carcinogenesis, with the minimal point at the critical transition period or tipping point in the mouse model or at HGDN (a critical inflammation stage just before the cancer initiation) in humans. These results suggest that downregulation of PLA2G6 and c-Myc can be considered as an early-warning signal for liver cancer initiation from chronic inflammation.

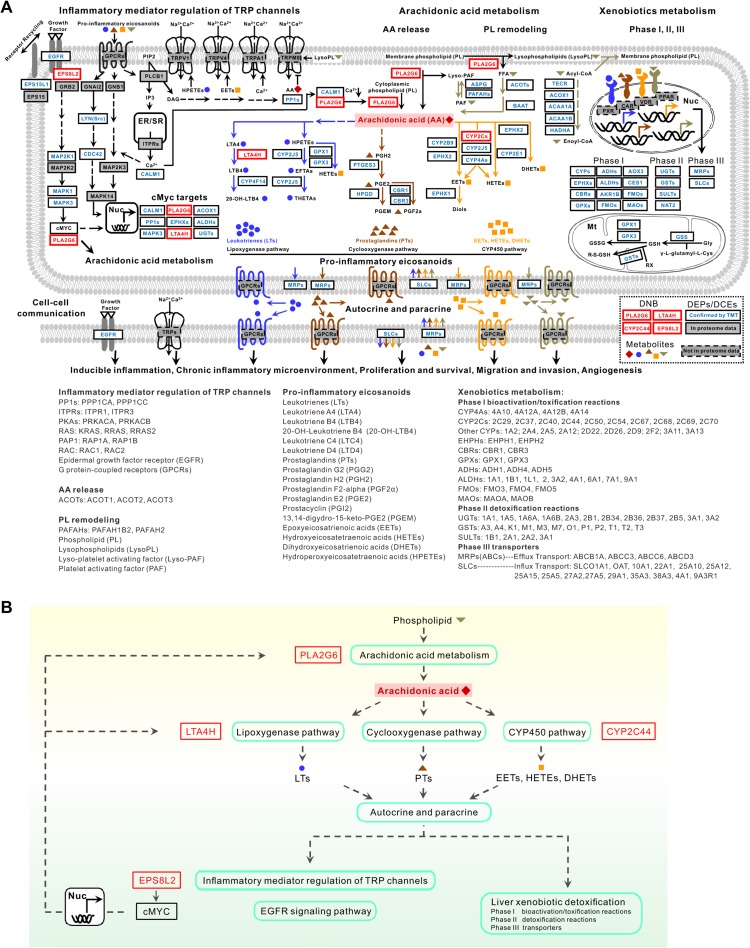

A schematic diagram in Figure 7 demonstrates potential molecular mechanisms underlying the sequential dysfunctions of AA metabolism, inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels, and xenobiotics metabolism, which are mainly mediated by PLA2G6 and CYP2C44, with two other DNB members, LTA4H and EPS8L2, and some key proteins belonging to DEPs or DCEs. All proteins of the involved signaling cascades were specifically colored based on the results from our real label-free and TMT datasets. The DNB-associated DEPs or DCEs in Figure 7A mainly take part in typical cancer-associated functions or pathways, such as production and transportation of active metabolites (e.g. pro-inflammatory eicosanoids) (Woutersen et al., 1999; Panigrahy et al., 2010; Wang and Dubois, 2010; Park et al., 2012), autocrine and paracrine manners of the transformed cells (Wang and Dubois, 2010), precise controls of TRP channels (Chen et al., 2014), phospholipid (PL) remodeling (Park et al., 2012), liver xenobiotics (Nie et al., 2012; Osterreicher and Trauner, 2012), and c-Myc-driven gene expressions (Lin et al., 2012; Nie et al., 2012). Thus, we suppose a circulation between AA metabolism and inflammation, which worsens liver impairments and triggers carcinogenesis.

Figure 7.

DNB-associated aberrant AA and xenobiotics metabolisms and abnormal inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels. (A) A schematic diagram shows that dysfunction of PLA2G6 and CYP2C44-associated AA metabolism activates inflammatory responses through inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels, which can lead to impairments of liver detoxification and further malignant transition to cancer. The dynamic expression profile of 136 proteins in this diagram derived from the comparison between label-free and TMT profiles was summarized in Supplementary Table S5. (B) A simplified diagram for A.

As shown in Figure 7B, AA that may have opposing functions in different tumor microenvironments (Panigrahy et al., 2010) occupies a central position in this schematic diagram. AA is a bioactive lipid mediator and comes from PL remodeling mainly mediated by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Park et al., 2012). PLA2 was reported to have both growth-inhibiting and growth-promoting effects. The 85 kDa calcium-independent PLA2, i.e. PLA2G6 (Group VIA PLA2, iPLA2ß), is one of the key DNB members identified in our study, which is an enzyme encoded by the Pla2g6 gene in humans. PLA2G6 belongs to a subclass of enzyme that catalyzes the release of fatty acids from phospholipids and is involved in stimulus-induced AA release (Akiba and Sato, 2004). It has been reported that PLA2G6 may play important roles in PL remodeling, AA release, leukotriene (LT) and prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis, and transmembrane ion flux in glucose-stimulated B-cells (Kienesberger et al., 2009). PLA2G6, as one of c-Myc targets, is significantly upregulated at 11 months after birth of transgenic mice in both label-free and TMT datasets, while PLA2G6-associated downstream pathways distinctly change during 3−7 months including the critical period (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S5B). For instance, PLA2G6-associated DEPs are scattered in both Clusters 1 and 2 (up- or downregulated before the critical period) and Cluster 3 (upregulated after the critical period) (Supplementary Table S5A), while PLA2G6-involved DCEs are scattered in all four types of clusters or patterns (Supplementary Table S5B and Figures S9, S10). Specifically, PLA2G6-associated DEPs mainly take part in four lipid metabolic pathways (AA, linoleic acid, glycerophospholipid, and ether lipid metabolism) and three organismal systems pathways (Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, and vascular smooth muscle contraction) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S9). PLA2G6 also mediates the generation of lyso-platelet activating factor (Lyso-PAF), lysophospholipids (LysoPL), and free fatty acid (FFA) and the re-utilization of acyl-CoA for PL remodeling (Akiba and Sato, 2004). Interestingly, FFA in PL remodeling can be metabolized to other active lipids, including AA mediated by ACOTs and BAAT (Supplementary Table S5A).

Bioactive eicosanoids can act as small molecule mediators to impact on inflammation and cancer (Woutersen et al., 1999; Panigrahy et al., 2010; Wang and Dubois, 2010). For instance, the pro-inflammatory PGs and LTs can directly induce epithelial tumor cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion in autocrine and paracrine manners (Wang and Dubois, 2010); hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) play pro-inflammatory roles in cancer biology (Moreno, 2009); and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) demonstrate anti-inflammatory activity (Zeldin, 2001). These eicosanoids can be produced downstream of AA release via cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX), and cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathways (Figure 7B; Wang and Dubois, 2010).

Cytochrome P450-derived AA metabolism has recently come into sight, notably involving syntheses of 20-HETE and EETs (Panigrahy et al., 2010). It has been subdivided into two distinctive pathways, i.e. epoxygenases mainly for EETs, dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs), and dihydrodiols (Diols) and ω-hydroxylases for HETEs (Greene et al., 2011). Another key DNB member identified in our work, CYP2C44, is placed upstream to regulate this pathway. Unexpectedly, many proteins involved, especially those downstream of CYP2C44, belong to the identified DEPs or DCEs, suggesting that the homeostasis of EETs is damaged, which may affect inflammation and lead to cancer initiation. Meanwhile, CYP2C44 has been identified as one of endothelial epoxygenases that also take part in angiogenesis (Pozzi et al., 2007) Its coding gene is considered a host pro-angiogenic and pro-tumorigenic epoxygenase gene regulated by anti-angiogenic and anti-tumorigenic effects of PPARα ligand activation (Pozzi et al., 2010). These phenomena suggest that keeping homeostasis of bioactive eicosanoids may be a potential and effective anti-inflammatory strategy.

Another DNB member, LTA4H, participates in LOX pathway-mediated AA metabolism to synthesize LTs. LTA4H is a pro-inflammatory enzyme to generate LTB4 (Snelgrove et al., 2010), one of important inflammatory mediators that can stimulate growth of human pancreatic cancer cells via MAPK and PI-3 kinase pathways (Tong et al., 2005). Interestingly, LTA4H shows significantly inversed patterns of both expression and regulation during 3−7 months in transgenic mice (Figure 3C, D and Supplementary Table S4). However, LTA4H is downregulated at 11 months in transgenic mice, which makes the role of LTA4H puzzled. Recent studies elucidated the bifunctional roles of LTA4H, i.e. proinflammatory via LTB4 generation and anti-inflammation via Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP) degradation (Snelgrove et al., 2010). Our results gave a clue to the anti-inflammatory role of LTA4H, because prolyl endopeptidase (PREP), which specifically cleaves collagen within the lung to generate the neutrophil chemoattractant peptide PGP (Snelgrove et al., 2010), is significantly upregulated in 11-month-old transgenic mice (Figure 7A and Supplementary Table S5). Thus, uncovering the bifunctions of LTA4H could contribute to novel strategies for preventing the inflammation-to-cancer transition and cancer therapy.

The xenobiotic detoxification system is critical to deal with unexpected exogenous and endogenous metabolites in three phases (Nie et al., 2012). In Phase I, CYPs can convert target compounds into more soluble derivatives that are suitable for excreting from the body by hydroxylation or oxidation reactions (Guengerich, 2001; Nie et al., 2012). Phase II conjugation reactions are catalyzed by a large group of transferases, which conjugate polar functional groups onto xenobiotics and endobiotics to produce water-soluble, inactive metabolites suitable for biliary and urinary excretion (Ayrton and Morgan, 2008). In Phase III, hepatic transporter proteins play a crucial role in both influx and efflux of xenobiotics and endogenous compounds into and out of the cell (Corsini and Bortolini, 2013). Many proteins participating in a certain phase of liver detoxification (Figure 7A) were identified to have significantly differential changes in either expression or regulation (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S3), indicating that dysfunction of liver detoxification may impact on hepatic impairments to worsen the microenvironment and promote carcinogenesis.

Recent studies have indicated that TRP channels are associated with tumors and might represent potential targets for cancer treatment (Chen et al., 2014). Mammalian TRP channels show low sequence homology and a wide variety of modes of activation, regulation, ion selectivity, broad tissue distribution, and physiological functions (Levine and Alessandri-Haber, 2007). There are many kinds of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) upstream of this pathway, responding specifically to the corresponding small metabolites (e.g. LTs, PTs, EETs, HETEs, and DHETs). Therefore, we hypothesize that this pathway may be downstream of the bioactive eicosanoids and trigger inflammation-induced carcinogenesis.

Interestingly, another DNB, EPS8L2, takes part in regulating the transcription factor effects of both c-Myc and PLA2G6 on growth factor-stimulated EGFR signaling pathway, which plays an important role in membrane ruffling and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Some c-Myc targets, like DKC1 and MAPK3, are also involved (Figure 4). Activated PLA2 can induce the release of AA metabolites and pro-inflammatory eicosanoids (Figure 7), such as AA itself, HPETE, or 5,6-EET that, in turn, act as agonists of certain TRP channels (Levine and Alessandri-Haber, 2007). We notice that the catalytic activity of PLA2G6 is regulated by protein kinase C, calmodulin, and others such as reactive oxygen species (Akiba and Sato, 2004). Although the activity of iPLA2 does not require Ca2+, it is reported to be regulated by the amount of Ca2+ in intracellular Ca2+ stores or by the calcium-dependent protein calmodulin, which was also observed in our data. The CALM1-PYGB link was found to be regulated from negative correlation to positive correlation during the critical process in transgenic mice, and the positive correlation lasted until 11 months.

Here, we showed that PLA2G6 and CYP2C44-associated DNB network plays crucial roles in mediating the critical transition from inflammation to HCC, signaling the imminent cancer initiation as an early-warning biomarker during the chronic disease progression. This work not only opens a new way to identify the critical transition for HCC from dynamic and network perspectives, but also helps us to understand the pathogeneses of c-myc-induced hepatocarcinogenesis or human-suffered hepatitis virus-associated HCC, which may provide new insights into intervention strategies to prevent from malignancy of chronic hepatitis.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments and liver tissue sample preparation

Twenty-five male WHV/c-myc transgenic mice from C.A. Renard (Institute Pasteur, France) and 25 male wt-C57BL/6 mice from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center were housed in a satellite vivarium at constant temperature and humidity with standard 12-h light/dark cycles and allowed ad libitum water and food under the specific pathogen-free condition. All animal experiments were performed under strict governmental and international guidelines. At each well-designed time point (2, 3, 5, 7, or 11 months after birth), 5 transgenic mice and 5 age-matched controls were sacrificed (Supplementary Figure S1).The liver tissue samples were collected for proteome analysis. Details of sample preparation for proteome analysis are described in the legend of Supplementary Figure S1.

Proteomic data by label-free LC–MS/MS

We applied the pCOG method with strong cation exchanger and reversed phase separation to perform proteome analysis on a LTQ MS (Thermo Finnigan), as described in Zhou et al. (2007).The LC system was interfaced to a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan) with electrospray ionization operated in positive mode. Precursors (m/z: 400–2000) were subjected to data-dependent and collision-induced dissociation with 35.0% normalized collision energy. We set the mass spectrometer as that one survey scan was followed by 10 MS/MS on the top 10 most intense precursors from the MS spectrum, with the following dynamic exclusion: repeat count 2, repeat duration 30 sec, exclusion duration 90 sec.

Using SEQUEST (University of Washington, licensed to Thermo Finnigan), all MS/MS spectra from each raw file obtained from previous steps were searched against a concatenated target-decoy database derived from the Mouse International Protein Index protein sequence database (IPI mouse database, version 3.82) (Kersey et al., 2004). Searching parameters included the precursor mass tolerance that was set to 3 Da, fully trypsin digestion, 1 maximum mis-cleavage site, and a static modification of cysteine (Carbamidomethylation, +57 Da). We used Buildsummary (Tang et al., 2007), a home-made software, to integrate the previously searched results. All peptides were assigned corresponding ΔCn scores > 0.1 (regardless of charge state), with peptide length >6 amino acids, filtered by peptide FDR according to hits coming from reverse database (Elias and Gygi, 2007).

Proteomic data by TMT quantification

In order to confirm the dynamic profiles of the DNB-associated network from label-free quantified proteomic data, liver lysates from three WHV/c-myc transgenic mice and three C57BL/6 mice, respectively, at each time point were pooled and re-measured by TMT proteomic experiments. Both forward labeling and reversed labeling were adopted to eliminate errors among different channels. In other words, each mixture sample was labeled by two different stable isotope tags in two TMT tests, which showed good correlation. The peptides were labeled by TMT kits following the standard protocol.

Then OFFGEL fractionation was performed on the Angilent 3100 OFFGEL fractionator along 3–10 NL pH range. Each TMT-labeled mixture was fractionated into 6 fractions, and then each fraction was desalted and analyzed for 3 times on nanoHPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap-Velos (Thermo Electron Finnigan). TMT-labeled mixtures were separated through a nano-emitter column (15-cm length, 75-μM inner diameter) packed in-house with 3-μM C18 ReproSil particles (Dr. Maisch GmbH) and introduced into MS via a nanoelectrospray ion source (source voltage, 2 kV). A linear gradient from 4% to 30% buffer B (buffer A, 0.1% formic acid in ddH2O; buffer B, 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) over 150 min was used for peptide separation at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. Higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) was performed, with a resolution of 30000 at m/z 400 for full scan and 7500 for MS/MS scans. Top 10 ions were selected at an isolation window of 2.0 m/z units and accumulated to an AGC target value of 3e4 for MS/MS sequencing. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 90 sec to avoid choosing former target ions, and lock-mass was enabled using 445.120025.

Raw MS data were processed using the MaxQuant software (Cox and Mann, 2008) version 1.3.0.5 using the default settings with minor changes: oxidation (Methionine) and acetylation (Protein N-term) were selected as variable modifications and carbamidomethyl (C) as fixed modification. TMT-labeled amino acid filtering was selected. Database searching was performed using the Andromeda search engine (Cox et al., 2011) against UniProt mouse sequence database (released June 2012, 59375 protein entries), concatenated with known contaminants and reversed sequences of all entries. A FDR < 0.01 for proteins and peptides and a minimum peptide length of 6 amino acids were required.

DNB analysis

Based on the nonlinear dynamical theory, a system is near the critical state if there is a dominant group of molecules, i.e. DNB, among all observed molecules satisfying three criteria (Chen et al., 2012). The following quantification index (CI) considering all three criteria can be used as the numerical signal of DNB method:

where size is the number of molecules in the dominant group among all observed molecules, PCCi is the average PCC of the dominant group in absolute value, PCCo is the average PCC between the dominant group and others in absolute value, and SDi is the average standard deviation of the dominant group.

When CI reaches the peak or increases drastically during the measured periods, we consider this period as the critical period of the biological system. The DNB does not distinguish disease samples but pre-disease samples from normal samples by using molecular fluctuation information (i.e. dynamical information) and also network information (i.e. correlation information among molecules). The detailed algorithm is shown in Supplementary Figure S4. After obtaining the dominant group of molecules, we added the transcription factors with direct interactions or regulations together as DNB members.

Functional analysis

To uncover potential HCC-associated biological functions affected by the identified proteins, we mapped these proteins into known molecular sets with functional annotations. KEGG (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) was used for canonical pathway detection. Enrichment significance of specific proteins in each biological process or pathway was estimated by the hypergeometric test. Significantly enriched functions were chosen by the corresponding P-value < 0.05 after FDR correction.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed to confirm the change of c-Myc expression. Briefly, ~20 μg proteins from individual or pooled samples were loaded. Antibody for c-Myc (Sigma) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Background was subtracted from all signals determined with the Science Lab software (Fuji). Relative protein expression levels were determined by the mean optical density minus background per area units (Q–B/pixel2). The protein expression profile accorded well with the gene expression profile as previously described (Etiemble et al., 1994; Farazi and DePinho, 2006), which clearly demonstrated an overall upregulation of c-Myc in WHV/c-myc transgenic mice.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Journal of Molecular Cell Biology online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0505500), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (XDB13040700 and XDA12010000), the National Program on Key Basic Research Project (2014CB910504, 2011CB910601, and 2014CBA02000), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (91439103, 91529303, 30700397, 81471047, 61134013, and 81471047). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of SA-SIBS Scholarship Program.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to members of Chen lab and Zeng lab for kind discussions. We appreciate Drs P. Tiollais and C.A. Renard (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France) for their generous gifts of WHV/c-myc mice and comments on feeding or crossing the mice.

References

- Akiba S., and Sato T. (2004). Cellular function of calcium-independent phospholipase A2. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 27, 1174–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayrton A., and Morgan P. (2008). Role of transport proteins in drug discovery and development: a pharmaceutical perspective. Xenobiotica 38, 676–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer S., Zetterberg A., Ihrie R.A., et al. (2004). Developmental context determines latency of MYC-induced tumorigenesis. PLoS Biol. 2, e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrello M.G., Degl’Innocenti D., and Pierotti M.A. (2008). Inflammation and cancer: the oncogene-driven connection. Cancer Lett. 267, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borzio M., Fargion S., Borzio F., et al. (2003). Impact of large regenerative, low grade and high grade dysplastic nodules in hepatocellular carcinoma development. J. Hepatol. 39, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Luan Y., Yu R., et al. (2014). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, promising potential diagnostic and therapeutic tools for cancer. Biosci. Trends 8, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Liu R., Liu Z.P., et al. (2012). Detecting early-warning signals for sudden deterioration of complex diseases by dynamical network biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2, 342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H.Y., Lee E., Liu Y.T., et al. (2007). Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W.M., Dong H., Tan L., et al. (2011). Surgicopathological classification of hepatic space-occupying lesions: asingle-center experience with literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 2372–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini A., and Bortolini M. (2013). Drug-induced liver injury: the role of drug metabolism and transport. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53, 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., and Mann M. (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Neuhauser N., Michalski A., et al. (2011). Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1794–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diakos C.I., Charles K.A., McMillan D.C., et al. (2014). Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 15, e493–e503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias J.E., and Gygi S.P. (2007). Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etiemble J., Degott C., Renard C.A., et al. (1994). Liver-specific expression and high oncogenic efficiency of a c-myc transgene activated by woodchuck hepatitis virus insertion. Oncogene 9, 727–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi P.A., and DePinho R.A. (2006). Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 674–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell L. (2000). Liver pathology: cirrhosis, hepatitis, and primary liver tumors. update and diagnostic problems. Mod. Pathol. 13, 679–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaveny C.A., Griffett K., El-Gendy Bel D., et al. (2015). Broad anti-tumor activity of a small molecule that selectively targets the Warburg effect and lipogenesis. Cancer Cell 28, 42–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futschik M. (2015). Mfuzz: Soft clustering of time series gene expression data. R package version 2.30.30, http://www.sysbiolab.eu/software/R/Mfuzz/index.html.

- Greene E.R., Huang S., Serhan C.N., et al. (2011). Regulation of inflammation in cancer by eicosanoids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 96, 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich F.P. (2001). Common and uncommon cytochrome P450 reactions related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 611–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D., Liu Z.P., Honda M., et al. (2012). Coexpression network analysis in chronic hepatitis B and C hepatic lesions reveals distinct patterns of disease progression to hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 140–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Liu S., et al. (2013). Quantitative proteomic analysis identified paraoxonase 1 as a novel serum biomarker for microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 12, 1838–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S.P., and Harris C.C. (2007). Inflammation and cancer: an ancient link with novel potentials. Int. J. Cancer 121, 2373–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.H., Atluri G., Kuang R., et al. (2013). Large-scale integrative network-based analysis identifies common pathways disrupted by copy number alterations across cancers. BMC Genomics 14, 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhunjhunwala S., Jiang Z., Stawiski E.W., et al. (2014). Diverse modes of genomic alteration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genome Biol. 15, 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Jhunjhunwala S., Liu J., et al. (2012). The effects of hepatitis B virus integration into the genomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Genome Res. 22, 593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., and Goto S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi-Novak P., Libbrecht L., Woo H.G., et al. (2009). Central role of c-Myc during malignant conversion in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 69, 2775–2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P.J., Duarte J., Williams A., et al. (2004). The International Protein Index: an integrated database for proteomics experiments. Proteomics 4, 1985–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienesberger P.C., Oberer M., Lass A., et al. (2009). Mammalian patatin domain containing proteins: a family with diverse lipolytic activities involved in multiple biological functions. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl), S63–S68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M., Ikeda K., Hosaka T., et al. (2006). Dysplastic nodules frequently develop into hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic viral hepatitis and cirrhosis. Cancer 106, 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J.D., and Alessandri-Haber N. (2007). TRP channels: targets for the relief of pain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 989–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zeng T., Liu R., et al. (2014). Detecting tissue-specific early-warning signals for complex diseases based on dynamical network biomarkers: study of type-2 diabetes by cross-tissue analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 15, 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.Y., Loven J., Rahl P.B., et al. (2012). Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell 151, 56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Chen P., Aihara K., et al. (2015). Identifying early-warning signals of critical transitions with strong noise by dynamical network markers. Sci. Rep. 5, 17501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Wang X., Aihara K., et al. (2014). Early diagnosis of complex diseases by molecular biomarkers, network biomarkers, and dynamical network biomarkers. Med. Res. Rev. 34, 455–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wang Y., et al. (2016). Personalized characterization of diseases using sample-specific networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Li C., Xing Z., et al. (2010). Proteomic mining in the dysplastic liver of WHV/c-myc mice--insights and indicators for early hepatocarcinogenesis. FEBS J. 277, 4039–4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., et al. (2008). Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra K., Carvunis A.R., Ramesh S.K., et al. (2013). Integrative approaches for finding modular structure in biological networks. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 719–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J.J. (2009). New aspects of the role of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids in cell growth and cancer development. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Hu G., Wei G., et al. (2012). c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell 151, 68–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterreicher C.H., and Trauner M. (2012). Xenobiotic-induced liver injury and fibrosis. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 8, 571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C., Kumar C., Bohl S., et al. (2009). Comparative proteomic phenotyping of cell lines and primary cells to assess preservation of cell type-specific functions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahy D., Kaipainen A., Greene E.R., et al. (2010). Cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids: the neglected pathway in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 29, 723–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.B., Lee C.S., Jang J.H., et al. (2012). Phospholipase signalling networks in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 782–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi A., Ibanez M.R., Gatica A.E., et al. (2007). Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17685–17695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi A., Popescu V., Yang S., et al. (2010). The anti-tumorigenic properties of peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor alpha are arachidonic acid epoxygenase-mediated. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12840–12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland T., Tasan M., Charloteaux B., et al. (2014). A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell 159, 1212–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa R., Zhang W., Ge J., et al. (2016). Discovering a critical transition state from nonalcoholic hepatosteatosis to steatohepatitis by lipidomics and dynamical network biomarkers. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snelgrove R.J., Jackson P.L., Hardison M.T., et al. (2010). A critical role for LTA4H in limiting chronic pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation. Science 330, 90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L.Y., Deng N., Wang L.S., et al. (2007). Quantitative phosphoproteome profiling of Wnt3a-mediated signaling network: indicating the involvement of ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase M2 subunit phosphorylation at residue serine 20 in canonical Wnt signal transduction. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1952–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise N.D., Park Y.N., and Kojiro M. (2002). Dysplastic nodules and hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin. Liver Dis. 6, 497–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A., Schafer J., Kuhn K., et al. (2003). Tandem mass tags: a novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 75, 1895–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W.G., Ding X.Z., Talamonti M.S., et al. (2005). LTB4 stimulates growth of human pancreatic cancer cells via MAPK and PI-3 kinase pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden M.G. (2011). Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden M.G., Cantley L.C., and Thompson C.B. (2009). Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., and Dubois R.N. (2010). Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Huang Q., Liu Z.P., et al. (2011). NOA: a novel Network Ontology Analysis method. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Zhang W., Zeng T., et al. (2014). MCentridFS: a tool for identifying module biomarkers for multi-phenotypes from high-throughput data. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 2870–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woutersen R.A., Appel M.J., van Garderen-Hoetmer A., et al. (1999). Dietary fat and carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 443, 111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin D.C. (2001). Epoxygenase pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36059–36062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller K.I., Jegga A.G., Aronow B.J., et al. (2003). An integrated database of genes responsive to the Myc oncogenic transcription factor: identification of direct genomic targets. Genome Biol. 4, R69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng T., Zhang W., Yu X., et al. (2016). Big-data based edge biomarkers: study on dynamical drug sensitivity and resistance in individuals. Brief. Bioinform. 17, 576–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zeng T., Liu X., et al. (2015. a). Diagnosing phenotypes of single-sample individuals by edge biomarkers. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu K., Liu Z.P., et al. (2013). NARROMI: a noise and redundancy reduction technique improves accuracy of gene regulatory network inference. Bioinformatics 29, 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhao J., Hao J.K., et al. (2015. b). Conditional mutual inclusive information enables accurate quantification of associations in gene regulatory networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Zhou Y., Zhang X., et al. (2016). Part mutual information for quantifying direct associations in networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5130–5135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Dai J., Sheng Q.H., et al. (2007). A fully automated 2-D LC-MS method utilizing online continuous pH and RP gradients for global proteome analysis. Electrophoresis 28, 4311–4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.