Abstract

Background.

Children under 3 years of age may benefit from a double-dose of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (IIV4) instead of the standard-dose.

Methods.

We compared the only United States-licensed standard-dose IIV4 (0.25 mL, 7.5 µg hemagglutinin per influenza strain) versus double-dose IIV4 manufactured by a different process (0.5 mL, 15 µg per strain) in a phase III, randomized, observer-blind trial in children 6–35 months of age (NCT02242643). The primary objective was to demonstrate immunogenic noninferiority of the double-dose for all vaccine strains 28 days after last vaccination. Immunogenic superiority of the double-dose was evaluated post hoc. Immunogenicity was assessed in the per-protocol cohort (N = 2041), and safety was assessed in the intent-to-treat cohort (N = 2424).

Results.

Immunogenic noninferiority of double-dose versus standard-dose IIV4 was demonstrated in terms of geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio and seroconversion rate difference. Superior immunogenicity against both vaccine B strains was observed with double-dose IIV4 in children 6–17 months of age (GMT ratio = 1.89, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.64–2.17, B/Yamagata; GMT ratio = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.82–2.50, B/Victoria) and in unprimed children of any age (GMT ratio = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.59–2.13, B/Yamagata; GMT ratio = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.79–2.33, B/Victoria). Safety and reactogenicity, including fever, were similar despite the higher antigen content and volume of the double-dose IIV4. There were no attributable serious adverse events.

Conclusions.

Double-dose IIV4 may improve protection against influenza B in some young children and simplifies annual influenza vaccination by allowing the same vaccine dose to be used for all eligible children and adults.

Keywords: children, double-dose, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine.

Influenza has a high incidence and burden in children [1–4]. In particular, influenza B is reported to cause a disproportionate number of influenza-related deaths in children [5]. Routine vaccination of children against influenza is recommended in the United States [6] and other countries. Quadrivalent influenza vaccines containing 2 influenza A strains and 2 influenza B strains are increasingly used in vaccination programs to replace trivalent vaccines.

Inactivated influenza vaccines (IIVs) are administered to adults and children from 3 years of age at a dose of 0.5 mL, containing 15 µg of hemagglutinin (HA) per virus strain. In children under 3 years of age, the United States-licensed standard-dose is 0.25 mL, containing 7.5 µg of HA per virus strain. Both the 15 µg and 7.5 µg doses are available for this age group in some countries, including Canada, Brazil, Mexico, Finland, and the United Kingdom. The 7.5 µg dose was introduced in the 1970s to reduce reactogenicity, including febrile convulsions, associated with the whole virus vaccines available at the time [7–11]. However, young children mount a variable immune response to the 7.5 µg dose [12–14]. Currently available split virus vaccines are better tolerated than whole virus vaccines [10, 15, 16], questioning the practice of using the 7.5 µg dose with IIVs.

The inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (IIV4) manufactured in Quebec, Canada by GSK Vaccines is licensed at a double-dose (15 µg per antigen) for children from 6 months of age in Canada and Mexico, but it is currently only licensed for children 3 years of age and older in the United States. The only IIV4 licensed for use in children 6–35 months of age in the United States is Sanofi Pasteur’s Fluzone Quadrivalent in a standard-dose (7.5 µg per antigen). No other IIV is approved in the United States in this age group either because immunogenic noninferiority to Fluzone could not be demonstrated [17, 18] or because of excessive reactogenicity [19, 20].

If the double-dose vaccine could be administered in young children without adverse effects on tolerability, this age group may benefit from potentially improved immunogenicity. In this study, we describe a phase III study that compared the safety and immunogenicity of a double-dose IIV4 manufactured by GSK Vaccines with the United States-approved standard-dose IIV4 in children 6–35 months of age.

METHODS

This was a phase III, randomized, controlled, observer-blind, multicenter trial in children 6–35 months of age (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02242643). The trial was approved by independent ethics committees or institutional review boards, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines, ICH Harmonised Tripartite guideline for pediatric populations, and US regulatory requirements. Parents or legally acceptable representatives provided written informed consent.

Participants, Vaccines, and Study Design

Children in stable health were recruited in the United States and Mexico during the 2014–15 influenza season (Supplementary Appendix). The double-dose IIV4 (GSK Vaccines, Quebec, Canada) contained 15 μg HA of each of the 4 strains: A/California/7/2009 (A/H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012 (A/H3N2), B/Brisbane/60/2008 (B/Victoria), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (B/Yamagata). The standard-dose IIV4 (Fluzone Quadrivalent; Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA) contained 7.5 μg of HA of each of the same strains.

Children were randomized 1:1 to double-dose or standard-dose IIV4. Allocation to a study group at the investigator site was performed using an internet-based randomization system (SBIR). The randomization algorithm used a minimization procedure to balance the composition of treatment groups, accounting for age (6–17 and 18–35 months), center, and influenza vaccine priming status. The study aimed to enroll 40%–50% of children in the 6–17 months age group. Children were considered vaccine-primed if they had received 2 or more doses of influenza vaccine since July 1, 2010 or at least 1 dose of the 2013–14 influenza vaccine. Vaccine-primed children received a single dose on day 0. Vaccine-unprimed children received 1 dose on day 0 and another on day 28.

Study Endpoints

Blood for serologic testing was obtained on days 0 and 28 from primed children and on days 0 and 56 from unprimed children. The following parameters were derived from hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers: (1) geometric mean titer (GMT), (2) seroconversion rate (SCR), (3) seroprotection rate (SPR), and (4) mean geometric increase (MGI). Seroconversion rate was defined as the percentage of participants with either (1) prevaccination reciprocal HI titer <1:10 and a postvaccination reciprocal titer ≥1:40 or (2) prevaccination reciprocal titer ≥1:10 and at least a 4-fold increase in postvaccination reciprocal titer. Seroprotection rate was defined as the percentage of participants who attained reciprocal HI titers of ≥1:40. Mean geometric increase was defined as the geometric mean of the within-subject ratios of the postvaccination/prevaccination reciprocal HI titer.

Parents recorded solicited injection site and general symptoms on the day of vaccination and for the next 6 days. Spontaneously reported symptoms were recorded until 28 days after vaccination. Serious adverse events (SAEs), potential immune-mediated diseases, and medically attended adverse events were recorded until the final study contact on day 180. Monitoring for febrile seizures was carried out throughout the study.

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to demonstrate immunogenic noninferiority of the double-dose versus the standard-dose IIV4 28 days after completion of the vaccination course. Noninferiority criteria were met if, for each of the 4 vaccine strains, the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the GMT ratio (standard-dose/double-dose) was ≤1.5 and the upper limit of the 95% CI of the difference in SCR (standard-dose minus double-dose) was ≤10%.

If the primary objective was achieved, the secondary objective was to evaluate whether double-dose IIV4 produced an immune response against each of the vaccine strains that met Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) criteria, ie, the lower limit of the 95% CI of the SCR was ≥ 40% and the lower limit of the 95% CI of the SPR was ≥ c>70%. Additional secondary objectives were to (1) evaluate GMT, SPR, SCR, and MGI at 28 days after completion of the vaccination course, (2) describe the safety and reactogenicity of the vaccines, and (3) evaluate the relative risk of fever with double-dose versus standard-dose during the 2-day postvaccination period.

A post hoc evaluation was conducted to compare the immune response of the double-dose versus the standard-dose using CBER criteria conventionally applied to establish vaccine lot-to-lot consistency. Immunogenic superiority of the double-dose was concluded if the lower limit of the 95% CI of the GMT ratio (double-dose/standard-dose) was >1.5 and the lower limit of the 95% CI of the difference in SCR (double-dose minus standard-dose) was >10%.

Statistics

Enrollment of 1200 children per group (1020 evaluable subjects assuming an attrition rate of 15%) was planned to allow a global statistical power of 99% for the primary objective evaluation. The immunogenicity analysis was based on the per-protocol cohort and the safety analysis was based on the intent-to-treat cohort (Supplementary Appendix). Subgroup analyses according to age and priming status were conducted on the per-protocol cohort.

The overall type I error for the study was 5%. If the primary objective was met, the secondary objective of CBER criteria evaluation was tested to provide supportive evidence of immunogenicity. Calculation of 95% CIs is described in the Supplementary Appendix. The group GMT ratio was computed using an analysis of covariance model on the log-transformed titers. Analyses of immunogenicity excluded participants with missing or nonevaluable measurements at the postvaccination time point. Study power was calculated using PASS 2005 (Supplementary Appendix).

RESULTS

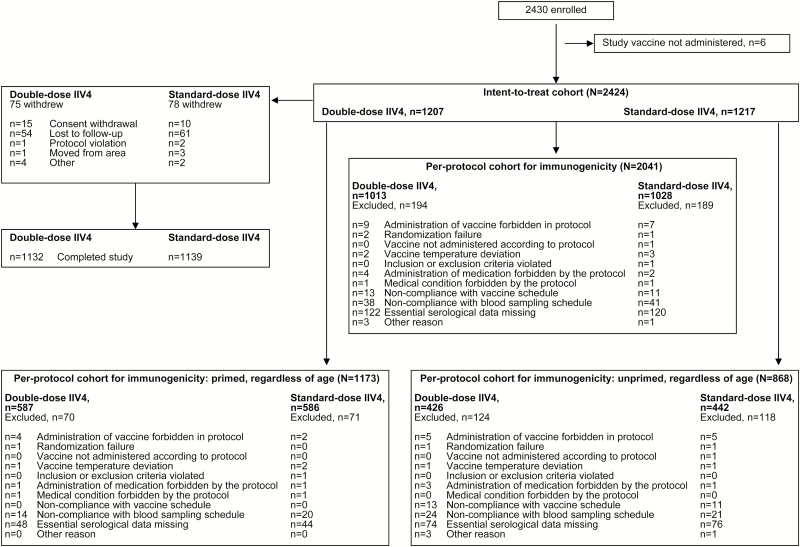

A total of 2424 and 2041 children were included in the intent-to-treat cohort and per-protocol cohort, respectively (Figure 1). Demographics were similar in both vaccine groups (Table 1). In the per-protocol cohort, 57.5% of children were vaccine-primed; mean age was 24.6 and 13.3 months for primed and unprimed children, respectively. Other demographic characteristics were similar in primed and unprimed children (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Participant disposition.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (Per-Protocol Cohort)

| All Children (Regardless Of Priming Status, 6–35 Months) | Primed Children (6–35 Months) | Unprimed Children (6–35 Months) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Double-Dose IIV4 N = 1013 | Standard-Dose IIV4 N = 1028 | Double-Dose IIV4 N = 587 | Standard-Dose IIV4 N = 586 | Double-Dose IIV4 N = 426 | Standard-Dose IIV4 N = 442 |

| Age at first vaccination, months, mean (SD) | 19.7 (8.7) | 19.9 (8.9) | 24.5 (6.2) | 24.8 (6.1) | 13.1 (7.2) | 13.5 (7.9) |

| Age 6–17 months, n (%) | 400 (39.5) | 401 (39.0) | 74 (12.6) | 69 (11.8) | 326 (76.5) | 332 (75.1) |

| <12 months, n (%) | 213 (21.0) | 226 (22.0) | 0 | 0 | 213 (50.0) | 226 (51.1) |

| Age 18–35 months, n (%) | 613 (60.5) | 627 (61.0) | 513 (87.4) | 517 (88.2) | 100 (23.5) | 110 (24.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 462 (45.6) | 496 (48.2) | 264 (45.0) | 283 (48.3) | 198 (46.5) | 213 (48.2) |

| Geographic ancestry, n (%) | ||||||

| Caucasian/European | 647 (63.9) | 667 (64.9) | 393 (67.0) | 400 (68.3) | 254 (59.6) | 267 (60.4) |

| African/African American | 143 (14.1) | 140 (13.6) | 89 (15.2) | 78 (13.3) | 54 (12.7) | 62 (14.0) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 23 (2.3) | 18 (1.8) | 15 (2.6) | 13 (2.2) | 8 (1.9) | 5 (1.1) |

| South East Asian | 17 (1.7) | 20 (1.9) | 11 (1.9) | 14 (2.4) | 6 (1.4) | 6 (1.4) |

| Other | 183 (18.1) | 183 (17.8) | 79 (13.5) | 81 (13.8) | 104 (24.4) | 102 (23.1) |

Abbreviatioins: IIV4, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine; N, number of participants included in analysis; n, number of participants in stated category; SD, standard deviation.

Immunogenicity

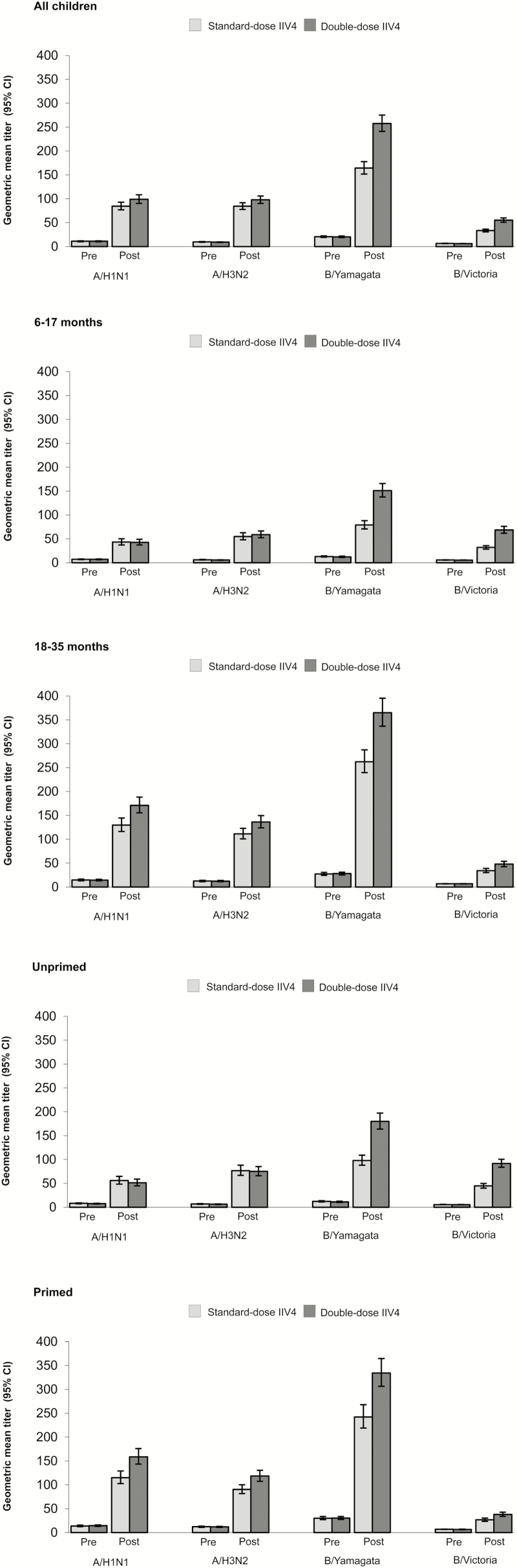

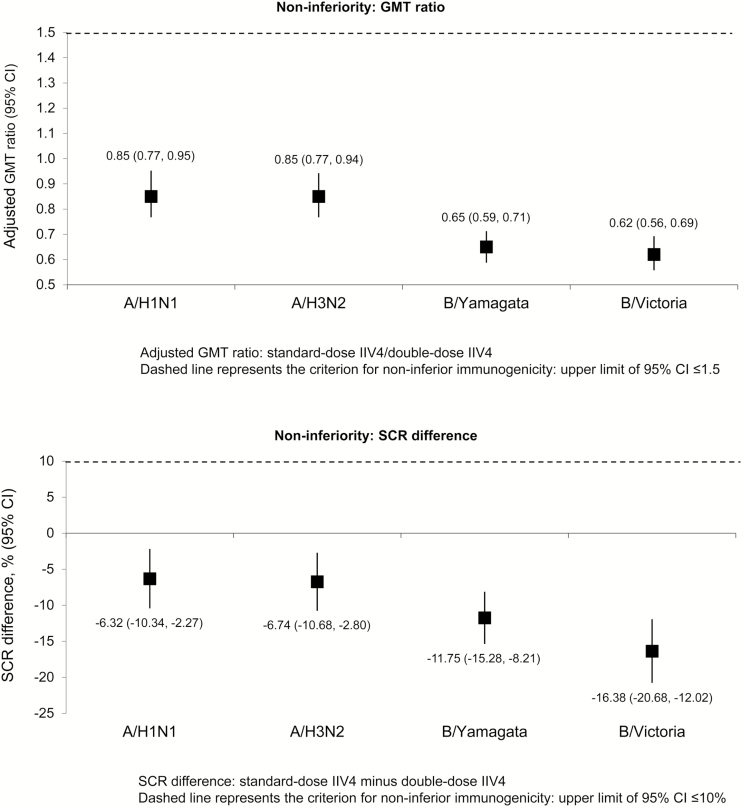

Both vaccines were immunogenic against all vaccine strains in terms of GMT values (Figure 2). Immunogenic noninferiority of the double-dose IIV4 versus the standard-dose IIV4 was demonstrated for all vaccine strains (Figure 3). Seroconversion rate, SPR, and MGI values were higher in the double-dose group compared with the standard-dose group in the whole study population (6–35 months of age, regardless of priming status; Table 2). The lower limit of the 95% CI for SCR was ≥40% for the double-dose IIV4 against all vaccine strains (Table 2), meeting CBER criteria for demonstration of adequate immunogenicity. For SPR, the lower limit of the 95% CI was ≥70% for all strains except B/Victoria (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Geometric mean titer for all vaccine strains in all children 6–35 months of age regardless of priming status and in each subgroup prevaccination and 28 days after completion of vaccination series (per-protocol cohort). CI, confidence interval; IIV4, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine.

Figure 3.

Noninferiority of the double-dose versus the standard-dose in all children 6–35 months of age regardless of priming status: geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio and difference in seroconversion rate (SCR) at 28 days after completion of vaccination series (per-protocol cohort). CI, confidence interval; IIV4, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine.

Table 2.

Immunogenicity Against Each Vaccine Strain at 28 Days After Completion of Vaccination Series in All Children 6–35 Months of Age Regardless of Priming Status (Per-Protocol Cohort)

| A/H1N1 | A/H3N2 | B/Yamagata | B/Victoria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value |

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 1013 | 98.8 (90.3–108.2) | 1013 | 97.7 (90.3–105.7) | 1013 | 257.5 (240.9–275.3) | 1013 | 55.1 (50.8–59.8) |

| Standard-dose | 1028 | 84.4 (76.9–92.6) | 1028 | 84.3 (77.6–91.6) | 1028 | 164.2 (151.8–177.6) | 1028 | 33.4 (30.6–36.4) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 972 | 73.7 (70.8–76.4) | 972 | 76.1 (73.3–78.8) | 974 | 85.5 (83.2–87.7) | 973 | 64.9 (61.8–67.9) |

| Standard-dose | 980 | 67.3 (64.3–70.3) | 980 | 69.4 (66.4–72.3) | 980 | 73.8 (70.9–76.5) | 980 | 48.5 (45.3–51.6) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 1013 | 80.4 (77.8–82.8) | 1013 | 82.2 (79.7–84.5) | 1013 | 97.0 (95.8–98.0) | 1013 | 66.0 (63.0–69.0) |

| Standard-dose | 1028 | 75.4 (72.6–78.0) | 1028 | 77.8 (75.2–80.3) | 1028 | 88.6 (86.5–90.5) | 1028 | 49.8 (46.7–52.9) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 972 | 9.0 (8.4–9.7) | 972 | 10.7 (10.0–11.6) | 974 | 12.7 (11.7–13.7) | 973 | 8.7 (8.1–9.4) |

| Standard-dose | 980 | 7.7 (7.1–8.3) | 980 | 8.9 (8.2–9.7) | 980 | 8.1 (7.5–8.8) | 980 | 5.4 (5.0–5.8) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DIL, dilution; GMT, geometric mean titer; MGI, mean geometric increase; N, number of participants included in analysis; SCR, seroconversion rate; SPR, seroprotection rate.

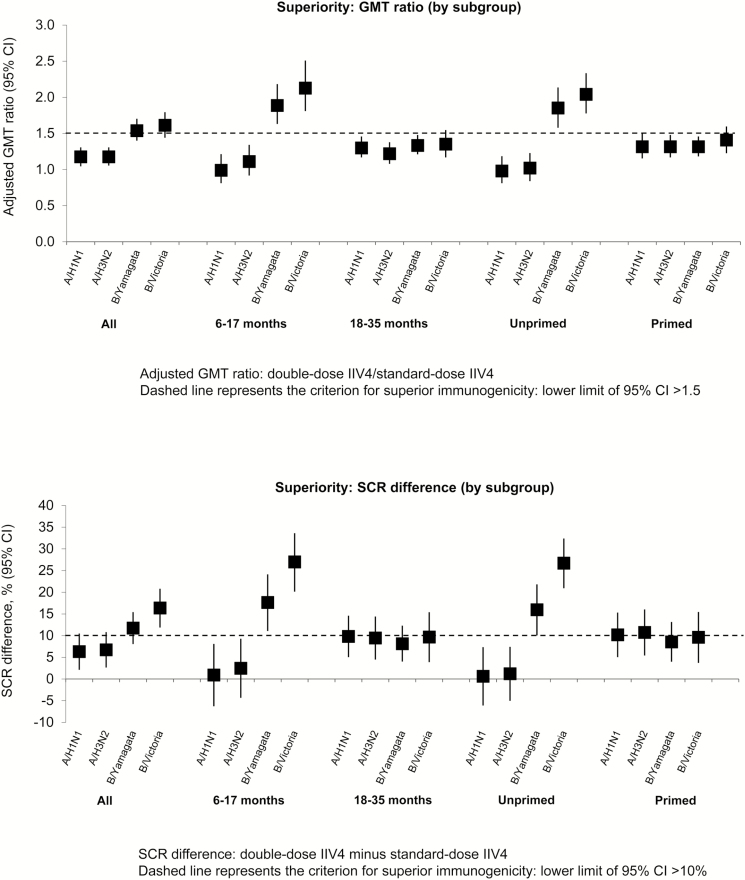

Immunogenicity was higher in the double-dose group compared with the standard-dose group, particularly against vaccine B strains in children 6–17 months of age and unprimed children (Table 3; Figure 2). When the unprimed group was further evaluated by age, it could be seen that the main difference between vaccines occurred in children 6–17 months of age. These observations prompted us to perform the post hoc evaluation comparing the immune response elicited by the vaccines in the whole study population and according to age group and priming status. The analysis indicated superior immunogenicity of the double-dose IIV4 against both vaccine B strains in children 6–17 months of age and all unprimed children. In children 6–17 months of age, the GMT ratio was 1.89 (95% CI, 1.64–2.17) for B/Yamagata and 2.13 (95% CI, 1.82–2.50) for B/Victoria (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Corresponding values in all unprimed children were 1.85 (95% CI, 1.59–2.13) and 2.04 (95% CI, 1.79–2.33). Superior immunogenicity of the double-dose was also observed for the same groups in terms of SCR difference (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of Immunogenicity of the Double-Dose Versus the Standard-Dose According to Age and Priming Status at 28 Days After Completion of Vaccination Series (Per-Protocol Cohort)

| A/H1N1 | A/H3N2 | B/Yamagata | B/Victoria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value |

| 6–17 months (regardless of priming status) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 400 | 42.7 (37.1–49.0) | 400 | 58.9 (52.2–66.4) | 400 | 151.0 (137.4–165.9) | 400 | 68.7 (61.8–76.3) |

| Standard-dose | 401 | 43.2 (37.3–50.0) | 401 | 54.8 (47.9–62.7) | 401 | 79.1 (70.9–88.1) | 401 | 31.9 (28.4–35.7) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double dose | 400 | 61.3 (56.3–66.1) | 400 | 70.3 (65.5–74.7) | 400 | 94.3 (91.5–96.3) | 400 | 78.3 (73.9–82.2) |

| Standard-dose | 401 | 59.9 (54.9–64.7) | 401 | 67.8 (63.0–72.4) | 401 | 77.6 (73.2–81.5) | 401 | 51.4 (46.4–56.4) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 376 | 58.5 (53.3–63.5) | 376 | 69.1 (64.2–73.8) | 376 | 79.5 (75.1–83.5) | 376 | 77.4 (72.8–81.5) |

| Standard-dose | 375 | 57.6 (52.4–62.7) | 375 | 66.7 (61.6–71.4) | 375 | 61.9 (56.7–66.8) | 375 | 50.4 (45.2–55.6) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 376 | 6.0 (5.3–6.8) | 376 | 10.2 (9.0–11.6) | 376 | 12.3 (10.7–14.3) | 376 | 12.3 (11.0–13.8) |

| Standard-dose | 375 | 6.1 (5.2–7.1) | 375 | 8.8 (7.7–10.2) | 375 | 6.1 (5.3–7.0) | 375 | 5.7 (5.1–6.4) |

| 18–35 months (regardless of priming status) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 613 | 170.9 (155.2–188.3) | 613 | 136.0 (123.7–149.6) | 613 | 364.8 (336.7–395.3) | 613 | 47.8 (42.6–53.6) |

| Standard-dose | 627 | 129.6 (116.3–144.3) | 627 | 111.1 (100.6–122.7) | 627 | 262.1 (239.3–287.1) | 627 | 34.4 (30.4–38.8) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 613 | 92.8 (90.5–94.7) | 613 | 90.0 (87.4–92.3) | 613 | 98.9 (97.7–99.5) | 613 | 58.1 (54.1–62.0) |

| Standard-dose | 627 | 85.3 (82.3–88.0) | 627 | 84.2 (81.1–87.0) | 627 | 95.7 (93.8–97.1) | 627 | 48.8 (44.8–52.8) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 596 | 83.2 (80.0–86.1) | 596 | 80.5 (77.1–83.6) | 598 | 89.3 (86.5–91.7) | 597 | 57.0 (52.9–61.0) |

| Standard-dose | 605 | 73.4 (69.7–76.9) | 605 | 71.1 (67.3–74.7) | 605 | 81.2 (77.8–84.2) | 605 | 47.3 (43.2–51.3) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 596 | 11.7 (10.7–12.8) | 596 | 11.1 (10.1–12.1) | 598 | 12.9 (11.8–14.0) | 597 | 7.0 (6.4–7.7) |

| Standard-dose | 605 | 8.9 (8.1–9.8) | 605 | 9.0 (8.2–9.9) | 605 | 9.7 (8.9–10.6) | 605 | 5.2 (4.7–5.7) |

| Primed (regardless of age) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 587 | 158.8 (143.3–176.0) | 587 | 118.4 (107.5–130.3) | 587 | 334.3 (306.4–364.7) | 587 | 38.1 (34.0–42.8) |

| Standard-dose | 586 | 115.0 (102.6–128.9) | 586 | 90.4 (81.8–100.0) | 586 | 242.2 (219.1–267.7) | 586 | 26.7 (23.6–30.3) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 587 | 90.6 (88.0–92.9) | 587 | 87.2 (84.2–89.8) | 587 | 98.1 (96.7–99.1) | 587 | 49.4 (45.3–53.5) |

| Standard-dose | 586 | 82.1 (78.7–85.1) | 586 | 80.2 (76.7–83.4) | 586 | 93.7 (91.4–95.5) | 586 | 40.1 (36.1–44.2) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 570 | 80.5 (77.0–83.7) | 570 | 77.9 (74.3–81.2) | 572 | 86.5 (83.5–89.2) | 571 | 48.0 (43.8–52.2) |

| Standard-dose | 563 | 70.3 (66.4–74.1) | 563 | 67.1 (63.1–71.0) | 563 | 78.0 (74.3–81.3) | 563 | 38.4 (34.3–42.5) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 570 | 10.9 (10.0–12.0) | 570 | 10.0 (9.1–10.9) | 572 | 10.7 (9.9–11.6) | 571 | 5.6 (5.1–6.1) |

| Standard-dose | 563 | 8.5 (7.7–9.3) | 563 | 7.6 (6.9–8.3) | 563 | 8.2 (7.6–8.9) | 563 | 4.0 (3.6–4.4) |

| Unprimed (regardless of age) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 426 | 51.4 (44.7–59.1) | 426 | 75.0 (66.0–85.3) | 426 | 179.8 (163.7–197.4) | 426 | 91.7 (83.8–100.3) |

| Standard-dose | 442 | 56.0 (48.4–64.8) | 442 | 76.8 (66.9–88.3) | 442 | 98.1 (88.1–109.3) | 442 | 44.8 (40.1–50.0) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 426 | 66.2 (61.5–70.7) | 426 | 75.4 (71.0–79.4) | 426 | 95.5 (93.1–97.3) | 426 | 89.0 (85.6–91.8) |

| Standard-dose | 442 | 66.5 (61.9–70.9) | 442 | 74.7 (70.3–78.7) | 442 | 81.9 (78.0–85.4) | 442 | 62.7 (58.0–67.2) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 402 | 63.9 (59.0–68.6) | 402 | 73.6 (69.0–77.9) | 402 | 84.1 (80.1–87.5) | 402 | 88.8 (85.3–91.7) |

| Standard-dose | 417 | 63.3 (58.5–67.9) | 417 | 72.4 (67.9–76.7) | 417 | 68.1 (63.4–72.6) | 417 | 62.1 (57.3–66.8) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 402 | 6.9 (6.1–7.8) | 402 | 11.8 (10.4–13.4) | 402 | 16.0 (13.9–18.5) | 402 | 16.2 (14.8–17.8) |

| Standard-dose | 417 | 6.8 (5.9–7.8) | 417 | 11.2 (9.7–12.9) | 417 | 8.0 (6.9–9.3) | 417 | 8.0 (7.2–8.8) |

| Unprimed (6–17 months) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 326 | 36.2 (31.3–41.9) | 326 | 56.7 (49.7–64.8) | 326 | 146.8 (132.5–162.7) | 326 | 84.6 (76.7–93.3) |

| Standard-dose | 332 | 38.0 (32.5–44.4) | 332 | 54.1 (46.6–62.7) | 332 | 71.1 (63.6–79.4) | 332 | 35.5 (31.5–40.0) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 326 | 57.4 (51.8–62.8) | 326 | 68.7 (63.4–73.7) | 326 | 94.2 (91.0–96.5) | 326 | 87.4 (83.3–90.8) |

| Standard-dose | 332 | 57.2 (51.7–62.6) | 332 | 68.4 (63.1–73.3) | 332 | 75.9 (70.9–80.4) | 332 | 55.1 (49.6–60.6) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 304 | 54.9 (49.2–60.6) | 304 | 68.4 (62.9–73.6) | 304 | 79.3 (74.3–83.7) | 304 | 87.2 (82.9–90.7) |

| Standard-dose | 309 | 55.0 (49.3–60.7) | 309 | 68.0 (62.4–73.1) | 309 | 58.9 (53.2–64.4) | 309 | 54.4 (48.6–60.0) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 304 | 5.5 (4.7–6.3) | 304 | 10.3 (8.9–11.9) | 304 | 12.8 (10.7–15.1) | 304 | 15.7 (14.0–17.6) |

| Standard-dose | 309 | 5.5 (4.6–6.5) | 309 | 9.1 (7.7–10.6) | 309 | 5.6 (4.7–6.6) | 309 | 6.5 (5.8–7.3) |

| Unprimed (18–35 months) | ||||||||

| GMT, 1/DIL (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 100 | 161.7 (125.9–207.7) | 100 | 187.0 (143.6–243.6) | 100 | 347.7 (296.3–407.9) | 100 | 119.2 (96.8–146.7) |

| Standard-dose | 110 | 180.9 (141.0–232.1) | 110 | 222.0 (173.3–284.4) | 110 | 260.0 (217.5–310.8) | 110 | 90.5 (73.2–111.8) |

| SPR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 100 | 95.0 (88.7–98.4) | 100 | 97.0 (91.5–99.4) | 100 | 100 (96.4–100) | 100 | 94.0 (87.4–97.8) |

| Standard-dose | 110 | 94.5 (88.5–98.0) | 110 | 93.6 (87.3–97.4) | 110 | 100 (96.7–100) | 110 | 85.5 (77.5–91.5) |

| SCR, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 98 | 91.8 (84.5–96.4) | 98 | 89.8 (82.0–95.0) | 98 | 99.0 (94.4–100) | 98 | 93.9 (87.1–97.7) |

| Standard-dose | 108 | 87.0 (79.2–92.7) | 108 | 85.2 (77.1–91.3) | 108 | 94.4 (88.3–97.9) | 108 | 84.3 (76.0–90.6) |

| MGI (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Double-dose | 98 | 13.9 (11.6–16.8) | 98 | 18.0 (14.1–23.1) | 98 | 32.5 (26.3–40.1) | 98 | 18.0 (15.3–21.2) |

| Standard-dose | 108 | 12.4 (10.2–15.1) | 108 | 20.7 (15.6–27.4) | 108 | 22.8 (18.4–28.3) | 108 | 14.2 (11.9–16.8) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DIL, dilution; GMT, geometric mean titer; MGI, mean geometric increase; N, number of participants included in analysis; SCR, seroconversion rate; SPR, seroprotection rate.

Figure 4.

Comparison of immunogenicity of the double-dose versus the standard-dose in all children 6–35 months of age regardless of priming status and in each subgroup: geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio and difference in seroconversion rate (SCR) at 28 days after completion of vaccination series (per-protocol cohort). CI, confidence interval; IIV4, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine.

Safety and Reactogenicity

Pain was the most common solicited injection site symptom, occurring in approximately 40% of children in both vaccine groups; severe (grade 3) pain occurred in 2.9% (95% CI, 2.0–4.1) and 1.7% (95% CI, 1.0–2.6) of children with the double-dose and standard-dose, respectively (Table 4). Fever (38.0°C) was reported in approximately 8% of children up to 7 days postvaccination; fever >39.0°C occurred in approximately 2% of children (Table 4). During the 2-day postvaccination period (days 0–1), the incidence of fever (≥38.0°C) was similar in both groups (Table 4), and the relative risk (double-dose/standard-dose) was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.62–1.52; P = .9777). Twenty-two SAEs occurred in the double-dose group and 21 in the standard-dose group (Table 4), none considered related to vaccination. Febrile seizure was reported in 5 children in the double-dose group and in 4 children in the standard-dose group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Safety Outcomes Reported Throughout the Study (Intent-to-Treat Cohort)

| Double-Dose IIV4 N = 1207a | Standard-Dose IIV4 N = 1217a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | No. Patients With Symptom | % (95% CI) | No. Patients With Symptom | % (95% CI) |

| Solicitedb injection site symptoms during 7-day postvaccination period | ||||

| Pain | 509 | 44.0 (41.1–46.9) | 462 | 40.1 (37.3–43.0) |

| Grade 3c | 34 | 2.9 (2.0–4.1) | 19 | 1.7 (1.0–2.6) |

| Redness | 16 | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | 16 | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) |

| Grade 3c | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Swelling | 11 | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | 5 | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) |

| Grade 3c | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Solicited general symptoms during 7-day postvaccination period | ||||

| Drowsiness | 471 | 40.6 (37.8–43.5) | 471 | 40.9 (38.0–43.8) |

| Grade 3c | 36 | 3.1 (2.2–4.3) | 34 | 3.0 (2.1–4.1) |

| Fever (≥38.0°C) | 91 | 7.9 (6.4–9.6) | 86 | 7.5 (6.0–9.1) |

| >39.0°C | 25 | 2.2 (1.4–3.2) | 17 | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) |

| Irritability/fussiness | 630 | 54.4 (51.4–57.3) | 582 | 50.5 (47.6–53.4) |

| Grade 3c | 61 | 5.3 (4.0–6.7) | 45 | 3.9 (2.9–5.2) |

| Loss of appetite | 391 | 33.7 (31.0–36.5) | 385 | 33.4 (30.7–36.2) |

| Grade 3c | 26 | 2.2 (1.5–3.3) | 19 | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) |

| Unsolicited (spontaneously reported) symptoms during 28-day postvaccination period | ||||

| All | 549 | 45.5 (42.6–48.3) | 537 | 44.1 (41.3–47.0) |

| Grade 3c | 70 | 5.8 (4.5–7.3) | 75 | 6.2 (4.9–7.7) |

| Related to vaccine | 71 | 5.9 (4.6–7.4) | 71 | 5.8 (4.6–7.3) |

| Fever reported during 2-day postvaccination period | ||||

| All (≥38.0°C) | 42 | 3.6 (2.6–4.9) | 43 | 3.7 (2.7–5.0) |

| Febrile seizured during entire study period | ||||

| All | 5 | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) | 4 | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) |

| Medically attended evente during entire study period | ||||

| All | 727 | 60.2 (57.4–63.0) | 719 | 59.1 (56.3–61.9) |

| Potential immune-mediated disease during entire study periodf | ||||

| All | 1g | 0.1 (0.0–0.5) | 1g | 0.1 (0.0–0.5) |

| Serious adverse event during entire study periodh | ||||

| All | 22 | 1.8 (1.1–2.7) | 21 | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IIV4, inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine; N, number of participants included in analysis.

aFor solicited injection site and general symptoms, only children for whom diary cards were returned are included (injection site symptoms: N = 1156 for double-dose IIV4 and N = 1151 for standard-dose IIV4; general symptoms: N = 1159 for double-dose IIV4 and N = 1152 for standard-dose IIV4).

bAll solicited injection-site symptoms were considered related to vaccination.

cGrade 3 events were defined as follows: pain: child cried when the limb was moved or the limb was spontaneously painful; redness and swelling: >100 mm surface diameter; drowsiness and irritability/fussiness: prevented normal activity; loss of appetite: did not eat at all; spontaneously reported symptom: prevented normal activity.

dIn the double-dose group, seizures occurred 5, 50, 88, 106, and 168 days after the first vaccine dose. In the standard-dose group, 1 seizure occurred 178 days after the first vaccine dose and the others 39, 74, and 80 days after the second vaccine dose. All children recovered, and none of the seizures was considered by the investigator to be related to vaccination.

eHospitalization, emergency room visit, medical practitioner visit.

fAutoimmune diseases and other inflammatory and/or neurologic disorders that may or may not have an autoimmune etiology, according to a protocol-specified list or investigators’ judgment.

gKawasaki’s disease in the double-dose group and erythema multiforme in the standard-dose group, neither related to vaccination.

hSerious adverse events were defined as any untoward medical occurrence that results in death, is life-threatening, requires hospitalization or prolongs hospitalization, or results in disability or incapacity.

There was a modest increase in reactogenicity with regard to general symptoms in children 6–17 months of age compared with those aged 18–35 months with both the double-dose and standard-dose vaccines. With the double-dose vaccine, the fold-difference between the younger and older age groups ranged from 1.3 for loss of appetite to 2.7 for fever ≥38.0°C. With the standard-dose, the fold-difference ranged from 1.2 for loss of appetite to 1.6 for drowsiness and fever ≥38.0°C. The difference between age groups was unlikely to be due to chance because, in general, 95% CIs did not overlap. However, there were overlapping 95% CIs and thus no apparent age group differences with the standard-dose vaccine for fever ≥38.0°C and loss of appetite.

DISCUSSION

The introduction of IIV4 provides an opportunity to review long-accepted practices in administration of influenza vaccines. Since the 1970s, the standard-dose of IIVs in children less than 3 years of age has been 7.5 µg per antigen, half the dose given to older children and adults. The lower dose was intended to reduce reactogenicity and febrile convulsions observed with the whole virus vaccines that were in use at the time [7–11]. However, young children mount a variable immune response to this lower dose, especially against vaccine B strains [12–14]. In particular, vaccine-naive children less than 3 years of age mount a lower immune response compared with older or vaccine-primed children [14, 21–23]. The immune response in this vulnerable group could be improved by a change in practice to administer the double-dose, ie, same dose as used for children 3 years of age and above, and for adults. Increasing the immunogenicity of IIVs for young children is expected to improve their effectiveness, because the postvaccination HI antibody titer is inversely related to the risk of illness [24, 25]. However, there is controversy regarding the HI antibody titer necessary to offer high-level effectiveness [24, 25].

In the present study, both the double-dose and the standard-dose IIV4s were immunogenic against all vaccine strains in primed and unprimed children 6–35 months of age. The primary objective of the study—to fulfill US licensure criteria by demonstrating immunogenic noninferiority of the investigational IIV4 to a licensed IIV4 and acceptable safety of the investigational IIV4—was achieved. Most children receiving the double-dose IIV4 seroconverted (SCRs, 64.9%–85.5%), and most children achieved seroprotection (SPRs, 66.0%–97.0%). Similar immune responses have been achieved with the double-dose IIV4 in children of the same age in small studies conducted in 3 prior seasons [26–28].

Greater antibody responses were observed with the double-dose IIV4 compared with the standard-dose, prompting us to perform a post hoc analysis to evaluate whether the double-dose elicited a superior immune response in terms of the CBER criteria usually applied to establish lot-to-lot consistency of influenza vaccines. In this analysis, the double-dose IIV4 did not reach superiority to the standard-dose in the overall population, the older age group (18–35 months), or previously primed children. However, in the younger age group (6–17 months) and in all unprimed children, the double-dose IIV4 met the applied superiority immune response criteria compared with the standard-dose against the B strains. It should be noted that the unprimed group was predominantly 6–17 months of age.

Several previous studies have compared the HI antibody response elicited by a double-dose versus a standard-dose IIV. The results of the present large phase III study contrast with those of a phase II study comparing GSK’s double-dose IIV4 with the United States-approved standard-dose inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (IIV3) (the corresponding IIV3 to the licensed IIV4 comparator used in the present study) [26]. In the phase II study, the immune response with the double-dose and the standard-dose was similar against the strains common to both vaccines, but the sample size was too small to reliably detect differential immunogenicity against the vaccine B strains, especially in children 6–17 months of age [26]. Two other small studies compared the immunogenicity of the United States-approved IIV3 administered as a standard or double-dose to young children in different years, with contrasting results [21, 29]. A 2008–09 trial found that a double-dose IIV3 elicited a higher immune response than a standard-dose in vaccine-unprimed children 6–23 months of age, reaching statistical significance in children 6–11 months of age for 2 of 3 vaccine strains [21]. However, a 2010–12 trial found no difference in immunogenicity between standard-dose versus double-dose IIV3s in unprimed children [29]. This prior experience highlights the necessity for trials of adequate size to reliably establish treatment benefit, and it suggests that observations made in 1 year may not be repeated in other years, because the baseline immunity of young children may vary. Furthermore, the dose effect on immunogenicity among IIVs may differ according to their manufacturing process [23, 26].

In the present study, the double-dose and standard-dose IIV4s had a similar reactogenicity profile despite the higher antigen content and volume of the double-dose. Injection site symptoms, including pain, occurred at a similar rate in both groups. There was no difference in the rate of fever over the 2-day postvaccination period between the 2 groups. Febrile seizures occurred at a similar rate in both groups, none were reported within 2 days of vaccination, and none were considered related to the vaccine. The finding that the higher antigen dose and volume in this study did not adversely affect tolerability in children confirms previous findings from studies comparing reactogenicity and safety of double-dose versus standard-dose IIVs [21–23, 26, 29], and IIV4s versus IIV3s [26, 27, 30–32].

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a double-dose IIV4 may afford greater protection in young children against influenza B. Increased protection against influenza B, a potentially serious and life-threatening illness particularly in young children [33], would be a beneficial clinical outcome. Use of the same vaccine dose for all eligible ages would also simplify the annual influenza vaccine campaign and reduce cost [34] and logistic complexity. This study provides evidence to support a change in clinical practice to use a double-dose IIV4 (15 µg per antigen) in all children 6 months of age and older, once that dosing for a vaccine product has been approved.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Journal of The Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society online.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We are indebted to the participating study volunteers and their parents, clinicians, nurses, and laboratory technicians at the study sites. In particular, we thank Christopher Chambers, Larkin Wadsworth, Wendy Daly, William Johnston, Michael Levin, William Douglas, Agnes Schultz, Edward Zissman, Terry Poling, Paul Bernhardson, Brad Brabec, Stephen Russel, and Mary Tipton who provided support and cared for study participants. We thank the teams of GSK Vaccines, in particular, Silvija Jarnjak, Arshad Amanullah, Els Praet, and Rafik Bekkat-Berkani. Finally, we thank Mary L. Greenacre (An Sgriobhadair, UK, on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for providing medical writing services and Bruno Dumont and Véronique Gochet (Business and Decision Life Sciences, on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination.

Author contributions. All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis of the study, interpretation of the study, and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Financial support. This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA paid for all costs associated with the development of this manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. V. K. J., L. W., and P. L. were employed by the GSK group of companies at the time of the study. V. K. J. is currently employed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. L. W. is currently employed by Merck Research Laboratory. P. L. is currently employed by Pfizer. O. O.-A., J. S., V. C., and B. L. I. are currently employed by the GSK group of companies. V. K. J., L. W., O. O.-A., P. L., and B. L. I. currently hold shares in the GSK group of companies. J. B. D. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study, and reports grants and others from the GSK group of companies, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and MedImmune for consultancy services, outside the submitted work. M. L. L. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study. N. P. K. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study, and grants from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, Pfizer, Protein Science, MedImmune, Merck & Co, and Nuron Biotech, outside the submitted work. B. L. H. reports payments and nonfinancial support from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study. J. S. H. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study. A. C. M. reports payments from the GSK group of companies, during the conduct of the study.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. O’Brien MA, Uyeki TM, Shay DK, et al. Incidence of outpatient visits and hospitalizations related to influenza in infants and young children. Pediatrics 2004; 113:585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Izurieta HS, Thompson WW, Kramarz P, et al. Influenza and the rates of hospitalization for respiratory disease among infants and young children. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 2007; 25:5086–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bourgeois FT, Valim C, Wei JC, et al. Influenza and other respiratory virus-related emergency department visits among young children. Pediatrics 2006; 118:e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza-associated pediatric deaths–United States, September 2010-August 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:1233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Olsen SJ, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2015–16 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:818–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wright PF, Dolin R, La Montagne JR. From the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, the Center for Disease Control, and the Bureau of Biologics of the Food and Drug Administration. Summary of clinical trials of influenza vaccines–II. J Infect Dis 1976; 134:633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright PF, Thompson J, Vaughn WK, et al. Trials of influenza A/New Jersey/76 virus vaccine in normal children: an overview of age-related antigenicity and reactogenicity. J Infect Dis 1977; 136(Suppl):S731–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wright PF, Vaughn WK, Thompson J, et al. Inactivated influenza A/New Jersey/76 vaccines in children: results of a multi-center trial. Dev Biol Stand 1977; 39:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gross PA, Ennis FA, Gaerlan PF, et al. A controlled double-blind comparison of reactogenicity, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of whole-virus and split-product influenza vaccines in children. J Infect Dis 1977; 136:623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gross PA. Reactogenicity and immunogenicity of bivalent influenza vaccine in one- and two-dose trials in children: a summary. J Infect Dis 1977; 136(Suppl):S616–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Englund JA, Walter EB, Gbadebo A, et al. Immunization with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in partially immunized toddlers. Pediatrics 2006; 118:e579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walter EB, Neuzil KM, Zhu Y, et al. Influenza vaccine immunogenicity in 6- to 23-month-old children: are identical antigens necessary for priming? Pediatrics 2006; 118:e570–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walter EB, Rajagopal S, Zhu Y, et al. Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) immunogenicity in children 6 through 23 months of age: do children of all ages respond equally? Vaccine 2010; 28:4376–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bernstein DI, Zahradnik JM, DeAngelis CJ, Cherry JD. Clinical reactions and serologic responses after vaccination with whole-virus or split-virus influenza vaccines in children aged 6 to 36 months. Pediatrics 1982; 69:404–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernstein DI, Zahradnik JM, DeAngelis CJ, Cherry JD. Influenza immunization in children and young adults: clinical reactions and total and IgM antibody responses after immunization with whole-virus or split-product influenza vaccines. Am J Dis Child 1982; 136:513–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baxter R, Jeanfreau R, Block SL, et al. A Phase III evaluation of immunogenicity and safety of two trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines in US children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nolan T, Bravo L, Ceballos A, et al. Enhanced and persistent antibody response against homologous and heterologous strains elicited by a MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccine in infants and young children. Vaccine 2014; 32:6146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li-Kim-Moy J, Booy R. The manufacturing process should remain the focus for severe febrile reactions in children administered an Australian inactivated influenza vaccine during 2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2016; 10:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brady RC, Hu W, Houchin VG, et al. Randomized trial to compare the safety and immunogenicity of CSL Limited’s 2009 trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine to an established vaccine in United States children. Vaccine 2014; 32:7141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skowronski DM, Hottes TS, Chong M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of dose response to influenza vaccine in children aged 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics 2011; 128:e276–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langley JM, Vanderkooi OG, Garfield HA, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of 2 dose levels of a thimerosal-free trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine in children aged 6–35 months: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pavia-Ruz N, Angel Rodriguez Weber M, Lau YL, et al. A randomized controlled study to evaluate the immunogenicity of a trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine at two dosages in children 6 to 35 months of age. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9:1978–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Black S, Nicolay U, Vesikari T, et al. Hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers as a correlate of protection for inactivated influenza vaccines in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:1081–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng S, Fang VJ, Ip DK, et al. Estimation of the association between antibody titers and protection against confirmed influenza virus infection in children. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:1320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang L, Chandrasekaran V, Domachowske JB, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in US children 6–35 months of age during 2013–2014: results from a phase II randomized trial. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016; 5:170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langley JM, Wang L, Aggarwal N, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine administered intramuscularly to children 6 to 35 months of age in 2012–2013: a randomized, double blind, controlled, multi-centre, multi-country, clinical trial. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014; 4:242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Langley JM, Carmona Martinez A, Chatterjee A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine candidate: a phase III randomized controlled trial in children. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:544–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halasa NB, Gerber MA, Berry AA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of full-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) compared with half-dose TIV administered to children 6 through 35 months of age. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2015; 4:214–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greenberg DP, Robertson CA, Landolfi VA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children 6 months through 8 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenberg DP, Robertson CA, Noss MJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine compared to licensed trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in adults. Vaccine 2013; 31:770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Domachowske JB, Pankow-Culot H, Bautista M, et al. A randomized trial of candidate inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine versus trivalent influenza vaccines in children aged 3–17 years. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:1878–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paddock CD, Liu L, Denison AM, et al. Myocardial injury and bacterial pneumonia contribute to the pathogenesis of fatal influenza B virus infection. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine for Children Program (VFC). CDC Vaccine Price List. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/awardees/vaccine-management/price-list/ Accessed 8 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.