Abstract

The tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) is metabolically converted to 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in a reaction which is both stereoselective and reversible. NNAL is also a lung carcinogen, with both (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL inducing a high incidence of lung tumours in rats. Both NNAL and NNK undergo metabolic activation to intermediates which react with DNA to form pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts, respectively. DNA adduct formation by NNAL and NNK is an important step in their mechanisms of carcinogenesis. In this study, we quantified both pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts in the lung of rats treated with 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL or (S)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 and 70 weeks. In (R)-NNAL-treated rats, the pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl phosphate adducts were 4530–6920 fmol/mg DNA and 46–175 fmol/mg DNA, accounting for 45–51% and 0.3–1% of the total measured DNA phosphate and base adducts, respectively. In (S)-NNAL-treated rats, the two types of phosphate adducts were 3480–4180 fmol/mg DNA and 1180–4650 fmol/mg DNA, accounting for 30–36% and 11–38% of the total adducts, respectively. Distinct patterns of adduct formation were observed, with higher levels of NNAL-derived pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts and lower levels of NNK-derived pyridyloxobutyl phosphate adducts in the (R)-NNAL treatment group than the (S)-NNAL group. The persistence and increase over time of certain pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts over the course of the study suggest that these adducts could be useful biomarkers of chronic exposure to NNAL and NNK. The results of this study provide important new information regarding DNA damage by NNAL and NNK, and contribute to understanding mechanisms of tobacco-related carcinogenesis.

Introduction

The tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK, 1, Figure 1) is a potent pulmonary carcinogen in laboratory animals and, together with N′-nitrosonornicotine, is classified as a human carcinogen (Group 1) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (1). NNK is converted through carbonyl reduction to its metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL, 2, Figure 1) in various in vitro and in vivo biological systems (2,3). NNAL is also a potent lung carcinogen (2,4). Both NNK and NNAL are bioactivated upon cytochrome P450-catalysed hydroxylation to form reactive intermediates, which react with DNA to form adducts, a key step in determining the carcinogenic properties of NNK and NNAL (3,5). Therefore, measurement of DNA adduct formation by NNK and NNAL potentially can provide important insights into mechanisms of tobacco-associated cancer.

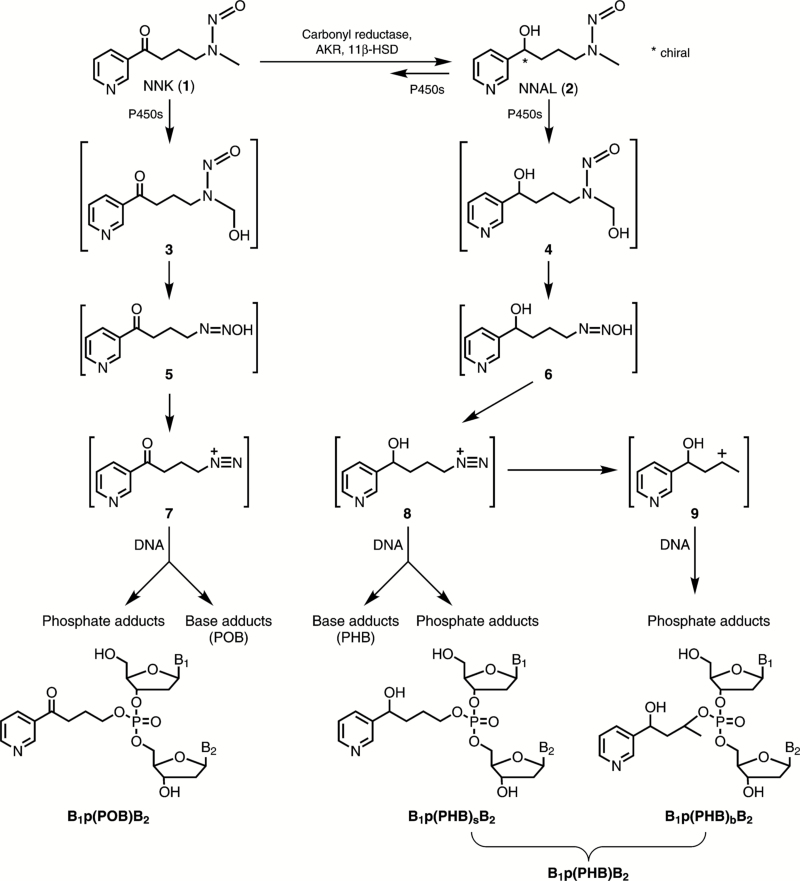

Figure 1.

Pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA adduct formation by NNAL and NNK. B1 and B2 represent the same or different nucleobases.

Metabolic activation of NNK by α-hydroxylation results in the formation of reactive intermediate 3. The intermediate 3 can decompose to 5 and then to a diazonium ion 7, which reacts with DNA to form DNA adducts. The intermediate 7 reacts with nucleobases to form pyridyloxobutyl (POB) base adducts (6), and also reacts with the oxygen of the phosphodiester linkages in DNA to form pyridyloxobutyl phosphate adducts, or B1p(POB)B2 adducts, where B1 and B2 represent the same or different nucleobases (Figure 1) (7). The major POB base adducts and B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts have been characterised, and their levels have been quantified in animals treated with NNK (4,6–8). Like NNK, metabolic activation of NNAL by α-hydroxylation produces an intermediate 4, which similarly decomposes to a diazonium ion 8. The diazonium ion 8 reacts with DNA nucleobases to form pyridylhydroxybutyl (PHB) base adducts (8,9). In a separate study, we demonstrated that 8 also reacted with the oxygen of the phosphodiester linkages in DNA to form pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts B1p(PHB)sB2 (Figure 1), where the subscript s represents ‘straight chain’ in DNA (10). The intermediate 8 also rearranged to a secondary carbocation 9 (11), which reacted with DNA to form B1p(PHB)bB2 (Figure 1), where the subscript b represents ‘branched chain’ (10). The B1p(PHB)sB2 and B1p(PHB)bB2 phosphate adducts are collectively named as B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts to indicate that both types of adducts are produced from NNAL.

NNAL has a chiral centre at the carbinol carbon and thus exists in the enantiomeric forms (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL. In a previous study, we reported the carcinogenicity of 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL or (S)-NNAL administered in the drinking water to male F-344 rats for up to 70 weeks. Both enantiomers selectively induced a high incidence of lung tumours (4). The analysis of DNA adduct formation in the NNAL-treated rats could provide critical information to relate DNA damage to the carcinogenicity of these compounds. Therefore, in this study, we describe the detection and quantitation of pulmonary B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 adducts in rats treated with (R)-NNAL or (S)-NNAL in their drinking water for 10, 30, 50 and 70 weeks. The contributions of different types of phosphate and base adducts to the total measured DNA adducts were also investigated. This study presents important new data on DNA damage caused by NNAL enantiomers, and identifies DNA phosphate adducts as potential biomarkers for mechanistic investigation of tobacco exposure-induced carcinogenesis.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Two diastereomers of dCp[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]dC [Cp(POB)C-1 and Cp(POB)C-2], and two diastereomers of Tp[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]T [Tp(POB)T-1 and Tp(POB)T-2] were purchased from WuXi AppTec (Hong Kong). [15N3]Cp(POB)C was synthesised in our previous study (7). The other standards, including dCp[4-hydroxy-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]dC [Cp(PHB)sC], Tp[4-hydroxy-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]T [Tp(PHB)sT], [15N3]Cp(PHB)sC and [13C1015N2]Tp(PHB)sT, were prepared as described (10). Enzymes and reagents for DNA isolation were purchased from Qiagen Sciences (Germantown, MD, USA). All other chemicals and solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI, USA).

In vivo DNA samples

The in vivo DNA samples were from lung tissues of male F-344 rats (n = 3) treated chronically with 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL or (S)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 and 70 weeks (4). DNA was isolated using our previously developed protocol (6), and stored at −20°C until analysis.

DNA hydrolysis and sample preparation

The DNA samples (~200 μg) were dissolved in 0.6 ml of 10 mM sodium succinate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5 mM CaCl2. A mixture of internal standards containing 10 fmol [15N3]Cp(POB)C, [13C1015N2]Tp(POB)T, [15N3]Cp(PHB)sC and [13C1015N2]Tp(PHB)sT was added to the solution. The DNA solution was then mixed with deoxyribonuclease I (60 units), phosphodiesterase I (0.03 units), and alkaline phosphatase (40 units), and incubated overnight at 37°C. On the next day, 20 μl of hydrolysate was collected for dGuo analysis and DNA quantitation (6). The remaining hydrolysate was processed by filtration through 10 K centrifugal filters (Ultracel YM-10, Millipore), and purified by 30-mg Strata X cartridges (Phenomenex) activated with 2 ml of MeOH and 2 ml of H2O. The cartridges were washed with 2 ml of H2O and 1 ml of 10% MeOH sequentially and finally eluted with 2 ml of 50% MeOH. The 50% MeOH fraction containing analytes was concentrated to dryness in a centrifugal evaporator. The residue was redissolved in 10 μl of deionised H2O and analysed by mass spectrometry.

LC-NSI-HRMS/MS analysis

The analysis was conducted using a liquid chromatography (LC)-nanoelectrospray ionisation (NSI)-high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (HRMS/MS) method. Briefly, the analysis was performed on an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using full scan, selected-ion monitoring (SIM) and product ion scan modes. A nanoLC column (75 μm i.d., 360 μm o.d., 20 cm length and 15 μm orifice) packed with Luna C18 bonded separation media (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used. The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM NH4OAc and CH3CN. All samples were analysed twice to measure B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 adducts separately. The chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions for analysis of B1p(POB)B2 have been described (7). The chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions for analysis of B1p(PHB)B2 were similar to those of B1p(POB)B2 except that the m/z of precursor ions of B1p(PHB)B2 was two mass units higher than the corresponding B1p(POB)B2. Also, the product ion scan was performed using higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation with a normalised collision energy of 25 units [B1p(PHB)B2] instead of 20 units [B1p(POB)B2] in this assay.

For Cp(POB)C, Tp(POB)T, Cp(PHB)sC and T(PHB)sT, quantitation was based on the peak area ratio of each adduct to their corresponding isotope-labelled internal standards, the constructed calibration curves, and the amount of internal standards added. For those adducts for which standards were not available, a semi-quantitative approach was applied to estimate the levels of all the other phosphate adducts based on their MS signal intensities compared to Cp(POB)C or Tp(POB)T [for B1p(POB)B2], and Cp(PHB)sC or Tp(PHB)sT [for B1p(PHB)B2] under the SIM scan mode. The average signal response of the Cp(POB)C and Tp(POB)T [for B1p(POB)B2], and Cp(PHB)sC and Tp(PHB)sT [for B1p(PHB)B2] calibration curves was used to estimate the levels of the other phosphate adducts. At the same molar amount, the MS signal intensities of Tp(POB)T and Tp(PHB)sT were five and two times higher than Cp(POB)C and Cp(PHB) sC, respectively. This observation suggests that different base combinations of the DNA phosphate adducts may have different ionisation efficiencies under the current conditions. Thus, the levels of adducts without standards were based on these semi-quantitation methods mentioned above.

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of adduct levels between the (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL treatment groups were performed using the two-tailed unpaired t-test. Comparison of adduct levels at different time points were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Because B1 and B2 represent the same or different nucleobases, there can be 10 different combinations of B1p(PHB)B2 or B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts. With B1 and B2 being different bases, there can be two different types of isomers: B1-3′-p-5′-B2 and B1-5′-p-3′-B2. In this study, we use B1pB2 to represent both types [e.g. Ap(PHB)T represents both A-3′-p(PHB)-5′-T and A-5′-p(PHB)-3′-T]. There can be 32 different isomers of B1p(POB)B2 adducts due to the chiral centre in the phosphate group (Table 1) (7). Both (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL are re-oxidised by rat lung microsomes to NNK (12), which is then converted back to partially racemised NNAL. Thus, there can be 64 different isomers of B1p(PHB)sB2 adducts due to another chiral centre at the hydroxyl group in the structure. An additional chiral centre is introduced on the methyl-bearing carbon of B1p(PHB)bB2 adducts, which can lead to formation of 128 different isomers. Therefore, there can be a total of 192 different isomers of B1p(PHB)B2 adducts (Table 1). Both B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 adducts were analysed in the lung tissues of rats treated with (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL.

Table 1.

DNA phosphate adducts detected in lung of rats treated with (R)- and (S)-NNAL

| Combination | Number of isomers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible | Detected | ||||||||

| B1p(POB)B2 | B1p(PHB)B2 | Total | (R)-NNAL | (S)-NNAL | |||||

| B1p(POB)B2 | B1p(PHB)B2 | Total | B1p(POB)B2 | B1p(PHB)B2 | Total | ||||

| A-A | 2 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| C-C | 2 | 12 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| G-G | 2 | 12 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| T-T | 2 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| A-C | 4 | 24 | 28 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| A-G | 4 | 24 | 28 | 2 | 11 | 13 | 3 | 11 | 14 |

| A-T | 4 | 24 | 28 | 2 | 17 | 19 | 4 | 15 | 19 |

| C-G | 4 | 24 | 28 | 1 | 18 | 19 | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| C-T | 4 | 24 | 28 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| G-T | 4 | 24 | 28 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Total | 32 | 192 | 224 | 19 | 95 | 114 | 28 | 92 | 120 |

DNA phosphate adduct formation in (R)-NNAL- treated rats

Utilising the standards of Cp(PHB)sC (Figure 2A), the identities of Cp(PHB)sC and Cp(PHB)bC were confirmed during the analysis, and a typical chromatogram of these adducts in the lung DNA from a rat treated with (R)-NNAL for 50 weeks is presented in Figure 2B. Under the current chromatographic conditions, the two isomers of Cp(PHB)sC eluted earlier, followed by the four isomers of Cp(PHB)bC. Like Cp(PHB)C, the identities of the two types of Tp(PHB)T adducts [i.e. Tp(PHB)sT and Tp(PHB)bT] were confirmed by standards (Figure 2C and D). A typical chromatogram obtained upon analysis of Tp(PHB)T in the lung DNA from a rat treated with (R)-NNAL for 50 weeks is presented in Figure 2D. Tp(PHB)sT eluted earlier, followed by the four isomers of Tp(PHB)bT. The levels of Cp(PHB)sC decreased after 30 weeks, while the levels of Cp(PHB)bC increased over time, reached a peak at 50 weeks, and persisted afterwards (Figure 3A). Therefore, the increase and persistence of Cp(PHB)bC contributed to the overall increase of Cp(PHB)C levels over the course of the study. Similar to the isomers of Cp(PHB)C, the levels of Tp(PHB)sT decreased after 30 weeks, while the levels of Tp(PHB)bT increased over time (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Typical chromatograms obtained upon analysis of (A) Cp(PHB)sC and [15N3]Cp(PHB)sC standards, (B) Cp(PHB)C in a lung DNA sample from a rat treated with (R)-NNAL for 50 weeks, (C) Tp(PHB)sT and [13N1015N2]Tp(PHB)sT standards, and (D) Tp(PHB)T in a lung DNA sample from a rat treated with (R)-NNAL for 50 weeks.

Figure 3.

Levels of (A) Cp(PHB)C and (B) Tp(PHB)T in lung tissues of rats (n = 3) treated with 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 or 70 weeks; Levels of (C) Cp(PHB)C and (D) Tp(PHB)T in lung tissues of rats (n = 3) treated with 5 ppm of (S)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 or 70 weeks. Values are presented as means ± SD.

The identities of the other B1p(PHB)B2 adducts without standards were based on the accurate masses of the precursor ions and the corresponding fragment ions. With Ap(PHB)T as an example, its extracted ion chromatograms upon analysis of lung DNA from a rat treated with (R)-NNAL for 50 weeks, and the proposed fragmentation pattern of Ap(PHB)C are presented in Figure 4. Using the same strategy, at least five isomers of B1p(PHB)B2 and at least one isomer of B1p(POB)B2 for each set of base combinations were detected. A total of 95 out of 192 possible B1p(PHB)B2 adducts and 19 out of 32 possible B1p(POB)B2 adducts were chromatographically separable and detected in the lung tissue under these conditions (Table 1). Three major B1p(PHB)B2 adducts were observed, namely Cp(PHB)T, Ap(PHB)C, and Ap(PHB)T, which accounted for 18–20%, 15–16%, and 15–16% of the total B1p(PHB)B2 adducts, respectively (Figure 5A). For most of the B1p(PHB)B2 adducts, the levels increased from 10 weeks-treatment to 30 weeks-treatment, and stayed persistent throughout the rest of the study. For example, the levels of Cp(PHB)T increased from 823 ± 93 fmol/mg DNA at 10 weeks of treatment to 1290 ± 107 fmol/mg DNA at 30 weeks of treatment (P < 0.05), and were not significantly changed afterwards with levels of 1270 ± 64 and 1350 ± 91 fmol/mg DNA at 50 and 70 weeks, respectively. The B1p(POB)B2 adducts were formed to a much lesser extent, ranging from 46 to 175 fmol/mg DNA over the course of the study (Figure 5B), compared to 4530–6920 fmol/mg DNA of B1p(PHB)B2 adducts. Some base combinations, e.g. Tp(POB)T and Cp(POB)T, were not detected in the lung DNA of rats from 70 weeks of treatment (Figure 5B).

Figure 4.

Typical chromatograms of the extracted precursor (m/z 705.2392, SIM) and major fragment ions, and a proposed fragmentation pattern of Ap(PHB)T obtained upon analysis of lung DNA of a rat treated with (R)-NNAL in drinking water (5 ppm) for 50 weeks.

Figure 5.

Levels of (A) pyridylhydroxybutyl and (B) pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts in lung tissues of rats (n = 3) treated with 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL, and levels of (C) pyridylhydroxybutyl and (D) pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts in lung tissues of rats (n = 3) treated with 5 ppm of (S)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 or 70 weeks. Values are presented as means ± SD.

DNA phosphate adduct formation in (S)-NNAL- treated rats

Compared to the (R)-NNAL treatment group, similar formation patterns of B1p(PHB)sB2 and B1p(PHB)bB2 isomers were observed for the C-C and T-T combinations in the (S)-NNAL treatment group (Figure 3C and D). At least five isomers and two isomers of each combination were detected for B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 adducts, respectively. A total of 92 out of 192 possible B1p(PHB)B2 adducts and 28 out of 32 possible B1p(POB)B2 adducts were detected in the lung tissue (Table 1). Similar to the (R)-NNAL treatment group, the three most abundant adducts were Cp(PHB)T, Ap(PHB)C, and Ap(PHB)T, which accounted for 19–23%, 11–16%, and 18–21% of the total B1p(PHB)B2 adducts, respectively (Figure 5C). For most of the B1p(PHB)B2 adducts, once formed, their levels were not significantly changed over the course of the study. Different from the B1p(PHB)B2 adducts, the levels of B1p(POB)B2 adducts were maximal at 10 weeks, and decreased afterwards (Figure 5D). For example, the level of Cp(POB)T decreased from 853 ± 93 fmol/mg DNA at 10 weeks of treatment to 232 ± 61 fmol/mg DNA at 70 weeks of treatment (P < 0.05). While the B1p(PHB)B2 adduct levels between the (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL treatment groups were only 1.2–1.8-fold different [higher in the (R)-NNAL group, P < 0.05], the difference of B1p(POB)B2 adduct levels between the two groups was more drastic, with the levels in the (S)-NNAL group 8–34 times higher than the (R)-NNAL group (P < 0.01).

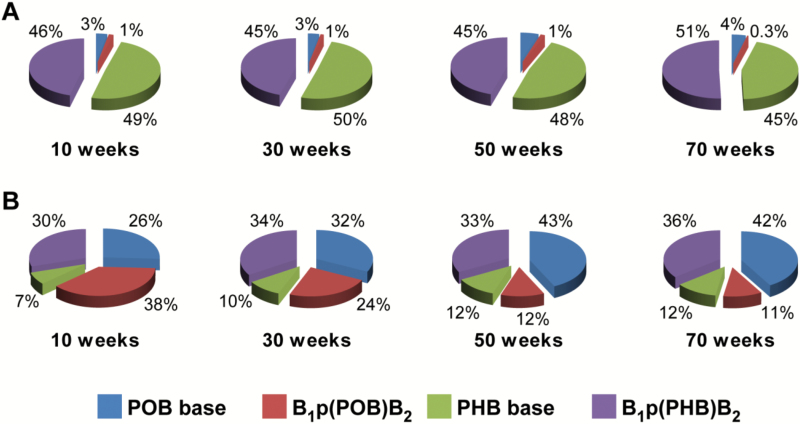

Comparison of DNA phosphate and base adducts formed by NNAL

In addition to B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts, the levels of their corresponding base adducts (PHB and POB base adducts) were obtained from our previous studies (4), to determine the relative proportion of each type of adduct to the total identified pyridine-containing DNA adducts formed in rats treated with NNAL (Table 2). In rat lung, the levels of two major PHB base adducts—O2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-hydroxybut-1-yl]thymidine and 7-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-hydroxybut-1-yl]guanine—and three major POB base adducts—O2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]thymidine, 7-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]guanine and O6-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl]deoxyguanosine—were reported pre-vi ously (4). In the (R)-NNAL treatment group, B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts and PHB base adducts were by far the most abundant types of adducts, accounting for 45–51% and 45–50% of the total measured DNA adducts, respectively (Figure 6A). In the (S)-NNAL treatment group, B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts were the most abundant type in the 10 weeks treatment group (38%), but decreased afterwards (24%, 12%, and 11% in 30, 50, and 70 weeks-treatment groups, respectively). The levels of B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts and POB base adducts were comparable over the course of the study, accounting for 30–36% and 26–43%, respectively, of the total measured DNA adducts, followed by PHB base adducts (7–12%) (Figure 6B). The total amount of measured DNA phosphate and base adducts were calculated and compared between (R)-NNAL- and (S)-NNAL-treated rats (Table 2). The levels of total adducts in (R)-NNAL-treated rats were lower at 10 weeks, but higher at 30 and 50 weeks than those in (S)-NNAL-treated rats (P < 0.05), while their levels were comparable at 70 weeks (Table 2).

Table 2.

Levels of total B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts, total B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts, total POB base adducts, and total PHB base adducts in lung tissue of rats treated with 5 ppm of (R)-NNAL, (S)-NNAL and NNK in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 or 70 weeks

| Treatment | Adduct | Level (fmol/mg DNA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 weeks | 30 weeks | 50 weeks | 70 weeks | ||

| (R)-NNAL | B1p(PHB)B2 | 4530 ± 368 | 6670 ± 211 | 6280 ± 336 | 6920 ± 436 |

| B1p(POB)B2 | 136 ± 32 | 135 ± 30 | 175 ± 17 | 46d | |

| PHB basea | 4880 ± 721 | 7440 ± 507 | 6670 ± 885 | 6170 ± 1770 | |

| POB basea | 323 ± 36 | 490 ± 81 | 720 ± 46 | 545 ± 112 | |

| Total | 9870 ± 811 | 14700 ± 556 | 13800 ± 948 | 13700 ± 1820 | |

| (S)-NNAL | B1p(PHB)B2 | 3670 ± 67 | 4180 ± 119 | 3480 ± 79 | 3820 ± 582 |

| B1p(POB)B2 | 4650 ± 356 | 2910 ± 109 | 1310 ± 77 | 1180 ± 204 | |

| PHB basea | 847 ± 34 | 1210 ± 30 | 1250 ± 48 | 1270 ± 311 | |

| POB basea | 3180 ± 664 | 3950 ± 371 | 4530 ± 335 | 4470 ± 265 | |

| Total | 12400 ± 757 | 12200 ± 406 | 10600 ± 356 | 10700 ± 740 | |

| NNK | B1p(PHB)B2b | 6390 ± 457 | 8160 ± 654 | 4000 ± 291 | 3950 ± 223 |

| B1p(POB)B2c | 475 ± 95 | 417 ± 43 | 346 ± 41 | 218 ± 15 | |

| PHB basea | 1200 ± 49 | 1530 ± 104 | 1390 ± 74 | 869 ± 143 | |

| POB basea | 4600 ± 440 | 5570 ± 195 | 5110 ± 327 | 2300 ± 473 | |

| Total | 12600 ± 643 | 15700 ± 692 | 10800 ± 446 | 7340 ± 542 | |

Values are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 or 5).

aThe data of POB and PHB base adduct levels in rat lung are from Balbo, S., et al. (2014) Carcinogenesis, 35, 2798–2806.

bThe data of total B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adduct levels are from (10).

cThe data of total B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adduct levels are from Ma, B., et al. (2015) Chem. Res. Toxicol., 28, 2151–2159.

dSingle measurement.

Figure 6.

Relative levels of DNA phosphate and base adducts in lung DNA of rats treated with 5 ppm of (A) (R)-NNAL and (B) (S)-NNAL in drinking water for 10, 30, 50 or 70 weeks.

Discussion

In this study, we measured the formation of pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts in the lung of rats treated chronically with (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL in a carcinogenicity study. The pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts [B1p(PHB)B2] were formed directly by metabolic activation of NNAL, while the pyridyloxobutyl phosphate adducts [B1p(POB)B2] were formed via NNAL conversion to NNK and subsequent bioactivation of NNK (12). Both types of phosphate adducts were detected and quantified in the two treatment groups. Like DNA base adducts in our previous studies (4,8,9), distinct patterns of phosphate adduct formation were observed in the (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL treatment groups. The differences in DNA adduct formation are likely due to differences in metabolism of (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL in rats.

In rat lung microsomes, the metabolism of (S)-NNAL is significantly faster than that of (R)-NNAL, notably for the formation of α-methyl hydroxylation-derived 1-(3-pyridyl)-1,4-butanediol, the product of intermediate 8 reacting with H2O (12). Pyridine-N-oxidation and re-oxidation to NNK are also significantly faster with (S)-NNAL as a substrate compared to (R)-NNAL (12,13). With different metabolic rates of the two enantiomers in rat lung, it is reasonable to expect different formation patterns of DNA adducts, and in previous studies we have observed that PHB base adducts are the major type of adduct formed from (R)-NNAL while (S)-NNAL and NNK behave similarly and produce mainly POB base adducts (9). This trend was also observed in the present study. The levels of B1p(PHB)B2 adducts (NNAL-derived) in the (R)-NNAL-treated rats were 1.2–1.8 times higher (P < 0.05) than in the (S)-NNAL-treated rats. The levels of B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts and POB base adducts (both NNK-derived) in the (S)-NNAL-treated rats were 7–34 times (P < 0.0001) and 6–10 times (P < 0.001) higher, respectively, than in the (R)-NNAL-treated rats. The different conversion rates from the two enantiomers of NNAL to NNK also resulted in different contributions of each type of adduct to the total amount of measured adducts. In the (R)-NNAL-treated rats, the NNAL-derived adducts [B1p(PHB)B2 + PHB base] were predominant, consisting of 94–96% of the total adducts, while the NNK-derived adducts [B1p(POB)B2 + POB base] were more abundant in the (S)-NNAL-treated rats, consisting of 53–63% of the total adducts.

As noted above, our previous studies demonstrated that (S)-NNAL behaves similarly as NNK in many respects, while (R)-NNAL was significantly different (4,8,9). This finding also applies to the DNA base adduct formation by these compounds. In rat lung, the levels of total PHB base adducts were similar between (S)-NNAL and NNK groups (P > 0.05), compared to significantly higher levels in the (R)-NNAL group (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Similarly, the levels of total POB base adducts between the NNK and (S)-NNAL groups were only 0.5–1.4-fold [NNK/(S)-NNAL] different, compared to 4-14-fold [NNK/(R)-NNAL, P < 0.01] difference between the NNK and (R)-NNAL groups (4). At 50 and 70 weeks of treatment, the formation pattern of B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts in the lung tissues of rats treated with (S)-NNAL mirrored those treated with NNK (P > 0.05), while the levels were significantly higher in the (R)-NNAL group (P < 0.001, Table 2). However, at 10 and 30 weeks of treatment, the levels of B1p(PHB)B2 phosphate adducts in NNK-treated rats were the highest, followed by the (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL groups. The similarity of (S)-NNAL and NNK was not observed in B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adduct formation. Significantly higher (P < 0.001) levels of B1p(POB)B2 adducts were formed in the (S)-NNAL group than in the NNK group. Previous studies demonstrated that (S)-NNAL is retained in the tissues of rats, specifically the lung (13,14), which could contribute to the formation of more B1p(POB)B2 adducts in the (S)-NNAL group.

The persistence of DNA phosphate adducts in vivo has been demonstrated in previous studies. For example, methyl and ethyl DNA phosphate adducts were more persistent than their corresponding base adducts in animals treated with alkylating agents (15–18). Our studies also demonstrated that certain B1p(PHB)B2 and B1p(POB)B2 phosphate adducts were persistent in rats treated with NNK over the 70 weeks of treatment (7,10). Consistent with these previous findings, some of the phosphate adducts in the current study were also persistent over the 70 weeks of treatment in rats treated with (R)-NNAL and (S)-NNAL. Compared to the decrease over time of most base adducts, the persistence of Cp(PHB)bC and Tp(PHB)bT in the lung over time and the increase of Tp(PHB)bT in the lung of (R)-NNAL-treated rats (Figure 3) are particularly notable. CYP2A6 and CYP2A13, which catalyse α-hydroxylation of NNAL and NNK, were detected in human lung microsomes (19–21), suggesting this metabolic pathway may also occur in smokers who are exposed to NNAL and NNK. Thus, the persistent DNA phosphate adducts such as Cp(PHB)bC and Tp(PHB)bT might be detected in people chronically exposed to tobacco products, suggesting their potential value as biomarkers of tobacco-associated carcinogenesis.

With such persistence in vivo, these NNAL/NNK-derived phosphate adducts may be biologically significant. Previous studies on other phosphate adducts have demonstrated the impacts of phosphate group modifications on DNA binding affinity and metabolic enzymes and helicases (22–26). However, the consequences of these pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts are still unclear and warrant further study. With the outcomes of future studies on biological relevance of these DNA phosphate adducts, we may have a better understanding of the role of these adducts in NNAL- and NNK-related carcinogenesis. This study focused on measurement of pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts, which are specific to NNAL and NNK. Methyl-DNA base adducts were also detected in NNAL-treated rats (3,4), and the possible formation and characterisation of methyl-phosphate adducts in NNAL- and NNK-treated rats will be reported separately.

In summary, we quantified pyridylhydroxybutyl and pyridyloxobutyl DNA phosphate adducts formed in rats exposed to individual enantiomers of NNAL, metabolites of the tobacco-specific carcinogen NNK. Our findings demonstrate that pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts are one of the most abundant types of all identified adducts in rat lung. Some of the pyridylhydroxybutyl phosphate adducts [e.g. Tp(PHB)bT] persisted during 70 weeks of chronic treatment with individual enantiomers of NNAL. The results of this study suggest that these NNAL/NNK-derived phosphate adducts could be potential biomarkers of chronic exposure to NNAL and NNK, and could be used in future studies of tobacco carcinogenesis.

Funding

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (CA-81301). Mass spectrometry was carried out in the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, supported in part by National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (CA-77598). Salary support for P.W.V. was provided by National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (CA-211256).

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xun Ming for his help with the mass spectrometry analysis, and Robert Carlson for editorial assistance.

References

- 1. International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2007)Smokeless Tobacco and Tobacco-specific Nitrosamines. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 89 International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hecht S. S. (1998)Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 11, 559–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hecht S. S. Stepanov I. and Carmella S. G (2016)Exposure and metabolic activation biomarkers of carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Acc. Chem. Res., 49, 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balbo S., Johnson C. S., Kovi R. C., et al. (2014)Carcinogenicity and DNA adduct formation of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of its metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol in F-344 rats. Carcinogenesis, 35, 2798–2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peterson L. A. (2017)Context matters: contribution of specific DNA adducts to the genotoxic properties of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 30, 420–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lao Y. Villalta P. W. Sturla S. J. Wang M. and Hecht S. S (2006)Quantitation of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in rat tissue DNA by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 19, 674–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma B. Villalta P. W. Zarth A. T. Kotandeniya D. Upadhyaya P. Stepanov I. and Hecht S. S (2015)Comprehensive high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis of DNA phosphate adducts formed by the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 28, 2151–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang S. Wang M. Villalta P. W. Lindgren B. R. Upadhyaya P. Lao Y. and Hecht S. S (2009)Analysis of pyridyloxobutyl and pyridylhydroxybutyl DNA adducts in extrahepatic tissues of F344 rats treated chronically with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 22, 926–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Upadhyaya P. Kalscheuer S. Hochalter J. B. Villalta P. W. and Hecht S. S (2008)Quantitation of pyridylhydroxybutyl-DNA adducts in liver and lung of F-344 rats treated with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of its metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 21, 1468–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma B. Zarth A. T. Carlson E. S., Villalta P. W. Upadhyaya P. Stepanov I. and Hecht S. S (2017)Identification of more than one hundred structurally unique DNA-phosphate adducts formed during rat lung carcinogenesis by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Carcinogenesis, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spratt T. E. Peterson L. A. Confer W. L. and Hecht S. S (1990)Solvolysis of model compounds for alpha-hydroxylation of N’-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone: evidence for a cyclic oxonium ion intermediate in the alkylation of nucleophiles. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 3, 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Upadhyaya P. Carmella S. G. Guengerich F. P. and Hecht S. S (2000)Formation and metabolism of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol enantiomers in vitro in mouse, rat and human tissues. Carcinogenesis, 21, 1233–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimmerman C. L. Wu Z. Upadhyaya P. and Hecht S. S (2004)Stereoselective metabolism and tissue retention in rats of the individual enantiomers of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), metabolites of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK). Carcinogenesis, 25, 1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu Z. Upadhyaya P. Carmella S. G. Hecht S. S. and Zimmerman C. L (2002)Disposition of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in bile duct-cannulated rats: stereoselective metabolism and tissue distribution. Carcinogenesis, 23, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones G. D. Le Pla R. C. and Farmer P. B (2010)Phosphotriester adducts (PTEs): DNA’s overlooked lesion. Mutagenesis, 25, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singer B. (1985)In vivo formation and persistence of modified nucleosides resulting from alkylating agents. Environ. Health Perspect., 62, 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Den Engelse L. De Graaf A. De Brij R. J. and Menkveld G. J (1987)O2- and O4-ethylthymine and the ethylphosphotriester dTp(Et)dT are highly persistent DNA modifications in slowly dividing tissues of the ethylnitrosourea-treated rat. Carcinogenesis, 8, 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shooter K. V. and Slade T. A (1977)The stability of methyl and ethyl phosphotriesters in DNA in vivo. Chem. Biol. Interact., 19, 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang X. D’Agostino J. Wu H. Zhang Q. Y. von Weymarn L. Murphy S. E. and Ding X (2007)CYP2A13: variable expression and role in human lung microsomal metabolic activation of the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 323, 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown P. J. Bedard L. L. Reid K. R. Petsikas D. and Massey T. E (2007)Analysis of CYP2A contributions to metabolism of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in human peripheral lung microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos., 35, 2086–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith G. B. Bend J. R. Bedard L. L. Reid K. R. Petsikas D. and Massey T. E (2003)Biotransformation of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in peripheral human lung microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos., 31, 1134–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eoff R. L. Spurling T. L. and Raney K. D (2005)Chemically modified DNA substrates implicate the importance of electrostatic interactions for DNA unwinding by Dda helicase. Biochemistry, 44, 666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suhasini A. N. Sommers J. A. Yu S. Wu Y. Xu T. Kelman Z. Kaplan D. L. and Brosh R. M. Jr (2012)DNA repair and replication fork helicases are differentially affected by alkyl phosphotriester lesion. J. Biol. Chem., 287, 19188–19198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan I. Sommers J. A. and Brosh R. M. Jr (2015)Close encounters for the first time: helicase interactions with DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst)., 33, 43–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Makishi S. Shibata T. Okazaki M. Dohno C. and Nakatani K (2014)Modulation of binding properties of amphiphilic DNA containing multiple dodecyl phosphotriester linkages to lipid bilayer membrane. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 24, 3578–3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yashiki T., Yamana K., Nunota K. and Negishi K (1992)Sequence specific block of in vitro DNA synthesis with isopropyl phosphotriesters in template oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 27, 197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]