Abstract

Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) is understood to be the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD), and is also a frequent co-morbidity with AD. While VCID is widely acknowledged as a key contributor to dementia, the mechanistic underpinnings of VCID remain poorly understood. In this review, we address the potential role of astrocytes in the pathophysiology of VCID. The vast majority of the blood vessels in the brain are surrounded by astrocytic end-feet. Given that astrocytes make up a significant proportion of the cells in the brain, and that astrocytes are usually passively connected to one-another through gap junctions, we hypothesize that astrocytes are key mediators of cognitive impairment due to cerebrovascular disease. In this review, we discuss the existing body of literature regarding the role of astrocytes at the vasculature in the brain, and the known consequences of their dysfunction, as well as our hypotheses regarding the role astrocytes play in VCID.

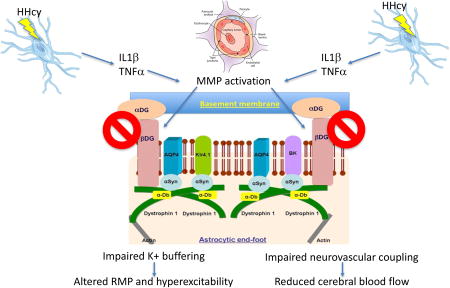

Graphical abstract

We propose that hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) results in a pro-inflammatory response at the vasculature, which activates the matrix metalloproteinase MMP9. MMP9 subsequently cleaves the a-b dystroglycan complex, leading to disruption of the astrocytic connection with the vasculature. MMP9 also degrades the dystrophin Dp71 anchoring complex, resulting in the downregulation of astrocytic end-foot channels. The end-result of the end-foot disruption is impaired potassium homeostasis in the brain and impaired neurovascular coupling.

VCID

Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) are acknowledged to be the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD), with up to 30% of dementia cases ascribed to VCID (Levine & Langa 2011). VCID is commonly observed as a co-morbidity with other common dementias including AD, with estimates of approximately 60% of AD patients showing significant VCID (Bowler et al. 1998, Kammoun et al. 2000, Langa et al. 2004). Dementia symptoms such as confusion, disorientation and trouble understanding speech can occur following a major stroke, making stroke the most obvious, acute cause of VCID. However, the majority of VCID cases, in particular those composing AD co-morbidities, are those that have a more-subtle pathophysiologies such as microinfarcts (microscopic ischemic events), chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, cerebrovascular occlusions and cerebral microhemorrhages (Levine & Langa 2011). Important risk factors for VCID include lacunar and larger cerebral infarct in the brain that are pathological markers of clinical or subclinical stroke (Snyder et al. 2015). Pathologies such as macro- and microinfarcts and vessel disease (e.g. atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)) often produce ischemic brain injury. These pathologies are commonly detected in the aging brain and have been shown to be independent risk factors for cognitive impairment and dementia (Jiwa et al. 2010).

There remains debate in the dementia field as to whether AD and VCID processes synergize or are simply independent, additive processes. Supporting synergistic effects of the pathologies, VCID and AD share some molecular mechanisms including neuroinflammation and brain metabolic changes. One such area of common mechanisms surrounds clearance pathways of beta-amyloid (Aβ). In brains of individuals with AD, a decrease in blood flow has been observed prior to Aβ deposition. This suggests changes in the cerebrovasculature impairs clearance of Aβ, accelerating the progression of AD (Snyder et al. 2015).

The innate immune system represents a potential area of overlap between AD and vascular disease is the innate immune system. Chronic inflammation around plaques and tangles is frequently found in both human and mouse AD neuropathological studies. Genomic wide association studies (GWAS) suggest microglia and infiltrating monocytes may drive AD pathogenesis. Blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption is commonly found in post-mortem brain tissue suggesting an intersection point to immune infiltration and VCID (Arvanitakis et al. 2011, Smith et al. 2012). In this review, we will focus on the potential role of the neurovascular astrocyte in VCID pathophysiology.

Neurovascular unit

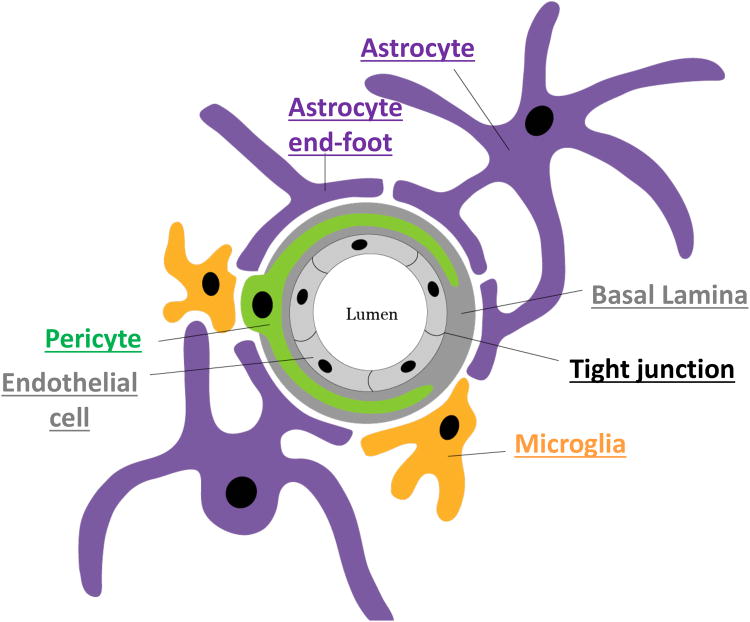

The neurovascular unit is comprised primarily of vascular endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes and neurons (Figure 1). However, in recent years, the cellular anatomy has been extended to include both microglia and perivascular macrophages (Keaney & Campbell 2015). The neurovascular unit functions to regulate local cerebral blood flow (CBF), BBB permeability, neuroimmune responses and neurovascular remodeling (Kapasi & Schneider 2016, Stanimirovic & Friedman 2012). Endothelial cells of the neurovascular unit line the cerebral vasculature forming the BBB. Tight junctions of the BBB express specific transporters and thereby limit the passage of substrates between cells (Keaney & Campbell 2015). Pericytes have elongated processes that ensheath CNS vessel walls and serve important roles in regulating capillary diameter, cerebral blood flow and extracellular matrix protein secretion (Keaney & Campbell 2015, Winkler et al. 2011). Finally, astrocytes aid in supporting and protecting neurons by maintaining homeostatic concentrations of specific ions and neurotransmitters and also regulate CBF by directly interacting with endothelial cells through their specialized end-feet processes (Keaney & Campbell 2015). The role the individual cell types play in the regulation of blood flow and brain metabolism has been thoroughly reviewed by others. This review specifically focuses on the astrocytes, and their potential role in the pathophysiology of VCID.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing arrangement of the cells of the neurovascular unit.

Neurovascular astrocytes

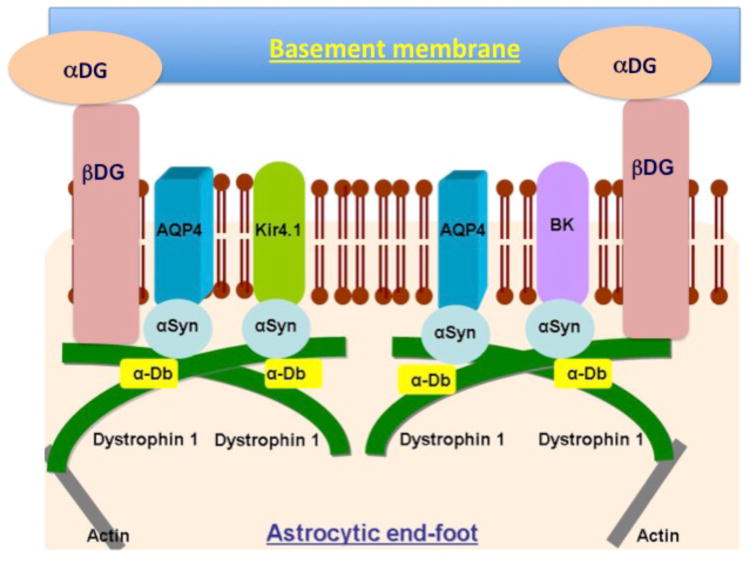

Astrocytes play several key roles in maintaining the health of the neurons. In addition to their recognized role in maintaining synapses through regulation of glutamate, astrocytes also have a key role in maintenance of ionic and osmotic homeostasis in the brain (Simard & Nedergaard 2004). The cerebrovasculature of the brain, primarily arterioles and capillaries, are almost completely ensheathed by astrocytic processes called astrocytic end-feet. The astrocytic end-foot is a specialized unit that functions to maintain the ionic and osmotic homeostasis of the brain (Amiry-Moghaddam et al. 2003, Simard & Nedergaard 2004). Astrocytic end-feet express a number of channels indicative of their specialized functions. End-feet enriched channels include the aquaporin 4 (AQP4) water channel, the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1, and the Ca2+-dependent K+ channel MaxiK (Dunn & Nelson 2010, Strohschein et al. 2011). The astrocytic end-foot is anchored to the vascular basement membranes via the α-β dystroglycan complex (Noell et al. 2011, Gondo et al. 2014) (schematic shown in figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic showing channel arrangement at the astrocytic end-foot. Abbreviations in the figure are: αDG: alpha-dystroglycan; βDG: beta-dystroglycan; AQP4: aquaporin 4; Kir4.1: Inwardly-rectifying K+ channel 4.1; BK: Ca2+-dependent K+ channel; α-DB: alpha-dystrobrevin; α-Syn: alpha-syntrophin; Dystrophin 1; Dp71 short form of dystrophin 1 protein.

Potassium buffering

Neurons maintain a resting membrane potential (rmp) of approximately -60 to -70mV. A classic experiment by Hodgkin and Katz in 1949 using the squid giant axon demonstrated that this rmp is determined by the K+ concentration gradient across the membrane (high intracellular K+, low extracellular K+). They showed that increasing the extracellular K+ concentration results in the rmp being less negative (Hodgkin & Katz 1949). When an action potential is initiated the membrane depolarizes and Na+ and K+ enter the neuron. The neuron must reach a threshold in order to fire an action potential. This threshold varies among different neurons but is approximately -40 to -50mV. After the peak membrane potential of approximately +60mV is reached the membrane repolarizes by inactivation of Na+ channels and an increase in K+ permeability. There is a brief hyperpolarization (undershoot) where the K+ permeability is even greater than at rest. This also prevents another rapid depolarization (termed the refractory period) (Ritchie & Straub 1975). The efflux of K+ ions during action potential firing must be removed in order for the membrane to adequately repolarize and reset channel function for the next electrical signal to occur (Kofuji & Newman 2004).

An essential function of the astrocytes surrounding the neurons is to maintain the neuronal rmp by controlling the extracellular potassium concentration, a process termed potassium siphoning (Newman et al. 1984). It has been shown that through Kir4.1 channels (Neusch et al. 2006) and the connexin 43- containing gap junctions the astrocytes are able to take up this excess K+ and move it via their gap junctions either out into the circulation via the astrocytic end-feet or to an area of the brain lacking K+ (Wallraff et al. 2004). Genetic deletion of the Kir4.1 channel from astrocytes has a dramatic effect in mice. The mice only live 25 days and suffer from seizures, ataxia and tremor. Electrophysiological studies in these mice reveals significant impairment of potassium uptake by astrocytes, decreased spontaneous action potential frequency and amplitude, and increased LTP (Djukic et al. 2007). Other potassium channels expressed by astrocytes include the BK (also known as slo-1 or MaxiK), which is polarized to the end-feet (Price et al. 2002), and a family of potassium channels called the tandem-pore 2P channels, named because they have two pore domains. There are numerous subtypes within this class of potassium channel that each has different properties. However, the recent discovery of this new and diverse class of potassium channels [TASK-1 (acid-sensitive) (Kindler et al. 2000), TASK-2 (high pH-activated), TASK-3 (acid-sensitive) and TREK-2 (mechanosensitive) (Skatchkov et al. 2006) and the presence of these 2p-domain potassium channels on astrocytes suggest a functional role in the potassium buffering function of astrocytes.

Ionic movement across cell membranes is commonly coupled to movement of water and to the maintenance of osmotic equilibrium. Net transport of water always has to be driven by osmotic forces due to solute movement as there is no primary active transport, ATP-driven, water pump (Kimelberg 2004). Most water movement into and out of cells occurs via water channels in the plasma membrane. These water channels are called the aquaporins and to date 11 subtypes have been found in mammals. Six aquaporins have been described in the rodent brain (AQP1, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 9) (Badaut et al. 2002). Of these, aquaporin 4 and 9 have been best described. Aquaporin 9 is found in periventricular glia suggesting that it contributes to water movement between the CSF and brain parenchyma. Aquaporin 4, however, is expressed by astrocytes in the neurovascular unit and is highly polarized to the end-foot membrane. Aquaporin 4 immunoreactivity is strongly expressed on the majority of the cerebrovasculature where it has been shown to bind to α-syntrophin (Wilcock et al. 2009, Amiry-Moghaddam et al. 2003, Amiry-Moghaddam et al. 2004a, Amiry-Moghaddam et al. 2004b, Camassa et al. 2015). Interestingly, when α-syntrophin is deleted in mice, aquaporin 4 is no longer localized to astrocytic end feet. The mislocalization of aquaporin 4 in the α-syntrophin knockout mice is associated with significant functional defects including prolonged seizure durations with slowed potassium kinetics in the brain extracellular space (ECS). Potassium clearance deficits are also observed in α-syntrophin deficient mice, where aquaporin 4 is not properly targeted to the cell membrane (5).

A common link between the Kir4.1, BK and aquaporin 4 channels at the astrocytic end-feet appears to be a shared anchoring protein, dystrophin 1. Brain expresses a short isoform of dystrophin 1 named Dp71 (48). Dp71 has been found to be involved in anchoring the Kir4.1, BK and aquaporin 4 channels (14, 27). Dystrophin 1 complexes with α-syntrophin forming the end-foot anchoring complex.

Glutamate homeostasis

Another critical way that astrocytes affect neuronal excitability and signaling is through the regulation of extracellular glutamate levels using multiple excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT). Though essential for interneuronal communication within the brain, glutamate can become a powerful excitotoxin if levels are not held in check. Moreover, loss and/or disruption of end-feet, similar to that described above for VCID mouse models (Sudduth et al. 2017, Wilcock et al. 2009), are also found in disease models where excitotoxic damage is prominent (Gondo et al. 2014, Alvestad et al. 2013). Synapses are particularly vulnerable to excitotoxic insults and are lost at very early stages of cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer's disease. In some brain regions, like the hippocampus, the EAAT2 isoform (Glt-1, mouse homolog) mediates the bulk of astrocyte-dependent glutamate uptake and is therefore one of the most important mechanisms for protecting against excitotoxicity. Numerous studies show that the expression of EAAT2, or the functional uptake of glutamate through this transporter, is reduced in neurodegenerative diseases and/or animal models of disease including mild cognitive impairment and AD (Simpson et al. 2010, Masliah et al. 1996, Abdul et al. 2009), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Rothstein et al. 1992), Parkinson's disease (PD) (Chung et al. 2008), and Alexander's disease (Tian et al. 2010), to name a few. Moreover, signs of neural network hyperexcitability in many disease models are suppressed by genetic and pharmacological manipulations that promote glutamate uptake through EAATs, leading to the improved structural integrity and viability of neurons (Sheldon & Robinson 2007).

Intracellular mechanisms that negatively regulate EAAT2/Glt-1 expression, including the calcineurin/Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells (NFAT) (Sama et al. 2008), are found at elevated levels in astrocytes associated with AD pathology (Abdul et al. 2009), PD (Caraveo et al. 2014), excitotoxic injury (Neria et al. 2013), and/or traumatic brain injury (Furman et al. 2016). In mouse models of AD, inhibition of NFAT activity, selectively in astrocytes, restored EAAT2/Glt-1 expression, quelled neuronal hyperexcitability, and improved synaptic function and cognition (Furman et al. 2016, Sompol et al. 2017). While EAAT2 levels have yet to be systematically investigated in conjunction with small vessel damage associated with VCID, recent evidence from our labs shows that activated astrocytes enveloping microinfarcts express high levels of a proteolyzed, activated form of calcineurin (Pleiss et al. 2016), suggesting that the expression/function of EAAT2 in these regions may be adversely affected. Ongoing work in our laboratories is investigating this possibility and determining whether astrocyte dependent glutamate dysregulation is a key feature of VCID mouse models unpublished data).

Dementia-related astrocytic end-foot disruption

Significant disruptions of astrocytic end-foot function have been reported in many neurological conditions including ischemia (Frydenlund et al. 2006), brain tumors (Saadoun et al. 2003), epilepsy (Eid et al. 2005) and brain contusion (Saadoun et al. 2003). In the course of our own research, we have found similar astrocytic end-foot disruption in mouse models of AD, human AD with CAA, and a mouse model of VCID (Wilcock et al. 2009, Sudduth et al. 2017).

CAA

CAA defines the deposition of amyloid in the brain vasculature; primarily smaller arteries and arterioles. Our studies have shown that high levels of CAA, whether in a mouse model of amyloid deposition or in human AD brain, results in a decrease in the numbers of astrocytic processes contacting the vasculature in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Clasmatodendrosis is the term given to degenerated astrocytes that has primarily been demonstrated in Binswanger's disease, a form of VCID characterized by diffuse white matter lesions (Akiguchi et al. 1997). In our mouse and human studies, we examined astrocytic end-foot changes in more detail by examining the levels of channels known to be polarized to the end-foot; aquaporin 4 water channel and several potassium channels. Aquaporin-4 is a water channel highly polarized to the astrocytic end-feet (Yang et al. 1995). Transgenic mice with high levels of CAA have significant reductions in aquaporin-4 positive staining associated with the blood vessels. Interestingly, we showed that there was no change in total protein expression or gene expression of aquaporin-4, suggesting that the effect is specific to the distribution of aquaporin 4 protein. Astrocytic end-feet are highly enriched with the inward rectifying potassium channel, Kir4.1 (Higashi et al. 2001) and the BK calcium dependent potassium channel (Price et al. 2002), which are frequently co-anchored with aquaporin-4. Kir4.1 and BK gene and protein expression were significantly decreased in human AD and transgenic mice with high levels of CAA compared to low levels of CAA. (Wilcock et al. 2009). To confirm that the BK and Kir4.1 changes were not indicative of a more global decrease in potassium channel expression, we examined Kv1.6 levels. The voltage gated, delayed rectifier Kv1.6 channel expression, which is globally distributed on astrocytes (Smart et al. 1997), was not altered in any of the mouse strains or in the AD brain, irrespective of CAA levels. Overall, we concluded that CAA may significantly contribute to the observed NVU pathology and may directly alter neuronal excitability through changes in astrocytes channels and function (Wilcock et al. 2009).

VCID

Our group has been developing the hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) model that models multiple VCID pathologies including neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment and blood–brain barrier breakdown culminating in microhemorrhages throughout the cerebral cortex and, less frequently, hippocampus (Sudduth et al. 2013). HHcy is induced through dietary modification that eliminates vitamins B6 and B12, as well as folic acid, from the mouse chow, which are essential co-factors for the enzymes responsible for the clearance of Hcy. To determine astrocytic changes in our HHcy model, we examined the astrocytes, and astrocytic end-feet, at 6, 10 and 14 weeks on diet in wildtype mice. We performed histological and biochemical assessment of astrocytic end-foot markers, as well as behavior and neuroinflammation. Overall, we found astrocytic end-foot disruption characterized by a reduction in Dp71 dystrophin-1 labeling, concurrent with reduced vascular labeling for AQP4, and lower protein/mRNA levels for Kir4.1 and MaxiK/BK potassium channels. The first observed astrocytic changes occurred after 10 weeks on diet, and there was a further reduction at 14 weeks on diet. The expression of the end-foot channels was not reduced as a consequence of a reduced vessel density as we did not see any reduction in total vessel number labeled with collagen IV. Importantly, 10 and 14 weeks on diet is when we can observe significant cognitive impairment. These observations suggest that HHcy leads to astrocyte end-feet disruption, which is likely to have significant implications for both potassium homeostasis and neurovascular coupling.

An α-β dystroglycan complex anchors the astrocytic end-foot to the vascular basement membranes (figure 2) (Noell et al. 2011, Gondo et al. 2014). There are many proteinases that are capable of degrading such protein complexes, however, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) (Michaluk et al. 2007) appears to be a major degrading enzyme of the dystroglycans, specifically β-dystroglycan. MMP9 shows high expression levels in astrocytes (Yin et al. 2006). We have focused our studies on MMP9 both due to its high expression in astrocytes and also because MMP9 is regulated through the neuroinflammatory responses, specifically IL-1β and TNFα (Chakrabarti et al. 2006, Loesch et al. 2010, Klein & Bischoff 2011). In the HHcy mouse model, microglial activation was apparent at all time-points examined, including the earliest 6 week time-point, suggesting the pro-inflammatory responses and microglial activation (measured by CD11b immunohistochemistry) precedes astrocytic changes. We also showed that both IL-1β and TNFα expression, as well as IL-12 and IL-6, were increased at all time points examined. These data are consistent with our previous reports of induction of a pro-inflammatory state by HHcy (Sudduth et al. 2013, Sudduth et al. 2014). A detailed review focusing on the biology of MMP9 was published in 2016 (Weekman & Wilcock 2016).

Working hypothesis

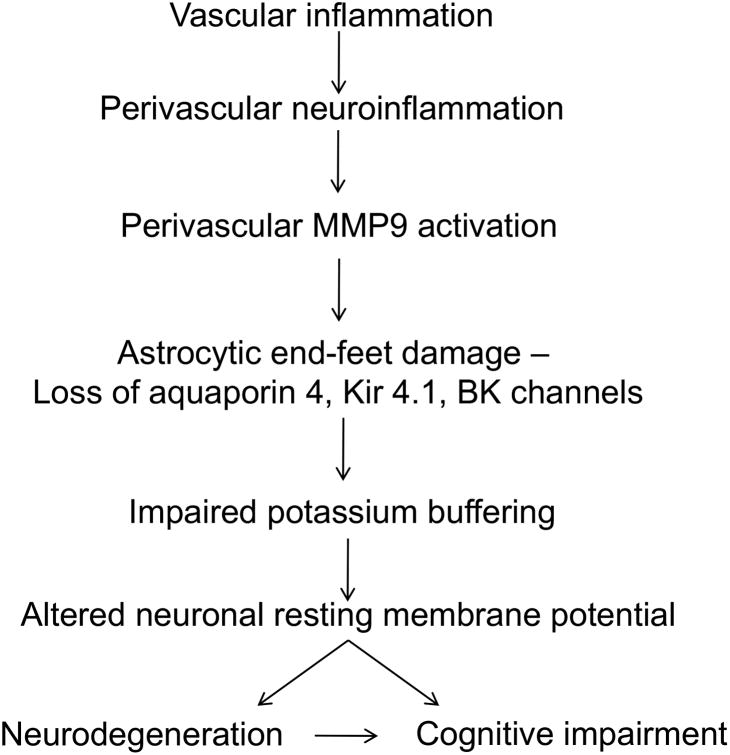

We hypothesize that perivascular neuroinflammation activates MMP9, which degrades the dystrophin-dystroglycan complex anchoring the end-foot to the basement membrane of the vasculature. This will lead to impaired neurovascular coupling and impaired potassium homeostasis, increasing neuronal excitability and ultimately leading to cognitive deficits (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Working hypothesis for the astrocytic contribution to VCID.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, neurovascular astrocytes have many critical functions in the brain, and their disruption likely has significant consequences on neuronal functioning. Further work specifically addressing the role of astrocytes in VCID, and specifically identifying functional consequences of our descriptive findings, is necessary to elucidate their role and ultimately identify potential therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

Work described in this review was supported in part by NIH grant NS079637 (DMW), AG027297 (CMN), and AG051945 (CMN).

List of abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- VCID

vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Dp71

dystrophin 1

- HHcy

hyperhomocysteinemia

- Aβ

amyloid-beta

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 beta

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- MMP9

matrix metalloproteinase 9

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- rmp

resting membrane potential

- Kir4.1

inward rectifying potassium channel 4.1

- AQP4

aquaporin 4

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests in the work presented here.

References

- Abdul HM, Sama MA, Furman JL, et al. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12957–12969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1064-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiguchi I, Tomimoto H, Suenaga T, Wakita H, Budka H. Alterations in glia and axons in the brains of Binswanger's disease patients. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1997;28:1423–1429. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.7.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvestad S, Hammer J, Hoddevik EH, Skare O, Sonnewald U, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Ottersen OP. Mislocalization of AQP4 precedes chronic seizures in the kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2013;105:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiry-Moghaddam M, Frydenlund DS, Ottersen OP. Anchoring of aquaporin-4 in brain: molecular mechanisms and implications for the physiology and pathophysiology of water transport. Neuroscience. 2004a;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiry-Moghaddam M, Otsuka T, Hurn PD, et al. An alpha-syntrophin-dependent pool of AQP4 in astroglial end-feet confers bidirectional water flow between blood and brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2106–2111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437946100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiry-Moghaddam M, Xue R, Haug FM, et al. Alpha-syntrophin deletion removes the perivascular but not endothelial pool of aquaporin-4 at the blood-brain barrier and delays the development of brain edema in an experimental model of acute hyponatremia. FASEB J. 2004b;18:542–544. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0869fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. 2011;42:722–727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badaut J, Lasbennes F, Magistretti PJ, Regli L. Aquaporins in brain: distribution, physiology, and pathophysiology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:367–378. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler JV, Munoz DG, Merskey H, Hachinski V. Fallacies in the pathological confirmation of the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1998;64:18–24. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camassa LM, Lunde LK, Hoddevik EH, Stensland M, Boldt HB, De Souza GA, Ottersen OP, Amiry-Moghaddam M. Mechanisms underlying AQP4 accumulation in astrocyte endfeet. Glia. 2015 doi: 10.1002/glia.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraveo G, Auluck PK, Whitesell L, et al. Calcineurin determines toxic versus beneficial responses to alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3544–3552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413201111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Zee JM, Patel KD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in TNF-stimulated neutrophils: novel pathways for tertiary granule release. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:214–222. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Chen LW, Chan YS, Yung KK. Downregulation of glial glutamate transporters after dopamine denervation in the striatum of 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:421–437. doi: 10.1002/cne.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukic B, Casper KB, Philpot BD, Chin LS, McCarthy KD. Conditional knock-out of Kir4.1 leads to glial membrane depolarization, inhibition of potassium and glutamate uptake, and enhanced short-term synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11354–11365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0723-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM, Nelson MT. Potassium channels and neurovascular coupling. Circ J. 2010;74:608–616. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid T, Lee TS, Thomas MJ, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Bjornsen LP, Spencer DD, Agre P, Ottersen OP, de Lanerolle NC. Loss of perivascular aquaporin 4 may underlie deficient water and K+ homeostasis in the human epileptogenic hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1193–1198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409308102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydenlund DS, Bhardwaj A, Otsuka T, et al. Temporary loss of perivascular aquaporin-4 in neocortex after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13532–13536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605796103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman JL, Sompol P, Kraner SD, et al. Blockade of Astrocytic Calcineurin/NFAT Signaling Helps to Normalize Hippocampal Synaptic Function and Plasticity in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurosci. 2016;36:1502–1515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1930-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondo A, Shinotsuka T, Morita A, Abe Y, Yasui M, Nuriya M. Sustained down-regulation of beta-dystroglycan and associated dysfunctions of astrocytic endfeet in epileptic cerebral cortex. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30279–30288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi K, Fujita A, Inanobe A, Tanemoto M, Doi K, Kubo T, Kurachi Y. An inwardly rectifying K(+) channel, Kir4.1, expressed in astrocytes surrounds synapses and blood vessels in brain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C922–931. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Katz B. The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of giant axon of the squid. J Physiol. 1949;108:37–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiwa NS, Garrard P, Hainsworth AH. Experimental models of vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Neurochem. 2010;115:814–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun S, Gold G, Bouras C, Giannakopoulos P, McGee W, Herrmann F, Michel JP. Immediate causes of death of demented and non-demented elderly. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2000;176:96–99. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapasi A, Schneider JA. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment, clinical Alzheimer's disease, and dementia in older persons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood-brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282:4067–4079. doi: 10.1111/febs.13412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg HK. Water homeostasis in the brain: basic concepts. Neuroscience. 2004;129:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler CH, Pietruck C, Yost CS, Sampson ER, Gray AT. Localization of the tandem pore domain K+ channel TASK-1 in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;80:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein T, Bischoff R. Physiology and pathophysiology of matrix metalloproteases. Amino Acids. 2011;41:271–290. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0689-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji P, Newman EA. Potassium buffering in the central nervous system. Neuroscience. 2004;129:1045–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa KM, Foster NL, Larson EB. Mixed dementia: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:2901–2908. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine DA, Langa KM. Vascular cognitive impairment: disease mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2011;8:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch M, Zhi HY, Hou SW, Qi XM, Li RS, Basir Z, Iftner T, Cuenda A, Chen G. p38gamma MAPK cooperates with c-Jun in trans-activating matrix metalloproteinase 9. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15149–15158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Alford M, DeTeresa R, Mallory M, Hansen L. Deficient glutamate transport is associated with neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:759–766. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaluk P, Kolodziej L, Mioduszewska B, Wilczynski GM, Dzwonek J, Jaworski J, Gorecki DC, Ottersen OP, Kaczmarek L. Beta-dystroglycan as a target for MMP-9, in response to enhanced neuronal activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16036–16041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria F, del Carmen Serrano-Perez M, Velasco P, Urso K, Tranque P, Cano E. NFATc3 promotes Ca(2+) -dependent MMP3 expression in astroglial cells. Glia. 2013;61:1052–1066. doi: 10.1002/glia.22494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusch C, Papadopoulos N, Muller M, et al. Lack of the Kir4.1 channel subunit abolishes K+ buffering properties of astrocytes in the ventral respiratory group: impact on extracellular K+ regulation. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1843–1852. doi: 10.1152/jn.00996.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA, Frambach DA, Odette LL. Control of extracellular potassium levels by retinal glial cell K+ siphoning. Science. 1984;225:1174–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.6474173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noell S, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Mack AF, Beedle AM, Satz JS, Campbell KP, Wolburg H, Fallier-Becker P. Evidence for a role of dystroglycan regulating the membrane architecture of astroglial endfeet. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:2179–2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss MM, Sompol P, Kraner SD, Abdul HM, Furman JL, Guttmann RP, Wilcock DM, Nelson PT, Norris CM. Calcineurin proteolysis in astrocytes: Implications for impaired synaptic function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:1521–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Ludwig JW, Mi H, Schwarz TL, Ellisman MH. Distribution of rSlo Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat astrocyte perivascular endfeet. Brain Res. 2002;956:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JM, Straub RW. The movement of potassium ions during electrical activity, and the kinetics of the recovery process, in the non-myelinated fibres of the garfish olfactory nerve. J Physiol. 1975;249:327–348. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1464–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205283262204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Krishna S. Water transport becomes uncoupled from K+ siphoning in brain contusion, bacterial meningitis, and brain tumours: immunohistochemical case review. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:972–975. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.12.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sama MA, Mathis DM, Furman JL, Abdul HM, Artiushin IA, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Interleukin-1beta-dependent signaling between astrocytes and neurons depends critically on astrocytic calcineurin/NFAT activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21953–21964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon AL, Robinson MB. The role of glutamate transporters in neurodegenerative diseases and potential opportunities for intervention. Neurochem Int. 2007;51:333–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard M, Nedergaard M. The neurobiology of glia in the context of water and ion homeostasis. Neuroscience. 2004;129:877–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JE, Ince PG, Lace G, et al. Astrocyte phenotype in relation to Alzheimer-type pathology in the ageing brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skatchkov SN, Eaton MJ, Shuba YM, et al. Tandem-pore domain potassium channels are functionally expressed in retinal (Muller) glial cells. Glia. 2006;53:266–276. doi: 10.1002/glia.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart SL, Bosma MM, Tempel BL. Identification of the delayed rectifier potassium channel, Kv1.6, in cultured astrocytes. Glia. 1997;20:127–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199706)20:2<127::aid-glia4>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Schneider JA, Wardlaw JM, Greenberg SM. Cerebral microinfarcts: the invisible lesions. Lancet neurology. 2012;11:272–282. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HM, Corriveau RA, Craft S, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia including Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2015;11:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sompol P, Furman JL, Pleiss MM, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT Signaling in Activated Astrocytes Drives Network Hyperexcitability in Abeta-Bearing Mice. J Neurosci. 2017;37:6132–6148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0877-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanimirovic DB, Friedman A. Pathophysiology of the neurovascular unit: disease cause or consequence? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1207–1221. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein S, Huttmann K, Gabriel S, Binder DK, Heinemann U, Steinhauser C. Impact of aquaporin-4 channels on K+ buffering and gap junction coupling in the hippocampus. Glia. 2011;59:973–980. doi: 10.1002/glia.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudduth TL, Powell DK, Smith CD, Greenstein A, Wilcock DM. Induction of hyperhomocysteinemia models vascular dementia by induction of cerebral microhemorrhages and neuroinflammation. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudduth TL, Weekman EM, Brothers HM, Braun K, Wilcock DM. beta-amyloid deposition is shifted to the vasculature and memory impairment is exacerbated when hyperhomocysteinemia is induced in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Alzheimer's research & therapy. 2014;6:32. doi: 10.1186/alzrt262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudduth TL, Weekman EM, Price BR, Gooch JL, Woolums A, Norris CM, Wilcock DM. Time-course of glial changes in the hyperhomocysteinemia model of vascular cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) Neuroscience. 2017;341:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R, Wu X, Hagemann TL, Sosunov AA, Messing A, McKhann GM, Goldman JE. Alexander disease mutant glial fibrillary acidic protein compromises glutamate transport in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:335–345. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d3cb52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff A, Odermatt B, Willecke K, Steinhauser C. Distinct types of astroglial cells in the hippocampus differ in gap junction coupling. Glia. 2004;48:36–43. doi: 10.1002/glia.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekman EM, Wilcock DM. Matrix Metalloproteinase in Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49:893–903. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock DM, Vitek MP, Colton CA. Vascular amyloid alters astrocytic water and potassium channels in mouse models and humans with Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler EA, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1398–1405. doi: 10.1038/nn.2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Ma T, Verkman AS. cDNA cloning, gene organization, and chromosomal localization of a human mercurial insensitive water channel. Evidence for distinct transcriptional units. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22907–22913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin KJ, Cirrito JR, Yan P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases expressed by astrocytes mediate extracellular amyloid-beta peptide catabolism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:10939–10948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2085-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]