Abstract

Despite recent advances in tissue engineered heart valves (TEHV), a major challenge is identifying a cell source for seeding TEHV scaffolds. Native heart valves are durable because valve interstitial cells (VICs) maintain tissue homeostasis by synthesizing and remodeling the extracellular matrix. In this study, the goal is to demonstrate that induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs) can be derived from iPSCs using a feeder-free protocol and then further matured into VICs by encapsulation within 3D hydrogels. The differentiation efficiency was characterized using flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry staining, and trilineage differentiation. Using our feeder-free differentiation protocol, iMSCs were differentiated from iPSCs and had CD90+, CD44+, CD71+, αSMA+, and CD45− expression. iMSCs underwent trilineage differentiation when cultured in induction media for 21 days. iMSCs were encapsulated in poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogels, grafted with adhesion peptide (RGDS), to promote remodeling and further maturation into VIC-like cells. VIC phenotype was assessed by the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), vimentin, and the collagen production after 28 days. When MSC-derived cells were encapsulated in PEGDA hydrogels that mimic the leaflet modulus, we observed a decrease in αSMA expression and increase in vimentin. In addition, iMSCs synthesized collagen type I after 28 days in 3D hydrogel culture. Thus, the results from this study suggest that iMSCs may be a promising cell source for TEHV.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, tissue engineering heart valves, mesenchymal stem cells, PEG, hydrogel

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Heart valve disease is an increasing clinical burden associated with high morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. The prevalence of valvular disease is expected to triple by 2050 due to age-dependent degeneration of heart valves and rheumatic fever in developing countries [3, 4]. Congenital heart defects also contribute to the incidence of heart valve disease and occur in 1 to 2% of births [5].

With limited biological diagnostics or drugs to prevent heart valve disease, treatment is restricted to valve repair, valve replacement, or the Ross procedure. Valve replacement is often performed in older patients using either a mechanical or biological valve prosthesis [6]. While these implants improve survival and quality of life, the lack of cells is considered to be the main source of failure for mechanical or glutaraldehyde-fixed biological valves [7] and the main reason for their inability to grow and repair. Without the potential for somatic growth, pediatric patients are required to undergo several surgeries for valve refitting [8, 9]. Tissue engineered heart valves (TEHV) can potentially address the shortcomings of current implants by incorporating biomaterials with autologous cells to enable growth and biological integration [10].

Native heart valves are durable because valve cells maintain tissue homeostasis [11], and without these cells, mechanical or biological prostheses fail over time [7]. Within the valve there are two primary cell types: valve endothelial cells (VECs) and valve interstitial cells (VICs). The primary focus of this study will be on VICs, which are found throughout the three layers of the leaflet and are known to synthesize and remodel the extracellular matrix [11–13]. These cells are believed to mediate long-term valve durability but could play a role in heart valve disease progression [7]. Other cell types such as fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells are also believed to populate the leaflets and play a role in active matrix remodeling [14].

Despite recent advances in the field of TEHV, the challenge to identify a suitable cell source for seeding 3D scaffolds still remains [7, 14]. To ensure the success of the TEHV, various cell types have been investigated. These include xenogeneic, allogenic, and autologous cells. Example of these cell types include bone marrow-derived cells, adipose-derived cells, and amniotic fluid cells from porcine, sheep, and human sources [15–17]. Xenogeneic and allogenic cells have been shown to evoke an immune response and may only be suitable for preclinical research [2, 18]. Meanwhile, autologous cells are the most appropriate cell source for seeding TEHV because they are patient-specific and depending on the cell source, they have the potential to be expanded and differentiated into other cell types.

More recently, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from various sources such as bone marrow (BM) and adipocytes have been investigated as a potential cell source for TEHV [14, 19, 20]. This is because of their similar characteristics to smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts and their ability to differentiate into several cell types. While initial studies demonstrated promising results, a major limitation of MSCs derived from sources like bone marrow is a decrease in differentiation potential with expansion of in vitro cultures [21–23], which results in limited therapeutic efficacy.

An alternative cell source that maintains a higher level of stemness and can be readily expanded for clinical translation is induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Previous studies have shown that MSCs derived from human embryonic stem cells have the same cell surface phenotype compared to BM-derived MSCs [22]. Meanwhile, iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) demonstrate trilineage differentiation [24]. With minimal senescence and higher telomerase activity potential [22, 25], iMSCs from iPSCs can be a potential cell source for TEHV. While only a few other groups have generated iMSCs from iPSCs, there is a need for safer transgene-free iPSCs and a feeder-free differentiation protocol for a more clinically translatable cell source.

While the outcomes of a TEHV depends on the cell source, the scaffold in which the cells are seeded can be utilized to direct cell phenotype and function. To recapitulate the ECM architecture in valve leaflets, a variety of natural and synthetic biomaterials have been explored. An ideal scaffold for TEHV is one that provides the biological cues to promote cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, and spreading [26]. The scaffold should also allow for the exchange of oxygen and cellular waste and stimulate ECM production and remodeling [27].

In particular, poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels can be designed to promote proper cell phenotype, proliferation, ECM production, and proteolytic degradation of the ECM. The goal is to generate a hydrogel that can enable cell adhesion and stimulate iMSCs to actively remodel the scaffold with ECM production [7]. Thus, the hydrogel network must accommodate the initial activation of iMSCs for active remodeling of the matrix, but over time, it must maintain cells in a quiescent fibroblast phenotype to prevent a pathological phenotype. Several groups have investigated PEG-diacrylate (PEGDA) as a hydrogel scaffold for TEHV applications [28–31]. Thus, we investigated the maturation of iMSCs into VIC phenotype by encapsulating iMSCs into a 3D PEGDA hydrogel mimicking the microenvironment found in native valve leaflets.

The objective of this study is to develop a feeder-free protocol for differentiating iMSCs from integration-free iPSCs and to introduce these cells into a three-dimensional hydrogel to promote VIC phenotype, and ECM matrix production and remodeling. We hypothesize a feeder-free protocol for differentiating embryonic stem cells can be modified to differentiate iPSCs into iMSCs. The introduction of iMSCs into a 3D hydrogel commonly utilized to study VIC phenotype and ECM production, will enable us to identify the potential of iMSCs as a cell source for TEHV.

2. Materials and Methods

All media components were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, US) unless otherwise stated.

2.1. iPSCs differentiation into iMSCs

The differentiation protocol used in this study was modified from a protocol originally used to differentiate human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) [32]. The differentiation process was modified to be feeder-free. Human integration-free iPSCs (supplementary information) were cultured for two passages in mTesR™1 media (StemCell Technologies) on Geltrex-coated plates (Gibco) before being harvested for MSC differentiation. Once confluent, iPSCs were passaged using collagenase IV at 200 U/mL for 5 minutes at room temperature. During differentiation, cells were cultured in differentiation media (DM), consisting of knock-out DMEM (KO-DMEM), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich, MO), 1 mM L-glutamine, 20% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Lifescience, UT), 1% non-essential amino acids, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin for 3 days in suspension petri dish (Corning, MA) to promote formation of cell aggregates. Afterwards, cells were transferred to gelatin-coated plates and cultured for 9 days. When cells became confluent, they were passaged by incubating 2 mg/mL of collagenase type II in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were maintained on gelatin-coated plates, plated at a seeding density of 2 × 104/cm2, and had media changed every 2 to 3 days. After this stage, cell media was replaced by iMSC media, which is composed of KO-DMEM, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Lifescience, UT), 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Media was changed every 2 days. Cell phenotype was characterized after the fourth passage.

2.2. Flow Cytometry

To characterize MSC surface antigens in iMSCs, cells were harvested, rinsed with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 0.5 × 106/mL for 10 minutes at room temperature. Afterwards, cells were incubated in 10% goat serum for 10 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted in BD Brilliant Flow Buffer and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were washed with flow buffer several times before being resuspended in 500 μL of flow buffer and analyzed using flow cytometer (BD LSR II, BD Bioscience, CA). The conjugated antibodies included mouse anti-human CD90 BUV395 (1:25, BD Biosciences), rat anti-human CD44 v450 (1:25, Tonbio), and mouse anti-human CD45 PE (1:25, Tonbio). For non-conjugated antibodies, rabbit anti-human CD71 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse anti-human αSMA (1:100, ABCAM) were used. Secondary antibodies included anti-rabbit and anti-mouse Alexa fluorophore 488 (1:300, Life Technologies). The panel of markers were controlled by unstained cells, human MSCs, and for CD45, a negative marker, fluorescein-5-Maleimide (1mg/mL) was used as positive control. For cells that were stained with primary and secondary antibodies, a similar protocol for conjugated antibodies was used. However, antibodies were diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and after cells were stained with primary antibodies, they were washed several times before incubation in the secondary antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature.

2.3. Trilineage Differentiation

To evaluate iMSC trilineage differentiation, cells were harvested and plated in triplicates at a seeding density 3.15 × 104 cells/cm2. For adipogenic differentiation, cells were cultured in iMSC media until 80–90% confluency, when the media was replaced by adipogenic induction media (Amsbio). To differentiate iMSCs into chondrocytes, a monolayer differentiation approach was utilized. Once cells reached 100% confluency in iMSC media, hMSC chondrogenic media (Vitrobiopharma) supplemented with 10% FBS was used. Osteogenic differentiation was conducted with cells at 100% confluency using osteoblast differentiation medium (Amsbio). Cells were cultured for 21 days with media changes every three days. Caution was necessary to not disturb cell monolayers. All differentiation medias were supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin. iMSCs maintained in iMSC media during the trilineage protocol was the negative control.

After differentiation, iMSCs treated with adipogenic and osteogenic induction media were fixed with 4% v/v paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. To stain for adipocytes, a working solution of 3 parts Oil Red O (Sigma) stock solution (0.3% w/v of Oil Redo O in isopropanol) with 2 parts DI water was filtered and incubated with cells for 5 minutes at room temperature. Multiple wash steps were necessary until washes were clear. The nuclei were stained with Hematoxylin following manufacturer’s protocol. For staining chondrocytes, toluidine blue stain (Sigma) was used after cells were fixed with cold methanol for 2 minutes. Cells were incubated with 0.5% v/v toluidine blue and washed with PBS. Cells treated with osteogenic media were stained with 1% w/v Alizarin Red S (Ricca Chemical Company) solution for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Multiple washes were needed after incubation in the staining solution. Samples were stored at −20°C until dye extraction. A microplate reader (BioTek Instruments) was used to measure absorbance at 492 nm, 603 nm, and 409 nm for Oil Red O, Toluidine Blue, and Alizarin Red S, respectively. Cells were imaged using the Olympus IX71 microscope.

2.4. Immunostaining and Cell Viability

To characterize cell phenotype of iMSCs in comparison to MSCs, cells were cultured on glass coverslips for 24 hours at a 2 × 104 cells/cm2 concentration. Immunofluorescence staining of αSMA and Phalloidin were performed following standard protocols. iMSCs were incubated with primary antibody mouse anti-human αSMA (1:250, Abcam), and secondary antibody anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 for secondary antibody (1:500). Rhodamine phalloidin at 25 μL/mL (Life Technologies) was used to stain for F-actin and DAPI (1 μg/mL; Sigma) stained the cell nuclei. For negative controls, only secondary antibody was incubated with cells. Cells were fixed with 4% v/v paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 followed by 1 hour incubation in 1% BSA, all samples were performed at room temperature. The primary and secondary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C and 2 hours at room temperature, respectively. Phalloidin and DAPI were added to cells for 20 minutes at room temperature. At each step, three washes with PBS were performed for 5 minutes each wash. Samples were imaged using Olympus IX71 microscope. Human MSCs were used a control cells and all samples were conducted as triplicates.

The ECM component was characterized in 3D PEGDA hydrogels by encapsulating 1 × 106 cells/mL iMSCs in 5% w/v PEGDA with 5 mM RGDS for 28 days. DAPI was used to image cell nuclei and fluorescein-5-Maleimide (10 μg/mL) was utilized to image the cell surface. Hydrogels were stained for collagen type I, αSMA, vimentin, periostin, and calponin using primary antibodies: mouse anti-human collagen type I (1:100; Abcam), mouse anti-human αSMA (1:100; Abcam), rabbit anti-human vimentin (1:100; Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-periostin (1:100; Abcam), and mouse anti-calponin (1:100; Abcam). The following secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (1:200), and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200). The protocol mentioned above for 2D cell culture was utilized for cell-laden hydrogels. iMSCs characterization was performed using an Olympus IX81 for confocal microscope imaging. To control for immunostaining, PEGDA blank hydrogels and secondary only antibody stained cell-laden hydrogels were used. Primary VICs (DV Biologics) and human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were utilized as a phenotype controls. The level of fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ. First a threshold was applied to images and then using particle analysis function in ImageJ the % area coverage of the marker of interest was determined.

2.5. Preparation of PEGDA hydrogels

Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA; ESI BIO) of molecular weight 3400 Da was used to make hydrogels. A prepolymer solution of 5% w/v PEGDA, 10 μM Eosin Y (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 0.375% v/v 1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NVP; Sigma), 1.5% v/v triethanolamine (TEOA; Sigma) was crosslinked using a white-light source (LED Light; Braintree Scientific, Inc.) for 1 minute. Hydrogels were soaked in PBS and then in media. Hydrogels with no cells were used for mechanical tests.

Hydrogel functionalization was performed by conjugating Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (RGDS) peptide (Cayman Chemical, MI) to acrylate-PEG-succinimidyl valeric acid (ACR-PEG-SVA; Laysan Bio, Inc., AL) in 50 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer solution at pH 8.5 (Sigma). RGDS peptide was incorporated into the PEG mesh network to enable cell adhesion. ACR-PEG-SVA was combined with RGDS at a 1:1.2 molar ratio (ACRY-PEG-SVA: RGDS) and reacted overnight at room temperature under constant agitation. PEG-RGDS was then dialyzed with MWCO membrane 3400 against 4 L of ultrapure water for 3 days with 4–5 water changes per day. Samples were then lyophilized into a dry powder. Conjugation was confirmed using NMR and MALDI-TOF.

To create cell-laden PEGDA hydrogels, a prepolymer solution of 5% w/v PEGDA with the white-light crosslinking components stated above was sterile-filtered using a 0.22-um syringe filter (EMD Millipore). Cells were then added to the prepolymer solution at 1.0 × 106 cells/mL (cell viability and mechanical testing) or 1.5 × 106 cells/mL (ECM production studies). To generate hydrogel disks, 15 μL of prepolymer solution was injected into molds consisting of a SigmaCote glass slide (Sigma), silicone spacers of 0.381 mm thickness (McMaster-Carr), and an 18-mm round coverslip (Fisherbrand). The prepolymer solution was crosslinked under LED white-light (Braintree Scientific) for 1 minute and gels were then soaked in PBS, followed by iMSC media. The media was changed every 2 days.

2.6. Characterization of PEGDA hydrogels

The overall properties of PEGDA hydrogels was characterized by compression testing using a TA Instruments ElectroForce 3100 Mini. Before performing compression testing, hydrogels were soaked in PBS for at least 24 hours and the diameter of each hydrogel was measured using a caliper. The thickness of the hydrogels was about 0.85 mm. Quasi-static compression testing was performed on a group of hydrogels, sample size n = 8, with a 1 N load and maximum displacement of 0.4 mm at a rate of 0.02 mm/sec. The linear portion of the stress-strain curve between 5–15% strain was used to calculate the least-squares fit slope to determine Young’s modulus.

2.7. Cell Viability

To determine cell viability, cell-laden hydrogels were stained with Live/Dead™ assay with calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer at 4 μM and 2 μM concentrations, respectively. Both components of Live/Dead™ assay were diluted in DAPI solution and incubated with hydrogels at 37°C for 20 minutes before imaging. Cell viability was measured at day 1 and day 7. Confocal microscopy (Olympus IX81) and ImageJ software was used to image hydrogels and quantify cell viability, respectively.

2.8. ECM Analysis

Before digestion of hydrogels, each construct was weighed, and excess water was removed by using weighing paper. PBE buffer was prepared by weighing out 7.1 g Na2HPO4 and 1.86 g Na2EDTA in 500 mL of ddH2O and pH corrected to 6.5. The solution was sterile-filtered with a 0.22 um filter before use. Constructs were digested and homogenized in a papainase solution composed of 1.67 mg per mL of L-Cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), PBE buffer, and 0.5% v/v papain (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated in this solution for 15–18 hours at 60°C. Samples were then frozen at −20°C until analysis. The cell density in each construct was quantified using the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® assay following manufacturer’s instructions.

To determine collagen content, samples were first homogenized in ultra-pure water and then equal volume of 10N HCl was added to a glass PTFE-lined vial. Samples were hydrolyzed for 3 hours at 120°C. Once cooled, 5 mg of activated charcoal was added to samples. The supernatant was recovered by centrifugation. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis. Using the manufacturer’s instruction for the hydroxyproline assay (Sigma-Aldrich), samples were mixed with Chloramine T/Oxidation buffer and diluted DMAB reagent. Samples were incubated in these two components for 90 minutes at 60°C before absorbance was recorded at 560 nm. Data was normalized to wet weight of hydrogel.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA). One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey-Kramer test was used to determine statistical significance in flow cytometry experiments for surface marker expression. Student t-tests were utilized for statistical analysis of absorbance levels in trilineage differentiation and cell viability assays and for marker quantifications. A one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s test was performed for collagen production. Sample size was determined by preliminary data and a Monte-Carlo simulation using Prism 7. In general, sample size n = 3–5 and technical replicates were used. Statistical significance was considered at a value of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. iMSCs derived from iPSCs using a feeder-free approach demonstrate phenotypic similarity to human MSCs

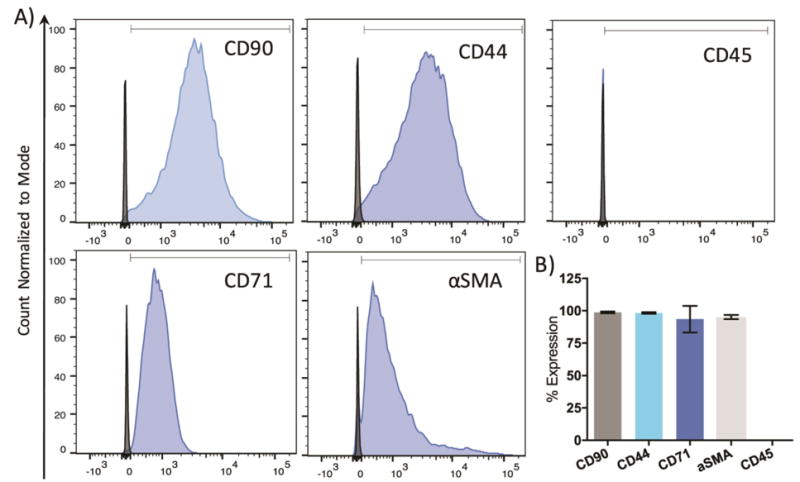

To address the need for a suitable cell source for seeding TEHVs, integration-free iPSCs were first generated from human dermal fibroblasts derived from a healthy child (Supplementary Figure 1), then differentiated into iMSCs using a feeder-free protocol. The surface marker profile of iMSCs was characterized by the expressions of CD90, CD44, CD71, αSMA, and CD45 using flow cytometry. Figure 1 shows that iMSCs have a 99.3%, 98.8%, 99.6%, and 95.9% positive expression of CD90, CD44, CD71, and αSMA, respectively. Meanwhile, there was a 0.020% expression of CD45, a hematopoietic marker. The expression of CD90+, CD44+, CD71+, αSMA+, CD45− phenotype suggests that iMSCs have a similar surface marker profile to MSCs.

Figure 1. Characterization of iMSCs differentiation efficiency via flow cytometry.

A) iMSCs were stained for positive expression of CD90, CD44, CD71, and αSMA surface markers. No expression of CD45 was observed. Blue peaks = stained cells. Black peaks = unstained cells. B) The expression of each marker was quantified by gating population of iMSCs and comparing to non-stained cells. N = 3–4.

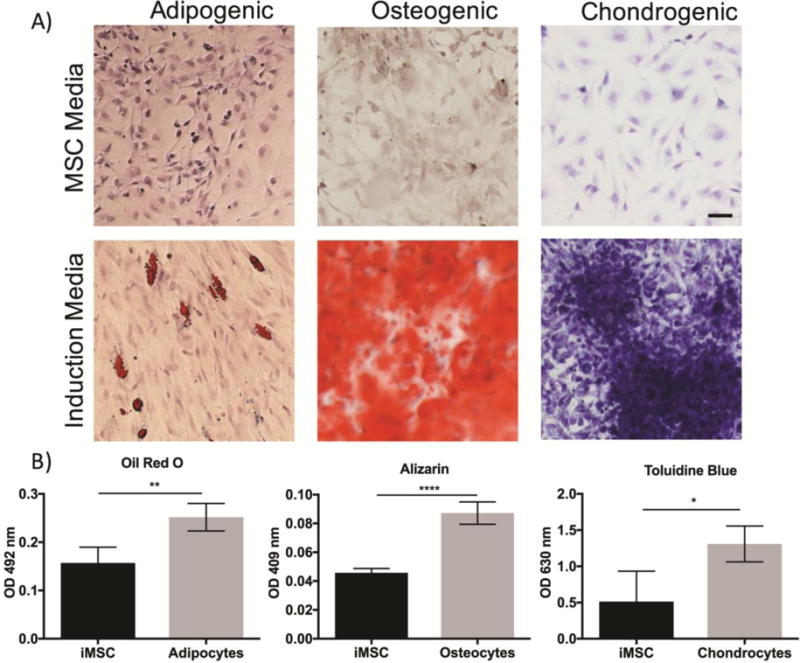

In addition to surface marker analysis, cells were cultured in adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic induction media to verify their multipotency. After 21 days in induction media, iMSCs demonstrated the capability to undergo trilineage differentiation (Figure 2). iMSCs cultured in adipogenic induction media led to intracellular lipid vesicles stained by Oil Red O dye. The levels of Oil Red O staining were quantified by measuring the absorbency at 492 nm. iMSCs treated with induction media resulted in a significantly higher absorbency of the dye compared to cells in MSC media. Furthermore, iMSCs cultured in osteogenic media led to statistically higher levels of extracellular calcium deposits, stained bright red using Alizarin Red S, as compared to cells in MSC media. Meanwhile, iMSCs cultured in chondrogenic induction began to form aggregates that stained purple-blue with toluidine blue stain, suggesting that iMSCs have differentiated into chondrocytes. The measured absorbency of toluidine blue dye was also statistically higher than cells without induction media.

Figure 2. Trilineage Differentiation of iMSCs.

A) iMSCs were cultured in adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic induction media for 21 days. Control iMSCs were cultured in MSC media. iMSCs demonstrate the ability to differentiate into adipocytes by evidence of intracellular fat deposits stained by Oil Red O. iMSCs cultured in osteogenic media led to high levels of extracellular calcium deposition stained in bright red using Alizarin Red S. High levels of toluidine blue staining in observed in iMSCs treated with chondrogenic media. B) The absorbency of each stain was quantified. Scale bar 50 μm. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; t-test.

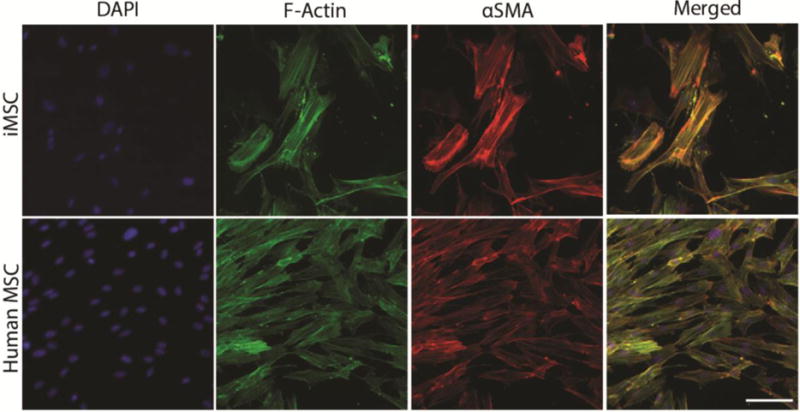

Furthermore, immunocytochemical staining was used to assess the localization of marker proteins αSMA and F-actin in iMSCs compared to control, human MSCs. Figure 3 shows iMSCs have stress fibers of αSMA and F-actin similar to human MSC controls. The cell morphology is also observed to be similar between iMSCs and human MSCs, where cells are fibroblast-like, bipolar, and elongated.

Figure 3. Characterization of iMSC phenotype.

iMSCs and human MSCs (control) were immunostained with DAPI, F-Actin, and αSMA after 24 hours. iMSCs had comparable expression of αSMA and F-actin stress fibers to human MSCs. Scale bar 50 μm.

3.2. Mechanical characterization of PEGDA hydrogels

Before encapsulating iMSCs in PEGDA hydrogels, RGDS an adhesion peptide sequence was conjugated to acrylate-PEG-succinimidyl valerate (SVA) with a molecular weight of 3.5 kDa using an established protocol [33]. This peptide sequence is conserved in fibronectin, an extracellular matrix protein that enables cellular interaction through integrin binding. The 1H NMR spectra in (supplementary figure 2) demonstrates that RGDS was conjugated to PEG via peaks at 4.4 nm, 4.2 nm, and 3.10 ppm. The conjugation was also verified by a shift in mass, 3673 Da for the acrylate-PEG-SVA to 3956 Da for PEG-RGDS, using MALDI-TOF (supplementary figure 3).

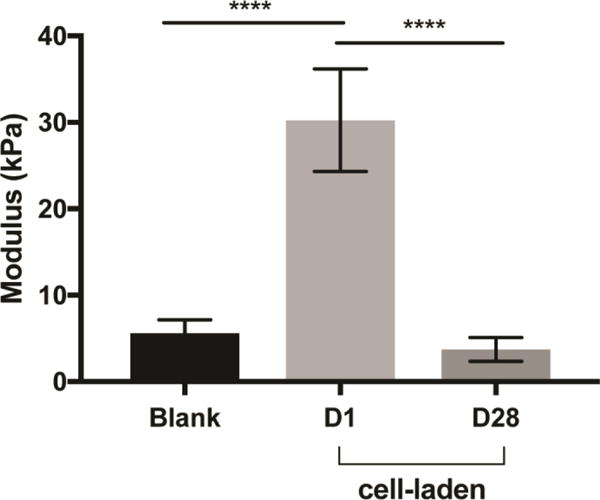

To determine the PEGDA hydrogel properties, PEGDA hydrogels with and without iMSCs were characterized through compression testing. Using the molds described under the methods section, PEGDA hydrogel discs of 5% w/v ratio following 1 minute of white-light exposure were created. Compression testing demonstrated the average modulus of PEGDA hydrogels at 1-minute white-light exposure to be 5.6 kPa. Meanwhile, cell-laden hydrogels had a significantly higher modulus of 30 kPa, and after 28 days of encapsulation, there was a significant decrease to 3.7 kPa. The overall modulus of blank PEGDA and 28 day hydrogels were still within the modulus of leaflet layers (~5–13 kPa) that native valve cells experience [34].

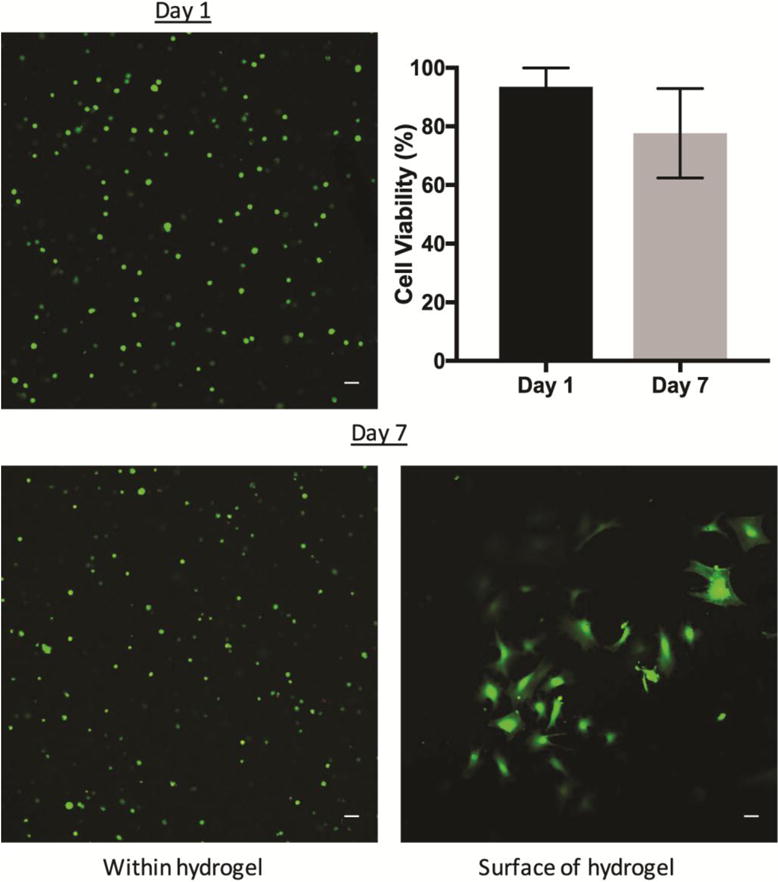

3.3. Cell Viability in PEGDA hydrogels

The cell viability of iMSCs encapsulated in 5% v/w PEGDA hydrogels with 5 mM RGDS was assessed after 1 and 7 days using the Live/Dead assay. After 1 day of encapsulation, iMSCs remained viable at 93% with a round cell morphology (Figure 5). Meanwhile, the cell viability decreased to 77% at day 7, though this was not statistically significant. In addition, there was a noticeable difference in cell morphology when iMSCs were encapsulated within the hydrogel or near hydrogel surface at day 7 as shown by calcein AM staining. Near the surface of the hydrogel, the cells showed signs of spreading and elongation. In contrast, within the hydrogel the cells-maintained a round morphology.

Figure 5. Cell viability of iMSCs encapsulated in 5% PEGDA hydrogels.

iMSCs were encapsulated into PEGDA hydrogels 5% w/v with 5 mM RGDS. Hydrogels were cultured for 1 or 7 days. Cell viability was 93% after 1 day of encapsulation and maintained at 77% after 7 days. There was no statistical significance between day 1 or day 7. Green is Calcein AM. Red represents ethidium homodimer. N = 3. Scale bar 50 μm.

3.4. Maturation of iMSC into VIC-like phenotype within PEGDA hydrogels

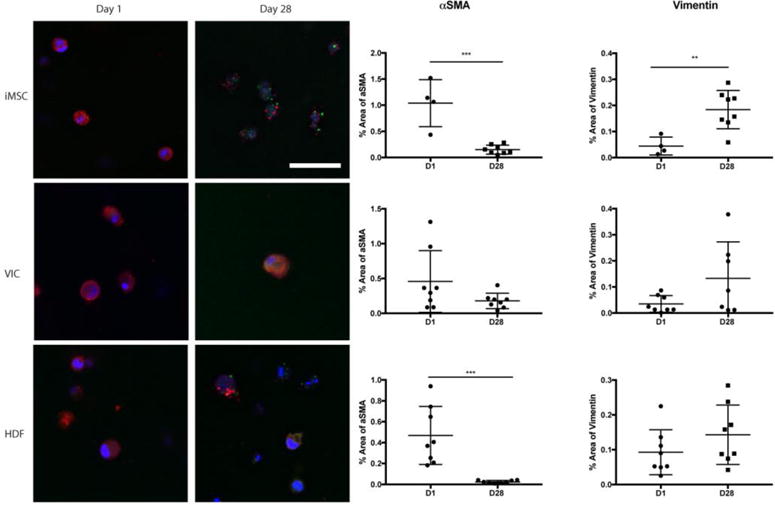

To assess iMSCs maturation into VIC-like cells, iMSCs were encapsulated in 5% w/v PEGDA hydrogels with 5 mM RGDS. Primary VICs and HDFs were also encapsulated into PEGDA as phenotype controls. As shown in Figure 6, cells within hydrogels were stained for αSMA and vimentin at 1 and 28 days post-encapsulation. At day 1, diffuse staining of αSMA (red) with no distinct stress fibers or staining for vimentin (green) was observed. At day 28 post-seeding, there was a distinct difference in staining patterns of αSMA and vimentin compared to day 1, where there was significantly less diffuse staining of αSMA and more staining for vimentin. In comparison, primary VICs and HDFs had higher expression of αSMA at day 1, followed by a decrease in expression by day 28. When the levels of αSMA and vimentin were compared at day 28 between the three cell types, iMSCs expression of αSMA and vimentin were most similar to VICs (supplementary figure 5).

Figure 6. iMSC expression of αSMA and vimentin after 28 days.

iMSCs, VICs, and HDFs were encapsulated into PEGDA hydrogels 5% w/v with 5 mM RGDS for 28 days. Fluorescence for αSMA and vimentin was quantified for each cell type at day 1 and day 28. Student t-test was conducted to comparing day 1 to day 28. DAPI=Blue; Vimentin= Green; αSMA = Red. Scale bar 50 μm. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 t-test; N = 4–8.

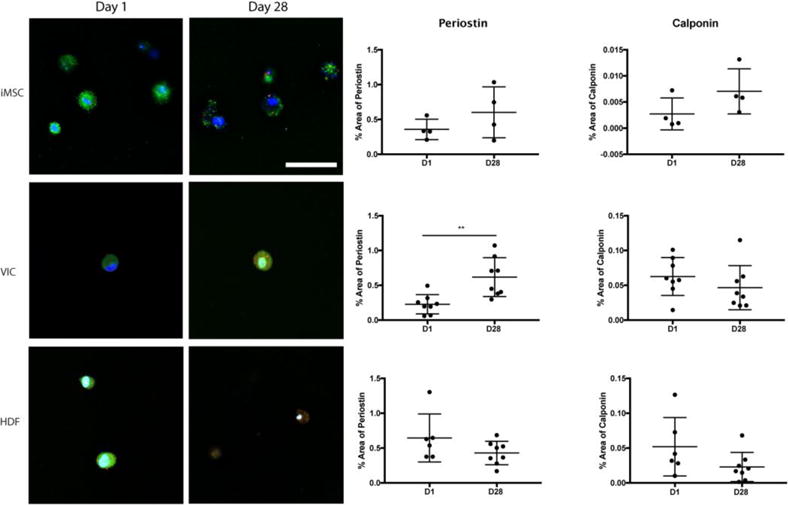

To further examine VIC-like differentiation, gels were stained with both calponin and periostin. While quantitative analysis of iMSCs showed that there was a small decrease in these 2 markers from day 1 to day 28, this was not statistically significant (Figure 7). VICs had a significant increase in periostin over time, while calponin remained at a similar level throughout the experiment. Meanwhile, HDFs showed no changes in either marker over time (Figure 7). When the levels of expression for periostin and calponin were compared at day 28 for all 3 cell types, iMSCs had similar levels of expression of periostin compared to VICs and HDFs; however, the level of calponin was significantly reduced compared to VICs (supplementary figure 4).

Figure 7. iMSC expression of periostin and calponin after 28 days.

All three cell types, iMSCs, VICs, and HDFs were encapsulated into 5% w/v PEGDA hydrogels with 5 mM RGDS for 28 days. Fluorescence for periostin and calponin was quantified for each cell type at day 1 and day 28. Student t-test was conducted to compare changes in expression over time. DAPI=Blue; Periostin= Green; Calponin = Red. Scale bar 50 μm. **p<0.01 t-test; N = 4–8.

3.5. Collagen deposition in 3D PEGDA hydrogels with encapsulated iMSCs

To determine if matured iMSCs had the capacity to deposit collagen, an important ECM component necessary to maintain valve homeostasis, hydrogels were fluorescently stained for collagen type I overlaid with the cell membrane (Figure 8). When iMSCs were initially encapsulated, there was minimal intracellular staining of collagen and some collagen deposits at the edge of the cell membrane. At the subsequent time point, collagen deposition surrounded the cell membrane as observed by the extracellular red staining. Quantitative analysis of collagen staining was significantly increased at day 28 compared to day 1. Meanwhile, there was no change in collagen production in either VIC or HDF hydrogels. When all 3 cell types were compared at day 28, iMSCs had significantly higher levels of collagen type I staining when compared to VICs and HDFs (supplementary figure 4).

Figure 8. iMSC Collagen Type I Deposition in PEGDA Hydrogels.

iMSCs, VICs, and HDFs were encapsulated into PEGDA hydrogels 5% w/v with 5 mM RGDS. Hydrogels were cultured for 1 and 28 days before being stained for collagen type I. Over time, iMSCs begin to deposit collagen. Student t-test was conducted to compare changes in expression over time. DAPI = Blue. Cell membrane = Green. Collagen type I= Red. ****p<0.0001 t-test; N = 3. Scale bar 50 μm.

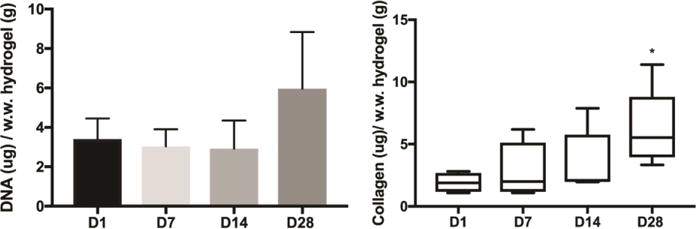

In separate experiments, the amount of collagen was quantitatively measured using the hydroxyproline assay, as hydroxyproline is a major component of collagen that stabilizes the helical structure (Figure 9). To control for changes in cell viability and/or number, total DNA was measured using Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® and used for normalization. While there was no significant change in DNA content with time, there was a statistically significant increase in normalized collagen deposition in day 28 hydrogels compared to day 1. However, no statistical difference was detected between day 1, 7, and 14 days.

Figure 9. Quantification of DNA content and collagen in cell-laden PEGDA hydrogels.

iMSCs were encapsulated into 5% w/v PEGDA hydrogels with 5 mM RGDS for 1, 7, 14, and 28 days. A) Using the PicoGreen assay, the DNA content remained unchanged at all time points. N = 4. B) Collagen content was determined by hydroxyproline assay and normalized by wet weight of hydrogel. *p<0.05 vs day 1; ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test. N = 4–5.

4. Discussion

A major shortcoming for current valve prostheses is the absence of cells required for active repair and remodeling of the scaffold [7]. Valve cells play an important role in the tissue homeostasis, in particular VICs, which synthesize and remodel the extracellular matrix [11–13]. In the current study, we attempted to generate a patient-specific cell source for adequate seeding of TEHVs. Cells were generated using a feeder-free differentiation protocol that had been previously used for embryonic stem cell differentiation [35], in order to differentiate induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs). iMSCs had similar expression in surface markers, phenotype, and functionality to adult human MSCs. These iMSCs were capable of trilineage differentiation as shown via staining and quantitative assays, and when cultured in a PEG hydrogel, differentiated further in to a VIC-like phenotype.

The advantage of using MSCs derived from integration-free iPSCs is the reduced risk associated with genome-integrating viruses [36]. Other protocols using iPSCs to derive iMSCs, use genome integrating viral vectors [37], which pose the risk of mutations that can alter differentiation potential and tumorigenesis, often caused by c-Myc oncogene reactivation [38]. Furthermore, using iPSCs as the main source for iMSCs presents the opportunity to differentiate iPSCs into other cell types from the germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. iMSC derived from iPSC has the ability to expand indefinitely without senescence and to differentiate into different cell types such as chondrocytes, osteoblasts, adipocytes, smooth muscle cells [24, 39]. In contrast, MSCs derived from sources like bone-marrow have limited differentiation potential and capabilities after extended in vitro culture [22, 23]. Thus, the feeder-free protocol and integration-free iPSCs reported here, presents advantages such as the inexhaustible autologous cell source, potential differentiation into several cells types, and the reduced risk for carcinogenicity compared to other protocols [22, 25, 39, 40].

After generating iMSCs, we hypothesized that introducing iMSCs into a 3D culture decorated with RGDS, an adhesion peptide, would promote cells to mature into VIC-like phenotype. A previous study by Zhang et al. demonstrated that RGDS concentration can regulate VIC phenotype [28]. Furthermore, VICs encapsulated within degradable PEG-RGDS hydrogels for 21 days produced ECM such as fibronectin and collagen type I, suggesting that RGDS is an important peptide for regulating and promoting VIC phenotype and ECM production [28]. Before encapsulating iMSCs, we first characterized the properties of the PEGDA hydrogels to verify that it closely mimicked the microenvironment in native valve leaflets. Using compression testing, the Young’s modulus of PEGDA blank hydrogels was within the physiological modulus of 5–13 kPa [34], interestingly there was an increase in modulus after cell encapsulation. A few possible reasons for a 6-fold increase could be due to the formation of a denser polymer network surrounding cells and the simple fact that cells contribute to a higher modulus. After 28 days, the modulus decreased either because of non-enzymatic degradation of PEGDA or cell death. Based on previous studies the modulus of heart valve leaflets is estimated to about 2 MPa and 15 MPa in the radial and circumferential direction, respectively [41, 42]. While this is several orders of magnitude higher than our study, the hydrogels utilized here were not intended to replicate the overall leaflet modulus but rather the microenvironment in which the valve cells experience.

The viability of iMSCs was characterized using Live/Dead assay. iMSCs encapsulated into PEGDA hydrogels demonstrated over 93% cell viability after day 1, this value then decreased to about 77% after 7 days in culture. A possible reason for the decrease in cell viability is the exposure to free radical from the polymerization process [43]. Furthermore, there was a distinct difference between cells on the surface compared to those encapsulated in the hydrogel. This difference can be explained by the fact that iMSCs may have been unable to spread through a non-degradable hydrogel, resulting in a round morphology. Thus, we also created a hydrogel containing a slow-degrading PEG-LGPA-PEG sequence (MALDI-TOF shown in Supplementary figure 5) [44], iMSCs did not assume a spindle-like morphology but rather formed large aggregates of cells, either through proliferation or migration, both of which are not favorable for a tissue engineered heart valve scaffold (Supplementary figures 6, 7, & 8). The LGPA linker was chosen due to slower degradation kinetics as linkers such as GPQ degrade on the order of days and were likely unfavorable. Additionally, we examined the mechanical properties of the degradable hydrogel (Supplementary figure 9) and found that these hydrogels at baseline were much softer than non-degradable hydrogels. Thus, future studies will examine degradation linkers of different rates or a combination of degradable natural polymers, to generate a more suitable 3D environment for iMSCs to spread and mature into VICs.

VICs are known to be a heterogeneous cell population with various sub-phenotypes that can resemble fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and MSCs [11, 12, 45]. Previous studies have demonstrated that VICs can be categorized into several phenotypes such as embryonic progenitor MSCs, quiescent VICs, activated VICs, progenitor VICs, and osteoblastic VICs [45]. The ideal phenotype for TEHVs is one that can be initially activated to remodel the scaffold and then transition into a quiescent phenotype, where cells maintain the scaffold structure. If VICs remain in an activated state, there could be issues with scaffold contraction and potential transdifferentiation of VICs into osteoblast-like cells [46, 47].

Activated VICs demonstrate high levels of αSMA with distinct fiber formation, which in our study was observed in the 2D culture when immunostaining for αSMA and F-actin and comparing it to human MSCs. At the initial encapsulation of iMSCs into 3D PEGDA hydrogels, there was diffuse staining of αSMA with no staining of vimentin present at day 1. There was a significant decrease in αSMA expression thereafter, and the staining transitioned from diffuse to punctate staining of αSMA after 28 days. The decrease in αSMA was accompanied by an increase in vimentin and low levels of periostin and calponin expression. Periostin is a protein involved in cell adhesion and robustly expressed in cardiac fibroblasts [48], and calponin is a calcium binding protein often found in smooth muscle cells or myofibroblast-like cells [49] and thus low levels of these proteins is desirable. These results suggest that by introducing iMSCs into a 3D hydrogel system, iMSCs express less αSMA, more of vimentin, and low levels of periostin and calponin. This can be interpreted as cells are transitioning from an activated phenotype to a more quiescent phenotype, which is characterized by the expression of vimentin, a marker for fibroblasts [14, 45].

To determine whether iMSCs are more VIC-like or fibroblast-like, the expression of αSMA, vimentin, periostin, and calponin was compared to VICs and HDFs after 28 days of encapsulation (supplementary figure 5). iMSCs had similar expression of αSMA, vimentin, periostin markers compared to VICs. The only significant difference in marker expression was calponin, which was higher in VICs. Although, the iMSCs were not identical to VICs, they may not need to be as VICs are heterogeneous in nature [50]. Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that it was feasible to use MSCs as a cells source for heart valve tissue engineering [51]. The results of that study showed MSCs having comparable levels of collagen, aSMA, and vimentin when introduced to different scaffolds [51].

While iMSCs appear to transition into a quiescent phenotype, it is important to discuss some of the limitations of the current hydrogel platform that could be resulting in the observed phenotype. iMSCs were cultured in non-degrading PEGDA hydrogels, which can result in a round-like morphology and “quiescent” state mainly because cells are unable to spread and degrade the hydrogel. However, when iMSCs were introduced into a slow-degrading PEGDA hydrogel cells did not spread throughout the hydrogel but rather formed aggregates of cells after 28 days of encapsulation (Supplementary Figure 6,7, and 8). In fact, the decrease in αSMA and increase in vimentin was not observed in the slow-degrading PEGDA hydrogels, further suggesting that the non-degrading hydrogel may be the more ideal environment for iMSCs to transition into a quiescent phenotype and produce collagen type I.

Collagen is a major extracellular matrix component that makes up the valve leaflet, along with proteoglycans and elastin [52]. Using immunostaining of iMSCs within hydrogels, there was little evidence of collagen type I at day 1, and as time progressed, collagen deposition significantly increased and was localized surrounding the cells. When compared to VICs and HDFs, iMSCs had significantly higher levels of collagen (supplementary figure 5). Quantitative hydroxyproline assay confirmed the immunostaining of collagen as there was significant increase at 28 days compared to day 1. Interestingly, while DNA levels rose progressively during the interim time points, it was not statistically significant. Again, similar to above, this could be due to the fact that the cells were unable to degrade the hydrogel and thus replace it with their own matrix, or that specific signals need to be added to the hydrogel to induce matrix secretion. Another explanation for an increase in DNA content at day 28 is that cells could have been in a “recovery state” post-encapsulation and only after 28 days were cells able to proliferate and produce collagen. However, a limitation of this study is that cells from the surface were not removed before homogenization. Overall, these findings suggest that iMSCs have the capacity to synthesize collagen type I when introduced into a 3D microenvironment mimicking the valve leaflet layers.

In future studies, we plan to investigate the potential for iMSCs to produce proteoglycans, elastin, and secrete matrix metalloproteinases. The use of PEGDA is to demonstrate, that as a simplified model, iMSCs can progress towards a VIC-like phenotype. However, further work is necessary to study these cells long-term as a potential cell source for tissue engineering. The role of mechanical stimuli is also worth investigating as it is a known to impact VICs phenotype and function [11].

5. Conclusion

Developing a suitable cell source for tissue engineering is a critical component for the success and durability of TEHVs. In this study, we attempt to address this problem by differentiating iMSCs from iPSCs and then further maturing these cells into VIC-like cells by introducing these to a 3D culture designed to mimic the layers of the valve leaflets. First, a modified differentiation protocol was utilized to differentiate into iMSCs using a feeder-free approach. Next, the PEGDA hydrogel was characterized and tuned to match the mechanical properties observed in valve leaflets. iMSCs were then encapsulated into PEGDA hydrogels to study the effects of a 3D culture in the maturation of iMSCs into VIC-like cells. Encapsulated iMSCs demonstrated a transition from an activated VIC-like phenotype to a more quiescent state. In addition, collagen deposition was identified in cell-laden PEGDA hydrogels, corresponding to the potential use of iMSCs as a cell source for TEHV. As such, these experiments contribute a potential new cell source for addressing the need of a suitable cell source as well as highlight the importance of a 3D culture environment to influence cell phenotype and function.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4. Mechanical properties of PEGDA hydrogels.

Compression testing was used to determine the bulk modulus of 5% v/w PEGDA hydrogels with 5mM RGDS, crosslinked with white-light for 1-minute. The elastic modulus in PEGDA only hydrogels was an average of 5.6 kPa. While cell-laden PEGDA hydrogels had a modulus of 30 kPa, which decreased to 3.7 kPa after 28 days. ****p<0.0001; N = 8 –10.

Statement of Significance.

Developing a suitable cell source is a critical component for the success and durability of tissue engineered heart valves. The significance of this study is the generation of iPSCs-derived mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs) that have the capacity to mature into valve interstitial-like cells when introduced into a 3D cell culture designed to mimic the layers of the valve leaflet. iMSCs were generated using a feeder-free protocol, which is one of the major advantage over other methods, as it is more clinically relevant. In addition to generating a potential new cell source for heart valve tissue engineering, this study also highlights the importance of a 3D culture environment to influence cell phenotype and function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Betkowski Family Research Fund, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship, NRSA NIH F31 Predoctoral fellowship, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Goizueta Foundation to A.L.Y.N, and the Petit Scholar Program to S.L. The authors thank Jiahui Zhang for assisting with peptide conjugation and characterization. This research project was supported in part by the Emory University Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core of the Emory+Children’s Pediatric Research Center, supported in part by the Emory Flow Cytometry Core and the Emory Comprehensive Glycomics Core, both part of the Emory Integrated Core Facilities (EICF) and are subsidized by the Emory University School of Medicine. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, C. American Heart Association Statistics, S. Stroke Statistics Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jana S, Lerman A. Bioprinting a cardiac valve. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(8):1503–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takkenberg JJ, Rajamannan NM, Rosenhek R, Kumar AS, Carapetis JR, Yacoub MH, D. Society for Heart Valve The need for a global perspective on heart valve disease epidemiology. The SHVD working group on epidemiology of heart valve disease founding statement. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2008;17(1):135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marijon E, Mirabel M, Celermajer DS, Jouven X. Rheumatic heart disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):953–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman J. The global burden of congenital heart disease. Cardiovascular journal of Africa. 2013;24(4):141–5. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2013-028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimtoola SH. Choice of prosthetic heart valve for adult patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(6):893–904. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacks MS, Schoen FJ, Mayer JE. Bioengineering challenges for heart valve tissue engineering. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2009;11:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alsoufi B. Aortic valve replacement in children: Options and outcomes. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2014;26(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henaine R, Roubertie F, Vergnat M, Ninet J. Valve replacement in children: a challenge for a whole life. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105(10):517–28. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendelson K, Schoen FJ. Heart valve tissue engineering: concepts, approaches, progress, and challenges. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2006;34(12):1799–819. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9163-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chester AH, El-Hamamsy I, Butcher JT, Latif N, Bertazzo S, Yacoub MH. The living aortic valve: From molecules to function. Global cardiology science & practice. 2014;2014(1):52–77. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chester AH, Taylor PM. Molecular and functional characteristics of heart-valve interstitial cells. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 2007;362(1484):1437–43. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoen FJ. Future directions in tissue heart valves: impact of recent insights from biology and pathology. The Journal of heart valve disease. 1999;8(4):350–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jana S, Tranquillo RT, Lerman A. Cells for tissue engineering of cardiac valves. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. 2016;10(10):804–824. doi: 10.1002/term.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Xiao DZ, Wang YG, Shan ZX, Liu XY, Lin QX, Yang M, Zhuang J, Li YX, Yu XY. Fn14 Promotes Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Heart Valvular Interstitial Cells by Phenotypic Characterization. Journal of cellular physiology. 2014;229(5):580–587. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masoumi N, Larson BL, Annabi N, Kharaziha M, Zamanian B, Shapero KS, Cubberley AT, Camci-Unal G, Manning KB, Mayer JE, Jr, Khademhosseini A. Electrospun PGS:PCL microfibers align human valvular interstitial cells and provide tunable scaffold anisotropy. Advanced healthcare materials. 2014;3(6):929–39. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt D, Dijkman PE, Driessen-Mol A, Stenger R, Mariani C, Puolakka A, Rissanen M, Deichmann T, Odermatt B, Weber B, Emmert MY, Zund G, Baaijens FPT, Hoerstrup SP. Minimally-Invasive Implantation of Living Tissue Engineered Heart Valves A Comprehensive Approach From Autologous Vascular Cells to Stem Cells. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56(6):510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinoka T, Ma PX, Shum-Tim D, Breuer CK, Cusick RA, Zund G, Langer R, Vacanti JP, Mayer JE., Jr Tissue-engineered heart valves. Autologous valve leaflet replacement study in a lamb model. Circulation. 1996;94(9 Suppl):II164–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rippel RA, Ghanbari H, Seifalian AM. Tissue-engineered heart valve: future of cardiac surgery. World J Surg. 2012;36(7):1581–91. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1535-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber B, Emmert MY, Behr L, Schoenauer R, Brokopp C, Drogemuller C, Modregger P, Stampanoni M, Vats D, Rudin M, Burzle W, Farine M, Mazza E, Frauenfelder T, Zannettino AC, Zund G, Kretschmar O, Falk V, Hoerstrup SP. Prenatally engineered autologous amniotic fluid stem cell-based heart valves in the fetal circulation. Biomaterials. 2012;33(16):4031–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Copier J, Bodman-Smith M, Dalgleish A. Current status and future applications of cellular therapies for cancer. Immunotherapy. 2011;3(4):507–16. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung Y, Bauer G, Nolta JA. Concise review: Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward safe clinical products. Stem cells. 2012;30(1):42–7. doi: 10.1002/stem.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsara O, Mahaira LG, Iliopoulou EG, Moustaki A, Antsaklis A, Loutradis D, Stefanidis K, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, Perez SA. Effects of donor age, gender, and in vitro cellular aging on the phenotypic, functional, and molecular characteristics of mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20(9):1549–61. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian Q, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang HK, Wu X, Zhang Y, Lam FF, Kang S, Xia JC, Lai WH, Au KW, Chow YY, Siu CW, Lee CN, Tse HF. Functional mesenchymal stem cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells attenuate limb ischemia in mice. Circulation. 2010;121(9):1113–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabapathy V, Kumar S. hiPSC-derived iMSCs: NextGen MSCs as an advanced therapeutically active cell resource for regenerative medicine. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2016;20(8):1571–1588. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Xu B, Puperi DS, Wu Y, West JL, Grande-Allen KJ. Application of hydrogels in heart valve tissue engineering. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2015;25(1–2):105–34. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.2015011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen KT, West JL. Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2002;23(22):4307–14. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Xu B, Puperi DS, Yonezawa AL, Wu Y, Tseng H, Cuchiara ML, West JL, Grande-Allen KJ. Integrating valve-inspired design features into poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel scaffolds for heart valve tissue engineering. Acta biomaterialia. 2015;14:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benton JA, Fairbanks BD, Anseth KS. Characterization of valvular interstitial cell function in three dimensional matrix metalloproteinase degradable PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30(34):6593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durst CA, Cuchiara MP, Mansfield EG, West JL, Grande-Allen KJ. Flexural characterization of cell encapsulated PEGDA hydrogels with applications for tissue engineered heart valves. Acta biomaterialia. 2011;7(6):2467–76. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mabry KM, Lawrence RL, Anseth KS. Dynamic stiffening of poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels to direct valvular interstitial cell phenotype in a three-dimensional environment. Biomaterials. 2015;49:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C, Jiang J, Sottile V, McWhir J, Lebkowski J, Carpenter MK. Immortalized fibroblast-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells support undifferentiated cell growth. Stem cells. 2004;22(6):972–80. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali S, Cuchiara ML, West JL. Micropatterning of poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Methods Cell Biol. 2014;121:105–19. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800281-0.00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinderer S, Seifert J, Votteler M, Shen N, Rheinlaender J, Schaffer TE, Schenke-Layland K. Engineering of a bio-functionalized hybrid off-the-shelf heart valve. Biomaterials. 2014;35(7):2130–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, Golds K, Kundu P, Gold JD, Carpenter MK. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19(10):971–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou YY, Zeng F. Integration-free methods for generating induced pluripotent stem cells. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11(5):284–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang R, Zhou Y, Tan S, Zhou G, Aagaard L, Xie L, Bunger C, Bolund L, Luo Y. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells retain adequate osteogenicity and chondrogenicity but less adipogenicity. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:144. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0137-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7151):313–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajpai VK, Mistriotis P, Loh YH, Daley GQ, Andreadis ST. Functional vascular smooth muscle cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells via mesenchymal stem cell intermediates. Cardiovascular research. 2012;96(3):391–400. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber B, Emmert MY, Hoerstrup SP. Stem cells for heart valve regeneration. Swiss medical weekly. 2012;142:w13622. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasan A, Ragaert K, Swieszkowski W, Selimovic S, Paul A, Camci-Unal G, Mofrad MR, Khademhosseini A. Biomechanical properties of native and tissue engineered heart valve constructs. Journal of biomechanics. 2014;47(9):1949–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balguid A, Rubbens MP, Mol A, Bank RA, Bogers AJ, van Kats JP, de Mol BA, Baaijens FP, Bouten CV. The role of collagen cross-links in biomechanical behavior of human aortic heart valve leaflets–relevance for tissue engineering. Tissue engineering. 2007;13(7):1501–11. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant SJ, Nuttelman CR, Anseth KS. Cytocompatibility of UV and visible light photoinitiating systems on cultured NIH/3T3 fibroblasts in vitro. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11(5):439–57. doi: 10.1163/156856200743805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang F, Williams CG, Wang DA, Lee H, Manson PN, Elisseeff J. The effect of incorporating RGD adhesive peptide in polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel on osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26(30):5991–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu AC, Joag VR, Gotlieb AI. The emerging role of valve interstitial cell phenotypes in regulating heart valve pathobiology. The American journal of pathology. 2007;171(5):1407–18. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker GA, Masters KS, Shah DN, Anseth KS, Leinwand LA. Valvular myofibroblast activation by transforming growth factor-beta: implications for pathological extracellular matrix remodeling in heart valve disease. Circulation research. 2004;95(3):253–60. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136520.07995.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puperi DS, Kishan A, Punske ZE, Wu Y, Cosgriff-Hernandez E, West JL, Grande-Allen KJ. Electrospun Polyurethane and Hydrogel Composite Scaffolds as Biomechanical Mimics for Aortic Valve Tissue Engineering. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2016;2(9):1546–1558. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snider P, Standley KN, Wang J, Azhar M, Doetschman T, Conway SJ. Origin of cardiac fibroblasts and the role of periostin. Circulation research. 2009;105(10):934–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harhun MI, Huggins CL, Ratnasingham K, Raje D, Moss RF, Szewczyk K, Vasilikostas G, Greenwood IA, Khong TK, Wan A, Reddy M. Resident phenotypically modulated vascular smooth muscle cells in healthy human arteries. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(11):2802–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor PM, Batten P, Brand NJ, Thomas PS, Yacoub MH. The cardiac valve interstitial cell. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2003;35(2):113–8. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colazzo F, Sarathchandra P, Smolenski RT, Chester AH, Tseng YT, Czernuszka JT, Yacoub MH, Taylor PM. Extracellular matrix production by adipose-derived stem cells: implications for heart valve tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32(1):119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hinton RB, Yutzey KE. Heart valve structure and function in development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:29–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.