Summary

Introduction

While developing a subject-specific knee model, different kinds of data-inputs are required. If information about geometries can be definitely obtained from images, more effort is necessary for the in vivo properties. Consequently, such information are recruited from the literature as common habit. However, the effects of the combined sources still need to be evaluated.

Methods

This work aims at developing an intact native subject-specific knee model for performing a sensitivity analysis on soft-tissues. The impacts on the biomechanical outputs were analysed during a daily activity for which articular knee kinetics and kinematics were compared among the different configurations. Prior to the sensitivity analysis, experimental and literature data were checked for the model reliability.

Results

Average values of mixed sources allowed the agreement with experimental data for personalized outputs. From the sensitivity analysis, knee kinematics did not significantly change in the selected ranges of properties for the soft-tissues (in rotation less than 0.5°), while contact stresses were greatly affected, especially for the articular cartilage (with differences in the results more than 100%).

Conclusion

In conclusion, during the development of a personalized knee model, the selection of the correct material properties is fundamental because wrong values could highly affect the numerical results.

Level of evidence

III a.

Keywords: subject-specific, knee model, soft-tissues, material properties, finite element analysis

Introduction

Knee joint kinematics is the result of a complex roto-translation movement typical of the tibio-femoral and patella-femoral articulations. This movement depends on the shape of the femoral condyles, the tibial plateau and the patella. Moreover, it is also related to the morphology and to mechanical behaviour and properties of the soft tissues of the knee joint. In fact, the knee is characterized by an extrinsic stability due to the active constraints (muscles and tendons) and passive soft-tissues (menisci, retinaculum and ligaments) that surround it.

Numerical methods have been used for decades for the simulation of the biomechanical behaviour of the knee joint. Numerical methods are able to simulate knee biomechanics for various activities and configurations. Modern finite element models are usually based on medical scans and possess a high accuracy of anatomical realism fundamental for the development of appropriate, reliable and effective tools aimed at supporting clinically-tailored questions1. Besides the simulation of the native joints, models are widely used for the prediction of the effects of degenerative pathologies, traumatic events as well as surgical repair and replacement strategie2–8. In particular, they are used for subject-specific analyses and for guiding the surgical pre-planning phase by comparing the effect of different designs of knee prostheses on the same patient9–13.

During the development of a subject-specific knee model, different kinds of subject-specific data-inputs are required, such as bone anatomies and alignments, material properties of the bone and the soft-tissues, loads and boundary conditions describing the examined motor-tasks. Frequently, not all of these data are currently available, for example subject-specific soft-tissues material properties are hardly obtained in vivo. Consequently, it is a common procedure to integrate literature data with subject-specific information, i.e. derived by imaging segmentation, in order to develop knee models for collecting personalized outputs that could be used to address research and clinical questions14.

However, the effects of the differently mixed combinations of subject-specific and literature data still need to be evaluated.

For these reasons, this work aims at developing an intact subject-specific knee model in which values from the literature were used to describe its materials. Hence, a sensitivity analysis on this intact knee model was performed to check the potential impacts on the biomechanical outputs of the model induced by changes on the material properties. The outputs after the simulation of a daily activity were also compared to experimental and literature data for additional reliability of the model.

Materials and methods

Geometries

CT images of a right leg of a cadaveric specimen (man, 86-year-old, 77 kg, 183 cm, BMI 23) were considered to represent the geometry of the femur, tibia and patellar. The images were imported in an image processing software (Mimics 17.0; Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) and segmented in order to generate 3D structures of interest of the leg 3,8,9.

The images were obtained at 120 kV and 410 mA, with a slice thickness of 0.80 mm. Prior to the reconstruction, medical records of the donor showed that he had no known history of musculoskeletal problems at the investigated right knee joint. By observing the CT scans, the anatomical landmarks were defined and later used to align the leg15,16. In order to classify the position of the patella, BP index17 was used. Being the patella height equal to 0.805 of BP index, it can be classified as normal.

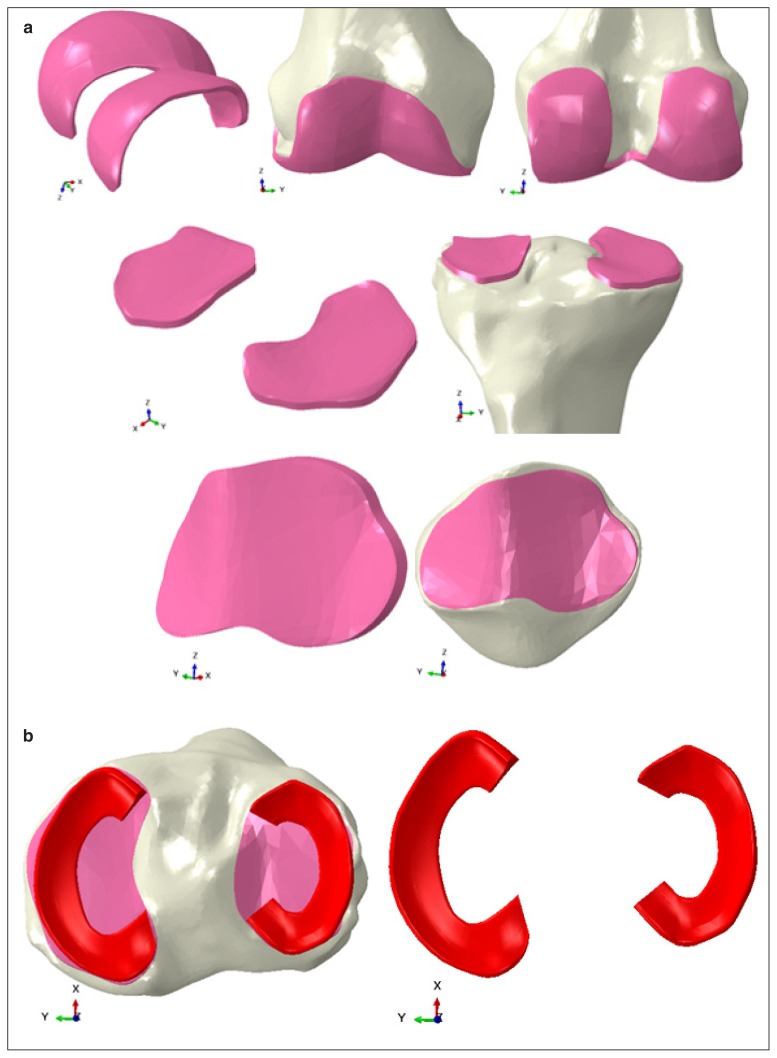

The area of insertion of the main ligaments of the knee was localized basing upon literature guidelines15,18–20. In particular, the medial and the lateral collateral ligaments, the cruciate ligaments and the patellar tendon insertions were identified for their proximal and distal positions on the femur, tibia, fibular and patellar bone. Fibula was used only for the placement of the insertion of the lateral collateral ligament, but it was not included in the intact knee model as 3D geometry. The reconstruction of the knee articular cartilage and of the menisci were performed following a novel technique21. In particalur, the cartilage layers were obtained as offsets of the distal femur, proximal tibial and posterior patella (Fig. 1a), thus were directly attached to the bone. The constant thickness for each cartilage region of interest was determined from the literature. In particular, following literature data, a mean thickness of 2.5 mm was used for the femoral and tibial layers22–25, while a constant thickness of 3 mm was adopted for the patellar layer22,26,27.

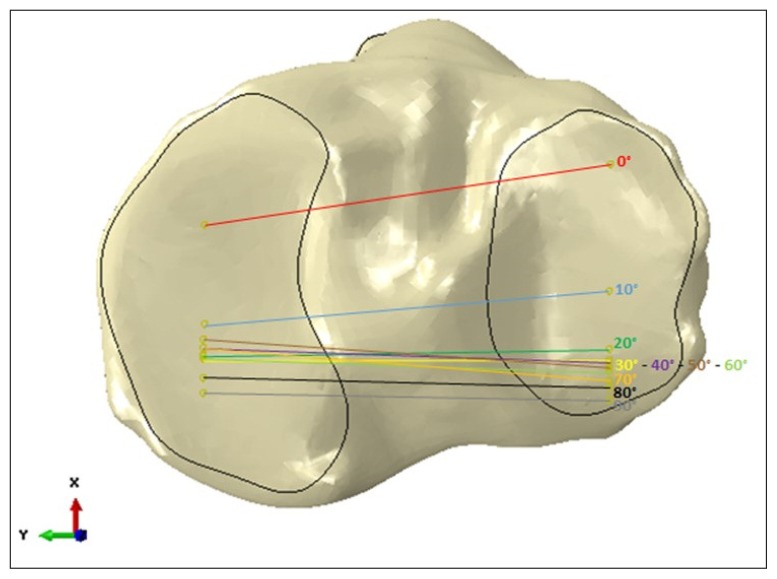

Figure 1.

a. Reconstruction of the cartilage layers of the femur, tibia and patella. The reconstruction was based on an offset of the bone shapes; b. reconstruction of the menisci geometries (red).

On the other hand, the menisci were designed trough a CAD extrusion following the proximal profile of the tibia. (Fig. 1b). Once finalized, the menisci were attached on the tibial cartilage layers by their horns and the external border.

Ligaments were considered as beams connected to the centroid of each previously determined insertion area according to previous literature studies8,11,14. For the cruciate ligaments and the lateral collateral ligament a circular section was considered, while a rectangular section was selected for better replicating the shape of the cross-section of the medial collateral ligament. Additionally, the sum of the cross-sections of the three bundles replicating the patella tendon is equal to the rectangular cross section of this ligament. The dimensions of the sections were selected according to the analysis of the medical images of the selected subject modeled in the full analyses.

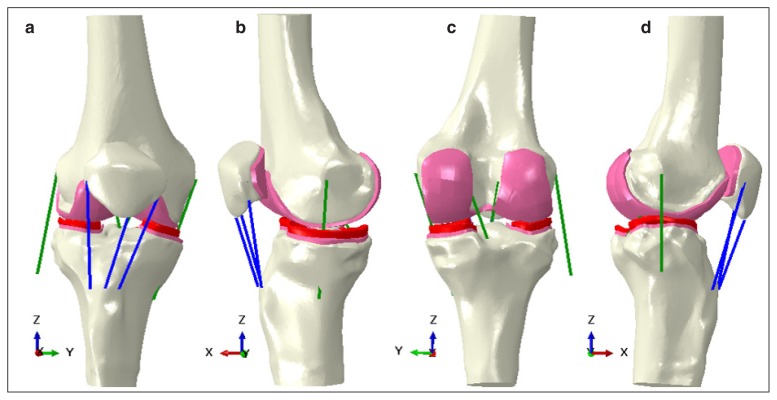

The full overview of the developed geometries are reported in Figure 1. The full model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Model assembly: a. anterior view; b. medial view; c. posterior view, and d. lateral view. The femoral, tibial and patellar bone are coloured in white, the articular cartilages in pink, the menisci in red, the cruciate and collateral ligaments in green and the patellar tendon bundles in blue.

Average materials properties for soft-tissues

A literature review, based upon experimental and numerical studies, was conducted in order to collect information about the average material properties of the menisci, the articular cartilage and the ligaments. For all these soft-tissues, a linear elastic model was assumed, in agreement with previous studies10,14.

For the menisci, only one experimental work28 was found describing them as transversely isotropic materials. Therefore, their elastic modulus has been evaluated as the average between the modulus in the circumferential direction and the moduli in the radial and axial directions.

For the articular cartilage layers, only a couple of experimental studies were reported. For this reason, the average value of the elastic modulus was calculated as the average of the moduli gathered only from the numerical works10,29–41.

For the cruciate ligaments, the average elastic modulus was calculated as the weighted average between the elastic moduli gathered from the experimental studies42–47.

On the contrary, for the collateral ligaments, the average elastic modulus was evaluated as the mean between the moduli of the numerical studies 10,39. All the values of the Poisson coefficient derive from the numerical work of Kwon et al.35.

Instead, regarding the patellar tendon (PT) material behaviour, the most frequently cited paper of Hashemi et al.48, that studied the mechanical properties of the PT through experimental tests on 20 specimens, was selected. An average elastic modulus of 507 MPa with Poisson coefficient of 0.45 was used.

The average values of Young’s modulus and Poisson coefficients selected for describing soft-tissues for the reference model are reported in Table I.

Table I.

Average material properties of the soft tissuesused for the sensitivity study.

| E [Mpa] | Poisson coefficient | |

|---|---|---|

| Menisci | 53 | 0,49 |

| Cartilages | 13 | 0,475 |

| ACL | 169 | 0,45 |

| PCL | 177 | 0,45 |

| MCL | 362 | 0,45 |

| LCL | 228 | 0,45 |

In the literature, bone was modelled similarly as rigid or linear isotropic material aiming for the development of computational knee models49. Moreover, the literature50,51 reported that the nature of the elastic properties assigned to the bones has only a marginal influence on final stress analysis. For these reasons, bones were also modelled as homogeneously isotropic linear elastic material10,40 and the adopted material properties were those of cortical bone: an elastic modulus of 20 GPa and Poisson’s ratio of 0.3.

Definition of the parameters of the sensitivity analysis

Due to the huge heterogeneity of the data collected from the literature, a large standard deviation characterized the mean value selected to describe the material behaviour of the menisci, the cartilage and the ligaments.

For this reason, the sensitivity analysis was set by changing the value of the material properties for each soft tissue based upon the obtained standard deviations. In particular, the lower value (later referred as Minus) and the maximum value (later referred as Plus) were calculated adding up or subtracting the standard deviation to the average value10,28–47.

In doing such selection of the values for the parameters of the sensitivity analysis and basing upon the literature review, it was not possible to identify a global range of properties characterizing the menisci that included data both from experimental and numerical studies. In fact, the values reported in the literature for numerical studies (range 45–61 MPa) were too far from the experimental ones (12 MPa) and lacks of sources information were present. Hence, it was necessary to introduce a further varying parameter for the menisci properties identification, as the literature review was based on only experimental data (later recalled as Minus and Plus) or only on numerical papers (later recalled as Num). Moreover, the average value of experimental studies has been obtained from transversal isotropic models using an equivalent formulation10,36,52,53.

Table II reported all the values to be attributed the Young’s modulus (MPa) and adopted during the sensitivity analysis.

Table II.

All the values attributed to the parameters varied (Young Modulus [MPa]): “Minus” indicates the minimum value of the range of values identified for each soft tissue, while “Plus” is the maximum value; “AVG” is the average value and “Num” reported the value from numerical studied introduced only for the menisci.

| Minus | AVG | Plus | Num | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menisci | 45 | 53 | 61 | 12 |

| Cartilages | 8 | 13 | 18 | |

| ACL | 93 | 169 | 245 | |

| PCL | 107 | 177 | 247 | |

| MCL | 320 | 362 | 404 | |

| LCL | 62 | 228 | 393 |

A statistical analysis software (Minitab 17 trial version, 2014) was used to develop the simulation plan and to analyse the effect of the changes in material properties on the biomechanical results. In detail, a full-factorial design was adopted considering for the cartilages and the ligaments three levels (Minus, AVG and Plus) and four levels for the menisci (Minus, AVG, Plus and Num). A total of 36 numerical simulations was consequently executed (Tab. III).

Table III.

The map of the performed simulations combining different values, as reported in Table II, for the properties of cartilage, menisci and ligaments.

| N | Cartilages | Menisci | Ligaments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minus | Minus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 | Minus | AVG | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 | Minus | Plus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 | Minus | Num | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 | AVG | Minus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 | AVG | AVG | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 | AVG | Plus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 | AVG | NUM | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 | Plus | Minus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 | Plus | AVG | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 | Plus | Plus | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 | Plus | Num | Minus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 13 | Minus | Minus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 14 | Minus | AVG | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 15 | Minus | Plus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 16 | Minus | Num | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 17 | AVG | Minus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 | AVG | AVG | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 19 | AVG | Plus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 | AVG | Num | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 21 | Plus | Minus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 22 | Plus | AVG | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 23 | Plus | Plus | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 24 | Plus | NUM | AVG |

|

|

|

|

|

| 25 | Minus | Minus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 26 | Minus | AVG | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 27 | Minus | Plus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 28 | Minus | Num | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 29 | AVG | Minus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 30 | AVG | AVG | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 31 | AVG | Plus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 32 | AVG | Num | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 33 | Plus | Minus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 34 | Plus | AVG | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 35 | Plus | Plus | Plus |

|

|

|

|

|

| 36 | Plus | Num | Plus |

Analysed task

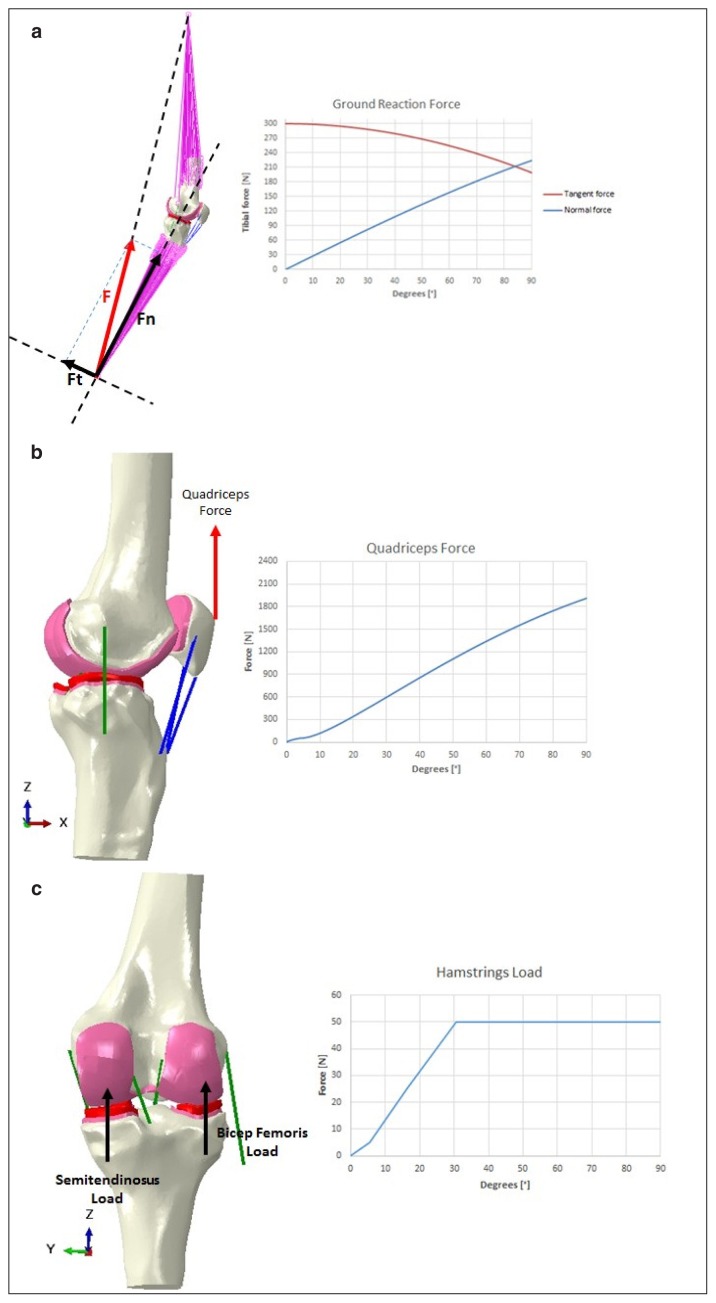

A loaded knee flexion up to 90° was considered for the reference model and for its comparison with literature studies in order to verify the model reliability. On the other hand, the sensitivity analysis was limited to a maximum flexion of 60° in order to reduce the computational time, but still to get the behaviour of all configuration for the maximum mean flexion reached during gait. External loads and boundary conditions were replicated from experimental tests54 and from already published numerical studies5,6,8, 9,60. Details of applied forces are reported in Figure 3. The femur was considered fixed while the tibia flexes around the epycondylar axis with force applied at the ankle. Quadriceps force was applied on the patella and two constant forces were replicating the contribution of the two hamstrings.

Figure 3.

Loads and constrains applied to the model to replicate the motion task: a. ground reaction forces have applied as tangent (red) and normal (blue) force components to the ankle while the femur is proximally constrained; b. quadriceps force (distally/ proximally oriented) is applied to the insertion of the quadriceps tendon on the patella; c. hamstrings are equally loaded (distally/proximally oriented).

An initial pre-strain10 was considered for every ligament that is meshed as a beam. All the other geometries were meshed with linear tetrahedral elements, after performing a convergence analysis and according to the previous work of Innocenti et al.10. The entire meshed model included a total of 180k elements.

A friction coefficient of 0.013,10,29 is considered for the contact among the cartilage layers and the menisci.

All simulations were dynamically performed by means of finite element analysis software (Abaqus-Explicit 6.12-1.0, Dassault systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France).

Model outputs

To check the reliability of the model, contact pressures on the femoral and the patellar cartilage layers and on the menisci, and tibiofemoral kinematics, such as the intra-extra rotation of the tibia, for the reference model, were compared to experimental results and data reported in the literature for similar configurations, loads and boundary conditions.

For the sensitivity analysis, the mean contact pressure, the contact area, and the magnitude of the contact force due to contact pressure on menisci and on patellar cartilage were investigated. Moreover, for the analysis of the kinematics, the mean value of intra-extra rotation and the range of the antero-posterior translation of the tibia and the medio-lateral translation of the patella were analysed.

Results

Reference model

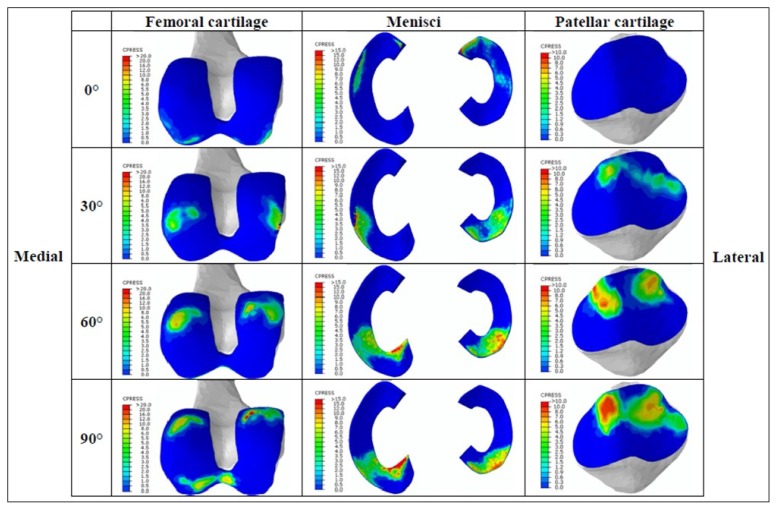

For the reference model, Figure 4 reported the contact pressure outputs for femoral cartilage, menisci, and patella for the different flexion angles.

Figure 4.

Contact pressure analysed on the distal femur, menisci and posterior patellar cartilage during the simulated flexion task for the subject-specific intact knee model. Each row represents different achieved knee flexion, while the columns indicate the different analysed regions of interest. In each cell, the left side represents the medial region while the right side represents the lateral region. Reported contact pressures results are indicated with colours from blue (0 MPa) to dark red (up to 20, 15, 10 MPa for femoral, tibial and patellar regions respectively).

The contact pressures on the femoral cartilage and on the menisci increased with the knee flexion reaching maximum values (greater than 15 MPa) already around 60 degrees of knee flexion. Regarding the contact pressure on the patellar cartilage, the maximum value was about 10 MPa and was also reached at 60 degrees of knee flexion.

Kinematics was in agreement with literature data57. In particular, Figure 5 shows the plotting of the medial and the lateral centroids of the pressure describing the correct femoral external rotation during flexion behaviour. Analysing Figure 5, after 20 degrees of flexion, the knee joint was posteriorly translating. Infact the lines joining the medial and the lateral contact pressure centroids were kept parallel up to 90 degrees of knee flexion. These results were in agreement with the literature work of Victor57 in which tibial intra-extra rotation trend, between 30 and 90 degrees of flexion, was also constant. Moreover, results from experimental tests performed on the same analysed specimen and for similar boundary conditions reported a similar internal/external kinematics trend with a range of 3.9 degrees of external rotation.

Figure 5.

Lateral and medial (right knee) centroid of pressure are plotted on the tibial plateu in function of the flexion angle (x positive anterior diction, y positive medial direction).

Furthermore, in agreement with the literature58, a posterior translation of the tibia relative to the fixed femur of 16 mm was observed and the patella shifted to the medial from lateral side with a range of about 3 mm59.

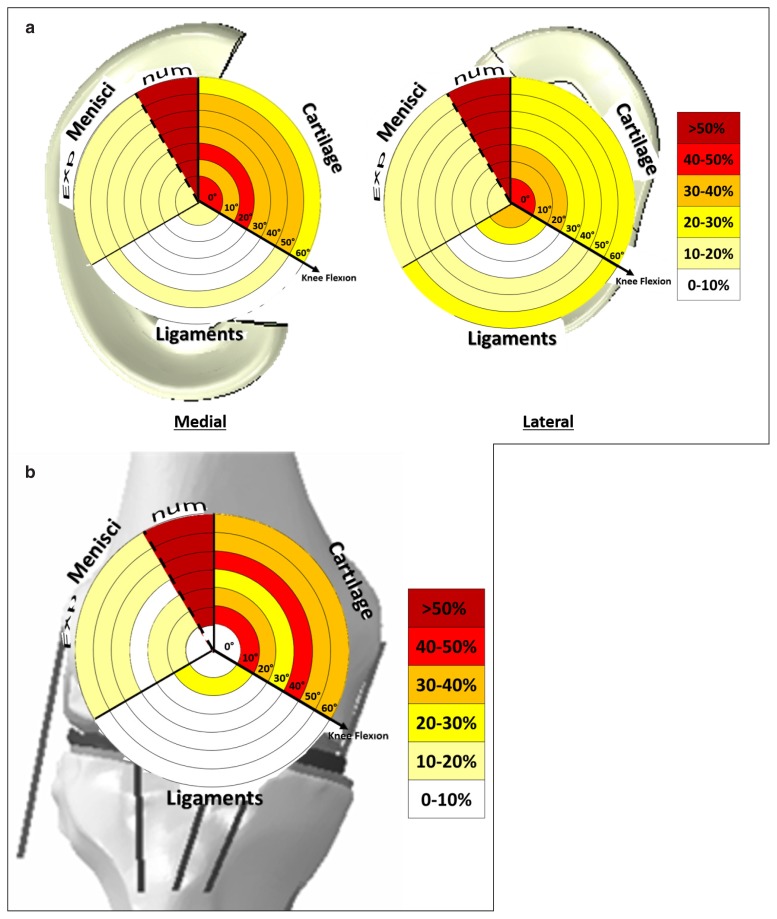

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis collected a huge amount of data outcomes. In order to represent, concisely and intuitively them, a novel graphical technique was used60. Through this graphical technique, on the background was described the analysed structure for which outputs were extracted. Different circular sectors, subdivided in regions related to the different varied parameters, were describing the effects on the outputs for different analysed flexion angles. In each sector, the maximal variation (in %), with respect to the average value, calculated on all the configurations, was reported (Tab. IV). Light colours represent no/low variation while red to dark-red indicate the maximum variations.

Table IV.

Average pressures value (MPa), for each flexion knee angle, for the medial and lateral menisci and for the patella.

| 0° | 10° | 20° | 30° | 40° | 50° | 60° | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Menisci | 1,9 | 2,2 | 2,5 | 2,9 | 3,5 | 4,0 | 4,7 |

| Medial Menisci | 2,4 | 2,4 | 2,7 | 2,8 | 2,8 | 2,8 | 3,6 |

| Patella | 0,0 | 0,5 | 1,2 | 1,2 | 1,7 | 2,0 | 2,9 |

Figure 6 reports the effects on the contact pressure distribution after the sensitivity analysis for the menisci and the patella.

Figure 6.

The alterations of the contact pressure on the medial and lateral menisci (a) and on the patella (b) due to the variation of the parameters in defining the cartilage, menisci and ligaments material behaviour. In the graphs, the results are compared for different analysed knee flexions (0–60 degrees of flexion). The alterations are expressed in percentage with respect to the average value calculated as average of the outputs in function of all the configurations for all the analysed knee flexions.

The outcomes showed that the main affecting parameters of the sensitivity analysis were the cartilage and the menisci, but only when they were characterized by values obtained from numerical works as reported in the literature. The range of values attributed to the cartilage could vary the pressure outputs up to 50% both for the menisci and the patella; however the menisci characterized by values of numerical studies could vary the contact pressure more than 100%.

The other parameters did not significantly impact on the final biomechanical outputs. The values selected for the menisci from experimental studies equally affected the medial and the lateral outputs maximum up to 19% and the patellar up to 15% independently by the knee flexion.

On the other hand, the stiffness of the ligaments mainly affected only the lateral meniscus pressure output and less the medial one.

Discussion

In the definition of a native intact knee model, the identification of the correct material behaviour of the involved structures is always a challenge for the consistency of the model outputs. Additionally, in case of subject-specific tailored questions, few approximations can unfortunately be formulated on the status of the subject’s tissues characteristics from imaging or palpation61,62. Hence, the literature becomes a fundamental alternative source of data.

Generalized inputs from the literature for material model and properties are ambiguous and their selection is highly delicate when discordant values are met during a literature review. In fact, even if the literature search can be based on similar filters, such as boundary conditions or subject’s gender and age, huge variability is usually observed. The difficulty, in selecting the right parameters for the description of a specific material, increases with the complexity of the chosen material model to describe it.

Depending on the research question, simplistic approaches adopted for bone modelling are still nowadays justified in order to reduce the computational time (and cost) especially for comprehensive knee models. However, if indications about justified assumptions are present, when soft-tissues need to be characterized in a knee model, no univocal guide is present in the literature. In fact, several testing approaches leading to different characterizations, even for the same soft-tissue, are present in literature studies. This finding generated concern on how discriminating similar or different soft-tissues behaviour was dependent to the testing approach. Even if literature search can be systematic and filtered on selected thresholds, it results anyhow in huge ranges of values characterizing each material model and properties.

For these reasons, it was decided to adopt the weighted mean or mean value to describe the behaviour of the soft-tissues structures in the developed reference model and consequently to consider the effect of the change of this value based on the calculated standard deviation in the sensitivity analysis.

Results reported in this work show that, assuming the material properties characterized by average literature data and using subject-specific geometries, personalized outputs can be obtained.

On the other hand, the sensitivity analysis shows that, first, the kinematics does not seem to be significantly affected by any of the changes of the parameters (less than 8% for anterio-posterior direction, less than 0.5 degrees for internal-external rotation, and around 10% for medial-lateral patellar translation). This outcome is also in agreement with a previous paper56 which reports that kinematics was not altered as much as kinetics for possible total knee arthroplasty (TKA) component misalignments.

Then, among the varied parameters, the main affecting one is the cartilage characterization. In fact, assuming the complete range of properties detected by literature, contact pressures changes can be up to 50% for both menisci and patella outputs. The results are independent by the knee flexion and the other contemporarily changed parameters. Moreover, values obtained from numerical studies to describe menisci behaviour should be avoided. In fact, they can alter the stresses outputs more than 100%.

On the other hand, changes of material for the soft-tissues do not significantly impact on the biomechanical outputs, especially for the ligaments. These results can be considered relevant especially for all those subject-specific models aimed to characterize the knee behaviour when a total knee arthroplasty is considered. In fact, the main soft-tissues considered are usually collateral ligaments, cruciate ligaments, and the knee capsule.

As it is the first reported case of such a kind of sensitivity study, this paper presents some limitations based upon different assumptions formulated during the development of the native knee model and the planning of the sensitivity analysis. Only one specimen has been analysed and only one motor task has been simulated up to 60° of flexion, even if the results were independent by the knee flexion. Ligaments have been model as single bundles and only linear model have been inspected for all the materials omitting poro-elastic solutions. In particular, in order to better research the impact of the modelling cartilage, a non-constant thickness or a more realistic material models could be considered for further investigations. Additionally, in order of obtaining isotropic characteristics for modelling the menisci, an averaging of the circumferential modulus with the radial and axial moduli was performed. Observed the difference of the reported values in the literature for the different directions, and identified axial and radial as similar, a future work should evaluate the importance of modeling the menisci as transversely isotropic materials.

Even if this study is based on several assumptions, the data outputs can be considered a first guideline for knee models developers. In fact, this study shows how, among the several parameters for the modelling of an intact knee, special care should be addressed in characterizing the cartilage behaviour more than the other soft-tissues, for which average values can be used for, at least, healthy subjects.

The proposed study can be further developed adding other parameters to verify, i.e., the effect of multi-bundles ligaments or more ligaments to replicate the joint capsule. In addition, more complex material models to characterize the menisci, such as transversal isotropic models, could be thought. Moreover, the attachment site of the ligaments could be also varied to investigate its potential influence on ligament tension and, consequently, on knee biomechanics.

Other investigations can be coupled with this sensitivity analysis that is focused on find the best selection of material inputs for knee model with target the analysis of joint biomechanics. For example, the importance of using more complex models, as poro-elastic models, for the cartilage and menisci should more deepener and eventually tested as an added parameter of the sensitivity analysis.

In conclusion, when considering research questions addressed to the investigation of intact knee joint biomechanics, numerical knee models should be used in order to provide data unlikely to be available with any other testing procedure. In developing a subject-specific healthy knee model, average values collected from a meticulous literature review can be used to obtain biomechanical personalized outputs, but special attention should be paid when selecting the material properties of the cartilage.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FNRS (Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique, CDR 19545501) and by FER ULB (Fonds d’Encouragement à la Recherche, FER 2014). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Pianigiani S, Innocenti B. New Developments in Knee Prosthesis Research. Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2015. The use of finite element modeling to improve biomechanical research on knee prosthesis; pp. 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belvedere C, Leardini A, Catani F, Pianigiani S, Innocenti B. In vivo kinematics of knee replacement during daily living activities: Condylar and post-cam contact assessment by three-dimensional fluoroscopy and finite element analyses. J Orthopaedic Res. 2017;35:1396–1403. doi: 10.1002/jor.23405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Innocenti B, Pianigiani S, Ramundo G, Thienpont E. Biomechanical Effects of Different Varus and Valgus Alignments in Medial Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. J of Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2685–2691. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brihault J, Navacchia A, Pianigiani S, Labey L, De Corte R, Pascale V, Innocenti B. All-polyethylene tibial components generate higher stress and micromotions than metal-backed tibial components in total knee arthroplasty. KSSTA Journal. 2016;24:2550–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3630-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Innocenti B, Robledo Yagüe H, Alario Bernabé R, Pianigiani S. Investigation on the effects induced by TKA features on tibio-femoral mechanics. Part I: Femoral component designs. J Mech Med Biol. 2015;15:1540034. doi: 10.1142/S0219519415400345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pianigiani S, Alario Bernabé R, Robledo Yague H, Innocenti B. Investigation on the effects induced by TKA features on tibio-femoral mechanics. Part II: Tibial insert designs. J Mech Med Biol. 2015;15:1540035. doi: 10.1142/S0219519415400357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pianigiani S, Scheys L, Labey L, Pascale W, Innocenti B. Biomechanical analysis of the post-cam mechanism in a TKA: Comparison between conventional and semi-constrained insert designs. Int Biomech. 2015;2:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innocenti B, Pianigiani S, Labey L, Victor J, Bellemans J. Contact forces in several TKA design: A numerical sensitivity analysis. J Biomech. 2011;44:1573–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pianigiani S, Chevalier Y, Labey L, Pascale W, Innocenti B. Tibio-femoral kinematics in different total knee arthroplasty designs during a loaded a squat: A numerical study. J Biomech. 2012;45:2315–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innocenti B, Bilgen OF, Labey L, van Lenthe GH, Vander-Sloten J, Catani F. Load sharing and ligament strains in balanced, overstuffed and understuffed uka. J Arthropl. 2014;29:1491–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Innocenti B, Bellemans J, Catani F. Deviations From Optimal Alignment in TKA: Is There a Biomechanical Difference Between Femoral or Tibial Component Alignment? J Arthrop. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen D, Mann KA, Verdonschot N. Micro-mechanical modeling of the cement-bone interface: the effect of friction, morphology and material properties on response. J Biomech. 2008;41:3158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelle J, Janssen D, VanEijden J, DeWaal Malefijt M, Verdonschot N. Does high-flexion total knee arthroplasty promote early loosening of the femoral component? J Biomech. 2011;29:976–83. doi: 10.1002/jor.21363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galbusera F, Freutel M, Durselen L, D’Aiuto M, Croce D, Villa T, Sansone V, Innocenti B. Material models and properties in the finite element analysis of knee ligaments: a literature review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2014;2:54. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Victor J, Van Doninck D, Labey L, Innocenti B, Parizel PM. How precise can bony landmarks be determined on Ct scan of the knee? The Knee. 2009;16:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paley D. What is alignment and malalignement? In: Thienpont E, editor. Improving accuracy in knee arthroplasty. Jaypee Brothers Medical publishers; London: 2014. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackburne JS, Peel TE. A new method of measuring patelar height. J Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59:241–242. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B2.873986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaPrade RF, Ly TV, Wentorf FA, Engebetsen L. The posterolateral attachement of the knee: A qualitative and quantitative morphologic analysis of the fibular collateral ligament, popliteous tendon, popliteofibular ligament and lateral gastrocnemious tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:854–860. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310062101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaPrade RF, Engebetsen AH, Thuan VL, Johansen S, Wentorf FA, Engebretsen L. The anatomy of the medial part of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:758–764. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Innocenti B, Salandra P, Pascale W, Piangiani S. How accurate and reproducible is the identification of cruciate and collateral ligaments insertions by using MRI? The Knee. 2015;23:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pianigiani S, Croce D, D’Aiuto M, Villa T, Pascale W, Innocenti B. Are MRI images needed for modeling patient-specific knee soft tissues? J Mech Med Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1142/S021951941750049X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adam C, Eckstein F, Milz S, Shulte E, Becker C, Putz R. The distribution of cartilage thickness in the knee-joints of old-aged individuals – measurement by A-mode ultrasound. Clin Biomech. 1998;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(97)85881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buck RJ, Wirth W, Dreher D, Nevitt M, Eckstein F. Frequency and spatial distribution of cartilage thickness change in knee osteoarthritis and its relation to clinical and radiographic covariates - data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2013;21:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo S, Rylander JH, Andriacchi TP. Knee joint kinematics during walking influences the spatial cartilage thickness distribution in the knee. J Biomech. 2011;44:1405–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okafor EC, Uttukar GM, Widmeyer MR, Abebe ES, Collins AT, Taylor DC, Spitzer CE, Moorman CT, Garrett WE, De-Frate LE. The effects of femoral graft placement on cartilage thickness after anterio cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Biomech. 2014;47:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckstein F, Adam C, Sittek H, Becker C, Milz S, Schudle E, Reiser M, Putz R. Non-invasive determination of cartilage thickness throughout joint surfaces using magnetic resonance imaging. J Biomech. 1997;30:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)81146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumahashi N, Tadenuma T, Kuwata S, Fukuba E, Uchio Y. A longitudinal study of the quantitative evaluation of patella cartilage after total knee replacement by delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of cartilage (dgemric) and t2 mapping at 3.0t: preliminary results. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2001;21:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tissakht M, Ahmed AM. Tensile stress-stran characteristic of the human meniscal material. J Biomech. 1995;4:411–422. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00081-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beillas P, Lee SW, Tashman S, Yang KH. Sensitivity of the tibio-femoral response to finite element modeling parameters. Comp Meth Biom and Biom Eng. 2007:209–2011. doi: 10.1080/10255840701283988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendjaballah MZ, Shirazi-Adl A, Zukor DJ. Biomechanics of the human knee joint in compression: reconstruction, mesh generation and finite element analysis. The Knee. 1995;2:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey RE, Zheng L, Aiyangar AK, Harner CD, Zhang X. Subject-specific finite element modeling of the tibiofemoral joint based on CT, magnetic resonance imaging and dynamic stereo-radiography data in vivo. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136 doi: 10.1115/1.4026228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Y, Zhang X, Chen W. Three-dimensional finite element simulation of total knee joint in gait cycle. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica. 2009;22:4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haut Donahue TL, Hull ML, Rashid M, Jacobs C. A finite element model of the human knee joint for the study of tibiofemoral contact. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:273–280. doi: 10.1115/1.1470171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haut Donahue TL, Hull ML, Rashid M, Jacobs CR. How the stiffness of meniscal attachments and meniscal material properties affect tibio-femoral contact pressure computed using a validated finite element model of the human knee joint. J Biomech. 36:19–34. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwon OS, Purevsuren T, Kim K, Park WM, Kwon TK, Kim YH. Influence of bundle diameter and attachment point on kinematic behavior in double bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using computational model. Comp Math Meth in Med. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/948292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mesfar W, Shirazi-Adl A. Biomechanics of changes in ACL and PCL material properties or prestrains in flexion under muscle force-implications in ligament reconstruction. Comput Methods Biome. 2006;9:201–209. doi: 10.1080/10255840600795959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mootanah R, Imhauser CW, Reisse F, Carpanen D, Walker RW, Koff MF, Lenhoff MW, Rozbruch SR, Fragomen AT, Dewan Z, Kirane YM, Cheah K, Dowell JK, Hillstrom HJ. Development and validation of a computational model of the knee joint for the evaluation of surgical treatments for osteoarthritis. Comp Meth Biom and Biom Eng. 2014;13:1502–1517. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2014.899588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pena E, Calvo B, Martìnez MA, Doblaré M. A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the combined behavior of ligaments and menisci in the healthy human knee joint. J Biomech. 2006;39:1686–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramaniraka NA, Saunier P, Siegrist O, Pioletti DP. Biomechanical evaluation of intra-articular and extra-articular procedures in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a finite element analysis. Clin Biomech. 2007;22:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Fan Y, Zhang M. Comparison of stress on knee cartilage during kneeling and standing using finite element models. Med Eng & Phy. 2014;36:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang NH, Canavan PK, Nayeb-Hashemi H, Najafi B, Vaziri A. Protocol for constructing subjectspecific biomechanical models of knee joint. Comp Meth Biomech Biomed Eng. 2010;13:589–603. doi: 10.1080/10255840903389989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler DL, Kay MD, Stouffer DC. Comparison of material properties in fascicle-bone units from human patellar tendon and knee ligaments. J Biomech. 1986;19:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(86)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butler DL, Guan Y, Kay MD, Cummings JF, Feder SM, Levy MS. Location-dependent variations in the material properties of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Biomech. 1992;25:511–518. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90091-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chandrashekar N, Mansouri H, Slauterbeck J, Hashemi J. Sex-based differences in tensile properties of the human anterior cruciate ligament. J Biomech. 2006;39:2943–2950. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noyes FR, Grood ES. The strength of the anterior cruciate ligament in human and Rhesus monkeys. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58:1074–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prietto MP, Bain JR, Stonebrook SN, Settlage RA. Tensile strength of the human posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). Presented at the 34th Annual Meeting; Atlanta, Georgia, Orthopaedic Research Society. 1998; February 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Race A, Amis AA. The mechanical properties of the two bundles of the human posterior cruciate ligament. J Biomech. 1994;27:13–24. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hashemi J, Chandarashekar N, Slauterbeck J. The mechanical properties of the human patellar tendon are correlated to its mass density and are independent of sex. Clin Biomech. 2005;20:645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kazemi M, Dabiri Y, Li LP. Recent advances in computational mechanics of the human knee joint. CMMM. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/718423. doi.org/10.1155/2013/718423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krone R, Schuster P. An investigation on the importance of material anisotropy in finite element modeling of the human femur. SAE Techical Paper. 2006 doi: 10.4271/2006-01-0064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarathi-Kopparti P, Lewis G. Infleunce of three variable on the stresses in a three-dimensional modelof a proximal tibia-tial knee implant construct. Biomed Mat Eng. 2007:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adouni M, Shirazi-Adl A. Evaluation of knee joint muscle forces and tissue stresses-strains during gate in severe OA versus normal subjects. J Orth Res. 2014;32:69–78. doi: 10.1002/jor.22472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shirazi R, Shirazi-Adl A, Hurtig M. Role of cartilage collagen fibrils networks in knee joint biomechanics under compression. J Biomech. 2008;41:3340–3348. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delport HD. Ph.D. thesis. KU Leuven; Belgium: 2013. Collateral ligament strain of the human knee joint. Native and after total knee arthroplasty. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delport H, Labey L, Innocenti B, De Corte R, Vander Sloten J, Bellemans J. Restoration of constitutional alignment in TKA leads to more physiological strains in the collateral ligaments. KSSTA Journal. 2015;23:2159–2169. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2971-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pianigiani S, Labey L, Pascale W, Innocenti B. Knee kinetics and kinematics: What are the effects of TKA malcongurations? KSSTA journal. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3514-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Victor J. Ph.D. thesis. KU Leuven; Belgium: 2009. Doctoral dissertation. A comparative study on the biomechanics of the native human knee joint and total knee arthroplasty. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramsey DK, Wretenberg PF. Biomechanics of the knee: methodological considerations in the in vivo kinematic analysis of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint. Clin Biomech. 1999;14:595–611. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin F, Makhsous M, Chang AH, Hendrixd RW, Zhang L. In vivo and noninvasive six degrees of freedom patellar tracking during voluntary knee movement. Clin Biomech. 2003;18:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pianigiani S, Vander Sloten J, Labey L, Pascale W, Innocenti B. A new graphical method to display data sets representing biomechanical knee behaviour. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics. 2015;2:18. doi: 10.1186/s40634-015-0034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith BW, Green GA. Acute knee injuries: part I. History and physical examination. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:615–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hodgson RJ, O’Connor PJ, Grainger AJ. Tendon and ligament imaging. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1157–1172. doi: 10.1259/bjr/34786470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal - Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research: 2016 update. MLTJ. 2016;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.1.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]