Abstract

We previously conducted transcriptome analysis of a paired specimen of normal and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues and found that mRNA expression of cystatin A (CSTA), a member of the cystatin superfamily, was perturbed in tumors compared with that in the background mucosa. However, little is known about the significance of CSTA expression in ESCC.

The mRNA expression of CSTA was evaluated by qRT-PCR using 28 paired frozen samples of tumor and nontumor mucosae. The protein expression of CSTA was evaluated by the immunostaining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of ESCC samples from 59 patients who underwent surgery, and its relationship with clinical features was analyzed.

The mRNA expression of CSTA was significantly decreased in ESCC compared with that in matched normal mucosa (P < .0001). The protein expression of CSTA was limited in stratum granulosum and stratum spinosum but not in stratum basal in normal esophageal mucosa. It was reduced in all ESCC tissue samples compared with normal tissues; however, CSTA expression levels in tumors showed considerable variation. Of the 59 samples, 20 did not express CSTA, whereas 39 clearly expressed it. The expression of CSTA in tumors was significantly associated with pT classification (deeper tumor invasions) (P = .0118) and advanced TNM stages (P = .0497). In CSTA-positive tumor samples, CSTA-expressing cancer cells often expressed Ki67, a proliferation marker, which was in sharp contrast to normal mucosa, where Ki67-expressing cells were limited to the basal layer and did not express CSTA. Furthermore, CSTA expression was observed in all 22 lymph node metastases analyzed.

Relatively high levels of CSTA expression in tumors were correlated with tumor progression and advanced cancer stage, including lymph node metastasis.

Keywords: a cysteine protease inhibitor, cystatin A, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

1. Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality.[1] The 2 main histological types of esophageal cancer include esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma, with ESCC accounting for 80% to 90% of all esophageal cancers.[2] Surgery and combined therapies, such as chemotherapy (CT), radiotherapy (RT), or synchronous chemoradiotherapy (CRT), have significantly developed in the past several years[3–5]; however, the overall 5-year survival rate of ESCC still remains low, ranging from 15% to 25%.[2] To improve the survival rate of ESCC, identifying new diagnostic markers or target molecules is urgently needed.

We investigated the genes whose mRNA expression is perturbed in ESCC because their products may potentially act as prognostic and chemosensitive markers as well as therapeutic targets. Our recent transcriptome analysis using serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) identified CSTA, which encodes an intracellular cysteine protease inhibitor cystatin A (CSTA) and has significantly decreased mRNA expression in ESCC compared with that in matched noncancerous esophageal mucosa.[6] CSTA is a member of the type 1 cysteine protease inhibitors, also referred as stefin A, acid cysteine protease inhibitor, keratolinin, or epidermal SH-protease inhibitor.[7–10] It was originally identified as a component of the cornified cell envelope in the upper skin layers[11] and is suggested to play a role in barrier function targeting dust mite proteases.[12] Recent research has shown that CSTA is dysregulated in several skin cancers, and suppression subtractive hybridization analysis to identify genes that are differentially transcribed in ESCC compared with normal tissue demonstrated that CSTA transcripts were significantly downregulated in cancer tissues.[13] However, its contribution to the malignant properties of ESCC is largely unknown.

In this study, we assessed 59 ESCC cases with detailed clinical information and analyzed the relationships between CSTA expression levels and clinicopathological parameters of patients with ESCC. Although the protein expression of CSTA was generally downregulated in ESCC compared with normal esophageal mucosa, retrospective analyses demonstrated that relatively high levels of CSTA expression in ESCC correlated with tumor progression and advanced stage of cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

We enrolled 59 patients with histologically confirmed ESCC diagnoses. Of these, 46 patients who underwent esophagectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection from January 2013 to August 2015 at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) provided informed consent before sample collection. Quantitative PCR for mRNA expression analysis was performed using 28 paired frozen samples from these patients. This study was approved by the NCGM research ethics committee (121 and 1484). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of surgical specimens from remaining 13 patients who were treated from April 2008 to December 2012 were analyzed by immunohistochemical staining. From these patients, consent was obtained retrospectively in accordance with the NCGM research ethics committee (1622). We retrieved clinicopathological parameters including tumor stage (according to the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 7th edition published by the Union for International Cancer Control) from hospital records.

2.2. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using the RNA isolation reagent RNA-Bee (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX). After treating the RNA with DNase I, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed using ABI TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) as previously described. Threshold cycle numbers were determined using the Sequence Detector software and transformed as described by the manufacturer, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the calibrator gene. The TaqMan Gene expression assay IDs for the genes used in this study are as follows: CSTA, Hs00193257_m1; GAPDH, Hs00266705_g1.

2.3. Immunohistochemical analysis

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of surgical specimens from patients with ESCC were deparaffinized and rehydrated. The antigen was retrieved using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in an autoclave for 30 minutes at 95°C. Sections were stained using an anti-CSTA antibody (HPA001031; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.). Diaminobenzidine staining was performed using the ImmPACT DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin. For double staining of CSTA and Ki67, the MACH 2 Double Stain 1 Kit (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) and Warp Red Chromogen Kit (Biocare Medical) were used to detect anti-Ki67 antibody (MIB-1, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) signals. All slides were reviewed by 2 observers who were blind to clinical and pathological data. On the basis of the proportion of CSTA-positive areas in the malignant tissue, we classified ESCC cases into CSTA-negative (the percentage of CSTA-positive tumor cells was ≤20% on immunostaining) and CSTA-positive groups (the percentage of CSTA-positive tumor cells was >20%). Because there was a clear difference between CSTA-positive/negative, there appeared to be no difficulty judging CSTA-positive/negative. Intraobserver reliability of the CSTA staining results showed no statistically significant differences. The 2 observers exhibited high interobserver reliability.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Each tumor was classified on the basis of the location, size, pathology, lymph node condition, and degree of metastasis (pTNM, 7th edition, 2009). CSTA staining results were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for age and the Fisher exact test for gender, tumor location, pT status, pN status, pM status, and disease stage. Data were expressed as mean ± SD, and results were compared using paired and unpaired Student t tests. Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism 5 statistical program (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). All tests were 2-tailed, and P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. CSTA expression was lower in ESCC than in normal esophageal mucosa

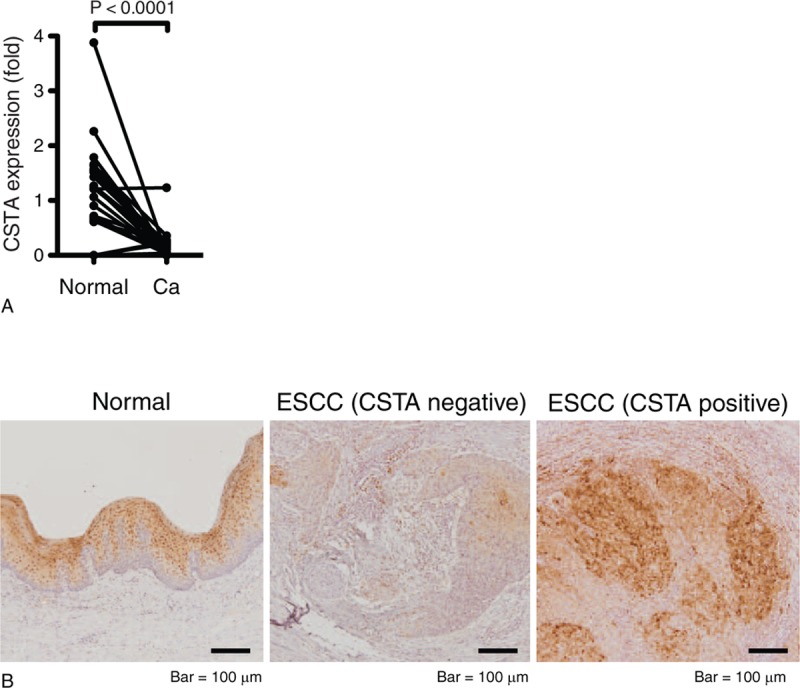

First, regarding CSTA, we validated the results of a previous study[13] and those obtained by SAGE-seq analysis from our study[6] by quantitative RT-PCR using paired normal and ESCC frozen tissue samples. The CSTA mRNA expression was significantly decreased in cancer tissues compared with that in matched normal mucosa (P < .0001, Fig. 1A). Next, we performed immunohistochemical analyses to investigate the protein expression and localization of CSTA in normal esophageal mucosa and ESCC. In normal mucosa, CSTA was detected in all the mucosal layers except a monolayer of stratum basale. All normal tissue samples were CSTA-positive, and there was no difference in the staining pattern. Contrastingly, CSTA expression was reduced in all ESCC tissue samples compared with that in normal tissues; the number of CSTA-negative cells was more in ESCC tissue samples than in normal mucosae. In some malignant tissues, the expression of CSTA was focal and not all tumor cells expressed CSTA. However, the frequency of CSTA-positive cells in the tumors showed considerable variation (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

CSTA expression was decreased in ESCC compared with normal esophageal mucosa. (A) CSTA transcript levels determined by RT-PCR in paired samples from 28 patients with ESCC. Data indicate expression relative to the mean levels of normal tissues. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of CSTA expression in noncancerous tissue and ESCC specimens. Representative staining of CSTA-negative (≤20% of the tumor cells are CSTA-positive) or CSTA-positive (>20% of the tumor cells are CSTA-positive) samples.

3.2. Correlations between CSTA immunoreactivity and ESCC clinicopathological features

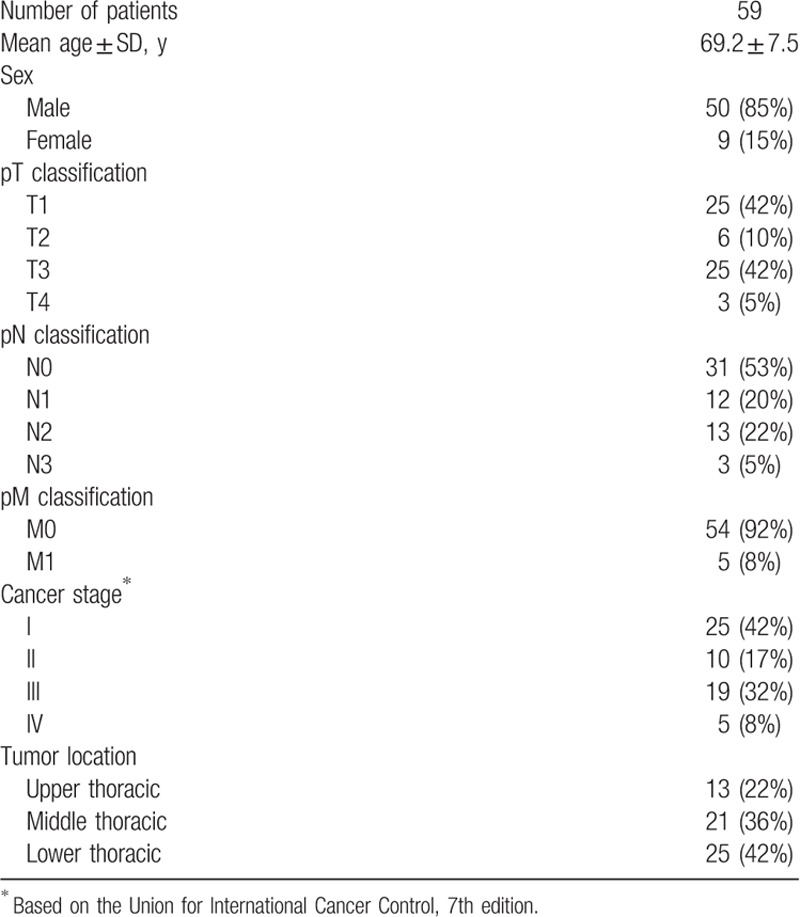

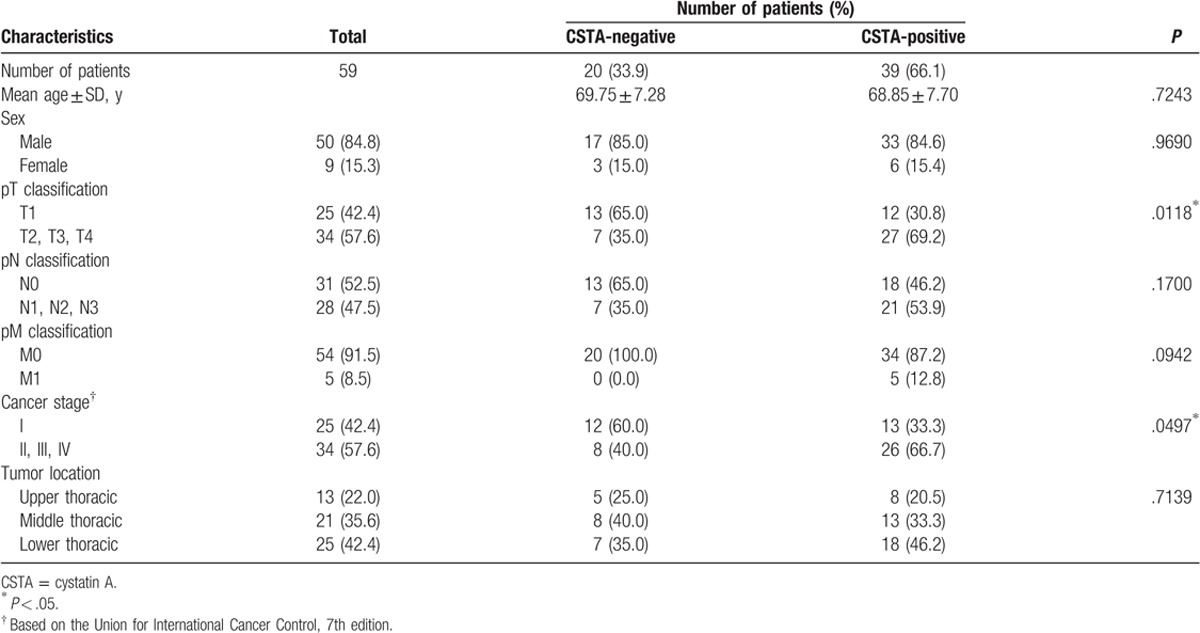

On the basis of the proportion of CSTA-positive area in the malignant tissue, we classified the ESCC cases into CSTA-negative (the percentage of CSTA-positive tumor cells was ≤20% on immunostaining) and CSTA-positive groups (the percentage of CSTA-positive tumor cells was >20%) and analyzed the relationships between CSTA expression and clinicopathological features of ESCC tumors. The demographic features of the 59 ESCC patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of these patients was 69.2 years, and most patients were males (84.8%). Univariate analysis revealed no difference between the CSTA-negative and CSTA-positive groups with respect to gender, age, tumor location, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis. Because the CSTA expression levels were decreased in ESCC, we hypothesized that this reduced CSTA expression was related to advanced tumor stages; however, we found that higher CSTA expression in tumors (CSTA-positive group) was significantly associated with advanced pT (P = .0118) and TNM (P = .0497) stages (Table 2). Because CSTA expression was significantly correlated with tumor invasion, we performed double staining for CSTA and Ki67, which is expressed only in proliferating cells. In the CSTA-positive group, Ki67 was often expressed in cells that were CSTA-positive, which was in sharp contrast to normal mucosa, where proliferating cells that expressed Ki67 were limited to the basal layer and did not express CSTA (Fig. 2A). Further, we examined CSTA expression in lymph node metastases because cases with CSTA-positive tumors tended to be associated with lymph node metastases, although this association was not statistically significant (P = .1700) (Table 2). Consistent with this result, CSTA expression was observed in all 22 lymph node metastases that we analyzed (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological features of CSTA-positive or CSTA-negative ESCC.

Figure 2.

High CSTA expression in proliferative ESCC and lymph node metastases. (A) Representative images produced from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples of ESCC and adjacent noncancerous, normal mucosa, which were double-stained with anti-CSTA (dark brown) and anti-Ki67 (pink) antibodies. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of CSTA expression in lymph node metastases of ESCC.

4. Discussion

We previously conducted transcriptome analysis using paired specimens from resected ESCC tissues and found that CSTA, a cysteine protease inhibitor, has altered expression in ESCC.[6] In this study, we demonstrated that the frequency of CSTA-positive cells in tumor tissues was less than that in adjacent normal mucosae; however, portions of the tumors showed high CSTA expression levels, and the relatively higher CSTA expression in tumors correlated with advanced tumor invasion and cancer stage.

Invasion to the surrounding tissue and degeneration of the basement membrane are the most important features of cancer progression and metastasis. As CSTA is a potential inhibitor of cysteine protease, decreased expression and consequent loss of the inhibitory activity of CSTA were expected to increase the cancer-related proteolytic activity. However, our finding that a relatively higher expression of CSTA in ESCC is associated with advanced tumor progression is contradictory to the hypothesized tumor suppressor role of CSTA. Recent studies demonstrating the correlation of high CSTA levels with tumor progression and poor prognosis may support our observation. One such study, including the immunohistochemical analysis of 384 breast tumors, demonstrated that the survival rate of patients with CSTA-positive tumors was significantly lower than those with CSTA-negative breast tumors.[14] Another study assessing the levels of cysteine protease inhibitors using ELISA in 345 patients with colorectal cancers revealed that increased levels of cysteine protease inhibitors were associated with advanced Duke stage.[15] The upregulation of CSTA in lung cancer was also reported.[16] Thus, it has been proposed that CSTA has alternative functions besides protease inactivation, which can contribute to more advanced tumor features. In human keratinocytes, knockdown of CSTA led to decreased cell–cell adhesion by disrupting the desmosomal structures.[17] Recently, we reported that a relatively higher expression of periplakin (PPL), a desmosome protein,[18,19] in ESCC correlated with advanced tumor size, lymph node metastasis, advanced tumor stage, and poor prognosis.[20] We also observed that PPL expression facilitated tumor cell growth in vivo, probably due to PPL-promoted cell–cell adhesion. ESCC cells with forced expression of PPL often piled up and formed stratified layers, whereas mock-transfected cells formed a monolayer sheet.[21] This mechanism may explain why relatively higher CSTA expression in tumors is correlated with tumor progression and advanced cancer stage. A low CSTA expression and destabilization of the desmosomal structures may limit tumor growth in the normal squamous cell mucosa, which has tight cell–cell adhesion, resulting in a propensity toward an intramucosal type of cancer. In contrast, CSTA-positive cancer cells may not lose their differentiating features, such as the desmosomes, which could promote penetration between squamous cells and further into the submucosal layers. A crosstalk between CSTA and desmosomal proteins, including PPL, will be the subject of future studies.

In this study, we observed that some CSTA-positive cancerous cells also expressed Ki67, a proliferation marker, in ESCC tissues, which has never been observed in normal mucosa. This indicates that CSTA expression in ESCC is uncontrolled and may contribute to tumor malignancy. It has been reported that CSTA displays anti-apoptotic activity through its inhibition of UVB-induced caspase 3 activation in human keratinocytes.[22] A previous report that forced expression of CSTA in tumor cells attenuated cathepsin activity and TNF-induced apoptosis[23] may also suggest that CSTA expression in ESCC counters the activation of apoptosis. It has been demonstrated that smoking influences CSTA expression in the lungs.[16] Although smoking is one of major risk factors for ESCC, we have not analyzed whether smoking affects the expression of CSTA in ESCC tissues. Further studies, including these analyses, and the elucidation of biological roles of CSTA in established cancer cells will refine the value of CSTA detection as a clinical marker for ESCC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Yasuko Nozaki for her technical assistance. We would like to thank Enago for the English language review.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yuki I. Kawamura.

Data curation: Daiki Shiba, Masayoshi Terayama, Kazuhiko Yamada, Taeko Dohi, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Formal analysis: Daiki Shiba, Masayoshi Terayama, Kazuhiko Yamada, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Funding acquisition: Kazuhiko Yamada, Taeko Dohi, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Investigation: Daiki Shiba, Masayoshi Terayama, Kazuhiko Yamada, Teruki Hagiwara, Chinatsu Oyama, Miwa Tamura-Nakano, Toru Igari, Chizu Yokoi, Daisuke Soma, Kyoko Nohara, Satoshi Yamashita, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Project administration: Yuki I. Kawamura.

Resources: Kazuhiko Yamada, Toru Igari, Chizu Yokoi, Daisuke Soma, Kyoko Nohara, Satoshi Yamashita.

Supervision: Kazuhiko Yamada, Toru Igari, Taeko Dohi.

Validation: Kazuhiko Yamada, Toru Igari, Taeko Dohi, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Writing – original draft: Daiki Shiba, Masayoshi Terayama, Taeko Dohi, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Writing – review & editing: Daiki Shiba, Masayoshi Terayama, Kazuhiko Yamada, Teruki Hagiwara, Chinatsu Oyama, Miwa Tamura-Nakano, Toru Igari, Chizu Yokoi, Daisuke Soma, Kyoko Nohara, Satoshi Yamashita, Taeko Dohi, Yuki I. Kawamura.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRT = chemoradiotherapy, CSTA = cystatin A, CT = chemotherapy, ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, PPL = periplakin, RT = radiotherapy, SAGE = serial analysis of gene expression.

Funding/support: This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants Numbers JP15K10124, JP15H04503, JP16K09299, and by grants from the NCGM (26–110, 26–117, 27–1406, 29–1008, 29–1013, 29–1019, and 29–1029).

All authors have no financial or other relations that could lead to a conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, et al. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013;381:400–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Van Meerten E, Van der Gaast A. Systemic treatment for oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2005;41:664–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cohen DJ, Leichman L. Controversies in the treatment of local and locally advanced gastric and esophageal cancers. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1754–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gwynne S, Falk S, Gollins S, et al. Oesophageal chemoradiotherapy in the UK—current practice and future directions. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:368–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Otsuo T, Yamada K, Hagiwara T, et al. DNA hypermethylation and silencing of PITX1 correlated with advanced stage and poor postoperative prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:84434–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brown WM, Dziegielewska KM. Friends and relations of the cystatin superfamily-new menbers and their evolution. Protein Sci 1997;6:5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dubin G. Proteinaceous cysteine protease inhibitors. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005;62:653–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Magister S, Kos J. Cystatins in immune system. J Cancer 2013;4:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ. Evolution of proteins of the systatin superfamily. J Mol Evol 1990;30:60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Steven AC, Steinert PM. Protein composition of cornified cell envelopes of epidermal leratinocytes. J Cell Sci 1994;107:693–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kato T, Takai K, Mitsuichi K, et al. Cystatin A inhibit IL-8 production by keratinocytes stimulated with Der p 1 and Der f 1: biochemical skin barrier against mite cysteine proteases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zinovyeva MV, Monastyrskaya GS, Kopantzev EP, et al. Identification of some human genes oppositely regulated during esophageal squamous cell carcinoma formation and human embryonic esophagus development. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kuopio T, Kankaanranta A, Jalava P, et al. Cysteine protease inhibitor cystatin A in breast cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:423–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kos J, Krasovec M, Cimerman N, et al. Cysteine proteinase inhibitors stefin A, stefin B, and cystatin C in sera from patients with colorectal cancer: relation to prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Butler MW, Fukui T, Salit J, et al. Modulation of cystatin A expression in human airway epithelium related to genotype, smoking, COPD, and lung cancer. Cancer Res 2011;71:2572–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gupta A, Nitoiu D, Brennan-Crispi D, et al. Cell cycle- and cancer-associated gene networks activated by Dsg2: evidence of cystatin A deregulation and a potential role in cell-cell adhesion. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ruhrberg C, Hajibagheri MA, Parry DA, et al. Periplakin, a novel component of cornified envelopes and desmosomes that belongs to the plakin family and forms complexes with envoplakin. J Cell Biol 1997;139:1835–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sonnenberg A, Liem RK. Plakins in development and disease. Exp Cell Res 2007;313:2189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yamada K, Hagiwara T, Inazuka F, et al. Expression of the desmosome-related molecule periplakin is associated with advanced stage and poor prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res. In press. doi.org/10.21037./tcr.2018.01.03. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Otsubo T, Hagiwara T, Tamura-Nakano M, et al. Aberrant DNA hypermethylation reduces the expression of the desmosome-related molecule periplakin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med 2015;4:415–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Takahashi H, Komatsu N, Ibe M, et al. Cystatin A suppresses ultraviolet B-induced apoptosis of leratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci 2007;46:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Foghsgaard L, Wissing D, Mauch D, et al. Cathepsin B acts as a dominant execution protease in tumor cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J Cell Biol 2001;153:999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]