Abstract

In recent years, regenerative techniques have been increasingly studied and used to treat osteochondral lesions of the talus. In particular, several studies have focused their attention on mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) exhibit morphological characteristics and properties similar to other mesenchymal cells, and are able to differentiate into several cellular lines. Moreover, these cells are also widely available in the subcutaneous tissue, representing 10 - 30% of the normal body weight, with a concentration of 5,000 cells per gram of tissue.

In the presented technique, the first step involves harvesting ADSCs from the abdomen and a process of microfracture and purification; next, the surgical procedure is performed entirely arthroscopically, with less soft tissue dissection, better joint visualization, and a faster recovery compared with standard open procedures. Arthroscopy is characterized by a first phase in which the lesion is identified, isolated, and prepared with microperforations; the second step, performed dry, involves injection of adipose tissue at the level of the lesion.

Between January 2016 and September 2016, four patients underwent arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesion of the talus with microfractured and purified adipose tissue. All patients reported clinical improvement six months after surgery with no reported complications. Functional scores at the latest follow-up are encouraging and confirm that the technique provides reliable pain relief and improvements in patients with osteochondral lesion of the talus.

Keywords: Medicine, Issue 131, Adipose-derived stem cells, osteochondral lesion of the talus, cartilage, regenerative medicine, arthroscopy, ankle, liposuction

Introduction

Arthroscopy is the gold standard for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLTs) with the aim of pain relief, restoring functionality, and improving quality of life, especially in young and active patients.

Currently, arthroscopic techniques can be classified in three ways. The reparative technique stimulates cells derived from bone marrow through a debridement and microperforations at the level of lesion. The reconstructive technique replaces the lesion using an autologous or heterologous ostechondral graft. The regenerative technique exploits the ability of multipotent cells to differentiate and replicate to reconstruct the damaged tissue1,2,3,4,5,6.

In recent years , regenerative techniques have been the subject of numerous in vitro and in vivo studies for the treatment of OLTs, and particularly mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue (ADSCs)7,8,9. These mesenchymal stem cells exhibit morphological and functional characteristics similar to other multipotent cells, isolated from other tissues; they also have the ability to differentiate into several and different cellular lines both in vitro and in vivo10,11,12,13. The focus on research regarding these cells is mainly due to their localization, in fact they represent from 10% to 30% of normal body weight with a concentration of 5,000 cells per gram of tissue13,14. On the other hand, a factor that limits the use of these cells is related to their handling during laboratory procedures. The lipoaspirate containing aggregates of adipocytes, collagen fibers, and normal vascular components is enzymatically processed with collagen A type I, and subjected to hemolysis before culture. The aim here is to describe the protocol for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus using microfractured and purified adipose tissue.

Protocol

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

1. Medical History

Start clinical examination with a detailed patient history. NOTE: An OLT must always be suspected in case of instability of the ankle with repeated sprains associated with swelling, stiffness, pain, and joint blockage. Moreover, in many cases OLT may be associated with a history of systemic disease, such as inflammatory or vascular disease, neuropathy or neurologic disease, and diabetes. The use of drugs or medical issues that may influence healing must be evaluated and taken into account.

2. Clinical Examination

Evaluate the patient in an orthostatic position to highlight ankle or hind-foot deformity. Assess muscle and tendon function and ankle range of movement (ROM). A diffuse tenderness is often present, especially during maximum flexion and extension, and it is not uncommon to encounter a touch-sensitive area at the level of the articular joint.

Perform an anterior and posterior drawer test to identify a concomitant lateral ankle instability.

During the preoperative consultation, record the following clinical and functional scores: American Orthopedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS) ankle and hind-foot scores15, Visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score16, and 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12)17.

3. Radiological Assessment

Perform a bilateral weight bearing radiograph of the foot and ankle. This consists of conventional weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) mortise, and lateral weight-bearing views of the ankle. Perform AP mortise in neutral position, and with 15 degrees of internal rotation for a better visualization of the talus. NOTE: Only 50% of OLT can be diagnosed with radiograph; in case of big lesions, an area of detached bone surrounded by radiolucency can be noted18.

Perform a conventional computed tomography-scan (CT-scan) of the ankle. A CT-scan allows a precise location and size of the lesion, identifying also bone fragments in case of detachment. The weak point of the CT is the ability to show the status of the cartilage. A previous study showed a sensitivity and specificity of 0.81 and 0.99, respectively, for detecting OLTs on CT19,20.

Perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle. MRI is fundamental in cartilage and subchondral bone assessment. Moreover, the MRI does not involve ionizing radiation, and allows a better visualization of soft-tissue. The literature reports a sensitivity and specificity of 96% in detecting OLTs21,22.

4. Surgical Technique

- Harvesting and processing of the adipose tissue

- Prepare Klein solution: 1 L of 9 g/L saline, 50 mL of 1% lidocaine, 1 mL of 1:1000 epinephrine, 10 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate, and 0.1 mL of 10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide.

- Create two para-umbilical incisions of about 0.5 cm with a scalpel blade. Inject approximately 300 mL of Klein solution into the subcutaneous fat tissue of the abdomen through the incisions using 60 mL syringes with a 18G needle (Figure 1).

- Harvest 40 - 45 mL of ADSCs using a 13G blunt cannula attached to a 20-mL syringe and introduced into the processing kit (Figure 2). Typically, perform the harvesting in the peri-umbilical area.

- Insert 100 - 130 mL of lipoaspirate in the closed system. Push the lipoaspirate into the device through a large filter to obtain a first cluster reduction; at the same time, a corresponding quantity of saline solution exits toward the wasting bag. A key role is played by stainless steel marbles to obtain a temporary emulsion between oil, blood, and saline. Remove oil residues and contaminated blood by a gravity counter-flow of saline solution.

- After this washing step (the flowing solution appears clear and the lipoaspirate yellow), stop the saline flux and reverse the device (gray cap up), leading to the second adipose cluster reduction. Obtain the reduction by pushing the floating adipose clusters through the second cutting hexagonal filter, pushing fluid from below with a 10-mL syringe. Collect the final product into a 10-mL syringe connected to the upper opening of the device. NOTE: The processing kit for fat tissue improves standard lipofilling technique: in fact, the system consists of a closed, full-immersion, low-pressure cylindrical system, in order to obtain a fluid and uniform product containing a great number of pericytes. This procedure allows the processing of adipose cells exclusively via mild mechanical forces, and preserving the integrity of the stromal vascular niche. The process is the least traumatic possible, and makes the final product available in a short time (15 - 20 min), without enzymatic treatments or expansion. Undamaged vasculostromal niches help the healing process.

- Once the ADSCs have been harvested, apply a compression bandage on the abdomen.

- Surgical procedure and Adipose Tissue Injection

- Place the patient in a supine position under spinal anesthesia with a tourniquet, at a pressure of 250 mmHg, at the level of the thigh to decrease the bleeding and allow a better arthroscopic visualization1.

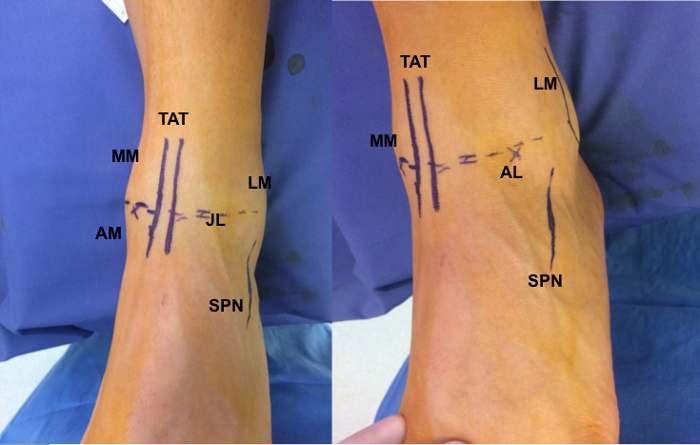

- Mark the anatomical landmarks on the skin with a dermographic pen. Landmarks are essential to avoid iatrogenic injuries. Mark the following (Figure 3): both malleoli (lateral (LM) and medial (MM)) the anterior joint line (JL), identified with dorsi- and plantar-flexion of the ankle joint the tibialis anterior tendon (TAT), and Achilles tendon the great saphenous vein, which runs just ahead of the medial malleolus the superficial peroneal nerve (SPN)

- First, perform the anteromedial portal just medial to the tibialis anterior tendon, coinciding with a soft spot. This portal represents the approach portal. In most cases, a depression with the ankle in dorsiflexion is visible and palpable.

- Cut only the skin with a blade, and then perforate the capsule by blunt dissection. Take care to avoid the saphenous nerve and the great saphenous vein. The saphenous vein is located 9 mm laterally to the portal, while the nerve is about 7.4 mm lateral to the portal. This constitutes one of two primary viewing portals.

- Check the joint line, place the anterolateral portal, medial to the lateral malleolus, and lateral to the extensor digitorum tendon. NOTE: When performing the anterolateral portal, prevent any injuries to the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve (the lateral branch of the superficial peroneal nerve); for this reason, after cutting, the skin must be followed by blunt dissection.

- Inspect the articular cartilage to assess size and position. Evaluate the condition and the quality of the cartilage with the palpator. Osteochondral lesions of the talus are usually located either posteromedially or anterolaterally.

- Perform arthroscopic treatment using wide-angle 2.7-mm arthroscopes with a 30° viewing angle, though some surgeons will use a larger 4 mm arthroscope, and keep the instrument in the anterior recess of the joint. Non-invasive joint distraction techniques and hyper plantar flexion can be used to access most of the talar dome.

- In case of a posterior lesion, percutaneously place a Hintermann spreader to distract the joint and allow exposure of the lesion. The Hintermann spreader has an opening lever arm applied on two K-wires previously positioned in the tibia and talar bone medially or laterally, according to the lesion side. In the case of a lateral lesion, take care to insert the proximal K-wire in the tibial bone, avoiding the fibula, to achieve better distraction of the joint.

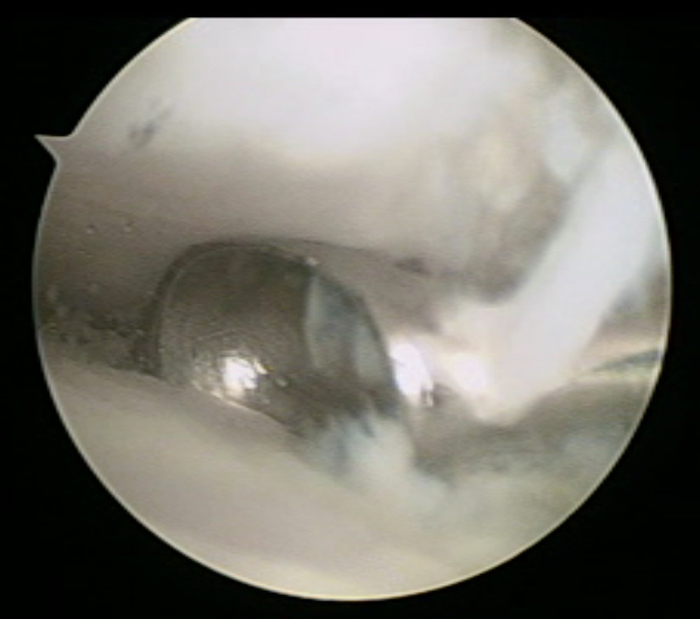

- Prepare the lesion with a curette, removing the damaged and unstable cartilage, the calcified layer and necrotic and sclerotic bone in order to create a regular-shaped contained lesion with shouldered borders. For this step, use a standard arthroscopic curette (Figure 4).

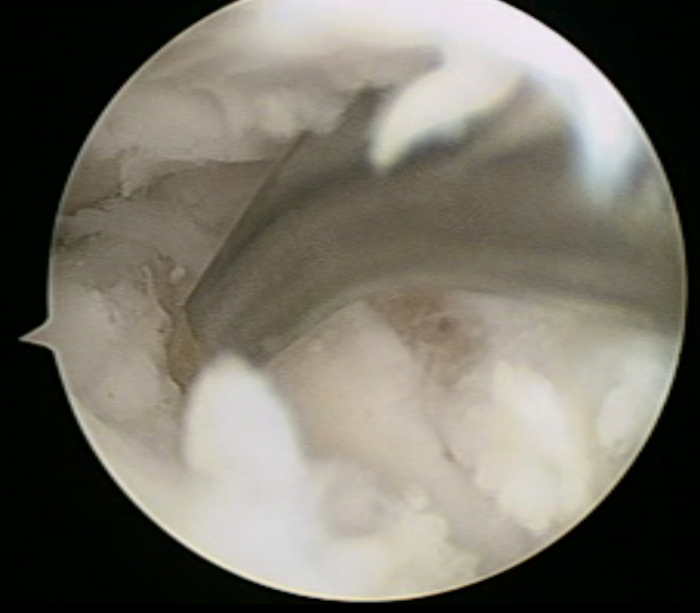

- Stimulate bone marrow stem cells from subchondral bone performing microperforations roundly from the outside to the inside of the lesion.

- Carry out perforations with intervals of about 3 mm between them. Induce microfractures using a Chondral Pick on the healthy subchondral bone underneath the defect (Figure 5). NOTE: A hemorrhage results in the formation of a fibrin clot. Blood clotting products, via inflammatory cascade activation, release vasoactive mediators, growth factors, and cytokines. These factors have the power to stimulate vascular invasion and migration of mesenchymal stem cells into the chondral portion of the lesion. These pluripotent cells are stimulated to differentiate into fibroblasts, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts, and play an important role in the stimulation of repair of the lesion. Paracrine growth factors in the articular environment promote the formation of extracellular matrix and the production of fibrocartilage. At the same time, cells of the bone part of the lesion produce an immature bone tissue that is progressively replaced by a mature bone.

- Remove the intra-articular water using the shaver in aspiration and the remaining liquid using a cotton sponge until the joint is completely dry.

- Adipose-derived stem cell injection

- Inject 5 - 7 mL of adipose-derived stem cells, previously prepared in Step 4.1.3, into the ankle joint using one of the two portals (anteromedial or anterolateral).

- Release the tourniquet.

5. Postoperative Care

Avoid ankle movements for 15 days, with the operated limb in full discharge.

15 days after surgery, allow active and passive movements of the ankle, until full recovery and range of motion is reached.

Allow charge 30 days after surgery.

6. Clinical and Radiographic Follow-Up

Representative Results

Between January 2016 and September 2016, four patients underwent arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesion of the talus with microfractured and purified adipose tissue. All patients reported clinical improvement six months after surgery. Preliminary clinical results are reported in Table 1. No complications were reported.

In recent years, the use of ADSCs for the treatment of foot and ankle pathologies has increased. In 2013, Kim et al.23 treated 65 elderly patients, older than 50 years for symptomatic OLT dividing for the type of treatment: – isolated marrow stimulation – marrow stimulation in association with ADSCs

At final follow-up, patients with a combined treatment showed significant clinical improvement compared to the isolated marrow stimulation treatment. A subsequent study, conducted by the same group24, for the treatment of OLT, confirmed how the combined treatment of SVF and marrow stimulation was superior to isolated microfracture.

In 2016, Kim et al.25 assessed the outcomes in 49 patients treated with marrow stimulation and lateral sliding calcaneal osteotomy. Twenty-six patients also underwent MSC injection. One year after surgery, patients treated with MSC reported a higher ICRS score and clinical outcomes. Recently, Kim et al.26 noted that patients treated with MSC injection after supramalleolar osteotomy and marrow stimulation reported higher clinical and radiological outcomes, compared to patients treated without MSC.

Figure 1: Saline solution containing adrenaline and lidocaine is injected at the level of the abdomen using a 20 g cannula. For liposuction, use a 13 g cannula connected to a syringe. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: The processing kit for fat tissue consists of a single-use kit for the lipoaspiration and purification of adipose tissue. All procedures are performed with the ADSCs immersed in a saline solution, avoiding any trauma and maintaining intact the vasculostromal niches containing mesenchymal stem cells and pericytes. The unit consists of a transparent plastic cylinder with filters and beads for the microfracturing of adipose tissue. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Outside views of ankle during surgical planning. With the patient in the supine position, it is useful to identify all the landmarks on the joint needed for the surgical procedure. AM = anteromedial portal AL = anterolateral portal MM = medial malleolus LM = lateral malleolus TAT = tibalis anterior tendon JL = joint line SPN = superficial peroneal nerve Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Arthroscopic view. The lesion is prepared using a curette removing the damaged cartilage and the necrotic and sclerotic bone Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Arthroscopic view. Microfractures, performed at the level of the osteochondral lesion, stimulate bleeding and leakage of mesenchymal stem cells from the subchondral bone. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Patients | Pre-operative | 6 months after surgery | ||||

| AOFAS | VAS | SF-12 | AOFAS | VAS | ||

| PCS | MCS | |||||

| 1 | 44 | 8 | 31.1 | 32.4 | 88 | 3 |

| 2 | 32 | 7 | 27.5 | 42.1 | 78 | 2 |

| 3 | 52 | 9 | 40.1 | 28.7 | 87 | 2 |

| 4 | 59 | 8 | 36.6 | 41 | 82 | 2 |

| Mean | 46.75 | 8 | 33.83 | 36.05 | 83.75 | 2.25 |

Table 1: Clinical results at 6 months of follow-up. AOFAS: The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society Score; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale for Pain; SF-12: 12-Item Short Form Survey; MCS: Mental Component Score; PCS: Physical Component Score.

Discussion

In recent years, clinical and preclinical trials have focused their attention on the effect of ADSCs to treat different musculoskeletal pathologies. The aim of this article is to describe the protocol for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus using microfractured and purified adipose tissue in association with arthroscopic microperforations. The protocol involves several critical steps with high risks of complications. During fat harvesting, complications can be divided into local or systemic complications.

The most common postoperative complication is contour irregularities, with an incidence of 2.7%. This can be avoided using small cannulas, not performing superficial liposuction, and turning the suction off when exiting incisions. Rarely, skin conditions such as hyperpigmentation, necrosis, and erythema in patients with underlying connective tissue disease can be seen27,28. Seromas are often the result of aggressive liposuction due to the collection of serous fluid in a treated area leading to the formation of a single cavity; this is most common in patients with high BMI29. Infection is a very rare complication (<1%) and this may be because of a combination of sterile technique, small incisions, and the antibacterial effects of lidocaine30.

The literature reports subsequent life-threatening complications after liposuction, such as pulmonary embolism, fat embolism, sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and perforation of abdominal organs. The most common cause of death is pulmonary thromboembolism. These complications are due to lack of sterility, poor patient compliance, and permissive post-operative discharge30.

Also during arthroscopy, there are critical steps that can lead to complications: in this protocol, all arthroscopic procedures are performed using an anteromedial and anterolateral portal31. The most frequent complication with this approach is a deficit of the superficial peroneal nerve, reported in 1.04% of patients, despite preoperative marking of the nerve and its branches32,33. Furthermore, the risk increases considering variations of this nerve: anatomical studies have demonstrated that 50% of the population present two branches, and these can reach up to 5 branches with an extremely variable width (1 to 13 mm).

The technique described in the protocol combines the effect of the microfracture in association with mesenchymal stem cells harvested from fat tissue. Microperforations stimulate the development of a reparative tissue: drilling the subchondral bone produces bleeding and leakage of mesenchymal cells, to produce fibrocartilage. The success of microfractures is strictly related to the size of the lesion. If lesions are less than 1.5 cm2, the neo-formed fibrocartilage tissue, although qualitatively different from hyaline cartilage and with lower mechanical properties, can provide adequate reparation, with resolution of the symptoms in a high percentage of cases34,35. ADSCs may form neo-tissue with a hyaline cartilage phenotype, if cultured in association with different growth factors (TGFb, GH, and FGF-2) and placed in a scaffold of fibrin glue36.

The described technique preserves the identity of the pericyte, leaving intact the stromal vascular niche, promoting osteochondral healing in this way. Moreover, ADSCs produce a variety of paracrine bioactive molecules and can activate the physiological healing process. The final product is available in less than 20 min, thanks to the gentle mechanical method. Finally, in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration, ADSCs are minimally manipulated.

The use of MSCs is constantly increasing, and future research should focus on the use of allogeneic ADSCs as described by Lee37. The advantages of an allotransplant would be numerous. First of all, handling and standardization of the product would be easier. Liposuction and processing steps could be eliminated, and a healthy donor could be pre-selected, according to his cytokine and cell marker expression profile, improving the effect of MSCs38.

Disclosures

Federico Giuseppe Usuelli, MD, reports personal fees from Integra and Geistlich, and grants and personal fees from Zimmer, outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

The procedures are performed using the Lipogems System.

References

- D'Ambrosi R, Maccario C, Serra N, Liuni F, Usuelli FG. Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus and Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis: Is Age a Negative Predictor Outcome? Arthroscopy. 2017;33(2):428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher C, et al. T2-mapping at 3 T after microfracture in the treatment of osteochondral defects of the talus at an average follow-up of 8 years. Knee Surg. SportsTraumatol. Arthrosc. 2015;23(8):2406–2412. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polat G, et al. Long-term results of microfracture in the treatment of talus osteochondral lesions. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1299–1303. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-3990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen CJ, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral defects of the talus: outcomes at eight to twenty years of follow-up. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2013;95(6):519–525. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eekeren IC, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic debridement and bone marrow stimulation of osteochondral talar defects: a 5- to 24-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(4):1311–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-3992-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosi R, Maccario C, Ursino C, Serra N, Usuelli FG. Combining Microfractures, Autologous Bone Graft, and Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis for the Treatment of Juvenile Osteochondral Talar Lesions. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(5):485–495. doi: 10.1177/1071100716687367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuelli FG, D'Ambrosi R, Maccario C, Indino C, Manzi L, Maffulli N. Adipose-derived stem cells in orthopaedic pathologies. British Medical Bulletin. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim YS, et al. Assessment of clinical and MRI outcomes after mesenchymal stem cell implantation in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a prospective study. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2016;24(2):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon SK, Kim YS, Yeo JE. Clinical results and second-look arthroscopic findings after treatment with adipose-derived stem cells for knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1308–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk PA, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13(12):4279–4295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taléns-Visconti R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue: Differentiation into hepatic lineage. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2007;21(2):324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timper K, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into insulin, somatostatin, and glucagon expressing cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;341(4):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremolada C, Palmieri G, Ricordi C. Adipocyte transplantation and stem cells: plastic surgery meets regenerative medicine. Cell. Transplant. 2010;19(10):1217–1223. doi: 10.3727/096368910X507187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramaris NC, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in bone healing. Curr. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 2012;7(4):293–301. doi: 10.2174/157488812800793081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigheb M, et al. Italian translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society's (AOFAS) ankle-hindfoot scale. Acta Biomed. 2016;87(1):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–S252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen CJ, Gerards RM, Opdam KT, Terra MP, Kerkhoffs GM. Diagnosing, planning and evaluating osteochondral ankle defects with imaging modalities. World. J. Orthop. 2015;6(11):944–953. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i11.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk CN, Reilingh ML, Zengerink M, van Bergen CJ. Osteochondral defects in the ankle: why painful? Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010;18(5):570–580. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1064-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madry H, van Dijk CN, Mueller-Gerbl M. The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010;18(4):419–433. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz DN, Tashjian GS, Connell DA, Deland JT, O'Malley M, Potter HG. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: a new magnetic resonance grading system with arthroscopic correlation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):353–359. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leumann A, et al. A novel imaging method for osteochondral lesions of the talus--comparison of SPECT-CT with MRI. Am. J. Sports Med. 2011;39(5):1095–1101. doi: 10.1177/0363546510392709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Park EH, Kim YC, Koh YG. Clinical outcomes of mesenchymal stem cell injection with arthroscopic treatment in older patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1090–1099. doi: 10.1177/0363546513479018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Lee HJ, Choi YJ, Kim YI, Koh YG. Does an injection of a stromal vascular fraction containing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells influence the outcomes of marrow stimulation in osteochondral lesions of the talus? A clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2424–2434. doi: 10.1177/0363546514541778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Koh YG. Injection of Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Supplementary Strategy of Marrow Stimulation Improves Cartilage Regeneration After Lateral Sliding Calcaneal Osteotomy for Varus Ankle Osteoarthritis: Clinical and Second-Look Arthroscopic Results. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(5):878–889. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Lee M, Koh YG. Additional mesenchymal stem cell injection improves the outcomes of marrow stimulation combined with supramalleolar osteotomy in varus ankle osteoarthritis: short-term clinical results with second-look arthroscopic evaluation. J. Exp. Orthop. 2016;3(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s40634-016-0048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke CW, Bernstein G, Bullock S. Safety of tumescent liposuction in 15,336 patients. National survey results. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(5):459–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illouz YG. Complications of liposuction. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(1):129–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit VV, Wagh MS. Unfavourable outcomes of liposuction and their management. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46(2):377–392. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.118617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnhardt M, Homann HH, Daigeler A, Hauser J, Palka P, Steinau HU. Major and lethal complications of liposuction: review of 72 cases in Germany between 1998 and 2002. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(6):396e–403e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318170817a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuelli FG, de Girolamo L, Grassi M, D'Ambrosi R, Montrasio UA, Boga M. All-Arthroscopic Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis for the Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(3):e255–e259. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson DC, Roukis TS. Safety of ankle arthroscopy for the treatment of anterolateral soft-tissue impingement. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzangar M, Rosenfeld P. Ankle arthroscopy: is preoperative marking of the superficial peroneal nerve important? J. Foot. Ankle Surg. 2012;51(2):179–181. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeutler MJ, et al. Current Concepts Review Update: Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(3):331–342. doi: 10.1177/1071100716677746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looze CA, et al. Evaluation and Management of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus. Cartilage. 2017;8(1):19–30. doi: 10.1177/1947603516670708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoo JL, et al. Healing full-thickness cartilage defects using adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(7):1615–1621. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Kim W, Lim C, Chung SG. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylosis by Using Allogeneic Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Pilot Study. Stem Cells. 2015;33(10):2995–3005. doi: 10.1002/stem.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feisst V, Meidinger S, Locke MB. From bench to bedside: use of human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Cloning. 2015;8:149–162. doi: 10.2147/SCCAA.S64373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]