Abstract

Sexual minority youth experience elevated rates of internalizing disorders; it is therefore important to identify protective factors that decrease risk for psychological distress in this population. This study examined whether involvement in a romantic relationship, a well-established protective factor for mental health among heterosexual adults, is also protective for young sexual minorities. Using eight waves of data provided by a community sample of 248 racially diverse sexual minority youth (ages 16 – 20 years at baseline), we assessed within-person associations between relationship involvement and psychological distress. Results from multilevel structural equation models indicated that, overall, participants reported less psychological distress at waves when they were in a relationship than when they were not. However, findings differed based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. Specifically, although relationship involvement predicted lower psychological distress for Black and gay/lesbian participants, the association was not present for White participants and, for bisexuals, relationship involvement predicted higher distress. In addition, relationship involvement reduced the negative association between victimization based on sexual minority status and psychological distress, suggesting a stress buffering effect that did not differ based on demographic factors. Together, these findings suggest that being in a romantic relationship may promote mental health for many, but not all, young sexual minorities, highlighting the importance of attending to differences among subgroups of sexual minorities in research, theory, and efforts to reduce mental health disparities.

Keywords: LGBT, psychological distress, romantic involvement, sexual minorities

A large body of research indicates that sexual minority youth (i.e., non-heterosexual adolescents and young adults, most of whom identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual; LGB) experience higher rates of internalizing psychopathology than do heterosexual youth (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Marshal et al., 2011). These mental health disparities are generally viewed as resulting from the chronic stress associated with living in a society that stigmatizes non-heterosexual identities and same-sex attractions (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). It is therefore important to identify factors that are associated with positive mental health among young sexual minorities and that may buffer them from the negative psychological effects of stressors they face due to their sexual orientation (Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011). Among heterosexual adults, one well-established protective factor for mental health is marriage (Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005; Waite & Gallagher, 2000). However, it is not clear if sexual minorities, particularly youth, also experience a mental health benefit from their romantic relationships. The few studies that have investigated associations between romantic involvement and psychological health in youth in general or in sexual minorities are generally limited by cross-sectional designs and inconsistent findings, some of which even suggest negative effects of relationship involvement on mental health.

In the current study, we examined whether romantic relationship involvement may influence the psychological health of sexual minority adolescents and young adults. Using multiwave longitudinal data provided by a diverse sample of LGBT youth, we assessed whether relationship involvement had direct effects on psychological distress and if it buffered the youth from negative psychological effects of sexual minority-specific victimization. Further, we assessed whether any direct or buffering effects of relationship involvement on psychological distress differed by age, gender, race, or sexual orientation (gay/lesbian vs. bisexual).

Relationship Involvement and Mental Health Among Heterosexual Adults

A large body of literature on heterosexual adults has documented the mental health benefits of marriage, which is associated with reduced risk for a wide range of psychological problems (reviewed by Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Married adults, and to a lesser extent those in non-marital committed partnerships, have shown better psychological wellbeing than their single counterparts in samples from nearly two dozen countries (Vanassche, Swicegood, & Matthijs, 2013); these differences tend to persist even when the quality of the romantic relationship is controlled (e.g., Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005; Ross, 1995). Although the selection of psychologically healthy individuals into relationships may account for some of these effects, longitudinal studies have consistently indicated that entry into marriage or another type of committed relationship is followed by improved emotional wellbeing and reduced depression (Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005; Lamb, Lee, & DeMaris, 2003). This suggests that relationship involvement actively confers benefits on mental health. Several theoretical perspectives, mostly focused on marriage (rather than other romantic relationships), have been put forth to explain these findings.

First, social control theories (Umberson, 1987) emphasize how spouses monitor one another’s behavior, encouraging healthy behaviors that promote emotional wellbeing (e.g., good eating habits, exercise), and discouraging unhealthy ones (e.g., heavy drinking; Lewis & Butterfield, 2007). The internalization of behavioral norms for the social role of a spouse may also reduce unhealthy behaviors that are more acceptable for singles (e.g., substance use, casual sex; Umberson, 1987). Second, marriage is associated with tangible legal and financial benefits that promote general health and wellbeing (e.g., spousal income and health insurance; Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Third, according to the social integration perspective, marriage may promote mental health by providing an intimate, emotionally fulfilling, and supportive relationship that satisfies individuals’ needs for social connection (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). Indeed, marriage increases the availability of social support, which is associated with lower psychological distress and depressive symptoms (reviewed by Turner & Brown, 2010). Finally, stress buffering models posit that the social support provided by marriage benefits spouses’ wellbeing by protecting them from the detrimental effects of stressors (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Research has supported this model in married heterosexual couples, indicating that spousal support reduces the negative effects of a wide range of stressors on mental health (Jackson, 1992; Syrotuik & D’Arcy, 1984).

Relationship Involvement and Mental Health among Adolescents and Young Adults

It remains unclear whether the well-documented “marriage benefit” to mental health generalizes to the dating relationships of young people. There are several theoretical reasons why it may not. First, according to socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1992), individuals tend to have many interaction partners during adolescence and young adulthood but restrict social contact to fewer individuals, often spouses, as they age. As a result, being single may not entail the lower levels of social interaction and support for youth that it generally does for adults. Secondly, young dating partners may not exert social control over each other’s behavior in the way that adult spouses do. Because most youth do not live with their romantic partners, they may be less able to monitor each other’s behavior. Also, the social norm that marriage entails, “cleaning up one’s act” and doing what your spouse asks you to do (e.g., Umberson, 1987), may not apply when dating partners are young and unmarried. Third, youth generally do not experience the legal and financial benefits of marriage, such as access to each other’s health insurance (Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013). Finally, some theorists have proposed that adolescents lack the emotional maturity and coping resources to handle the intense emotions and other challenges inherent in intimate relationships, so that romantic involvement may actually put them at risk for psychological distress (Davila, 2008). On the other hand, developing romantic relationship competence represents a central developmental task of adolescence and young adulthood (Erikson, 1950; Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004); therefore, involvement in an intimate relationship may positively influence youth’s mental health by providing them with a sense of accomplishment and social identity (Montgomery, 2005). Young romantic partners may also provide each other a quality of emotional connection not offered by other social partners. It is also possible that dating partners exert some level of social control over one another, reducing engagement in unhealthy behaviors associated with the single “hook-up” culture (e.g., Owen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Fincham, 2010).

Limited research has examined the association between dating relationships and mental health among young people. A national telephone survey of young adults (median age = 23 years) indicated that subjective wellbeing (.e., life satisfaction, happiness, distress, and self-esteem) was higher among those who were dating one person exclusively than among those who were single or dating multiple people (Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005). Similarly, in a community sample of young adults (18–23 years old), romantic involvement was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Simon & Barrett, 2010). Two studies of college students aged 18–25 also found evidence that involvement in dating relationships is associated with better mental health: Compared to single students, those in committed relationships reported fewer depressive symptoms (Whitton, Weitbrecht, Kuryluk, & Bruner, 2013) and fewer academic problems resulting from mental health problems (Braithwaite, Delevi, & Fincham, 2010). However, another study that sampled only first-year college students (predominantly 18 years old) found that involvement in a romantic relationship was not associated with current depressive symptoms, and predicted increases in depression over the following year (Davila, Steinberg, Kachadourian, Cobb, & Fincham, 2004). Although the reason behind these conflicting findings is unclear, it is possible that relationship involvement does not become associated with positive wellbeing until individuals reach young adulthood.

In fact, studies of adolescents younger than 18 years generally indicate that romantic involvement may have a detrimental effect on mental health during this developmental period. Among girls aged 10–13 years, involvement in romantic activities with boys has been associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2004; Davila et al., 2004). Studies of adolescents in middle school and high school (ages 12–17 years) have found that depressive symptoms were higher among frequent daters than infrequent daters (Quatman, Sampson, Robinson, & Watson, 2001) and that depressive symptoms increased more over time in youth who became involved in a different-sex romantic relationship than in those who did not (Joyner & Udry, 2000). Although these associations were present across gender, the longitudinal effect was stronger for girls than for boys (Joyner & Udry, 2000). Interestingly, the two studies yielded conflicting findings regarding whether the effect of relationship involvement on depression differs by age. Joyner and Udry (2000) found that the effect decreased between the ages of 12 and 18 years for girls but not for boys, while Quatman and colleagues (2001) found that the association between frequent dating and depressive symptoms was equally strong in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. It should be noted that links between adolescent romantic involvement and poor mental health are not always observed. For example, La Greca and Harrison (2005) found that teens age 14–19 who were dating had less social anxiety and equivalent depressive symptoms to those who were not dating. Nevertheless, most studies suggest that being involved in romantic relationships prior to age 19 is associated with elevated depressive symptoms, especially for girls.

Relationship Involvement and Mental Health among Sexual Minorities

It also is unclear whether romantic involvement has direct or stress buffering effects on the mental health of sexual minority individuals, particularly youth. In general, the romantic relationships of sexual minority and heterosexual adults are exceedingly similar in terms of relationship quality (e.g., Kurdek, 2005) and levels of social support between partners (Graham & Barnow, 2013), as well as in the associations between relationship functioning and partners’ psychological wellbeing (Whitton & Kuryluk, 2014). This suggests that the “marriage benefit” observed in heterosexual adults is likely to generalize to LGB adults. To the extent that the romantic partnerships of sexual minority adolescents are also similar to those of their heterosexual counterparts, we might expect relationship involvement to be associated with higher depressive symptoms among LGB teens like it is in heterosexual teens. In fact, LGB youth may be especially prone to negative mental health effects of romantic involvement, because dating may heighten the salience of any internal conflicts about sexuality and (if the partner is same-sex) may raise risk for discrimination and conflict with unaccepting family members by revealing their same-sex attractions. Alternately, it is possible that sexual minority youth may benefit more than heterosexual youth do from a romantic partnership, which might provide social support that is lacking from their parents and peers at school (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009).

Of the few studies that have examined associations between relationship involvement and mental health in sexual minorities, most have used adult samples and, because marriage has only recently become available for same-sex partnerships, have examined other forms of committed relationships. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that, compared to single lesbian women, lesbians in a committed relationship report fewer depressive symptoms (Ayala & Coleman, 2000; Kornblith, Green, Casey, & Tiet, 2016; Oetjen & Rothblum, 2000) and better psychological wellbeing (Wayment & Peplau, 1995); similar findings have been observed in gay and bisexual men (Parsons, Starks, DuBois, Grov, & Golub, 2013). Further, in a large probability sample, partnered gay and lesbian adults reported more happiness than single adults of any sexual orientation (but less than married heterosexuals; Wienke & Hill, 2009). However, the one study that has explored whether relationship involvement reduces risk for mental health disorders, assessed by a structured diagnostic interview, found no evidence that it does (Feinstein, Latack, Bhatia, Davila, & Eaton, 2016). There were no differences in rates of anxiety or depressive disorders by relationship status among gay men and lesbian women, and relationship involvement was associated with higher odds of anxiety disorders among bisexual adults.

We could find only three studies on sexual minority youth (Baams, Bos, & Jonas, 2014; Bauermeister et al., 2010; Russell & Consolacion, 2003). One, which focused on same-sex attracted youth in 10th and 11th grade, found that those who dated same-sex partners were no more anxious or depressed than non-daters, but did show higher suicidality (Russell & Consolacion, 2003). The other two found no consistent differences between single and partnered sexual minority youth in psychological wellbeing (Baams et al., 2014; Bauermeister et al., 2010). Together these findings are tentatively suggestive that the negative associations between relationship involvement and mental health commonly found in heterosexual adolescent samples may not generalize to sexual minority youth.

Even less research has examined the potential stress-buffering effects of romantic involvement for sexual minorities. Among adults in same-sex relationships, social support from one’s romantic partner, but not from family or friends, reduced the negative effect of stressful life events on psychological wellbeing (Graham & Barnow, 2013). This suggests that romantic partnerships may play a unique stress-buffering role for sexual minority mental health. In the only study assessing whether romantic involvement per se buffers sexual minorities from minority-specific stressors, Feinstein and colleagues (2016) found that romantic involvement did buffer the effects of discrimination on risk of anxiety or depressive disorders, but only for bisexual adults, not for lesbians or gay men. Clearly, more research is needed on the topic, with consideration to potential differences between subgroups of sexual minorities.

Potential Moderators of Relationship Involvement Effects on Mental Health

As we seek to understand how relationship involvement may affect the mental health of young sexual minorities, we must attend to how its effects may not be uniform across all members of this population. Indeed, theory and findings from existing research suggest that the association between relationship status and mental health may differ along key demographic dimensions, including age, gender, sexual orientation, and race.

As described above, being involved in a marriage or committed romantic relationship is consistently associated with enhanced psychological wellbeing among adult samples of heterosexuals (e.g., Vanassche et al., 2013) and sexual minorities (e.g., Kornblith et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2013); this is generally true even among young adults (aged 18–25; e.g., Simon & Barrett, 2010). In contrast, studies of heterosexual adolescents tend to find that relationship involvement is negatively associated with psychological wellbeing, particularly in early adolescence (e.g., Davila et al., 2004). Therefore, it is possible that the association between relationship involvement and psychological wellbeing among sexual minority youth will be negative in early adolescence but become more positive with increasing age. However, the few existing studies of LGB adolescents suggest that they do not share heterosexual youth’s risk for reduced wellbeing when romantically involved (e.g, Baams et al., 2014; Baumeister et al., 2010) so it is also possible that, among sexual minorities, being in a relationship is beneficial to mental health across adolescence and young adulthood. Determining whether age moderates the association between romantic involvement and wellbeing among sexual minority youth is an important next step for research in this area.

Regarding gender, a large body of data suggests that the psychological benefits of marriage are equal for men and women (e.g., Simon, 2002). Further, the limited existing research suggests that male and female young adults benefit equally from involvement in non-marital different-sex committed relationships (e.g., Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005). However, among adolescents, some longitudinal data suggests that relationship involvement is more detrimental to girls’ than to boys’ wellbeing (Joyner & Udry, 2000). Research to date on sexual minorities has not revealed gender differences in the associations between relationship status and mental health; however, the data are limited and many studies used single-sex samples, precluding tests of moderation by gender. It is important to explore potential gender differences, given key differences in sexual minority men’s and women’s experiences related to their sexual orientation. For example, compared to sexual minority men, sexual minority women experience less frequent sexual orientation victimization (e.g., Herek, 2009; Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008) but higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders (Meyer, 2003).

Specific sexual orientation identities may also influence how romantic involvement affects psychological wellbeing. Compared to gay and lesbian individuals, bisexuals may benefit less from being in a romantic relationship due to unique stressors they face based on their bisexuality (referred to as binegativity; Brewster & Moradi, 2010) that may be heightened upon entry into a relationship. Binegativity, which can be perpetrated by both heterosexuals and lesbian/gay individuals, includes stereotypes that bisexuality is an unstable or illegitimate sexual identity and that bisexuals are sexually irresponsible (e.g., promiscuous, likely to cheat on partners; Brewster & Moradi, 2010). Bisexuals often report experiencing binegativity when involved in committed relationships, including invalidation of their sexual identity by individuals who assume they are lesbian/gay or heterosexual based on their current partner’s gender (Dyar, Feinstein, & London, 2014) and pressure from their non-bisexual partners to change their sexual identity to match the gender pairing of the given relationship (Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014). The only study to date of sexual orientation as a moderator of the association between relationship involvement and mental health (Feinstein et al., 2016) found that, for bisexuals only, romantic involvement increased risk for anxiety disorders but also buffered the negative effects of discrimination on anxiety and depressive disorders. These apparently conflicting findings highlight the necessity of further investigation.

Finally, it is important to assess for racial/ethnic differences in how romantic involvement may influence sexual minority mental health. There is increasing recognition that individuals’ co-occurring social identities (including those related to sexual orientation and race) intersect to influence health (IOM, 2011; Cole, 2009) and that the experiences of sexual minorities can differ by race. Faced with intersecting minority stressors, LGB youth of color may particularly benefit from the social support of a romantic relationship.

The Current Study

The current study aimed to advance our understanding of how relationship involvement influences the psychological wellbeing of young sexual minorities. We used multiwave longitudinal data provided by a large diverse sample of sexual minority youth to assess whether, within-persons, relationship involvement is associated with psychological distress. That is, do sexual minority youth tend to experience less (or more) psychological distress at times when they are in a relationship versus when they are single? In addition, we examined whether relationship involvement may buffer LGB youth from the negative psychological effects of sexual minority-specific victimization. The current multiwave study offered key advantages over the cross-sectional studies that comprise most of the existing literature, which can only speak to between-persons differences (i.e., do currently partnered individuals have less psychological distress than those who are currently single?). Further, the diversity of the sample allowed for examination of potential differences in the direct and buffering effects of relationship involvement by age, gender, sexual orientation, and race.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were drawn from a community sample of 248 sexual minority youth from the Chicago area who participated in a longitudinal study of LGBT youth (Project Q2; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010). This study employed an accelerated longitudinal design in which participants who varied in age at baseline (from 16–20 years) provided eight waves of data over a 5 year period (baseline and approximately 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 42-, 48-, and 60-month follow-up). Baseline data was collected from 2007–2009. Retention at each wave was 85%, 90%, 80%, 82%, 83%, and 82%, respectively. For these analyses, we used data from all time points other than the 18-month follow-up, when relationship status was not assessed. Because identification checks during follow-up waves indicated that 13 participants misreported their age at baseline, any data these participants provided when they were outside the study age range were removed (a total of 22 timepoints).

The majority of participants were cisgender (43.1% cisgender male; 48.8% cisgender female; 8.1% transgender). At baseline, most participants identified as gay (34.3%), lesbian (27.8%), or bisexual (28.2%); 9.7% identified as questioning or unsure. The sample was racially diverse (56.0% Black, 12.1% Latino, 14.1% White, 1.2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1.2% Native American, 11.3% Multiracial, and 4.0% identifying with another racial/ethnic identity).

Assessments were conducted in private rooms at a LGBT community-based health center or a university. At each visit, participants provided informed consent and completed self-report measures of health behaviors, mental health, and psychosocial variables using audio computer-assisted self-interview technology. Participants were paid $25 to $50 at each time point. This study was approved first by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Illinois- Chicago (#2006-0735) and then Northwestern University (STU00047881).

Measures

Demographics

At baseline, a demographic questionnaire assessed participant age, gender (coded cisgender male, transgender, or cisgender female [reference group]), race/ethnicity (coded White, Latino, and Other, with Black as the reference group), and self-reported sexual orientation (coded bisexual and questioning/unsure, with gay or lesbian as the reference group).

All of the following measures were collected at each assessment wave:

Current Relationship Involvement

Participants were asked about their current and recent romantic relationships at each wave. Those who indicated that they were in a current romantic relationship were coded as 1; others were coded as 0.

Psychological Distress

The Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI 18; (Derogatis, 2001), a self-report measure of psychological distress during the previous week, is a widely used psychiatric screening tool in in epidemiological studies and clinical settings, with good reliability and validity (Zabora et al., 2001). Participants report how much they have been distressed or bothered in the last week by each of 18 experiences (e.g., feelings of worthlessness, feeling no interest in things, nervousness or shakiness inside; 0 = Not at all, 4 = Extremely). Scores represent the mean of all items. The BSI was internally consistent across waves (α = .91 to .94).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) victimization

A 10-item measure assessed frequency of ten victimization experiences (e.g., verbal threats, physical assault) “because you are, or were thought to be, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender” during the last 6 months (Never = 0, Three or more times = 3; Newcomb, Heinz, & Mustanski, 2012). Scores represent the mean of all items (α = .77 to .93).

Results

Mplus Version 7 with robust maximum likelihood estimation was used to conduct all analyses (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). A total of 16.2% of data was missing; analyses suggested that data was missing at random (MAR), though not missing completely at random (MCAR). We used full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), which produces unbiased estimates with MAR data (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Level 1 consisted of repeated measures, which were nested within individuals (Level 2). Analyses were conducted using multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM), which treats the repeated measures of within-person variables as indicators of individual level latent variables while adjusting for their non-independence (Lüdtke et al., 2008). To reduce convergence issues from inclusion of variables with dramatically different scales in the same analysis, age was standardized prior to analyses. Effect sizes were estimated using Pseudo R2 values, which represent the proportion of variance in the outcome variable explained by the given predictor. These were calculated by dividing the outcome’s residual variance in a model with a predictor by its residual variance in a model excluding the predictor for models not including interactions (Snijders & Bosker, 1994) and, for models including interactions, by dividing the proportion of variance explained by each effect (main effects, interaction) by the outcome's total variance (Maslowsky, Jager, & Hemken, 2015).

Table 1 includes within and between level correlations, intra-class correlations (ICCs), and means and variances for variables with within-person level variance (i.e., repeated measures). ICCs estimate the proportion of variance attributable to differences between participants; differences within individuals across waves are estimated by 1- the ICC. These indicated considerable within-person variability over time in key variables, including relationship involvement (81%), psychological distress (56%), and LGBT victimization (61%), allowing for tests of within-person associations among them.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Major Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship Involvement | - | −.04 | −.10 | −.09 |

| 2. Psychological Distress | −.05* | - | .44** | .04 |

| 3. LGBT Victimization | −.04 | .21** | - | .02 |

| 4. Age | .06* | −.27** | −.18** | - |

|

| ||||

| ICC | .19 | .44 | .39 | .26 |

| Mean | .52 | .67 | .01 | 21.04 |

| Within Variance | .20 | .28 | .03 | 4.16 |

| Between Variance | .05 | .22 | .02 | 1.49 |

Note. Between level correlations are presented above the diagonal and correlations at the within level are presented below the diagonal.

p < .05;

p < .01.

ICC = intra-class correlation.

Tests of Direct Effects of Relationship Involvement on Psychological Distress

First, to test our primary hypothesis, we ran a model in which psychological distress at each time point was predicted by relationship involvement at that time point. Age at each time point was also included at Level 1, and age, gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity were included at Level 2 in this and all subsequent analyses. The average coefficient for the within-person effect of relationship status on psychological distress was significant and negative (b = −.11, SE = .04, z = −2.93, p = .003), indicating that LGB youth showed less psychological distress at time points when involved in a relationship than at time points when they were not (see Table 2, Model 1). The variance of this coefficient was significant (b = .18, SE = .03, z = 5.73, p <.001; not shown in Table), indicating that the association differed between participants and tests of moderation were possible.

Table 2.

Within-Person Prediction of Psychological Distress

| Within-Level Predictor | b | SE | z | p | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| Relationship Involvement | −.11 | .04 | −2.93 | .003 | .04 |

| Age | −.12 | .03 | −4.76 | < .001 | .05 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Relationship Involvement | −.06 | .07 | −.84 | .40 | .001 |

| Age | −.13 | .04 | −3.66 | < .001 | .01 |

| Relationship Inv.*Age | .02 | .07 | .30 | .76 | < .001 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age, gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity at the between-persons level.

Next, we examined whether the within-person association between relationship involvement and psychological distress changed across development. In this model (see Table 2, Model 2), a latent variable interaction was used to model the interaction between age and relationship involvement at Level 1, as recommended by Preacher, Zhang, and Zyphur (2016). Age, relationship involvement, and their interaction were included as within-person (i.e., Level 1) predictors of psychological distress. Results indicate that age did not moderate the association between relationship involvement and psychological distress.

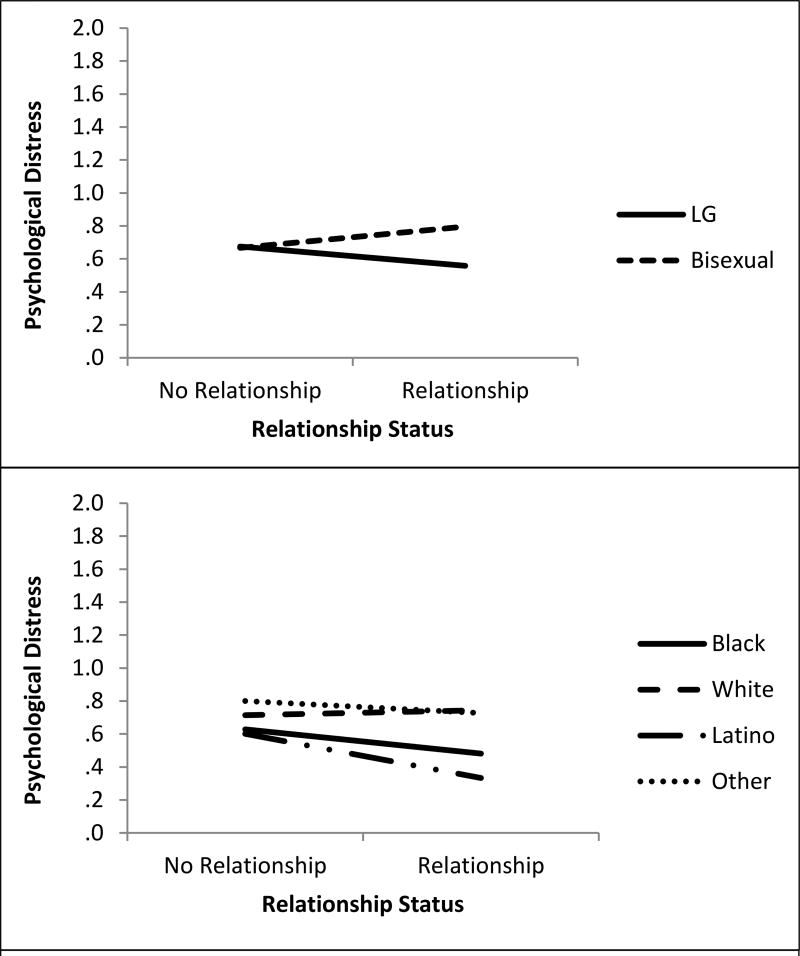

The subsequent three models tested whether the association between relationship involvement and psychological distress differed based on individuals’ gender, sexual identity, or race/ethnicity. Each moderator (i.e., gender, sexual identity, or race/ethnicity) was added as a Level 2 predictor of the within-person association between relationship involvement and psychological distress, in separate models. See Table 3 and Figure 1 for results. Gender was examined first. Given the small number of transgender individuals (n = 20), they were not included in these analyses. Gender did not predict the within-person association between relationship involvement and psychological distress, indicating that this association did not differ between cismen and ciswomen. In analyses examining sexual identity as a moderator, the small proportion of the sample who identified as unsure, questioning, or heterosexual (n = 24) were not included. Results indicated that sexual identity moderated the within-person association between relationship involvement and psychological distress. Simple slopes analyses indicated that relationship involvement was associated with lower psychological distress for lesbian/gay individuals (b = −.12, SE = .02, z = −4.89, p < .001), but higher psychological distress for bisexual individuals (b = .13, SE = .04, z = 3.45, p < .001).

Table 3.

Tests of Potential Moderators of the Within-Person Association Between Relationship Involvement and Psychological Distress

| Potential Moderator | b | SE | z | p | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −.09 | .06 | −1.39 | .17 | .001 |

| Sexual Identity | .25 | .04 | 5.45 | < .001 | .01 |

| Race/Ethnicity (vs. Black) | |||||

| White | .18 | .10 | 1.71 | .09 | .002 |

| Latino | −.12 | .18 | −.68 | .49 | < .001 |

| Other | .07 | .10 | .76 | .44 | < .001 |

Note. Reference groups cisgender female, lesbian/gay, and Black. Coefficients represent the association between the moderator and the random coefficient for relationship status predicting psychological distress, controlling for age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the between-persons level and age at the within-persons level.

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of the association between relationship status and psychological distress by sexual identity (top) and race/ethnicity (bottom).

Race/ethnicity was examined next. Black participants, the largest racial group (n = 139; 56%) served as the reference group. Results indicated that the association between relationship involvement and psychological distress for Black participants was marginally different than for White participants, but did not differ from the association for Latino participants or participants of other racial/ethnic identities. Simple slopes analyses revealed that being in a relationship predicted less psychological distress for Black participants (b = −.15, SE = .04, z = −3.43, p = .001), but was not associated with psychological distress for White participants (b = .03, SE = .09, z = .33, p = .74). The simple slopes for Latino and other race participants were negative and did not differ from the simple slope for Black participants, but were not statistically-significant, likely due to small ns within each group (for Latino participants [n = 30], b = −.27, SE = .17, z = −1.54, p = .12; for participants from other racial/ethnic groups [n = 44]; b = −.07, SE = .09, z = −.80, p = .42).

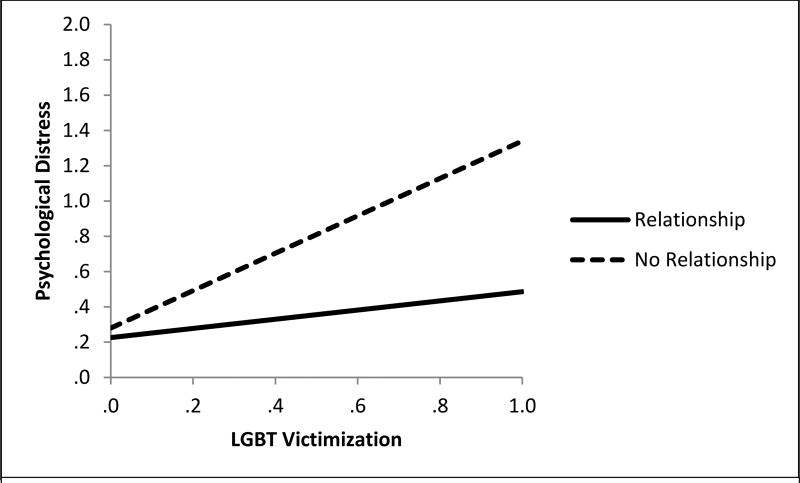

Tests of Stress Buffering Effects of Relationship Involvement on Psychological Distress

Next, we tested whether being in a relationship reduced the association between LGBT victimization experiences and psychological distress (i.e., stress-buffering effects of relationship involvement). LGBT victimization (grand-mean centered), relationship involvement, and their interaction were included as within-person (i.e., Level 1) predictors of psychological distress. Results (shown in Table 4) indicated that relationship involvement moderated the association between LGBT victimization and psychological distress. Simple slopes analyses (see Figure 2) indicated that level of victimization was positively associated with psychological distress for single participants (b =1.07, SE = .23, z = 4.63, p < .001), but not for those in relationships (b = .26, SE = .45, z =.57, p = .57).

Table 4.

Tests of the Stress Buffering Model: Within-Person Prediction of Psychological Distress

| Within-Level Predictor | b | SE | z | p | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship Involvement | −.08 | .04 | −1.88 | .06 | < .001 |

| Victimization | 1.11 | .28 | 4.63 | < .001 | .02 |

| Relationship Inv.*Victimization | −.81 | .42 | −1.93 | .05 | .01 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age, gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity at the between-persons level.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of the association between LGBT victimization and psychological distress by relationship status.

Finally, we examined whether the buffering effect of relationship involvement on the association of victimization and psychological distress was moderated by gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity, or age. For models testing gender, sexual identity, or race/ethnicity as moderators, we used a three-way interaction in which victimization and one moderator (relationship involvement) were at the within level and the second moderator (gender, sexual identity, or race/ethnicity) was at the between level. For the model examining whether the relationship buffering effect differed across development, the predictor and both moderators were at the within-persons level. None of the three-way interactions were significant (ps > .30), suggesting the buffering effect of relationship involvement on the association between victimization and psychological distress is similar across age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity.

Discussion

The current findings extend our understanding of how romantic relationship involvement influences the psychological health of young sexual minorities. In contrast to most previous research, which has focused on heterosexual adults or used cross-sectional designs, these longitudinal data from a diverse sample of LGBT youth allowed examination of how relationship involvement is associated with psychological distress within young sexual minority individuals over time. Overall, the findings provide novel evidence that sexual minority youth experience less psychological distress at times when they are involved in a romantic relationship than at times when they are not. Further, being in a romantic relationship buffered LGBT youth from the negative psychological effects of sexual orientation victimization. These findings build upon previous research indicating that gay and lesbian adults in romantic relationships report better psychological wellbeing than those who are single (e.g., Kornblith et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2013; Wayment & Peplau, 1995) to provide the strongest evidence to date that the “marriage benefit” to mental health does indeed extend to the non-marital romantic partnerships of young sexual minorities. Together with similar findings for heterosexual young adults (e.g., Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005; Simon & Barrett, 2010; Whitton et al., 2013), these findings suggest that committed partnerships other than marriage may be a protective factor for young people broadly.

In fact, echoing findings from adult heterosexual samples (Simon, 2002; Kamp Dush & Amato, 2005), the association between relationship involvement and psychological distress was consistent across gender, suggesting that being in a romantic relationship is equally beneficial to the psychological health of male and female cisgender sexual minorities. Perhaps most interestingly, the association between relationship involvement and psychological distress was also not moderated by age in our sample. This suggests that the observed psychological benefits of being in a romantic relationship for sexual minorities are consistent from middle adolescence into young adulthood (i.e., across ages 16–26), contrasting with the literature on heterosexual individuals, which generally suggests that the mental health benefits of relationship involvement observed among adults do not extend to adolescents. Rather, being in a relationship has been associated with higher levels of psychological distress in samples of heterosexual adolescents aged 10–18 years (e.g., Compian et al., 2004; Davila et al., 2004; Joyner & Udry, 2000; Quatman et al., 2001). It is possible that the lack of a moderating effect of age was related to the age of our sample (i.e., 16+ years) since the most robust evidence of negative psychological effects of heterosexual romantic involvement has been found in younger adolescents. That said, research on heterosexuals suggests negative effects of relationship involvement in samples of 18 year olds (Davila et al., 2004), who were well-represented in our sample. Therefore, it might also be that romantic involvement is not generally depressogenic for sexual minority teens in the way that it is for their heterosexual counterparts. Perhaps, because LGBT youth generally experience more stress and social isolation than heterosexual youth, the social support received from a romantic partner is more powerful in promoting psychological health. Consistent with this notion, the few other studies using samples of sexual minority adolescents have not found differences in psychological distress by relationship involvement (Baams et al., 2014; Bauermeister et al., 2010; Russell & Consolacion, 2003).

The within-person association between romantic involvement and psychological distress did, however, vary based on sexual identity and race/ethnicity. These findings indicate that relationship involvement may only be a protective factor for mental health among some, but not all, sexual minority youth. Most strikingly, whereas being in a romantic relationship predicted lower psychological distress for gay and lesbian youth, it predicted higher psychological distress for bisexuals. Together with evidence that bisexual adults in relationships are at greater risk of having an anxiety disorder than are single bisexuals (Feinstein et al., 2016), this finding suggests that romantic involvement may be a risk factor for psychological dysfunction among bisexual individuals. It is possible that bisexuals encounter unique stressors when engaged in a romantic relationship that are not experienced by sexual minorities attracted to only one gender (i.e., lesbian and gay youth). Specifically, as a result of society’s binary conceptualization of sexual orientation, bisexuals who become involved with a same-sex or different-sex partner may face heightened denial of their sexual identity by outsiders, along with pressure from their partner to identify in a way that matches the present gender-pairing (Dyar et al., 2014). These additional stressors may counter any psychological benefits of relationship involvement and even create more distress than typically experienced when single. Given mounting evidence that bisexual individuals experience more mental health difficulties than other sexual minorities (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, & McCabe, 2010), there is a critical need for future research to identify the mechanisms of risk.

The association between relationship involvement and psychological distress also differed by race/ethnicity: Current romantic involvement was associated with lower levels of psychological distress among Black participants, but not among those who identified as White. For Latino participants, this association was similar (actually slightly stronger in magnitude) to that observed among Black participants, although it was not statistically significant due to a small n and higher within-group variability. Although replication is needed before confident conclusions are drawn, it suggests that romantic involvement may serve as a protective factor for the mental health of young sexual minorities of color. Perhaps being in a relationship is particularly beneficial for Black (and possibly Latino) sexual minorities because a supportive romantic partner can offer emotional support to help cope with the compounded stressors they face due to their multiple minority statuses (e.g., Meyer et al., 2008; Szymanski & Meyer, 2008). Further, due to racism present within the LGBTQ community, homonegativity within racial/ethnic communities, and both racism and homonegativity within the mainstream community (e.g., Greene, 1996), sexual minorities of color may have fewer accepting social supports outside of their romantic relationships.

The lack of an association for White participants was somewhat surprising because the majority of research on sexual minority adults, which suggests relationship involvement is associated with less psychological distress, has been based on predominantly White samples. Although the small number of White participants (n = 35) raises concerns that we did not have sufficient power to detect an effect that was actually present in this group, the simple slope for White participants was very close to zero. This raises the possibility that, for White sexual minority youth, romantic involvement may not provide any mental health benefits. It also suggests that the discrepancy between our overall findings and other studies of adolescents, which have found no effect or a negative effect of romantic involvement on mental health, are due to differences in the racial makeup of the samples. That is, if the benefits of relationship involvement are present primarily for young people of color, convenience samples that are predominantly White may miss these effects. Study of racial differences in youth of all sexual orientations is needed.

The present findings also provide evidence that romantic involvement may protect young sexual minorities from the detrimental psychological effects of minority stressors, consistent with stress buffering theories (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Specifically, the association between victimization due to sexual orientation and psychological distress, present when participants were single, was not present when participants were romantically involved. Further, this buffering effect was not moderated by any demographic variables, suggesting that being in a relationship may buffer young sexual minorities of all ages, genders, sexual identities, and races from the negative effects of victimization. This finding has particular significance for efforts to promote the health of LGBT youth, who are insulted, threatened, or attacked due their sexual orientation at high frequencies (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2015). There is a clear need to identify factors that may protect sexual minority youth from the harm that such experiences inflict upon their psychological health (Mustanski, 2015). Existing evidence does not support general social support (received from all sources; e.g., Feinstein, Wadsworth, Davila, & Goldfried, 2014) or social support from family and friends (Graham & Barnow, 2013; Mustanski et al., 2011) as effective buffers against sexual minority stressors. In contrast, there may be something unique about the support from a romantic partner that can help reduce sexual minorities’ vulnerability to psychological distress in the face of victimization (Graham & Barnow, 2013).

Several study limitations should be noted. First, although the overall sample was sizeable for a study of sexual minority youth, numbers of specific demographic subgroups were small. There were too few transgender individuals to explore potential differences from cisgender individuals, and we did not capture non-binary gender identities. Future research should explore how relationship involvement is associated with wellbeing across multiple gender identities, particularly considering the increasing number of LGBT people who identify as non-binary or transgender (Richards et al., 2016). Similarly, because young people today identify with a wide variety of sexual identities, including pansexual, queer, and asexual, future research should use measures that capture identities other than gay/lesbian and bisexual. The number of participants who identified as White and Latino were relatively small (ns = 35 and 30, respectively), and other racial groups were too small to examine separately. Future research using large samples with more equal distribution across various demographic factors is needed. Second, because the tests for moderation of the stress buffering effect by demographic characteristics used three-way interactions, which have lower power than main effects (Heo & Leon, 2010), we may have missed true demographic differences in the stress buffering effect of relationship involvement. Third, this dataset did not include information on the gender of participants’ relationship partners, despite evidence that involvement in same-sex versus different-sex relationships may have different implications for psychological wellbeing among LGBT youth (Beaumeister et al., 2010; Russell & Consolacion, 2003). We also did not examine sexual activity with partners, though some research suggests that it is sex, not romantic involvement itself, that is associated with adolescent depression (Mendle et al., 2013). Finally, we did not assess sequencing effects; future work should explore whether being single has different effects on psychological wellbeing depending on past relationship involvement.

Despite these limitations, the current study furthers our understanding of the associations between romantic involvement and psychological health in sexual minority youth. The longitudinal data suggest that, overall, involvement in a romantic relationship may have both direct and stress-buffering effects on LGBT youth’s psychological wellbeing. Efforts to reduce the mental health disparities faced by young sexual minorities, therefore, might benefit from inclusion of strategies to promote involvement in healthy romantic relationships. Such strategies could include educating youth and their allies about how to form and maintain healthy romantic relationships. However, the present findings also suggest that the psychological benefits of relationship involvement may not be present for all individuals; only those who identified as gay or lesbian (vs bisexual) and as Black or Latino (vs. White) experienced improvements in psychological wellbeing when romantically partnered. Most notably, bisexual youth actually experienced heightened psychological distress when involved in a relationship. Consequently, theoretical models and intervention efforts must attend to individual differences among sexual minorities in how romantic involvement may affect psychological health.

GSS.

Marriage is a well-established protective factor for mental health among heterosexual adults. This study suggests that romantic involvement is also associated with psychological wellbeing among young sexual minorities, particularly those who are also ethnic minorities and those who identify as gay or lesbian.

Footnotes

Author Note: (redacting contact and funding information for blind review) Some of the hypotheses and results in the manuscript were presented in 2017 at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) and the 5th Annual National LGBTQ Health Conference.

Contributor Information

Sarah W. Whitton, University of Cincinnati

Christina Dyar, University of Cincinnati.

Michael E. Newcomb, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Brian Mustanski, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

References

- Ayala J, Coleman H. Predictors of depression among lesbian women. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2000;4:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Bos HM, Jonas KJ. How a romantic relationship can protect same-sex attracted youth and young adults from the impact of expected rejection. J Adolesc. 2014;37:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TG, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:1148–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hequembourg A. ‘Just a little hint’: bisexual-specific microaggressions and their connection to epistemic injustices. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2014;16:488–503. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.889754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, Fincham FD. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal relationships. 2010;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Moradi B. Perceived experiences of anti-bisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:451–468. doi: 10.1037/a0021116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and aging. 1992;7:331. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin. 1985;98:310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American psychologist. 2009;64:170. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compian L, Gowen LK, Hayward C. Peripubertal girls’ romantic and platonic involvement with boys: Associations with body image and depression symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:23047. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J. Depressive symptoms and adolescent romance: Theory, research, and implications. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Steinberg SJ, Kachadourian L, Cobb R, Fincham F. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of preoccupied relational style. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, London B. Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Child and society. 1950:53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Latack JA, Bhatia V, Davila J, Eaton NR. Romantic relationship involvement as a minority stress buffer in gay/lesbian versus bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2016;20:237–257. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2016.1147401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Wadsworth LP, Davila J, Goldfried MR. Do parental acceptance and family support moderate associations between dimensions of minority stress and depressive symptoms among lesbians and gay men? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2014;45:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Barnow ZB. Stress and social support in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples: direct effects and buffering models. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27:569–578. doi: 10.1037/a0033420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene B. Lesbian women of color: Triple jeopardy. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 1996;1:109–147. doi: 10.1300/J155v01n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo M, Leon AC. Sample Sizes Required to Detect Two-Way and Three-Way Interactions Involving Slope Differences in Mixed-Effects Linear Models. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2010;20:787–802. doi: 10.1080/10543401003618819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:54–74. doi: 10.1177/0886260508316477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annual review of sociology. 1988;14:293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for a Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB. Specifying the buffering hypothesis: Support, strain, and depression. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1992;55:363–378. doi: 10.2307/2786953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR. You don't bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush CM, Amato PR. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:607–627. doi: 10.1177/0265407505056438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:142–167. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith E, Green RJ, Casey S, Tiet Q. Marital status, social support, and depressive symptoms among lesbian and heterosexual women. J Lesbian Stud. 2016;20:157–173. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2015.1061882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb KA, Lee GR, DeMaris A. Union formation and depression: Selection and relationship effects. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:953–962. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Butterfield RM. Social Control in Marital Relationships: Effect of One's Partner on Health Behaviors1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2007;37:298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Reczek C, Brown D. Same-sex cohabitors and health the role of race-ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:25–45. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke O, Marsh HW, Robitzsch A, Trautwein U, Asparouhov T, Muthén B. The multilevel latent covariate model: a new, more reliable approach to group-level effects in contextual studies. Psychological methods. 2008;13:203. doi: 10.1037/a0012869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, Hemken D. Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. Int J Behav Dev. 2015;39:87–96. doi: 10.1177/0165025414552301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Ferrero J, Moore SR, Harden K. Depression and adolescent sexual activity in romantic and nonromantic relational contexts: A genetically-informative sibling comparison. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0029816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MJ. Psychosocial intimacy and identity: From early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20:346–374. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Future directions in research on sexual minority adolescent mental, behavioral, and sexual health. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:204–219. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.982756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Garofalo R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2011;23:204–225. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.561474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Mustanski B. Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a longitudinal multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:783–793. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetjen H, Rothblum ED. When lesbians aren't gay: Factors affecting depression among lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;39:49–73. doi: 10.1300/J082v39n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JJ, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Fincham FD. “Hooking up” among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of sexual behavior. 2010;39:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Starks TJ, DuBois S, Grov C, Golub SA. Alternatives to monogamy among gay male couples in a community survey: Implications for mental health and sexual risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ. Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological methods. 2016;21:189. doi: 10.1037/met0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatman T, Sampson K, Robinson C, Watson CM. Academic, motivational, and emotional correlates of adolescent dating. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 2001;127:211–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, Barker MJ, Nieder TO, T’Sjoen G. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry. 2016;28:95–102. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Tellegen A. Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child development. 2004;75:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Reconceptualizing marital status as a continuum of social attachment. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1995;57:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Consolacion TB. Adolescent Romance and emotional health in the United States: Beyond binaries. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:499–508. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW. Revisiting the Relationships among Gender, Marital Status, and Mental Health 1. American journal of sociology. 2002;107:1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TA, Bosker RJ. Modeled variance in two-level models. Sociological methods & research. 1994;22:342–363. [Google Scholar]

- Syrotuik J, D’Arcy C. Social support and mental health: Direct, protective and compensatory effects. Social Science and Medicine. 1984;18:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Meyer D. Racism and heterosexism as correlates of psychological distress in African American sexual minority women. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2008;2:94–108. doi: 10.1080/15538600802125423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Brown RL. A handbook for the study of mental health. 2. United States of America: Cambridge University Press; 2010. Social support and mental health; pp. 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of health and social behavior. 1987:306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanassche S, Swicegood G, Matthijs K. Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effects of marital status and children on wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;14:501–524. [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. 1. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wayment HA, Peplau LA. Social Support and Well-Being Among Lesbian and Heterosexual Women: A Structural Modeling Approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:1189–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Kuryluk AD. Associations between relationship quality and depressive symptoms in same-sex couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:571–576. doi: 10.1037/fam0000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Weitbrecht EM, Kuryluk AD, Bruner MR. Committed dating relationships and mental health among college students. Journal of American college health. 2013;61:176–183. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.773903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke C, Hill GJ. Does the “marriage benefit” extend to partners in gay and lesbian relationships? Evidence from a random sample of sexually active adults. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:259–289. [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Jacobsen P, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C, Derogatis L. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:241–246. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]